Abstract

SsoPox is a lactonase endowed with promiscuous phosphotriesterase activity isolated from Sulfolobus solfataricus that belongs to the Phosphotriesterase-Like Lactonase family. Because of its intrinsic thermal stability, SsoPox is seen as an appealing candidate as a bioscavenger for organophosphorus compounds. A comprehensive kinetic characterisation of SsoPox has been performed with various phosphotriesters (insecticides) and phosphodiesters (nerve agent analogues) as substrates. We show that SsoPox is active for a broad range of OPs and remains active under denaturing conditions. In addition, its OP hydrolase activity is highly stimulated by anionic detergent at ambient temperature and exhibits catalytic efficiencies as high as kcat/KM of 105 M−1s−1 against a nerve agent analogue. The structure of SsoPox bound to the phosphotriester fensulfothion reveals an unexpected and non-productive binding mode. This feature suggests that SsoPox's active site is sub-optimal for phosphotriester binding, which depends not only upon shape but also on localised charge of the ligand.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organophosphates (OPs) are well-known potently toxic compounds because they irreversibly inhibit acetylcholinesterase, a key enzyme of the central nervous system1. They have been extensively used since the end of World War II, primarily as agricultural insecticides2. Their toxic properties have also been exploited for the development of chemical warfare agents (such as sarin, soman and VX). Enzymes that are capable of degrading OPs are therefore attractive as potential anti-dotes because of their intrinsic potential in decontamination/detection systems for organophosphates-based pesticides and nerve agents3. Enzymatic detoxification of OPs has become the subject of numerous studies because current methods of removing them, such as bleach treatments and incineration, are slow, expensive and cause environmental concerns. For this application, OP hydrolases are appealing due to their broad substrate specificity and their high catalytic rate3.

Bacterial phosphotriesterases (PTEs) are members of the amidohydrolase superfamily4, enzymes catalysing the hydrolysis of a broad range of compounds with different chemical properties (phosphoesters, esters, amides, etc.). PTEs hydrolyse insecticide-derivatives such as paraoxon with diffusion limit like kinetic parameters5,6. Moreover, PTEs catalyse the hydrolysis of various nerve agents with high efficiency7. Because the widespread dissemination of these man-made chemicals began only in the 1950's, it has been postulated that the PTEs might have evolved specifically to hydrolyse insecticides over a relatively short period of time8.

A protein from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus, SsoPox, was cloned, characterised and related to the PTE family (and was accordingly named paraoxonase9). SsoPox indeed shares approximately 30% sequence identity with mesophilic PTEs, but hydrolyses paraoxon and other pesticides with a lower efficiency9. SsoPox is an extremely thermostable enzyme, with an evaluated Tm of 104°C and a denaturation half-life of 90 minutes at 100°C9. The thermostability of SsoPox was mainly attributed to a large hydrophobic dimer interface and an extensive salt bridge network10, two classical features of hyperthermostable proteins11. SsoPox is thus considered as an excellent starting point for biotechnological applications12 and directed evolution (which was briefly explored13). Isolated by virtue of its phosphotriesterase activity, biochemical and phylogenetic evidence later suggested that SsoPox belongs to another closely related protein family, the Phosphotriesterase-Like Lactonase (PLLs)14. The structure of SsoPox confirmed that it is a natural lactonase with a promiscuous phosphotriesterase activity15,16. In particular, the activity detected against N-acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs)14,17 may relate SsoPox and the PLLs to the AHL-based quorum sensing system18 and its inhibition by quorum quenching17,19. The crystal structures of SsoPox free and in complex with an AHL mimic have illustrated the molecular adaptation of a dedicated lactonase to an optimised phosphotriesterase within the last few decades15. It is noteworthy that similar adaptations from lactonases to phosphotriesterases have occurred in at least three different families20, including the PLLs and PTEs (TIM barrel fold), the lactonases with a metallo-β-lactamase fold and the paraoxonase family using directed evolution (β-propeller fold)21. However, despite several X-ray structures of representatives for each family, there is no case where structures of the same protein are available with a native substrate mimic and the promiscuous substrate mimic.

In this study, we undertook biochemical studies on SsoPox that further illustrate the potential of this enzyme as an OP biodecontaminant. We performed kinetic characterization of SsoPox with a broad range of organophosphorus compounds including nerve agent analogues, as well as in various detergents and denaturing agents. Furthermore, we discuss the non-productive mode of fensulfothion-binding in the structure and its implications for substrate recognition in SsoPox's active site.

Results

SsoPox OP hydrolase activity characterisation

Catalytic parameters of SsoPox with (ethyl-)paraoxon (Fig. 1I) were characterised at 70°C (kcat/KM = (1.22±0.21)×103 M−1s−1) ( Table I ). These results are in agreement with previous studies17 ( Table SI ). Kinetic assays were also performed at 25°C ( Table I ) and reveal, for the first time, that SsoPox is approximately 2.5 times less efficient at 25°C than at 70°C (kcat/KM = (5.19±1.31)×102 M−1s−1). SsoPox is thus the most efficient PLL against paraoxon at both 70°C and 25°C9,14,22,23,24 ( Table SI & SII ). These values, however, are very low compared to the best organophosphate degrading enzyme, PTE from Pseudomonas diminuta which exhibits second order rate constants for paraoxon near the diffusion limit (kcat/KM ~ 108 M−1s−1)25. This observation is in agreement with the nature of PLLs which exhibit a promiscuous phosphotriesterase activity, whereas PTEs are natural phosphotriesterases14,20.

Chemical structure of organophosphorus compounds used in this study.

Chemical structure of (ethyl-)paraoxon (I), methyl-paraoxon (II), (ethyl-)parathion (III), methyl-parathion (IV), fensulfothion (V), malathion (VI), CMP-coumarin (VII), IMP-coumarin (VIII) and PinP-coumarin (IX) generated using ChemDraw software. All these compounds are phosphotriesters with the exception of the last three compounds that are phosphodiesters.

Others OPs were also tested as substrates at 25°C ( Table I ), including the phosphotriesters methyl-paraoxon, (ethyl-)parathion, methyl-parathion, malathion and the phosphodiesters CMP-coumarin, IMP-coumarin and PinP-coumarin (cyclosarin, sarin and soman derivatives, respectively, in which the fluoro substituent of cyclosarin has been replaced by a cyanocoumarin group26; see Methods for more details)(Fig. 1VII, VIII & IX). These assays showed that SsoPox exhibits about 2.5 times higher catalytic efficiency toward methyl-paraoxon than against (ethyl-)paraoxon (kcat/KM = (1.27±0.70)×103 M−1s−1 and (5.19±1.31)×102 M−1s−1, respectively). This preference is mainly due to a tenfold lower KM for methyl-paraoxon than for paraoxon. In a similar fashion, SsoPox shows higher catalytic efficiency for methyl-parathion (kcat/KM = 9.09 ± 0.90 M−1s−1), compared with parathion for which no catalysis could be detected. This result suggests that the bulkiness of the substituent groups of certain phosphotriesters prevents a catalytically efficient binding. This feature was also previously observed for SsoPox and SacPox at 70°C22 and for DrOPH at 35°C24.

Although methyl-paraoxon and methyl-parathion differ by only one atom (the terminal oxygen of the phosphorous moiety is a sulphur atom in parathion (Fig. 1IV)), SsoPox hydrolyses methyl-paraoxon approximately 100 times more efficiently (kcat/KM = (1.27±0.70)×103 M−1s−1 and 9.09 ± 0.90 M−1s−1, respectively). The observed KM values actually suggest that the Michaelis complex formation is more favourable with methyl-parathion than with methyl-paraoxon (approximately ten fold). However, the kcat decreases approximately 1000 times with methyl-parathion compared to methyl-paraoxon, which may reveal a less productive binding of thiono-phosphotriesters compared to that of oxons. This phenomenon was named the thiono-effect and a similar tendency was previously observed in Agrobacterium radiobacter PTE with chlorpyrifos and chlorpyrifos oxon27. However, PTEs do not exhibit such a drastic difference regarding paraoxon which is only a slightly better substrate than parathion5,28.

Kinetic parameters were also recorded for the hydrolysis of another sulphur-containing organophosphate, the insecticide malathion (kcat/KM = 5.56 ± 1.26 M−1s−1). This substrate possesses an equivalent KM value for the enzyme as for methyl-parathion, but the turnover is slower. Finally, SsoPox does not exhibit any detectable activity against PinP-coumarin, but hydrolyses the nerve agent analogs CMP-coumarin and IMP-coumarin with moderate efficiencies (kcat/KM = (8.13±0.08)×103 M−1s−1 and (1.67±0.04)×103 M−1s−1, respectively). These values are consistent with those of P. diminuta PTE against sarin and soman (kcat/KM of (9 ± 3)×104 M−1s−1 and (2.6 ± 0.2)×103 M−1s−1,respectively)7, although the coumarin derivatives are more activated substrates.

Anionic detergents enhance paraoxon hydrolysis catalysed by SsoPox

SsoPox paraoxonase activity enhancement by SDS. Previous results have shown that SDS increases paraoxon hydrolysis by wt SsoPox13. In this study, we tested various concentrations of SDS (Fig. 2A); the highest effect occurs at 0.01% with a velocity enhancement of approximately 5.5 times. The catalytic parameters of SsoPox at 25°C were thus characterised in the presence of 0.01% of SDS ( Table I ) and highlight an approximately 12.5 times catalytic efficiency enhancement compared to that without detergent at 25°C (Fig. 2H).

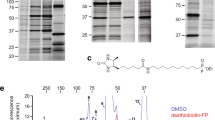

Enhancement of the paraoxonase activity of SsoPox by different chaotropic agents or detergents.

The relative velocity of SsoPox against 1 mM of paraoxon (A., C., D., E., F.) or 100 μM of paraoxon (B) in the presence of various concentrations of destabilising molecules is represented compared to activity without detergent (buffer taking value 1). (G) The highest effect of each compound (DOC, SDS, Tween 20, Urea, Guanidinium Chloride and DMSO) on velocity is represented and the concentrations are indicated. (H) The relative catalytic efficiency of SsoPox against paraoxon at various concentrations of SDS and DOC is represented relative to the catalytic efficiency without detergent (control). The backgrounds for the different reactions are presented in Table SVI.

Enhancement of SsoPox paraoxonase activity by DOC. Different DOC concentrations were used during the kinetic experiments (Fig. 2B). The greatest effect was obtained with 0.05% DOC (kcat/KM = (1.72±0.21)×104 M−1s−1) ( Table I ). With approximately 33 fold catalytic efficiency improvement (Fig. 2H), the observed effect with 0.05% DOC is more pronounced than that observed with SDS. These results indicate that despite having two very different chemical structures ( Fig. S1 ), the two anionic detergents SDS and DOC improve the kinetic parameters of SsoPox against paraoxon. Interestingly, this improvement might have different causes, because SDS produces an apparently equivalent effect on kcat and KM whereas DOC positively impacts KM but decreases kcat ( Table I ).

Effect of anionic detergents on nerve agent analogues hydrolysis. The ability of DOC and SDS to enhance the CMP-coumarin hydrolysis by SsoPox has been tested using 0.01% of each detergent ( Table I ). Catalytic parameters show that DOC and SDS allow catalytic efficiency enhancements of approximately 6 and 23 times, respectively, (DOC: kcat/KM = (4.63±1.16)×104 M−1s−1; SDS: kcat/KM = (1.9±0.1)×105 M−1s−1), which illustrates the potential of SsoPox for nerve agent decontamination.

SsoPox was characterised to be homodimeric in crystals15 and a rapid equilibrium between monomeric and dimeric forms was observed with size exclusion chromatography experiments9. A possible explanation for the observed paraoxon hydrolysis enhancement is a detergent-induced dissociation of the SsoPox homodimer that could influence the kinetic parameters of the enzyme. Another possibility is a conformational change of the enzyme induced by the detergents. These possibilities were investigated by size exclusion chromatography ( Fig. S2A ), DLS experiments ( Fig. S2B ) and tryptophan fluorescence ( Fig. S2C ), but these studies did not reveal any significant differences with or without SDS.

Effect of other denaturing agents on SsoPox paraoxonase activity

Other denaturing compounds (guanidinium chloride, urea, tween 20, DMSO; see methods for more details) were used and their effect on the paraoxonase activity was recorded. All of the tested compounds can improve the hydrolysis of paraoxon catalysed by SsoPox (Fig. 2), albeit with variable amplitudes. Interestingly, unlike the two anionic detergents tested in this study, tween 20 only induces a mild improvement (Fig. 2C). Chaotropic agents such as guanidinium chloride (Fig. 2D) or urea (Fig. 2E), as well as the organic solvent DMSO (Fig. 2F), show very little paraoxon hydrolysis enhancement. The highest enhancements are observed with the anionic detergents SDS and DOC (Fig. 2G).

Fensulfothion is an inhibitor for SsoPox

Fensulfothion is a substrate for the P. diminuta PTE5 but was previously mentioned as a potent inhibitor for SsoPox9. It thus constitutes a good candidate for structural studies, given the very high similarity between the chemical structures of fensulfothion and paraoxon (Fig. 1V & I). Preliminary experiments with SsoPox demonstrated that the KI of fensulfothion, given that this molecule is not water-soluble, is too high to be characterised in classical conditions (data not shown). However, the KI could be determined in 0.01% SDS (7.78 ± 1.23 mM) ( Fig. S3 ). This value is very similar to the KM values of the enzyme for paraoxon (24 mM without SDS; 4 mM with 0.01% SDS). Because of technical limitations, such as the very low solubility of fensulfothion in water, we were unable to determine experimentally the nature of the inhibition by kinetic experiments.

Unexpected binding mode of the fensulfothion

SsoPox is an enzyme that catalyses two different types of reaction: the hydrolysis of lactones, its preferred substrate and the hydrolysis of promiscuous substrates, the OPs. The mechanism by which the two different chemical reactions occur within the same active site is not known yet, but some evidence suggests that the promiscuity originates in lactonases from an overlap between the stabilisation of the transition state species of the native substrate and the binding of the promiscuous one20,29. To understand how phosphotriesters bind to the active site of SsoPox, we performed co-crystallisation experiments with various phosphotriesters. Attempts with triethylphosphate and diethyl (4-methylbenzyl) phosphonate failed (Elias et al., unpublished). A complexed SsoPox structure was obtained with the inhibitor fensulfothion at medium resolution (2.68 Å). Interestingly, the binding mode of fensulfothion to the SsoPox's active site is completely unexpected. Indeed, being (i) a very close mimic of paraoxon and (ii) a substrate for the P. diminuta PTE, fensulfothion's binding mode was expected to reveal the phosphotriester-binding mode of SsoPox. However, the structure reveals that the phosphorous moiety of fensulfothion does not bind to the bi-metallic centre, whereas the methyl sulfinyl group occupies the active site (Fig. 3A). This unexpected configuration is unambiguous from the electronic density map, despite the medium resolution of the structure (Fig. 3B). Indeed, the presence of two heavy groups on both sides of the molecule (sulfinyl group on one side, the phosphothio- moiety on the other) enables easy interpretation of the electronic density maps. It is noteworthy that putative nonproductive crystallographic complexes were also previously described with bound phosphotriesters to the P. diminuta PTE structure30.

Structural studies.

(A) Structural superposition between the apo structure of SsoPox (PDB ID: 2vc5; monomer A) (in light grey sticks) and the complexed structure of SsoPox with fensulfothion (monomer C; in blue sticks). The contacting monomers (forming the SsoPox homodimer) are shown in dark grey (apo structure) and cyan (fensulfothion-bound structure). The fensulfothion molecule is shown as green sticks and the two metal ions in the active site are represented by two spheres. (B) Fourier difference electronic density omit map for the bound fensulfothion. The Fobs-Fcalc electronic density map was calculated omitting the fensulfothion molecule from the model in all monomers. The electronic density map is shown as a blue mesh (contoured at 2.5σ) and as a black mesh (contoured at 3.5σ). (C) Ribbon representation of SsoPox homodimers from the apo structure (PDB ID: 2vc5; in red), the C10-homocysteine thiolactone (C10-HTL) bound structure (PDB ID: 2vc7; in yellow) and the fensulfothion-bound structure (in blue). The structures are superposed onto one monomer of the apo structure of SsoPox (right monomer). This enables the observation of the relative re-orientation of the second monomer in the other structures. (D) Close view on the binding of fensulfothion (green sticks; monomer C) in the active site of SsoPox (blue sticks). Metal cations and active site water molecules (in red) are shown as spheres. W2 corresponds to W362 (monomer A) in the deposited PDB coordinate file. Distances are indicated in Ångstrom.

The active site loop (loop 8) adopts a different conformation with fensulfothion binding, altering the dimer orientation

The fensulfothion-bound crystal structure of SsoPox reveals conformational changes within the active site, especially related to the loop 8 conformation. This active site loop has been described as a key feature for lactone binding, because it creates a hydrophobic channel that binds the aliphatic acyl chain of lactones and undergoes conformational changes upon the lactone binding15. The structural comparison of the fensulfothion-bound structure with the apo SsoPox structure (Fig. 3A) reveals that the whole loop 8 adopts an alternate conformation. Residues W263, T265 and A266 interact with fensulfothion and undergo significant conformational changes (up to 2.5 Å).

The conformational changes that occur in loop 8 upon fensulfothion binding also influence the conformation of residues from the other monomer, because loop 8 is also involved in the dimerization of SsoPox (Fig. 3A). Consequently, we observe a relative reorientation of both monomers closer to each other, compared to the apo structure (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, the loop 8 conformation observed in the fensulfothion-bound structure is similar to the one observed in the lactone-bound structure. This is further illustrated by the similar dimer orientations of both bound structures compared to the apo structure (Fig. 3C).

Active site configuration

The sulfinyl group of fensulfothion binds to the bi-metallic active site and more precisely to the more buried metal (2.7 Å) (iron cation, α-metal) (Fig. 3D). The free doublet of electrons of the tetrahedral sulphur atom interacts (2.9 Å) with a water molecule (W2) bound to the more exposed metal (2.1 Å) (cobalt cation, β-metal). This water molecule also makes a hydrogen bond with the Y97 hydroxyl group (3.1 Å), a key residue for lactone binding15 that is conserved amongst all PLLs and known lactonases from the metallo-β-lactamase superfamily31. The rest of the fensulfothion molecule is bound in the hydrophobic channel of SsoPox, formed by loop 8.

Discussion

SsoPox, an appealing candidate for OPs biodecontamination, is a native lactonase with promiscuous phosphotriesterase activity that belongs to the PLL family14. Our kinetic characterisation experiments highlight the fact that SsoPox exhibits by far the highest paraoxonase activity amongst PLLs at both 70°C and 25°C9,14,22,23,24. Moreover, we provide kinetic characterisations for various organophosphorus compounds, including methyl-paraoxon, methyl-parathion, malathion, IMP-coumarin and CMP-coumarin. Interestingly, SsoPox exhibits very low catalytic efficiency towards P = S containing organophosphates (e.g., the insecticides parathion, methyl-parathion and malathion). Between P = S and corresponding P = O substrates (e.g., methyl-parathion and methyl-paraoxon), the kcat value differs by 3 orders of magnitude. PTEs, albeit preferring paraoxon to parathion as a substrate, do not exhibit this marked thiono-effect5,28, although some thiono-effect has been observed for ArPTE with chlorpyrifos and its oxon derivative27. PTEs constitute a protein family that is believed to have evolved in the last few decades to specifically hydrolyse man-made insecticides2. They have possibly emerged from native lactonases such as PLLs14 and thus may have evolved to suppress this thiono-effect for certain insecticides. Recently, a study succeeded in reconstructing a PLL-like lactonase from the pdPTE illustrating this potent evolutionary history32.

The ability of SsoPox to hydrolyse insecticides as well as nerve agent analogues such as CMP-coumarin and IMP-coumarin strengthens the potential of this enzyme in biodecontamination. Moreover, we show an increase of the catalytic efficiency with the anionic detergents SDS and DOC, whereas very little improvement was observed with Tween 20, various denaturing agents (urea and guanidinium chloride) and DMSO. The highest paraoxon hydrolysis rate was measured at 25°C with 0.05% DOC (kcat/KM = (1.72±0.21)×104 M−1s−1). SDS and DOC yield similar hydrolysis rate enhancements with CMP-coumarin as a substrate, suggesting that it may be possible to improve the OP hydrolase activity of SsoPox. The improvement observed with detergents on the room temperature activity of a hyperthermostable enzyme is a common feature11 that serves as evidence that hyperthermostable enzymes are too rigid at room temperature to be highly active11. However, in the case of SsoPox, the observed paraoxonase catalytic efficiency increase with temperature (2.5 fold improvement between 25°C and 70°C) and with detergents (33 fold with 0.05% DOC) vary considerably in amplitude, suggesting that detergents may have actions other than mimicking the conformational flexibility provided by the thermal energy. Our investigation of the possible modulation of SsoPox oligomeric state or protein conformation in the presence of SDS did not show any significant changes.

Moreover, we solved the structure of SsoPox in complex with a phosphotriester, fensulfothion. This structure reveals an unexpected binding mode. Fensulfothion binds to the bi-metallic active site by its sulfinyl group and not by the phosphorous moiety. This unexpected binding most likely explains why fensulfothion is an inhibitor, whereas closely related compounds such as methyl-parathion or paraoxon (differing mainly by having a nitro group instead of the methyl sulfinyl group of fensulfothion) are substrates for SsoPox. In addition, this structure also exemplifies the fact that blind enzymology can lead to misinterpretations in such cases. It also constitutes an interesting case of promiscuous binding to the SsoPox active site that could result in promiscuous chemistry if one substituent of the sulfinyl group is a good leaving group. This unproductive binding also reveals that SsoPox's active site hardly promotes productive binding of phosphotriesters. This feature could be partially explained by a smaller sub-site than PTEs, as previously noted15. Indeed, residues such as W263, Y97 and R223, which are key residues for the lactonase activity15, possibly trade off with the promiscuous activity and may therefore represent interesting mutational targets. This possible steric hindrance is consistent with the poor KM values of SsoPox for phosphotriesters (24 mM for paraoxon) and may also explain why methyl-paraoxon is a better substrate than ethyl-paraoxon, with a tenfold better KM.

Furthermore, the binding mode of the inhibitor fensulfothion is interesting because of the close chemical similarity between this molecule and the substrates paraoxon and parathion. Indeed, fensulfothion is less polarised than these two compounds, including at the phosphorous centre. Fensulfothion therefore has a higher propensity to bind according to its shape, yielding to non-productive orientations as has been previously proposed for thiono phosphotriesters compared to oxono which is more polarised27. The lower observed KM for parathion compared to that of paraoxon may also reflect a high affinity for sulphur atoms of the bi-metallic active site that could yield to non-productive binding modes.

Methods

Production-purification of SsoPox

The gene encoding for SsoPox was optimised for E. coli expression, synthetised by GeneArt (Germany) and subsequently cloned into the pET22b plasmid using NcoI and HindIII as restriction enzymes. Protein production was performed in E. coli BL21(DE3)-pGro7/GroEL strain cells (TaKaRa) in 8 litres of ZYP medium33 (100 μg/ml ampicillin, 34 μg/ml chloramphenicol) inoculated by an over-night pre-culture at a 1/20 ratio. Cultures grew at 37°C to reach OD600nm = 1.5. The induction of the protein was made by starting the consumption of the lactose in ZYP medium with an addition of 0.2 mM CoCl2 and a temperature transition to 25°C for 20 hours. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (3000 g, 4°C, 10 min), re-suspended in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, CoCl2 0.2 mM, 0.25 mg/ml lysozyme, 0.1 mM PMSF, 10 μg/ml DNAseI and 20 mM MgSO4) and stored at −80°C. Suspended frozen cells were thawed and disrupted by three steps of 30 seconds of sonication (Branson Sonifier 450; 80% intensity and microtip limit of 8). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (12000 g, 4°C, 30 min). As SsoPox is hyperthermostable9, host proteins were precipitated by incubation for 30 minutes at 70°C and harvested by centrifugation (12000 g, 4°C, 30 min). A second step of heating at 85°C for 15 minutes and centrifugation was performed to precipitate more host proteins. Thermoresistant proteins from E. coli were eliminated by performing ammonium sulphate precipitation (326 g/L). SsoPox was concentrated by ammonium sulphate precipitation (476 g/L) and suspended in buffer 50 mM HEPES pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM CoCl2. Remaining ammonium sulphate was removed by dialysis against the same buffer and the protein sample was then concentrated for separation on exclusion size chromatography (S75-16-60, GE Healthcare) to obtain pure protein.

Oligomerisation state-interaction analysis

Size exclusion chromatography: Experiments were performed in buffer 50 mM HEPES pH 8, 150 mM NaCl and 0.2 mM CoCl2 at room temperature with approximately 5 mg of purified protein using a GE Healthcare S75-16-60 column connected to an ÄKTA-FPLC UPC-900 apparatus and monitored by UNICORN 4.11 software. Experiments were performed in the presence of 0%, 0.1% and 0.01% (w/v) of SDS. The column was previously calibrated with standard proteins (Gel filtration calibration kit, GE Healthcare) of known mass. The resulting elution profile was used as standard to evaluate the molecular weight of species observed during the experiments.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS): Experiments were performed at room temperature using a zetasizer nano series apparatus (Malvern, UK) and the Zetasizer software. A total of 30 μL of purified SsoPox (4 mg/mL) was used in activity buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM CoCl2; pH adjusted with NaOH at 25°C) and different amounts of SDS (0%, 0.1% and 0.01%; w/v) were used to measure the hydrodynamic radius of particles in the protein solution at 633 nm.

Fluorescence experiments: Experiments were performed in activity buffer with the addition of 0%, 0.1% or 0.01% (w/v) SDS using a Varian Cary Eclipse apparatus monitored by the Cary Eclipse software. SsoPox protein (0.2 mg/mL) was excited at 280 nm (maximum excitation wavelength of tryptophan) and the emitted fluorescence was measured between wavelengths of 300 to 500 nm.

Kinetic assays

The time course of paraoxon hydrolysis by SsoPox at 70°C was monitored by following the production of p-nitrophenolate at 405 nm (ε = 17000 M−1cm−1) in a 1-cm path length cell with a Cary WinUV spectrophotometer (Varian, Australia) using the Cary WinUV software. Standard assays (500 μL) were performed in buffer 50 mM CHES pH 9, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM CoCl2, 6% (v/v) EtOH, with pH adjusted with NaOH at 70°C and using 5 μL of SsoPox (1.5 mg/mL) for each experiment. Catalytic parameters were evaluated using a substrate (paraoxon) concentration range from 0 to 6 mM. The initial velocities at each substrate concentration were calculated using Excel software (Microsoft). The background rates of paraoxon hydrolysis have been subtracted from the kinetic experiments ( Table SIII ) at each substrate concentration. The catalytic parameters were obtained by fitting velocities versus substrate concentration to the Michaelis-Menten (MM) equation using Graph-Pad Prism 5 software.

At 25°C, the paraoxonase, methyl-paraoxonase, parathionase and methyl-parathionase hydrolysis activity was followed at 405 nm (ε = 17000 M−1cm−1) with a microplate reader (Synergy HT) and Gen5.1 software in a 6.2 mm path length cell for 200 μL reactions in a 96-well plate. Paraoxonase activity was followed over the concentration range 0–18 mM, methyl-paraoxonase and methyl-parathionase activity have been followed over the concentration range 0–1 mM. Paraoxonase activity assays were also performed using 0.01% and 0.1% (w/v) SDS [sodium dodecyl sulphate (Sigma-Aldrich, France)( Fig. S1A )] and 0.1%, 0.05% and 0.01% (w/v) DOC [sodium deoxycholate (Sigma-Aldrich, France)( Fig. S1B )] over a range of paraoxon concentrations between 0 and 2 mM. Standard assays were performed in activity buffer. The substrate solvent final concentration (ethanol) is below 1% (v/v). Malathionase activity was performed in activity buffer supplemented with DTNB 2 mM to follow the malathion hydrolysis at 412 nm (ε = 13400 M−1cm−1) over concentrations ranging between 0 and 2 mM. The substrate solvent final concentration (DMSO) was 1% (v/v)). Time course hydrolysis of CMP-coumarin (methylphosphonic acid 3-cyano-4-methyl-2-oxo-2H-coumarin-7-yl ester cyclohexyl ester), IMP-coumarin (methylphosphonic acid 3-cyano-4-methyl-2-oxo-2H-coumarin-7-yl ester isopropyl ester) and PinP-courmarin (methylphosphonic acid 3-cyano-4-methyl-2-oxo-2H-coumarin-7-yl ester pinacolyl ester)26 were evaluated by following the release of cyanocoumarin at 412 nm (ε = 37000 M−1cm−1) in the activity buffer. Experiments of CMP-coumarin hydrolysis in the presence of 0.01% SDS and DOC were performed in the same conditions as previously explained. Catalytic parameters were evaluated over the substrate concentration range 0–750 μM. All kinetic experiments were performed in triplicate.

The initial velocities of these experiments were calculated using Gen5.1 software, the backgrounds of substrate hydrolysis subtracted ( Table SIII ) and catalytic parameters were obtained by fitting the data to the MM equation using Graph-Pad Prism 5 software.

Detergent assays

Simple kinetic experiments were performed in the presence of various detergents: SDS (w/v) (1%, 0.5%, 0.1%, 0.05%, 0.025%, 0.01% and 0.001%), tween 20 (v/v) (1%, 0.1% and 0.01%); denaturing agents such as guanidinium chloride (800 mM, 80 mM, 8 mM, 800 μM, 80 μM and 8 μM), urea (800 mM, 80 mM, 8 mM, 800 μM, 80 μM) and the solvent DMSO (v/v) (10% and 1%) and buffer 50 mM CHES pH 9, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM CoCl2, 6% (v/v) EtOH in the presence of 1 mM of paraoxon using 5 μL of SsoPox (3.5 mg/mL or 0.35 mg/mL when the enhancement effect of the paraoxonase activity was too high). At 25°C, the paraoxonase activity was followed at 430 nm (ε = 8970 M−1cm−1) with a microplate reader (Tecan) and Magellan software in a 6.2 mm path length cell for 200 μL reactions in a 96-well plate. Kinetic experiments in the presence of DOC were performed as previously described except that kinetics were performed with 1 μL of SsoPox (0.3 mg/mL), 100 μM of paraoxon and detergent concentrations of 0.001%, 0.005%, 0.01%, 0.025%, 0.05%, 0.1%, 0.25% and 0.5% (w/v). At 25°C, the paraoxonase activity was followed at 405 nm (ε = 17000 M−1cm−1) in activity buffer with a microplate reader (Synergy HT) and Gen5.1 software in a 6.2 mm path length cell for 200 μL reaction in 96-well plate. The average velocities and their respective errors were obtained from duplicate or triplicate experiments and the background rates of substrate hydrolysis (Table SIV) were subtracted from the recorded velocities.

Inhibition assay

The inhibition of the enzyme by fensulfothion was evaluated by performing kinetic assays against paraoxon (concentration range 0–300 μM) and by using different fensulfothion concentrations in buffer 50 mM CHES pH 9, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM CoCl2, 6% (v/v) EtOH with 0.01% (w/v) of SDS. Because of the low solubility of fensulfothion in water, it was dissolved in 100% acetonitrile and the kinetics were measured at final concentration of 10% (v/v) of acetonitrile. Experiments were performed with concentrations of 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 mM to evaluate the KI of fensulfothion.

Because of the low solubility of the substrate and the inhibitor, the velocities at high substrate concentration cannot be reached. Catalytic parameters (kcat; KM) cannot be determined directly. However, by fitting to linear regression the linear part of the MM plot (Graph-Pad Prism 5 software), the catalytic efficiencies (kcat/KM) have been determined. A Dixon plot cannot be made to determine the inhibition constant (KI); however, as previously performed34, the representation of the inverse of the catalytic efficiency at each fensulfothion concentration allows the fit of a linear regression where inhibition constant corresponds to the x-intercept (-KI).

Crystallisation

For the crystallisation studies presented herein, recombinant SsoPox was used. The enzyme was concentrated at 6 mg/mL. Co-crystallisation assays with fensulfothion were performed by adding 1 μL of a 100 mM fensulfothion solution (1:1 ratio in acetonitrile) in 30 μL of the protein solution (approximately 3.2 mM final). Crystallisation was performed using the hanging drop vapour diffusion method. Equal volumes (0.5–1 μL) of protein and reservoir solutions were mixed and the resulting drops were equilibrated against an 800 μL reservoir solution containing 23–25% (w/v) PEG 8000 and 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8). Thin crystals appeared after one week at 277 K.

Data collection and structure determination

Crystals were first transferred to a cryoprotectant solution composed of the reservoir solution and 25% (v/v) glycerol containing a 1/30 (v/v) ratio of a 100 mM fensulfothion solution. Crystals were then flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. X-ray diffraction data were collected at 100 K using synchrotron radiation at the ID23-1 beam line (ESRF, Grenoble, France) with a ADSC Q315r detector. A data set was recorded at 2.68 Å resolution ( Table II , Fig. S4 ). X-ray diffraction data were integrated, scaled and merged with the XDS program35 and the CCP4 program suite36. The phases were obtained using the native structure of SsoPox (PDB ID: 2vc5), performing a molecular replacement with MOLREP37. The model was built with Coot38 and refined using REFMAC39. The anisotropic displacement parameters were refined via four groups of translation-liberation-screw (TLS) parameterisation identified by REFMAC40. The final stereochemistry was checked using the MOL-PROBITY program41. Structure illustrations were performed using PyMol42. The coordinate file and the structure factors file of the fensulfothion bound SsoPox structure have been deposited to the Protein Data Bank under the accession number 3uf9.

References

Singh, B. K. Organophosphorus-degrading bacteria: ecology and industrial applications. Nat Rev Microbiol 7 (2), 156–64 (2009).

Raushel, F. M. Bacterial detoxification of organophosphate nerve agents. Current opinion in microbiology 5(3), 288–95 (2002).

LeJeune, K. E., Wild, J. R. & Russell, A. J. Nerve agents degraded by enzymatic foams. Nature 395 (6697), 27–8 (1998).

Seibert, C. M. & Raushel, F. M. Structural and catalytic diversity within the amidohydrolase superfamily. Biochemistry 44 (17), 6383–91 (2005).

Dumas, D. P., Caldwell, S. R., Wild, J. R. & Raushel, F. M. Purification and properties of the phosphotriesterase from Pseudomonas diminuta. J Biol Chem 264 (33), 19659–65 (1989).

Raushel, F. M. Chemical biology: Catalytic detoxification. Nature 469 (7330), 310–1 (2011).

Tsai, P. C. et al. Stereoselective hydrolysis of organophosphate nerve agents by the bacterial phosphotriesterase. Biochemistry 49 (37), 7978–87 (2010).

Ghanem, E. & Raushel, F. M. Detoxification of organophosphate nerve agents by bacterial phosphotriesterase. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 207 (2 Suppl), 459–70 (2005).

Merone, L., Mandrich, L., Rossi, M. & Manco, G. A thermostable phosphotriesterase from the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus: cloning, overexpression and properties. Extremophiles 9 (4), 297–305 (2005).

Del Vecchio, P. et al. Structural determinants of the high thermal stability of SsoPox from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. Extremophiles 13 (3), 461–70 (2009).

Vieille, C. & Zeikus, G. J. Hyperthermophilic enzymes: sources, uses and molecular mechanisms for thermostability. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 65 (1), 1–43 (2001).

Demirjian, D. C., Moris-Varas, F. & Cassidy, C. S. Enzymes from extremophiles. Current opinion in chemical biology 5 (2), 144–51 (2001).

Merone, L. et al. Improving the promiscuous nerve agent hydrolase activity of a thermostable archaeal lactonase. Bioresour Technol 101 (23), 9204–12 (2010).

Afriat, L., Roodveldt, C., Manco, G. & Tawfik, D. S. The latent promiscuity of newly identified microbial lactonases is linked to a recently diverged phosphotriesterase. Biochemistry 45 (46), 13677–86 (2006).

Elias, M. et al. Structural basis for natural lactonase and promiscuous phosphotriesterase activities. Journal of molecular biology 379 (5), 1017–28 (2008).

Elias, M. et al. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of the hyperthermophilic Sulfolobus solfataricus phosphotriesterase. Acta crystallographica 63 (Pt 7), 553–5 (2007).

Ng, F. S., Wright, D. M. & Seah, S. Y. Characterization of a phosphotriesterase-like lactonase from Sulfolobus solfataricus and its immobilization for quorum quenching. Appl Environ Microbiol (2010).

Popat, R., Crusz, S. A. & Diggle, S. P. The social behaviours of bacterial pathogens. Br Med Bull 87, 63–75 (2008).

Dong, Y. H. et al. Quenching quorum-sensing-dependent bacterial infection by an N-acyl homoserine lactonase. Nature 411 (6839), 813–7 (2001).

Elias, M. & Tawfik, D. S. Divergence and Convergence in Enzyme Evolution: Parallel Evolution of Paraoxonases from Quorum-quenching Lactonases. The Journal of biological chemistry 287 (1), 11–20 (2012).

Gupta, R. D. et al. Directed evolution of hydrolases for prevention of G-type nerve agent intoxication. Nat Chem Biol 7 (2), 120–5 (2011).

Porzio, E., Merone, L., Mandrich, L., Rossi, M. & Manco, G. A new phosphotriesterase from Sulfolobus acidocaldarius and its comparison with the homologue from Sulfolobus solfataricus. Biochimie 89 (5), 625–36 (2007).

Hawwa, R., Aikens, J., Turner, R. J., Santarsiero, B. D. & Mesecar, A. D. Structural basis for thermostability revealed through the identification and characterization of a highly thermostable phosphotriesterase-like lactonase from Geobacillus stearothermophilus. Arch Biochem Biophys 488 (2), 109–20 (2009).

Hawwa, R., Larsen, S. D., Ratia, K. & Mesecar, A. D. Structure-based and random mutagenesis approaches increase the organophosphate-degrading activity of a phosphotriesterase homologue from Deinococcus radiodurans. Journal of molecular biology 393 (1), 36–57 (2009).

Omburo, G. A., Kuo, J. M., Mullins, L. S. & Raushel, F. M. Characterization of the zinc binding site of bacterial phosphotriesterase. The Journal of biological chemistry 267 (19), 13278–83 (1992).

Ashani, Y. et al. Stereo-specific synthesis of analogs of nerve agents and their utilization for selection and characterization of paraoxonase (PON1) catalytic scavengers. Chemico-biological interactions 187 (1–3), 362–9 (2010).

Jackson, C. J., Liu, J. W., Coote, M. L. & Ollis, D. L. The effects of substrate orientation on the mechanism of a phosphotriesterase. Org Biomol Chem 3 (24), 4343–50 (2005).

Jackson, C. J. et al. Anomalous scattering analysis of Agrobacterium radiobacter phosphotriesterase: the prominent role of iron in the heterobinuclear active site. The Biochemical journal 397 (3), 501–8 (2006).

Ben-David, M. et al. Catalytic versatility and backups in enzyme active sites: the case of serum paraoxonase 1. Journal of molecular biology 418 (3–4), 181–96 (2012).

Benning, M. M., Hong, S. B., Raushel, F. M. & Holden, H. M. The binding of substrate analogs to phosphotriesterase. The Journal of biological chemistry 275 (39), 30556–60 (2000).

Momb, J. et al. Mechanism of the quorum-quenching lactonase (AiiA) from Bacillus thuringiensis. 2. Substrate modeling and active site mutations. Biochemistry 47 (29), 7715–25 (2008).

Afriat-Jurnou, L., Jackson, C. J. & Tawfik, D. S. Reconstructing a missing link in the evolution of a recently diverged phosphotriesterase by active-site loop remodeling. Biochemistry (2012).

Studier, F. W. Protein production by auto-induction in high density shaking cultures. Protein Expr Purif 41 (1), 207–34 (2005).

Walsh, H. A., O'Shea, K. C. & Botting, N. P. Comparative inhibition by substrate analogues 3-methoxy- and 3-hydroxydesaminokynurenine and an improved 3 step purification of recombinant human kynureninase. BMC Biochem 4, 13 (2003).

Kabsch, W. Automatic processing of rotation diffraction data from crystals of initially unknown symmetry land cell constants. Journal of Applied Crystalography 26, 795–800 (1993).

Collaborative Computational Project Number 4, The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta crystallographica 50, 760–3 (1994).

Vagin, A. & Teplyakov, A. An approach to multi-copy search in molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 56 (Pt 12), 1622–4 (2000).

Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60 (Pt 12 Pt 1), 2126–32 (2004).

Murshudov, G. N., Vagin, A. A. & Dodson, E. J. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 53 (Pt 3), 240–55 (1997).

Lamzin, V. S. & Wilson, K. S. Automated refinement of protein models. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography 49 (Pt 1), 129–47 (1993).

Chen, V. B. et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography 66 (Pt1), 12–21 (2010).

DeLano, W. L. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA, USA (2002).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Moshe Goldsmith for the kind gift of CMP-coumarin, IMP-coumarin and PinP-coumarin. We thank Professor Dan Tawfik for constructive discussions on the project and for hosting J.H. in its laboratory. We thank the AFMB laboratory (Marseille, France) for the access to protein production and crystallisation platforms. This work was granted by DGA, France (REI. 2009 34 0045). J.H. and G.G. are PhD students granted by DGA. M.E. is a fellow supported by the IEF Marie Curie program (grant No. 252836).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JH, GG and ME designed the experiments. JH, GG and ME performed the experiments. JH, GG, ME and EC analysed the results. JH, ME and EC wrote the paper. All the authors offer a critical review of the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

SUPPLEMENTARY INFO

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareALike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Hiblot, J., Gotthard, G., Chabriere, E. et al. Characterisation of the organophosphate hydrolase catalytic activity of SsoPox. Sci Rep 2, 779 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00779

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00779

This article is cited by

-

Disrupting quorum sensing alters social interactions in Chromobacterium violaceum

npj Biofilms and Microbiomes (2021)

-

Organophosphorus poisoning in animals and enzymatic antidotes

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2021)

-

Enzymatic decontamination of paraoxon-ethyl limits long-term effects in planarians

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

The neuroprotective effects of stimulation of NMDA receptors against POX-induced neurotoxicity in hippocampal cultured neurons; a morphometric study

Molecular & Cellular Toxicology (2020)

-

In vivo immobilization of an organophosphorus hydrolyzing enzyme on bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoate nano-granules

Microbial Cell Factories (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.