Abstract

Study design: Development of Tetraplegia Hand Activity Questionnaire (THAQ).

Setting: Patients and spinal cord injury (SCI) professionals from five rehabilitation centres in the Netherlands and Belgium.

Objective: To construct a disease-specific questionnaire to evaluate interventions to the arm–hand of tetraplegics in terms of gained and lost activities relevant to the patient.

Methods: All arm–hand function-related activities were inventoried by examining existing scales and interviewing spinal cord injury patients and professionals in the field. Subsequently, item reduction was achieved; first, in the technical construction by incorporating all activities in an item list, then reducing the list by selecting the items most likely to be sensitive to change after surgical or functional electro stimulation interventions on the arm–hand as judged by an expert panel, using a Delphi method.

Results: The arm–hand-related activity inventory comprised 652 activities. The technical construction of the items and the Delphi procedure resulted in a questionnaire with 153 items. The experts considered many of the ‘new’ activities more relevant for the evaluation of hand function interventions than those found in scales studied in the literature. This is reflected in a relatively large proportion of new activities (69%) for the item list of the THAQ, and even more in the domains work/admin/telecom (88%) and leisure (100%).

Conclusion: The questionnaire constructed to assess hand function-related activities contains relevant activities to evaluate arm–hand function-related interventions for tetraplegic SCI patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Loss of hand function is one of the most important disabilities for patients with a cervical spinal cord injury (SCI).1,2,3,4 Impaired motor and sensory functions in arms and hands result in a loss of joint mobility, grip strength, coordination of motion, proprioception and protective sensitivity.5,6,7,8 In addition, muscle spasm may occur.9,10 Owing to these motor impairments, these patients use grips other than those with normal hand function.2,3,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19 Many interventions, such as orthoses, tendon transfers, functional electro stimulation (FES) and the creation of a functional hand with a tenodesis, have been developed to modify or strengthen the grip of tetraplegic patients.2,20,21,22,23,24,25,26, 27,28,29,30,31,32, 33,34,35,36,37, 38,39,40

Evaluation of the outcome of treatment is important to allow an evidence-based decision on appropriate treatment policies and to judge the effort and costs involved. The results of these interventions can be described using the first two levels of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, (ICF),41 that is, the body function and structures, and activity level (Figure 1).

In rehabilitation medicine, treatment ultimately focuses on a patient's functional abilities and aims at restoring the patient's autonomous functioning.2,17,32,42,43,44 Therefore, we are interested in a rehabilitation outcome measure that also indicates the effectiveness of treatment in terms of gained and lost activities important in the daily life of the patient.

Many intervention studies use the outcome at the level of body functions, for example, grip strength and range of motion.15,28,33,34,45,46,47 However, measurements on the body function level do not allow a direct translation to the activity level.

Other SCI intervention studies introduced dexterity tests to indicate the limitations at the activity level. Examples are the Jebsen,48 Sollerman,49 and the grasp release test.50 These dexterity tests are capacity based. Although they do indicate the changes in impairments and in the patient's range of activities, they lack sufficient insight into two important issues. Firstly, what the patient can do does not always indicate what the patient actually will do in daily life. In particular, the self-care skills achieved in therapy are often not utilised at home due to the help of others.51,52,53 Secondly, dexterity tests do not reveal the subtle and important changes in the activity pattern in the daily life of the patients.

To assess the actual performed activities in daily life, a scale or a questionnaire are suitable and frequently used tools. The quadriplegia index of function has been specifically developed to document functional gains as a result of treatment in tetraplegic SCI.54 The feeding, grooming and bathing categories have good correlations with the level of injury documented in the ASIA upper extremity motor score, although ceiling effects have been reported.55,56,57,58 The QIF seems more appropriate to assess the overall rehabilitation treatment of tetraplegics rather than specific hand function interventions. The spinal cord independence measure (SCIM) is another disease-specific activity scale in which the score focuses on poor sphincter control and mobility.59,60 The SCIM is most meaningful in paraplegic patients, for tetraplegic patients, the scoring is poor on self-care, urinary management and car transfers.61 In addition, leisure- and work-related activities are not covered. Similar to the QIF, the SCIM appears to be more relevant for measuring the overall rehabilitation outcome rather than the hand function, and is most suitable for evaluating inpatient care. More recently, an increasing number of studies have used the disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand (DASH). The DASH is a generic instrument with no SCI-specific hand activities and no score of the use of aids;62 scoring the items may be difficult in SCI patients and some items are not at all applicable to SCI patients. Although some of the above scales might be able to discriminate between different motor levels of cervical SCI patients, information about the effects of arm–hand interventions on the actual activity pattern is insufficient.

The objective of the present paper is to describe the construction of a disease-specific questionnaire to evaluate interventions to the arm–hand of SCI tetraplegics. The questionnaire focuses on activities actually performed.

Material and methods

The procedure to develop the Tetraplegia Hand Activity Questionnaire (THAQ) questionnaire consisted of two phases (Figure 2). The first phase was item generation to gather all potential arm–hand function-related activities. In phase 2, the item list was reduced, while improving the technical formulation and selecting those items most sensitive to treatment effects.

Phase 1 – item generation: an empirical exploration

To collect arm–hand function-related activities of patients with tetraplegia due to SCI, two methods were used:

-

1)

Literature search: activities were selected from existing scales and the ICIDH.63 Of the existing scales, we used the QIF,54 functional independence measure (FIM)64,65 and rehabilitation activities profile (RAP).66

-

2)

Interviews: semi-structured interviews were held with 15 professionals a rehabilitation nurse, an occupational therapist and a rehabilitation physician from the Spinal Cord Unit in each of five rehabilitation centres in the Netherlands and Belgium, and five tetraplegic patients with an SCI. The participants received a list containing headings referring to all relevant activity domains. The participants had to indicate all hand-related activities of tetraplegic patients with an SCI, covering the daily activities of the patients.

This procedure of collecting relevant activities resulted in a list of items. A panel of eight rehabilitation physicians categorised these items into activity-homogeneous domains (Draft 1: see Figure 2).

Phase 2 – item reduction

In this phase, we used two methods to improve the Draft 1 item list and thereby reduce the number of items:

Technical construction

A technical screening of Draft 1 took place. The item list had to be unequivocal, nonoverlapping and adequately represent the arm–hand function. The questions had to be concisely stated and positively phrased. The research team and three test patients participated in the screening of the items.

Subsequently, to each item three scores (of ordinal level) were assigned (Table 1):

-

Performance: this score represents the difficulty in performing an activity.

-

Aid: this score assesses the utilisation of an aid.

-

Importance: this score shows the importance that the patient attributes to performing the activity independently.

These procedures resulted in Draft 2 of the item list (Figure 2).

Delphi method: expert panel judgment on item importance

The objective was to get an insight into the importance of the items, that is, they had to be sensitive to treatment effects of interventions to the arm–hand function of patients with a tetraplegic SCI. For this, a Delphi procedure67 with an expert panel was used. The expert panel comprised five rehabilitation physicians and five therapists, all experienced in rehabilitation treatment involving arm–hand interventions of tetraplegic SCI patients. The questionnaires were mailed.

The expert panel was consulted in rounds. The experts were independently asked to judge the importance of the items in terms of sensitivity to change after a surgical intervention and/or FES treatment. The experts could answer on a five-point Likert scale (ranging from 1=‘not important at all’ to 5=‘very important’). The panel members were stimulated to illustrate their judgements with examples derived from their clinical practice. For reasons of feasibility, we presented a restricted number of items to each member of the panel. Each expert was administered a randomised sample of, on average, 200 items. Each item was judged on importance by five out of 10 experts.

After these judgements, the items were ranked on importance. The experts’ judgements of the previous round were presented as feedback to the panel in the following round.

For the selection of important items to be included in the THAQ, an algorithm consisting of two predetermined decision rules was defined:

-

1)

An item was considered to be important if one panel member attributed the maximum score ‘5’ to that item and at least one other member judged that item with score ‘4’ or ‘5’.

-

2)

For the second decision rule we first applied a mathematical operation, intended to correct for bias of the individual experts. The discrepancies of the means of individual experts compared to the general mean per domain were taken into account. To this end, we adjusted the judgement scores by the ratio of general domain mean and the individual expert domain mean.

After correction for bias, three categories were defined:

-

Category A ‘to be included’: items considered of importance (score >3.5) by at least four of the five panel members

-

Category B ‘to be excluded’: items considered unimportant, that is, less than three of the five panel members scored >3.5 and no member scored ‘5’

-

Category C ‘to be reconsidered’: there was no consensus among the panel about the importance of these items. This category comprised all remaining items, that is, not assigned to category A ‘to be included’ or to category B ‘to be excluded’.

Applying these decision rules yielded the items of the first version of the THAQ.

Results

The results of the procedure to develop the THAQ are shown in Table 2.

Phase 1 – item generation

The literature search revealed 222 activities involving the arm–hand. In the 20 interviews (patients and professionals), 553 different activities were mentioned. Of these activities, 430 were not mentioned in the literature. This resulted in a list of 652 items. The panel of eight rehabilitation physicians categorised the activities of the item list in nine domains leading to Draft 1 of the item list. Table 2 shows that the largest domains in our literature search were household (50 items), self-care (41 items) and mobility (36 items). Few items were found in the domains work/administration/telecom (six items) and leisure (eight items), whereas in the interviews the largest domains were leisure (63 items), eating and drinking (56 items), self-care (55 items), continence (54) and household (53).

Phase 2 – item reduction

Technical construction

Table 2 shows that 243 items from Draft 1 were deleted or were combined with other items after the linguistic review and item construction (question together with answer options). We deleted items when the activity was part of a similar action to another item. For example, emptying a colostoma is similar to the activity of emptying an ileostoma. Items could also be combined with other items, for example, closing a shoe with an adaptation such as vicryl instead of ordinary shoelaces is seen as using an aid rather than as a separate activity. From the first Draft, 134 items were deleted either by combining them in the score of another item or because the activity was part of another item. Another 109 items were considered not strictly related to the arm–hand function and were therefore deleted. The proportional distribution of the items over the nine categories shows no major changes between Drafts 1 and 2. The technical construction resulted in a list of 409 items for further evaluation (Draft 2).

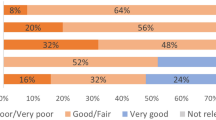

Delphi method

Draft 2 was presented to 10 experts. The panel judgements varied from 1 to 5 (most important). The importance scores 4 and 5 appeared in 44% of the judgements, and scores 1 and 2 in 37% of the judgements.

After two consultation rounds, the experts’ judgements stabilised. As no additional relevant information was expected from additional rounds, the iterative process was stopped. In the first decision rule, 60 items were qualified as relevant, and 93 items were qualified in the second decision rule. These 153 items were thus selected for the first version of the THAQ. The proportional distribution of the items over the nine categories is slightly different from Draft 1. Although leisure and household have slightly decreased, in the THAQ the experts’ judgement resulted in a selection of items for these categories, almost all describing new activities.

Table 2 shows that in the THAQ, eating and drinking (25) and self-care (22) have more items than household (10) and leisure (10). In the THAQ, 105 (69%) new items were identified generated in the interviews that were not mentioned in the QIF, FIM, RAP or ICIDH. For all categories, apart from self-care and dressing, at least half of the items are new and based on the interviews.

Discussion

Interventions to improve the arm–hand function of tetraplegic SCI are often complicated, expensive and time-consuming. Moreover, they require a careful outcome assessment. For these patients, we constructed a questionnaire (THAQ) to measure the effects of interventions on the arm–hand function.

We believe that, in addition to evaluation of impairments in body functions and structures and dexterity level, the outcome assessment on activity level is crucial. Although both questionnaires and dexterity tests are informative about activity level, dexterity tests estimate the functional capacity (can do), whereas in SCI the patient's actual performance (do do) is often quite different because of efficiency choices that the patient makes in daily life.56 Therefore, the THAQ focuses on activities that the patient actually does perform in daily life, rather than on activities that the patient can perform in a treatment setting.

To approximate the factors influencing the choices that the patient makes, some report the number of patients satisfied with the treatment result,70,71 but without elucidating the specific effects of the intervention that satisfy the patients. For our study group, the THAQ scores the importance attributed by the patients themselves to the ability to perform a particular activity.

A list of relevant activities was compiled by item generation and followed by item reduction, using relevant information from literature, clinical experts and patients.

The time needed to complete a patient interview with Draft 2 (409 items) was more than 1 h, obviously too long for practical use. Identification of redundant items was pursued; quantitative statistical methods such as Rash analyses or factor analyses would have required more than 200 tetraplegic SCI patients. As this is not feasible in the Netherlands, an expert panel judged the importance of the items using a qualitative analytical method, that is, the Delphi method.67

The Delphi study was performed on Draft 2. The Delphi method pursuits to achieve consensus in subsequent rounds of expert consultation. The experts were consulted using mailed questionnaires, which has advantages and disadvantages.68,69

Formal decision rules controlled the selection process. Although in the development of a clinical guideline a simple consensus decision rule suffices, in our search for relevant activities sensitive to change after interventions we applied a more complex algorithm consisting of two decision rules. In similar outcome studies, the sensitivity to change of outcomes measures at the activity level has been troublesome. Therefore, the choice of our first decision rule was to optimise the possibility of detecting a change in the activity level, aimed at an increase in responsiveness of the questionnaire. This rule implied that an item is considered important if one panel member reported, based on specific clinical experience, the maximum score ‘5’ and at least one other member confirmed this importance scoring ‘4’ or ‘5’. This decision rule utilised the best expertise of the individual panel members.

The second decision rule identified the items generally judged to be important. To avoid bias, we first applied the mathematical correction operation. These procedures generated the first version of the THAQ, consisting of 153 items. About 30–45 min are needed to complete this questionnaire during an interview.

Since the activities and handgrips of the SCI patients with a tetraplegia differ from other patient groups, they undermine the validity and sensitivity to change of generic outcome scales. To optimise these requirements for a new disease-specific outcome scale, a key role was reserved for the experience of both tetraplegic SCI experts and patients. The thorough construction process of the THAQ focused on the arm–hand function of the tetraplegic SCI patients, resulted in an activity scope different from the activities found in our literature search; 69% of the THAQ items were not generated by our literature search. The expert panel found activities relevant for evaluation in daily practice other than the activities covered in the literature; this underlines the additional value of the experts’ information. This particularly applies to the domains leisure, work/administration/telecom and continence, with 100, 88 and 87% new items, respectively. In our opinion, these three domains are of relatively high importance, because the patients value them in functioning independently. In contrast, for the activities in the domains self-care and dressing, which are well-covered in the literature, the patients frequently opt for the help of others.51,52,53

In the present study, attention was mainly paid to the content validity of the THAQ, using two separate steps in the construction process. Other aspects of the validity, such as the criterion and construct validity and the psychometric test properties, need further investigation.

References

Hanson RW, Franklin MR . Sexual loss in relation to other functional losses for spinal cord injured males. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1976; 57: 291–293.

Lamb DW, Chan KM . Surgical reconstruction of the upper limb in traumatic tetraplegia. A review of 41 patients. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1983; 65: 291–298.

Moberg E . The upper limb in tetraplegia: a new approach to surgical rehabilitation. Stuttgart: Thieme, 1978.

McDowell CL, Rago TA, Gonzalez SM . Tetraplegia. Hand Clin 1989; 5: 343–348.

Ditunno Jr JF, Stover SL, Freed MM, Ahn JH . Motor recovery of the upper extremities in traumatic quadriplegia: a multicenter study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1992; 73: 431–436.

Guttmann L . Spinal Cord Injuries: Comprehensive Management and Research, 2nd edn. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific, 1976.

Moberg E . Two-point discrimination test. A valuable part of hand surgical rehabilitation, e.g. in tetraplegia. Scand J Rehabil Med 1990; 22: 127–134.

Yarkony GM, Bass LM, Keenan Vd, Meyer Jr PR . Contractures complicating spinal cord injury: incidence and comparison between spinal cord centre and general hospital acute care. Paraplegia 1985; 23: 265–271.

Skold C, Harms-Ringdahl K, Hultling C, Levi R, Seiger A . Simultaneous Ashworth measurements and electromyographic recordings in tetraplegic patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998; 79: 959–965.

Priebe MM, Sherwood AM, Thornby JI, Kharas NF, Markowski J . Clinical assessment of spasticity in spinal cord injury: a multidimensional problem. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1996; 77: 713–716.

Doll U, Maurer-Burkhard B, Spahn B, Fromm B . Functional hand development in tetraplegia. Spinal Cord 1998; 36: 818–821.

Carroll SG, Bird SF, Brown DJ . Electrical stimulation of the lumbrical muscles in an incomplete quadriplegic patient: case report. Paraplegia 1992; 30: 223–226.

Harvey L . Principles of conservative management for a non-orthotic tenodesis grip in tetraplegics. J Hand Ther 1996; 9: 238–242.

House JH . Reconstruction of the thumb in tetraplegia following spinal cord injury. Clin Orthop 1985, 117–128.

House JH, Gwathmey FW, Lundsgaard DK . Restoration of strong grasp and lateral pinch in tetraplegia due to cervical spinal cord injury. J Hand Surg (Am) 1976; 1: 152–159.

Perkins TA, Brindley GS, Donaldson ND, Polkey CE, Rushton DN . Implant provision of key, pinch and power grips in a C6 tetraplegic. Med Biol Eng Comput 1994; 32: 367–372.

Hentz VR, Keoshian LA . Changing perspectives in surgical hand rehabilitation in quadriplegic patients. Plast Reconstr Surg 1979; 64: 509–515.

Waters RL, Sie IH, Gellman H, Tognella M . Functional hand surgery following tetraplegia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1996; 77: 86–94.

Harvey LA, Batty J, Jones R, Crosbie J . Hand function of C6 and C7 tetraplegics 1 - 16 years following injury. Spinal Cord 2001; 39: 37–43.

Nichols PJ, Peach SL, Haworth RJ, Ennis J . The value of flexor hinge hand splints. Prosthet Orthot Int 1978; 2: 86–94.

Jones RF, James R . A simple functional hand splint for C.5-6 quadriplegia. Med J Aust 1970; 1: 998–1000.

Freehafer AA . Tendon transfers in tetraplegic patients: the Cleveland experience. Spinal Cord 1998; 36: 315–319.

Crago PE, Memberg WD, Usey MK, Kelth MW, Kirsch RF, Chapman GJ, Katorgl MA, Perreault EJ . An elbow extension neuroprosthesis for individuals with tetraplegia. IEEE Trans Rehabil Eng 1998; 6: 1–6.

Curtis RM . Tendon transfers in the patient with spinal cord injury. Orthop Clin N Am 1974; 5: 415–423.

Abrahams D, Shrosbree RD, Key AG . A functional splint for the C5 tetraplegic arm. Paraplegia 1979; 17: 198–203.

Hage G . Brief or new: two pronation splints. Am J Occup Ther 1985; 39: 265–267.

Peckham PH, Kelth MW, Kilgore KL, Grill JH, Wuolle KS, Thrope GB, Gorman P, Hobby J, Mulcahey MJ, Carroll S, Hentz VR, Wlegner A . Efficacy of an implanted neuroprosthesis for restoring hand grasp in tetraplegia: a multicenter study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001; 82: 1380–1388.

McCarthy CK, House JH, Van Heest A, Kawiecki JA, Dahl A, Hanson D . Intrinsic balancing in reconstruction of the tetraplegic hand. J Hand Surg (Am) 1997; 22: 596–604.

Mulcahey MJ, Betz RR, Smith BT, Weiss AA, Davis SE . Implanted functional electrical stimulation hand system in adolescents with spinal injuries: an evaluation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1997; 78: 597–607.

Prochazka A, Gauthier M, Wieler M, Kenwell Z . The bionic glove: an electrical stimulator garment that provides controlled grasp and hand opening in quadriplegia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1997; 78: 608–614.

Saxena S, Nikolic S, Popovic D . An EMG-controlled grasping system for tetraplegics. J Rehabil Res Dev 1995; 32: 17–24.

Snoek GJ, IJzerman MJ, in ‘t Groen FA, Stoffers TS, Zilvold G . Use of the NESS handmaster to restore hand function in tetraplegia: clinical experiences in ten patients. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 244–249.

House JH, Comadoll J, Dahl AL . One-stage key pinch and release with thumb carpal-metacarpal fusion in tetraplegia. J Hand Surg (Am) 1992; 17: 530–538.

Waters R, Moore KR, Graboff SR, Paris K . Brachioradialis to flexor pollicis longus tendon transfer for active lateral pinch in the tetraplegic. J Hand Surg (Am) 1985; 10: 385–391.

Stenehjem J, Swenson J, Sprague C . Wrist driven flexor hinge orthosis: linkage design improvements. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1983; 64: 566–568.

Betz RR, Mulcahey MJ, Smith BT, Triolo RJ, Welss AA, Moynahan M, Keith MW, Peckham PH . Bipolar latissimus dorsi transposition and functional neuromuscular stimulation to restore elbow flexion in an individual with C4 quadriplegia and C5 denervation. J Am Paraplegia Soc 1992; 15: 220–228.

Kuz JE, Van Heest AE, House JH . Biceps-to-triceps transfer in tetraplegic patients: report of the medial routing technique and follow-up of three cases. J Hand Surg (Am) 1999; 24: 161–172.

Pham HN, Noble CN, Hentz VR . Rubber band as external assist device to provide simple grip for quadriplegic patients. Ann Plast Surg 1988; 21: 180–182.

Richardson D, Edwards S, Sheean GL, Greenwood RJ, Thompson AJ . The effect of botulinum toxin on hand function after incomplete spinal cord injury at the level of C5/6: a case report. Clin Rehabil 1997; 11: 288–292.

Dunkerley AL, Ashburn A, Stack EL . Deltoid triceps transfer and functional independence of people with tetraplegia. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 435–441.

WHO. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health – ICF. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2001.

Colyer RA, Kappelman B . Flexor pollicis longus tenodesis in tetraplegia at the sixth cervical level. A prospective evaluation of functional gain. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1981; 63: 376–379.

Hashizume C, Fukui J . Improvement of upper limb function with respect to urination techniques in quadriplegia. Paraplegia 1994; 32: 354–357.

Kiyono Y, Hashizume C, Ohtsuka K, Igawa Y . Improvement of urological-management abilities in individuals with tetraplegia by reconstructive hand surgery [In Process Citation]. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 541–545.

Brys D, Waters RL . Effect of triceps function on the brachioradialis transfer in quadriplegia. J Hand Surg (Am) 1987; 12: 237–239.

Gansel J, Waters R, Gellman H . Transfer of the pronator teres tendon to the tendons of the flexor digitorum profundus in tetraplegia. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1990; 72: 427–432.

Lo IK, Turner R, Connolly S, Delaney G, Roth JH . The outcome of tendon transfers for C6-spared quadriplegics. J Hand Surg (Br) 1998; 23: 156–161.

Jebsen RH, Taylor N, Trieschmann RB, Trotter MJ, Howard LA . An objective and standardized test of hand function. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1969; 50: 311–319.

Sollerman C, Ejeskar A . Sollerman hand function test. A standardised method and its use in tetraplegic patients. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 1995; 29: 167–176.

Stroh Wuolle K, Van Doren CL, Thrope GB, Keith MW, Peckham PH . Development of a quantitative hand grasp and release test for patients with tetraplegia using a hand neuroprosthesis. J Hand Surg (Am) 1994; 19: 209–218.

Welch RD, Lobley SJ, O’Sullivan SB, Freed MM . Functional independence in quadriplegia: critical levels. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1986; 67: 235–240.

Weingarden SI, Martin C . Independent dressing after spinal cord injury: a functional time evaluation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1989; 70: 518–519.

Rogers JC, Figone JJ . Traumatic quadriplegia: follow-up study of self-care skills. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1980; 61: 316–321.

Gresham GE, Labi ML, Dittmar SS, Hicks JT, Joyce SZ, Stehlik MA . The quadriplegia index of function (QIF): sensitivity and reliability demonstrated in a study of thirty quadriplegic patients. Paraplegia 1986; 24: 38–44.

Yavuz N, Tezyurek M, Akyuz M . A comparison of two functional tests in quadriplegia: the quadriplegia index of function and the functional independence measure. Spinal Cord 1998; 36: 832–837.

Marino RJ . Functional assessment in spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 1996; 1: 32–45.

Marino RJ, Goin JE . Development of a short-form Quadriplegia Index of Function scale. Spinal Cord 1999; 37: 289–296.

Marino RJ, Huang M, Knight P, Herbison GJ, Ditunno Jr JF, Segal M . Assessing selfcare status in quadriplegia: comparison of the quadriplegia index of function (QIF) and the functional independence measure (FIM). Paraplegia 1993; 31: 225–233.

Catz A, Itzkovich M, Agranov E, Ring H, Tamir A . SCIM – spinal cord independence measure: a new disability scale for patients with spinal cord lesions. Spinal Cord 1997; 35: 850–856.

Catz A, Itzkovich M, Agranov E, Ring H, Tamir A . The spinal cord independence measure (SCIM): sensitivity to functional changes in subgroups of spinal cord lesion patients. Spinal Cord 2001; 39: 97–100.

Meyers AR, Andresen EM, Hagglund KJ . A model of outcomes research: spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000; 81 (Suppl 2): S81–S90.

Hudak PL, Amadio PC, Bombardier C . Development of an upper extremity outcome measure: the DASH (disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand) [corrected]. The Upper Extremity Collaborative Group (UECG) [published erratum appears in Am J Ind Med 1996 Sep;30:372]. Am J Ind Med 1996; 29: 602–608.

WHO (ed.). International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Handicaps WHO 1980, Dutch translation ed, TNO 1981.

Granger CV, Hamilton BB, Keith RA, Zielezny M, Sherwin FS . Advances in functional assessment for medical rehabilitation. Top Geriatr Rehabil 1986; 1: 59–74.

Hamilton BB, Granger CV, Sherwin FS, Zielezny M, Tashman JS . A uniform national data system for medical rehabilitation. In: Fuhrer MJ (ed). Rehabilitation Outcomes: Analysis and Measurement. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co, 1987, pp 137–147.

van Bennekom CA, Jelles F, Lankhorst GJ, Bouter LM . The rehabilitation activities profile: a validation study of its use as a disability index with stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1995; 76: 501–507.

Linstone HA, Turoff M (eds). The Delphi Method: Techniques and applications. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1975.

Diehl M, Stroebe W . Productivity loss in brainstorming groups: towards the solution of a riddle. J Pers Soc Psychol 1987; 53: 497–509.

Murphy MK, Black NA, Lamping DL, McKee CM, Sanderson CFB, Askham J, Marteau T . Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technol Assess 1998; 2: 1–83.

Hentz VR, Brown M, Keoshian LA . Upper limb reconstruction in quadriplegia: functional assessment and proposed treatment modifications. J Hand Surg (Am) 1983; 8: 119–131.

Stroh Wuolle K, Van Doren CL, Bryden AM, Peckham PH, Keith MW, Kilgore MK, Grill JH . Satisfaction with and usage of a hand neuroprosthesis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80: 206–213.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank AH Bos for his constructive comments on this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Appendix. Examples of items of the THAQ

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Land, N., Odding, E., Duivenvoorden, H. et al. Tetraplegia Hand Activity Questionnaire (THAQ): the development,assessment of arm–hand function-related activities in tetraplegic patients with a spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 42, 294–301 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101588

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101588

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Internal consistency and validity of the Italian version of the Jebsen–Taylor hand function test (JTHFT-IT) in people with tetraplegia

Spinal Cord (2021)

-

Validation of the short version of the Van Lieshout Test in an Italian population with cervical spinal cord injuries: a cross-sectional study

Spinal Cord (2019)

-

Validation and cross-cultural adaptation of the Van Lieshout test in an Italian population with cervical spinal cord injury: a psychometric study

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2018)

-

Long-Term Urologic Evaluation Following Spinal Cord Injury

Current Bladder Dysfunction Reports (2016)