Key Points

-

This study shows that the Thermafil technique provides better results than cold lateral condensation if a corono-apical tapered preparation is made.

-

This technique may be used even if the apical part of the root canal is instrumented with .02 taper files.

-

The practitioner has to take into account the different tapers of both Thermafil and apical file by using a smaller diameter for the Thermafil obturator.

Abstract

Aim The aim of this in vitro study was to compare the marginal adaptation achieved by two obturation techniques (lateral condensation and Thermafil) using human teeth prepared by continuous rotation with the HERO 642® system.

Method The percentages of gaps and sealer on the root canal surface were determined by analysing the images of 12 sections per tooth. Tubule sealer penetration was assessed by backscattered scanning electron microscopy and energy dispersive spectrometry microanalysis.

Results The Thermafil obturation technique resulted in virtually no gaps and very low amounts of sealer on the root surface, unlike the lateral condensation technique. Tubule sealer penetration occurred with both techniques, but was deeper, especially in the mid and apical zones, with the lateral condensation technique.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obturation, the three-dimensional sealing of the entire root canal system, is the last step in endodontic treatment. The seal has to be perfect to protect the treated surface because while incomplete removal of aetiological factors is a major cause of endodontic treatment failure, according to Ingle,1 59% of failures can be attributed to apical percolation due to inadequate obturation.

No single currently available material is capable of providing a perfect root canal filling, which is why most techniques use several materials, the most common being a combination of gutta-percha and cement sealer. For best results, the gutta-percha is generally cold or heat condensed to force the cement sealer into the dentinal tubules.

Numerous techniques have been developed to try to improve marginal adaptation and reduce the thickness of the canal cement film to a minimum.2

Cold lateral condensation is a proven, classic technique. While one of the most widely used techniques, its effectiveness has often been called into question, with a number of studies reporting that lateral condensation results in non-homogenous obturation, poor adaptation of gutta-percha to canal walls, and gaps between the main and accessory cones.3,4,5 Brayton et al.,3 Goldman,6 and Torabinejad et al.7 have also reported that adaptation was relatively good in the coronal and apical zones with longitudinal gaps in the mid zone. However, this technique remains the 'gold standard' and most studies of new obturation systems use lateral condensation for comparison purposes.8,9,10,11

One of the most recent techniques, which uses central carriers pre-coated with thermoplasticised gutta-percha, seems to achieve an obturation that is as well adapted to the root canal system as is the lateral condensation technique.10,12 Certain studies have shown that the thermoplasticised gutta-percha technique is superior to other methods8,9,13,14,15 while others have reported that the carrier may remain exposed, thus creating gaps.5,7

The purpose of the work reported here was to conduct a comparative assessment of the sealing ability of the cold lateral condensation and Thermafil root canal obturation techniques using specimen teeth prepared by a rotary method.

Material and methods

Sixteen, freshly extracted, single-rooted human teeth were divided into two groups of eight teeth.

The root canals were prepared by continuous rotation using the HERO 642® system. This system uses Nickel-Titanium files with three tapers: 0.06, 0.04 and 0.02. These files are used in a crown down technique and each taper has a well-defined penetration level:

-

2/3 of the working length for the 0.06 taper files.

-

the working length minus 2 mm for the 0.04 taper files.

-

the exact working length for the 0.02 taper instruments.

These tapers exist in three apical diameters (20, 25 and 30), but the 0.02 taper files also exist in diameter 35 and 40. Different sequences have been described depending on the level of difficulty. In any case, whichever sequence we used, the last file was a 0.02 taper number 35 that ensures the placement of a 0.04 Thermafil N°30.

The root canals were irrigated with stabilised 3% sodium hypochlorite (3 ml total) between each instrumentation step. After the final instrumentation step, the root canals were ultrasonically irrigated for three minutes, followed by a one minute flush flow with 17% EDTA (2 ml), a hypochlorite rinse (3 ml), and a distilled water rinse (3 ml). The root canals were then dried.

The first group of teeth were obturated using the classic cold lateral condensation technique. The second group were filled using original 0.04 taper Thermafil obturators, according to the manufacturer's recommendations. For both techniques, a zinc oxide eugenol based sealer (Sealite, Pierre Rolland, France) was used.

Group 1: Cold lateral condensation

First, it was ensured that a 'B' Maillefer finger spreader (Maillefer, Dentsply, France) could be placed within 1 mm of the working length.

A gutta percha master cone 'B' Maillefer (Maillefer, Dentsply, France) was fitted to within 0.5 mm of the working length with tug back.

The inner walls of the root canal were coated with the sealer and the master cone was seated into place.

Lateral compaction was performed using accessory cones corresponding to the spreader.

Accessory cones were added until the spreader could not penetrate more than 2 mm into the root canal. The excess of gutta percha was removed with a warm instrument and vertically condensed.

Group 2: Thermafil

Thermafil verifiers were used to confirm that a size of 30 was the appropriate size to use.

A N°30 Thermafil obturator which corresponded to the verifier that fitted at the working length was selected.

A small amount of sealer was applied in the coronal part of the root canal and the heated obturator was positioned to the working length.

The plastic shank of the carrier was cut by using a thermacut bur (Maillefer, Dentsply, France).

For both groups, the access cavities were temporarily sealed with zinc oxide-calcium sulphate cement and the teeth stored in a humidified atmosphere for seven days.

The specimens were then fixed for 48 hours in 10% formaldehyde, dehydrated for four days in absolute alcohol, and dehydrated for 24 hours in acetone. The specimens were then placed in separate flasks containing glycol methyl methacrylate (GMA) and stored for 6 days at −20°C with one change of embedding medium. The specimens were transferred to freshly prepared cold resin in glass molds and left for two to three days at 4°C to allow the resin to polymerise.

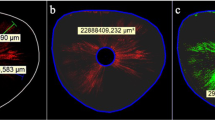

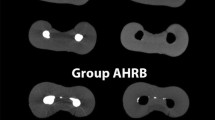

A microtome (LEICA SP 1600) operating at low speed was used to cut sections from the 16 embedded specimens. A water spray was used to prevent heat deformation of the obturation materials. Four 100-micron transverse sections were cut from the coronal, mid, and apical zones of each specimen. The sections were examined at 10x magnification using an optical microscope and photographs were taken for image analysis. The photographs were digitised with a 900 pixel per inch resolution and 256 colour scale. The images were then analysed by two observers using version 1.61 of the NIH (National Institutes of Health) image analysis software. A micrometer (690 pixels mm−1) was used for calibration purposes. Reproducible results were obtained through this calibration. The whole surface of the root canal and the surfaces covered with gutta-percha and sealer were measured in square millimeters. The locations of gaps were also noted.

The statistical analysis of image analyses was made using a nonparametric, unpaired Mann-Whitney test. This test is justified according the number of samples studied (N = 8).

Three sections were selected from each specimen (one from each zone: coronal, mid, apical) and prepared for scanning electron microscopic analysis and energy dispersive spectroscopy microanalysis. They were polished to a smoothness of approximately 6μ using 4000 grit silicon carbide paper disks. The specimens were then rinsed in alcohol and metallicised with a fine layer of gold-palladium by cathodic sputtering (Jeol JFC 1100).

Backscattered electron imaging (BEI) was performed using a Jeol JSM 6400 scanning electron microscope to obtain qualitative information about the chemical composition of the specimens.

Backscattered electrons are produced by the elastic interactions between the sample and the incident electron beam. These backscattered electrons are produced over a greater depth range and have higher energy, compared to secondary electrons.

The efficiency of production of backscattered electrons is proportional to the sample material's mean atomic number, which results in image contrast as a function of composition. Higher atomic number material appears brighter than low atomic number material.

At the same time, the specimens were analysed at 20 kv using an Oxford Link Isis energy dispersive spectroscopy system connected to the SEM. The Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectrometer (EDS) detects x-rays from the sample excited by the highly focused, high-energy primary electron beam penetrating into the sample.

The interaction of the high-energy electrons with the atoms in the sample causes shell transitions which result in the emission of an x-ray. The emitted x-ray has an energy characteristic of the parent elements present in the sample.

The EDS device detects elements with atomic numbers higher than or equal to 4 with a relative accuracy of 1% for a volume of 1μ3. We thus scanned for zinc (N=30), which is present in the sealer.

Results

The average of the areas of the root canal surface, gaps, and sealer for each zone were calculated, which enabled determination of the percentage of gaps and sealer with respect to the total root canal surface (Table 1).

The average percentage of gaps with respect to the canal surface in the coronal zone was significantly lower in specimens obturated using the Thermafil technique (0.66%) than those obturated using the cold lateral condensation technique (p = 0.0119). The average surface area covered by gaps was even lower in the mid zone for the specimens obturated using the Thermafil technique (0.08%), while it remained essentially the same for the specimens obturated using the cold lateral condensation technique (p = 0.0034). A significant difference was also noted in the apical zone, with 0% for the Thermafil and 2.16% (p = 0.05) for the lateral condensation technique.

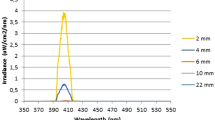

The average percentage of sealer areas with respect to the canal surface area was significantly lower in all three zones in specimens obturated using the Thermafil technique compared to those obturated using the lateral condensation technique. The results of the image analyses confirmed those obtained by BEI scanning electron microscopy. Very good marginal adaptation was observed in the mid (Fig. 1) and apical (Fig. 2) zones in specimens obturated using the Thermafil technique with intense areas of backscattering approximately 40 μm deep. The carriers were still surrounded by gutta-percha in the mid and apical zones. Almost total filling of an accessory canal can even be seen in the photograph of an apical section (Fig. 2). BEI photographs taken at higher magnifications (Fig. 3A) and EDS mapping of the zones (Fig. 3B) showed that there was total agreement between areas of intense backscattering and the presence of zinc in the tubules. BEI observations of coronal sections of specimens obturated using the cold lateral condensation technique revealed a number of gaps and no backscattering (Fig. 4). In the mid sections, (Fig. 5), despite the presence of gaps, numerous zones of backscattering (50 μm to 100 μm deep) were observed in the tubules. In the apical sections (Fig. 6), the seal appeared much better than in coronal and mid parts and backscattering areas have been observed as deep as 150 μm. A comparative assessment of BEI photographs taken at higher magnifications (Fig. 7A, 7B) once again showed that there was perfect agreement between areas of intense backscattering and EDS mapping, indicating that the sealer penetrated the tubules to depths of approximately 150 μm.

Discussion

Whatever the level, our study highlighted the significant superiority of the Thermafil obturation technique with respect to lateral condensation.

A key of clinical success is complete closure of the dentinal wall-obturation interface especially in the apical part to achieve the best apical seal. Most endodontic sealers are soluble and shrink slightly; so, it is best to rely as little as possible on sealers and more on gutta percha material.

Lateral condensation resulted in the gutta-percha covering an average 90.58% of the root canal surface in the coronal zone while the Thermafil technique resulted in 98.04% coverage. This percentage increased in the mid and apical zones for both techniques, attaining 93.07% apically for the lateral condensation technique and 98.38% for the Thermafil technique.

Interestingly, the percentage of sealer areas with respect to the root canal surface remained low (1.30% for coronal sections and 1.62% for apical sections) in specimens obturated with the Thermafil technique, compared to the percentages observed with the lateral condensation technique (6.43% for coronal sections and 4.77% for apical sections). The percentages remained similar and relatively high (6.43%, 5.83%, 4.77%) for the coronal, mid, and apical sections from specimens obturated using the cold lateral condensation technique.

Our study also confirmed the results reported by Gutmann et al.,13 Weller et al.,5 and Gençoglu et al.15,16 Gençoglu et al.16 used a similar approach but obtained lower gutta-percha percentages with the two techniques. This could be due to their irrigation protocol, which involved manual irrigation with 5.25% sodium hypochlorite without EDTA, while we used 3% sodium hypochlorite, ultrasonic irrigation, and a final flow flush with 17% EDTA, resulting in much cleaner root canal surfaces. Moreover, in a previous study, Gençoglu et al.14 showed that better gutta-percha adaptation is obtained with both obturation techniques when the smear layer is removed. But using again a similar approach in a recent study, Gencoglu et al.15 obtained nearly the same core material percentage in the apical part with the Thermafil technique.

Gaps were practically nonexistent with the Thermafil technique but were relatively numerous with the cold lateral condensation technique, especially in the mid sections. This is in agreement with the results reported by Torabinejad et al.;7 who described longitudinal voids in mid root sections of teeth filled by using cold lateral condensation.

Other studies have reported that lateral condensation is superior to the Thermafil obturation technique.12,17,18 In these stain penetration studies, the smear layer was not entirely removed. Barkins et al.18 used water irrigation and Chohayeb et al.17 and Lares et al.12 a low concentration (1%) of sodium hypochlorite. This point is important because Gençoglu et al.14 have shown that removing the smear layer improves the adaptation of thermoplasticised gutta-percha to the internal root canal wall more efficiently than for cold condensed gutta-percha, confirming the results of White et al.19

Zinc, which is a component of the sealer, was shown to be present in the tubules by EDS microanalysis, indicating that the obturation results in impregnation of dentinal tubules whichever technique was used. This seals the interface between filling material and dentine, and retention of the material might be improved by this mechanical locking. It should, however, be noted that the cold lateral condensation technique resulted in deeper penetration. This was especially so in the mid and apical sections. The pressure exerted by the spreader during the condensation procedure would thus appear to be much greater than that exerted by the conical carrier, which would explain the difference observed in the penetration depth.

In our study, the carriers remained surrounded by gutta-percha along their entire length, which is in disagreement with other authors, who have reported partial or total exposure of the carriers.5,20

This can be explained by the use of a crown down rotary method which allows a better regular corono-apical tapered preparation than if the whole root canal is instrumented with 0.02 taper instruments.

Although a 0.02 taper file number 35 was used to prepare the last 2 mm, the selection of a Thermafil number 30 prevented the stripping of gutta percha from the carrier.

In the previous studies,5,20 it should be also pointed out that the same diameter was chosen for the last apical file and the Thermafil obturator.

Consequently, the exposure of the carrier was ineluctable due to the different tapers of both the apical file and the obturator.

In our study, despite the fact that the teeth have not been randomly allocated into groups, the results obtained with the Thermafil technique were clearly superior to those obtained by lateral condensation using the same preparation procedure. The Thermafil technique resulted in filling of accessory canals with gutta-percha and not with sealer as it was observed by using cold lateral condensation technique. Whilst the study could not be blinded due to the presence of the Thermafil carrier, the between group differences were clear and objectively measured, therefore the likelihood of examiner bias is extremely low.

References

Ingle JI . Endodontics. 4th ed. pp 228–307. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1994.

Al Rafei S R, Sayegh F S, Wright G . Sealing ability of a new root canal filling material. J Endod 1982; 8: 152–153.

Brayton SM, Davis SR, Goldman M . Gutta-percha root canal fillings. An in vitro analysis. I. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1973; 35: 226–231.

Kersten HW, Fransman R, Thoden van Velzen SK . Thermomechanical compaction of gutta-percha. II. A comparison with lateral condensation in curved root canals. Int Endod J 1986; 19: 134–140.

Weller RN, Kimbrough WF, Anderson RW . A comparison of thermoplastic obturation techniques: adaptation to the canal walls. J Endod 1997; 23: 703–706.

Goldman M . Evaluation of two filling methods for root canals. J Endod 1975; 1: 69–72.

Torabinejad M, Skobe Z, Trombly PL, et al. Scanning electron microscopic study of root canal obturation using thermoplasticized gutta-percha. J Endod 1978; 4: 245–250.

Fabra-Campos H . Experimental apical sealing with a new canal obturation system. J Endod 1993; 19: 71–75.

Gulabivala K, Holt R, Long B . An in vitro comparison of thermoplasticised gutta-percha obturation techniques with cold lateral condensation. Endod Dent Traumatol 1998; 14: 262–269.

Abarca AM, Bustos A, Navia M . A comparison of apical sealing and extrusion between Thermafil and lateral condensation techniques. J Endod 2001; 27: 670–672.

Goldberg F, Artaza LP, De Silvio A . Effectiveness of different obturation techniques in the filling of simulated lateral canals. J Endod 2001; 27: 362–364.

Lares C, el Deeb ME . The sealing ability of the Thermafil obturation technique. J Endod 1990; 16: 474–479.

Gutmann JL, Saunders WP, Saunders EM, Nguyen L . A assessment of the plastic Thermafil obturation technique. Part 1. Radiographic evaluation of adaptation and placement. Int Endod J 1993; 26: 173–178.

Gencoglu N, Samani S, Gunday M . Dentinal wall adaptation of thermoplasticized gutta-percha in the absence or presence of smear layer: a scanning electron microscopic study. J Endod 1993; 19: 558–562.

Gencoglu N, Garip Y, Bas M, Samani S . Comparison of different gutta-percha root filling techniques: Thermafil, Quick-fill, System B, and lateral condensation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2002; 93: 333–336.

Gencoglu N, Gunday M, Bas M, Basaran B . A comparative study of the area of the canal space obturated by thermoplasticized gutta-percha techniques. J Marmara Univ Dent Fac 1994; 2: 441–446.

Chohayeb AA . Comparison of conventional root canal obturation techniques with Thermafil obturators. J Endod 1992; 18: 10–12.

Barkins W, Montgomery S . Evaluation of Thermafil obturation of curved canals prepared by the Canal Master-U system. J Endod 1992; 18: 285–289.

White RR, Goldman M, Lin PS . The influence of the smeared layer upon dentinal tubule penetration by plastic filling materials. J Endod 1984; 10: 558–562.

Juhlin JJ, Walton RE, Dovgan JS . Adaptation of thermafil components to canal walls. J Endod 1993; 19: 130–135.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Guigand, M., Glez, D., Sibayan, E. et al. Comparative study of two canal obturation techniques by image analysis and EDS microanalysis. Br Dent J 198, 707–711 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812389

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812389

This article is cited by

-

A comparison of obturation techniques

British Dental Journal (2005)