Key Points

-

During the first six weeks of treatment, the occlusal surface of the splint made no significant contribution to any of the outcomes measured suggesting that the occlusion is a relatively unimportant factor influencing recovery in the majority of TMD patients seen in practice.

-

A small proportion of patients needed treatment for up to five months to obtain a satisfactory response. These were the patients who crossed over from the non-occluding control splint to the stabilising splint. They tended to be older with TMJ clicking.

-

Clicking was not especially responsive to treatment with the stabilising splint, but discomfort was reduced in three quarters of patients with clicking TMJs. It was difficult to make a reliable diagnosis of disc displacement with reduction using the trial criteria.

-

Suitably trained and interested GDPs can manage four out of five TMD patients in general practice; a link with specialist services is recommended to deal with non-responding patients.

Abstract

Introduction Little is known about how effective general dental practitioners (GDPs) are in treating temporomandibular disorders (TMD). The overall aim of this study was to compare the lower stabilising splint (SS) with a non-occluding control (CS) for the management of TMD in general dental practice.

Method A total of 93 TMD patients attending 11 GDPs were randomly allocated to SS or CS. Diagnosis was according to International Headache Society Criteria. Outcome criteria included pain visual analogue scale (VAS), number of tender muscles, aggregate joint tenderness, inter-incisal opening, TMJ clicks and headaches. Splints were fitted one week after baseline and patients were followed-up every three weeks to three months; those not responding to CS after six weeks (< 50% VAS reduction) were crossed over to SS for a further three months.

Results Documentation was returned from nine GDPs for 72 patients (38 for SS, 34 for CS). At six weeks, mean improvements were noted for all outcome criteria, but less so for clicking. There were no significant differences between splints [χ2]. Seventeen CS patients had < 50% VAS reduction and were provided with SS in the cross-over group. CS patients with >50% VAS reduction were significantly younger than CS patients who crossed-over (ANOVA, p=0.009) and had significantly less diagnoses of TMJ clicking (χ2, p<0.05). At the conclusion of the trial 16 patients were referred for specialist management: 11 non-responders (< 50% VAS reduction), one of whom needed occlusal adjustment and five responders also needing occlusal adjustment.

Conclusions At six weeks SS gave similar relief to CS for all outcome criteria. Patients who crossed-over from CS to SS were more likely to be older and have clicking TMJs. At the end of treatment nine of 11 non-responders to SS had a diagnosis of disc displacement with reduction. However, 80% TMD patients were managed effectively by GDPs using splints for periods of up to five months

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Temporomandibular disorders (TMD) comprise a spectrum of conditions affecting the temporomandibular joints and muscles of mastication. These musculo-skeletal conditions have similar signs and symptoms including pain, limitation of movement, joint noises (clicking and crepitus), incoordination, headaches and occasionally tinnitus. In recent years, specific diagnostic criteria for sub-diagnoses of TMD have been introduced,1,2,3 but most dentists may be more familiar with catch-all terminology such as 'temporomandibular joint dysfunction syndrome', facial arthromyalgia or Costen's Syndrome.

Dentists are extensively involved in the management of TMD, although it must be recognised that we are not the only discipline to do so. In the UK, general dental practitioners (GDPs) and general medical practitioners have traditionally referred patients to hospitals, dental hospitals or specialist centres. However, some GDPs do provide treatment in their practices but effectiveness is not well documented as controlled studies have always been carried out in hospitals or universities.

Dental management of TMD treatment often involves occlusal splints and occlusal adjustment. A critical review has found that occlusal splints may be of benefit in TMD, but there is little evidence for the use of occlusal adjustment.4 Occlusal splints are usually designed to cover the occlusal surfaces of the teeth and many consider the resulting change in occlusion to be responsible in part or in total for the therapeutic effect. Whilst there are a number of different splint designs, the two used most commonly which attempt to effect a planned occlusal change are the stabilisation splint and the anterior repositioning splint.5 The stabilisation appliance is generally indicated for TMD related to muscle hyperactivity and joint pain whereas the anterior repositioning splint is generally indicated for disc displacement disorders resulting in clicking and intermittent locking of the TMJs.5

Whilst it would be expected that the stabilisation splint would show a clear-cut benefit over a non-occluding control, clinical studies making this comparison have shown equivocal results. In randomly controlled studies Dao6 reported no difference between splints, Rubinoff7 a minor difference and Ekberg8 that the stabilising splint was significantly better than the control.

In the early 1990s a study group of GDPs interested in occlusal management decided that they wanted to find out how effective the stabilising splint was in treating TMD9 in general dental practice. A research grant was successfully applied for and links established with the local university. In order that effectiveness could be assessed in relation to the splint's occlusal surface, a simple audit project was abandoned in favour of a randomly controlled trial.

In designing the study it was decided that a broad spectrum of patients, representative of TMD patients presenting in general practice, should be included. It was acknowledged at the outset that TMD specialists might use different treatments or splint designs depending on sub-diagnosis of TMD, personal preference and experience. However, as evidence based guidelines to the choice of treatment are not well established and because of the difficulty in diagnosing disc displacements which would be amenable to anterior repositioning splint treatment, the stabilising splint or non-occluding control were used for all included categories of patient.

This study had three aims:

-

1

To directly compare a lower stabilising splint with a non-occluding control splint when used short-term in general dental practice. It was hypothesised that the stabilising splint would give a significantly better response than the control splint for each of the outcome measures assessed (Table 1).

-

2

To make a preliminary analysis of differences in patients who responded and those who did not respond to treatment with a control splint. 'Non-responding' was defined as less than a 50% reduction of original pain.

-

3

To determine the proportion of patients in need of referral to the dental hospital for further management after the trial and their diagnoses.

Materials and methods

Eleven GDPs were originally involved at the inception of the trial, which was approved by five separate ethics committees according to the location of the practice in the region around Newcastle. These dentists had attended a training day to standardise examination and splint fitting techniques and nine of them remained actively involved throughout the trial.

A total of 93 patients were entered into the trial between February 1994 and the end of July 1996. The inclusion criteria were:

-

Aged 18 and over

-

Pain in TMJ or muscles or both plus one or more of the following:

-

joint sounds (clicking or crepitus)

-

a history of jaw locking or limitation of opening

-

muscle tenderness to palpation

-

TMJ tenderness to palpation

-

Symptoms present for >4 weeks

-

Sufficient teeth to support and occlude against a lower splint.

Patients who were dentists were excluded or if they attended as an emergency in acute pain and dysfunction requiring immediate treatment; for example from trauma or an acute disc displacement without reduction. Patients were also excluded if they were not prepared to co-operate with the trial requirements. The source of patients included the dentists' own practices (40%), referred from another practice (41%), self referred from another practice (13%) and a small number from the local dental hospital (6%). Patients were not charged for treatment.

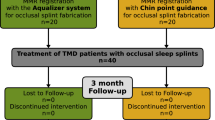

A schematic diagram of the trial, a unilateral crossover design, is shown in Fig. 1 Patients were randomly allocated either to the non-occluding control or stabilising splint. Of the original 93 patients 21 were lost to follow-up:

-

14 patients did not have forms returned by two dentists who withdrew from the trial

-

five patients failed to complete treatment

-

two patients decided not to start treatment.

The trial was designed to allow non-responding patients (less than 50% pain reduction) allocated to the control splint to be identified at six weeks and be crossed over to the stabilising splint at nine weeks. In the stabilising splint group, if a patient was a non-responder after the second adjustment appointment they were sent to the dental hospital for a hospital consultant to check splint adjustment. Any patient deemed a non-responder at the end of the trial was sent to the dental hospital to see the same consultant for further management. Arrangements were made for patients who responded to treatment to be reviewed after one year in practice.

At the first appointment a provisional diagnosis was made of TMD, the nature of the trial explained and written consent obtained. The dentist contacted the trial co-ordinator whose nurse registered the patient and randomly allocated either a stabilising splint or non-occluding control. It should be noted that the random allocation of splints was predetermined for each GDP using a permuted block of ten. This approach ensured that those dentists who saw the maximum of ten patients each would fit five stabilising splints and five controls. All dentists were blind to the allocation until the patient was registered into the trial. Letters were then sent to doctors and dentists informing them of their patients' involvement.

At the second appointment (baseline) the patient completed a de-tailed proforma in the waiting room covering the following aspects:

-

Pain intensity both currently and over the previous week

-

Current medication

-

Headache frequency

-

Visual or aural disturbance

-

Neurological symptoms (dizziness, numbness, tingling)

-

Other musculo-skeletal symptoms (back, shoulders or neck)

-

Any diagnosis of arthritis (rheumatoid or osteo arthritis)

-

History of trauma to head and neck

-

Diurnal and nocturnal parafunctional activity

-

Awareness of anxiety or depression and any related treatment

-

Any stress related illnesses

-

Major life events in the previous 12 months

The proforma usually took about 20 minutes to complete and was self explanatory to most patients, however any questions they found unclear or had not been answered could be discussed later with the dentist. A detailed history and examination were made in the surgery, also with the aid of a proforma, which included:

-

Current complaints

-

Pain history

-

Clicking and locking history.

The extra-oral examination detailed:

-

Muscle tenderness scored as either present or absent and any trigger points identified. The muscles palpated are listed in Fig 5. A simple electronic balance helped dentists standardise the amount of palpation force required (1Kg force extra-orally, 0.5Kg force intra-orally)9

-

TMJ tenderness (laterally, posteriorly and on movement) scored as either present or absent

-

TMJ clicking (assessed by palpating laterally over each TMJ during opening and closing)

-

TMJ crepitus

-

Maximum interincisal opening (measured with a steel rule) both comfortable and despite discomfort

-

Maximum lateral excursions

-

Deviation on opening

The intra-oral examination detailed:

-

Evidence of parafunction (bruxo-facets, cheek and tongue ridging)

-

A full occlusal examination.10

Dr Wassell and Dr Adams reviewed the forms at a later stage to establish a diagnosis derived from criteria developed in collaboration between the International Headache Society2 and the American Academy of Craniomandibular Disorders.3 The key clinical criteria for assigning a sub-diagnosis related to muscle problems, joint problems or both are shown in Table 2. It was not possible to subject patients with clicking TMJs to soft tissue imaging.

Patients were provided with a pain diary to be filled in on a daily basis and two psychological inventories: the Beck Hopelessness and Spielberger Trait Anxiety tests. Analyses of this data will form the subject of another paper as will details of the occlusal analysis.

Alginate maxillary and mandibular impressions were recorded along with a wax (Moyco Extra Hard Beauty Wax, Prestige Dental Products, UK) retruded record at a vertical separation approximating to the thickness of a stabilising splint. Patients' mandibles were manipulated bimanually in an attempt to achieve centric relation. A facebow (Denar Slidematic, Prestige Dental Products, UK) facilitated mounting on a semi-adjustable articulator. Major undercuts were blocked out before the splints were waxed. To ensure consistency, this approach was used for both the stabilising and the non-occluding control.

One technician from a commercial laboratory made both appliances from heat-cured acrylic according to detailed instructions:

-

Stabilising appliance: The mandibular splint was designed to provide anterior guidance and anterior occlusal stops only. After mounting, the incisal pin was adjusted to give an adequate thickness of acrylic (approximately 1 — 1.5 mm) between the posterior teeth. The splint was waxed to leave the posterior teeth just out of contact so that self-cured acrylic could be applied to the splint during clinical fitting thus giving multiple even points of occlusal contact.

-

Non-occluding control splint: This was essentially a lingual flange of acrylic extending from the occlusal or incisal surfaces into the lingual sulcus.

At the third appointment, usually one to two weeks later, the splint was fitted. As stated above, stabilising splints had their occlusal surfaces relined posteriorly with self-cured acrylic using a hydroflask to reduce porosity during curing. After the acrylic had set, the posterior occluding areas were ground flat and polished leaving only point contacts against opposing functional cusp tips. The occlusion on the splint was refined using red and black occlusal foils (GHM Hanel, Prestige Dental Products, UK) held in Miller's forceps (Fig 2). Care was taken to ensure that the control splint did not involve any occlusal contacts and was a snug fit. Instructions were given to wear the splints full-time but to leave out at mealtimes. The importance of good splint hygiene and oral hygiene was stressed before patients were dismissed.

Patients were reviewed every three weeks until the end of treatment. At each review the pain VAS and detailed examination were repeated so that the outcome variables outlined in Table 1 introduction could be quantified. Again, the patient completed the VAS in the waiting room to reduce bias. Treatment lasted either 12 weeks, for stabilising and control groups, or 21 weeks for control group patients who crossed over. At the end of this period, patients were advised to use their splints at night only, or as required, but attempt if possible, to reduce wear gradually. Any non-responders (<50% pain reduction) were referred for further management at the dental hospital, as were patients who requested referral or were deemed to require occlusal adjustment. Patients were re-diagnosed by the receiving consultant using the same criteria described above. Occlusal adjustment was indicated if at the end of treatment, splint removal resulted consistently in:

-

1

The return of pain with evidence of occlusal interference

-

2

The patient's awareness of an uncomfortable occlusion.

All data were transcribed into a Minitab Spreadsheet. To determine any differences at baseline between the control and stabilising groups χ2 or ANOVA tests were used, as appropriate, for each of the outcome variables with p < 0.05 taken as the level of significance. At six weeks, any differences between the control group and stabilising splint groups were examined using χ2 or ANOVA for each outcome variable. A comparison of patients with control splints who crossed-over and those who did not was also made using χ2 or ANOVA for each outcome variable. In addition these two groups were compared for age and duration of symptoms before treatment.

Results

There were 778 patients who started treatment, 69 female and 9 male. The mean age of the control group was 35.9 (s.d. 10.3) and that of the stabilising splint group 37.9 (s.d. 12.6). This difference was not statistically significant. TMD diagnoses, categorised under either 'muscle' or 'joint' or 'both' according to International Headache Society Criteria, are displayed in Table 3. Subsequent data refer to those 72 patients who completed treatment.

Comparison of stabilising splint and control at six weeks

Graphs showing how the three groups 'control splint', 'crossover' and 'stabilising splint' changed with time in respect of mean values for each outcome variable are displayed in Figs. 3,4,5,6,7,8. There were no significant differences between the control and stabilising splint groups at baseline. At 6 weeks, control and stabilising splints had similar improvements for all outcome variables with no significant differences between groups. The reader should note that the apparent improvement of the control group between weeks 6 and 9 is due to the non-responders having moved to the crossover group.

Preliminary analysis of responders and non-responders to the control splint

In each of the graphs a dotted line appended to the crossover group shows how these patients were affected between baseline and crossover. In this way, apparent differences at baseline from the control group as a whole and the stabilising group could be identified. The only apparent difference was in the percentage of patients with clicking. For this outcome variable a significant difference (χ2 p < 0.05) at baseline was found, revealing that control patients who crossed-over had significantly more diagnoses of clicking (13 of 17) than those who did not (8 of 19). Also, control patients who crossed over were significantly older (mean 41, s.d. 12) than those who did not (mean 31, s.d. 9) (ANOVA p=0.009). Although there was a trend for crossover patients to have had TMD symptoms for longer (mean 60 months, s.d. 76 months) than the responding control patients (mean 30 months, s.d. 44), this was not significant.

Referral of patients to the dental hospital

Two patients were referred to the dental hospital early in the trial to have their splint adjustment checked. At the end of the trial only 11 patients had to be referred as non-responders for further management. Of these, two had been entered into the trial but data had not been returned for them. A further patient had been misdiagnosed with a periapical abscess and possibly atypical facial pain. The consultant receiving the patients provided diagnoses as shown in Table 4.

Referrals for occlusal adjustment were made in respect of one non-responder and five responding patients.

Discussion

Before discussing the results it is worth emphasising that the dentists involved in this study were well qualified to do so. They had all attended one or more postgraduate occlusion courses and, as members of the Newcastle Occlusion Study Group, had investigated the background of TMD whilst preparing for the study in conjunction with a senior lecturer in restorative dentistry, a statistician and a behavioural scientist.

The trial was designed to consider the broad spectrum of TMD conditions that present in general dental practice rather than focus on a particular category eg myofascial pain. As mentioned in the introduction, it was recognised at the outset that some patients may respond better than others to stabilising splint treatment, but as discussed below the diagnostic categories are often not clear-cut. Hence, our approach was to attempt a diagnosis and then observe those patients who responded and those who did not. Patients entered into the trial had levels of pain and other TMD symptoms in line with patients treated in specialist centres.11 Outcome measures were chosen to give a more objective assessment of change than simply asking patients whether they felt better or not.

Comparison of stabilising splint and control at six weeks

The participating dentists were surprised that control splints gave similar results to stabilising splints for all outcome measures at six weeks. However, two out of three other randomly controlled studies which have compared the stabilising splint with a non-occluding control have shown both appliances equally effective.6,7 In these two studies patients were all diagnosed with myofascial pain. There has been only one study that showed the stabilising splint to be significantly better than a control splint.8 In that study, patients were all diagnosed with moderate to severe arthrogenous pain, scoring a VAS greater than 6 out of 10. In our study patients were diagnosed with a variety of muscle and joint disorders but 68 out of 72 (95%) had a diagnosis of pain of muscular origin, either myofascial pain or reflex splinting. Hence it is not surprising that our results fit in with two of the three previous studies showing no significant difference between controls and stabilising splint. These results serve to illustrate that for the majority of TMD patients seen in practice the occlusal surface of the splint is relatively unimportant during the early part of treatment.

It is worth emphasising that whilst the control splint did not in any way involve the occlusal surfaces it would be incorrect to think of it merely as a placebo. The presence of the lingual flange may have had an influence on tongue position and oral perception. However, temporomandibular disorders in general can be self limiting and it is possible that some patients in both groups could have shown improvement spontaneously rather than this being solely down to the result of treatment.

Preliminary analysis of responders and non-responders to the control splint

The control splint was not effective for all patients; 17 out of 36 patients had less than a 50% reduction in pain at six weeks and were accordingly crossed-over to the stabilising splint. These patients had significantly more diagnoses of painful clicking joints (13 of 17) compared with responders to the control splint (8 of 19). They were also on average ten years older than the patients who responded to the control splint.

After a further 12 weeks of treatment with the stabilising splint only four patients in the crossover group remained non-responders. This finding supports the use of the stabilising splint for patients with clicking and arthralgia. However it is not clear from our study whether these non-responders also benefited from the extended length of treatment or why they fell into an older age group. It may be simply as a result of younger patients responding faster to treatment or the fact that TMJ pain is often resistant to splint therapy.12

There is evidence that prolonged treatment of whatever type can be beneficial for some patients.13 Also, the same extensive review has shown that both placebo and active treatments are significantly better than no treatment at all.13 Another question that needs to be answered is whether these short-term improvements are maintained in the longer term.

In our study the relationship between treatment outcome and variables, such as age, signs and symptoms at the start of treatment, were determined by a preliminary analysis. There are sure to be other variables, which may be associated with outcome and there may be interactions between them. Future studies will need to test candidate variables, such as those identified in this one using multivariate analysis.

Referral of patients to the dental hospital

The number of patients effectively treated in practice was encouraging: only 11 out of the 77 patients starting treatment (14%) were referred to the dental hospital as non-responders. It is worth emphasising that none of the patients having >50% pain reduction asked for onward referral suggesting this was a clinically acceptable reduction. Reassuringly, only one patient was misdiagnosed and one patient had a systemically associated condition, rheumatoid arthritis (Table 4). One of the non-responders required occlusal adjustment and a further five responding patients (6%) were referred for occlusal adjustment alone. These findings imply that four out of five TMD patients can be managed by knowledgeable GDPs using reversible treatment. As patients are more likely to be seen quickly in practice this approach should be encouraged, leaving the specialist centres to deal with more intractable cases and those with diagnostic difficulties. Of course issues of training and suitable remuneration would need to be resolved before this approach became universally applicable but it would be a desirable goal to achieve.

Table 4 shows that nine of the 11 non-responding patients had a diagnosis of disc displacement with reduction suggesting that the stabilising splint was relatively ineffective in controlling pain for approximately one quarter of patients diagnosed with this problem. The relative ineffectiveness of stabilising splints in treating disc displacement with reduction has been described previously.14 Nevertheless, although these patients had a click on opening and closing, the degree of click reproducibility was not defined and only one patient referred to the dental hospital fell clearly into the category of requiring an anterior repositioning splint (ie elimination of the click and improvement in comfort by forward mandibular posture).15

In total, six patients were referred for occlusal adjustment. While the literature does not support occlusal adjustment as a general treatment for TMD, it is the authors' clinical experience that a small minority of patients do benefit who fit the criteria mentioned in the method. Perhaps future studies of occlusal adjustment should concentrate on such specifically selected groups of patients.

Trial critique

This study may be criticised on the basis of the trial design, diagnostic criteria, drop out rate and the fact that the clinical assessments were not made blind to treatment allocation.

Trial design

The unilateral crossover design arose out of concern from one of the ethics committees that patients suffering from cranial or facial pain may be compromised if left too long on what may be an ineffective treatment. A bilateral crossover would have been preferable but the study still provides useful and valid information regarding splint treatment.

Diagnostic criteria

Increasingly dentists are attempting to sub diagnose TMD for research and treatment purposes. At the time the trial was designed we chose the diagnostic criteria produced by the collaboration of the International Headache Society2 and the American Academy of Craniomandibular Disorders.3 These criteria are helpful in distinguishing between sub diagnoses of TMD and have been used as the basis of more precisely defined Research Diagnostic Criteria1 which a number of recent trials have used.16 However, there are occasionally grey areas with both of these classifications where it is difficult to distinguish clearly between two sub diagnoses. For instance, a patient with an intermittent click and painful masticatory muscles may be put into the category of myofascial pain if he or she did not exhibit clicking at the time of the appointment. However, if the clinician recorded relatively reproducible clicking at the time of the appointment, a diagnosis of disc displacement with reduction plus myofascial pain would be made. This type of diagnostic problem does not negate the value of these criteria but emphasises that clinicians need to be careful that they are not too dogmatic about the treatment they prescribe on the basis of the diagnosis alone, especially where it is not clear-cut.

Drop out rate

In a large study of this type some drop out of patients can be expected. In the same way when a large group of researchers is involved over a long period, not all of them are able to remain connected, and allowance for this should be built in from the beginning. In our case, input was lost from two GDPs. This was disappointing as more than twice as much data (14 patients) was lost from GDP withdrawal than from patients failing to start or complete treatment (7 patients). However a critical mass of 12 researchers was maintained: nine dentists, a technician, a clinical academic and a statistician.

Not a blind study

It could be argued that it would be easier to control a study of this type in an institutional setting but this would have defeated the aim of assessing outcome in general dental practice. Whilst it was not practical in this study to arrange double blind assessment of treatment outcome, as mentioned previously, considerable attention was paid to eliminating bias and variation. A calibration day was arranged before the study started, to ensure consistent approaches to measurement and splint construction. Pain measurements were taken in the waiting room so that direct contact with the dentist did not influence patient response. The same technician made all the splints according to a set protocol and finally patients were not charged for treatment in case variations in patient fees influenced results.

Conclusions

At six weeks there were no significant differences between lower stabilising splints and non-occluding controls for any of the outcome variables measured.

At six weeks, preliminary analyses showed non-responding patients in the control group were significantly older and had significantly more diagnoses of TMJ clicking than patients who responded to treatment.

At the end of the trial, nine of 11 patients referred as non responders had a diagnosis involving disc displacement with reduction, but 75% of patients in the trial with this diagnosis had responded to treatment.

When interested and suitably trained, general dental practitioners can manage four out of five TMD patients with reversible treatment in their own practices.

References

Dworkin SF, LeResche L . Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: review, criteria, examinations and specifications, critique. J Craniomandib Disord 1992; 6: 301–355.

Oleson J . Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain. Cephalgia. Olso: Norwegian University Press, 1988.

American Academy of Craniomandibular Disorders. In: McNeill C. (ed.) Craniomandibular disorders: guidelines for evaluation, diagnosis and management. Chicago: Quintessence, 1990.

Forssell H, Kalso E, Koskela P, Vehmanen R, Puukka P, Alanen P . Occlusal treatments in temporomandibular disorders: a qualitative systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Pain 1999; 83: 549–560.

Okeson JP . Management of temporomandibular disorders and occlusion. 4th Edition. St Louis: Mosby, 1998. pp. 474–487.

Dao TT, Lavigne GJ, Charbonneau A, Feine JS, Lund JP . The efficacy of oral splints in the treatment of myofascial pain of the jaw muscles: a controlled clinical trial. Pain 1994; 56: 85–94.

Rubinoff MS, Gross A, McCall WD, Jr . Conventional and nonoccluding splint therapy compared for patients with myofascial pain dysfunction syndrome. Gen Dent 1987; 35: 502–506.

Ekberg EC, Vallon D, Nilner M . Occlusal appliance therapy in patients with temporomandibular disorders. A double-blind controlled study in a short-term perspective. Acta Odontol Scand 1998; 56: 122–128.

Nichols WP, Dookun R . Research in general practice—the germination of an idea. Br Dent J 1998; 185: 220–222.

Steele JG, Nohl FS, Wassell RW . Crowns and other extra-coronal restorations: occlusal considerations and articulator selection. Br Dent J 2002; 192: 377–380, 383–387.

Okeson JP . Management of temporomandibular disorders and occlusion. 4th Edition ed. St Louis: Mosby, 1998. pp. 357–358.

Major PW, Nebbe B . Use and effectiveness of splint appliance therapy: review of literature. Cranio 1997; 15: 159–166.

Feine JS, Lund JP . An assessment of the efficacy of physical therapy and physical modalities for the control of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain 1997; 71: 5–23.

Santacatterina A, Paoli M, Peretta R, Bambace A, Beltrame A . A comparison between horizontal splint and repositioning splint in the treatment of 'disc dislocation with reduction'. Literature meta-analysis. J Oral Rehabil 1998; 25: 81–88.

Gray RJM, Davies SJ, Quayle AA . A clinical approach to temporomandibular disorders: 6 Splint therapy. Br Dent J 1994; 170: 135–142.

Dworkin SF, Huggins KH, Wilson L, Mancl L, Turner J, Massoth D et al. A randomized clinical trial using research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders-axis II to target clinic cases for a tailored self-care TMD treatment program. J Orofac Pain 2002; 16: 48–63.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the British Dental Association Research Foundation for sponsoring this project through the Shirley Glasstone Hughes Memorial Prize. In particular the authors are deeply indebted to Professor Jack Rowe for his wise counsel and encouragement during the application process. Pivotal to the success of this study was the commitment of the nine dentists: Bill Nichols, Nigel Adams, Roy Dookun, Doris Canning, Malcolm Howat, Joan Davidson, Phil Dixon, Mike Atkinson and Rob Wain. The essential roles of study coordinator, secretary, group convenor and group librarian assumed by Dr Adams, Dr Davidson, Dr Howat and Dr Nichols respectively. Drs Adams and Wassell presented initial trial results at IADR, Seattle 1999 and Drs Nichols and Wassell presented further follow-up at the British Prosthodontic Conference, London 1999. The group is grateful to Mr Michael Adair, of David Bird Dental Ceramics, who made all of the splints.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wassell, R., Adams, N. & Kelly, P. Treatment of temporomandibular disorders by stabilising splints in general dental practice: results after initial treatment. Br Dent J 197, 35–41 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4811420

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4811420

This article is cited by

-

Quantitative and qualitative condylar changes following stabilization splint therapy in patients with temporomandibular joint disorders

Clinical Oral Investigations (2023)

-

Centric relation and increasing the occlusal vertical dimension: concepts and clinical techniques - part two

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

Efficacy of Appliance Therapy on Temporomandibular Disorder Related Facial Pain and Mandibular Mobility: A Randomized Controlled Study

The Journal of Indian Prosthodontic Society (2014)

-

Retrospective examination of the healthcare 'journey' of chronic orofacial pain patients referred to oral and maxillofacial surgery

British Dental Journal (2013)

-

'Management is a black art' – professional ideologies with respect to temporomandibular disorders

British Dental Journal (2007)