Abstract

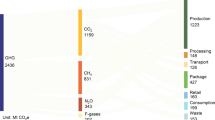

Rapid urbanization and population growth have increased the need for grain transportation in China, as more grain is being consumed and croplands have been moved away from cities. Increased grain transportation has, in turn, led to higher energy consumption and carbon emissions. Here we undertook a model-based approach to estimate the carbon emissions associated with grain transportation in the country between 1990 and 2015. We found that emissions more than tripled, from 5.68 million tons of CO2 emission equivalent in 1990 to 17.69 million tons in 2015. Grain production displacement contributed more than 60% of the increase in carbon emissions associated with grain transport over the study period, whereas changes in grain consumption and population growth contributed 31.7% and 16.6%, respectively. Infrastructure development, such as newly built highways and railways in western China, helped offset 0.54 million tons of CO2 emission equivalent from grain transport. These findings shed light on the life cycle environmental impact within food supply chains.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All the data used in this study are publicly available; for descriptions of the source data, see Methods and Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The custom code and algorithm used for this study are available in Methods and Supplementary Information.

References

Meyfroidt, P., Lambin, E. F., Erb, K. H. & Hertel, T. W. Globalization of land use: distant drivers of land change and geographic displacement of land use. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 5, 438–444 (2013).

van Vliet, J., Eitelberg, D. A. & Verburg, P. H. A global analysis of land take in cropland areas and production displacement from urbanization. Glob. Environ. Change 43, 107–115 (2017).

Garnett, T. Where are the best opportunities for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the food system (including the food chain)? Food Policy 36, S23–S32 (2011).

Clark, M. A. et al. Global food system emissions could preclude achieving the 1.5° and 2°C climate change targets. Science 370, 705–708 (2020).

Hong, C. et al. Global and regional drivers of land-use emissions in 1961–2017. Nature 589, 554–561 (2021).

Carlson, K. M. et al. Greenhouse gas emissions intensity of global croplands. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 63–68 (2017).

Crippa, M. et al. Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nat. Food 2, 198–209 (2021).

Nelson, R. G. et al. Energy use and carbon dioxide emissions from cropland production in the United States, 1990–2004. J. Environ. Qual. 38, 418–425 (2009).

Tukker, A. & Jansen, B. Environmental impacts of products: a detailed review of studies. J. Ind. Ecol. 10, 159–182 (2006).

Xu, X. & Lan, Y. Spatial and temporal patterns of carbon footprints of grain crops in China. J. Clean. Prod. 146, 218–227 (2017).

Linquist, B., Van Groenigen, K. J., Adviento‐Borbe, M. A., Pittelkow, C. & Van Kessel, C. An agronomic assessment of greenhouse gas emissions from major cereal crops. Glob. Change Biol. 18, 194–209 (2012).

Weber, C. L. & Matthews, H. S. Food-miles and the relative climate impacts of food choices in the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 3508–3513 (2008).

Wakeland, W., Cholette, S. & Venkat, K. Food transportation issues and reducing carbon footprint. in Green Technologies in Food Production and Processing (eds Boye, J. & Arcand Y.) pp. 211–236 (Springer, 2012).

Li, M. et al. Global food-miles account for nearly 20% of total food-systems emissions. Nat. Food 3, 445–453 (2022).

Cole, C. V. et al. Global estimates of potential mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions by agriculture. Nutr. Cycling Agroecosyst. 49, 221–228 (1997).

Saunders, C. & Barber, A. Carbon footprints, life cycle analysis, food miles: global trade trends and market issues. Polit. Sci. 60, 73–88 (2008).

Andersson, K., Ohlsson, T. & Olsson, P. Life cycle assessment (LCA) of food products and production systems. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 5, 134–138 (1994).

Vidergar, P., Perc, M. & Lukman, R. K. A survey of the life cycle assessment of food supply chains. J. Clean. Prod. 286, 125506 (2021).

National Bureau of Statistics of China. China Statistical Yearbook 2020 (China Statistics Press, 2020).

Xu, M., He, C., Liu, Z. & Dou, Y. How did urban land expand in China between 1992 and 2015? A multi-scale landscape analysis. PLoS ONE 11, e0154839 (2016).

Wang, L. et al. China’s urban expansion from 1990 to 2010 determined with satellite remote sensing. Chin. Sci. Bull. 57, 2802–2812 (2012).

Yang, B. et al. Impact of cropland displacement on the potential crop production in China: a multi-scale analysis. Reg. Environ. Change 20, 1–13. (2020).

Liu, J. et al. Spatiotemporal characteristics, patterns, and causes of land-use changes in China since the late 1980s. J. Geogr. Sci. 24, 195–210 (2014).

Liu, L., Xu, X., Liu, J., Chen, X. & Ning, J. Impact of farmland changes on production potential in China during 1990–2010. J. Geogr. Sci. 25, 19–34 (2015).

Wang, J., Zhang, Z. & Liu, Y. Spatial shifts in grain production increases in China and implications for food security. Land Use Policy 74, 204–213 (2018).

Yin, F., Sun, Z., You, L. & Müller, D. Increasing concentration of major crops in China from 1980 to 2011. J. Land Use Sci. 13, 480–493 (2018).

Dalin, C., Qiu, H., Hanasaki, N., Mauzerall, D. L. & Rodriguez-Iturbe, I. Balancing water resource conservation and food security in China. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 4588–4593 (2015).

Wang, W. W., Zhang, M. & Zhou, M. Using LMDI method to analyze transport sector CO2 emissions in China. Energy 36, 5909–5915 (2011).

Chen, X., Shuai, C., Wu, Y. & Zhang, Y. Analysis on the carbon emission peaks of China’s industrial, building, transport, and agricultural sectors. Sci. Total Environ. 709, 135768 (2020).

Zuo, C., Birkin, M., Clarke, G., McEvoy, F. & Bloodworth, A. Modelling the transportation of primary aggregates in England and Wales: exploring initiatives to reduce CO2 emissions. Land Use Policy 34, 112–124 (2013).

Zuo, C., Birkin, M., Clarke, G., McEvoy, F. & Bloodworth, A. Reducing carbon emissions related to the transportation of aggregates: is road or rail the solution? Transport. Res. Part A 117, 26–38 (2018).

Cheng, W. M. et al. Spatial-temporal distribution of cropland in China based on geomorphologic regionalization during 1990–2015. Acta Geogr. Sin. 73, 1613–1629 (2018).

Anselin, L. Local indicators of spatial association—LISA. Geogr. Anal. 27, 93–115 (1995).

Kuang, W. et al. Cropland redistribution to marginal lands undermines environmental sustainability. Natl Sci. Rev. 9, nwab091 (2022).

Aubert, C. Food security and consumption patterns in China: the grain problem. Chin. Perspect. 2008, 5–23 (2008).

Zhou, Z. Y., Tian, W. M. & Malcolm, B. Supply and demand estimates for feed grains in China. Agric. Econ. 39, 111–122 (2008).

Mallapaty, S. How China could be carbon neutral by mid-century. Nature 586, 482–484. (2020).

Hou, L. Nation to set obligatory carbon goals. China Daily http://english.www.gov.cn/statecouncil/ministries/202010/29/content_WS5f9a019dc6d0f7257693e947.html (2020).

Ke, X. et al. Direct and indirect loss of natural habitat due to built-up area expansion: a model-based analysis for the city of Wuhan, China. Land Use Policy 74, 231–239 (2018).

Ke, X., Zhou, Q., Zuo, C., Tang, L. & Turner, A. Spatial impact of cropland supplement policy on regional ecosystem services under urban expansion circumstance: a case study of Hubei Province, China. J. Land Use Sci. 15, 673–689 (2020).

He, P., Baiocchi, G., Hubacek, K., Feng, K. & Yu, Y. The environmental impacts of rapidly changing diets and their nutritional quality in China. Nat. Sustain. 1, 122–127 (2018).

Xiong, X. et al. Urban dietary changes and linked carbon footprint in China: a case study of Beijing. J. Environ. Manag. 255, 109877 (2020).

Smith, A, et al. The validity of food miles as an indicator of sustainable development: final report. DEFRA report ED50254. DEFRA http://archive.defra.gov.uk/evidence/economics/foodfarm/reports/documents/foodmile.pdf (2005).

Engelhaupt, E. Do food miles matter? Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 3482 (2008).

Webb, J., Williams, A. G., Hope, E., Evans, D. & Moorhouse, E. Do foods imported into the UK have a greater environmental impact than the same foods produced within the UK? Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 18, 1325–1343 (2013).

Foster, C., Guében, C., Holmes, M., Wiltshire, J. & Wynn, S. The environmental effects of seasonal food purchase: a raspberry case study. J. Clean. Prod. 73, 269–274 (2014).

Leontief, W. & Strout, A. Multiregional input-output analysis. in Structural Interdependence and Economic Development (eds Barna, T. et al.) pp. 119–150 (Palgrave Macmillan, 1963).

Reed, P., Minsker, B. & Goldberg, D. E. Designing a competent simple genetic algorithm for search and optimisation. Water Resour. Res. 36, 3757–3761 (2000).

Dalin, C., Hanasaki, N., Qiu, H., Mauzerall, D. L. & Rodriguez-Iturbe, I. Water resources transfers through Chinese interprovincial and foreign food trade. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 9774–9779 (2014).

Samuelson, P. A. Spatial price equilibrium and linear programming. Am. Econ. Rev. 42, 283–303 (1952).

Ricci, L. A. Economic geography and comparative advantage: agglomeration versus specialisation. Eur. Econ. Rev. 43, 357–377 (1999).

Wilson, A. G. A family of spatial interaction models, and associated developments. Environ. Plan. A 3, 1–32 (1971).

Clarke, M. & Birkin, M. Spatial interaction models: from numerical experiments to commercial applications. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 11, 713–729 (2018).

Chen, Y., Yang, Y. & Zhou, L. Discussion on selection of grain logistic modes in China. Railw. Freight Transp. 2014, 12–17 (2014).

2015 Government GHG Conversion Factors for Company Reporting: Methodology Paper for Emission Factors Final Report, DECC, London. Department of Energy and Climate Change https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/507942/Emission_Factor_Methodology_Paper_-_2015.pdf (2015).

Fotheringham, A. S. & O’Kelly, M. E. Spatial Interaction Models: Formulations and Applications (Kluwer Academic, 1989).

Griffith, D. A. Spatial structure and spatial interaction: 25 years later. Rev. Reg. Stud. 37, 28–38. (2007).

China dimensions data collection: China county-level data on population (census) and agriculture, keyed to 1:1M GIS map. Center for International Earth Science Information Network https://doi.org/10.7927/H43N21B3 (1997).

China county map with 2000–2010 population census data. Harvard Dataverse https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/VKGEBX (2020).

Global roads open access data set, version 1 (gROADSv1). Center for International Earth Science Information Network https://doi.org/10.7927/H4VD6WCT (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (no.2662020GGPY002) and the Later Stage Program of Philosophy and Social Science Research by Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (no. 21JHQ019) (C.Z.), and the Key Program of Philosophy and Social Science Research by Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (no. 20JZD015) (X.K.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.Z. and X.K. conceptualized and designed the study. C.Z. and L.T. collected the original data. C.Z. developed the model framework and compiled the figures. C.Z. and C.W. interpreted the data and analysed the results. C.Z. drafted the manuscript, and C.W., G.C., L.Y. and A.T. reviewed the manuscript and contributed to the revisions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Food thanks Chenyang Shuai, Qiangyi Yu and Bohan Yang for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1

Changes of Mean Centres of Cropland and Population at National Level, Chinese mainland, 1990–2015.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Grain Supply and Consumption 1990–2015.

a) Grain supply by origin 1990–2015; b) Grain consumption by use 1990–2015.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Spatial Distribution of Grain Production and Consumption in 1990 and 2015.

a) Change of population by county 1990–2015; b) Change of cropland area by county 1990–2015; Grain output of each prefecture in c) 1990 and d) in 2015; Grain consumption by prefecture in e) 1990 and f) in 2015.

Extended Data Fig. 4

Modelling Framework for Estimating Carbon Emission of Grain Transport.

Extended Data Fig. 5

Illustration of Modal Choice and Transport Cost Model for Grain Transport.

Extended Data Fig. 6

Transport flows of grain in China at the provincial level, 1990–2015.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Model calibrating, sensitivity analysis, Supplementary Figs. 1–3 and Table 1.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig./Table 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig./Table 6

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zuo, C., Wen, C., Clarke, G. et al. Cropland displacement contributed 60% of the increase in carbon emissions of grain transport in China over 1990–2015. Nat Food 4, 223–235 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-023-00708-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-023-00708-x

This article is cited by

-

Agricultural management practices in China enhance nitrogen sustainability and benefit human health

Nature Food (2024)

-

Increased food-miles and transport emissions

Nature Food (2023)

-

Spatial–temporal dynamics of land use carbon emissions and drivers in 20 urban agglomerations in China from 1990 to 2019

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2023)

-

Characteristics of spatial and temporal carbon emissions from different land uses in Shanxi section of the Yellow River, China

Environment, Development and Sustainability (2023)