Abstract

School teachers are in a unique position to recognize suicide-related problems in their students and to appropriately support them; teachers may need high levels of suicide literacy. However, few studies have examined current levels of suicide literacy in teachers. This study aimed to investigate suicide literacy in school teachers. Teachers (n = 857) from 48 Japanese schools (primary and junior-/senior-high) answered a self-administered questionnaire assessing (a) knowledge about suicide, (b) intention to ask about students’ suicidal thoughts/plans, and (c) attitudes towards talking to students with mental health problems. The average proportion of correct answers to the knowledge questions (10 items) was 55.2%. Over half of the teachers knew that suicide is a leading cause of death in adolescents (55.0%), and that asking about suicidality is needed (56.2%). Half of the teachers intended to ask students about their suicidal thoughts (50.2%) and fewer intended to ask about experiences of planning suicide (38.8%). Most of the teachers (90.4%) agreed with the idea that talking to students with mental health problems was a teacher’s responsibility. Intention to ask about students’ suicidal thoughts/plans were higher in teachers in their 20s (vs. 40s–60s) and working at junior-/senior-high schools (vs. primary schools). Suicide literacy in Japanese school teachers was observed to be limited. However, teachers felt responsibility for helping students with mental health problems. The development and implementation of education programs may help improve teachers’ suicide literacy, which, in turn, could encourage effective helping behaviors of teachers for students struggling with suicidality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Suicide is a leading cause of death in adolescents1 and can be closely linked to mental health problems2,3,4, which start to sharply increase in prevalence during this important and vulnerable period5. However, the majority of adolescents are likely to be reluctant to disclose their intention to die by suicide3,4 and to seek help for their mental health problems6. Considering that adolescents spend a majority of their time in schools, school teachers are expected to play a gatekeeping role for adolescent suicide, that is, recognizing adolescents’ mental health problems including suicidality, and supporting help-seeking behaviors7,8. To play this role, teachers need to have sufficient knowledge about and more understanding attitudes towards suicide and mental health problems/illnesses.

Knowledge about and attitudes towards mental health/illnesses are defined as mental health literacy (MHL)9, and this definition of MHL has been adapted to suicide (hereafter, suicide literacy)10. MHL comprises several components, including the ability to recognize specific disorders, knowledge of risk factors and causes, and having attitudes that promote recognition and appropriate help-seeking9,11. Based on these components of MHL, the following components of suicide literacy have been evaluated: knowledge (e.g., warning signs, risk factors, prevention): confidence (e.g., in asking about suicidality, in providing help): and attitudes (e.g., beliefs in whether suicide is preventable, and in whether suicide risk should be directly asked about)7. Teachers with high suicide literacy as well as MHL may be able to appropriately recognize warning signs of suicide and mental health problems in students, which may enable these students to receive early and appropriate care12,13,14, although the relationship between knowledge about suicide and how it translates to behavioral change remains unclear7.

Thus far, a number of studies have examined MHL in teachers15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29; these studies have observed that the majority of teachers had limited knowledge about15,22,23,26,28 and recognition of15,17,25,27 mental illnesses, and low confidence15,21 in helping students with mental health problems. Several studies have examined suicide literacy in teachers30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37; these studies have also observed that the majority of teachers had limited knowledge about suicide30,31,32,33,34,36,37 and low confidence in helping students with suicidality35. However, most of the studies about suicide literacy in teachers were conducted nearly/over 15 years ago30,31,32,33,34, conducted primarily in North America32,33,35 and Australia30,31,34, and/or did not investigate youth-relevant suicide literacy but suicide literacy in general30,32,36,37. Also, these studies only reported aggregate scores of overall/subcategories (e.g., risk factors, warning signs) of suicide literacy without indicating whether the items, which covered diverse topics (e.g., risk factors/warning signs consisted of mental illnesses, lack of social support, and past experience of suicidal attempts), should be summarized into a single construct (e.g., by factor analysis)30,31,32,37. Importantly, without detailed information about the questions and the responses to them, the specific knowledge that the teachers lacked and which need to be taught are not known. According to a recent systematic review of suicide gatekeeper training programs7, there have been few programs designed specifically for teachers (i.e., the majority of the programs were developed for suicide prevention in general, such as the Question, Persuade, Refer program38). Future suicide literacy programs for teachers need to be designed with the awareness of youth-specific risks and also to equip teachers with the knowledge and skills to deliver interventions that are effective in youth7. Research efforts need to identify the most important points of knowledge that are effective in causing the desired changes in suicide literacy/teacher thinking and behavior, and optimize the delivery of that knowledge. To develop effective programs, assessing current levels of specific knowledge about adolescent suicide among teachers is a reasonable first step, and further research in more diverse populations and communities worldwide is needed.

In Japan, suicide is the leading cause of death in adolescents39, and the suicide rate increased from 3.8 per 100,000 in 1990 to 9.9 per 100,000 in 2019 for 15–19 year olds40, much higher than average and median global suicide rates (6.1 and 4.2 per 100,000 in 2019, respectively41), a situation which requires more systemic attention. Japan does not have a system of general practitioners42 and there are few full-time school counselors/psychologists43 or other easy-to-reach professionals from whom adolescents may access mental health services (as available in other countries44). In this situation, teachers in Japan have the potential to play important roles in helping students with suicidality and other mental health problems; improving teacher suicide literacy and MHL may be an important step in empowering them to help at-risk adolescents.

Understanding the relationship between the different components of suicide literacy is also important. Previous studies have only examined associations between “knowledge” and “attitudes” (stigma towards people with suicidality)45,46,47. Considering that the “intention” (included in the “attitudes” component) to do something predicts actual future behaviors14,48, an important next step is to investigate the relationship between “knowledge” and the intention to directly ask about suicide risk; asking can be crucial in suicide prevention3,4,38,49,50,51. One open question is whether having more knowledge and awareness leads to higher intention to ask, or whether having the intention to inquire about suicide reflects more motivation to prevent it, leading an individual to seek out knowledge.

The aim of the current study is to assess current levels of specific knowledge about adolescent suicide and intention to ask about students’ suicidal thoughts/plans in Japanese teachers. These knowledge and intention are needed to develop effective gatekeeper training programs for teachers to recognize suicidality in their students and appropriately support them. Additionally, we examined associations between knowledge about adolescent suicide and intention to ask about students’ suicidal thoughts/plans while also examining the effects of demographic variables (e.g., age and sex) which have been observed to affect suicide literacy in adult samples (not limited to teachers)45,46,47,52,53,54.

Methods

Procedure and participants

In 2020, the Board of Education of Saitama prefecture (population: 7 million) informed all public schools in their jurisdiction about the current study. The principals of 48 prefectural or municipal schools (20 primary schools, 18 junior high schools, and 10 senior high schools) told the Board that they wanted their schools to participate in the study; in these schools, 58.6% (n = 857) of teachers participated in the current study.

Contents of the questionnaire

Suicide literacy in teachers was assessed using a self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire was drafted by one of the authors (TS) and edited and refined by a team of psychiatrists, psychologists (including JCF), teachers (including SY) and school nurses. The questionnaire was written in Japanese, and comprised the following 4 parts.

Part 1: Demographic variables

Demographic information of teachers was assessed. The information included age, sex, school type (primary school, junior high school, or senior high school), academic degree, previous participation in mental health seminars, and experience of dealing with someone suffering from a mental illness (Table 1).

Part 2: Knowledge about suicide

The second part of the questionnaire comprised 10 questions regarding knowledge about suicide (Table 2), including basic knowledge about the epidemiology, risk factors and care/treatment of suicide, based on vital statistics in Japan39 and previous studies2,3,4,7,49,50,51,55,56. The possible answers to these questions were: “True”, “False”, or “I don’t know”. Correct answers were scored 1 (otherwise scored 0) and the scores were added up. In the present sample, the internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of the questions was 0.63.

Part3: Intention to ask about students’ suicidal thoughts/plans

Teachers were asked to read a case vignette describing a teenage student (Student A) with suicidal thoughts. The vignette was adapted from Jorm et al.12.

The description of the vignette is as follows. “Student A feels that they will never be happy again and believes that their family would be better off without them. They have had feelings of hopelessness and have constantly been thinking of ways to end their life. They have also been up to a rooftop with the intention to jump.”

Having read this vignette, teachers were asked to what extent they agreed with the 5 items (see Table 3) regarding intention to ask students who were in a similar situation to student A about their suicidal thoughts/plans. There were 4 answer choices, and these choices were scored as follows: “Strongly agree” (4), “Agree” (3), “Disagree” (2), “Strongly disagree” (1). Higher score indicated higher intention. The total score of the 5 items was used for statistical analyses. In the present sample, the internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of the items was 0.92.

Part 4: Attitudes towards talking to students with mental health problems

In the fourth part, teachers were asked the following question: “How confident do you feel in talking to students with mental health problems?” Possible answers to this question were “Fully confident”, “Confident”, “Not very confident”, “Not confident at all”. The teacher was considered to have confidence, when the answer was “Fully confident” or “Confident”. In addition, teachers were asked “What extent do you agree with the idea that talking to students with mental health problems is teachers’ responsibility?” Possible answers to the question were “Strongly agree”, “Agree”, “Disagree” or “Strongly disagree”. The teacher was considered to agree with the idea when the answer was “Strongly agree” or “Agree”.

Statistical analysis

Demographic statistics were compiled and responses to the questionnaires were evaluated. Multilevel regression analyses were conducted to examine whether knowledge about suicide (knowledge) had an effect on intention to ask about students’ suicidal thoughts/plans (intention) in teachers, or vice versa, while also examining effects of demographic variables. All demographic variables shown in Table 1 were included in the models. A random effect of intercept for school was included in the analyses, since the teachers were sampled from 48 different schools. The level of significance was set at alpha = 0.05. The analyses were performed using R version 4.1.3 with the lme4 and lmerTest package.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The aim and contents of the study were explained to participating teachers in writing, and we obtained written informed consent from all the teachers who participated. The study was approved by The University of Tokyo Human Research Ethics Committee (#18–48). This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Demographic variables

Table 1 shows demographic data of participating teachers. More than half of the teachers were in their 20s or 30s (57.2%) and male (56.4%). Completion of a Bachelor’s degree was the highest education level for most of the teachers (83.0%). One fifth of the teachers (20.2%) previously participated in a mental health seminar once or more. More than half of the teachers previously had experiences of dealing with someone suffering from a mental illness (59.5%).

Knowledge about suicide

Table 2 shows the proportion of correct answers to the knowledge questions about suicide. The average proportion of correct answers was 55.2% (standard deviation = 21.9%). Regarding specific questions, seven out of ten items had low proportions (around or below half) of correct answers: for example, the fact that suicide is the leading cause of death among older teens (aged 15–19) in Japan (55.0%); the need to ask about suicidal ideation (56.2%) and specific suicide plans (37.6%); the fact that a previous suicide attempt is a significant risk factor for suicide (15.4%); that the focus of suicide prevention efforts does not have to be primarily on students who repeatedly self-harm (56.1%), and who are currently receiving treatment by mental health specialists (58.0%).

Intention to ask about students’ suicidal thoughts/plans

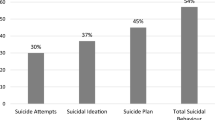

Table 3 shows intention of the teachers to ask students who are similar to Student A in the vignette about their suicidal thoughts/plans. Regarding suicidal thoughts, half of the teachers disagreed or strongly disagreed to ask students if they did not wish to live (47.1%) or wished to die (49.8%). Regarding suicidal plans, a majority of teachers disagreed or strongly disagreed to ask students about their experiences of thinking about how to die by suicide (61.2%) and of preparing for suicide (57.7%).

Attitudes towards talking to students with mental health problems

Most of the teachers (90.4%) agreed with the idea that talking to students with mental health problems was a teachers’ responsibility. However, less than half of the teachers (43.6%) answered that they had the confidence in talking to students with such problems.

Association between knowledge about suicide and intention to ask about students’ suicidal thoughts/plans

Table 4 shows the results of the multilevel regression analyses examining whether knowledge had an effect on intention in teachers, or vice versa, in addition to examining the effects of demographic variables on knowledge and intention. Teachers with higher levels of intention had significantly higher knowledge (unstandardized coefficient (B) = 0.15, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.11–0.18), while no demographic variables had significant effects on knowledge. In the analysis where intention was modeled as the outcome, it was observed that teachers with higher knowledge had significantly higher levels of intention (B = 0.57, 95% CI 0.44–0.71). Also, teachers in their 40s (B = − 1.02, 95% CI − 1.98 to − 0.05), 50s (B = − 1.98, 95% CI − 2.88 to − 1.08) and 60s (B = − 1.58, 95% CI − 2.64 to − 0.52) had lower intention compared to teachers in 20s. Intention was higher among teachers working at junior-high schools (B = 0.79, 95% CI 0.02–1.55) and senior-high schools (B = 1.20, 95% CI 0.36–2.03) compared to teachers working at primary schools. There were no significant effects of sex, previous experiences of participating mental health seminar, and previous experience of dealing with someone suffering from a mental illness on intention.

Discussion

The current study investigated suicide literacy in Japanese school teachers. The level of the literacy in Japanese teachers may be limited; proportions of the correct answers were around 50% or lower to most of the suicide knowledge questions, and around half of the teachers would not ask students with suicidality about their suicidal thoughts/plans. On the other hand, most of the teachers regarded talking to students with mental health problems as a part of their responsibility, although their confidence in talking about such problems with the students is low. Considered together, improving suicide literacy in teachers may be a first step for them to actually help students with suicidality.

Regarding the specific knowledge, approximately half of the teachers did not know the fact that suicide is the leading cause of death among older teens (aged 15–19) in Japan39, which may suggest teachers’ low awareness of or familiarity with suicide-related problems in adolescents. Considering that one of major risk factors is mental health problems2,3,4, which are prevalent during adolescence5, a large number of students are potentially at risk of suicide. A recent meta-analysis reported that the 12-month prevalence of suicidal ideation was 14.2%, and that of suicide attempts was 4.5% in adolescents worldwide57. Knowledge of these facts may help teachers perceive suicide-related problems as personally relevant, which, in turn, may lead to them engaging in preventive behaviors58. This knowledge could be provided to teachers through suicide literacy training programs.

Also, approximately half of the teachers thought that asking about suicidal ideation could lead to a suicide attempt. These types of effects have not been seen in previous studies49,50,51. Asking students about the ideation may be needed for teachers to proactively recognize and intervene in cases of student suicidality, since the majority (71–76%) of those who die by suicide tend not to disclose their intention to die by suicide3,4.

Furthermore, around half of the teachers did not know that the focus of suicide prevention should also be on students who do not clearly show mental health related problems (i.e., repeating self-harm, receiving treatment by mental health specialists); although self-harm and mental illnesses are risk factors of suicide2,3,4, the majority (79%) of those who die by suicide appear not to experience self-harm4 and are not (70–72%) receiving treatments for mental illnesses3,4. Focusing only on these factors may lead to overlooking many students with suicide risk. Teachers need to know these facts, and need to talk to students about any concerns such as mental health problems when students seem to have these concerns. Teachers equipped with such knowledge may be willing to talk to students about their concerns, considering that most of the teachers felt responsibility for helping students with mental health problems.

Around half of the teachers indicated that they would not ask students with suicidality about their suicidal thoughts/plans. This number is concerning, considering that asking about suicide is a crucial part of suicide prevention3,4,38,49,50,51. Increasing this intent may be important to encourage teachers to take action, as attitudes (including the intention of doing something) predict future actual behaviors14,48. In our models, we observed that knowledge had a significant effect on intention, and intention also had a significant effect on knowledge. It may be possible both that providing teachers with knowledge about adolescent suicide may lead to increased intention to ask about students’ suicidal thoughts/plans, and that improving intention may motivate teachers, leading to investing more effort to gain knowledge. Due to the cross-sectional nature of this design, we cannot evaluate the directionality of these effects. Still, our study provides preliminary evidence about the associations between knowledge and intention, and suggests that bidirectional effects exist; knowledge and intention are likely to be linked and both important components of literacy. Future research will need to look closer at this relationship.

Regarding the effects of demographic variables, junior- and senior-high school teachers expressed higher levels of intention compared to primary school teachers. In Japan, the age of students in junior- and senior-high schools ranges from 12–18, where the number of suicide death sharply increases39; suicide related issues may draw more attention in teachers in these schools compared to teachers in primary schools. Teachers’ age, sex, and education level had no significant effects on their knowledge. None of these factors were observed to have significant effects in one previous study investigating the general population53, but other studies have observed that all52 or some45,46,47 of these factors had significant effects; younger age45,46,47,52, female sex52, and higher education level46,47,52 had positive effects on knowledge. Further studies are needed to clearly understand the effects of these factors. Regarding education level, a limited range in teachers (most teachers had Bachelor’s degrees) may have resulted in its non-significant effect; previous studies observing a significant effect of education level in the general population included more varied education levels (e.g., high school or less)46,47,52. Previous participation in mental health seminar did not have a significant effect on knowledge or intention. Thus far, a number of MHL programs for teachers have been developed59; however, only a some of the programs address suicide60,61,62,63,64,65,66, and few suicide prevention trainings have been developed specifically for teachers7. More suicide literacy programs for teachers need to be developed and implemented.

Limitations

The current study has several limitations. First, participants were school teachers from a single prefecture in Japan. Caution may be needed when generalizing these results to other populations. Second, the participation rate was not high (58.6%), although the rate is not lower than our previous study (53.3%) investigating MHL in high school teachers from another prefecture15. Suicide literacy in teachers who decided to participate might differ from the literacy in those who did not. Third, the questionnaire used in the current study was newly developed and tailored to assess suicide literacy in teachers through discussion with specialists in mental health and adolescents such as psychiatrists, psychologists, teachers and school nurses.

Conclusions

Suicide literacy in the Japanese school teachers (from primary, junior-/senior-high schools) may be limited; they had insufficient knowledge about adolescent suicide and low intention to ask students with suicidality about their suicidal thoughts/plans. However, most of the teachers regarded talking to their students with mental health problems as a part of their responsibility, suggesting that they may be willing to act if properly prepared. Programs which effectively provide teachers with suicide literacy may help teachers notice students with suicidality and appropriately support them. Efforts should be made to incorporate these suicide literacy programs in teacher training, not only for in-service teachers but also for pre-service teachers at the university level. To do so, help will be needed at the level of educational policy and governance, by urging educational boards and ministries to take action.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to data protection and privacy regulations of the Saitama Prefectural Board of Education. They may be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- MHL:

-

Mental health literacy

References

World Health Organization. Suicide worldwide in 2019. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1350975/retrieve. Accessed 12 March 2023.

Bridge, J. A., Goldstein, T. R. & Brent, D. A. Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 47(3–4), 372–394 (2006).

Karch, D. L., Logan, J., McDaniel, D. D., Floyd, C. F. & Vagi, K. J. Precipitating circumstances of suicide among youth aged 10–17 years by sex: Data from the National Violent Death Reporting System, 16 states, 2005–2008. J. Adolesc. Health 53(Suppl 1), S51–S53 (2013).

Annor, F. B. et al. Characteristics of and precipitating circumstances surrounding suicide among persons aged 10–17 years—Utah, 2011–2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 67(11), 329–332 (2018).

Kessler, R. C. et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry 6(3), 168–176 (2007).

Rickwood, D., Deane, F. P., Wilson, C. J. & Ciarrochi, J. Young people’s help-seeking for mental health problems. Aust. e-J. Adv. Ment. Health 4(3), 218–251 (2005).

Torok, M., Calear, A. L., Smart, A., Nicolopoulos, A. & Wong, Q. Preventing adolescent suicide: A systematic review of the effectiveness and change mechanisms of suicide prevention gatekeeping training programs for teachers and parents. J. Adolesc. 73, 100–112 (2019).

Johnson, C., Eva, A. L., Johnson, L. & Walker, B. Don’t turn away: Empowering teachers to support students’ mental health. Clear. House 84(1), 9–14 (2011).

Jorm, A. F. et al. “Mental health literacy”: A survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Med. J. Aust. 166(4), 182–186 (1997).

Calear, A. L., Batterham, P. J., Trias, A. & Christensen, H. The literacy of suicide scale. Crisis 43(5), 385–390 (2022).

Jorm, A. F. Mental health literacy: Empowering the community to take action for better mental health. Am. Psychol. 67(3), 231–243 (2012).

Jorm, A. F., Blewitt, K. A., Griffiths, K. M., Kitchener, B. A. & Parslow, R. A. Mental health first aid responses of the public: Results from an Australian national survey. BMC Psychiatry 5, 9 (2005).

Rossetto, A., Jorm, A. F. & Reavley, N. J. Examining predictors of help giving toward people with a mental illness: Results from a national survey of Australian adults. SAGE Open 4, 2158244014537502 (2014).

Rossetto, A., Jorm, A. F. & Reavley, N. J. Predictors of adults’ helping intentions and behaviours towards a person with a mental illness: A six-month follow-up study. Psychiatry Res. 240, 170–176 (2016).

Yamaguchi, S., Foo, J. C., Kitagawa, Y., Togo, F. & Sasaki, T. A survey of mental health literacy in Japanese high school teachers. BMC Psychiatry. 21(1), 478 (2021).

Masillo, A. et al. Evaluation of secondary school teachers’ knowledge about psychosis: A contribution to early detection. Early Interv. Psychiatry 6(1), 76–82 (2012).

Monducci, E. et al. Secondary school teachers and mental health competence: Italy-United Kingdom comparison. Early Interv. Psychiatry 12(3), 456–463 (2018).

Collins, A. & Holmshaw, J. Early detection: A survey of secondary school teachers’ knowledge about psychosis. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2(2), 90–97 (2008).

Langeveld, J. et al. Teachers’ awareness for psychotic symptoms in secondary school: The effects of an early detection programme and information campaign. Early Interv. Psychiatry 5(2), 115–121 (2011).

Herbert, J. D., Crittenden, K. & Dalrymple, K. L. Knowledge of social anxiety disorder relative to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among educational professionals. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 33(2), 366–372 (2004).

Reinke, W. M., Stormont, M., Herman, K. C., Puri, R. & Goel, N. Supporting children’s mental health in schools: Teacher perceptions of needs, roles, and barriers. Sch. Psychol. Q. 26(1), 1–13 (2011).

Walter, H. J., Gouze, K. & Lim, K. G. Teachers’ beliefs about mental health needs in inner city elementary schools. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 45(1), 61–68 (2006).

Kerebih, H., Abrha, H., Frank, R. & Abera, M. Perception of primary school teachers to school children’s mental health problems in Southwest Ethiopia. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 30(1), 20160089 (2016).

Aghukwa, N. C. Secondary school teachers’ attitude to mental illness in Ogun State, Nigeria. Afr. J. Psychiatry 12(1), 59–63 (2009).

Aluh, D. O., Dim, O. F. & Anene-Okeke, C. G. Mental health literacy among Nigerian teachers. Asia Pac. Psychiatry 10, e12329 (2018).

Bella, T., Omigbodun, O. & Atilola, O. Towards school mental health in Nigeria: Baseline knowledge and attitudes of elementary school teachers. Adv. Sch. Ment. Health Promot. 4(3), 55–62 (2011).

Kurumatani, T. et al. Teachers’ knowledge, beliefs and attitudes concerning schizophrenia: A cross-cultural approach in Japan and Taiwan. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 39(5), 402–409 (2004).

Ngwenya, T. Z., Huang, N., Wang, I. A. & Chen, C. Y. Urban-rural differences in depression literacy among high school teachers in the Kingdom of Eswatini. J. Sch. Health 92(6), 561–569 (2022).

Dey, M., Marti, L. & Jorm, A. F. Teachers’ experiences with and helping behaviour towards students with mental health problems. Int. Educ. Stud. 15(5), 118–131 (2022).

Leane, W. & Shute, R. Youth suicide: The knowledge and attitudes of Australian teachers and clergy. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 28(2), 165–173 (1998).

Scouller, K. M. & Smith, D. I. Prevention of youth suicide: How well informed are the potential gatekeepers of adolescents in distress?. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 32(1), 67–79 (2002).

MacDonald, M. G. Teachers’ knowledge of facts and myths about suicide. Psychol. Rep. 95(6), 651–656 (2004).

Westefeld, J. S., Jenks Kettmann, J. D., Lovmo, C. & Hey, C. High school suicide: Knowledge and opinions of teachers. J. Loss Trauma 12(1), 33–44 (2007).

Crawford, S. & Caltabiano, N. The school professionals’ role in identification of youth at risk of suicide. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 34(2), 28–39 (2009).

Hatton, V. et al. Secondary teachers’ perceptions of their role in suicide prevention and intervention. Sch. Ment. Health 9(1), 97–116 (2016).

de Oliveira, J. M., Calderón, P. V. & Caballero, P. B. “I wish I could have helped him in some way or put the family on notice”: An exploration of teachers’ perceived strengths and deficits in overall knowledge of suicide. J. Loss Trauma 26(3), 260–274 (2020).

Phoa, P. K. A. et al. The Malay Literacy of Suicide Scale: A Rasch model validation and its correlation with mental health literacy among Malaysian parents, caregivers and teachers. Healthcare (Basel) 10(7), 1304 (2022).

QPR Institute. Question. Persuade. Refer. Three steps anyone can learn to help prevent suicide. https://www.qprinstitute.com/. Accessed 3 Nov 2023.

Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare. Overview of monthly vital statistics annual report (approximate numbers) (2022). https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/jinkou/geppo/nengai22/dl/gaikyouR4.pdf. Accessed 2 Dec 2023.

Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare. Number of suicide deaths and suicide mortality rate based on vital statistics (2019). https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/hukushi_kaigo/seikatsuhogo/jisatsu/jinkoudoutai-jisatsusyasu.html. Accessed 3 Nov 2023.

World Health Organization. Suicide rates, crude, among adolescents 15–19 years (2019). https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mental-health/suicide-rates. Accessed 9 Nov 2023.

Hashimoto, H. et al. Cost containment and quality of care in Japan: Is there a trade-off?. Lancet 378, 1174e82 (2011).

Yoshikawa, K., deLeyer-Tiarks, J., Kehle, T. J. & Bray, M. A. Japanese educational reforms and initiatives as they relate to school psychological practice. Int. J. Sch. Educ. Psychol. 7, 83–93 (2019).

Rickwood, D. J., Deane, F. P. & Wilson, C. J. When and how do young people seek professional help for mental health problems?. Med. J. Aust. 187, S35e9 (2007).

Cruwys, T., An, S., Chang, M. X. & Lee, H. Suicide literacy predicts the provision of more appropriate support to people experiencing psychological distress. Psychiatry Res. 264, 96–103 (2018).

Ludwig, J., Dreier, M., Liebherz, S., Harter, M. & von dem Knesebeck, O. Suicide literacy and suicide stigma—Results of a population survey from Germany. J. Ment. Health 31(4), 517–523 (2022).

Nakamura, K., Batterham, P. J., Chen, J. & Calear, A. L. Levels and predictors of suicide stigma and suicide literacy in Japan. Psychiatry Res. Commun. 1(1), 10009 (2021).

Webb, T. L. & Sheeran, P. Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychol. Bull. 132(2), 249–268 (2006).

Coppersmith, D. D. L. et al. Effect of frequent assessment of suicidal thinking on its incidence and severity: High-resolution real-time monitoring study. Br. J. Psychiatry 220(1), 41–43 (2022).

DeCou, C. R. & Schumann, M. E. On the iatrogenic risk of assessing suicidality: A meta-analysis. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 48(5), 531–543 (2018).

Polihronis, C., Cloutier, P., Kaur, J., Skinner, R. & Cappelli, M. What’s the harm in asking? A systematic review and meta-analysis on the risks of asking about suicide-related behaviors and self-harm with quality appraisal. Arch. Suicide Res. 26(2), 325–347 (2022).

Batterham, P. J., Calear, A. L. & Christensen, H. Correlates of suicide stigma and suicide literacy in the community. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 43(4), 406–417 (2013).

Money, T. T. & Batterham, P. J. Sociocultural factors associated with attitudes toward suicide in Australia. Death Stud. 45(3), 219–225 (2021).

Oliffe, J. L. et al. Men’s depression and suicide literacy: A nationally representative Canadian survey. J. Ment. Health 25(6), 520–526 (2016).

Paykel, E. S., Myers, J. K., Lindenthal, J. J. & Tanner, J. Suicidal feelings in the general population: A prevalence study. Br. J. Psychiatry 124, 460–469 (1974).

Noh, D. Relational-level factors influencing suicidal behaviors among Korean adolescents. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 51(6), 634–641 (2019).

Lim, K. S. et al. Global lifetime and 12-Month Prevalence of suicidal behavior, deliberate self-harm and non-suicidal self-injury in children and adolescents between 1989 and 2018: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16(22), 4581 (2019).

Kwasnicka, D., Dombrowski, S. U., White, M. & Sniehotta, F. Theoretical explanations for maintenance of behaviour change: A systematic review of behaviour theories. Health Psychol. Rev. 10(3), 277–296 (2016).

Yamaguchi, S. et al. Mental health literacy programs for school teachers: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Early Interv. Psychiatry 14(1), 14–25 (2020).

Jorm, A. F., Kitchener, B. A., Sawyer, M. G., Scales, H. & Cvetkovski, S. Mental health first aid training for high school teachers: A cluster randomized trial. BMC Psychiatry 10, 51 (2010).

Kidger, J. et al. A pilot cluster randomised controlled trial of a support and training intervention to improve the mental health of secondary school teachers and students—The WISE (Wellbeing in Secondary Education) study. BMC Public Health 16(1), 1060 (2016).

Kutcher, S. et al. Improving Malawian teachers’ mental health knowledge and attitudes: An integrated school mental health literacy approach. Glob. Ment. Health. 2, e1 (2015).

Kutcher, S. et al. A school mental health literacy curriculum resource training approach: Effects on Tanzanian teachers’ mental health knowledge, stigma and help-seeking efficacy. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 10, 50 (2016).

Kutcher, S., Wei, Y., McLuckie, A. & Bullock, L. Educator mental health literacy: A programme evaluation of the teacher training education on the mental health and high school curriculum guide. Adv. Sch. Ment. Health Promot. 6(2), 83–93 (2013).

Wei, Y., Kutcher, S., Hines, H. & MacHay, A. Successfully embedding mental health literacy into Canadian classroom curriculum by building on existing educator competencies and school structures. Lit. Inf. Comput. Educ. J. 5(3), 1649–1654 (2014).

Coppens, E. et al. Effectiveness of community facilitator training in improving knowledge, attitudes, and confidence in relation to depression and suicidal behavior: Results of the OSPI-Europe intervention in four European countries. J. Affect. Disord. 165, 142–150 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors are profoundly grateful to the Saitama Prefectural Board of Education for their collaboration, cooperation, and contributions to the research.

Funding

This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (#18H01009 and #21H00857). The funder had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Y. and J.C.F. drafted the manuscript, with the supervision by T.S.; S.Y. and T.S. developed the questionnaire. S.Y. analyzed the data. T.S. and S.Y. cooperated with the Board of Education to conduct the survey in public schools. T.S. supervised the study process.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamaguchi, S., Foo, J.C. & Sasaki, T. A survey of suicide literacy in Japanese school teachers. Sci Rep 13, 23047 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50339-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50339-2

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.