Abstract

The 10-item Kessler Psychological Distress scale (K10) and its 6-item short-form version (K6) measure psychological distress, particularly anxiety or depressive symptoms. While these questionnaire scales are widely used in various settings and populations, general population normative data are rarely available. To facilitate the interpretation of K10 and K6 scores, we provide normative general population data from seven European countries. We used an online survey to collect K10 data from general population samples in Austria, Italy, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Poland and Spain. We calculated the age- and sex-specific normative values separately for each country. For more specific estimates of K10 and K6 scores for individuals or groups, we also established a multivariable regression model based on socio-demographic and health data. In total, N = 7,087 adults participated in our study (51.6% women; mean age, 49.6 years). The mean K10 score in the total sample was 8.5 points (standard deviation, 7.3) on 0–40 points metric, with mean scores in individual countries ranging from 6.9 (the Netherlands) to 9.9 (Spain). Women showed higher scores than men and younger participants scored higher than older participants. Our study is the first to present normative K10 and K6 data from several European countries using a consistent sampling approach. These reference values will facilitate the interpretation of K10 and K6 scores in clinical research and practice and also highlight the variation in psychological distress levels across countries and groups according to their socio-demographic and health characteristics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Affective and anxiety disorders are the most common psychiatric diagnoses in the general population1,2. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s 2018 Health at a Glance report3 estimates that 25 million people (5.4% of the general population) in the European Union were living with an anxiety disorder and more than 21 million people (4.5% of the general population) were living with depressive disorders, which not only cause individual suffering but also high socio-economic costs3. While these prevalence rates are high, they may still underestimate the true extent of such mental health problems because these are known to be underdiagnosed and can exist for a long time before being detected and treated4. Effective diagnostic strategies are therefore of vital importance, not only for obtaining reliable prevalence estimates but also better referral of individuals to adequate treatment.

Structured diagnostic interviews for diagnosis of mental health disorders, such as the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID)5, or the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI)6 are considered the diagnostic gold standard but take a long time to complete and can only be conducted in a one-on-one setting. In contrast, screening questionnaires targeting mental health disorders offer the benefits of being concise and applicable in a wider research context without the need for direct contact with a mental health professional. Such questionnaires allow a detailed assessment of psychological distress levels and may also help to identify individuals with mental health disorders.

While numerous psychological screening questionnaires are available for specific patient populations and target disorders7,8,9, the 10-item Kessler Psychological Distress scale (K10)10 was developed specifically to assess psychological distress and screen for mental health disorders in the general population. Initially, its unidimensional scale intended to measure “psychological distress”10, whereby depression and anxiety were identified as secondary independent factors in multifactorial models11. Since its development, the K10 scale has been used in a number of large-scale epidemiological studies12,13,14 and in clinical practice15,16, in addition to measuring clinical study outcomes17. The K10 scale and its short-form version, the K6 scale, have shown strong psychometric properties such as good reliability, construct and criterion validity in various populations18,19,20, with some variation across different cultural groups15,21,22 Furthermore, they possess the ability to identify individuals with mental health disorders in different settings with high accuracy12,23,24,25. For screening purposes, thresholds have been established to allow the calculation of the prevalence rates of mental health disorders. While prevalence data are easy to interpret, they come at the disadvantage of reduced information because the actual distribution of the varying levels of distress is lost when thresholds are applied. The use of normative data, such as general population data, is an alternative approach for the interpretation of scale scores that does not require thresholds. The measurement of these normative data for psychological distress using the K10 scale provides detailed information for researchers, health-care professionals, and policymakers about the distress levels in different groups of individuals. These data may help to identify vulnerable populations. Previous studies have collected reference data from large samples of diverse populations13,14,26, but general population normative data are rarely available. Considering the variation in the score distributions and measurement characteristics of the K10 scale15 across countries, country-specific normative data should allow for the valid interpretation of scores.

Therefore, to facilitate the interpretation of K10 (and K6) data from European populations and to investigate the variation in K10 (and K6) scores across countries, our study aimed to establish sex- and age-specific general population normative data from seven European countries (i.e., Austria, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, and Spain).

Methods

Sample

This study used adult general population data from a cross-cultural study in seven European countries27,28,29 to obtain normative values for the K10 scale. We outsourced the panel data collection to a market research institute, SurveyEngine (Berlin, Germany, https://surveyengine.com/), which contacts panel members who have registered voluntarily and agreed to participate in similar studies. The countries were assessed in consecutive projects; therefore, the online surveys were sent out between September 2015 and December 2018. We set quotas for sex and the predefined age groups (18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, and 70 + years) to obtain a raw approximation of the proportion of the general population in these age and sex groups based on United Nations statistics30.

Socio-demographic and health data

The questionnaire included a data form that collected the participants’ basic socio-demographic and health data, including their age, sex, educational level, marital status and living situation. We also asked the participants if they had been hospitalised during the previous 12 months and if they suffer from health conditions. For the latter, we provided a list of major chronic disorders, including mental health disorder, with a binary response format (i.e., no/yes) for each of these conditions.

The K10 and K6 scales

The K10 comprises 10 items exploring the non-specific psychological distress experienced in the last 4 weeks10. In addition, the K6 scale uses the first six items from the K10 scale. Both questionnaire versions can be used to indicate distress in populations or individuals. All items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = ‘none of the time’ to 5 = ‘all of the time’). All items assess the participants’ psychological distress with questions focusing on anxiety and depression, such as, ‘In the last 4 weeks, how often did you feel nervous?’.

A total score can be calculated by adding all item scores, with high scores indicating high levels of distress. Following the original scoring instructions10, the score range for the K10 is 0 to 40 points, while the score range for the K6 short-form is 0–24 points.

Statistical analysis

Sample characteristics are given as means, standard deviations, and absolute and relative frequencies. While the data collection already approximated the age and sex distribution in the individual countries, we applied additional weights using raking to more precisely match the national age and sex distributions30.

We described the weighted normative data for the K10 and K6 scales using means and standard deviations (SDs) and percentiles (10th, 25th, 50th, 75th and 90th) separately for the total sample and country-, age- and sex-specific groups.

To allow for more precise normative values in specific groups of individuals, we also developed a regression model to predict their K10 and K6 scores using the following independent variables: sex, age group, educational level, somatic chronic conditions, mental chronic conditions, and country. All predictors that were statistically significant in the univariate analysis (p < 0.05) were included in the multivariable model, except for mental health, which we excluded from the multivariate analysis to avoid over-adjustment.

To evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of the K10 scale in predicting self-reported mental health disorders (as reported in the initial questionnaire data), we used receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis to calculate the area under the curve (AUC) as a measure of diagnostic accuracy and determined the possible cut-off values separately for each country.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Data is not publicly available, but was provided anonymised by the panel research company SurveyEngine GmbH to the authors. No ethics approval was sought as the study is based on panel data. According to the NHS Health Research Authority and the European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association (EphMRA), panel research does not require ethical approval if ethical guidelines are followed. The survey was distributed via the SurveyEngine GmbH and obtained informed consent by each participant before the study. All data were collected anonymously and identification of the respondents through the authors or anyone else is impossible. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional guides on the care and use of laboratory animals.

Results

Participant characteristics

The survey data from N = 7,087 adult individuals from seven European countries were available for analysis. In the unweighted data, the mean age was 49.6 (SD = 16.1) and women comprised 51.6% of the sample. The weights applied to the data ranged from 0.74 to 1.83 units. In the weighted data, the mean age was 50.0 years (SD = 16.6) and women still comprised 51.6% of the sample. Most participants indicated an educational level of secondary school or vocational training (56.3%). Health conditions were reported by 39.4% of the participants, with arthritis/rheumatism (11.0%), asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (9.5%) and diabetes (9.1%) being the three most frequent conditions. Hospitalisation during the previous 12 months was reported by 15.9% of the participants. The details of the unweighted and weighted sample characteristics for the total sample and individual countries are shown in Table 1.

Normative data for the K10 and K6 scales by country, sex and age

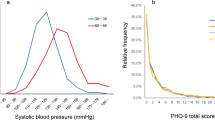

In the weighted total sample, the K10 mean score was 8.5 points (SD = 7.3). The maximum possible score of 40 points was obtained by 0.1% of the participants and the minimum score of 0 points by 9.4% across all countries. The distribution of K10 scores in each country is illustrated in Fig. 1. The mean K10 scores were highest in Spain (9.9 points) and Poland (9.7), followed by France (8.7), Italy (8.4), Germany (8.3), Austria (7.9) and the Netherlands (6.9). Women showed higher K10 mean scores than men across all countries. The largest mean sex differences were found in Germany (+ 2.1 points for women compared to men), Spain (+ 1.9 points for women) and Italy (+ 1.7 points for women).

In all seven countries, the two youngest age groups (18–29 and 30–39 years) had the highest K10 mean scores. The largest age-related differences were found in Germany (+ 3.8 points in participants aged 18–29 vs. > 70 years) and the Netherlands (+ 3.1 points in the 18–29 age group vs. the > 70 age group). The age trends for the K10 scores are shown in Fig. 2.

The detailed normative data for individual countries and sex and age groups for the K10 scale are shown in Table 2. The normative data for the K6 scale are shown in Supplementary Table 2, while the response frequencies for the individual items of the K10 and K6 scale are reported in Supplementary Table 5.

Regression model for estimating K10 and K6 scores

The univariable linear regression analysis showed that the K10 scores were statistically significantly associated with age (pairwise comparison against the reference ‘18–29 years’ for all age groups [p < 0.001] but the ‘30–39 years’ group [p = 0.681]), sex (p < 0.001), chronic somatic health conditions (p < 0.001), chronic mental health conditions (p < 0.001), country (pairwise comparisons against the reference ‘Germany’ were statistically significant for Poland [p < 0.001], the Netherlands [p < 0.001], and Spain [p < 0.001]) and educational level (compulsory school education or less differed statistically significantly from secondary or vocational training [p = 0.005] and university degree [p = 0.002]).

The backward exclusion of predictors in the multivariable linear regression model retained all included variables. For age, all but the ‘30–39 years’ (p = 0.152) group differed statistically significantly (p ≤ 0.001) from the reference group ‘18–29 years’. Participants with self-reported somatic health conditions (+ 4.02, p < 0.001) and women (+ 1.61, p < 0.001) showed higher K10 scores. In addition, participants with compulsory education or less had scores that were higher than those from participants with secondary or vocational training (− 1.04, p < 0.001) or from those with a university degree (− 1.55, p = 0.011). Comparisons of countries against the reference category (Germany) showed statistically significant differences for all countries but Italy (p = 0.943) and France (p = 0.610). Austria − 0.62 points (p = 0.43) and the Netherlands − 1.42 points (p < 0.001) had lower scores compared to Germany, while Poland + 0.97 points (p = 0.002) and Spain + 1.68 points (p < 0.001) had higher scores. The results are displayed in Table 3; additional results for the K6 scale are given in Supplementary Table 3. Further multivariable regression analyses were done to quantify possible sampling bias (regarding underrepresentation of individuals with mental disorders) by investigating the association between the prevalence of mental disorders and K10 and K6 scores. For the K10 a, for example, 5% higher prevalence of mental disorders in the sample would result in a is 0.43 points higher mean score (please see Supplementary Table 6 for further details).

Diagnostic accuracy of the K10 scale for predicting self-reported mental health disorders

We conducted a ROC analysis to investigate the diagnostic accuracy of the K10 scale for predicting self-reported mental health disorders and determined the thresholds. The diagnostic accuracy for this criterion was high across countries with AUC values ranging from 0.77 (Italy) to 0.87 (Germany). The thresholds providing the highest sensitivity and specificity (i.e., maximal Youden J) ranged from 7.5 points (Italy) to 16.5 (Spain). When selecting a cut-off score with at least a sensitivity of 0.80, the cut-off scores ranged from 5.5 (Austria) to 13.5 (France). Additional results are reported in Supplementary Table 1. Details on the analysis for the K6 scale are reported in Supplementary Table 4.

Discussion

The results of our analysis provide age- and sex-specific general population normative data based on the K10 and K6 scales for seven European countries. Our descriptive analysis found that women and younger participants had higher distress levels than men and older participants across all analysed countries. This association of sex and age with K10 scores was also found using a multivariable regression model adjusted for country, educational level and self-reported somatic health conditions. In this model, the group differences in scores were below 2 points for all analysed variables, except for somatic health conditions and specific age groups. In a separate univariate analysis, we also investigated the differences in K10 scores between participants with and without self-reported mental conditions and found a difference of 9.11 points (about 1.2 SD). This large difference reflects the discriminatory power of the K10 that was also shown in a ROC analysis using self-reported mental conditions as criterion. In this analysis, the diagnostic accuracy in terms of AUC and the optimal cut-off scores varied substantially across countries similarly to the prevalence of these self-reported conditions.

We sampled and weighted the collected sample to match the sex and age distributions in the respective countries. The other sample characteristics were largely aligned with the available data31,32, with education level being the most notable exception. The comparison of the distribution of educational levels in our samples against the general population was challenging because of the limited availability of detailed international data and variation within educational systems. After comparing our data with OECD data, however, we identified an over-representation of higher educated individuals in our sample33. While using an online panel data company to collect data is a common technique for collecting normative data, sampling biases regarding educational levels in this recruitment strategy have been reported previously34. However, this bias may be of limited importance because of the rather small association of K10 scores with education level in our multivariable analysis results. In our samples, the lack of data on self-reported mental health disorders that can be compared against national data is a more important limitation because the definitions of these disorders differ to some degree across studies, which compromises our conclusions about their possible differences. In addition, individuals with mental health disorders may be less likely to participate in online surveys (please note that this might also be a source of bias for community health studies relying on a similar assessment methodologies). Therefore, we provided multivariable regression models that allow to estimate normative scores as a function of prevalence of mental health disorders.

Following health conditions, age was found to have the strongest association with K10 scores, which is consistent with studies that also reported lower distress levels in older individuals35,36,37. Sex differences regarding psychological distress have also been described consistently in the literature in relation to biological determinants38 and social factors but have also been reported to be context-specific26. It is noteworthy that the impact of sex on K10 scores in our large general population dataset was small in relation to the participants’ other characteristics. These results may partially reflect the sex invariance in the construct validity of the scale39,40, which suggests that the observed differences in K10 scores may reflect the true differences in psychological distress rather than being a result of the variation in measurement characteristics or response styles that may inflate the actual differences between women and men.

The variation of K10 mean scores across countries was substantial, with a similar magnitude in the difference between the Netherlands and Spain to the difference between individuals with and without somatic health conditions. When we compared our results against normative data from the literature, the scores in European countries were higher than in the Australian general population41 with its reported K10 mean score of 4.5 points (on a 0–40 metric), while age and sex differences were of the same magnitude. Even lower mean scores were observed in a Swiss community study (random sampling of adults aged 19–45 years) that found a mean 2.5 score for the K10 scale (on a 0–40 metric). However, the comparison of K10 scores across countries is compromised by the variation in sampling methodologies. Therefore, the uniform data collection approach in our study is a major strength because it improves the comparability of mean scores across various countries, which in turn supports the importance of collecting country-specific normative data.

Cross-cultural variation has been shown for the K10 scale not only in normative data but also in its measurement characteristics and screening properties. The K10 scale was originally developed in the English language for use in the US and Canada10, followed by large population studies in Australia13. While the development of the scale relied on sophisticated psychometric methods, it did not seem to focus on cross-cultural applicability. In their extensive review of the evidence for cultural equivalence and measurement characteristics, Stolk et al.15 highlighted the substantial variation in the factor structure or acceptability of item wording (in particular in non-Western and non-white populations) for example but did not indicate substantial differential item function for the K10 score. While this comprehensive review highlights a number of issues with cross-cultural applications of the K10 scale, it also reflects its very widespread use within a short period after its publication.

Our data were collected before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. A potential concern would be how the pandemic has shaped psychological distress in the general population. While some studies suggest that there were immediate increases in general population psychological distress during the first months of the pandemic42,43, a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies found only small and heterogeneous effects44. Moreover, longitudinal survey data indicates that no enduring or sustained effect on common mental health problems or psychological distress was present after the first two lockdowns and psychological returned to baseline (ie, pre-pandemic) levels42.

Our study is the first to collect multinational normative data for the K10 and K6 scales from European countries using a consistent sampling approach. These normative data facilitate more meaningful interpretations of patient- or group-level K10 and K6 data in the European setting. In addition, these data can inform health-care professionals, researchers and policymakers about the levels of general distress in groups of individuals with specific characteristics. Furthermore, the data facilitate the interpretation of scores from clinical populations or in clinical studies and may also be used to estimate the pre-disease distress levels in a mental health context. By relying on the uniform data collection and sampling methods in all countries, our data can also be used in country comparisons.

Data availability

Data will not be shared via a public data repository. Data may be available upon reasonable request form the corresponding author.

References

Steel, Z. et al. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. Int. J. Epidemiol. 43(2), 476–493 (2014).

GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet 390 (16), 1211–59 (2017).

OECD/European Union. Health at a Glance: Europe 2018: State of Health in the EU Cycle. Paris/European Union, Brussels. URL: https://doi.org/10.1787/health_glance_eur-2018-en (2018).

Baumann, A. E. Stigmatization, social distance and exclusion because of mental illness: The individual with mental illness as a “stranger”. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 19(2), 131–135 (2007).

Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B., Gibbon, M. & First, M. B. The structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). I: History, rationale, and description. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 49(8), 624–629 (1992).

Robins, L. N. et al. The composite international diagnostic interview. An epidemiologic Instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 45(12), 1069–1077 (1988).

Ukatu, N., Clare, C. A. & Brulja, M. Postpartum depression screening tools: A review. Psychosomatics 59(3), 211–219 (2018).

Thabtah, F. & Peebles, D. Early autism screening: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18(16), 3502 (2019).

Krause, K. R. et al. International consensus on a standard set of outcome measures for child and youth anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Lancet Psychiatry 8(1), 76–86 (2021).

Kessler, R. C. et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 32(6), 959–976 (2002).

Brooks, R. T., Beard, J. & Steel, Z. Factor structure and interpretation of the K10. Psychol. Assess. 18(1), 62–72 (2006).

Cairney, J., Veldhuizen, S., Wade, T. J., Kurdyak, P. & Streiner, D. L. Evaluation of 2 measures of psychological distress as screeners for depression in the general population. Can. J. Psychiatry 52(2), 111–120 (2007).

Furukawa, T. A., Kessler, R. C., Slade, T. & Andrews, G. The performance of the K6 and K10 screening scales for psychological distress in the Australian National survey of mental health and well-being. Psychol. Med. 33(2), 357–362 (2003).

Furukawa, T. A. et al. The performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the world mental health survey Japan. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 17(3), 152–158 (2008).

Stolk, Y., Kaplan, I. & Szwarc, J. Clinical use of the Kessler psychological distress scales with culturally diverse groups. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 23(2), 161–183 (2014).

Scott, E. M. et al. Distress and disability in young adults presenting to clinical services with mood disorders. Int. J. Bipolar Disord. 1, 1–8 (2017).

Cashin, A., Browne, G., Bradbury, J. & Mulder, A. The effectiveness of narrative therapy with young people with autism. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 26(1), 32–41 (2013).

Fassaert, T. et al. Psychometric properties of an interviewer-administered version of the Kessler psychological distress scale (K10) among Dutch, Moroccan and Turkish respondents. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 18(3), 159–168 (2009).

Staples, L. G. et al. Psychometric properties and clinical utility of brief measures of depression, anxiety, and general distress: The PHQ-2, GAD-2, and K-6. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 56, 13–18 (2013).

Cornelius, B. L., Groothoff, J. W., van der Klink, J. J. & Brouwer, S. The performance of the K10, K6 and GHQ-12 to screen for present state DSM-IV disorders among disability claimants. BMC Public Health 13, 1–8 (2013).

Hoffman, J. et al. Construct validity and factor structure of the Kessler-10 in South Africa. BMC Psychol. 10(1), 177 (2018).

Peixoto, E. M., Zanini, D. S. & de Andrade, J. M. Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric properties of the Kessler Distress Scale (K10): An application of the rating scale model. Psicol. Reflex. Crit. 34(1), 21 (2019).

Vasiliadis, H. M., Chudzinski, V., Gontijo-Guerra, S. & Préville, M. Screening instruments for a population of older adults: The 10-item Kessler psychological distress scale (K10) and the 7-item generalized anxiety disorder scale (GAD-7). Psychiatry Res. 228(1), 89–94 (2015).

Carrà, G. et al. Do they actually work across borders? Evaluation of two measures of psychological distress as screening instruments in a non Anglo-Saxon country. Eur. Psychiatry 26(2), 122–127 (2011).

Searle, A. K. et al. Screening for depression and psychological distress in a currently serving military population: The diagnostic accuracy of the K10 and the PHQ9. Assessment 26(8), 1411–1426 (2019).

Dotti Sani, G.M., Molteni, F., Sarti, S. Boys do cry: Age and gender differences in psycho-physiological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Appl. Qual. Life Res.1–26, (2022).

EORTC Quality of Life Group et al. Estimation of an EORTC QLU-C10 value set for Spain using a discrete choice experiment. Pharmacoeconomics 39(9), 1085–1098 (2021).

EORTC Quality of Life Group et al. Dutch utility weights for the EORTC cancer-specific utility instrument: the Dutch EORTC QLU-C10D. Qual. Life Res. 30(7), 2009–2019 (2021).

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Group et al. EORTC QLU-C10D value sets for Austria, Italy, and Poland. Qual. Life Res. 29(9), 2485–2495 (2020).

United Nations. UN Data: A world of information. URL: http://data.un.org/ (2015).

OECD. Health at a Glance: Europe 2014: Diabetes prevalence and incidence. Paris: OECD. URL: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/health-at-a-glance-europe-2014/diabetes-prevalence-and-incidence_health_glance_eur-2014-17-en;jsessionid=7E-qb7MSHDx2HMgkRnXnMGsx5qqTmO3f3q86M-Er.ip-10-240-5-5 (2014).

Central Intelligence Agency. Country Comparison :: HIV/AIDS - adult prevalence rate. URL: https://web.archive.org/web/20201017190456/https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/rawdata_363.txt (2019).

OECD. Population with tertiary education. https://doi.org/10.1787/0b8f90e9-en (2022).

EORTC Quality of Life Group et al. General population normative data for the EORTC QLQ-C30 health-related quality of life questionnaire based on 15,386 persons across 13 European countries, Canada and the Unites States. Eur. J. Cancer 107, 153–163 (2019).

Hussain, R., Wark, S., Dillon, G. & Ryan, P. Self-reported physical and mental health of Australian carers: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 6(9), e011417 (2016).

Kelly, B. J. et al. Mental health and well-being within rural communities: The Australian rural mental health study. Aust. J. Rural Health 18(1), 16–24 (2010).

Sunderland, M., Hobbs, M. J., Anderson, T. M. & Andrews, G. Psychological distress across the lifespan: Examining age-related item bias in the Kessler 6 psychological distress scale. Int. Psychogeriatr. 24(2), 231–242 (2012).

Wang, J. et al. Gender difference in neural response to psychological stress. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 3, 227–239 (2007).

Drapeau, A. et al. A life-course and time perspective on the construct validity of psychological distress in women and men. Measurement invariance of the K6 across gender. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 10, 1–16 (2010).

Baillie, A. J. Predictive gender and education bias in Kessler’s psychological distress scale (k10). Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 40(9), 743–748 (2009).

Slade, T., Grove, R. & Burgess, P. Kessler psychological distress scale: normative data from the 2007 Australian national survey of mental health and wellbeing. Aust. New Zealand J. Psychiatry 45(4), 308–316 (2011).

Taxiarchi, V. P. et al. Changes to healthcare utilisation and symptoms for common mental health problems over the first 21 months of the COVID-19 pandemic: Parallel analyses of electronic health records and survey data in England. Lancet Reg. Health https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2023.100697 (2023).

Xiong, J. et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 277, 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001 (2020).

Prati, G. M. A. D. he psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns: A review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies and natural experiments. Psychol. Med. 51(2), 201–211 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants of the study for their valuable time and input without which the study would not have been possible.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L., M.P. and J.M.G. wrote and edited the manuscript and analysed the data. B.H. and G.K. conceived the study, acquired the data, and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors have red and approved the current version of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lehmann, J., Pilz, M.J., Holzner, B. et al. General population normative data from seven European countries for the K10 and K6 scales for psychological distress. Sci Rep 13, 18389 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-45124-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-45124-0

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.