Abstract

Previous research has shown that both the daily experiences and personal traits of adolescents are linked to aggression. Our aim was to further investigate the relationship between leisure experience, self-esteem, and aggression according to the general aggression model. In addition, within frustration-aggression theory, we proposed that leisure experience and aggression have a negative correlation. Furthermore, based on broaden-and-build theory, we explored the mediating role of self-esteem between leisure experience and aggression. The participants included 660 Chinese teenagers with an average age of 14.3. Among them, male students accounted for 310 (49.4%) and female students accounted for 318 (50.6%). The results showed that leisure experience was positively correlated with self-esteem and negatively correlated with aggression, while self-esteem was also negatively correlated with aggression. Additionally, self-esteem fully mediated the relationship between leisure experience and aggression. Our study could enrich research on leisure and provide a basis for protective factors of aggression in adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aggression is a type of anti-social behavior that is performed with the purpose of harming other individuals or groups. It basically appears in the forms of physical, verbal or relational aggression1. According to an American study, 23.6% of adolescents in Grades 9–12 reported experiencing at least one incident of physical conflict within a year2. Globally, interpersonal violence is the fourth leading cause of death among 15–19-year-olds, with a mortality rate of 5.5%3. On the one hand, levels of aggression may increase during adolescence4. On the other hand, both perpetrators and victims of aggressive behaviors may suffer long-term negative consequences. In previous studies, engagement in aggressive behaviors is associated with an increased risk of future negative socioeconomic consequences and participation in later violent and nonviolent crimes5,6. In addition, victims are likely to experience mental health problems7. Therefore, in this study, we expected to explore factors that might be related to aggression in adolescents.

The general aggression model states that personal and situational factors influence the ultimate aggressive behaviors through the present internal state8. In general, aggression can be displayed and learned in a variety of settings, including family, school, and daily recreation9,10,11. As a situational factor, satisfying leisure experience was found to be negatively associated with aggression12. As an individual trait, lower self-esteem is also closely related to aggression13,14. However, as far as we are concerned, no study has investigated the relationship between leisure experience, self-esteem and aggression, which is the main goal of this study.

Leisure experience and aggression

Leisure experience refers to the participants’ perceived significance of the leisure activity, which is a construct with a theoretical tradition and practical application15. The perception of freedom, competence, intrinsic motivation, relatedness and control are central to many leisure experiences16,17,18. We primarily focus on perceived freedom, perceived competence, and perceived intrinsic motivation in our research, considering that these three kinds of experience are closely related19.

As a period of nonobligatory time, leisure, in which people seek marvelous experiences of self-determination, is thought of as compensation for work16. In a sense, leisure time without the perception of freedom, competence and intrinsic motivation is probably considered a failure20,21, which has a link to the feeling of depression, anxiety and distress22,23. Within the framework of frustration-aggression theory, frustration, defined as irritable distress from limitation, exclusion and failure, may provoke defensive or aggressive behavioral responses24. From this perspective, positive leisure experience is likely to be negatively associated with aggression. As research has demonstrated, wonderful experiences in leisure time have a correlation with reduced aggression25. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1

Adolescents' leisure experience is negatively correlated with aggression.

The mediating role of self-esteem

Self-esteem is an individual's self-assessment that reflects how much he appreciates himself26. Traditionally, lower self-esteem may be mutually related to certain negative outcomes, such as externalizing problems such as aggression27. As some scholars have argued, individuals with lower self-esteem may act aggressively to avoid feelings of inferiority brought on by failure28,29. Additionally, a meta-analytical study of Chinese students found a moderate negative correlation between self-esteem and aggression30. Based on this evidence, we consider that self-esteem as an individual cognitive factor might be negatively correlated with aggression.

Moreover, broaden-and-build theory proposes that experiences of positive emotion may contribute to the construction of higher self-evaluations31. As has been proven, positive feelings can build lasting personal resources, including self-acceptance and self-esteem32. Similarly, a pleasant leisure experience was generally positively associated with self-esteem in the former research. For instance, leisure satisfaction has been shown to have a positive impact on self-esteem33. Research has also confirmed that engaging in gratifying entertainment programs is positively associated with self-esteem and self-concept34.

Therefore, in the aforementioned case that both leisure experience and self-esteem may relate to aggression, we additionally propose that the relationship between leisure experience and aggression could be mediated by self-esteem. Self-esteem has often been used as a mediator between different experiences and behavioral problems among adolescents, for example, ostracism and aggression35, school disconnectedness and Internet addiction36, and peer victimization and problem behaviors37. In summary, according to the related findings of leisure experience, aggression and self-esteem, we propose the second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2

Self-esteem plays a mediating role between leisure experience and aggression.

Materials and methods

Sample and procedure

Participants included 660 students recruited from two high schools and two junior high schools in a mid-sized city of China. Participants were volunteers who were told the content of the questionnaires and agreed that the data could be used in the study. We collected 628 students (average age = 14.3) after removing invalid questionnaires (blank, missing more than five questions or having more than five repeat options). Among them, there were 310 (49.4%) male students and 318 (50.6%) female students. In addition, there were 300 (47.8%) junior high school students and 328 (52.2%) high school students.

This research was conducted from March 2021 to June 2021. Our research team members and one teacher from each school of participants were trained in advance to ensure the quality of the questionnaires. The experimenters first read the instructions and the principle of confidentiality and subsequently organized students to answer the questionnaires. The answering time was limited to 20 min.

Measures

Leisure experience

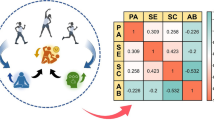

This study used the leisure experience scale developed by Hairong Yu38. The scale consists of four factors: perceived freedom, perceived intrinsic motivation, perceived competence, and perceived extrinsic motivation. We used the first three factors to assess the leisure experience of adolescents. Among them, perceived freedom includes four questions, such as "I can freely spend my leisure time." Perceived intrinsic motivation includes eight questions, such as "I find a lot of fun in leisure activities." In addition, perceived competence contains four questions, such as "I think leisure activities can improve some of my abilities." In this study, the Cronbach's alpha of the total scale was 0.91, and the Cronbach's alphas of the three subscales were 0.81 for perceived freedom, 0.90 for perceived intrinsic motivation, and 0.83 for perceived competence. In addition, χ2/df = 4.52, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.92, GFI = 0.91, NFI = 0.92, AGFI = 0.88, and RMSEA = 0.075. We specified the SEM of this scale in Fig. 1, in which the factor loadings and factor intercorrelations are provided. Using a four-point Likert scale, the participants were asked to choose from 1 (completely inconsistent) to 5 (completely consistent). A higher score indicates a higher level of leisure experience.

Aggression

This study adopted the Chinese version of the Buss–Perry aggression questionnaire39. The scale consists of 20 items, which are categorized into four dimensions: physical aggression, anger, hostility, and substitution aggression. The scale was rated on a four-point Likert scale. The participants were asked to choose from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree), with a higher score indicating a higher tendency of aggression. In this study, the Cronbach's alpha of the total scale was 0.88, and the Cronbach's alphas of the four dimensions were 0.77 for physical aggression, 0.85 for anger, 0.81 for hostility, and 0.79 for substitution aggression.

Self-esteem

We used the self-esteem scale (SES) in this study40. This scale comprises 10 items, five of which are reverse scored. Using a four-point Likert scale, the participants were asked to choose from 1 (completely inconsistent) to 4 (completely consistent). A higher score indicates higher self-esteem. In this study, the Cronbach's alpha of the scale was 0.88.

Statistical procedure

We used SPSS 21.0 and AMOS 24.0 to analyze the data. SPSS was used for descriptive analysis, Pearson correlation analysis and linear regression analysis. To determine the mediating effect of self-esteem, we conducted SEMs using 5000 bootstrap samples and the 95% bias-corrected confidence interval (95% CI) in AMOS. The level of statistical significance was set as p < 0.05.

Ethical statement

Our research was based on the ethical standards in the WMA Declaration in Helsinki and was approved by the research ethics committee of Qingdao University, China. We informed all participants of the study before the test. The research was conducted after the consent of the participants. In addition, our data were anonymized to ensure the privacy of all participants.

Results

The common method bias examination

Since data for this study were collected by self-report questionnaires, we used confirmatory factor analysis to test all items for common method bias41, and the results show that the model fit did not fit well, χ2/df = 10.78 > 3, RMSEA = 0.121 > 0.08, NFI = 0.44 < 0.9, CFI = 0.47 < 0.9. Therefore, there was no serious common method deviation.

Descriptive statistics and correlations

The means (M) and standard deviations (SD) for all variables are displayed in Table 1. The results of correlations can be seen in Table 1 as well. As the table shows, there was a positive correlation between leisure experience and self-esteem (r = 0.49, p < 0.01) and a negative correlation between leisure experience and aggression (r = − 0.35, p < 0.01). Self-esteem was negatively correlated with aggression (r = − 0.71, p < 0.01).

Linear regression analysis

To further explore the relationship between leisure experience and aggression, we performed linear regression tests. We used gender as a control variable, the four dimensions of leisure experience as independent variables, and aggression as a dependent variable. Linear regression analysis was performed using the "enter" method. The results can be seen in Table 2. After controlling for all other leisure experiences, perceived freedom (β = − 0.12, p = 0.009), perceived intrinsic motivation (β = − 0.13, p = 0.007), and perceived competence (β = − 0.18, p < 0.001) were all negatively correlated with aggression. They totally predicted 12% of the variance of aggression.

The mediating effect of self-esteem on leisure experience and aggression

To test the relationship between variables, we used SEMs to estimate two models: (1) a model that includes only direct paths and (2) a model that contains both direct and indirect paths. We considered leisure experience as the independent variable, self-esteem as the mediating variable, aggression as the dependent variable, and gender as the control variable to conduct two models in AMOS. The results are shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

In model 1, leisure experience was significantly negatively associated with aggression (β = − 0.49, p < 0.001). However, in model 2, after self-esteem (mediating variable) was added, the correlation between leisure experience and aggression was no longer significant (β = − 0.04, p = 0.455). Meanwhile, there was a significant correlation between leisure experience and self-esteem (β = 0.57, p < 0.001) as well as between self-esteem and aggression (β = − 0.81, p < 0.001).

Table 3 demonstrates the model fit indicators and the results of the χ2 difference test of specific structural models. In Model 1, χ2/df = 3.85, CFI = 0.949, RMSEA = 0.069, RMR = 0.028. For Model 2, χ2/df = 3.45, CFI = 0.963, RMSEA = 0.069, RMR = 0.022. Furthermore, the χ2 difference test shows that ∆χ2 (6) = 13, p = 0.043, and model 2 was superior to model 1. In model 2, the direct effect value was − 0.031 (95% CI [− 0.128, 0.063], p = 0.586), the indirect effect value was − 0.410 (95% CI [− 0.509, − 0.335], p = 0.005), and the total effect value was − 0.441 (95% CI [− 0.544, − 0.344], p = 0.009). These results suggest that the relationship between leisure experience and aggression was fully mediated by self-esteem.

Discussion

Our study was intended to examine the relationship between leisure experience, self-esteem and aggression based on the general aggression model. First, on the basis of frustration-aggression theory, we proposed that leisure experience is negatively correlated with aggression, and the results supported this hypothesis. Second, within the broaden-and-build theory, we suggested that self-esteem may play a mediating role between leisure experience and aggression. The results also confirmed this hypothesis. Overall, our study extends the general aggression model and provides certain evidence for the relationship between leisure experience, self-esteem, and aggression.

Leisure experience and aggression

Consistent with previous research42, we found that leisure experience was negatively correlated with aggression. To our knowledge, this is the first time that we have incorporated multiple perceptions of freedom, intrinsic motivation and competence into leisure experience and examined their relationship with aggression. Our research is dedicated to discovering the benefits of leisure for the healthy development of adolescents. On the whole, great leisure experience is often associated with many positive outcomes, such as psychological well-being43 and lower levels of stress44, and both have a negative connection with externalizing behavioral problems45.

On the basis of the linear regression analysis, perceived freedom, perceived intrinsic motivation and perceived competence of leisure experience were all negatively correlated with aggression after controlling for gender. Perceptions of these three kinds of experience are generally associated with adaptive psychosocial functioning46,47. Leisure is sometimes seen as compensation for other areas of life, probably because individuals can gain a deep sense of satisfaction in their perceptions of freedom, competence, and intrinsic motivation48. Moreover, positive leisure experiences could effectively reduce people's stress and depression49, which are often seen as risk factors for aggression50.

In contrast, the absence of any of the above experiences may cause frustration, which, according to frustration-aggression theory, could trigger aggression. In a previous study, the classroom environment in which students' sense of autonomy was frustrated encouraged bullying and interpersonal aggression51. Another study found that frustration with competence in electronic games indicates a greater likelihood of aggressive behaviors52.

An interesting finding was that the direct effect between leisure experience and aggression was no longer significant after the mediator variable (self-esteem) was added. This may be because the leisure experience investigated was recalled by individuals, while self-esteem is a relatively stable personal trait. As a cognitive trait, self-esteem may be one of the key mechanisms explaining levels of aggression.

The mediating role of self-esteem

Similar to previous studies, we specifically focused on the potential mediating variable between leisure and aggression53. Our study found that self-esteem fully mediated the relationship between leisure experience and aggression, suggesting that perhaps certain cognitive factors, such as self-esteem, may play an intermediary role between individuals’ daily experiences and aggression. Self-esteem is widely influenced by the social environment and individuals’ own experiences54, and it is also thought to be a possible antecedent of behaviors27,55. Some theories suggest that to avoid the lowering of self-concept, individuals may show externally oriented anger after the threat to the ego56.

Individuals could derive many psychological benefits from leisure, such as positive self-concept57, profiting from the enjoyable experience during free time. During adolescence, a high sense of mastery and autonomy is connected with higher self-esteem58,59, and these perceptions are often regarded as essential components of the leisure experience. Furthermore, Ryan and Deci60 pointed out that intrinsic motivation is also associated with many positive effects, such as high levels of creativity, energy, and self-esteem. These results support the broaden-and-build theory, in which positive emotions, as accumulated and compounded, gradually become a lasting individual resource. Conversely, negative experience is usually associated with higher levels of aggression and lower self-esteem61.

On another aspect, based on our research, self-esteem and aggression are negatively correlated. Numerous studies have demonstrated this result. For instance, Morsünbül13 found that self-esteem could predict the levels of aggression during adolescence and adulthood. Self-esteem is an important construct in the process of individual growth, and it frequently plays a protective role in various psychological symptoms62. For adolescents, improving self-esteem may help prevent aggressive behaviors14.

Conclusions and limitations

In short, the results supported two hypotheses, which are as follows: (1) leisure experience was negatively associated with aggression; (2) Self-esteem mediated the relationship between leisure experience and aggression. These results extend the general aggression model and provide some evidence for factors might be associated with aggression in adolescents. In our view, the broad benefits that leisure may bring to adolescents are worthy of attention. At the same time, the role of adolescents' intrapersonal traits also needs to be considered.

There are some limitations to our research as well. First, the study was based on cross-sectional data. Nevertheless, the results may differ from those based on longitudinal data. To further verify the relationship between these three variables, we may need long-term follow-up. In addition, adolescents' self-reported aggression may be concealed so that we could use other ways to make the data more accurate, such as adding observations from teachers or parents.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in “OSF” at https://osf.io/fdq4h/. Identifier: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/FDQ4H.

References

Krahé, B. Risk factors for the development of aggressive behavior from middle childhood to adolescence: The interaction of person and environment. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 29, 333–339 (2020).

Kann, L. et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 67, 1 (2018).

Mokdad, A. H. et al. Global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors for young people’s health during 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 387, 2383–2401 (2016).

Lynne-Landsman, S. D., Graber, J. A., Nichols, T. R. & Botvin, G. J. Trajectories of aggression, delinquency, and substance use across middle school among urban, minority adolescents. Aggress. Behav. 37, 161–176 (2011).

Moore, S. E. et al. Impact of adolescent peer aggression on later educational and employment outcomes in an Australian cohort. J. Adolesc. 43, 39–49 (2015).

Gilman, A. B. et al. Understanding the relationship between self-reported offending and official criminal charges across early adulthood. Crim. Behav. Ment. Health 24, 229–240 (2014).

Henriksen, M. et al. Developmental course and risk factors of physical aggression in late adolescence. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 52, 628–639 (2021).

Anderson, C. A. & Bushman, B. J. Human aggression. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 53, 27–51 (2002).

Labella, M. H. & Masten, A. S. Family influences on the development of aggression and violence. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 19, 11–16 (2018).

Poling, D. V., Smith, S. W., Taylor, G. G. & Worth, M. R. Direct verbal aggression in school settings: A review of the literature. Aggress. Violent Behav. 46, 127–139 (2019).

Prescott, A. T., Sargent, J. D. & Hull, J. G. Metaanalysis of the relationship between violent video game play and physical aggression over time. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, 9882–9888 (2018).

Lee H. R., Jeong E. J. & Kim J. W. Role of internal health belief, catharsis seeking, and self-efficacy in game players' aggression. In Proceedings of the 2016 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), (2016).

Morsünbül Ü. The effect of identity development, self-esteem, low self-control and gender on aggression in adolescence and emerging adulthood. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 99–116 (2015).

Babore, A., Carlucci, L., Cataldi, F., Phares, V. & Trumello, C. Aggressive behaviour in adolescence: Links with self-esteem and parental emotional availability. Soc. Dev. 26, 740–752 (2017).

Codina, N. & Pestana, J. V. Time matters differently in leisure experience for men and women: Leisure dedication and time perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 2513 (2019).

Coleman, D. & Iso-Ahola, S. E. Leisure and health: The role of social support and self-determination. J. Leis. Res. 25, 111–128 (1993).

Leversen, I., Danielsen, A. G., Birkeland, M. S. & Samdal, O. Basic psychological need satisfaction in leisure activities and adolescents’ life satisfaction. J. Youth Adolesc. 41, 1588–1599 (2012).

Webb, E. & Karlis, G. Theoretical developments in leisure studies: A look at perceived freedom and intrinsic motivation. Loisir et Société/Society and Leisure 40, 268–283 (2017).

Painter J. Autonomy, competence, and intrinsic motivation in science education: A self-determination theory perspective. (2011).

Yuen, F. “If we’re lost, we are lost together”: Leisure and relationality. Leis. Sci. 43, 90–96 (2021).

Koka, A., Tilga, H., Kalajas-Tilga, H., Hein, V. & Raudsepp, L. Perceived controlling behaviors of physical education teachers and objectively measured leisure-time physical activity in adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 2709 (2019).

Chen, F. et al. Effects of a hospital-based leisure activities programme on nurses’ stress, self-perceived anxiety and depression: A mixed methods study. J. Nurs. Manag. 30, 243–251 (2022).

Lepp, A., Barkley, J. E. & Li, J. Motivations and experiential outcomes associated with leisure time cell phone use: Results from two independent studies. Leis. Sci. 39, 144–162 (2017).

Breuer, J. & Elson, M. Frustration-Aggression Theory (Wiley Blackwell, 2017).

Dwivedi, U., Kumari, S., Akhilesh, K. & Nagendra, H. Well-being at workplace through mindfulness: Influence of Yoga practice on positive affect and aggression. Ayu 36, 375 (2015).

Orth, U., Erol, R. Y. & Luciano, E. C. Development of self-esteem from age 4 to 94 years: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Bull. 144, 1045 (2018).

Donnellan, M. B., Trzesniewski, K. H., Robins, R. W., Moffitt, T. E. & Caspi, A. Low self-esteem is related to aggression, antisocial behavior, and delinquency. Psychol. Sci. 16, 328–335 (2005).

Ostrowsky, M. K. Are violent people more likely to have low self-esteem or high self-esteem?. Aggress. Violent Behav. 15, 69–75 (2010).

Zapf D. & Einarsen S. Individual antecedents of bullying: victims and perpetrators. In Bullying and Emotional Abuse in the Workplace. 183–202 (CRC Press, 2002).

Teng, Z., Liu, Y. & Guo, C. A meta-analysis of the relationship between self-esteem and aggression among Chinese students. Aggress. Violent Behav. 21, 45–54 (2015).

Fredrickson, B. L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 56, 218 (2001).

Vacharkulksemsuk T. & Fredrickson B. L. Looking back and glimpsing forward: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions as applied to organizations. In Advances in Positive Organizational Psychology 45–60 (2013).

Won, C. M. & Cho, T. The effects of adolescents’ leisure activity on leisure satisfaction, self-esteem and quality of life. J. Tourism Sci. 36, 145–165 (2012).

Huang, C.-L., Yang, S. C. & Chen, A.-S. Motivations and gratification in an online game: Relationships among players’ self-esteem, self-concept, and interpersonal relationships. Soc. Behav. Pers. 43, 193–203 (2015).

Li, S., Zhao, F., Yu, G. J. C. & Review, Y. S. Ostracism and aggression among adolescents: Implicit theories of personality moderated the mediating effect of self-esteem. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 100, 105–111 (2019).

Peng, W. et al. School disconnectedness and Adolescent Internet Addiction: Mediation by self-esteem and moderation by emotional intelligence. Comput. Hum. Behav. 98, 111–121 (2019).

Pan, Y. et al. Peer victimization and problem behaviors: The roles of self-esteem and parental attachment among Chinese adolescents. Child Dev. 91, e968–e983 (2020).

Yu H. 初中生休闲感受及其与自尊、攻击性行为关系的研究——以青岛市E中学为例 [A study on leisure experience of junior high school students and its relationship with self-esteem and aggressive behavior], [Master's thesis], (Qingdao University, 2021).

Liu J., Zhou Y. & Wenyu G. Reliability and validity of Chinese version of Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire in adolescents. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. (2000).

Rosenberg, M. Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSE). Accept. Commit. Ther. Meas. Packag. 61, 18 (1965).

Cole, D. A. Utility of confirmatory factor analysis in test validation research. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 55, 584 (1987).

Park, S., Chiu, W. & Won, D. Effects of physical education, extracurricular sports activities, and leisure satisfaction on adolescent aggressive behavior: A latent growth modeling approach. PLoS ONE 12, e0174674 (2017).

Freire, T. & Teixeira, A. The influence of leisure attitudes and leisure satisfaction on adolescents’ positive functioning: The role of emotion regulation. Front. Psychol. 9, 1349 (2018).

Bedini, L. A., Labban, J. D., Gladwell, N. J. & Dudley, W. N. The effects of leisure on stress and health of family caregivers. Int. J. Stress. Manag. 25, 43 (2018).

Lombas, A. S. et al. Impact of the happy classrooms programme on psychological well-being, school aggression, and classroom climate. Mindfulness 10, 1642–1660 (2019).

Houtepen, J., Sijtsema, J., Klimstra, T., Van Der Lem, R. & Bogaerts, S. Loosening the reins or tightening them? Complex relationships between parenting, effortful control, and adolescent psychopathology. Child Youth Care Forum 48, 127–145 (2019).

Vasquez, A. C., Patall, E. A., Fong, C. J., Corrigan, A. S. & Pine, L. Parent autonomy support, academic achievement, and psychosocial functioning: A meta-analysis of research. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 28, 605–644 (2016).

Walker, G. J. & Kono, S. The effects of basic psychological need satisfaction during leisure and paid work on global life satisfaction. J. Posit. Psychol. 13, 36–47 (2018).

Vella, E. J., Milligan, B. & Bennett, J. L. Participation in outdoor recreation program predicts improved psychosocial well-being among veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder: A pilot study. Mil. Med. 178, 254–260 (2013).

Dutton, D. G. & Karakanta, C. Depression as a risk marker for aggression: A critical review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 18, 310–319 (2013).

Roth, G., Kanat-Maymon, Y. & Bibi, U. Prevention of school bullying: The important role of autonomy-supportive teaching and internalization of pro-social values. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 81, 654–666 (2011).

Przybylski, A. K., Deci, E. L., Rigby, C. S. & Ryan, R. M. Competence-impeding electronic games and players’ aggressive feelings, thoughts, and behaviors. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 106, 441–457 (2014).

Espinosa, P. & Clemente, M. Self-transcendence and self-oriented perspective as mediators between video game playing and aggressive behaviour in teenagers. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 23, 68–80 (2013).

Sharma, P. Role of basic psychological needs satisfaction in self esteem and aggression. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 10, 986–1008 (2022).

Fu, X., Padilla-Walker, L. M. & Brown, M. N. Longitudinal relations between adolescents’ self-esteem and prosocial behavior toward strangers, friends and family. J. Adolesc. 57, 90–98 (2017).

Baumeister, R. F., Smart, L. & Boden, J. M. Relation of threatened egotism to violence and aggression: The dark side of high self-esteem. Psychol. Rev. 103, 5 (1996).

Blomfield, C. J. & Barber, B. L. Developmental experiences during extracurricular activities and Australian adolescents’ self-concept: Particularly important for youth from disadvantaged schools. J. Youth Adolesc. 40, 582–594 (2011).

Hein, V. et al. The perception of the autonomy supportive behaviour as a predictor of perceived effort and physical self-esteem among school students from four nations. Montenegrin J. Sports Sci. Med. 7, 21–30 (2018).

Erol, R. Y. & Orth, U. Self-esteem development from age 14 to 30 years: A longitudinal study. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 101, 607 (2011).

Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 25, 54–67 (2000).

Yu, B.-L., Li, J., Liu, W., Huang, S.-H. & Cao, X.-J. The effect of left-behind experience and self-esteem on aggressive behavior in young adults in China: A cross-sectional study. J. Interpers. Violence 37, 1049–1075 (2022).

Arslan, G. Psychological maltreatment, emotional and behavioral problems in adolescents: The mediating role of resilience and self-esteem. Child Abuse Neglect 52, 200–209 (2016).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (Nos. 19BKS087) awarded to Xia Ximei.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Designed the survey: X.X., X.W., H.Y. Performed the survey: H.Y., X.W. Analyzed the data: X.W., H.Y. Contributed materials/analysis tools: X.X., H.Y. Wrote the paper: X.W., H.Y., X.X.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xia, X., Wang, X. & Yu, H. Mediating effect of self-esteem on the relationship between leisure experience and aggression. Sci Rep 12, 9903 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14125-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14125-w

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.