Abstract

There is a great demand from patients requiring skin repair, as a result of poorly healed acute wounds or chronic wounds. These patients are at high risk of constant inflammation that often leads to life-threatening infections. Therefore, there is an urgent need for new materials that could rapidly stimulate the healing process and simultaneously prevent infections. Phosphate-based coacervates (PC) have been the subject of increased interest due to their great potential in tissue regeneration and as controlled delivery systems. Being bioresorbable, they dissolve over time and simultaneously release therapeutic species in a continuous manner. Of particular interest is the controlled release of metallic antibacterial ions (e.g. Ag+), a promising alternative to conventional treatments based on antibiotics, often associated with antibacterial resistance (AMR). This study investigates a series of PC gels containing a range of concentrations of the antibacterial ion Ag+ (0.1, 0.3 and 0.75 mol%). Dissolution tests have demonstrated controlled release of Ag+ over time, resulting in a significant bacterial reduction (up to 7 log), against both non-AMR and AMR strains of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa). Dissolution tests have also shown controlled release of phosphates, Ca2+, Na+ and Ag+ with most of the release occurring in the first 24 h. Biocompatibility studies, assessed using dissolution products in contact with human keratinocyte cells (HaCaT) and bacterial strains, have shown a significant increase in cell viability (p ≤ 0.001) when gels are dissolved in cell medium compared to the control. These results suggest that gel-like silver doped PCs are promising multifunctional materials for smart wound dressings, being capable of simultaneously inhibit pathogenic bacteria and maintain good cell viability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wound management is a major area of global unmet need. Growing elderly and diabetic populations are leading to a sharp increase in the cases of chronic wounds (diabetic foot, venous, and pressure ulcers). A large proportion of these wounds are resistant to current treatments, remaining unhealed for months or years, making chronic wounds a substantial economic, social and clinical challenge1. Chronic wounds are normally associated with the proliferation of antibacterial resistance (AMR) bacteria2,3, resulting in prolonged antibiotic treatments and the subsequent increase in healthcare costs4. AMR is an additional growing global issue that poses a serious threat to public health5. In addition, increasing numbers of acute wounds result in surgical site infections, which significantly delay healing. Therefore, there is an urgent need for novel materials that are able, not only to assist with skin healing and regeneration but also to display efficient antibacterial activity.

The demand for wound treatment is extremely high, with the wound care market expected to reach $27.8bn by 2026 worldwide (compound annual growth rate 7.6%)6. Therefore, a material capable of promoting tissue regeneration and managing wound infection represent a transformative alternative to conventional dressing-based wound management (physical protection/antibacterial activity). Polyphosphate-based coacervate (PC) gels have been recently investigated as materials with a great potential in hemostasis applications, playing an important role in the coagulation cascade and decreasing blood coagulation7. Amorphous polyphosphates have also been shown to enhance wound healing when used in combination with collagen8. Moreover, in vivo studies have shown acceleration of wound closure in the presence of polyphosphate nanoparticles9,10. Being resorbable, PC are ideal controlled delivery systems, being capable of releasing therapeutic species in the physiological environment in a controlled, continuous, and timely manner. PC therefore have the potential to be multifunctional smart biomaterials, being able to induce simultaneously tissue healing/regeneration and release of therapeutic species to reduce bacterial infection7.

PC are prepared via the simple, sustainable route of coacervation11. This method consists of the slow addition of an aqueous solution of divalent ions (e.g. Ca2+, Mg2+, Mn2+) to an aqueous solution of sodium polyphosphate at room temperature. Upon addition, a phase separation occurs with the formation of a viscous, opaque lower layer (PC) and an upper aqueous layer. Following the removal of the upper layer, the as-made, gel-like PC is isolated. The synthesis of PC is very versatile, and a variety of therapeutic species, including thermal sensitive, can be added to the material. Although the polyphosphate coacervation process is well known, only recently has gained renewed attention due to its potential applications in biomedicine12.

Most of the PC studies to date focus on their synthesis12, thermal properties7, rheology13, and change of properties over time7. Some studies have investigated dried PC as bulk glass powders7 and fibres11 in terms of structure and antibacterial activity when doped7,14,15 with Ag+ or Cu2+. However, to the knowledge of the authors, the antibacterial capabilities of PC in gel form have not been explored to date. This work investigates for the first time the antibacterial effects of PC in gel form when doped with various amounts of the antibacterial metallic ion Ag+.

This work is in line with the current trend in antibacterial materials research that leads towards finding alternative non-antibiotic therapies such as treatments based on antibacterial metallic ions16 and metallic nanoparticles17, less prone to develop AMR. The versatility of the in-solution coacervation method allows the inclusion in the coacervate gel of a variety of antibacterial metallic ions such as Ag+, Cu2+, Zn2+, Ga3+ and Ce4+, which can then be released in a controlled manner in the wound site18,19. Previous studies have reported that Ag+ embedded in phosphate-based bulk glasses prepared using the traditional melt-quenched route, successfully reduced bacterial viability of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa14,20. Moreover, silver-doped coacervates dry glasses have also shown antibacterial activity against S. aureus14. The antibacterial activity was mainly ascribed to the dissolution properties of phosphate-based glasses, which can release Ag+ ions in a sustainable way. It has to be noted that in this study, we consider the PC in gel form before calcination, and not in its glass state obtained after drying the coacervate gel.

Here we present, a series of silver-doped PC gels doped with various amounts of Ag+ (x = 0.1, 0.3 and 0.75 mol%). The antibacterial efficacy was tested by exposing bacteria commonly associated with wound infections, such as Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), Enterococcus faecalis (E. faecalis), Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) to the dissolution products of the PC in water and cell medium. For every microorganism, both non-AMR and AMR strains were used. The biocompatibility of silver-doped PC gels on human keratinocyte cells (HaCaT) in combination with bacteria was also investigated. This study is of particular interest given that there is still some controversy on the cytotoxicity of Ag+, particularly dependent on its concentration21,22.

Materials and methods

Synthesis

The following chemicals have been used without further purification; sodium polyphosphate (Na(PO3)n, Merck), calcium nitrate tetrahydrate (Ca(NO3)2·4H2O, Acros, 99.0%), and silver nitrate (AgNO3, Alfa Aesar, 99.9%). 20 mL of 2 M calcium nitrate tetrahydrate were slowly added to an equal volume of 4 M sodium polyphosphate using a syringe pump (20 mL h−1) under stirring for 1 h. Upon stirring, phase separation occurred in which an upper aqueous layer separated from a lower opaque coacervate layer. To prepare the 0.1, 0.3, 0.75 mol% Ag+ doped samples, 0.083,0.25 and 0.58 mL of a 2 M silver nitrate aqueous solution were added dropwise to the phase-separated mixture, respectively. After the addition of all reactants, the mixtures were stirred for a further hour and the samples were covered and allowed to settle overnight at room temperature. The top aqueous layer was then removed, and the bottom coacervate layer was transferred into a glass vial. Undoped coacervate gels will hereafter be named as PC and silver doped coacervate gels will be hereafter named as PC_AgX, where X is the mol% of Ag+.

Dissolution and pH studies

To assess the chemical species released upon dissolution, 10 mg of each coacervate gel were immersed in 10 mL of deionized water and left in the solution for 1, 3, 5, and 7 days. Three replicates for each condition (n = 3) were performed. The resulting suspensions for each time point were centrifuged at 4800 rpm for 10 min to separate the remaining coacervate gel from the solution. The pH upon dissolution of the gel PC was monitored both in water and cell medium at days 1, 3, 5 and 7 (Mettler Toledo SevenCompact™ pH meter).

Samples were filtered with a 0.45 µm unit (Millipore filter unit, Millex™-GP) followed by acidification with HNO3 (for Trace Metal Analysis from Fisher Chemical; final concentration 2% v/v HNO3) prior analysis by microwave plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (MP-AES, Agilent 4210). Calibration standards for P, Ca, Na and Ag were prepared from commercial solutions (SPEX CertiPrep™) in 2% v/v HNO3 and measured daily. The linear dynamic ranges and limits of detection (LOD, based on 3 × SD of the blank) were 0–10 ppm and 0.17 ppm, 0–6 ppm and 0.04 ppm, 0–10 ppm and 0.25 ppm, 0–100 ppm and 0.50 ppm, respectively for Na (at 588.95 nm), Ca (at 422.67 nm), P (at 213.618 nm) and Ag (at 546.549 nm). For Ca, Na and P measurements, samples required further 1:100 dilution in 2% HNO3, whereas a 1:1 dilution was sufficient for the measurement of Ag in the solubility samples.

Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy

FTIR spectra were collected using a Perkin Elmer spectrometer 2000-FTIR in the range of 4000–500 cm−1 with a resolution of 8 cm−1 (32 scans per sample).

Particle size and zeta potential measurement

A small quantity of each PC gel was dispersed in ultrapure water using ultrasonic agitation for 10 min to produce samples suitable for determining mean particle size and zeta potential of the polyphosphate clusters using dynamic light scattering (Malvern Zetasizer).

Antibacterial activity

The antibacterial activity of all coacervates was tested against a series of bacterial strains, both non-AMR and AMR, as listed in Table 1. All the strains were cultured in tryptic soy broth (TSB, Oxoid) at 37 °C with shaking at 250 rpm for 16–24 h. For bacterial strains carrying antibiotic-resistant plasmids, the necessary antibiotic concentration was added into TSB. 50 mg of each PC gel were added into 5 mL of the resulting bacterial TSB cultures and incubated at 37 °C under stirring at 250 rpm for 24 h. The undoped (silver-free) coacervate gel was used as a control. After the 24 h-incubation, a drop plate method was used for bacterial colony counting as previously described23. Briefly, samples were serially diluted (1:10 fold) under aseptic conditions, and 100 μL-aliquots from each dilution were spread on Tryptic Soya Agar (TSA) plates that were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The colonies formed on the plates were counted to calculate the Colony Forming Units per millilitre (CFU/mL) of the sample. The bacterial reduction was finally expressed as log10 CFU/mL with their corresponding error bars representing the standard deviation (two-way ANOVA for each time point). Asterisks illustrate the degree of statistical difference of the samples when compared to the control.

Cell viability studies

Cell viability was determined in the presence of the non-AMR bacterial strains indicated in Table 1. To analyse the toxicological effect of the PCs on skin cells, in vitro biocompatibility tests using HaCaT (human keratinocyte) cells from AddexBio were performed, as previously described15. The HaCaT cells were cultured in Eagle’s Essential Medium (ATCC) with 10% v/v fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Invitrogen) and 100 μg mL−1 of streptomycin (Thermofisher Scientific, UK) in a humidified incubator at 5% CO2 and 37 °C. Cells were routinely passaged on reaching approximately 80–90% of confluence. Simultaneously, 10 mg of each PC gel were immersed in 10 mL of deionised water and cell medium (1:1000) and orbitally incubated at 200 rpm for 24 h at 37 °C. Cells were then seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 5000–10,000 cells per well and incubated with medium overnight before adding 60 µL of the PC dissolution products obtained as described in section “Dissolution and pH studies”. HaCaT cells were challenged with the coacervate dissolution samples but in combination with bacterial cultures at a 1:1 ratio. Deionised water and cell medium were used as controls. After an incubation of 2 days, the media containing the dissolution products (or deionised water) were aspirated and 200 µL of fresh medium were added to each well to measure cell viability based on total mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity. This dehydrogenase activity was determined using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (Sigma-Aldrich). Briefly, 20 µL of a 1:1 MTT phosphate-buffered saline solution were added to each well and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 3 h. The liquid was aspirated from each well and replaced with 200 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich) to dissolve the insoluble purple formazan crystals formed within the cells due to the action of the mitochondrial dehydrogenase27. The absorbance of the DMSO solutions was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader (Fluostar-Omega, BMG LABTECH, Bucks, UK). Absorbance was then used to calculate the percentage of cell viability (%) as previously described28.

Antibacterial effect on human keratinocyte (HaCaT) cells

The antibacterial effect of PC gels was further determined in the presence of the non-AMR bacterial strains indicated in Table 1. HaCaT cells were challenged with the coacervate dissolution samples as described above, this time in presence of bacterial cultures (1:1 ratio). The 96-well plates were incubated in a BMG CLARIOStar multi-well plate reader at 5% CO2 and 37 °C, and following incubation bacterial growth was recorded based on the expression of absorbance at 600 nm and/or fluorescence emission at 515.20 nm. Fluorescence was only applied to samples containing bacteria expressing the Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP). HaCaT cells not exposed to any PC_Ag samples but exposed to bacteria were used as controls.

Results and discussion

A schematic illustrating the coacervate process for the synthesis of the PC gels and the studies performed in this work is presented in Fig. 1.

Synthesis

Sodium polyphosphate (NaPP), an inorganic solid formed by polyphosphate chains, is dissolved in water under stirring. After complete dissolution, a solution of Ca2+ is slowly added using a syringe pump (20 mL h−1) under constant stirring. Then an appropriate amount of Ag+ aqueous solution is added dropwise to the solution above and stirred for an hour to ensure homogenous mixing. Phase separation then occurs with the formation of a viscous liquid immiscible with water (coacervate, bottom layer) and a supernatant aqueous layer. The coacervate in contact with the supernatant layer is left to settle overnight at room temperature. After removal of the supernatant layer, a gel-like coacervate is obtained.

The PC gels have a high water content, and this makes them ideal materials for wound dressings as the moist environment prevents dehydration and facilitates the healing process. This study presents a series of 5 gel samples, containing 0.1, 0.3, 0.75 mol% Ag+. All gels were tested for dissolution and pH change in water and cell medium, antibacterial activity against a series of AMR and non-AMR strains and in vitro cytocompatibility studies, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Dissolution and pH studies

Dissolution studies were performed by immersing the PC gels in deionized water for up to 7 days. The solutions obtained after 1, 3, 5 and 7 days of immersion were then analysed to quantify the amount of P, Ca, Na and Ag released over time. The resulting dissolution profiles for P, Ca, Na and Ag are indicated in Fig. 2. We observed that, upon degradation, a gradual release of all ions occurs over time, and that most of the P, Ca and Na amounts are released in the first 24 h regardless of the Ag content (300–500 ppm P, 300 ppm Ca, 80–130 ppm Na and 0–30 ppm Ag). As expected, Ag+ release increases with the silver content.

In addition to the quantification of ions released in deionised water, the pH of the solutions containing the dissolution products was also measured after 1, 3, 5 and 7 days (Fig. 3). Since day 1, the pH of all deionised water solutions was significantly reduced from neutrality (pH ~ 7) to pH ~ 4 (Fig. 3A). After this significant drop, the pH remains relatively stable over the 7 days period, only decreasing slightly below 4. However, when the dissolution is performed in cell medium (Fig. 3B), the initial pH of ~ 8 decreased only slightly over the 7 days, remaining around neutrality (pH ~ 7).

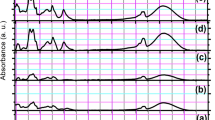

FT-IR spectroscopy

The structure of the phosphate gel network was investigated using FT-IR spectroscopy (Fig. 4). The vibrations observed are similar to those reported for dry glasses7. The absorption band near 1250 cm−1 is assigned to the asymmetric stretch in the PO2 metaphosphate units29, vas(PO2)−. The band near to 1100 cm−1 is assigned to the asymmetric stretching of chain-terminating PO3 groups30, νas(PO3)2−. The absorption band near 900 cm−1 is assigned to the asymmetric stretching modes of the P–O–P groups, νas(P–O–P)31. The peak at 540 cm−1 is attributed to O–P–O deformation modes31. The peaks at ~ 1600 cm−1 and 3400 cm−1 are assigned to the bending and stretching of O–H bonding in the residual water15. No significant differences were detected between the undoped gel and gels doped with different concentrations of silver.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis and zeta potential measurement

The average zeta potentials of the different PC gels were found to be between − 4 and − 9 mV with no clear trend exhibited between gels as the difference between samples was comparable to difference between measurements of individual samples. Due to the near-zero zeta potential the particles exhibited a strong tendency to agglomerate. This is as expected given the way in which the gels were manufactured in this study. Due to the tendency of the polyphosphate clusters to agglomerate all dispersions were very unstable and exhibited polydisperse particle size distribution making accurate determination of primary particle size impossible. PC, PC_Ag0.1 and PC_Ag0.3 all exhibited a distribution of particles centred around 130–350 nm. PC_Ag0.75 only exhibited a distribution centred around 1000–2000 nm, but this does not discount the possibility of smaller particles being present as the signal from the large particles is likely to have masked that from the smaller particles. Again, this is a consequence of the very poor stability of the suspension.

Antibacterial activity

All coacervate samples, undoped and doped with increasing concentrations of silver (0.1, 0.3, 0.75 mol% of Ag), were challenged against bacteria associated with wound infections (S. aureus, E. faecalis, E. coli and P. aeruginosa) (Fig. 5). For each sample, antibacterial tests were performed against two different strains, a non-AMR strain (Fig. 5, left) and a strain associated with AMR (Fig. 5, right). In all the experiments, three biological replicates and cultures with no coacervate gel were used as controls. The bacterial reduction was then determined after 24 h of incubation. Similarly to previous studies on phosphate-based glasses prepared by melt quenching and silicate-based glasses32,33, the undoped PC samples showed a small, but no significant, antibacterial activity.

Antibacterial activity of PC gels against non-AMR and AMR bacterial strains of S. aureus, E. faecalis, E. coli and P. aeruginosa. Bacterial reduction is expressed as the mean of CFU/mL ± standard deviation (error bars). Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA (**p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001; ****p ≤ 0.0001). Asterisks illustrate the degree of statistical difference of the samples when compared to the control.

The antibacterial activity displayed by the doped gels positively correlates with the Ag+ content; the antibacterial activity seems also dependent on the type of bacteria and whether the strains are resistant to antibiotics. In particular, the non-AMR strains are more tolerant than the AMR strains. When bacteria are challenged with PC_Ag0.1, we observed that the log reductions for the AMR strains are significantly higher than that recorded for non-AMR strains. When exposed to PC_Ag0.3 and PC_Ag0.75 the differences between the strains are not that evident and, in some cases, total inhibition is observed for both AMR and non-AMR strains. Another interesting observation is that the Gram-negative bacteria (E. coli and P. aeruginosa), either non-AMR or AMR strains, are more sensitive to the silver action than the Gram-positive bacteria (S. aureus and E. faecalis). Compared to the S. aureus and E. faecalis, the AMR strains of E. coli and P. aeruginosa were inhibited with all Ag+ concentrations, reaching the limit of detection point after 24 h (p ≤ 0.0001) with a log reduction of 6.8. Although the non-AMR strains of both E. coli and P. aeruginosa have shown slightly less sensitivity, by comparison with the AMR strains, significant log reductions (p ≤ 0.0001) of 6.5 were observed. For instance, PC_Ag0.1 sample reduced bacterial growth by 5 log (p ≤ 0.0001) and 6 log (p ≤ 0.0001) in the non-AMR resistant strains of E. coli and P. aeruginosa, respectively. With regards to the Gram-positive bacteria, S. aureus strains have proved to be more difficult to inhibit than strains of E. faecalis, with bacterial reductions ranging from 9.2 log for PC_Ag0.1 to 5.5 log (p ≤ 0.001) and 3.8 log (p ≤ 0.001) for PC_Ag0.3 and PC_Ag0.75, respectively.

The highest tolerance exhibited by Gram-positive bacteria (S. aureus and E. faecalis) could be attributed to their unique cell wall structure. It has been suggested that Gram-positive bacteria demonstrate a more resistive behaviour to metallic ions due to the thick peptidoglycan (PG) layer (~ 80 nm) in their cell walls, compared to the Gram-negative negatives (E. coli and P. aeruginosa), which are covered by a lipopolysaccharide layer (LPS) (~ 1–3 μm) and thinner peptidoglycan (1–3 nm)34. Moreover, the higher susceptibility of Gram-negative bacteria to metallic ions can be ascribed to the fact that the lipopolysaccharide layer is negatively charged35. The strong interaction between the lipopolysaccharide layer and the positively charged silver ions may facilitate higher ion uptake into the bacterial cell membrane, leading to intracellular damage34. Interestingly, AMR strains are shown as more sensitive to the Ag+ compared to the non-AMR. This could be attributed to the proactive use of pumps and multidrug transporters by the AMR strains. Multidrug transporters can induce resistance to antibiotics and also increase sensitivity, as shown for E.coli36. In particular, MacB and YbhFSR efflux transporters have been recently characterised as mediators to antibiotic resistance36,37.

A possible mechanism of action could start with the interaction between the positively charged silver ions and the negatively charged bacterial cell membrane. Upon the attachment, alterations on the cell membrane occur (i.e. membrane potential, viscoelasticity, phospholipid orientation)38. Such alternations modify the ionic diffusion rate and thus, stability of the proteins of the membrane which consequently would affect the membrane function. The interplay between the silver ions and bacterial membrane increase membrane permeability that causes membrane depolarization leading to cell death39,40. The structure of the bacterial cell wall and membrane (LPS) plays a major part in bacterial sensitivity to silver ions. However, other possible pathways have been proposed including the interaction of silver ions with sulfhydryl groups on the bacterial cell membrane that cause blockage of protein secretion and lipid biosynthesis41,42.

Cell viability study

The cytotoxicity of the dissolution products was assessed using HaCaT cells with the addition of non-AMR strains of S. aureus, E. faecalis E. coli and P. aeruginosa, as illustrated in Fig. 6. Only the non-AMR strains were considered given that these strains seem to be more tolerant to the PC_Ag dissolution products than the AMR strains. Regardless of the presence of bacteria, higher cytotoxicity was observed in water than in cell medium.

MTT analysis of HaCaT cells infected with bacteria in the presence of coacervate gels dissolution products in deionised water and cell medium. Error bars indicate the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA (*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001). Asterisks illustrate the degree of statistical difference when compared to the challenging sample.

Increasing concentrations of Ag+ trigger a negative effect on the viability of the challenged cells, especially when exposed to S. aureus and in water. The only exception is for the cells combined with E. coli since higher levels of silver resulted in a higher number of viable cells, with PC_Ag0.75 samples showing a significant increase (*p ≤ 0.05) in cell viability. In cell medium, the decrease in cell viability is only evident when using PC_Ag0.3 and PC_Ag0.75 samples. Bacteria seem to increase cell viability in combination with PC_Ag0 and PC_Ag0.1 samples, confirming no cytotoxic effects from low silver concentrations. Increasing silver concentrations normally results not only in higher bacterial inhibition14,43 but also in a more aggressive effect on the HaCaT cells, leading to high levels of toxicity.

These results show cytocompatibility of the dissolution products in both deionised water and cell medium. These observations are in agreement with previous studies reporting the protective role of silver on human keratinocytes44,45.

Antibacterial effect on human keratinocyte (HaCaT) cells

The antibacterial effect of PC gels was further tested against the non-AMR strains of S. aureus, E. faecalis, E. coli and P. aeruginosa when grown together with HaCaT cells (Fig. 7). Bacterial growth was measured based on absorbance (600 nm) for S. aureus and E. faecalis and fluorescent units for E. coli and P. aeruginosa. Therefore, changes in absorbance or fluorescent levels indicate fluctuation only in bacterial viability when compared to the control samples. HaCaT cells exposed only to bacteria (challenged), but not in contact with the dissolution products, were used as controls. As shown in Fig. 7, in absence of dissolution products (grey and black lines), the similarity was observed for a specific bacterium in both deionised water and cell medium, ruling out any interference from the growth environment. However, even in the absence of dissolution products, a difference was observed between different types of bacteria.

Except for S. aureus, PC gels dissolved in water show a significant antibacterial effect dependent on the silver content, especially against P. aeruginosa. It is worth noting that PC_Ag0.3 is the most effective sample against E. faecalis, while E. coli seems to be relatively sensitive to all doped PC samples. Interestingly, the presence of silver does not result in any additional effect against S. aureus since dissolution products with no silver can reduce bacterial growth down to the same levels observed with doped PC gels, either in water or cell medium. In the cell medium, a positive correlation between the silver content and the antibacterial activity against E. faecalis was also observed. However, neither undoped nor doped samples were capable of inhibiting E. coli and P. aeruginosa in cell medium, with no significant differences from the control. Results presented in Fig. 7, show that the two Gram-positive bacteria (S. aureus and E. faecalis) are much more sensitive to the PC_Ag gels that the Gram-negative (E. coli and P. aeruginosa), particularly in cell medium. These results are in agreement with a previous study that showed a 40% increase in the growth rate of Gram-negative bacteria in the presence of polyphosphates in solution if compared to the typical bacterial broth46.

Conclusions

A series of silver doped PC gels were prepared via coacervation in an aqueous solution at room temperature to test (a) their antibacterial activity against a series of bacteria commonly associated with wound infections and AMR (S. aureus, E. faecalis, E. coli and P. aeruginosa) and (b) their biocompatibility against HaCaT cells. Results have shown that the PC_Ag gels have a significant antibacterial effect that is dependent on the Ag+ concentration, the type of bacteria tested, the environmental growth conditions and the medium used to dissolve the gels. Dissolution tests have demonstrated a controlled, time-dependent release of silver ions. In addition, pH studies suggest that in cell medium the initial pH of ~ 8 decreases only slightly over the 7 days, remaining around neutrality (pH ~ 7). Furthermore, biocompatibility studies, suggest that PC_Ag, are not toxic for the HaCaT cells, both in the presence and in the absence of bacterial strains. In particular, PC_Ag0.1 seems to be the most promising sample given that can maintain good cell viability and simultaneously display antibacterial activity. These results show that gel-like silver doped coacervates are promising multifunctional materials being able to simultaneously induce soft tissue regeneration and controlled delivery of antibacterial ions.

References

Sen, C. K. Human wounds and its burden: An updated compendium of estimates. Adv. Wound Care 8, 39 (2019).

Frykberg, R. G. & Banks, J. Challenges in the treatment of chronic wounds. Adv. Wound Care 4, 560 (2015).

Piraino, F. & Selimović, Š. A current view of functional biomaterials for wound care, molecular and cellular therapies. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015 (2015).

Sorg, H., Tilkorn, D. J., Hager, S., Hauser, J. & Mirastschijski, U. Skin wound healing: An update on the current knowledge and concepts. Eur. Surg. Res. 58, 81–94 (2017).

Ventola, C. L. L. The antibiotic resistance crisis: Part 1: Causes and threats. Pharmacol. Ther. 40, 277 (2015).

Wound Care Market Worth $24.8 Billion by 2024. MarketsandMarkets 73–116 (2019)

Pickup, D. M. et al. Characterisation of phosphate coacervates for potential biomedical applications. J. Biomater. Appl. 28, 1226–1234 (2014).

Müller, W. E. G. et al. Enhancement of wound healing in normal and diabetic mice by topical application of amorphous polyphosphate. Superior effect of a host-guest composite material composed of collagen (host) and polyphosphate (guest). Polymers 9, 300 (2017).

Schepler, H. et al. Acceleration of chronic wound healing by bio-inorganic polyphosphate: In vitro studies and first clinical applications. Theranostics 27, 18–34 (2022).

Müller, W. E. G. et al. A new polyphosphate calcium material with morphogenetic activity. Mater. Lett. 148, 163–166 (2015).

Momeni, A. & Filiaggi, M. J. Comprehensive study of the chelation and coacervation of alkaline earth metals in the presence of sodium polyphosphate solution. Langmuir 30, 5256–5266 (2014).

Momeni, A. & Filiaggi, M. J. Degradation and hemostatic properties of polyphosphate coacervates. Acta Biomater. 41, 328–341 (2016).

Walbrou, O. et al. Iron polyphosphate coacervate. A new route for the treatment of inorganic wastes?. Phosphorus Res. Bull. 12, 211–218 (2001).

Kyffin, B. A. et al. Antibacterial silver-doped phosphate-based glasses prepared by coacervation. J. Mater. Chem. B 7, 7744–7755 (2019).

Foroutan, F. et al. Multifunctional phosphate-based glass fibres prepared via electrospinning of coacervate precursors: Controlled delivery, biocompatibility and antibacterial activity. Materialia 14, 100939 (2020).

Mouriño, V., Cattalini, J. P. & Boccaccini, A. R. Metallic ions as therapeutic agents in tissue engineering scaffolds: An overview of their biological applications and strategies for new developments. J. R. Soc. Interface 9, 401–419 (2012).

Sánchez-López, E. et al. Metal-based nanoparticles as antimicrobial agents: An overview. Nanomater. (Basel, Switzerland) 10, 292 (2020).

Hobman, J. L. & Crossman, L. C. Bacterial antimicrobial metal ion resistance. J. Med. Microbiol. 64, 471–497 (2015).

Turner, R. J. Metal-based antimicrobial strategies. Microb. Biotechnol. 10, 1062–1065 (2017).

Valappil, S. P., Knowles, J. C. & Wilson, M. Effect of silver-doped phosphate-based glasses on bacterial biofilm growth. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 5228–5230 (2008).

Nešporová, K. et al. Effects of wound dressings containing silver on skin and immune cells. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–14 (2020).

Garza-Cervantes, J. A. et al. Synergistic antimicrobial effects of silver/transition-metal combinatorial treatments. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–16 (2017).

Gutierrez, J., Barry-Ryan, C. & Bourke, P. Antimicrobial activity of plant essential oils using food model media: Efficacy, synergistic potential and interactions with food components. Food Microbiol. 26, 142–150 (2009).

Public Health England. Home (Public Health England, 2019).

Hoogenkamp, M. A., Crielaard, W. & Krom, B. P. Uses and limitations of green fluorescent protein as a viability marker in Enterococcus faecalis: An observational investigation. J. Microbiol. Methods 115, 57–63 (2015).

Microbial Sciences. Department of Plant and Microbial Sciences. University of Surrey (2021)

Riss, T. L. et al. Cell viability assays. Assay Guid. Man. (2016)

Alural, B., Ayyildiz, Z. O., Tufekci, K. U., Genc, S. & Genc, K. Erythropoietin promotes glioblastoma via miR-451 suppression. Vitam. Horm. 105, 249–271 (2017).

Uchino, T. & Yoko, T. Structure and vibrational properties of alkali phosphate glasses from ab initio molecular orbital calculations. J. Non Cryst. Solids 263–264, 180–188 (2000).

Byun, J. O. et al. Properties and structure of RO-Na2O-Al2O3-P2O5 (R = Mg, Ca, Sr, Ba) glasses. J. Non Cryst. Solids 190, 288–295 (1995).

Hudgens, J. J. & Martin, S. W. Glass transition and infrared spectra of low-alkali, anhydrous lithium phosphate glasses. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 76, 1691–1696 (1993).

Valappil, S. P. et al. Antimicrobial gallium-doped phosphate-based glasses. Adv. Funct. Mater. 18, 732–741 (2008).

Begum, S., Johnson, W. E., Worthington, T. & Martin, R. A. The influence of pH and fluid dynamics on the antibacterial efficacy of 45S5 Bioglass. Biomed. Mater. 11, 015006 (2016).

Slavin, Y. N., Asnis, J., Hafeli, U. O. & Bach, H. Metal nanoparticles: Understanding the mechanisms behind antibacterial activity. J. Nanobiotechnol. 15, 1–20 (2017).

Yang, Y., Bechtold, T., Redl, B., Caven, B. & Hu, H. A novel silver-containing absorbent wound dressing based on spacer fabric. J. Mater. Chem. B 5, 6786–6793 (2017).

Greene, N. P., Kaplan, E., Crow, A. & Koronakis, V. Antibiotic resistance mediated by the MacB ABC transporter family: A structural and functional perspective. Front. Microbiol. 9, 950 (2018).

Feng, Z. et al. A putative efflux transporter of the ABC family, YbhFSR, in Escherichia coli functions in tetracycline efflux and Na+(Li+)/H+ transport. Front. Microbiol. 11, 556 (2020).

Godoy-Gallardo, M. et al. Antibacterial approaches in tissue engineering using metal ions and nanoparticles: From mechanisms to applications. Bioact. Mater. 6, 4470–4490 (2021).

Abbaszadegan, A. et al. The effect of charge at the surface of silver nanoparticles on antimicrobial activity against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria: A preliminary study. J. Nanomater. 2015 (2015)

Gomaa, E. Z. Silver nanoparticles as an antimicrobial agent: A case study on Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli as models for Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 63, 36–43 (2017).

Bondarenko, O. M. et al. Plasma membrane is the target of rapid antibacterial action of silver nanoparticles in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Nanomed. 13, 6779–6790 (2018).

Gordon, O. et al. Silver coordination polymers for prevention of implant infection: Thiol interaction, impact on respiratory chain enzymes, and hydroxyl radical induction. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 4208–4218 (2010).

Park, H. J. et al. Silver-ion-mediated reactive oxygen species generation affecting bactericidal activity. Water Res. 43, 1027–1032 (2009).

Arora, S. et al. Silver nanoparticles protect human keratinocytes against UVB radiation-induced DNA damage and apoptosis: Potential for prevention of skin carcinogenesis. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 11, 1265–1275 (2015).

Pillay, V. et al. A review of the effect of processing variables on the fabrication of electrospun nanofibers for drug delivery applications. J. Nanomater. 2013 (2013).

Lorencová, E., Vltavská, P., Budinský, P. & Koutný, M. Antibacterial effect of phosphates and polyphosphates with different chain length. J. Environ. Sci. Health A Toxicol. Hazard. Subst. Environ. Eng. 47, 2241–2245 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Doctoral College, the University of Surrey and Fourth State Medicine Ltd for funding AN PhD studentship; EPSRC (grant EP/P033636/1) and Royal Society (grant RSG/R1/180191) for providing the funding to conduct this study. The authors are also grateful to the Department of Microbial and Cellular Sciences, the University of Surrey for providing E. coli K12 and P. aeruginosa PAO1 strains and to Dr. Ing. Hoogenkamp, Academic Centre for Dentistry Amsterdam (ACTA), and VU Department of Preventive Dentistry, the University of Amsterdam for providing the E. faecalis OG1RF strain. Finally, the authors would like to thank Dr Elliot, School of Biosciences and Medicine, University of Surrey, for his help with cell studies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.N. Data collection/analysis and interpretation, draft of the article. M.F.S. Contribution to ICP data collection/analysis. D.C./J.G.-M. Design of the work, critical revision of the article. R.D. Zeta potential and DLS.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nikolaou, A., Felipe-Sotelo, M., Dorey, R. et al. Silver-doped phosphate coacervates to inhibit pathogenic bacteria associated with wound infections: an in vitro study. Sci Rep 12, 10778 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-13375-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-13375-y

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.