Abstract

Kikuchi–Fujimoto disease (KFD) is a rare benign and self-limiting syndrome. We aim to review cases of KFD at our institution as a rare illness in the Arab ethnic descent and to analyse reports from most countries in the East Mediterranean zone. This is a retrospective study in which the histopathology database was searched for the diagnosis of KFD. A full review of KFD patients’ medical records was done. Data regarding demographic features, clinical presentation, laboratory findings, comorbidities, and management protocols were obtained. Published KFD cases from east Mediterranean countries were discussed and compared to other parts of the world. Out of 1968 lymph node biopsies studied, 11 (0.6%) cases of KFD were identified. The mean age of patients with KFD was 32 years (4–59). 73% (8/11) were females. The disease was self-limiting in 5 patients (45%); corticosteroid therapy was needed in 4 patients (34%). One patient was treated with methotrexate and one with antibiotics. One patient died as a consequence of lymphoma. Jordanians and Mediterranean populations, especially those of Arab ethnic background, seem to have low rates of KFD. The genetic susceptibility theory may help to explain the significantly higher disease prevalence among East Asians. Early diagnosis of KFD—although challenging—is essential to reduce the morbidity related to this illness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Kikuchi–Fujimoto disease (KFD), which is also known as histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis, is a rare cause of lymphadenopathy1, that was first recorded in Japan in 1972 by Kikuchi and Fujimoto2,3. It is an extremely rare benign, self-limited disease. The condition is also characterized by fever, night sweats, fatigue and to a lesser extent skin rash and joint pain4. The exact cause of KFD is still obscure. However, the acute clinical course, febrile self-limited nature, as well as the histologic changes associated with this illness, all support the theory of immune response to an infectious etiology, primarily viral agents, such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human herpesviruses 6 and 8, HIV, parvovirus B195,6,7, and Torque teno/torque teno-like minivirus (TTV/TTMV), which closely resembles the circovirus that causes necrotizing lymphadenitis in pigs. TTV/TTMV presence in patients with KFD has been confirmed with successful amplification and DNA sequencing8,9.

Kikuchi and Fujimoto originally identified this pathology among Japanese and other Asiatic women; the condition has since been defined worldwide in both genders and in a variety of ethnic backgrounds, with higher prevalence among females10. From our region (middle-east/Arabic countries), there are few scattered reports of KFD that have been published over the last 20–30 years.

In this retrospective study, we aim to review and summarize previous reports of KFD in the east Mediterranean countries and to describe the incidence as well as the characteristics of KFD among Jordanians as a Mediterranean population of Arab ethnic background. We assessed KFD in terms of clinical, laboratory and epidemiological features. Comorbid illnesses, treatment protocols and clinical outcomes were analyzed as well. To our knowledge, this is the largest descriptive analysis of KFD in Jordan.

Results

Between 2006 and 2021, 1968 lymph node biopsies were submitted to our histopathology laboratory. Eleven cases (0.6%) had the diagnosis of KFD. Mean age of patients with KFD was 32 years (4–59). 73% (8/11) were females.

Fatigue (82%), appetite loss (81%) and fever (63%) were the most frequent presenting symptoms. On physical examination, Lymphadenopathy was the most common finding (11/11) followed by arthritis (4/11) and hepatosplenomegaly (2/11). 82% (9/11) of the patients had cervical lymphadenopathy while only 18% (2/11) had axillary lymphadenopathy. (Table 1).

37 reports of KFD in the East Mediterranean zone were retrieved, with a total of 95 patients. 15 reports (60 patients) were from Arabic countries. Lymphadenopathy (in 32/37 studies) and fever (in 20/37 studies) were the main presenting symptoms, whereas fatigue and joint pain were only occasionally reported (in 4/37 and 1/37 reports, respectively). In fact, these findings apply to both Arab and non-Arab Mediterranean countries included in Table 2.

When compared to other ethnic groups, tender lymphadenitis (50%) and fever (43%) were, similarly; the most frequent clinical findings in studies from East Asia (Taiwan) and China4,11,12, while Joint pain and hepatosplenomegaly were much less encountered in the Asian ethnicity. Reports from western countries, which may still include up to 20% of patients from Asian backgrounds13, also showed that lymphadenopathy and fever represent the classic hallmarks of the disease3.

Some of our patients from Jordan had other comorbidities including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and chronic kidney disease (1/11), B cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (1/11), epilepsy (1/11), migraine headache (1/11) and cystic hygroma (1/11). (Table 1).

In Laboratory work up, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation (ESR) rate (72%) (Range of abnormal findings: 27-more than 100, normal reference Values: 0–20), leukocytosis (63%) (Range of abnormal readings: 11.5 × 103–17 × 103, normal reference values: 4–11 × 103) and elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (54%) (Range of abnormal readings: 282–1789, normal reference values: 240–480) were the most common findings. (Table 1).

Most of our patients had self-regression of the disease without any targeted treatment (5/11) (45%). Treatment with oral corticosteroids was attempted in 4 (34%) patients (prednisolone dosage 0.5 mg/kg per day, duration range: 2 weeks–9 months). All corticosteroids’ therapy group recovered completely without relapse. Oral antibiotics (Amoxicillin and clavulanate potassium; Beta-lactamase inhibitor) were prescribed in two cases, as well.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the prevalence rate of KFD among Jordanian patients who underwent lymph node biopsy at our center. Our results showed that out of each thousand lymph node biopsies, 6 were diagnosed with KFD (0.6%), which is a comparable rate to others reported in non-Asian communities.

Mediterranean populations of Arab ethnic background seem to have similar rates. Reported numbers from the gulf region might be slightly affected by non-Arab ethnicities included in the studies. In Kuwait14, between 2005 and 2009, a study reviewed 2,369 fine needle aspirations (FNA) of patients with lymphadenopathy. Of these, 76 (3.2%) patients were diagnosed with KFD or were suggestive of KFD, 51 of the 76 (67%) KFD patients were non-Kuwaiti, primarily from the Indian Subcontinent and South-East Asia. In Saudi Arabia, a study included 2500 lymph node biopsies, revealed KFD in only 15 (0.6%) patients15. Another report from Saudi Arabia by Kutty MK et al. recognized only 5 cases of KFD in 920 lymph node biopsies (0.5%)16.

A-14-patient case series from Qatar by Al Soub et al.17, represented a KFD incidence rate of approximately 1.6% from 900 lymph node biopsies; Almost half (43%) of KFD cases in this series were of non-Qatari nationalities.

Similarly, large data from other Mediterranean ethnicities such as Turki4, Iranian18, and Greek19, are still lacking. The published small-volume reports may indicate low incidence rate. In addition, review of these reports revealed clinical characteristics that correspond with data from other Mediterranean populations. Table 2 summarizes the main reports of KFD from Eastern Mediterranean countries.

Studies from Asia disclosed 10–40 times higher incidence rates of KFD, especially among female patients with cervical lymphadenopathy, which seemed to be the main presenting sign. In a retrospective study of 147 Korean patients who had enlarged (≥ 1 cm in diameter) cervical lymph nodes for a duration > 1 week, 51 (34.7%) had KFD. All patients in this study had core needle biopsies obtained under ultrasound guidance11. In their analysis of published literature, Kucukardali and colleagues showed that nearly 50% (166/330) of reported KFD cases between 1991 and 2005 originated in East Asia and the Far-East, with about 36% being from Taiwan, which had the majority of reported cases4.

There is no clear explanation for the lower incidence of KFD among Arab and other non-Asian ethnicities. However, some studies raised the theory of genetic susceptibility that makes east-Asians at higher risk to become affected. In one study by Tanaka and colleagues20, they performed DNA typing of human leukocyte antigens (HLA) class II genes (HLA-DR, -DQ, and -DP), and found that frequencies of DPA1*01 and DPB1*0202 allele in HLA class II genes were significantly higher among KFD patients; this allele is relatively frequent in Asians (e.g., Korean 9.9%, Japanese 4.5%) when compared to Caucasians (e.g., French 0.4%, Italian 0.8%), and Arabs (Lebanese 2.97%21)22,23. It is also unclear if environmental triggers play a role in the pathogenesis of this illness.

Although KFD is considered a benign condition, the significant morbidity with frequent hospitalization may be attributed to mistaken diagnosis with other lymphoproliferative disorders, connective tissue diseases or infectious etiologies. Multiple other factors may also contribute to the increased morbidity of KFD; these include either disease-linked complications or concurrent other systemic illnesses. Complications that have been described varied from potentially fatal manifestations, such as disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC)24,25, abrupt heart failure, KFD-triggered hemaphagocytic syndrome, and polymyositis with respiratory failure26,27,28, to less extensive and regional implications similar to lymphedema and cutaneous eruption29,30. Moreover, some reports described the occurrence of other conditions simultaneously with KFD, such as Hashimoto thyroiditis31,32, aseptic meningitis (only 4 cases reported)33,34 and Still’s disease35; these may contribute to the increased morbidity of the disease.

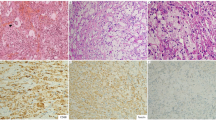

The diagnosis of KFD is challenging. It relies on a combination of clinical and histopathologic features. Histologically, the disease is evaluating in different stages represented by three subtypes; the early proliferative type, the necrotizing type and the xanthomatous type. The necrotizing type is the most common and characterized by the presence of non-neutrophilic necrotizing foci surrounded by mononuclear cells and show abundant karyorrhectic debris. The early type is characterized by the presence of predominant immunoblastic paracortical infiltrate admixed with histiocytes. The healing phase of KFD is mostly represented by the presence of foamy histiocytes and referred to as xanthomatous type36,37.

Cases with abundant immunoblastic proliferation may be mistaken for high grade lymphoma. However, the presence of abundant histiocytic infiltrate, lack of complete lymph node effacement by B-lymphocytes Immunohistochemical markers and loss of clonality proof by B-surface immunoglobulin arrangement and T-cell receptor gene rearrangement, both favour the diagnosis of KFD36.

The mechanism by which KFD is linked to other autoimmune diseases remains unknown. Some researchers hypothesized that KFD was a T-cell mediated response to antigen stimuli in genetically susceptible individuals based on immunostains and histological findings3.

Affected patients with KFD may need to be followed for years due to the possibility of association with systemic lupus erythematosus. In addition, recurrences of Kikuchi disease can occasionally continue for many years38. Early detection and treatment of KFD to control active inflammation is crucial, owing to the presumptive reduction in the risk of consequent limb swelling and permanent lymphedema.

KFD is nominated as a self-limiting disease in the majority of cases. However, supportive treatment, with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (sDIASN) is used for many patients to alleviate associated symptoms, such as fever, lymphadenitis-induced pain or arthralgia. Since etiology of this disease is still uncertain, definitive treatment remains challenging. In multiple studies corticosteroids were used for severe forms of disease (not responding to NSAIDS, prolonged course), relapsing lymphadenitis, or in patients with KFD manifestations (as listed above)39. Other reports described successful use of hydroxychloroquine and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) for intractable disease38,40.

Our study has some limitations. First, it is a retrospective study. Second, the sample size of patients with KFD was relatively small to evaluate risk factors with statistical significance. In spite of these limitations, findings in this study should expand awareness of KFD, contribute to better understanding of clinical behaviour of this illness and highlight the importance of formulating a solid consensus regarding diagnosis and treatment protocols.

In conclusion, KFD may still be under-diagnosed in our part of the world, likely due to the non-specific mixed symptoms at presentation as well as to the lack of awareness among general practitioners and health care providers. Early diagnosis with tissue biopsy and treatment is essential to reduce associated morbidity.

Materials and methods

Study design

This is a retrospective study in which we identified patients diagnosed with KFD between January 2002 and January 2021. All patients included were diagnosed at King Abdullah University Hospital (KAUH). Jordan. The histopathology department’s database was searched for KFD during this period. Biopsies were collected locally at KAUH and at affiliated hospitals, and then submitted to KAUH. Full review of patients’ medical records was done. Patients were also contacted for follow up and verification whenever necessary. Data regarding demographic features, clinical presentation, laboratory findings, comorbidities and management protocols were obtained.

Work up for lymphadenopathy was driven by clinical evaluation. The following investigations were obtained as needed: complete blood count (CBC) and peripheral blood smear, Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), Kidney function test, Liver function test and urine analysis, ESR and CRP. Screening for TB (sputum for Acid-Fast Bacillus (AFB), PPD testing), HIV (human immunodeficiency virus), and specific titers for Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Toxoplasma species were rarely considered because patients presented almost always with regional lymph node enlargement.

Imaging studies included chest radiography, computerized tomographic (CT) scan for chest and/or abdomen, abdominal and cervical ultrasonography.

To retrieve reports of KFD in the Eastern Mediterranean region, the keywords (KFD, necrotizing lymphadenitis, histiocytic, Mediterranean, Middle East, Arab, and the individual name of each of the listed states in Table 1, were searched through PubMed or Medline, Embase Scopus, and Ovid databases. Full texts of the studies were obtained and year of publication, number of cases, main presenting symptoms were recorded.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS v.20.0 (Chicago, IL, USA) software was used for statistical analysis.

Inclusion criteria

All adult or pediatric Jordanian patients with biopsy proven KFD disease, who were diagnosed at King Abdullah university hospital, and affiliated centers, were included.

Ethics and confidentiality

The study was assessed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at King Abdullah University Hospital and by the Committee of Research on Human Subjects at the Jordan University of Science and Technology. (Non-funded Research Grant No: 20210141). We protected Patients’ confidentiality in accordance with declaration of Helsinki provisions. Informed consent was waived by the ethics Institutional Review Board at King Abdullah University Hospital and by the Committee of Research on Human Subjects at the Jordan University of Science and Technology that approved our study Procedures.

For tissue diagnosis, most patients (10/11) in this series had open lymph node biopsy. Only one patient underwent ultrasound guided Tru-Cut® axillary lymph node biopsy.

Histopathology

Lymph node biopsies were analyzed and reported by hematopatholohist. The histologic diagnosis of KFD was defined based on the presence of patchy areas of paracortical non-suppurative necrosis with the presence of abundant karyorrhectic debris. The necrotic areas are surrounded by mononuclear cells predominantly histiocytes including crescentic histiocytes. (Fig. 1).

Immunohistochemical studies including CD20, CD3, Cd4, CD8, and CD68 were performed on selected cases whenever indicated.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

28 April 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-11109-8

References

Gaddey, H. L. & Riegel, A. M. Unexplained lymphadenopathy: Evaluation and differential diagnosis. Am. Fam. Phys. 94(11), 896–903 (2016).

Kikuchi, M. Lymphadenitis showing focal reticulum cell hyperplasia with nuclear debris and phagocytosis. J. Jpn. Hist. Med. 35, 379–438 (1972).

Bosch, X., Guilabert, A., Miquel, R. & Campo, E. Enigmatic Kikuchi–Fujimoto disease: A comprehensive review. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 122(1), 141–152. https://doi.org/10.1309/YF08-1L4T-KYWV-YVPQ (2004).

Kucukardali, Y. et al. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: Analysis of 244 cases. Clin. Rheumatol. 26(1), 50–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-006-0230-5 (2007).

Hudnall, S. D., Chen, T., Amr, S., Young, K. H. & Henry, K. Detection of human herpesvirus DNA in Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease and reactive lymphoid hyperplasia. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 1(4), 362–368 (2008).

Yufu, Y. et al. Parvovirus B19-associated haemophagocytic syndrome with lymphadenopathy resembling histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis (Kikuchi’s disease). Br. J. Haematol. 96, 868–871. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.d01-2099.x (1997).

Chong, Y., Kang, CS. Causative agents of Kikuchi–Fujimoto disease (histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis): A meta-analysis. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 78(11), 1890–1897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2014.08.019 (2014).

Chong, Y., Lee, J., Kang, C., & Lee, E.: Identification of torque teno virus/torque teno-like minivirus in the cervical lymph nodes of kikuchi-fujimoto lymphadenitis patients (Histiocytic Necrotizing Lymphadenitis): A possible key to idiopathic disease. Biomed. Hub. 5, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1159/000506501 (2020).

Chong, Y., Lee, J. Y., Thakur, N., Kang, C. S. & Lee, E. J. Strong association of Torque teno virus/Torque teno-like minivirus to Kikuchi-Fujimoto lymphadenitis (histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis) on quantitative analysis. Clin. Rheumatol. 39(3), 925–931. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04851-4 (2020).

Hutchinson, C. B. & Wang, E. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 134(2), 289–293. https://doi.org/10.5858/134.2.289 (2010).

Song, J. Y. et al. Disease spectrum of cervical lymphadenitis: analysis based on ultrasound-guided core-needle gun biopsy. J. Infect. 55(4), 310–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2007.06.004 (2007).

Lin, H.-C., Su, C.-Y., Huang, C.-C., Hwang, C.-F. & Chien, C.-Y. Kikuchi’s disease: A review and analysis of 61 cases. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 128(5), 650–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0194-59980223291-X (2003).

Deaver, D., Naghashpour, M., Sokol, L. Kikuchi-fujimoto disease in the United States: three case reports and review of the literature [corrected] [published correction appears in Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 6(1):E2014023]. Mediterr. J. Hematol. Infect. Dis. 6(1):e2014001. https://doi.org/10.4084/MJHID.2014.001 (2014).

Das, D. K. et al. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease in fine-needle aspiration smears: A clinico-cytologic study of 76 cases of KFD and 684 cases of reactive hyperplasia of the lymph node. Diagn. Cytopathol. 41(4), 288–295. https://doi.org/10.1002/dc.21810 (2013).

Al-Maghrabi, J. & Kanaan, H. Histiocytic necrotising lymphadenitis (Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease) in Saudi Arabia: Clinicopathology and immunohistochemistry. Ann. Saudi Med. 25(4), 319–323. https://doi.org/10.5144/0256-4947.2005.319 (2005).

Kutty, M. K., Anim, J. T. & Sowayan, S. Histiocytic necrotising lymphadenitis (Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease) in Saudi Arabia. Trop. Geogr. Med. 43(1–2), 68–75 (1991).

Al Soub, H., Al Bosom, I., El Deeb, Y., Al Maslamani, M. & Al KHuwaiter J,. Histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis (Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease): A study of 14 cases from Qatar. Qatar Med. J 15, 24–28. https://doi.org/10.5339/qmj.2006.2.13 (2006).

Baziboroun, M., Bayani, M., Kamrani, G., Saeedi, S. & Sharbatdaran, M. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease in an Iranian woman: a rare but important cause of lymphadenopathy. Arch. Emerg. Med. 7(1), 3 (2019).

Vassilakopoulos, T. P. et al. Kikuchi’s lymphadenopathy: A relatively rare but important cause of lym-phadenopathy in Greece, potentially associated with the antiphospholipid syndrome. Rheumatol. Int 30(7), 925–932. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-009-1077-2 (2009).

Tanaka, T. et al. DNA typing of HLA class II genes (HLA-DR, -DQ and -DP) in Japanese patients with histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis (Kikuchi’s disease). Tissue Antigens 54(3), 246–253 (1999).

Haddad, J., Shammaa, D., Abbas, F. & Mahfouz, R. A. First report on HLA-DPA1 gene allelic distribution in the general Lebanese population. Meta. Gene. 8, 11–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mgene.2016.01.004 (2016).

Hajjej, A., Almawi, W. Y., Arnaiz-Villena, A., Hattab, L. & Hmida, S. The genetic heterogeneity of Arab populations as inferred from HLA genes. PLoS ONE 13(3), e0192269 (2018).

Sánchez-Velasco, P. & Karadsheh, N. S. Molecular analysis of HLA allelic frequencies and haplotypes in Jordanians and comparison with other related populations. Hum. Immunol. 62, 901–909 (2001).

Barbat, B., Jhaj, R. & Khurram, D. Fatality in Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: A rare phenomenon. World J. Clin. Cases 5(2), 35–39. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v5.i2.35 (2017).

Uslu, E. et al. Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy caused by Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease resulting in death: First case report in Turkey. Int. Med. Case Rep. J. 7, 19–22. https://doi.org/10.2147/IMCRJ.S58891 (2014).

Sharma, V. & Rankin, R. Fatal Kikuchi-like lymphadenitis associated with connective tissue disease: A report of two cases and review of the literature. Springerplus 4, 167. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-015-0925-7 (2015).

Duan, W., Xiao, Z. H., Yang, L. G. & Luo, H. Y. Kikuchi’s disease with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: A case report and literature review. Medicine 99(51), e23500. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000023500 (2020).

Wilkinson, C. E. & Nichol, F. Kikuchi–Fujimoto disease associated with polymyositis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 39(11), 1302–1304. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/39.11.1302 (2000).

Kim, J. H., Kim, Y. B., In, S. I., Kim, Y. C. & Han, J. H. The cutaneous lesions of Kikuchi’s disease: A comprehensive analysis of 16 cases based on the clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and immunofluorescence studies with an emphasis on the differential diagnosis. Hum. Pathol. 41(9), 1245–1254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2010.02.002 (2010).

Han, K., Go, J., Myong, N. & Lee, W. Fine needle aspiration cytology of Kikuchi’s lymphadenitis: With emphasis on differential diagnosis with tuberculosis. Korean. J. Pathol. 45, 626. https://doi.org/10.4132/KoreanJPathol.2011.45.6.626 (2011).

Lee, E. J., Lee, H. S., Park, J. E. & Hwang, J. S. Association Kikuchi disease with Hashimoto thyroiditis: A case report and literature review. Ann. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 23(2), 99–102. https://doi.org/10.6065/apem.2018.23.2.99 (2018).

Go, E. J., Jung, Y. J., Han, S. B., Suh, B. K. & Kang, J. H. A case of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease with autoimmune thyroiditis. Korean J. Pediatr. 55(11), 445–448. https://doi.org/10.3345/kjp.2012.55.11.445 (2012).

Komagamine, T. et al. Recurrent aseptic meningitis in association with Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: Case report and literature review. BMC Neurol. 12(1), 112. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-12-112 (2012).

Yang, H. D., Lee, S. I., Son, I. H. & Suk, S. H. Aseptic meningitis in Kikuchi’s disease. J Clin. Neurol. 1(1), 104–106. https://doi.org/10.3988/jcn.2005.1.1.104 (2005).

Toribio, K. A., Kamino, H., Hu, S., Pomeranz, M. & Pillinger, M. H. Co-occurrence of Kikuchi-Fujimoto’s disease and Still’s disease: Case report and review of previously reported cases. Clin. Rheumatol. 34(12), 2147–2153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-014-2755-3 (2015).

Perry, A. M. & Choi, S. M. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: A review. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 142(11), 1341–1346. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2018-0219-RA (2018).

Choi, J. W., Lee, J. H., Lee, J. H., Chae, Y. S. & Kim, I. The clinicopathologic analysis of Kikuchi’s lymphadenitis. Korean. J. Pathol. 38(5), 289–294 (2004).

Honda, F. et al. Recurrent Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease successfully treated by the concomitant use of hydroxychloroquine and corticosteroids. Intern. Med. 56(24), 3373–3377. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.9205-17 (2017).

Yalcin, S. et al. Management of Kikuchi–Fujimoto disease using glucocorticoid: a case report. Clin. Med. Case Rep. 2011, 230840. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/230840 (2011).

Noursadeghi, M., Aqel, N., Gibson, P. & Pasvol, G. Successful treatment of severe Kikuchi’s disease with intravenous immunoglobulin. Rheumatology (Oxford) 45(2), 235–237. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kei074 (2006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.R.A.: idea, design of the work, interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript, revising the manuscript. H.A.: design of the work, acquisition of data, drafting the manuscript, analysis of the data. M.A.A.: acquisition of data, interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript. D.A.: acquisition of data, interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript, revising the manuscript. M.S.: acquisition of data, interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript. S.A.: acquisition of data, interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript, revising the manuscript. J.F.: acquisition of data, interpretation of data, revising the manuscript. R.A.: acquisition of data, drafting the manuscript, revising the manuscript. M.N.: acquisition of data, drafting the manuscript, revising the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in Affiliations 3 and 4, which were incorrectly given as ‘Department of Radiology, Faculty of Medicine, Hashemite University, Zarqa, Jordan’ and ‘Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Hashemite University, Zarqa, Jordan’. The correct affiliations are: ‘Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, The Hashemite University, Zarqa, Jordan’ and ‘Department of Radiology, Faculty of Medicine, The Hashemite University, Zarqa, Jordan’.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al Manasra, A.R., Al-Domaidat, H., Aideh, M.A. et al. Kikuchi–Fujimoto disease in the Eastern Mediterranean zone. Sci Rep 12, 2703 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-06757-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-06757-9

This article is cited by

-

The mysterious anelloviruses: investigating its role in human diseases

BMC Microbiology (2024)

-

Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome masquerading as a lymphoproliferative disorder in a young adult on immunosuppressive therapy for rheumatoid arthritis: a case report

Journal of Medical Case Reports (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.