Abstract

Surveillance data from Southern Ontario show that a majority of Verona Integron-encoded Metallo-β-lactamase (VIM)-producing Enterobacteriaceae are locally acquired. To better understand the local epidemiology, we analysed clinical and environmental blaVIM-positive Enterobacteriaceae from the area. Clinical samples were collected within the Toronto Invasive Bacterial Diseases Network (2010–2016); environmental water samples were collected in 2015. We gathered patient information on place of residence and hospital admissions prior to the diagnosis. Patients with and without plausible source of acquisition were compared regarding risk exposures. Microbiological isolates underwent whole-genome sequencing (WGS); blaVIM carrying plasmids were characterized. We identified 15 patients, thereof 11 with blaVIM-1-positive Enterobacter hormaechei within two genetic clusters based on WGS. Whereas no obvious epidemiologic link was identified among cluster I patients, those in cluster II were connected to a hospital outbreak. Except for patients with probable acquisition abroad, we did not identify any further risk exposures. Two blaVIM-1-positive E. hormaechei from environmental waters matched with the clinical clusters; plasmid sequencing suggested a common ancestor plasmid for the two clusters. These data show that both clonal spread and horizontal gene transfer are drivers of the dissemination of blaVIM-1-carrying Enterobacter hormaechei in hospitals and the aquatic environment in Southern Ontario, Canada.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global dissemination of metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs) constitutes a severe threat to modern healthcare. MBLs exhibit a broad hydrolytic spectrum, which inactivates many currently used β-lactams. The Verona Integron-encoded Metallo-β-lactamase (VIM) is among the most common MBLs causing human infection1. Over the last decade this carbapenemase has become a serious health threat in healthcare institutions in countries such as Greece, Italy, and Spain2,3,4. It has been associated with outbreaks of hospital acquired infections due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacteriaceae, and has been found in both sewage and surface water in many countries5,6,7,8,9,10. The successful dissemination of the blaVIM-gene can be explained by its location on gene cassettes of class 1 integrons which themselves are usually found on mobile genetic elements such as transposons and plasmids1,11.

In North America, VIM-producing Enterobacteriaceae have been found in numerous geographic areas but are less common than carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) carrying other carbapenemases12,13,14,15. In southern Ontario, population-based surveillance from 2007 to 2015 showed that the New Delhi Metallo-β-lactamase (NDM) and the Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase (KPC) were the most commonly detected carbapenemases (56% and 25%, respectively), whereas the VIM carbapenemase only accounted for 5% of cases. In contrast to patients with other CPE, two-thirds of patients with blaVIM-positive Enterobacteriaceae did not have a history of hospital admission or travel abroad, suggesting local acquisition16. This prompted us to study the molecular epidemiology of clinical VIM isolates, to compare these to environmental water isolates from our area, and to search for risk factors for VIM acquisition.

Results

Clinical and environmental isolates

Between 2007 and January 2016, Toronto Invasive Bacterial Diseases Network (TIBDN) surveillance identified 300 patients colonized or infected with CPE, thereof 15 unique patients (5%) colonized or infected by 16 non-duplicate blaVIM-positive Enterobacteriaceae. Eleven patients carried E. cloacae complex isolates, one patient each carried E. coli, Citrobacter freundii, and Klebsiella pneumoniae and one patient carried both C. freundii and K. pneumoniae. All isolates were positive for blaVIM-1, except for one C. freundii carrying blaVIM-2. Two patients were co-colonized with other CPEs: one with an NDM-producing E. coli and an NDM/OXA-48 co-producing K. pneumoniae, and one with an NDM-producing K. pneumoniae. Environmental water sampling in 2015 detected four blaVIM-1-positive isolates belonging to the E. cloacae complex, three from surface water (1 site) and one from sewage water (1 site). After submission, the whole genome sequences (WGS) of all fifteen of the E. cloacae complex isolates were 98.412% to 99.928% identical by average nucleotide identity to the type genome of E. hormaechei, with 75.6% to 89.4% coverage of the genome, according to NCBI analysis using average nucleotide identity (ANI) and comparing the submitted genome sequences against the genomes of the type strains that are already in GenBank. Therefore, we are using E. hormaechei as the organism name for these isolates.

MLST and SNP analysis

SNP analysis showed two patient clusters among E. hormaechei. The four patients with isolates comprising cluster I were identified between 2010 and 2012 (10 to 106 SNPs, all ST93). The six patients with isolates comprising cluster II were identified between 2014 and 2016 (4 to 17 SNPs, all ST269) (Table 1, Fig. 1). Almost 80,000 SNPs of difference were found between clusters. One isolate not belonging to either cluster was typed as ST92 (~ 50,000 and ~ 76,000 SNPs of difference with cluster I and II, respectively). Three environmental E. hormaechei from surface water, belonging to ST93, displayed 39 to 106 SNPs of difference with the clinical isolates in cluster I. The environmental sample from sewage water was ST269, showing 4 to 13 SNPs of difference with the clinical ST269 isolates in cluster II (Fig. 1). One C. freundii was identified as ST129, whereas the other exhibited a new, not yet assigned ST (2,024 SNPs of difference between them). The E. coli isolate was of ST131 and the two K. pneumoniae were of ST376 and ST17, respectively (22,961 SNPs of difference) (Table 1).

Epidemiological factors associated with VIM-acquisition without known risk factors

Among the 15 patients, three (including the patient with blaVIM-2 positive C. freundii) had a healthcare visit abroad (Croatia, Egypt, and Portugal, respectively) and one reported travel outside North America (to Austria, Germany, and France) without healthcare contact (Table 1). For all 14 patients with blaVIM-1, inpatient and outpatient visits to TIBDN hospitals, time of blaVIM-1 detection, healthcare visits abroad, and MLST clusters are shown in Fig. 2. Of note, patients #3 and #4 from cluster I were hospitalized on the same ward in hospital C, but not in the same room or at the same time. Patients in cluster II were all linked to acute care hospital F, with patient #6 being the first identified patient; this outbreak has been described elsewhere17. The only potential direct link between the two clusters was that patient #6 (cluster II) underwent gastroscopy about 1 month after patient #2 (cluster I) had a sigmoidoscopy in the endoscopy unit at hospital B. Three out of four patients from cluster I lived in relative proximity to each other and to hospital C (Supplementary Fig. 1), whereas the site where the related surface water sample was taken was more distant. The index patient from cluster II, the related sewage water isolate and hospital F were all centrally located (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Inpatient and outpatient healthcare contacts in the Toronto Invasive Bacterial Diseases Network surveillance area as well as hospital admissions abroad of patients with blaVIM-1-positive Enterobacteriaceae. Each black or grey bar represents a hospital visit or admission with the different hospitals represented by different letters, and out-patient visits only marked with an asterisk.

Chart reviews were performed on all 14 TIBDN patients with detection of blaVIM-1. Patients with (n = 7) and without (n = 7) known potential exposure were similar regarding risk factors, except for older age (87 vs. 71 years, P = 0.03) in those without explained acquisition. All three patients residing in long term care facilities (LTCFs) were in the group without explained acquisition (43% vs. 0%, P = 0.19), but all lived in different facilities (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 1). Six patients (43%) had an infection due to blaVIM-positive E. hormaechei (5 urinary tract infections; 1 blood stream infection).

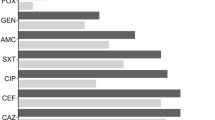

Susceptibility profiles and antimicrobial resistance genes

Susceptibility profiles and resistance mechanisms for clinical and environmental blaVIM-positive isolates are shown in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3. All isolates were resistant to at least one carbapenem. Ertapenem MICs ranged from 0.064 to ≥ 8 µg/ml (MIC50 and MIC90 of 2 and ≥ 8 µg/ml). For both meropenem and imipenem MICs ranged from 0.5 to ≥ 32 µg/ml (MIC50 of 4 and 8 µg/ml, respectively; MIC90 of 16 µg/ml for both). Only one isolate that was susceptible to meropenem (C. freundii Cfr-12) was also susceptible to cefepime: otherwise all isolates were resistant to all cephalosporins. All isolates but one were susceptible (or showed intermediate resistance, MIC = 8 µg/ml) to aztreonam (range 0.03 to 8 µg/ml; MIC50 and MIC90 of 2 and 4 µg/ml). Only one isolate, an extensively-drug resistant K. pneumoniae (Kpn-14), was highly resistant to aztreonam (MIC ≥ 256 µg/ml) and only susceptible to tigecycline and colistin.

In addition to blaVIM genes, all E. hormaechei in cluster I (except Eho-2) as well as the environmental Eho-E3 and Eho-E4 also had a plasmid-mediated AmpC (blaACC-1); similarly, blaCTX-M-15 was found in all E. hormaechei in cluster II. All these isolates harbouring blaACC-1 and blaCTX-M-15 displayed reduced susceptibility to aztreonam (MIC 1.5 to 4 µg/ml). Isolate Eho-1 had only an additional blaOXA-1, encoding for a narrow spectrum ß-lactamase, but also displayed an aztreonam MIC of 8 µg/ml. Two or more aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme genes were described in all the isolates, but only five isolates were resistant to gentamicin, and only three (from the three patients with a history of hospitalization in other countries) were resistant to amikacin. All isolates carried at least one plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance mechanism, but only nine isolates, which were also gyrA/parC double mutants, were highly resistant to nalidixic acid (MIC ≥ 256 µg/ml) and ciprofloxacin (≥ 32 µg/ml). All isolates were susceptible to tigecycline and colistin, and only one isolate (Kpn-14) was resistant to fosfomycin despite the fact that all cluster I isolates were fosA positive (see Supplementary Table 3).

Characterisation of plasmids carrying bla VIM genes

Features of VIM plasmids are detailed in Table 2 and Supplementary Figs. 2–7. Of fifteen VIM plasmids among E. hormaechei isolates, thirteen belonged to the IncR replicon type. Cluster I included one IncHI2 and four IncR plasmids, three of which had similar size (~ 38 kb) and shared high nucleotide identity (99.5%) (Supplementary Fig. 2). The remaining IncR plasmid in cluster I (environmental isolate Eho-E1 recovered from surface water in 2015) was larger (~ 65 kb) (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6). The plasmids in cluster II (including one environmental isolate Eho-E2) were homogeneous in size (~ 33 kb) and shared high nucleotide pairwise identity (99.2%) (Supplementary Fig. 3). Comparison of IncR plasmids from cluster I and cluster II identified a ~ 6.4 kb DNA fragment (encoding for the tetracycline efflux protein TetA and its repressor TetR) in cluster I but not in the cluster II plasmid (Supplementary Fig. 4). The two remaining environmental E. hormaechei isolates, recovered from the same surface water site on the same day, were also ST93 and carried IncR VIM plasmids of different sizes (Eho-E3, ~ 96 kb; Eho-E4, ~ 83 kb; 88.1% pairwise identity) (Supplementary Fig. 6), for which no significant alignments against the GenBank database were obtained.

One of the VIM-plasmids found in one clinical E. hormaechei isolate from cluster I (Eho-3, ST93) belonged to the IncHI2 (~ 325 kb) (Supplementary Fig. 7). Clinical isolate Eho-1 did not belong to any of the two previous clusters (it was typed as ST92) and harbored an IncFII/IncFIIB, blaVIM-1–plasmid of ~ 178 kb. Interestingly, this patient (patient 1) was found to be colonized upon transfer from Croatia, suggesting acquisition abroad. Indeed, the detection of the same sequence type in the same time period and institution has been documented18,19.

One C. freundii (Cfr-12, ST129) carried the blaVIM-2 gene in a 30 kb plasmid. It had almost 100% identity with pJB12 (KX889311), detected in four P. aeruginosa from inpatients of two different hospitals in Portugal20,21. pJB12 has the blaVIM-2-carrying In58 integron immersed in Tn6352, a transposon composed of the In58 and ISPa17 elements. Partial sequences of this In58 were found in GenBank, one from C. freundii (JX486753, uploaded in 2012) and the other from P. aeruginosa (KJ679406, uploaded in 2014), both from Aveiro, Portugal. Interestingly, the Ontario patient had a previous history of hospitalization in Aveiro in 2011, further supporting the hypothesis of acquisition abroad. However, since the Aveiro isolates and plasmids were not characterized, this possibility cannot be confirmed. It is also notable that even if the machinery for self-conjugation is incomplete, pJB12 might be mobilizable in the presence of a helper plasmid, a hypothesis that would be supported by the fact that this same plasmid was found in P. aeruginosa in Portugal and in C. freundii in Ontario, Canada (and potentially also in Portugal). The remaining C. freundii (Cfr-13) and K. pneumoniae (Kpn-13a) were colonizing the same patient (patient 13). The blaVIM-1 gene was identified in both cases on ~ 81 kb, IncN-IncR plasmids sharing 97.8% nucleotide identity, supporting the notion of intra-patient dissemination of this plasmid. The last two VIM-plasmids, with low nucleotide identity between them, were found in K. pneumoniae Kpn-14 and E. coli Eco-15 (Table 2).

All isolates carried the blaVIM genes in In110 integrons (blaVIM-1-aacA4′-aadA1b), except one C. freundii (In58: aacA7-blaVIM-2-aacC1-aacA4) (Supplementary Table 2). A new integron (In1772) was identified in the environmental E. hormaechei Eho-E3 and Eho-E4. In1772 has a truncated intI1 integrase gene, displaying a novel array of gene cassettes, similar to In110 (blaVIM-1-aacA4-10-aadA1b).

Discussion

In Southern Ontario, Canada, autochthonous cases of VIM-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae have repeatedly been detected over a period of almost seven years. In this study, two clusters (thereof one hospital outbreak) with two different E. hormaechei sequence types but closely related plasmids suggest clonal spread and potential horizontal gene transfer as responsible for blaVIM dissemination. The additional detection of identical E. hormaechei isolates in sewage and surface water suggests that the reservoirs may not solely be the gastrointestinal tract of patients. We could not identify common exposures among patients with unexplained VIM-acquisition. With the exception of a probable intra-patient horizontal dissemination of blaVIM (patient 13), VIM-plasmids in clinical isolates from other bacterial species were not similar suggesting independent acquisition.

Our results suggest a common ancestral IncR plasmid for patient clusters I and II. Although it has been postulated that IncR plasmids are mobilizable because of their broad host range22, they may in fact be non-transferable and non-mobilizable due to the lack of a transfer system and a relaxase23,24,25. These features suggest that the evolution of these IncR plasmids occurred independently in clinical and environmental isolates belonging to the same clonal groups, with more structural stability among clinical isolates.

E. hormaechei, a member of the E. cloacae complex, was the most frequently isolated pathogen among blaVIM-positive Enterobacteriaceae and the only Enterobacter spp. carrying blaVIM in our analysis. This association has also been found in an analysis of a collection of 170 Enterobacter isolates from around the globe, where blaVIM was the most commonly detected carbapenemase14. Enterobacter spp. are colonizers of the human gastrointestinal tract, which is considered to be the primary reservoir for nosocomial infections. Such infections occur primarily in highly debilitated patients after prolonged hospitalization and exposure to antibiotics26. Numerous hospital outbreaks such as the one described in cluster II have been described12,17,18,27. Many reports from the USA and Europe have also identified LTCFs as reservoirs for CPE, including VIM28,29,30. Although three of four patients from cluster I were residents of LTCFs, they lived in three different facilities with different ownership separated by 5–50 km. In our setting, direct transfers between LTCFs are rare and are unlikely to provide a connection between these cases. However, indirect transmission via stays in acute care hospitals serving these institutions (such as hospitals B or C), or shared staff and equipment might explain acquisition of these strains. The similarity in characteristics of cases with explained and unexplained sources suggests that undetected colonized patients are the most likely sources of new acquisitions in our setting.

Common exposure to non-healthcare sources (to a food or environmental source) is another possible explanation for our findings. Interestingly, VIM is among the most frequently reported carbapenemases responsible for contamination of the hospital water environment, which may also be a source for new acquisitions31. Several studies have identified blaVIM from non-healthcare sources such as sewage and surface waters6,7,8,9,10, drinking water32, sea gulls33, and from seafood34,35. Of note, reports from Europe have demonstrated the isolation of identical CPE from environmental water and patient samples36, 37, most likely acquired during recreational swimming37. We cannot determine from our study whether our water isolates are a result of contamination from colonized patients, or whether these water sources represent an environmental reservoir from which patients may acquire VIM. Geographical mapping of patient residences and environmental sampling did not reveal any clear association.

In addition to autochthonous cases, importation from hospitals with endemic or epidemic VIM-producing Enterobacteriaceae is also occurring. One third of patients with VIM-producing organisms had a hospital admission abroad in the year prior to detection; most of whom were repatriated from high-risk countries. The two cases with presumable VIM-acquisition in Croatia and Portugal, supported by high-resolving molecular data, highlight the importance of CPE screening and pre-emptive isolation in patients with a history of hospitalization in institutions with endemic or epidemic CPE.

A strength of our study is the availability of population-based CPE surveillance data. Together with the thorough patient workup this enabled us to get a complete picture of the local epidemiology and to reliably identify common exposures between patients. Furthermore, detailed microbiologic investigations including WGS allowed us to complement the epidemiological data.

Our study has limitations. The definition of explained and unexplained VIM-acquisition is arbitrary. We nevertheless think that considering both epidemiologic and microbiologic criteria for this definition assists in understanding the source and transmission of carbapenemases. Another limitation is the lack of patient information regarding non-healthcare exposures such as food or environment (e.g. exposure to environmental water), although the patients’ age and comorbidities make this scenario rather unlikely. Also, the number of environmental samples in our study was rather small.

In conclusion, VIM-1 producing Enterobacteriaceae are sporadically being reported in Ontario and mainly involve E. hormaechei. Dissemination of these pathogens is most likely due to undetected colonization and transmission in acute care and, potentially, LTCF. Further studies are needed to examine the role of LTCF and of environmental contamination in the local epidemiology of VIM-1.

Methods

Setting and sample sources

TIBDN has performed population-based surveillance of CPE in metropolitan Toronto and Peel Region from the time of their first identification in 200716. Population-based surveillance was actively started in July 2014. To identify cases before July 2014, various data sources were consulted, including data from a voluntary surveillance program, microbiology laboratories, infection control departments, and Public Health Ontario Laboratories. For this analysis, we included all blaVIM-positive Enterobacteriaceae identified by TIBDN laboratories between October 2007 and January 2016. Four environmental VIM-positive Enterobacter cloacae complex isolates which were recovered in July–August 2015 from sewage and surface water in Toronto were also included38.

Patient data

For patients colonized or infected with blaVIM-positive Enterobacteriaceae, travel history including healthcare abroad was collected by chart review and patient interview. Chart review was performed for all hospital admissions and outpatient visits in TIBDN hospitals from one year before first CPE detection until April 2016.

Data on epidemiological (e.g. LTCFs, previous hospital admissions and healthcare visits) and clinical risk factors (e.g. comorbidities, antibiotic exposure, medical interventions)—mainly based on reports from the literature—within 365 days before first VIM detection were collected28,31,39.

Microbiology investigations

For identification of CPE, TIBDN laboratories adhere to a standardized diagnostic process40. Carbapenem-resistant enterobacterial isolates with phenotypic production of a carbapenemase underwent PCR screening for the most common carbapenemase genes (blaVIM, blaNDM, blaKPC, blaOXA-48, blaIMP, blaGES, blaSME, and blaNMC). Environmental sampling was performed as previously described38.

MALDI-TOF MS (bioMérieux VITEK-MS) was performed on all pure cultures to identify organisms to the species level. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing by Etest (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) or broth microdilution was performed and interpreted using the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines41, except in the case of colistin42. Because there are no breakpoints for tigecycline in the 2019 CLSI and EUCAST (only for Escherichia coli and Citrobacter koseri) guidelines, we used the 2018 EUCAST breakpoints (S ≤ 1 µg/ml; R > 2 µg/ml) for interpretation of species other than E. coli.

Whole-genome sequencing and bioinformatics

Genomic DNA extraction, Illumina sequencing libraries and sequencing runs were performed as described43. Nanopore sequencing was performed on Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) MinION device with chemistry 8 and flow cells FLO-MIN106 version R9.4. DNA was extracted using the MasterPure Complete DNA & RNA Purification kit (Epicenter Illumina, Wisconsin USA) with elution carried out to a final volume of 40 µL in TE buffer. Libraries for 12 isolates were prepared with the Rapid Barcoding Kit SQK-RBK004 starting with 400 ng of high molecular weight DNA from each isolate and according to Oxford Nanopore protocol (RBK_9054_V2_revE_23jan2018). Libraries were loaded and run for 48 h. Base calling was performed while sequencing or using Guppy. Nanoplot was used for quality control. Porechop (https://github.com/rrwick/Porechop) was used to split files by and to trim barcodes. Illumina-ONT hybrid assemblies were performed using Unicycler. Circular plasmid sequences were obtained from the hybrid assemblies. The assembled sequences were annotated using the RAST server (https://rast.nmpdr.org/rast.cgi) and the sequences compared in a pairwise fashion using BRIG44.

Resistance genes were detected using the StarAMR pipeline (https://github.com/phac-nml/staramr), which scans genome contigs against the ResFinder, PlasmidFinder, and PointFinder databases (Center for Genomic Epidemiology). Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) for E. cloacae, E. coli and K. pneumoniae were carried out in silico using assembled contigs (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/MLST/)45. Single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis was conducted using a custom pipeline. Briefly, reads for all isolates were mapped against reference strain using SMALT software (v 0.7.6). The reference strains used are the follow: Enterobacter cloacae AR_0053 (GenBank BioSample: SAMN04014894; BioProject PRJNA292904); Klebsiella pneumoniae HS11286 (ASM24018v2, GenBank BioSample: SAMN02602959, BioProject: PRJNA78789); Citrobacter freundii CFNIH1 (ASM64851v1, GenBank BioSample: SAMN02713684, BioProject: PRJNA202883). SNP calling was performed using Freebayes with: min-base-quality 30, minmapping-quality 30, min-alternate-fraction 0.75, read-snp-limit 10, min-coverage 15. Additional variant confirmation was done using the SAMtools mpileup tool. Repetitive regions were removed by using MUMmer. The meta-alignment of core informative positions was used to create a maximum likelihood tree using MEGA 7. Integron numbers were assigned by INTEGRALL, available at https://integrall.bio.ua.pt/46. The genome sequences for the isolates included in this study are deposited with NCBI, BioProject ID: PRJNA599404.

Case–control study

A case–control study was performed among patients with blaVIM-1-positive Enterobacteriaceae to identify possible epidemiological risk factors for acquisition of blaVIM-1. Patients without a plausible source of acquisition were defined as cases, those with known risk as controls. Plausible sources of acquisition were defined as exposure as a patient in any hospital abroad OR spatiotemporal linkage (i.e. same hospital room within 3 months) to another patient in a TIBDN hospital with a VIM-containing isolate of the same species and MLST-type.

Statistical analyses

We used SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for all statistical analyses. A two-tailed P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and proportions, continuous variables as median with range. For the case–control study, univariate analysis was performed using chi-square test or Fisher-exact, as appropriate, for dichotomous variables, and the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables.

Ethics

Informed consent was obtained for patients with any specimen yielding CPE after January 2013, but consent was waived for those with positive specimens prior to 2013 only. This approach was approved by institutional review boards of all participating TIBDN hospitals and Public Health Ontario. The study was performed according to the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

References

Walsh, T. R., Toleman, M. A., Poirel, L. & Nordmann, P. Metallo-lactamases: the Quiet before the Storm?. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18, 306–325 (2005).

Giani, T. et al. Epidemic diffusion of KPC carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Italy: results of the first countrywide survey, 15 May to 30 June 2011. Euro Surveill. 18, 1 (2013).

Spyropoulou, A. et al. A ten-year surveillance study of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a tertiary care Greek university hospital: predominance of KPC- over VIM- or NDM-producing isolates. J. Med. Microbiol. 65, 240–246 (2016).

Pérez-Vazquez, M. et al. Characterization of Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella oxytoca in Spain, 2016–2017. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 63, 1–12 (2019).

Zurfluh, K. et al. Wastewater is a reservoir for clinically relevant carbapenemase- and 16s rRNA methylase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 50, 436–440 (2017).

Müller, H. et al. Dissemination of multi-resistant Gram-negative bacteria into German wastewater and surface waters. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 94, 5 (2018).

Kieffer, N. et al. VIM-1, VIM-34, and IMP-8 carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli strains recovered from a Portuguese river. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60, 2585–2586 (2016).

Zurfluh, K., Hächler, H., Nüesch-Inderbinen, M. & Stephan, R. Characteristics of extended-spectrum β-lactamase- and carbapenemase-producing enterobacteriaceae isolates from rivers and lakes in Switzerland. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 3021–3026 (2013).

Zarfel, G. et al. Troubled water under the bridge: Screening of River Mur water reveals dominance of CTX-M harboring Escherichia coli and for the first time an environmental VIM-1 producer in Austria. Sci. Total Environ. 593–594, 399–405 (2017).

Piedra-Carrasco, N. et al. Carbapenemase-producing enterobacteriaceae recovered from a Spanish river ecosystem. PLoS ONE 12, e0175246 (2017).

Cornaglia, G., Giamarellou, H. & Rossolini, G. M. Metallo-β-lactamases: a last frontier for β-lactams?. Lancet. Infect. Dis 11, 381–393 (2011).

Yaffee, A. Q. Notes from the field: verona integron-encoded metallo-beta-lactamase–producing carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae in a neonatal and adult intensive care unit—Kentucky, 2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 65, 1–12 (2016).

Tamma, P. D. et al. First report of a verona integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae infection in a child in the United States. J. Pediatric Infect. Dis. Soc. 5, e24–e27 (2016).

Peirano, G. et al. Genomic epidemiology of global carbapenemase-producing Enterobacter spp., 2008–2014. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 24, 1010–1019 (2018).

Tijet, N. et al. Verona integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamase 1 in enterobacteria, Ontario, Canada. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 19, 1156–1158 (2013).

Kohler, P. P. et al. Emergence of carbapenemase-producing enterobacteriaceae, South-Central Ontario, Canada. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 24, 1674–1682 (2018).

Candon, H. Transmission of VIM-producing Enterobacteriaceae over a two-year period linked to contaminated drains. Abstract 245. IDWeek New Orleans, 2016.

Novak, A. et al. Monoclonal outbreak of VIM-1-carbapenemase-producing Enterobacter cloacae in intensive care unit, University Hospital Centre Split, Croatia. Microbial. Drug Resist. 20, 399–403 (2014).

Bedenić, B. et al. Molecular characterization of class b carbapenemases in advanced stage of dissemination and emergence of class d carbapenemases in Enterobacteriaceae from Croatia. Infect. Genet. Evol. 43, 74–82 (2016).

Botelho, J., Grosso, F. & Peixe, L. Characterization of the pJB12 plasmid from Pseudomonas aeruginosa reveals Tn 6352, a Novel putative transposon associated with mobilization of the bla VIM-2 -harboring In58 integron. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61, e02532-e2616 (2017).

Botelho, J. et al. Two decades of blaVIM-2-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa dissemination: an interplay between mobile genetic elements and successful clones. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 73, 873–882 (2018).

Bielak, E. et al. Investigation of diversity of plasmids carrying the blaTEM-52 gene. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66, 2465–2474 (2011).

Smillie, C., Garcillán-Barcia, M. P., Francia, M. V., Rocha, E. P. C. & de la Cruz, F. Mobility of plasmids. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 74, 434–452 (2010).

Papagiannitsis, C. C., Miriagou, V., Giakkoupi, P., Tzouvelekis, L. S. & Vatopoulos, A. C. Characterization of pKP1780, a novel IncR plasmid from the emerging Klebsiella pneumoniae ST147, encoding the VIM-1 metallo-β-lactamase. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68, 2259–2262 (2013).

Compain, F. et al. Complete nucleotide sequence of two multidrug-resistant IncR plasmids from Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 4207–4210 (2014).

Sanders, W. E. & Sanders, C. C. Enterobacter spp.: pathogens poised to flourish at the turn of the century. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10, 22 (1997).

Tato, M. et al. Complex clonal and plasmid epidemiology in the first outbreak of Enterobacteriaceae infection involving VIM-1 metallo- -lactamase in Spain: toward endemicity?. Clin. Infect. Dis. 45, 1171–1178 (2007).

Lin, M. Y. et al. The importance of long-term acute care hospitals in the regional epidemiology of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin. Infect. Dis. 57, 1246–1252 (2013).

Aschbacher, R. et al. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae during 2011–12 in the Bolzano area (Northern Italy): increasing diversity in a low-endemicity setting. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 77, 354–356 (2013).

Ruiz-Garbajosa, P. et al. A single-day point-prevalence study of faecal carriers in long-term care hospitals in Madrid (Spain) depicts a complex clonal and polyclonal dissemination of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71, 348–352 (2016).

KiznyGordon, A. E. et al. The hospital water environment as a reservoir for carbapenem-resistant organisms causing hospital-acquired infections: a systematic review of the literature. Clin. Infect. Dis. 64, 1435–1444 (2017).

Fernando, D. M. et al. Detection of antibiotic resistance genes in source and drinking water samples from a first nations community in Canada. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82, 4767–4775 (2016).

Vittecoq, M. et al. VIM-1 carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli in gulls from southern France. Ecol. Evol. 7, 1224–1232 (2017).

Roschanski, N. et al. VIM-1 carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli isolated from retail seafood, Germany 2016. Euro Surveill. 22, 43 (2017).

Rubin, J. E., Ekanayake, S. & Fernando, C. Carbapenemase-producing organism in food, 2014. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 20, 1264–1265 (2014).

Khan, F. A., Hellmark, B., Ehricht, R., Söderquist, B. & Jass, J. Related carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella isolates detected in both a hospital and associated aquatic environment in Sweden. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 37, 2241–2251 (2018).

Laurens, C. et al. Transmission of IMI-2 carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae from river water to human. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 15, 88–92 (2018).

Kim, H. C. Isolation of Carbapenemase Producing Enterobacteriaceae in the Greater Toronto Area’s Sewage Treatment Plants and Surface Waters, and their Comparison to Clinical CPE from Toronto. Master thesis. https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/74976/1/Kim_Hyunjin_C_201611_MSc_thesis.pdf.

Voor In’ t Holt, A. F. et al. VIM-positive Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a large tertiary care hospital: matched case-control studies and a network analysis. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 7, 32 (2018).

Cabrera, A. Detection of Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in TIBDN Laboratories, 2014. Abstract F02 AMMI Canada, 2016. https://www.ammi.ca/Annual-Conference/2016/Abstracts/2016JAMMIAbstracts.pdf.

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing—Twenty-Eighth Edition: M100 (CLSI, Wayne, 2018).

European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing guidelines, EUCAST, version 9.0. https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Breakpoint_tables/v_9.0_Breakpoint_Tables.pdf.

Gianecini, R. A. et al. Use of whole genome sequencing for the molecular comparison of neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates with decreased susceptibility to extended spectrum cephalosporins from 2 geographically different regions in America. Sex. Transm. Dis. 46, 548–555 (2019).

Alikhan, N.-F., Petty, N. K., Ben Zakour, N. L. & Beatson, S. A. BLAST Ring Image Generator (BRIG): simple prokaryote genome comparisons. BMC Genom. 12, 402 (2011).

Larsen, M. V. et al. Multilocus sequence typing of total-genome-sequenced bacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50, 1355–1361 (2012).

Moura, A. et al. INTEGRALL: a database and search engine for integrons, integrases and gene cassettes. Bioinformatics 25, 1096–1098 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Information (313039 to A. McGeer) and the Swiss National Science Foundation (158728 to P. Kohler).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

P.K., B.C., K.G., A.M., and R.M. were responsible for study design and conceptualization. J.J., K.G., I.A., K.K., M.M., J.P., D.R., A.Sa., A.Si., and A.M. provided clinical isolates and patient data. H.K., T.E., B.W., and A.M. collected environmental isolates or were responsible for environmental sampling. N.T., H.K., T.E., S.P., C.S., B.W., S.P., and R.M. performed the microbiological analyses. P.K. and A.M. analyzed the epidemiological data. A.M. and R.M. were responsible for study funding. P.K., A.M., and R.M. drafted the first version of the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr. Poutanen reports having received honoraria from Merck related to advisory boards and talks, honoraria from Verity, Cipher, and Paladin Labs related to advisory boards, partial conference travel reimbursement from Copan, and research support from Accelerate Diagnostics and bioMérieux, all outside the submitted work. The other authors do not report any conflict of interest. The authors do not report any further competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kohler, P., Tijet, N., Kim, H.C. et al. Dissemination of Verona Integron-encoded Metallo-β-lactamase among clinical and environmental Enterobacteriaceae isolates in Ontario, Canada. Sci Rep 10, 18580 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75247-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75247-7

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.