Abstract

The eradication rate of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) has been decreasing every year, mainly due to the increase in antibiotic resistance. In fact, many other factors may affect H. pylori eradication. To analyze the clinical factors affecting the initial eradication therapy in Chinese patients with H. pylori infection. We conducted a retrospective study on 264 outpatients who were diagnosed with H. pylori-associated chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer disease between January and December 2015 at a large tertiary hospital in China. The patients were divided into three groups: ECA, RCA, and RCM (R: 20 mg rabeprazole, E: 40 mg esomeprazole, C: 0.5 g clarithromycin, A: 1.0 g amoxicillin and M: 0.4 g metronidazole). The patients were treated for 14 days and followed up for 1 year. The 14C-urea breath test (14C-UBT) was performed 4 weeks after the completion of the eradication therapy. The eradication rate was higher in ≥ 40-year-old patients than in < 40-year-old-patients (85.7% vs. 54.7%, p = 0.002). Multivariate analyses revealed only age ≥ 40 years to be significantly associated with a high H. pylori eradication rate [odds ratio (OR) 4.58, p = 0.003]. The H. pylori eradication rate in patients with duodenal ulcers was significantly higher than that in patients with gastric ulcers (79% vs. 60%, p = 0.012). Age could be a predictor of successful H. pylori eradication. Patients with duodenal ulcers had a higher H. pylori eradication rate than those with other lesions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

More than 50% of the global population has been estimated to be infected with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori). Socioeconomic conditions and ethnicity influence H. pylori infection1,2,3.

The H. pylori infection rate is relatively higher in China, and the infection is more frequently observed in the countryside than in urban areas.

H. pylori is the primary cause in most cases of peptic ulcer disease (PUD), gastric cancer, and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (MALT). It has also been reported to cause functional dyspepsia, iron deficiency anemia, and neurodegenerative disease4.

Successful H. pylori eradication therapy can usually prevent the relapse of PUD and reduce corresponding complications even after stopping all treatments. In a previous study in which early gastric cancer was treated endoscopically, the risk of metachronous gastric neoplasms was found to decrease after H. pylori eradication5. H. pylori eradication could significantly decrease the risk of gastric cancer and prevent its occurrence, especially in patients with early-stage H. pylori infection6,7.

The eradication rates of H. pylori have been decreasing every year. Several studies have shown the eradication rates to be 75%5,8. Resistances to antibiotics, particularly clarithromycin, is the crucial factor affecting H. pylori eradication therapy9,10. The clarithromycin resistance rate has been found to be up to 50% in China11. There are regional differences for resistance rate to clarithromycin. Another literature reported that the resistance rate to clarithromycin was 17.76% in Jiaxing City of China12. However, H. pylori culture is time-consuming, difficult, and expensive and has a low positive rate. To our knowledge, few studies have been conducted on the clinical factors affecting the eradication therapy in China. We aimed to analyze the clinical factors associated with the initial eradication therapy and to explore possible solutions.

Materials and methods

Patients

In total, 264 outpatients aged 18–70 years with current H. pylori-associated chronic gastritis and PUD diagnosed between January and December 2015 were chosen for the present study. The majority of the patients were from rural areas.

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

(1)

A history of gastrectomy.

-

(2)

The presence of gastric cancer.

-

(3)

Receipt of any antibiotics, bismuth compounds, or proton pump inhibitors (PPI) within 1 year before the study and prior H. pylori eradication.

-

(4)

The presence of chronic renal failure, hepatic disease, congestive heart failure, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

-

(5)

Pregnancy or lactation.

-

(6)

Inability to follow up.

Methods

All the patients were divided into three groups: ECA, RCA, and RCM (R: 20 mg rabeprazole, E: 40 mg esomeprazole, C: 0.5 g clarithromycin, A: 1.0 g amoxicillin, and M: 0.4 g metronidazole). PPI were administered before breakfast and dinner, and antibiotics were administered after breakfast and dinner. The patients were treated for 14 days and followed up for 1 year.

H. pylori was detected by the 14C-urea breath test (14C-UBT)13 using the 14C-urea breath machine (Shenzhen Haidewei Technology Co. Ltd., Shenzhen, China) before and 4 weeks after treatment. The cut-off value of the 14C-UBT was 100 dpm/mmol CO2. Clinical data were then collected.

The study was conducted at the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi University of Science and Technology, Liuzhou, China. The hospital is a tertiary care center. All experimental protocols were approved by the ethics and research committees of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi University of Science and Technology. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations from the Maastricht IV/Florence Consensus Report14. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were mean ± standard deviation (SD) for age and chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test for rates. Independent factors that may have been associated with successful eradication were assessed using multiple logistic regression analysis. The following variables were analyzed as independent factors: sex, age, lesion characteristics, and treatment groups. p values < 0.05 were thought to be statistically significant. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 19.0.

Results

The clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 44 ± 12 years (male: female, 3.2:1).

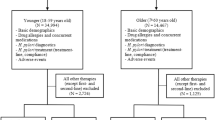

All eradication rates were analyzed per protocol because the patients who had completed the therapy were investigated. The eradication rates by age group were 75%, 47%, 83%, 85%, and 100% for < 30, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, and ≥ 60-year-old patients, respectively. The eradication rate was the lowest in 30–39-year-old patients and the highest ≥ 60-year-old patients (47% vs. 100%, Fig. 1). The eradication rate in ≥ 40-year-old patients was higher than that in < 40-year-old patients, even after adjusting for other factors [odds ratio (OR) 4.58, p = 0.003, Table 2].

The eradication rates by lesion characteristics were 77%, 60%, 79%, and 71% for patients with chronic gastritis, gastric ulcers, duodenal ulcers, and both gastric and duodenal ulcers, respectively. The eradication rate in patients with duodenal ulcers was higher than that in patients with gastric ulcers (79% vs. 60%, p < 0.05). Moreover, the eradication rate was similar between males and females (76% vs. 74%, p = 0.68). The eradication rate did not differ significantly between the ECA and RCA groups (85% vs. 82%, p = 0.542). The eradication rates in the ECA (85%) and RCA (82%) groups were significantly higher than that in the RCM group (60%) (p = 0.007 and 0.036, respectively) (Table 1).

The incidence of adverse events was 9.5% (95% CI 0.7–18.3). Diarrhea and taste perversion were commonly observed. None of the patients discontinued the therapy because of adverse effects.

In the final logistic regression model, the effects of age on H. pylori eradication were estimated after adjusting for all other factors. The effects of lesion characteristics and treatment groups were not significant, and these factors were therefore not included in the final model.

Discussion

Maastricht IV/Florence Consensus Report14 pointed out that different ways of improving the PPI-clarithromycin-amoxicillin/metronidazole regimens have been proposed such as increase of the dose of PPI and the length of treatment. Both the increase of the dose of PPI and extended duration of treatment have been considered in our study.

Our study revealed a link between age and H. pylori eradication therapy. Compared with < 40-year-old patients, we found a higher eradication rate in ≥ 40-year-old patients, even after adjusting for other factors. The eradication rate was 100% in patients aged over 60 years. As reported by Japanese scholars, patients aged under 50 years are prone to H. pylori eradication failure. The eradication rate in patients aged over 70 years has been found to be over 90%. Independent predictors of treatment success include older age15,16. The gastric mucosa is more atrophic in elderly patients than in younger patients and has hyposecretion of gastric acid. The ability of gastric acid to inactivate antibiotics decreases in elderly patients.

The incidence of PUD and bleeding complications is increasing in elderly patients worldwide. Approximately 53–73% of elderly patients with peptic ulcers are positive for H. pylori. The benefit of curing H. pylori infection in elderly patients with H. pylori-associated PUD and severe chronic gastritis has been demonstrated in a previous study17. The eradication rate in elderly patients was found to be higher in our study. Eradication should be performed in elderly patients.

There are several possible reasons for the lower eradication rate observed in young patients. One explanation is that young people tend to forget to take medicines because of busy work schedules18. Moreover, some younger patients stopped the therapy by themselves because their symptoms ameliorated shortly after taking PPI. Medication adherence and factors affecting adherence play a very important role in H. pylori eradication therapy. Another explanation is that young patients may have many bad habits, including irregular meal timings, smoking, alcohol abuse, and staying up too late. Finally, young patients may not have regular checkups.

It is particularly important to assess how the eradication outcomes can be improved in young patients. There is no simple solution to this problem. Several methods are recommended to resolve this issue. First, doctors should explain the necessity of eradication and the harmful consequences of irregular medication to patients. At the same time, bad habits, such as smoking, irregular meal timings, and alcohol abuse, should be stopped. Second, better therapeutic strategies and the reasons for eradication failure should be explored. Individualized treatment should be considered. Third, the follow-up program should be improved. Regular checkups should be recommended.

Previous studies have suggested that probiotic supplementation can increase the eradication rate in young patients17,19. A Japanese research team found that the use of a new antisecretory agent, potassium-competitive acid blocker (PCAB), instead of PPI and clarithromycin-based triple therapy increased the eradication rate in young to middle-aged patients20. Intragastric violet light phototherapy21 and bovine anti-H. pylori antibody-containing milk22 could eradicate H. pylori. Moreover, smoking cessation may increase the H. pylori eradication rate23. Correct evaluation of the quality improvement protocol can confirm the strategies that are most successful in every patient and dispel inaccurate perceptions, which can then be considered in the case of other patients as well.

We found that the eradication rate in patients with duodenal ulcers was significantly higher than that in patients with gastric ulcer (79% vs. 60%). A previous study revealed significantly different failure rates between patients with duodenal ulcers and non-ulcer dyspepsia (21.9% vs. 33.7%, p < 10−6)24. H. pylori therapy is always thought to be related to gastric acid secretion. Gastric acid secretion is low in patients with gastric ulcers and high in those with duodenal ulcers. The lower gastric acid concentration in patients with gastric ulcers to inactivate antibiotics decreases. So it’s difficult to explain the reason by the secretion of gastric acid. The reasons are not yet clearly understood. It could be related to patient differences, or the status of the gastric mucosa, or to differences in the infecting H. pylori strain. Multicenter clinical trials have indicated that patients with duodenal ulcers and non-ulcer dyspepsia should be managed differently in medical practice and considered independently in eradication trials24.

There are some limitations to our study. First, our study has a retrospective design. Many risk factors, such as habits (smoking and alcohol use), were not considered in our study. Second, our study was conducted at a single academic medical center and had sample bias. There are two advantages of conducting the study at our hospital. It is a large medical center that serves almost 5 million people. Moreover, patients with different occupations and from different places visit the hospital. Thus, patient diversity can be ensured. Third, the number of elderly patients was small. A larger sample size consisting of more elderly patients is needed for more careful investigation.

In conclusion, in our study, age was found to be associated with H. pylori eradication. Patients with duodenal ulcers had a higher H. pylori eradication rate than those with other lesions. Younger patients, especially those with gastric ulcers, had a lower eradication rate. Further studies are needed to explore why the eradication rate is lower and how it can be increased in these patients. Predicting the success of H. pylori eradication therapy and choosing the appropriate therapeutic schedule based on clinical parameters will benefit the patients and decrease healthcare costs.

References

Eusebi, L. H., Zagari, R. M. & Bazzoli, F. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter 19(Suppl 1), 1–5 (2014).

Santos, I. S. et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and associated factors among adults in Southern Brazil: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 5, 118 (2005).

Syam, A. F. et al. Risk factors and prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in five largest islands of Indonesia: a preliminary study. PLoS ONE 10, e0140186 (2015).

Diaconu, S., Predescu, A., Moldoveanu, A., Pop, C. & Fierbințeanu-Braticevici, C. Helicobacter pylori infection: old and new. J. Med. Life 10, 112–117 (2017).

Paoluzi, P. et al. 2-week triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection is better than 1-week in clinical practice: a large prospective single-center randomized study. Helicobacter 11, 562–568 (2006).

Rokkas, T., Rokka, A. & Portincasa, P. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the role of Helicobacter pylori eradication in preventing gastric cancer. Ann. Gastroenterol. 30, 414–423 (2017).

Argent, R. H. et al. Toxigenic Helicobacter pylori infection precedes gastric hypochlorhydria in cancer relatives, and H. pylori virulence evolves in these families. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 2227–2235 (2008).

Gisbert, J. P., Domínguez-Muñoz, A., Domínguez-Martín, A., Gisbert, J. L. & Marcos, S. Esomeprazole-based therapy in Helicobacter pylori eradication: any effect by increasing the dose of esomeprazole or prolonging the treatment?. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 100, 1935–1940 (2005).

Seo, S. I. et al. Is there any difference in the eradication rate of Helicobacter pylori infection according to the endoscopic stage of peptic ulcer disease?. Helicobacter 20, 424–430 (2015).

Arenas, A. et al. High prevalence of clarithromycin resistance and effect on Helicobacter pylori eradication in a population from Santiago, Chile: cohort study and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–9 (2019).

Thung, I. et al. Review article: the global emergence of Helicobacter pylori antibiotic resistance. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 43, 514–533 (2016).

Ji, Z. et al. The association of age and antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter Pylori: a study in Jiaxing City, Zhejiang Province China. Medicine (Baltimore) 95, e2831 (2016).

Coelho, L. G. et al. 3rd Brazilian consensus on Helicobacter pylori. Arq. Gastroenterol. 50, 81–96 (2013).

Malfertheiner, P. et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht IV/Florence consensus report. Gut 61, 646–664 (2012).

Mamori, S. et al. Age-dependent eradication of Helicobacter pylori in Japanese patients. World J. Gastroenterol. 16, 4176–4179 (2010).

Boltin, D. et al. Comparative effect of proton-pump inhibitors on the success of triple and quadruple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection. Dig. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1159/000504909 (2020).

Pilotto, A. Aging and upper gastrointestinal disorders. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 18(Suppl), 73–81 (2004).

Shakya Shrestha, S. et al. Medication adherence pattern and factors affecting adherence in Helicobacter Pylori eradication therapy. Kathmandu Univ. Med. J. (KUMJ) 14, 58–64 (2016).

Shimbo, I. et al. Effect of Clostridium butyricum on fecal flora in Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. World J. Gastroenterol. 11, 7520–7524 (2005).

Nishizawa, T. et al. Effects of patient age and choice of antisecretory agent on success of eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 60, 208–210 (2017).

Lembo, A. J. et al. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection with intra-gastric violet light phototherapy: a pilot clinical trial. Lasers Surg. Med. 41, 337–344 (2009).

Hu, D. et al. The clearance effect of bovine anti-Helicobacter pylori antibody-containing milk in O blood group Helicobacter pylori-infected patients: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. J. Transl. Med. 13, 205 (2015).

Camargo, M. C. et al. Effect of smoking on failure of H. pylori therapy and gastric histology in a high gastric cancer risk area of Colombia. Acta Gastroenterol. Latinoam. 37, 238–245 (2007).

Broutet, N. et al. Risk factors for failure of Helicobacter pylori therapy: results of an individual data analysis of 2751 patients. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 17, 99–109 (2003).

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate Xiaotong Bo for his very constructive suggestions, which helped improve the manuscript. This research was supported by self-raised project of the Health Department in Guangxi Autonomous Region (No. Z2014446).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.T and G.T. in charge of substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, analysis and interpretation of data for the work; L.P., H.Z., S.Z., Z.W. were responsible for data collection, Y.T. drafted the manuscript, G.T revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, Y., Tang, G., Pan, L. et al. Clinical factors associated with initial Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy: a retrospective study in China. Sci Rep 10, 15403 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72400-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72400-0

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.