Abstract

Exceptional and extremely rare preservation of soft parts, eyes, or syn-vivo associations provide crucial palaeoecological information on fossil-rich deposits. Here we present exceptionally preserved specimens of the polychelidan lobster Voulteryon parvulus, from the Jurassic of La Voulte-sur-Rhône Fossil-Lagerstätte, France, bearing eyes with hexagonal and square facets, ovaries, and a unique association with epibiont thecideoid brachiopods, giving insights onto the palaeoenvironment of this Lagerstätte. The eyes, mostly covered in hexagonal facets are interpreted as either apposition eyes (poorly adapted to low-light environment) or, less likely, as refractive or parabolic superposition eyes (compatible with dysphotic palaeoenvironments). The interpretation that V. parvulus had apposition eyes suggests an allochthonous, shallow water origin. However, the presence of thecideoid brachiopod ectosymbionts on its carapace, usually associated to dim-light paleoenvironments and/or rock crevices, suggests that V. parvulus lived in a dim-light setting. This would support the less parsimonious interpretation that V. parvulus had superposition eyes. If we accept the hypothesis that V. parvulus had apposition eyes, since the La Voulte palaeoenvironment is considered deep water and had a soft substrate, V. parvulus could have moved into the La Voulte Lagerstätte setting. If this is the case, La Voulte biota would record a combination of multiple palaeoenvironments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The process of fossilisation offers only a partial insight into past environments: the morphological features of organisms are preserved, but their biotic interactions and their surrounding palaeoenvironments are rarely directly observable, except in a few specific cases. Consequently, comparison with extant species is the only tool that palaeontologists usually have to understand past environments. However, the ecology of extant species may differ from that of their fossil relatives. An example is the polychelidan lobsters; a group of decapod crustaceans characterized by having four to five pairs of claws. From their first occurrence in the Triassic to Jurassic, they had well-developed eyes and occurred in various environments and depths1, while the few extant species all have reduced eyes and live in deep waters worldwide2,3.

Beurlen4 and Ahyong3 proposed that polychelidans through their evolution have shifted bathymetric ranges from shallow to deep waters. Nevertheless, the evolutionary history of polychelidans, their palaeobathymetry, and their visual systems are complex. Indeed, two distinct visual systems, apposition and reflective superposition, occur within polychelidans5, and while many species are reported from shallow waters, some of the earliest species inhabited deep waters6,7. To understand the evolutionary history of the group through time it is of utmost importance to examine the environment of each species and their phylogenetic relationships.

The Middle Jurassic La Voulte-sur-Rhône Lagerstätte (Callovian: ca 165 Ma) is one of the most diverse and prolific localities for polychelidan lobsters in the world. Its palaeoenvironment has been interpreted as deep-water to bathyal (more than 200 meters), possibly at the transition between the continental slope and the basin8,9 (see also geological context in the Supplementary Information). However, recent observation of the eyes of a thylacocephalan from La Voulte suggested that the palaeoenvironment was possibly well-illuminated and therefore shallower10. Here we expand on the palaeoecology and bathymetry of the La Voulte biota based on the exceptional preservation of eyes bearing ommatidia in the polychelidan lobster Voulteryon parvulus Audo et al. 2014, and a unique colonization by minute brachiopods: an unusual case of association between brachiopods and a motile host11,12. This association has no direct modern counterpart, and it might be linked to the higher brachiopod diversity in the Callovian than nowadays.

Results

Morphology of eyes

The ocular incisions of Voulteryon parvulus are excavated on short expansions of the carapace reminiscent of the disposition of the eyes in Eryon Desmarest, 1817, and surround most of the ocular peduncle. The eyes have a long stalk ending in a short cylindrical section and a hemispheric cornea covered by hexagonally-packed ommatidia. Observation of facets is possible on the part of the holotype (Fig. 1) and on the counterpart of the paratype (Fig. 2).

Eyes of the holotype of Voulteryon parvulus Audo, Schweigert, Saint Martin & Charbonnier, 2014 (MNHN.F. A50708): (A,B) complete specimen, in dorsal view, under cross-polarized light (A) and interpretative line-drawing (B,C) virtual slice at the level of the eye (X-ray tomography data), arrows highlight the boundaries between the various internal structure of the eye; (D) dorsal surface of left eye showing ommatidial lenses arrays (SEM); (E) transition between hexagonal and quadrate arrays with imprints of ommatidial lenses (SEM); (F) dorsal surface of right eye showing imprints of ommatidial lenses arrays (SEM); (G) hexagonal array with imprints of ommatidial lenses (SEM); (H) quadrate array with imprints of ommatial lenses (SEM); (I) more abrupt transition between hexagonal (black asterisks) and quadrate (white asterisk) arrays with imprints of ommatidial lenses (SEM). Abbreviations: ala, anterolateral angle; b1, hepatic groove; bc, branchial carina; bi, hepatic incision; c, cervical groove; cse, short expansion of carapace; d, gastro-orbital groove; e1e, cervical groove; ei, cervical incision; fm, frontal margin; o, eye; P1, pereiopod 1 (=thoracopod 4); pc, postcervical carina; pla, posterolateral angle; pr, postrostral carina; s1-s6, pleonite 1–6. Scale bars: 5 mm (A,B) 0.5 mm (C,D,F) 50 µm (E,G–I). Images: Denis Audo (A,B, D–I) Miguel Garcia Sanz (C).

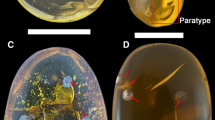

Eyes of the paratype of Voulteryon parvulus (MNHN.F.A29151): (A,B) complete specimen, in dorsal view, under cross-polarized light with part (A) and counterpart (B,C) dorsal and lateral surface of left-eye showing some preserved arrays with imprints of ommatidial lenses (SEM); (D) hexagonal array with imprints of ommatidial lenses (SEM); (E) eroded area of the eye showing what may be section of distal rhabdoms14, possibly at the transition between hexagonal (white asterisks) and quadrate arrays (black asterisks), the middle row appears to be intermediate (black and white asterisks) (SEM); (F) dorsal and lateral surface of right-eye showing some preserved arrays of ommatidial lenses (SEM); (G,H) hexagonal array of ommatidial lenses (SEM). Scale bars: 5 mm (A,B), 0.5 mm (C,F), 0.1 mm (D,G,H), 50 µm (E). Images: Denis Audo (A–E) and Ninon Robin (F–H).

Holotype

The left eye is incompletely preserved (Fig. 1A). The right eye diameter is about 0.95 mm (Fig. 1B). Some internal structures of ommatidia (crystalline cones, retina?) are probably preserved, but not recognized at the present time. On the tomographic virtual slices, we can only observe indistinct layers, so it is impossible to recognize if histological details similar to those observed on thylacocephalans10 are preserved without breaking the specimen (Fig. 1C). All the facets are made visible by the hollow traces left by the corneal lenses. This type of preservation seems frequent and can be seen in other fossil polychelidans (Fig. 3), isopods, and insects5. The eyes appear to have small hexagonal facets (~34 µm diameter) on most of their surfaces (Fig. 1D–G,I), although some square facets in nearly orthogonal array (with facets side ~24 µm long) are also visible dorsally (Fig. 1E,H,I). The dorsal patch of square facets is separated from the dorsal margin of the visual surface – adjacent to the stalk – by two rows of hexagonal facets (Fig. 1I), resulting in a sharp transition between hexagonal and square facets. In contrast, on the lateral region of the visual surface, the transition between square and hexagonal facets appears more gradual (Fig. 1E).

Small specimen of Hellerocaris falloti (Van Straelen, 1923) (MNHN.F.A50709): (A) entire specimen (SEM); (B) right eye showing imprints of ommatidial lenses (SEM); (C) imprints of ommatidial mostly in quadrate arrays, but also with some irregularities (indicated by arrows) (SEM). Scale bars: 2 mm (A), 0.5 mm (B) and 0.1 mm (C). Images: Philippe Loubry.

Paratype

The left eye diameter is about 1.15 mm (poorly preserved anteriorly) (Fig. 2A,B). As in the holotype, most of the ommatidia are hexagonally-packed and bear small hexagonal facets (~35 µm diameter) (Fig. 2C,E–H). On the part (Fig. 2A,C–E), the few ommatidia visible on the lateral region have hexagonal facets (as indicated by the imprint of the corneal lenses), although the anterior region of the eye reveals faint traces of what might be the transition between ommatidia packed in hexagonal array to a more rectilinear fashion (Fig. 2E). On the counterpart, corneal lenses are well preserved and with circular facets arranged hexagonally (Fig. 2F.H). As described for the larvae of Palaemon serratus (Pennant, 1777), it appears that packing is hexagonal, but that the corneal lenses themselves are circular13. On an eroded part of the eye (Fig. 2E), we can observe traces of ommatidia far apart from each other. This might correspond to a deeper part of the ommatidia, possibly the distal rhabdom14.

Epibionts

The holotype displays on its carapace eight complete valves, shelly remains, or attachment scars of brachiopods (Fig. 4A). The most complete brachiopod, exhibiting a well-preserved ventral valve, is attached on the right side of the lobster near the median line, immediately posterior to the cervical groove (Fig. 4B). Three other epibiotic structures may correspond to the discoid attachment scars of dorsal valves. They occur near the ocular incision (Fig. 4A) anterior (Fig. 4C) and posterior (Fig. 4D) to the postcervical groove, on the left side of the specimen. Two other scars, located posterior to the branchiocardiac groove on the anterior right side of the carapace (Fig. 4E) and near the posterior margin (Fig. 4F), evoke shell-shaped surface swellings that would correspond to highly abraded ancient valves. These remains range from 180 to 500 µm in diameter.

Thecidean brachiopods attached to the holotype (MNHN.F. A50708) of Voulteryon parvulus: (A) locations of eight brachiopod shelly remains; (B) ventral valve of the most complete brachiopod; (C), a second valve; (D) two cemented valves remains or attachment scars; (E,F) shell-shaped swellings that could correspond to damaged previously attached valves. Scale bars = 5 mm (A); 0.2 mm (B–F). Images: Denis Audo (A,B) and Ninon Robin (C–F).

The brachiopods attached to the specimen of Voulteryon parvulus have a characteristic sub-circular to sub-triangular outline (Fig. 4B,C), a feature typical of thecideid brachiopods15,16. Unfortunately, the diagnostic characters used in the systematics of these brachiopods are generally located on their dorsal (=brachial) valves and not ventral (=pedicle) ones, which are preserved in the specimens here discussed. In addition, the diameters of the ventral valves (or their traces – Fig. 4D–F) suggest that these brachiopods were juveniles. Due to their preservation and development stage, precise determination of specimens is impossible. Indeed, according to Baker17, early juveniles are not only less common than adults in the fossil record, but they are also more difficult to identify16,17,18. Nevertheless, the right antero-lateral portion of the best available specimen (Fig. 4B) preserves the exposed edge, which is typical of the ventral valves of early juvenile thecideoid shell16. Based on such criteria we consider these specimens as Rioultina-like forms. These thecideoid brachiopods were abundant during the Jurassic, with a range spanning from late Bathonian to late Oxfordian18,19.

Discussion

Size of eyes and ommatidia

Representatives of Voulteryon parvulus and other small polychelidans have small eyes and facets when compared to larger polychelidans (Fig. 5). These characteristics are unlikely to be directly linked to the environment, as Audo et al.5 showed a dominant positive correlation of eye and facet size with the carapace length. A small phylogenetic effect is possible, since eryonids tend to have smaller eyes than coleiids, the other main polychelidan clade5.

Statistical analysis of the size of the eye and ommatidia of Voulteryon parvulus compared to those of other fossil polychelidans and arthropods: (A) relation between the size of carapace and diameter of the eye in polychelidan lobsters. (B) relation between the size of the eye and of ommatidia in polychelidan lobsters, with a comparison to the eyes of supposed phyllosoma larvae from Santana (Sant.) and a thylacocephalan (Dollocaris ingens) from La Voulte. The original measurements are in micrometers. Abbreviations: holo, holotype; para, paratype; hex, hexagonal ommatidia; Sant., phyllosoma from the Cretaceous Santana Formation sq, square ommatidia;. Original data for V. parvulus from the present study; for polychelidans, from Audo et al.5; for phyllosoma, from Tanaka et al.34; for Dollocaris ingens, from Vannier et al.10.

Interpretation of ommatidia packing and facet shape

Hexagonal facets

The hexagonal facets packed in hexagonal lattice of V. parvulus are typical of apposition eyes, refractive and parabolic superposition eyes.

If we consider the apposition hypothesis: Eyes with apposition optics correspond to the simplest type of compound eyes, are a plesiomorphic condition for eucrustaceans, and are present in fossil and extant decapod larval stages13,20,21. Adult decapods in most shrimp, lobster, galatheoid anomuran, and ancient brachyuran groups, however, share a unique reflecting superposition visual system coupled to square-shaped ommatidial cornea, not seen in other marine eucrustaceans22,23,24,25. Noticeably, a number of decapod lineages have independently retained the larval apposition eyes20,26, or have evolved refractive or parabolic superposition eyes while retaining a hexagonal packing27. Previously, Rogeryon oppeli (Woodward, 1866) was the only polychelidan considered to have hexagonal facets (most likely apposition eyes) retained due to paedomorphic, more precisely neotenic evolution5. Voulteryon parvulus is probably also a paedomorphic form28, so it is more parsimonious to consider that its hexagonally-packed ommatidia correspond to larval apposition optics retained in adulthood as in R. oppeli. In contrast to R. oppeli, however, the adults are smaller in V. parvulus, and either progenesis or a combination of progenesis and neoteny may have occurred in this case. Another process might explain the presence of apposition eyes; in small scarabeoidea beetle, the eye is sometimes so small (less than 0.6 mm in diameter) that superposition optics cannot be accommodated29. For V. parvulus, such an interpretation is unlikely because: (1) a small specimen of Palaeopentacheles roettenbacheri (Fig. 3) has smaller eyes which are probably of the reflective superposition type5 yet are smaller than those of V. parvulus and (2) V. parvulus has eyes that are more than 50% bigger than the biggest eyes of the aforementioned scarabeoidea.

It is also possible, yet probably less parsimonious, that V. parvulus, and perhaps also Rogeryon oppeli5, had a type of superposition optics that did not require square facets: refractive or parabolic superposition optics. From the fossil alone we cannot distinguish between these two options. However, while we can propose a simple evolutionary scenario explaining the presence of apposition optics in an adult by heterochronous retention of the larval apposition eyes, having refracting or parabolic superposition optics, although likely, is less parsimonious than the retention of apposition optics.

Square facets

The eyes of the holotype (and likely the paratype) show small patches of square-facetted ommatidia (Fig. 1E,H). These facets with rectilinear packing are strongly reminiscent to those seen in decapods with reflective superposition eyes26 (although this shape can sometimes occur in parabolic and refracting superposition eyes27,30). These ‘mirror’ eyes are well suited for dim-light conditions, and are commonly seen across nocturnal or deep-water decapod taxa31.

Association of square and hexagonal facets

The combination of two types of structured arrays is unusual: in polychelidans, most documented arrays are square (9 species), with only one other example of hexagonal arrays5. Even within decapods, eyes combining hexagonal and square facets are extremely rare. They have only been reported in a handful of taxa: (1) the post-zoeal stage with all pleonal appendages of the hydrothermal vent caridean shrimp Rimicaris exoculata Williams & Rona, 198632; (2) the adult benthesicymid shrimp30; (3) isolated decapod fossil eyes, supposedly of a phyllosoma larva from the Santana Group33; and (4) at least one extinct and three extant brachyuran species34 (Luque, personal observation). Yet, it is unclear whether such a combination of facet shape and packing implies that two discrete and functional visual systems are present (which may need different underlying optical neuropiles), or if it may occur as the outcome of the packing, size, and position of marginal facets being accreted to the eye.

Another fossil with an apparent combination of facet types is the polychelidan lobster Hellerocaris falloti (Van Straelen, 1923), also from La Voulte (Fig. 3). In H. falloti, most of the facets are square and packed orthogonally as in reflecting superposition eyes, although some facets are hexagonal or irregular (Fig. 3C). However, the non-square facets in H. falloti may just be a local packing artifact rather than a true regionalization of the eye. Contrary to H. falloti, in V. parvulus hexagonal facets are the dominant type, and may correspond to larval apposition optics retained in later instars, with the discrete squarish facets likely representing either a) an artefact of the packing, or b) a transition towards the adult reflecting superposition eye type seen across most of polychelidans from La Voulte.

In general, the number of ommatidia increases with growth, and the ommatidia may be inserted from a dorsal accretion zone, which points to a gradual development of the adult eye from the larval eye13,35. In the case of mantis shrimps, the adult optics of the eye arise on the ocular peduncle separated from the larval optics of the eye, and pushe it aside as they develop35,36. In the case of the gradual development of the eye, it seems that ommatidia optics are “pre-adapted” to their adult forms: light is reflected or refracted as in superposition optics, but the lack of clear zone and adaptations of the rhabdom force the eye to function as an apposition eye. This scenario is similar to that proposed by Tanaka et al.33 to explain the occurrence of a patch of square facets on the anterior part of isolated fossil eyes.

Another interesting possibility is presented by benthesicymid shrimps, where the visual surface can be composed of more than one third of square facets, the rest being hexagonal. It has been proposed that these square facets are an evolutionary relict of ancestral reflective superposition optics30. Such a case would not be too surprising in the case of V. parvulus since the presence of reflective superposition optics is the ancestral condition in polychelidan lobsters is the presence of reflective superposition optics.

Visual capacities of the eyes in a deep-water environment

Voulteryon parvulus differs from most other polychelidans and glypheidans from La Voulte, which are very likely to possess reflective superposition eyes5 (see also Charbonnier et al.37, Fig. 337). Besides, due to its small size, the corneal lenses cannot compensate the absence of superposition optics by their size (larger ommatidial lenses can collect more light, as in deep-sea isopods or anomura, which can have large ommatidial lenses25,38 – but also consider that small ommatidial lenses in V. parvulus are expected, since size of ommatidial lenses is mostly proportional to the size of the animal5). The pooling of ommatidia signal as it occurs in deep-water hyperiid amphipods39 also seems unlikely, since hyperiids have bilobed eyes (i.e., one lobe with a higher resolution and another with higher sensitivity) absent in V. parvulus or other polychelidan lobsters. Yet, we cannot exclude other processes that would increase dramatically the sensitivity of the eye such as temporal summation (photons are collected over longer periods of time, at the expense of temporal resolution) or neural resolution (adjacent rhabdoms combine part of their signal by neural connection40, herein impossible to study).

From the available data, we infer that the eyes of V. parvulus were likely poorly adapted to dim-light environments, as expected from eyes of the apposition type (note however that some possible mechanisms to increase sensitivity such as tapetum or rhabdom adaptations cannot be observed). Yet, whether the small square-facetted area in the eyes of V. parvulus functioned as superposition optics or not is unlikely, since superposition optics necessitate numerous ommatidia to collect the light optimally. Contrary to most other polychelidans and glypheidans in La Voulte, and similarly to Rogeryon oppeli, V. parvulus might have been better suited for bright-light conditions. This is surprising in a disphotic palaeoenvironment as it has been proposed by Charbonnier et al.9,41 for La Voulte. In fact, the size of corneal facets and apposition optics of V. parvulus are similar to that of the co-occurring thylacocephalan crustacean Dollocaris ingens Van Straelen, 1923, which was considered to be adapted to well-illuminated environments.

We also acknowledge that it is possible that V. parvulus had a type of superposition optics that does not require square facets. i.e., refractive superposition, parabolic superposition. As above explained, this hypothesis is slightly less parsimonious, but it would however explain the presence of V. parvulus in a supposedly deep-water palaeoenvironment.

Ontogeny

Despite its small size (holotype carapace maximum length = 10.0 mm, paratype carapace maximum length = 9.1 mm), Voulteryon parvulus was at a sexually mature size as attested by the development of the ovaries in the holotype28, and thus considered as paedomorphic. The development of the visual surface in V. parvulus herein documented reinforces the interpretation that V. parvulus was paedomorphic. If we consider that its ommatidial array is ontogenetically intermediate between larval and adult eye, it is surprising to observe such a late replacement of apposition optics. Even small juvenile specimens of Palaeopentacheles roettenbacheri (Münster, 1838) and Hellerocaris falloti have fully developed reflective superposition eyes5. The apposition optics of the eye of V. parvulus might therefore represent a case of neoteny, just as in Rogeryon oppeli, with the added minute size of specimens. It is possible that despite being sexually mature, V. parvulus had not finished its growth. Indeed, other eucrustaceans continue to grow after their sexual maturity42.

Epibionts

Age of the epibionts

Contrary to the well documented size-frequency patterns in fossil and modern brachiopods43,44,45, data reporting precise size/age ratio are far less available, especially for very young shell stages. Indeed, very small brachiopods are rarely recovered as fossils46 and modern early instars are difficult to survey because of their small size. They often display transparent valves, and have a propensity for cryptic settlement47.

The age of the epibiotic brachiopods on V. parvulus (Fig. 4) can be assessed from measurements obtained from communities of modern benthic and subtidal temperate species (Scotland and New Zealand, respectively), and on one Antarctic species whose growth occurs much slower than that of temperate ones. Extrapolating data obtained on post-larval terebratulids48, we infer that the largest fossil brachiopods associated to V. parvulus attached and grew to their size in a timeframe of more than a month (500 µm reached in 43 days).

The exquisite preservation of the polychelidan host with appendages and delicate structures such as the eyes, all preserved in connection but above the internal organs fossilized in 3D28, implies a very short post-mortem exposure of its carcass. The inferred rapid burial of the host body (or displacement of the carcass to an environment unfavourable to many organisms) contradicts any post-mortem attachment/growth of the brachiopods that would have lasted more than a month. Thus, the brachiopods most likely colonized V. parvulus while alive, further supported by the location of the thecideoids on the crustacean, all attached to the carapace and none on the more articulated segments of the pleon (Fig. 4). This selective distribution evokes a biological elimination of the brachiopods. Indeed, attachment of the young epibionts to the pleonites should have been limited by the constant movements along the pleonal articulations.

Rarity of the association

Due to their sessile habit, brachiopods may be expected to live onto many other hard-bodied organisms. However, cases of fossil brachiopods identified as ancient ectosymbionts are few. Most examples known so far correspond to Cambrian associations from the Burgess shale-type deposits and Mesozoic sponge-reef foulings. Indeed, symbiotic lingulate brachiopods are known to have colonized the frond of the Cambrian algae-like organisms Malongitubus49 and the spicules of sponges (Paterinata and Kutorginata)50. Nisusiid brachiopods are known to have been living in commensal of the motile Wiwaxia corrugata Walcott, 1911, attached to the dorsal spine of these Cambrian possible molluscs12. They are also reported as ectosymbionts of other lophophorates, like other brachiopods from the Cambrian of China51 and Canada52 or the Silurian of England53; but also possibly attached to the disk of the middle Cambrian eldonioid Rotadiscus guizhouensis Zhao & Zhu, 1994, whose systematic nature and life habits remain poorly understood (semi-motile?)54. Spiriferid brachiopods attached on the proximal part of echinoderms spicules from the Carboniferous of Texas were also identified as likely commensals of their hosts55. From the Jurassic, some studies attempted to demonstrate the syn-vivo nature of some large scale foulings-like on sclerosponges19,56, bivalves57 or other brachiopods (lacunosellids)19.

Evidences of clear post-mortem associations have also been identified; they involve a “stem-group” of brachiopod on the carcasses of the Cambrian arthropod Sidneyia inexpectans Walcott, 191158 but also much more recent thecideoids on the inner mould of Paleocene crabs59.

Consequently, confident reports of fossil symbiotic brachiopods on motile organisms were hitherto restricted to the colonization of Wiwaxiidae (possible molluscs), and to typical Burgess-like environments and fauna. The association of Jurassic thecideoid brachiopods and a polychelidan lobster here described corresponds to novel association between brachiopods and a motile benthic host (see Table 1 in the Supplementary Information). The colonisation of such a substrate may have provided various benefits to the thecideoids: (1) obtaining an attachment on a hard substratum; (2) avoiding being silted by sedimentary supplies; (3) access to an increased food supply for such filter-feeders provided by the locomotion of their host; (4) obtaining a favoured dispersion of the larvae, and thus a wider range of potential substrates to colonise60.

In the Ravin des Mines, where the Lagerstätte was deposited and V. parvulus was discovered, the substrate was soft (see Geological context in the Supplementary Information). Therefore, at this place, thecideoids were more likely to attach to other organisms. On the other hand, the Ravin du Chénier, a fossil locality without exceptional preservation, contains a rather rich sessile bathyal fauna involving a diversity of hexactinellid sponges and crinoids, ranging from the disphotic to aphotic portion of the continental slope, suggesting the presence of a hard substrate8,41. Surprisingly, in the latter, epibionts including thecideoids are rare41, and this fouling competition must have been inferior to that occurring in circalittoral environments. Given that the brachiopods presence should not have hindered the host fitness in any significant way, a commensal and facultative interaction between these thecideoids and V. parvulus can be inferred. This relation displays no counterpart reported in modern environment. That uniqueness could result of the under-examination of modern marine arthropods for their epibionts, like observed for other taxa (e.g. foraminiferans and bivalves60,61, but also of the reduced diversity of extant brachiopods.

Palaeobiology of the epibiont

Thecideoid brachiopods are small cementing articulated cavity-dwelling forms. In modern environments, they occupy dim-light environments of cryptic habitats (=cryptobionts or coelobites62 – sensu Kobluk63), and the most probably colonised similar habitats in the past44,64,65,66,67). More precisely, in modern environments, they are typical for shallow water crevices, submarine caves, undersides of sponges and/or corals or other marine invertebrates and are widely distributed in tropical and subtropical seas64,68,69,70 at a depth ranging from a few meters to about 150 m68,71,72,73,74,75,76). In the fossil record, thecideoid brachiopods often used lower surfaces of sponges as hard substrate19,56,77, coral-reef cavities78, empty shells on the sea floor79, and small cryptic spaces resulting from the disintegration of hardgrounds62,80,81,82,83,84. They also incrusted surfaces of Jurassic brachiopods (Oxfordian lacunosellids19), bivalves (Kimmeridgian oysters Actinostreon85; Callovian Ctenostreon57), sclerosponges (Oxfordian Neuropora19), oncoids (Bajocian86 and Bathonian87) or bored cobbles83,88. Exceptionally, some extant thecideoid brachiopods live in deep-water environments at depths between 400 and 1000 m76.

The cavity-dwelling strategies of cryptic brachiopods have been used earlier, not only in Mesozoic times (e.g. Triassic Thecospira89,90,91), but probably also in the Palaeozoic (e.g., Silurian Leptaenoidea and Liljevallia92, Devonian Davidsonia93), which have close phylogenetic relationships with thecideoid brachiopods94. Therefore, these thecideoid epibionts on the carapace of V. parvulus are a rare example of using mobile benthic animals as hard substratum for their colonisation. This contrasts with the standard occurrences of these brachiopods on sessile benthic invertebrates or pieces of rocks. Additionally, their photophobic character indicates at least dark palaeoenvironments during incrustations and can be used to infer bathymetric conditions of their host, deeper than photic zone of the sea floor.

Conclusion

The exceptional preservation of Voulteryon parvulus from the Middle Jurassic of La Voulte, France, including the presence of compound eyes bearing facets (this work), a unique example of a syn-vivo association between epibiont brachiopods and crustaceans (this work), and ovaries28, gives new insights on the palaeoecology of this polychelidan lobster and the La Voulte Lagerstätte.

The epibiont brachiopods of V. parvulus generally inhabit dim-light environments, which is congruent with previous hypothesis by Charbonnier et al.41 and Charbonnier8 of deep-water, low-lit conditions during the deposition of the La Voulte Lagerstätte. Surprisingly, the most parsimonious interpretation of the surface of the eyes in V. parvulus suggests limited capacity for vision in low-light conditions. These two apparently opposed results are difficult to explain with certainty. One hypothesis is that La Voulte Lagerstätte was not as deep as what seems to be indicated by the geology and sponges in the nearby Chénier ravine (hypotheses of Charbonnier et al.41 and Charbonnier8). This would agree with Vannier et al.10, who suggested more lit conditions based on the presence of the large-eye predatory arthropod Dollocaris ingens. Yet, the presence of thecideoid brachiopods on V. parvulus strongly indicates dim-light conditions: either due to the depth in La Voulte or to the microenvironment of crevices in a shallower environment.

Voulteryon parvulus was a mobile organism, and the geology in the vicinity of La Voulte is dominated by numerous faults that probably created an irregular bathymetry at the time of deposition of the La Voulte Lagerstätte. We therefore propose two additional hypotheses that could explain all observations (Fig. 6):

-

1.

Nature of the eyes: Adults of V. parvulus had refractive or parabolic superposition eyes, so they were capable of living in a dim-light environment. The only problem of this hypothesis is that it requires an independent evolution of parabolic or refractive superposition eyes from either reflective superposition or apposition eyes.

-

2.

Displacement or natural migration: V. parvulus may have lived in a more well-illuminated environment (as suggested by its eyes); which probably would have been different from the one in La Voulte. Since thecideoid brachiopods prefer crevices or dim light, it is possible that V. parvulus used to hide in rock crevices; V. parvulus was then either flushed to the deposition environment of La Voulte, or, more probably, La Voulte could have been a reproductive ground for V. parvulus28. This last suggestion seems plausible but opens the question: did V. parvulus spend enough time in the depth of La Voulte for the fixation and growth of the epibionts? Unfortunately, too little is known about the reproductive behaviour of extant polychelidans95,96 to compare it with their fossil relatives.

Visual depiction of the palaeoenvironment of Voulteryon parvulus: Voulteryon parvulus lived probably in a shallow-water, well-illuminated environment, perhaps in crevices (1), explaining the presence of its epibionts and perhaps used to mate or lay its eggs in the La Voulte Lagerstätte (2). Note that due to the presence of numerous faults, the palaeotopography of the vicinity of the La Voulte Lagerstätte was quite accidented. Therefore, Voulteryon parvulus did not have to move over great distances to reach deeper waters. Similarly, Dollocaris ingens could as well move or be transported in La Voulte deposition environment from a nearby shallower palaeoenvironment.

Transportation of the thylacocephalan Dollocaris ingens, facilitated by its nektobenthic lifestyle10, and the irregular palaeobathymetry in the La Voulte area, could also explain the apparent mismatch between geological data and the ecology of some arthropods as suggested by their exceptionally preserved visual systems. La Voulte biota clearly combines the influence of multiple palaeoenvironments, as expected from the complex local geology.

Material and Methods

Material

We study the only two known specimens of Voulteryon parvulus (holotype: MNHN-F.A50708; paratype: MNHN.F.A29151), from the La Voulte-sur-Rhône Lagerstätte, housed in the palaeontology collection of the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle (MNHN.F specimens). Both specimens are three-dimensionally preserved inside sideritic nodules and show very fine anatomical structures1,28. The holotype consists only of the part, and the paratype consists of both part and counterpart.

Imagery techniques

Global views of the holotype and paratype of Voulteryon parvulus were done using a cross-polarized light setup97,98) coupled to image stacking. Colour detailed views of the epibionts and eyes on the holotype were obtained with a 24 × 36 mm digital SLR equipped with a x10 microscope objective. The holotype was micrographed using a Hitachi Analytical Table Top Scanning Electron Microscope. The paratype was micrographed using a Tescan SEM (VEGA II LSU) linked to an X-ray detector SD3 (Bruker) (Direction des Collections, MNHN, Paris).

Additionally, we used the virtual slices and the reconstruction of the ventral surface of the holotype by Jauvion et al.28, reconstructed using the VG-Studio MAX 2.2 (© Volume Graphics) software on X-Ray Tomography (XTM, CT-Scan) data (voxel size = 9.55 µm, 2007 virtual slices), acquired at the AST-RX platform (USM 2700, MNHN) on a v/tome/x 240 L tomograph (GE Sensing & Inspection Technologies Phoenix X/ray) and equipped with a microfocus 240 kV/320 W tube delivering a current/voltage of 485 mA/95 kV.

Data Availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Information.

References

Audo, D., Schweigert, G., Saint Martin, J.-P. & Charbonnier, S. High biodiversity in Polychelida crustaceans from the Jurassic La Voulte-sur-Rhône Lagerstätte. Geodiversitas 36, 489–525, https://doi.org/10.5252/g2014n4a1 (2014).

Galil, B. S. Crustacea Decapoda: review of the genera and species of the family Polychelidae Wood-Mason, 1874 in Résultats des campagnes MUSORSTOM, Volume 21. Mémoir. Mus natl. Hist. nat. 184 (ed. Crosnier, A.) 285–387 (2000).

Ahyong, S. T. The Polychelidan Lobster: Phylogeny and Systematics (Polychelida: Polychelidae) in Decapod Crustacean Phylogenetics. Crustacean Issues 18 (eds Martin J. W., Crandall K. A. & Felder D. L.) 369–396, https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420092592-c19 (Taylor & Francis, 2009).

Beurlen, K. D. B. der Tiefsee. Natur und Museum 61, 269–278 (1931).

Audo, D. et al. On the sighted ancestry of blindness – exceptionally preserved eyes of Mesozoic polychelidan lobsters. Zool. Letters 2, 1–20, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40851-016-0049-0 (2016).

Audo, D., Charbonnier, S. & Krobicki, M. Rare fossil polychelid lobsters in turbiditic palaeoenvironments. J. Syst. Palaeontol. 16, 1017–1036, https://doi.org/10.1080/14772019.2017.1359690 (2018).

Audo D., Hyžný M. & Charbonnier S. The early polychelidan lobster Tetrachela raiblana and its impact on the homology of carapace grooves in decapod crustaceans. Contrib. zool. 87, 41–57 (2018).

Charbonnier, S. Le Lagerstätte de La Voulte: un environnement bathyal au Jurassique. Mémoir. Mus. natl. Hist. nat. 199, 1–272 (2009).

Charbonnier, S., Vannier, J., Hantzpergue, P. & Gaillard, C. Ecological significance of the arthropod fauna from the Jurassic (Callovian) La Voulte Lagerstätte. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 55, 111–132, https://doi.org/10.4202/app.2009.0036 (2010).

Vannier, J., Schoenemann, B., Gillot, T., Charbonnier, S. & Clarkson, E. Exceptional preservation of eye structure in arthropod visual predators from the Middle Jurassic. Nat. Commun. 7, 10320, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10320 (2016).

Conway-Morris, S. The Middle Cambrian metazoan Wiwaxia corrugata (Matthew) from the Burgess Shale and Ogygopsis Shale, British Columbia, Canada. Philos. Tr. R. Soc. S.-B 307, 507–582, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1985.0005 (1985).

Topper, T. P., Holmer, L. E. & Caron, J. B. Brachiopods hitching a ride: an early case of commensalism in the middle Cambrian Burgess Shale. Sci. Rep. 4, 6704, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06704 (2014).

Fincham, A. A. Ontogeny and optics of the eyes of the common prawn Palaemon (Palaemon) serratus (Pennant, 1777). Zool. J. Linn. Soc.-Lond. 81, 89–113, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1984.tb01173.x (1984).

Meyer-Rochow, V. B. Larval and ault eye of the Western Rock Lobster (Palinurus longipes). Cell Tiss. Res. 162, 439–457 (1975).

Baker, P. G. Thecideida in Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, part H, Brachiopoda (Revised) Volume 5 (ed. Kaesler, R.) 1938–1964 (Geological Society of America, 2006).

Baker, P. G. & Carlson, S. J. The early ontogeny of Jurassic thecideoid brachiopods and its contribution to the understanding of thecideoid ancestry. Palaeontology 53, 654–667 (2010).

Baker, P. G. New evidence of a spiriferide ancestor for the Thecideidina (Brachiopoda). Palaeontology 27, 857–866 (1984).

Baker, P. G. & Wilson, M. A. The first thecideide brachiopod from the Jurassic of North America. Palaeontology 42, 887–895 (1999).

Krawczyński, C. The Upper Oxfordian (Jurassic) thecideide brachiopods from the Kujawy area, Poland. Acta Geol. Pol. 58, 395–406 (2008).

Porter, M. L. & Cronin T. W. A shrimp’s eye view of evolution: how useful are visual characters in Decapod phylogenetics? in Decapod Crustacean Phylogenetics. Crustacean Issues 18 (eds Martin J. W., Crandall K. A. & Felder D. L.) 183–195 (Taylor & Francis, 2009).

Luque, J. A puzzling frog crab (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura) from the Early Cretaceous Santana Group of Brazil: frog first or crab first? J. Syst. Palaeontol. 13, 153–166, https://doi.org/10.1080/14772019.2013.871586 (2015).

Scholtz, G. & McLay, C. L. Is the Brachyura Podotremata a monophyletic group? In Decapod Crustacean Phylogenetics. Crustacean Issues 18 (eds Martin J. W., Crandall K. A. & Felder D. L.) 417–435 (Taylor & Francis, 2009).

Tudge, C. C., Asakura, A. & Ahyong, S. T. Infraorder Anomura MacLeay, 1838, In Treatise on Zoology-Anatomy, Taxonomy, Biology. The Crustacea, 9B (70) (eds Schram, F. R. & Von Vaupel Klein, J. C.) 221–333 (Brill, 2012).

Gaten, E., Moss, S. & Johnson, M. L. The reniform reflecting superposition compound eyes of Nephrops norvegicus: optics, susceptibility to light-induced damage, electrophysiology and a ray tracing model. Adv. Mar. Biol. 64, 107–148, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-410466-2.00004-2 (2013).

Eguchi, E., Dezawa, M. & Meyer-Rochow, V. B. Compound eye fine structure in Paralonis multispina Benedict, an Anomuran half-crab from 1200 m depth (Crustacea; Decapoda; Anomura). Biol. Bull. 192, 300–308 (1997).

Cronin, T. W. & Porter, M. L. Exceptional Variation on a Common Theme: The Evolution of Crustacean Compound Eyes. Evolution: Education and Outreach 1, 463–475, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12052-008-0085-0 (2008).

Nilsson, D. E. A new type of imaging optics in compound eyes. Nature 332(6159), 76–78, https://doi.org/10.1038/332076a0 (1988).

Jauvion, C., Audo, D., Charbonnier, S. & Vannier, J. Virtual dissection and lifestyle of a 165-million-year-old female polychelidan lobster. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 45, 122–132, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asd.2015.10.004 (2016).

Meyer-Rochow, V. B. & Gál, J. Dimensional limits for arthropods eyes with superposition optics. Vison Res. 44, 2213–2223 (2004).

Nilsson, D. E. Three unexpected cases of refracting superposition eyes in crustaceans. J. Comp. Physiol. A 167, 71–78, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00192407 (1990).

Cronin, T. W. Optical design and evolutionary adaptation in crustacean compound eyes. J. Crustacean Biol. 6, 1–23, https://doi.org/10.1163/193724086X00686 (1986).

Gaten, E., Herring, P. J., Shelton, P. M. J. & Johnson, M. L. Comparative morphology of the eyes of postlarval bresiliid shrimps from the region of hydrothermal vents. Biol. Bull. 194, 267–280, https://doi.org/10.2307/1543097 (1998).

Tanaka, G., Smith, R. J., Siveter, D. J. & Parker, A. R. Three dimensionally preserved decapod larval compound eyes from the Cretaceous Santana Formation of Brazil. Zool. Sci. 26, 846–50, https://doi.org/10.2108/zsj.26.846 (2009).

Luque, J. et al. Exceptional preservation of mid-Cretaceous marine arthropods and the evolution of novel forms via heterochrony. Sci. Adv. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aav3875 (in press).

Cronin, T. W. & Jinks, R. N. Ontogeny of vision in marine crustaceans. Am. Zool. 41, 1098–1107, https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/41.5.1098 (2001).

Williams, B. G., Greenwood, J. G. & Jillen, J. B. Seasonality and duration of the developmental stages of Heterosquilla tricarinata (Claus, 1871) (Crustacea: Stomatopoda) and the replacement of the larval eye at metamorphosis. B. Mar. Sci. 36, 104–114 (1985).

Charbonnier, S., Garassino, A., Schweigert, G. & Simpson, M. A worldwide review of fossil and extant glypheid and litogastrid lobsters (Crustacea, Decapoda, Glypheoidea). Mémoir. Mus. natl. Hist. nat. 205, 1–304 (2013).

Nilsson, D.-E. & Nilsson, H. L. A crustacean compound eye adapted for low light intensities (Isopoda). J. Comp. Physiol 143, 503–510, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00609917 (1981).

Land, M. F. Optics of the eyes of Phronima and other deep-sea amphipods. J. Comp Physiol 145, 209–226, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00605034 (1981).

Land, M. F., Nilsson, D.-E. Animal eyes: second edition. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199581139.003.0007 (Oxford University Press, 2012).

Charbonnier, S., Vannier, J., Gaillard, C., Bourseau, J.-P. & Hantzpergue, P. The La Voulte Lagerstätten (Callovian): Evidence for a deep water setting from sponge and crinoid communities. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. 250, 216–236, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.03.013 (2007).

Hartnoll, R. G. Strategies of crustacean growth. In Papers from the conference of the biology and evolution of Crustacea. Australian Museum Memoir 18 (ed. Lowry J. K.), 121–131 (1983).

Brookfield, M. E. The life and death of Torquirhynchia inconstans (Brachiopoda, Upper Jurassic) in England. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. 13, 241–259, https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-0182(73)90027-8 (1973).

Surlyk, F. Morphological adaptations and population structures of the Danish Chalk brachiopods (Maastrichtian, Upper Cretaceous). Biol. Skr. Dan. Vid. Selsk 19, 1–57 (1972).

West, R. R. Life assemblage and substrate of Meekella striatocostata (Cox). J. Paleontol. 51, 740–749 (1977).

Boucot, A. J. Life and death assemblages among fossils. Am. J. Sci. 251, 25–40, https://doi.org/10.2475/ajs.251.1.25 (1953).

Collins, M. J. Growth rate and substrate-related mortality of a benthic brachiopod population. Lethaia 24, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1502-3931.1991.tb01175.x (1991).

Doherty, P. J. A demographic study of a subtidal population of the New Zealand articulate brachiopod Terebratella inconspicua. Mar. Biol. 52, 331–342, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00389074 (1979).

Wang, H. et al. Peduncular attached secondary tiering acrotretoid brachiopods from the Chengjiang fauna: Implications for the ecological expansion of brachiopods during the Cambrian explosion. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. 323, 60–67, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2012.01.027 (2012).

Conway-Morris, S. & Whittington, H. B. Fossils of the Burgess shale: a national treasure in Yoho National Park. British Columbia. Geol. Surv. Canada Misc Report 43, 1–31 (1985).

Zhang, Z., Han, J., Wang, Y., Emig, C. C. & Shu, D. Epibionts on the lingulate brachiopod Diandongia from the Early Cambrian Chengjiang Lagerstätte. South China. P. Roy. Soc. Lon B Bio 277, 175–181, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.0618 (2010).

Moysiuk, J., Smith, M. R. & Caron, J. B. Hyoliths are Paleozoic lophophorates. Nature 541(7637), 394–397, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature20804 (2017).

Sutton, M. D., Briggs, D. E., Siveter, D. J. & Siveter, D. J. Silurian brachiopods with soft-tissue preservation. Nature 436(7053), 1013–1015, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03846 (2005).

Dzik, J., Zhao, Y. & Zhu, M. Mode of life of the Middle Cambrian eldonioid lophophorate Rotadiscus. Palaeontology 40, 385–396 (1997).

Schneider, C. L. Hitchhiking on Pennsylvanian echinoids: epibionts on Archaeocidaris. Palaios 18, 435–444, https://doi.org/10.1669/0883-1351(2003)018%3C0435:HOPEEO%3E2.0.CO;2 (2003).

Palmer, T. J. & Fürsich, F. T. Ecology of sponge reefs from the Upper Bathonian of Normandy. Palaeontology 24, 1–23 (1981).

Zatoń, M., Wilson, M. A. & Zavar, E. Diverse sclerozoan assemblages encrusting large bivalve shells from the Callovian (Middle Jurassic) of southern Poland. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. 307, 232–244, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2011.05.022 (2011).

Holmer, L. E. & Caron, J. B. A spinose stem group brachiopod with pedicle from the Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale. Acta Zool. 87, 273–290, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-6395.2006.00241.x (2006).

Jakobsen, S. L. & Feldmann, R. M. Epibionts on Dromiopsis rugosa (Decapoda: Brachyura) from the Late Middle Danian limestones at Fakse quary, Denmark: novel preparation techniques yield amazing results. J. Paleontol. 78, 953–960, https://doi.org/10.1666/0022-3360(2004)078<0953:EODRDB>2.0.CO;2 (2004).

Robin, N., Charbonnier, S., Bartolini, A. & Petit, G. First occurrence of encrusting nubeculariids (Foraminifera) on a mobile host (Crustacea, Decapoda) from the Upper Jurassic Eichstätt Lagerstätte, Germany: A new possible relation of phoresy. Mar. Micropaleontol. 104, 44–52, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2013.09.001 (2013).

Robin, N. et al. Bivalves on mecochirid lobsters from the Aptian of the Isle of Wight: Snapshot on an Early Cretaceous palaeosymbiosis. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. 453, 10–19, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.03.025 (2016).

Schlögl, J., Michalík, J., Zágoršek, K. & Atrops, F. Early Tithonian serpulid-dominated cavity-dwelling fauna, and the recruitment pattern of the serpulid larvae. J. Paleontol 82, 382–392, https://doi.org/10.1666/06-127.1 (2008).

Kobluk, D. R. Cryptic faunas in reefs: Ecology and geologic importance. Palaios 3, 379–390, https://doi.org/10.2307/3514784 (1988).

Pajaud, D. Monographie des thécidées (brachiopodes). Mém. S. Géo. F. 112, 1–349 (1970).

Nebelsick, J. H., Bassi, D. & Rasser, M. W. Cryptic relicts from the past: Palaeoecology and taphonomy of encrusting thecideid brachiopods in Paleogene carbonates. Ann. Naturhistorischen Mus Wien A 113, 525–542 (2011).

Simon, E. & Hoffmann, J. Discovery of Recent thecideide brachiopods (Order: Thecideida, Family: Thecideidae) in Sulawesi, Indonesian Archipelago, with implications for reproduction and shell size in the genus Ospreyella. Zootaxa 3694, 401–433 (2013).

Logan, A., Hoffmann, J. & Lüter, C. Checklist of Recent thecideoid brachiopods from the Indian Ocean and Red Sea, with a description of a new species of Thecidellina from Europa Island and a re-description of T. blochmanni Dall from Christmas Island. Zootaxa 4013(2), 225–234 (2015).

Pajaud, D. Écologie des Thécidées. Lethaia 7, 203–218, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1502-3931.1974.tb00897.x (1974).

Lüter, C., Wörheide, G. & Reitner, J. A new thecideid genus and species (Brachiopoda, Recent) from submarine caves of Osprey Reef (Queensland Plateau, Coral Sea, Australia). J. Nat. Hist. 37, 1423–1432, https://doi.org/10.1080/00222930110120971 (2003).

Bitner, M. A. & Logan, A. Recent Brachiopoda from the Mozambique-Madagascar area, western Indian Ocean. Zoosystema 38, 5–41, https://doi.org/10.5252/z2016n1a1 (2016).

Logan, A. The Recent Brachiopoda of the Mediterranean Sea. Bulletin de l’Institut Oceanographique Fondation Albert I, Prince de Monaco 72(1434), 1–112 (1979).

Cooper, G. A. New Brachiopoda from the Indian Ocean. SM C. Paleob. 16, 1–43, https://doi.org/10.5479/si.00810266.16.1 (1973).

Cooper, G. A. Brachiopoda from the Southern Indian Ocean (Recent). SM C. Paleob. 43, 1–93, https://doi.org/10.5479/si.00810266.43.1 (1981).

Logan, A. A new thecideid genus and species (Brachiopoda, Recent) from the Southeast North Atlantic. J. Paleontol 62, 546–551 (1988).

Logan, A. Brachiopoda collected by CANCAP IV and VI expeditions to the South-East North Atlantic. 1980-1982. Zool. Mededelingen 62, 59–74 (1988).

Lüter, C. The first Recent species of the unusual brachiopod Kakanuiella (Thecideidae) from New Zealand deep waters. Systematics and Biodiversity 3, 105–111, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1477200004001598 (2005).

Gaillard, C. & Pajaud, D. Rioultina virdunensis (Buv.) cf. ornata (Moore) brachiopode thecideen de l’epifaune de l’Oxfordien superieur du Jura Meridional. Geobios 4, 227–242, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-6995(71)80009-8 (1971).

Taylor, P. D. & Palmer, T. J. Submarine caves in a Jurassic reef (La Rochelle, France) and the evolution of cave biotas. Naturwissenschaften 81, 357–360, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01136225 (1994).

Lukeneder, A. & Harzhauser, M. Olcostephanus guebhardi as cryptic habitat for an early Cretaceous coelobite community (Valanginian, Northern Calcareous Alps, Austria). Cretaceous Res. 24, 477–485, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0195-6671(03)00066-1 (2003).

Palmer, T. J. & Fürsich, F. T. The ecology of a Middle Jurassic hardground and crevice fauna. Palaeontology 17, 507–524 (1974).

Fürsich, F. T. & Palmer, T. J. Open crustacean burrows associated with hardgrounds in the Jurassic of the Cotswolds, England. P. Geol. Assoc. 86, 171–181, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7878(75)80099-X (1975).

Wilson, M. A. Succession in a Jurassic marine cavity community and the evolution of cryptic marine faunas. Geology 26, 379–381, https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(1998)026%3C0379:SIAJMC%3E2.3.CO;2 (1998).

Wilson, M. A. & Taylor, P. D. Palaeoecology of hard substrate faunas from the Cretaceous Qahlah Formation of the Oman Mountains. Palaeontology 44, 21–41 (2001).

Taylor, P. D. & Wilson, M. A. Palaeoecology and evolution of marine hard substrate communities. Earth-Sci. Rev. 64, 1–103, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-8252(02)00131-9 (2003).

Radwańska, U. & Radwański, A. Organic communities and their habitats. in Jurassic of Poland and adjacent Slovakian Carpathians; Field trip guidebook of 7th International Congress on the Jurassic System, Poland, Kraków, September 6–18, 2006 (eds Wierzbowski, A. et al.), 194–198. (2006).

Palmer, T. J. & Wilson, M. A. Growth of ferruginous oncoliths in the Bajocian (Middle Jurassic) of Europe. Terra Nova 2, 142–147, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3121.1990.tb00055.x (1990).

Zatoń, M., Kremer, B., Marynowski, L., Wilson, M. A. & Krawczyński, W. Middle Jurassic (Bathonian) encrusted oncoids from the Polish Jura, southern Poland. Facies 58, 57–77, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10347-011-0273-1 (2012).

Wilson, M. A. Coelobites and spatial refuges in a Lower Cretaceous cobble-dwelling hardground fauna. Palaeontology 29, 691–703 (1986).

Rudwick, M. J. S. The feeding mechanism and affinities of the Triassic brachiopods Thecospira Zugmayer and Bactrynium Emmrich. Palaeontology 11, 329–360 (1968).

Michalík, J. Two representatives of Strophomenida (Brachiopoda) in the uppermost Triassic of the West Carpathians. Geol. Zborník. Geol. Carpathica 27, 79–96 (1976).

Benigni, C. & Ferliga, C. Carnian Thecospiridae (Brachiopoda) from San Cassiano Formation (Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy). Riv. Ital. Paleontol. S. 94, 515–560 (1988).

Hoel, O. A. Cementing strophomenide brachiopods from the Silurian of Gotland (Sweden): morphology and life habits. Geobios 40, 589–608, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geobios.2006.08.003 (2007).

Cooper, P. Davidsonia and Rugodavidsonia (new genus), cryptic Devonian atrypid brachiopods from Europe and South China. J. Paleontol. 70, 588–602, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022336000023556 (1996).

Baker, P. G. The classification, origin and phylogeny of thecideidine brachiopods. Palaeontology 33, 175–191 (1990).

Cartes, J. E. & Abelló, P. Comparative feeding habits of polychelid lobsters in the Western Mediterranean deep-sea communities. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 84, 139–150, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps084139 (1992).

Follesa, M. C., Cabiddu, S., Gaston, I. A. & Cau, A. On the reproductive biology of the deep-sea lobster, Polycheles typhlops (Decapoda, Palinura, Polychelidae), from the Central-Western Mediterranean. Crustaceana 80(7), 839–846 (2007).

Bengtson, S. Teasing fossils out of shales with cameras and computers. Palaeontol. Electron. 3(Art. 4), 1–14 (2000).

Haug, C. et al. Imaging and documentating gammarideans. Int. J. Zool. 2011, 380829, 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/380829 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This scientific collaboration was made possible following the 6th Symposium on Mesozoic and Cenozoic Decapod Crustaceans (June 2016, Normandy, France). We acknowledge Jean-Michel Pacaud (MNHN) for providing the access to the material as well as Sylvain Pont (MNHN) for attending us at environmental SEM imaging. JTH was kindly funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) under Ha 6300/3-1 and is currently supported by the Volkswagen Foundation with a Lichtenberg Professorship. JL acknowledges the Izaak Walton Killam Memorial Scholarship (Canada) and a Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Postdoctoral Fellowship. DA research was supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation, Yunnan Province Postdoctoral Science Foundation, NSFC grant 41861134032, and Yunnan Provincial Research Grants 2018FA025 and 2018IA073. We are very grateful to our two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments which improved the quality of the present article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.A. initiated the study, provided the initial data, and studied traces of ommatidia and provided contextual background on crustacean eyes. N.R. studied the epibionts and provided the contextual background on epibioses. J.L. studied the traces of ommatidia and provided the contextual background on crustacean eyes. M.K. identified the epibionts and provided palaeoecological background on thecideoid brachiopods. C.J. provided background on the La Voulte palaeoenvironment and the interpretation of the presence of V. parvulus in La Voulte. J.T.H. & C.H. provided background on developmental heterochrony and crustacean eyes. S.C. provided the background on the La Voulte Lagerstätte palaeoenvironment and geological context.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Audo, D., Robin, N., Luque, J. et al. Palaeoecology of Voulteryon parvulus (Eucrustacea, Polychelida) from the Middle Jurassic of La Voulte-sur-Rhône Fossil-Lagerstätte (France). Sci Rep 9, 5332 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41834-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41834-6

This article is cited by

-

Fossil evidence for vampire squid inhabiting oxygen-depleted ocean zones since at least the Oligocene

Communications Biology (2021)

-

A new polychelidan lobster preserved with its eggs in a 165 Ma nodule

Scientific Reports (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.