Abstract

The aim of this population-based, longitudinal study was to assess the association between nausea and vomiting in pregnancy (NVP) and perinatal depressive symptoms. Pregnant women (N = 4239) undergoing routine ultrasound at gestational week (GW) 17 self-reported on NVP and were divided into those without nausea (G0), early (≤17 GW) nausea without medication (G1), early nausea with medication (G2), and prolonged (>17 GW) nausea (G3). The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale at GW 17 and 32 (cut-off ≥13) and at six weeks postpartum (cut-off ≥12) was used to assess depressive symptoms. Main outcome measures were depressive symptoms at GW 32 and at six weeks postpartum. NVP was experienced by 80.7%. The unadjusted logistic regression showed a positive association between all three nausea groups and depressive symptoms at all time-points. After adjustment, significant associations with postpartum depressive symptoms remained for G3, compared to G0 (aOR = 1.66; 95% CI 1.1–2.52). After excluding women with history of depression, only the G3 group was at higher odds for postpartum depressive symptoms (aOR = 2.26; 95% CI 1.04–4.92). In conclusion, women with prolonged nausea have increased risk of depressive symptoms at six weeks postpartum, regardless of history of depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy (NVP) has for a long time fascinated the scientific community for two main reasons: its high prevalence, which has rendered it into one of the symptoms of early pregnancy and its great symptom variability, from early physiological nausea of pregnancy to a more severe condition, which may result even in maternal death at its worst form1. NVP affects 50–90% of pregnant women2,3,4. Symptoms begin early in the first trimester, peak at around nine gestational weeks (GW) and typically cease at GW 204. In 0.3–2.3% of cases it progresses to the more severe condition hyperemesis gravidarum (HG)4,5 and in 5–22% of affected women the symptoms persist throughout pregnancy4,6,7,8. WHO defines HG as NVP starting before 22 GW but the duration of symptoms and the time-point of symptom ceasing are not noted9. The vast majority of published studies focus on HG, the most severe form of NVP requiring hospitalisation and/or parenteral nutrition. However, Chandra et al. showed in the Mother Risk Program in Toronto a discordance between physical symptoms and perception of severity among women with NVP10. Moreover, less is known about the prolonged form of NVP extending in the second and third trimester of pregnancy.

Previous studies have investigated a possible association between NVP and perinatal depressive symptoms11,12. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Mitchell-Jones et al., that found increased rates of antenatal depression (AND) in women with HG, points out several methodological flaws, such as heterogeneity of the studies, small sample size, inconsistent definitions of HG, a variety of different and not validated scales for depression assessment, and the lack of adjusting for confounding factors. As a result, only one of 12 studies included in the meta-analysis had low risk of bias13.

Although the association between NVP and depression has been extensively studied, the literature from large, population-based studies considering the various spectrum of the disease is scarce. Moreover, few studies have taken into account the history of psychiatric disorders12 and their results are inconsistent11,12,14,15. A recent large population-based study on the risk of emotional distress during and after pregnancy, including 92 947 pregnant women, showed that women with HG, defined as prolonged NVP requiring hospitalization before the 25th gestational week, were more likely to report emotional distress during pregnancy and at six months postpartum, but not at 18 months postpartum compared to women without HG16. Similarly, a large population-based cohort study using Danish registers (N = 392 458) that included only women with HG and without psychiatric history, demonstrated that HG was associated with almost three times increased risk for first time onset postpartum depression (PPD) within one year after delivery17. On the other hand, a review of 38 studies without severe forms of HG, explored the impact of nausea on quality of life and demonstrated that nausea was more debilitating than vomiting, recommending caregivers to pay attention even to nausea as a single symptom18. Hence, more studies focusing on the association between perinatal depression and various types of NVP, in terms of disease onset and cessation of symptoms, are needed.

The aim of this study was to longitudinally investigate a possible association between different types of NVP within the broad disease spectrum, based on cessation of NVP symptoms and the use of medication, and perinatal depressive symptoms, taking into account the role of previous depression and adjusting for known confounding factors.

Methods

This study is part of an ongoing longitudinal cohort study of affective disorders during pregnancy and the postpartum period, the BASIC-study (Biology, Affection, Stress, Imaging and Cognition)19,20. The BASIC-study is conducted at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Uppsala University Hospital, which is a tertiary referral centre responsible for all pregnant women within the county as well as for high-risk pregnancies from nearby counties, including around 4300 deliveries a year. The study has been approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala and all participants provided written informed consent.

All pregnant Swedish-speaking women of at least 18 years of age, who were scheduled for routine ultrasound (around GW 17) between January 2010 and September 2016, were invited to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria were (1) women whose personal data were kept confidential, and (2) women with pathologic pregnancies as diagnosed by the routine ultrasound. In the BASIC project, the participation rate is approximately 22%21.

Study subjects were invited to fill-out several web-based questionnaires to assess the main exposure of the study (NVP), the main outcome (self-reported depressive symptoms) as well as several background characteristics. The first survey was answered at enrolment at GW 17 and follow-ups were answered at GW 32 and at postpartum week six. Self-reported experience of nausea in current pregnancy was assessed by three questions at GW 17: “Have you experienced any nausea during this pregnancy?” (Yes or no), “At which gestational week did the nausea cease?” (Text answer), and “Did you receive any medication against nausea in pregnancy?” (Yes or no). Questions on NVP referred to pregnancy-related nausea. No additional question on NVP symptoms was included in the questionnaire at GW 32. A small number of women were recruited before undergoing an elective cesarean delivery, around gestational week 38–39, and filled out the question on nausea at that time-point. Moreover, a few women sent in the questionnaire a few weeks later (the vast majority of them within two weeks after GW 17) and reported at that time-point information about the gestational week at which nausea symptoms ceased. Women were divided into four groups based on their answers: those who did not experience any nausea (controls; group 0, G0); those who experienced nausea ≤17 GW but did not take any medication (early nausea without medication, G1); those who experienced nausea ≤17 GW and used medication (early nausea with medication, G2); and those who experienced nausea >17 GW, regardless of the use of medication (prolonged nausea, G3).

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)22 was administered at all three time points. EPDS is an internationally used screening tool to identify depressive symptoms in the perinatal period. The EPDS consists of ten questions regarding symptoms of depressed mood across the past seven days and items are answered on a four-point scale yielding total scores between 0–30. For the present study, the cut-off used in order to classify participants by depression status, marking clinically significant depressive symptoms, was set at ≥13 points in pregnancy23 and ≥12 points postpartum24, according to previous Swedish validation studies.

Information was also gathered through questionnaires and medical records concerning sociodemographic and pregnancy variables: age at partus, body-mass index (BMI), education, employment, comorbidities (migraine, hypertension, diabetes, metabolic disease, allergy, irritable bowel syndrome, alcohol/drug addiction, chronic pain or other disease), history of depression (previous depression or contact with psychiatrist), sleeping habits before pregnancy, domestic violence in present or previous relationship, alcohol consumption, smoking before pregnancy and currently, parity, planned pregnancy, pregnancy complications (vaginal bleeding, contractions, symphysiolysis, gestational diabetes, metabolic disease, hypertension, preeclampsia or other condition (gestational week 32) and fear of delivery.

Out of the 5429 women who accepted the study invitation, 4329 (79.7%) provided full follow-up answers and were included in the current study. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Details of Ethics Approval

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala (reg. no. 2009/171) and was conducted according to the standards of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Statistical analysis

The main exposure of the study was NVP and the outcome was depressive symptoms at GW 32 and at six weeks postpartum. Bivariate associations were examined between the main exposure, the outcome, and sociodemographic and pregnancy data. Possible confounders were chosen based on significant associations in the bivariate analyses and previous literature. Covariates associated with both nausea status and depressive symptoms, at p < 0.2525, were included in multivariable logistic regression models. In models with depressive symptoms at GW 32 and postpartum week six as the outcome, the EPDS score at GW 17 was also inserted in the models to control for a possible state effect of depressive symptoms on nausea symptoms and vice versa. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Women who did not experience any NVP served as controls (G0) for the three NVP groups mentioned above. As a sensitivity analysis, the same multivariable models were run after excluding women with previous depression. Statistical significance was set at a p-value of <0.05.

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 21.0, was used for the analyses.

Baseline study characteristics

Of the total cohort, 3493 (80.7%) women experienced NVP. Two thousand six hundred and thirteen (74.8%) women with NVP up to GW 17 did not require medication against it (G1), while 395 (11.3%) women used medication (G2) and 485 (13.9%) women experienced NVP beyond GW 17 (G3). Of these 485 women, 161 (33.2%) used medication. Median gestational week at which NVP symptoms ceased in G3 group was GW 19, compared with GW 13 in G1 and GW 14 in G2, respectively. Four thousand three hundred and twenty-nine women filled in the EPDS questionnaire at GW 17, 3998 at GW 32, and 3677 women returned a completed EPDS questionnaire at six weeks postpartum. The prevalence of self-reported depressive symptoms was 8.8% (379/4329) at GW 17, 9.3% (371/3998) at GW 32 and 12.3% (452/3677) at six weeks postpartum.

Table 1 presents various background characteristics in relation to nausea groups. The majority of the study sample had age at partus between 29–35 years (56.3%). A normal BMI was found in 70% of women. Previous depression or prior contact with psychiatrist was reported by 54.6% of women and 47.5% of the total sample were primiparas. Women from the G1 group had higher education and were more often multiparas, while those from the G2 group were younger, less educated, and reported more frequently comorbidities, previous depression, domestic violence, pregnancy complications and fear of delivery. Concurrent diseases, previous depression, sleep more than eight hours before pregnancy, pregnancy complications, fear of delivery, and multiparity were significantly higher among study subjects with prolonged nausea (G3).

Associations between NVP groups and perinatal depressive symptoms

The unadjusted binary logistic regression model showed a positive association with depressive symptoms in all three NVP groups, compared to G0, at GW 17 and 32 and at six weeks postpartum. However, after adjustment for possible confounders, significant associations with postpartum depressive symptoms remained only for G3, compared to G0 (adjusted OR = 1.66; 95% CI 1.1–2.52) (Table 2).

Similarly, after excluding women with history of depression, only participants with prolonged nausea (G3) were at higher odds for depressive symptoms at six weeks postpartum (adjusted OR = 2.26; 95% CI 1.04–4.92) (Table 3).

Previous depression was independently associated with depressive symptoms at GW 17 and 32 as well as at postpartum week six.

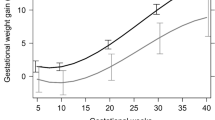

Figures 1 and 2 present unadjusted and adjusted ORs and 95% CI for depressive symptoms in different NVP groups, in the total sample as well as in participants with and without previous depression. In women with previous depression, G2 group was significantly associated with postpartum depressive symptoms, while the association between prolonged nausea (G3) and depressive symptoms was not significant (p = 0.086) (Fig. 2). However, an interaction term between previous depression and NVP groups was created and inserted in the regression models for the total sample. Since the association between this term and depressive symptoms was not significant during pregnancy and postpartum, the stratified results in Figs 1 and 2 should be interpreted with caution.

Unadjusted Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals for depressive symptoms in gestational week (GW) 17, 32 and postpartum week 6 (PPW), in relation to subgroups of nausea and vomiting during pregnancy, in the total sample and women without previous depression and with previous depression. G1: early nausea without medication; G2: early nausea with medication; G3: prolonged nausea; p < 0.05.

Adjusted Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals for depressive symptoms in gestational week (GW) 17, 32 and postpartum week 6 (PPW), in relation to subgroups of nausea and vomiting during pregnancy, in the total sample and women without previous depression and with previous depression. G1: early nausea without medication; G2: early nausea with medication; G3: prolonged nausea; p < 0.05.

Figure 3 shows the prevalence of depressive symptoms among the three previously mentioned sub-populations. As expected, a higher proportion of women with previous depression reported depressive symptoms at all three time-points during pregnancy and postpartum, compared to the total sample and to the women without previous depression (Fig. 3).

Discussion

The main finding of this study was a positive association between prolonged NVP and self-reported depressive symptoms at six weeks postpartum. Even after the exclusion of women with previous depression, this association remained significant.

Several studies have only focused on hyperemesis gravidarum13,16,25,26,27, whereas others have studied nausea and/or vomiting in general11,12,28,29,30,31,32. Consistently with other studies, we found that most pregnant women experienced NVP2,3,4 and about 75% of them belonged to the group G1 (early nausea without medication).

The definition of prolonged nausea is inconsistent, with GW 15 to 20 stated most often as the time point when nausea/HG should diminish2,33,34. In the present study, GW 17 was chosen as a discriminating point between early and prolonged nausea, a time-point similar to most other studies. Rates of prolonged nausea vary between 10–45%4,6,12,35,36. The prevalence of prolonged nausea in the current study agrees well with the rate of 14.5% reported by Colodro-Conde et al.8. Moreover, the use of medication against nausea is in good accordance with previous studies12,37. Additionally, the prevalence of depressive symptoms in our population is in line with previous studies in high–income countries, reporting figures between 7–30%38.

In the present study, a large proportion of women had history of depression or prior contact with psychiatrist (54.6%), a figure higher than in other studies12,16. These differences probably can be explained by different methods of assessing and reporting previous depression, as well as a degree of self-selection bias, with women with previous history being more prone to participate in a study focusing on depression. However, it probably did not have an impact on the results. The prevalence of self-reported depressive symptoms during pregnancy in our cohort was 8.8% and 9.3% at GW17 and 32 respectively, which are lower figures compared with a national Swedish sample (13.7–15.7%)39. At six weeks postpartum, the figure of 12.3% in the BASIC study is also well comparable with 11.1% prevalence of depressive symptoms two months postpartum in the same sample39.

Our findings of an independent association between previous depression and perinatal depressive symptoms confirm the role of previous depression as a strong risk factor for AND and PPD, a finding consistent with previous studies38,40.

In a study by Bozzo et al., no association was observed between depressive symptoms and nausea, in women without previous depression11, a finding contradicting our results that point out NVP as an independent risk factor of PPD even in previously non-depressed women. However, this study only included 57 women and could lack sufficient power. A case-control study on 78 cases and 82 controls by Aksoy et al. reported an increased frequency of depressive disorders during pregnancy in women with HG and without history of depression14. However, the authors of this study assessed severe hyperemesis with a loss of at least 5% of body weight, the study sample was rather small and they used Beck Depression Inventory for measurement of severity of depression, which might be an inappropriate instrument for NVP patients as highlighted by Fejzo et al.27. In another study, patients with severe HG in the first trimester, but without prior psychiatric disease, not only presented a negative psychiatric status during pregnancy at the time of HG symptoms, but also had higher risk of PPD15. Our results for prolonged nausea are also in line with the study by Meltzer-Brody et al. that found an association between severe NVP and PPD17. As opposed to the study by Kjeldgaard et al.14, the present study did not show significant associations between NVP and depression during pregnancy. However, our study population was not restricted to women with HG, since this study intended to examine the whole NVP spectrum and not only women with hyperemesis gravidarum.

The pathophysiology of NVP is multifactorial41,42. The dilemma whether NVP and HG are independent diseases is not yet resolved. Twin and family studies provide evidence for strong genetic predisposition in NVP8,43,44, which may account for at least 50% of symptom variation, according to the NVP Genetics Consortium8,43.

An altered intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis has been suggested in the pathophysiology of mood disorders45 and genetic analysis of subjects with severe HG has also revealed an association with intracellular calcium release channel RYR2 (Ryanodine Receptor 2) involved in vomiting46. It can be hypothesized that prolonged nausea probably has a different aetiology, compared with early types of NVP47. It is therefore possible that prolonged NVP may also have a stronger association to perinatal mood disorders. In fact, different trajectory patterns of perinatal depressive symptoms may be indicative of underlying differences in aetiology. Our results support the hypothesis about the heterogeneous pattern of NVP and depressive symptoms during pregnancy and postpartum, considering that our findings regarded only prolonged nausea and were observed regardless of the occurrence of previous depression in the study population. The observed increase of depressive symptoms at six weeks postpartum (Fig. 2) may be explained by a more abrupt hormonal decrease occurring after placental expulsion48,49, in combination with an altered immune response. Mullin et al. hypothesized that prolonged nausea might be of autoimmune origin47. In the present cohort, the women from G3 group reported more frequently comorbidities, including allergy, diabetes and irritable bowel syndrome. It could be speculated that the observed increase of depressive symptoms at six weeks postpartum might reflect these hormonal changes in an altered immunologic environment. Although the association between G3 and postpartum depressive symptoms was not significant, among women with previous depression, this finding still points to the same direction as the rest of our results for women without previous depression and the total sample.

Future research should focus on elucidating different conditions within the spectrum of NVP, with emphasis on the time of onset and ceasing of disease symptoms as well as on the duration of clinical symptoms. In this context, prolonged NVP regardless of severity of symptoms is a particularly interesting condition for further study.

The sample size, the prospective, longitudinal, population-based design and the availability of a large number of background variables can be considered as strengths of this study. Moreover, a validated instrument for the assessment of depression during pregnancy and postpartum period has been used, which can be considered as a study strength since only a few studies have focused on the association between nausea in pregnancy and perinatal depression using validated instruments so far50. Considering the heterogeneity of NVP and the relatively scarce literature on the prolonged form of NVP, this study has attempted to contribute to the understanding of this condition by focusing on different clinically relevant subtypes of the disease. The main limitation of the present study is the lack of a validated instrument for assessing severity of nausea in pregnancy, such as the PUQE score51. The women’s medical records were not assessed for information about hospitalization for HG and the frequency of vomiting episodes was not known. The present study focused instead on possible associations between different subtypes of NVP, based on the gestational week at which symptoms diminished, the use of medication, and the occurrence of perinatal depressive symptoms. Nevertheless, previous studies have shown that the women’s own perception of nausea severity was not dependent on the severity of physical symptoms10,18. As shown in the NVP Genetics Consortium twin study, the genetic correlation between duration and severity of NVP was almost perfect8. In the present study, the reported time-point when nausea symptoms ceased was used as a discriminatory factor between early and prolonged NVP, regardless of the severity of symptoms. No data on symptom onset was available, however it can be hypothesized that in the vast majority of women symptoms had already appeared after the first few gestational weeks. This limitation may be at the same time a strength of the study, since it included all women with nausea regardless of severity of clinical symptoms.

The mother study of the present project – the BASIC study – has a relatively low participation rate, which may raise questions about the representability of the cohort. Compared with pregnant women in the study area at the time, participants in the BASIC study had higher education and were more likely to have been born within Scandinavia. However, since women with lower socioeconomic status have a higher risk of depression as well as NVP52, an association seems plausible even among non-participants. Even though women with previous depression may have been oversampled because of the recruitment information about the study objective, a corresponding selection bias for NVP is unlikely since the information did not single out NVP among the risk factors of study. Still, the study should preferably be replicated among foreign-born women in Sweden, since some earlier reports indicate different rates of NVP depending on ethnicity52.

In conclusion, women with prolonged NVP beyond GW 17 have higher odds for self-reported depressive symptoms at six weeks postpartum, a finding observed even among women without previous depression. Prolonged nausea may have a different pathophysiologic background. Women experiencing prolonged nausea need proper support from health care professionals to reduce the risk of developing PPD.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Knight M. K. S., Blocklehurst P., Neilson J., Shakespeare J. & Kurinczuk J. J. (Eds) on behalf of MBRRACE-UK. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care-Lessons to inform future maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2009–12. Oxford National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford (2014).

Gadsby, R., Barnie-Adshead, A. M. & Jagger, C. A prospective study of nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. The British journal of general practice: the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners 43, 245–248 (1993).

Jarvis, S. & Nelson-Piercy, C. Management of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 342, d3606, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d3606 (2011).

Einarson, T. R., Piwko, C. & Koren, G. Quantifying the global rates of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: a meta analysis. Journal of population therapeutics and clinical pharmacology=Journal de la therapeutique des populations et de la pharamcologie clinique 20, e171–183 (2013).

Munch, S., Korst, L. M., Hernandez, G. D., Romero, R. & Goodwin, T. M. Health-related quality of life in women with nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: the importance of psychosocial context. Journal of perinatology: official journal of the California Perinatal Association 31, 10–20, https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2010.54 (2011).

Hasler, W. L., Soudah, H. C., Dulai, G. & Owyang, C. Mediation of hyperglycemia-evoked gastric slow-wave dysrhythmias by endogenous prostaglandins. Gastroenterology 108, 727–736 (1995).

Ismail, S. K. & Kenny, L. Review on hyperemesis gravidarum. Best practice & research. Clinical gastroenterology 21, 755–769, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpg.2007.05.008 (2007).

Colodro-Conde, L. et al. Nausea and Vomiting During Pregnancy is Highly Heritable. Behavior genetics 46, 481–491, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-016-9781-7 (2016).

World Health Organization. Pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium (O00–O99), Other maternal disorders predominantly related to pregnancy (O20–O29). (World Health Organization, 2004).

Chandra, K. M., Magee, L. M. & Koren, G. M. Discordance between physical symptoms versus perception of severity by women with nausea and vomiting in pregnancy (NVP). BMC pregnancy and childbirth 2, 5 (2002).

Bozzo, P., Einarson, T. R., Koren, G. & Einarson, A. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP) and depression: cause or effect? Clinical and investigative medicine. Medecine clinique et experimentale 34, E245 (2011).

Kramer, J., Bowen, A., Stewart, N. & Muhajarine, N. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: prevalence, severity and relation to psychosocial health. MCN. The American journal of maternal child nursing 38, 21–27, https://doi.org/10.1097/NMC.0b013e3182748489 (2013).

Mitchell-Jones, N. et al. Psychological morbidity associated with hyperemesis gravidarum: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 124, 20–30, https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14180 (2017).

Aksoy, H. et al. Depression levels in patients with hyperemesis gravidarum: a prospective case-control study. SpringerPlus 4, 34, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-015-0820-2 (2015).

Senturk, M. B., Yildiz, G., Yildiz, P., Yorguner, N. & Cakmak, Y. The relationship between hyperemesis gravidarum and maternal psychiatric well-being during and after pregnancy: controlled study. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine: the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstet 30, 1314–1319, https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2016.1212331 (2017).

Kjeldgaard, H. K., Eberhard-Gran, M., Benth, J. S. & Vikanes, A. V. Hyperemesis gravidarum and the risk of emotional distress during and after pregnancy. Archives of women’s mental health 20, 747–756, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-017-0770-5 (2017).

Meltzer-Brody, S. et al. Obstetrical, pregnancy and socio-economic predictors for new-onset severe postpartum psychiatric disorders in primiparous women. Psychological medicine 47, 1427–1441, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291716003020 (2017).

Wood, H., McKellar, L. V. & Lightbody, M. Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: ‘blooming or bloomin’ awful? A review of the literature. Women and birth: journal of the Australian College of Midwives 26, 100–104, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2012.10.001 (2013).

Axfors, C., Sylven, S., Ramklint, M. & Skalkidou, A. Adult attachment’s unique contribution in the prediction of postpartum depressive symptoms, beyond personality traits. Journal of affective disorders 222, 177–184, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.005 (2017).

Iliadis, S. I. et al. Prenatal and Postpartum Evening Salivary Cortisol Levels in Association with Peripartum Depressive Symptoms. PloS one 10, e0135471, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135471 (2015).

Iliadis, S. I. et al. Associations between a polymorphism in the hydroxysteroid (11-beta) dehydrogenase 1 gene, neuroticism and postpartum depression. Journal of affective disorders 207, 141–147, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.09.030 (2017).

Cox, J. L., Holden, J. M. & Sagovsky, R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science 150, 782–786 (1987).

Rubertsson, C., Borjesson, K., Berglund, A., Josefsson, A. & Sydsjo, G. The Swedish validation of Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) during pregnancy. Nordic journal of psychiatry 65, 414–418, https://doi.org/10.3109/08039488.2011.590606 (2011).

Wickberg, B. & Hwang, C. P. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: validation on a Swedish community sample. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica 94, 181–184 (1996).

Fiaschi, L., Nelson-Piercy, C. & Tata, L. J. Hospital admission for hyperemesis gravidarum: a nationwide study of occurrence, reoccurrence and risk factors among 8.2 million pregnancies. Human reproduction (Oxford, England) 31, 1675–1684, https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dew128 (2016).

London, V., Grube, S., Sherer, D. M. & Abulafia, O. Hyperemesis Gravidarum: A Review of Recent Literature. Pharmacology 100, 161–171, https://doi.org/10.1159/000477853 (2017).

Fejzo, M. S. Measures of depression and anxiety in women with hyperemesis gravidarum are flawed. Evidence-based nursing 20, 78–79, https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2017-102686 (2017).

Bustos, M., Venkataramanan, R. & Caritis, S. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy - What’s new? Autonomic neuroscience: basic & clinical 202, 62–72, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2016.05.002 (2017).

King, T. L. & Murphy, P. A. Evidence-based approaches to managing nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Journal of midwifery & women’s health 54, 430–444, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmwh.2009.08.005 (2009).

Heitmann, K., Nordeng, H., Havnen, G. C., Solheimsnes, A. & Holst, L. The burden of nausea and vomiting during pregnancy: severe impacts on quality of life, daily life functioning and willingness to become pregnant again - results from a cross-sectional study. BMC pregnancy and childbirth 17, 75 (2017).

Heitmann, K., Svendsen, H. C., Sporsheim, I. H. & Holst, L. Nausea in pregnancy: attitudes among pregnant women and general practitioners on treatment and pregnancy care. Scand J Prim Health Care 34, 13–20 (2016).

Grooten, I. J. et al. Helicobacter pylori infection: a predictor of vomiting severity in pregnancy and adverse birth outcome. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 216, 512 e511–512 e519 (2017).

McCarthy, F. P. et al. A prospective cohort study investigating associations between hyperemesis gravidarum and cognitive, behavioural and emotional well-being in pregnancy. PloS one 6, e27678, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0027678 (2011).

Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. The management of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy and hyperemesis gravidarum, Green Top Guideline No. 69. (2016).

Gavin, N. I. et al. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstetrics and gynecology 106, 1071–1083, https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db (2005).

Fejzo, M. S. et al. Symptoms and pregnancy outcomes associated with extreme weight loss among women with hyperemesis gravidarum. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 18, 1981–1987 (2009).

Poursharif, B. et al. The psychosocial burden of hyperemesis gravidarum. Journal of perinatology: official journal of the California Perinatal Association 28, 176–181, https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jp.7211906 (2008).

Biaggi, A., Conroy, S., Pawlby, S. & Pariante, C. M. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. Journal of affective disorders 191, 62–77, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.014 (2016).

Rubertsson, C., Wickberg, B., Gustavsson, P. & Radestad, I. Depressive symptoms in early pregnancy, two months and one year postpartum-prevalence and psychosocial risk factors in a national Swedish sample. Arch Womens Ment Health 8, 97–104, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-005-0078-8 (2005).

Robertson, E., Grace, S., Wallington, T. & Stewart, D. E. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: a synthesis of recent literature. General hospital psychiatry 26, 289–295, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.02.006 (2004).

Sherman, P. W. & Flaxman, S. M. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy in an evolutionary perspective. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 186, S190–197 (2002).

Goodwin, T. M. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: an obstetric syndrome. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 186, S184–189 (2002).

Colodro-Conde, L. et al. Cohort Profile: Nausea and vomiting during pregnancy genetics consortium (NVP Genetics Consortium). Int J Epidemiol 46, e17, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyv360 (2017).

Zhang, Y. et al. Familial aggregation of hyperemesis gravidarum. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 204, 230 e231–237 (2011).

Maluquer, S. S., Arranz, B. & San, L. Depression improvement with calcium heparin. General hospital psychiatry 24, 450–451 (2002).

Fejzo, M. S. et al. Genetic analysis of hyperemesis gravidarum reveals association with intracellular calcium release channel (RYR2). Molecular and cellular endocrinology 439, 308–316, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2016.09.017 (2017).

Mullin, P. M. et al. Risk factors, treatments, and outcomes associated with prolonged hyperemesis gravidarum. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine: the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstet 25, 632–636 (2012).

Iliadis, S. I. et al. Personality and risk for postpartum depressive symptoms. Archives of women’s mental health 18, 539–546, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-014-0478-8 (2015).

Skalkidou, A., Hellgren, C., Comasco, E., Sylven, S. & Sundstrom Poromaa, I. Biological aspects of postpartum depression. Women’s health (London, England) 8, 659–672, https://doi.org/10.2217/whe.12.55 (2012).

Ezberci, I., Guven, E. S., Ustuner, I., Sahin, F. K. & Hocaoglu, C. Disability and psychiatric symptoms in hyperemesis gravidarum patients. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics 289, 55–60, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-013-2934-5 (2014).

Koren, G. et al. Validation studies of the Pregnancy Unique-Quantification of Emesis (PUQE) scores. Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology: the journal of the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 25, 241–244, https://doi.org/10.1080/01443610500060651 (2005).

Lacasse, A., Rey, E., Ferreira, E., Morin, C. & Berard, A. Epidemiology of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: prevalence, severity, determinants, and the importance of race/ethnicity. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 9, 26 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We would like to sincerely thank all the women participating in the BASIC study as well as Charlotte Hellgren, Emma Bränn, Hanna Henriksson and Marianne Kördel, for their creative thinking, hard work and dedication in the organization and management of this project. This study was supported by the Swedish Research Council (grant number: 521-2010-3293), the Council for Working Life and Social Research (grant number: 2007-1955), the Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation (grant number: MMW2011.0115), the Swedish Medical Association (grant number: SLS-250581) and the Uppsala University Hospital (grant number: 2012-Skalkidou). The funders did not influence the study design, execution, manuscript, or publishing process.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.I. has contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data and has drafted and revised the article for important intellectual content. C.A. has contributed to analysis of data and has drafted and revised the article for important intellectual content. S.J. has contributed to acquisition of data and has revised the article for important intellectual content. A.S. has contributed to the conception and design of the study, to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data and has revised the article for important intellectual content. A.M.L. has contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data and has drafted and revised the article for important intellectual content. All authors have approved the final version of the article to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Iliadis, S.I., Axfors, C., Johansson, S. et al. Women with prolonged nausea in pregnancy have increased risk for depressive symptoms postpartum. Sci Rep 8, 15796 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-33197-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-33197-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Effect of nausea and vomiting during pregnancy on mother-to-infant bonding and the mediation effect of postpartum depression: the Japan Environment and Children’s Study

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2023)

-

Self-reported vomiting during pregnancy in North-east Nigeria: perceptions, prevalence, severity and impacts

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2022)

-

A longitudinal investigation of the influence of psychological factors on nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy

Archives of Women's Mental Health (2022)

-

Mode of conception in relation to nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: a nested matched cohort study in Sweden

Scientific Reports (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.