Abstract

Porphyrin-based molecules play an important role in natural biological systems such as photosynthetic antennae and haemoglobin. Recent organic chemistry provides artificial porphyrin-based molecules having unique electronic and optical properties, which leads to wide applications in material science. Here, we successfully produced many macroscopically anisotropic structures consisting of porphyrin dimers by light-induced solvothermal assembly with smooth evaporation in a confined volatile organic solvent. Light-induced fluid flow around a bubble on a gold nanofilm generated a sub-millimetre radial assembly of the tens-micrometre-sized petal-like structures. The optical properties of the petal-like structures depend on the relative angle between their growth direction and light polarisation, as confirmed by UV-visible extinction and the Raman scattering spectroscopy analyses, being dramatically different from those of structures obtained by natural drying. Thus, our findings pave the way to the production of structures and polycrystals with unique characteristics from various organic molecules.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Natural photosynthetic systems found in plants and bacteria convert solar energy into chemical energy with 100% quantum efficiency, using nanoscale petal-like antennae comprising porphyrin-based molecules (PBMs) to harvest photons of various wavelengths1,2. Another example is represented by a PBM-Fe2+ complex found in haemoglobin, which is responsible for the delivery of oxygen by animal blood cells3,4. The unique properties of PBMs have been utilised in molecular electronics components5,6,7, gas sensors8,9, dye-sensitised solar cells10,11, and contrast agents for bio-imaging12,13, with recent advances in organic chemistry enabling syntheses of various types of porphyrin dimers, polymers, or conjugated tapes with controllable length featuring strong infrared absorption, two-photon absorption, and unique electronic properties7,14,15. Importantly, structurally planar porphyrins can be used to construct diversely shaped nanoscale self-assembled structures such as nanoparticles, nanosheets, and nanorods16,17,18,19,20, with morphology control playing a vital role in the development of novel porphyrin-based materials.

Remote control of molecular assembly by external field–induced modulation of the growth environment would allow the production of unconventional structures with an extended application range. For example, light-induced forces arising from electromagnetic interaction between light and matter were used to selectively assemble an artificial light-harvesting structure using metallic nanorods extracted from diversely shaped nanoparticles under resonant laser illumination21, and also applied to amino acid crystallisation and sulfathiazole nucleation at the air-liquid interface22,23. Another approach to assemblies of nano- and micron-sized objects (e.g., nanoparticles, soft oxometalates, carbon nanotubes, metallic nanoparticles, and bacteria) is based on light-induced fluid flow originating from thermofluid dynamics under heating by laser light (i.e., photothermal assembly (PTA))24,25,26,27,28,29. Although the above reports on PTA utilised aqueous solutions with low evaporation rates, the use of volatile organic solvents is expected to achieve faster light-induced fluid flow due to their high evaporation rate.

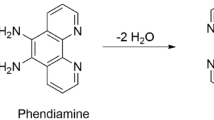

Here, being inspired by natural PBM-containing functional structures, we produced PBM-based structures as unconventional optical materials by utilising a high-temperature and high-evaporation-rate solvothermal process in an organic solvent under PTA conditions, since such processes are often used to prepare highly crystalline inorganic structures30,31. A porphyrin dimer (meso-meso, β-β, β-β triply linked ZnII-diporphyrin32,33 exhibiting exquisite crystallinity due to its planar molecular framework) was utilised as the model PBM. A toluene solution of diporphyrin was placed on a gold nanofilm and the solution/nanofilm interface was vertically illuminated with an infrared continuous wave (CW) laser to generate fluid flow for transporting and a bubble for the deposition of the transported molecules. Then, we investigated the optical properties and molecular arrangement of the prepared structures by utilising UV-visible and Raman scattering spectroscopy analyses.

Light-induced solvothermal assembly (LSTA) of diporphyrin

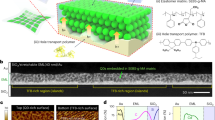

CW laser illumination on the gold nanofilm resulted in intense local heating, since the thermal conductivity of metal films decreases with their decreasing thickness34,35, inducing fluid flow and generating a sub-millimetre-sized bubble as shown in Fig. 1a (the detail of the experimental setup is in Supplementary Figure S1). The temperature of the solvent (toluene) surrounding the bubble sharply increased beyond its boiling point (111 °C), and vapourisation of the solvent afforded a supersaturated solution around the spreading bubble and subsequently produced a sub-millimetre radial assembly of many structures with petal-like shapes (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Movie S1). Notably, the bubble formation was observed already after 1-second illumination (Fig. 1b, top right), with the bright area in the centre of the above image corresponding to the region where the bubble attaches itself to the substrate, and the dark area representing the shadow of this bubble. Careful observation of the location of LSTA-produced structures in Fig. 1 shows that they are generated not at the periphery of the bubble but at the ground contact portion of the bubble and the substrate. As a hypothesis, it is considered that these structures were produced under a solvent-thermal synthesis in the diporphyrin solution slightly remaining between the bubble and the substrate under a high pressure environment due to strong pressure by bubbles and laser heating. Therefore, we call this generation method “Light-induced solvothermal assembly (LSTA)”.

Light-induced solvothermal assembly (LSTA) of diporphyrins into anisotropic structures with petal-like shapes. (a) Schematic representation of LSTA. (b) Optical transmission images reflecting the growth of anisotropic LSTA-produced structures of diporphyrins. Numbers in images correspond to illumination times.

After the CW laser illumination was turned off, the bubble separated itself from the substrate and floated away, with the petal-like structures of diporphyrins re-dissolving unless the solvent was immediately removed. Thus, to hinder the re-dissolution, the solvent was removed with a paper wiper due to the action of capillary forces, which resulted in the irreversible formation of an assembly of tens-micrometre-sized LSTA-produced structures of diporphyrins (Fig. 2a). It has been confirmed that a part of LSTA-produced structures is separated from the substrate or changes its direction during the solvent removal process. Furthermore, field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) analyses revealed that each petal-like structure has radially branched morphology and that structures obtained by natural drying of a toluene solution of the diporphyrin take differently rugby-ball-like morphology (Fig. 2b,c, respectively).

Microscopic images of diporphyrin-based structures. (a) Optical transmission images of LSTA-produced structures under non-polarised white light (halogen lamp). (b) Field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM) images of an LSTA-produced petal-like structure and (c) of structures obtained by natural drying with an inset of the corresponding optical transmission image. Optical response dependent on polarisation angle

The extinction spectra (sum of absorption and scattering) of LSTA-produced structures and natural drying-produced structures (Fig. 3a) were locally observed in the photometric area as shown in Fig. 2a, they were compared with the extinction spectrum obtained in the toluene solution of the parent diporphyrin (Supplementary Figure S2 and S3). Peaks around wavelengths = 458, 485 and 585 nm were not shifted, but it was confirmed that peaks around wavelength = 556, 641 nm (solution) were shifted to short wavelength region (blue shift) and long wavelength region (red shift) respectively (Supplementary Table S1). This peak shift may be due to the formation of J aggregates (blue shift) and H aggregates (red shift) in which molecules are aggregated in one dimension. Therefore, both J-aggregate and H-aggregate are considered to be contained in LSTA-produced structures and natural drying-produced structures (the stability of diporphyrin is high and it is reported that the structure is maintained even at high temperature of 500 K or more36, and diporphyrin degeneration by LSTA did not occur.).

Optical anisotropy of LSTA-produced structures. (a) Locally observed extinction spectra of LSTA-produced structures and natural drying-produced structures (a reference spectrum of the parent diporphyrin solution is shown in Supplementary Figure S3). Both of the extinction spectra were averaged at three different positions. (b) Extinction spectra of an LSTA-produced structure and natural drying-produced structures recorded under various polarisation conditions. (c) Optical transmission images of LSTA-produced structures recorded under various polarisation conditions of white light. The length of the scale bars is 20 µm. In the top figure, the shape of a LSTA-produced structure was approximated with a triangle, and shows the polarisation angles for lowest and highest extinction.

The radial growth pattern of LSTA-produced structures implied that growth occurred in a specific direction and could thus result in optical anisotropic properties. To test this assumption, we measured extinction spectra of the LSTA-produced structures (Fig. 3b) and observed transmission images of them (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Movie S2) under polarised light (polarisation angle (15–105°, step = 45°)) using a polarising plate). Each of the LSTA-produced structures clearly exhibited macroscopically and optically anisotropic properties. When we carefully checked the relationship between polarisation transmitted images and polarisation angles, we noticed that the morphology of the LSTA-produced structure is correlated to polarisation angle where extinction occurred most strongly in the optical transmission process. Interestingly, an LSTA-produced structure absorbed or scattered light polarised perpendicularly to the radial growth direction, being transparent to light polarised parallel to the above direction in Fig. 3c. Similar behaviour was also observed for other LSTA-produced structures, implying that these structures comprised anisotropic crystals. Conversely, a single natural drying-produced structure with rugby-ball-like shape did not exhibit pronounced anisotropic properties(Supplementary Figure S4), and showed weakly polarisation-dependent property, with this anisotropy vanishing in the averaged spectrum (Fig. 3b). These results suggest that light-induced fluid flow would transport constituent molecules around a bubble to result in a directional assembly in the case of LSTA, whereas the solution was evaporated uniformly and slowly to result in a directionless growth in the case of natural drying.

Raman scattering properties

The possible arranged structures of diporphyrin are considered to be the sequence shown in Fig. 4a (Model 1 and Model 2) and the sequence in which diporphyrin exists parallel to the substrate. The latter model can be rejected since it is unlikely that extinction spectra vary greatly with the polarisation angle of the illumination light as shown in Fig. 3b. Therefore, in order to investigate which array structure is possible in Fig. 4a, the Raman scattering intensities of molecular vibration modes (C (α) -C (meso), C (α) -C (β), C (β) -C (β), C (α) -N) are compared. The LSTA-produced structures showing different contrast (Region <i> and Region <ii> shown in Fig. 4a), were measured by Raman scattering spectroscopy to investigate the arrangement of diporphyrins in LSTA-produced structures. Here, the LSTA-produced structure of Region <ii> is considered to indicate a colour different from that of Region <i> because its orientation changed during solvent removal process. Fig. 4b shows the Raman scattering spectra of the Regions <i> and <ii> as well as that of natural drying-produced structure. Since the intensity at each peak wavenumber 1515 cm−1, 1615 cm−1 (C(α)-C(meso), C(α)-C(β), C(β)-C(β), C(α)-N) is higher in the order of Region <ii>, natural drying, and Region <i> (Supplementary Table S2), Model 2 is considered to be valid (Supplementary Table S2). On the other hand, at 1575 cm-1, the Raman intensity of Region <i> in of LSTA-produced structure showed the maximum intensity and that of natural drying-produced structure was higher than that of Region <ii>. This indicates that the π-bond at around the peak wave number of 1575 cm -1, and the assumption that there is a contribution is consistent with Model 2.These results strongly support that each LSTA-produced structure exhibited the high anisotropy, and that the molecular arrangements can be modulated by LSTA, differently from isotropic natural drying-produced structures.

Raman scattering spectra of LSTA-produced structures and natural drying- produced structures. (a) Optical transmission image of LSTA-produced structures for white light polarisation angle 165° (enlarged image of a part of Fig. 2a), and models for available arrangement of diporphyrins in Region <i> and <ii> . (b) Raman scattering spectra of Region <i> and Region <ii> in each LSTA-produced structure averaged at five different positions in both cases. Also, Raman scattering spectrum of natural drying–produced structures averaged over five different structures is shown together. Each dotted line and number indicates the peak position of 1: C(meso)-C(Ar), Ar, 2, 3, 4: C(α)-C(meso), C(α)-C(β), C(β)-C(β), C(α)-N37.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that LSTA produces macroscopically anisotropic petal-like structures of diporphyrin in an organic solvent via light-induced evaporation process, with the polarisation-dependent optical extinction of these structures being in contrast to the behaviour of natural drying-produced structures. Moreover, from the extinction spectrum and Raman spectral analysis, the following two models of diporphyrin sequence and binding were suggested: (i) an LSTA-produced structure contain both the J aggregates and H aggregates, (ii) Diporphyrin has an arrangement perpendicular to the substrate and with its planar surface oriented toward the laser illumination point. Thus, broadband anisotropic optical extinction of assembled PBMs can be used to produce micron-scale white light filters for optical interconnections comprising photonic structures, with the obtained results paving the way to laser-mediated solvothermal assembly of arbitrary nanoscale organic molecules into unconventional crystal polymorphs at the desired position on the substrate. Further measurements of electrical conductivity and other nonlinear optical responses of assembled molecules are expected to extend the applications of the above structures to nanoelectronics, nanophotonics, and next-generation bio-inspired photonic information technologies.

Methods

Synthesis of diporphyrin

The diporphyrin (porphyrin dimer) used in this work was prepared and characterised elsewhere32,33.

Experimental setup for LSTA

Supplementary Figure S1 shows schematic illustrations of the experimental setup for LSTA. The sample holder comprising a slide glass and three cover slips (with one of them covered by a gold nanofilm) with double-sided tape (0.1-mm-thick) is shown in Supplementary Figure S1. After injection of the liquid sample into the holder, it was set on the stage of an inverted microscope (Eclipse Ti-U, Nikon, Japan) equipped with a 1064-nm CW laser light source (Supplementary Figure S1). The diameter of the laser spot was set to 1.0 μm by using a 100 × objective (Numerical Aperture = 1.3), with the power of laser light penetrating the cover slip measured by a power meter (UP17P-6S-H5 with tuner, Gentec Electro-Optics, Canada) and used throughout the experiments. The ~10-nm-thick (as measured by a profilometer (Dektak150, Takaoshin, Japan)) gold nanofilm was deposited on a cover slip as a light-absorbing layer by sputtering (E-1010, Hitachi, Japan).

After the sample holder was placed onto the stage of the inverted microscope, a diporphyrin solution in toluene (1.0 mg of diporphyrin powder was dispersed in 10 mL of toluene) was placed on the gold nanofilm and illuminated by CW laser light at an intensity of ~1.3 × 107 W/cm2 for 3 min. During illumination, the deposition process was monitored using a cooled charge-coupled device camera (DS-Filc-L3, Nikon, Japan) under bright-field conditions. When laser illumination was turned off, the solvent was immediately removed by the capillary force of a sheet of KIMWIPES (Kimberly Clark Corp., USA).

Microscopic observations and optical measurements

Double-sided tape was removed from the cover slip coated by the gold nanofilm to allow FE-SEM imaging (SU8010, Hitachi High-Tech., Japan) of the LSTA-produced structures. The optical extinction spectra of LSTA-produced structures were locally observed within a 10-μm-diameter photometric area by UV-visible spectrometry (USB-4000; Ocean Optics, USA), and Raman scattering spectra were acquired using a laser Raman microscope (Raman-11, Nanophoton, Japan) using 532 nm laser with y-polarisation. Polarisation spectroscopy was performed by incorporating a polariser (SIGMA KOKI, Japan) into the illumination system. The extinction spectrum and the Raman spectrum were analyzed using the commercial soft ware (Origin, OriginLab Corporation, USA). The natural drying–produced structures obtained after approximately 10 min. by naturally evaporating a toluene solution of the diporphyrin at room temperature (25 °C) on a substrate (gold nanofilm on a cover slip) (referred as “natural drying” in the main text) were also characterised using the same equipment.

References

Bahatyrova, S. et al. The native architecture of a photosynthetic membrane. Nature 430, 1058–1062 (2004).

Scheuring, S. & Sturgis, J. N. Chromatic adaptation of photosynthetic membranes. Science 309, 484–487 (2005).

Paoli, M., Marles-Wright, J. & Smith, A. Structure–function relationships in heme-proteins. DNA Cell Biol. 21, 271–280 (2002).

Poulos, T. L. Heme enzyme structure and function. Chem. Rev. 114, 3919–3962 (2014).

Jurow, M., Schuckman, A. E., Batteas, J. D. & Drain, C. M. Porphyrins as molecular electronic components of functional devices. Coord. Chem. Rev. 254, 2297–2310 (2010).

Mohnani, S. & Bonifazi, D. Supramolecular architectures of porphyrins on surfaces: The structural evolution from 1D to 2D to 3D to devices. Coord. Chem. Rev. 254, 2342–2362 (2010).

Tanaka, T. & Osuka, A. Conjugated porphyrin arrays: synthesis, properties and applications for functional materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 943–969 (2015).

Rakow, N. A. & Suslick, K. S. A colorimetric sensor array for odour visualization. Nature 406, 710–713 (2000).

Sivalingam, Y. et al. Gas-sensitive photoconductivity of porphyrin-functionalized ZnO nanorods. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 9151–9157 (2012).

Wang, C.-L. et al. Enveloping porphyrins for efficient dye-sensitized solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 6933–6940 (2012).

Mathew, S. et al. Dye-sensitized solar cells with 13% efficiency achieved through the molecular engineering of porphyrin sensitizers. Nat. Chem. 6, 242–247 (2014).

Ethirajan, M., Chen, Y., Joshi, P. & Pandey, R. K. The role of porphyrin chemistry in tumor imaging and photodynamic therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 340–362 (2011).

Hayashi, K. et al. Near-infrared fluorescent silica/porphyrin hybrid nanorings for in vivo cancer imaging. Adv. Funct. Mater. 22, 3539–3546 (2012).

Tsuda, A. & Osuka, A. Fully conjugated porphyrin tapes with electronic absorption bands that reach into infrared. Science 293, 79–82 (2001).

Aratani, N., Kim, D. & Osuka, A. π-Conjugation enlargement toward the creation of multi-porphyrinic systems with large two-photon absorption properties. Chem. - Asian J. 4, 1172–1182 (2009).

Nikiforov, M. P. et al. The effect of molecular orientation on the potential of porphyrin−metal contacts. Nano Lett. 8, 110–113 (2008).

Sandanayaka, A. S. D., Araki, Y., Wada, T. & Hasobe, T. Structural and photophysical properties of self-assembled porphyrin nanoassemblies organized by ethylene glycol derivatives. J. Phys. Chem. C 112, 19209–19216 (2008).

Visser, J., Katsonis, N., Vicario, J. & Feringa, B. L. Two-dimensional molecular patterning by surface-enhanced Zn-porphyrin coordination. Langmuir 25, 5980–5985 (2009).

Medforth, C. J. et al. Self-assembled porphyrin nanostructures. Chem. Commun. 7261–7277 (2009).

Dong, R. et al. Self-assembly and optical properties of a porphyrin-based amphiphile. Nanoscale 6, 4544–4550 (2014).

Ito, S. et al. Selective optical assembly of highly uniform nanoparticles by doughnut-shaped beams. Sci. Rep. 3(3047), 1–7 (2013).

Sugiyama, T., Adachi, T. & Masuhara, H. Crystallization of glycine by photon pressure of a focused CW laser beam. Chem. Lett. 36, 1480–1481 (2007).

Li, W. et al. Non-photochemical laser-induced nucleation of sulfathiazole in a water/ethanol mixture. Cryst. Growth Des. 16, 2514–2526 (2016).

Fujii, S. et al. Fabrication and placement of a ring structure of nanoparticles by a laser-induced micronanobubble on a gold surface. Langmuir 27, 8605–8610 (2011).

Roy, B. et al. Self-assembly of mesoscopic materials to form controlled and continuous patterns by thermo-optically manipulated laser induced microbubbles. Langmuir 29, 14733–14742 (2013).

Nishimura, Y. et al. Control of submillimeter phase transition by collective photothermal effect. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 18799–18804 (2014).

Yamamoto, Y., Shimizu, E., Nishimura, Y., Iida, T. & Tokonami, S. Development of a rapid bacterial counting method based on photothermal assembling. Opt. Mater. Express 6, 1280–1285 (2016).

Iida, T. et al. Submillimetre network formation by light-induced hybridization of zeptomole-levelDNA. Sci. Rep. 6(37768), 1–9 (2016).

Robert, H. M. L. et al. Light-assisted solvothermal chemistry using plasmonic nanoparticles. ACS Omega 1, 2–8 (2016).

Cundy, C. S. & Cox, P. A. The Hydrothermal Synthesis of Zeolites: History and Development from the Earliest Days to the Present Time. Chemical Reviews 103, 663–702 (2003).

Raccuglia, P. et al. Machine-learning-assisted materials discovery using failed experiments. Nature 533, 73–76 (2016).

Kamo, M. et al. Metal-dependent regioselective oxidative coupling of 5,10,15-triarylporphyrins with DDQ-Sc(OTf)3 and formation of an oxo-quinoidal porphyrin. Org. Lett. 5, 2079–2082 (2003).

Tanaka, T., Nakamura, Y. & Osuka, A. Bay-area selective thermal [4 + 2] and [4 + 4] cycloaddition reactions of triply linked ZnII diporphyrin with o-xylylene. Chem. - Eur. J. 14, 204–211 (2008).

Zhang, Q. G., Cao, B. Y., Zhang, X., Fujii, M. & Takahashi, K. Influence of grain boundary scattering on the electrical and thermal conductivities of polycrystalline gold nanofilms. Phys. Rev. B 74(134109), 1–5 (2006).

Feng, B., Li, Z. & Zhang, X. Prediction of size effect on thermal conductivity of nanoscale metallic films. Thin Solid Films 517, 2803–2807 (2009).

Wiengarten, A. et al. Surface-assisted Dehydrogenative Homocoupling of Porphine Molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 9346–9354 (2014).

Kim, D. & Osuka, A. Photophysica Properties of Directly Linked Linear Porphyrin Arrays. J. Phys. Chem. A 107, 8791–8816 (2003).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Prof. K. Imura, Prof. S. Ito, and Prof. C. Kojima for fruitful experiment-related discussions, and Dr. M. Tamura for his support. T.I. and H.Y. acknowledge JST ACT-C Grant No. JPMJCR12ZE. This work was partially supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (No. JP15H03010, No. JP26286029), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) (No. JP17H00856), Grant-in-Aid for Exploratory Research (No. JP15K14697), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas “Nano-Material Manipulation and Structural Order Control with Optical Forces” (No. JP16H06507) and “Science of Atomic Layers” (No. JP25107002) funded by JSPS. T.I. and S.T. acknowledge the Canon Foundation and the Key Project Grant Program of Osaka Prefecture University, whereas Y.Y., Y.N. and N.F. acknowledge JSPS Fellowship for Young Scientists (No. JP18J13307, No. JP15J09975 and No. JP15J01145), and H.Y. acknowledges the Kansai Research Foundation for Technology Promotion and Asahi Glass Foundation for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.I., H.Y., and S.T. initiated the described research and equally contributed to its design. Y.Y., N.Y., T.I., and S.T. performed the photothermal porphyrin dimer assembly. N.F., T.T., and H.Y. prepared the above porphyrin dimer. Y.Y., T.I., H.Y., A.O., and S.T. prepared the figures and the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript, contributed to this work equally.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamamoto, Y., Nishimura, Y., Tokonami, S. et al. Macroscopically Anisotropic Structures Produced by Light-induced Solvothermal Assembly of Porphyrin Dimers. Sci Rep 8, 11108 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-28311-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-28311-2

This article is cited by

-

Damage-free light-induced assembly of intestinal bacteria with a bubble-mimetic substrate

Communications Biology (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.