Abstract

Ferroelectric materials are fascinating for their non-volatile switchable electric polarizations induced by the spontaneous inversion-symmetry breaking. However, in all of the conventional ferroelectric compounds, at least two constituent ions are required to support the polarization switching1,2. Here, we report the observation of a single-element ferroelectric state in a black phosphorus-like bismuth layer3, in which the ordered charge transfer and the regular atom distortion between sublattices happen simultaneously. Instead of a homogenous orbital configuration that ordinarily occurs in elementary substances, we found the Bi atoms in a black phosphorous-like Bi monolayer maintain a weak and anisotropic sp orbital hybridization, giving rise to the inversion-symmetry-broken buckled structure accompanied with charge redistribution in the unit cell. As a result, the in-plane electric polarization emerges in the Bi monolayer. Using the in-plane electric field produced by scanning probe microscopy, ferroelectric switching is further visualized experimentally. Owing to the conjugative locking between the charge transfer and atom displacement, we also observe the anomalous electric potential profile at the 180° tail-to-tail domain wall induced by competition between the electronic structure and electric polarization. This emergent single-element ferroelectricity broadens the mechanism of ferroelectrics and may enrich the applications of ferroelectronics in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Ferroelectrics are well known for their applications in the non-volatile memories4 and electric sensors5, and their applications have been extended to the areas of ferroelectric photovoltaics for the efficient renewable energy harvesting6 and synaptic devices for the powerful neuromorphic computing7. Recently, research on ferroelectrics has been expanded to the two-dimensional (2D) limits with distinct performance8,9,10, including perovskite ferroelectrics at the unit-cell thickness11,12, single layer ferroelectrics with in-plane or out-of-plane polarization13,14 and 2D moiré ferroelectrics by the van der Waals stacking15,16.

Normally, ferroelectric materials are compounds that consist of two or more different constituent elements1,2. The electron redistribution during the chemical bond formation instantaneously renormalizes the valence orbitals and yields the anion and cation centres. Further relative distortion, sliding or charge transfer between the positive and negative charge centres in a unit cell produces the ordering of electric dipoles to sustain the ferroelectricity17,18,19. By contrast, as the atoms in a unit cell of an elementary substance are identical, ordered electric dipole or even ferroelectric polarization seem difficult to form spontaneously. The realization of single-element ferroelectricity also lacks experimental demonstration so far. Nevertheless, elements situated between metals and insulators in the periodic table show flexible bonding abilities to adopt several states in one system, such as Sn atoms in the 2D Sn2Bi honeycomb structure show binary states20,21. Even in elemental boron, ionicity with inter-sublattice charge transfer was found to arise from the different bonding configurations in each sublattice (B12 and B2)22. The subtle balance between metallic and insulating states in these elements is easy to shift by the different sublattice environments so that both states may be realized simultaneously in a unit cell, providing possibilities to produce cations and anions in a unit cell to achieve ferroelectricity in single-element materials. Recently, some theoretical works have been devoted to exploring single-element polarity or ferroelectricity in elemental Si (ref. 23), P (ref. 24,25), As (ref. 25), Sb (ref. 25,26), Te (ref. 27) and Bi (ref. 25,26). In particular, Xiao et al. predicted that the family of group-V single-element materials in a 2D van der Waals form28, that is, the monolayer As, Sb and Bi in the anisotropic α-phase structure, have a non-centrosymmetric ground state to support both cations and anions in a unit cell and produce in-plane ferroelectric polarization along the armchair direction.

Spontaneous symmetry breaking in single BP-Bi layer

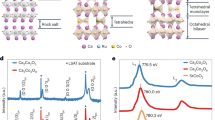

The monolayer α-phase Bi has a lattice structure similar to black phosphorous3,29, and will be referred to black phosphorous-like-Bi (BP-Bi) thereafter. Owing to the ultra-large atomic number, Bi has a weak hybridization between the 6s and 6p orbitals so that it features partial sp2 character other than the homogenous tetrahedral sp3 configuration that exists in the black phosphorus26,28. This brings in a small buckling (Δh) between the neighbouring sublattices with the loss of centrosymmetry30,31. As shown in Fig. 1a, the breaking of inversion symmetry allows BP-Bi to adopt two domain states, either the Δh = d0 or Δh = −d0 state. Our first-principles calculations reveal the two states can be switched to each other by crossing a small energy barrier of 43 meV per unit cell (Fig. 1b). Moreover, the buckling degree of freedom enlarges the band gap and lifts the degeneracy of the pz orbitals at sublattice A and B (Extended Data Fig. 1). Taking Δh = d0 for instance (Fig. 1c, Δh adopts the right minimum of the double-well potential), the valence band and conduction band at the Γ point are mainly contributed by the pz orbitals of A and B sublattice, respectively. When the Fermi level crosses the band gap, the valence pz orbitals at the A sublattice are fully occupied, and the pz orbitals at the B lattice are empty. In real space, this corresponds to electron transfer from sublattice B to sublattice A, leading to a spontaneously polarized character (Fig. 1d). The anharmonic double-well potential with a small barrier implies the possible ferroelectric switch between the two domain states. The nearly linear dependence between the polarization (P) and the buckling degree (Δh), along with the mirror (glide) symmetry refer to the (01) surface (in-plane central surface) (Fig. 1a), indicate that Δh is an order parameter to characterize the ferroelectricity of BP-Bi.

a, Schematic lattice structure of single layer BP-Bi. Top and side views of Δh = d0 state are shown in the top and middle panels, respectively. For the Δh = −d0 state, only a side-view model is shown in the bottom panel. The topmost Bi atoms are coloured light blue to only guide the eye for a better comparison with AFM images. b, Calculated free energy per unit cell (u.c.) and polarization P versus the buckling Δh show an anharmonic double-well potential and nearly linear relation, respectively. c, Band structure of BP-Bi when Δh adopts the right minimum (d0) of the double-well potential in b. The size of the red (blue) circles represents the contributions of the pz orbital of sublattice A(B). d, Illustration of the revolution of pz orbitals at sublattice A and B (top panel). Projected pz valence charge density corresponding to three buckling conditions (Δh = −d0, Δh = 0, Δh = d0) are shown in the bottom panel. e, STM image of BP-Bi on HOPG (V = 0.2 V, I = 10 pA). Scale bar, 10 nm. f,g, AFM images of two domains (D1 (f) and D2 (g)). Ball-and-stick models of the top two layers are superimposed to highlight the atom position. h, dI/dV measured at the domain area and a domain wall (head-to-head, V = 0.7 V, I = 1.2 nA). The density-of-states (DOS) maximum corresponding to the pz bands at Γ point is labelled as Ei and Eii. i, Δf(z) spectra measured on the two sublatticed in f and g. A0 and B0 are up-shifted by 2 Hz for clarity. Vertical short bars mark the turn points of the Δf(z) curves. Tip height z = −260 pm (f,g,i) relative to the height determined by the setpoint V = 100 mV, I = 10 pA above the BP-Bi surface.

Experimentally, we grew BP-Bi on highly oriented pyrolytic graphite (HOPG). Figure 1e shows a scanning tunnelling microscopy (STM) image of the monolayer BP-Bi with some second layer nanoribbons along the \([0\bar{1}]\) direction (Extended Data Fig. 2a)32. The atomic-resolved non-contact atomic force microscopy (AFM) measurement indicates two different states in two neighbouring domains separated by a domain wall (Fig. 1f,g and Extended Data Figs. 3f–o and 8). We performed force spectroscopy measurements (the Δf(z) spectra) to find out the relative distance between the Bi atoms and tip apex33. At the constant-height mode, the measured height difference of the turning points of the Δf(z) spectra on sublattice A and B in Fig. 1i quantitatively present the buckling degree, and the result Δh0 = −Δh1 = 40 pm is determined (Extended Data Fig. 5a–d). The dI/dV spectrum at the domain wall shows the pz bands (Ei and Eii) moving to a higher binding energy compared to the normal domain position, and a sharp peak occurs in the band gap (Fig. 1h), which will be elaborated in detail later.

In-plane polarization

In the buckling structure, the charge transfer between the sublattice A and B of BP-Bi is represented by the energy splitting of the pz orbitals and the variation of the surface electrostatic potential between A and B. According to the calculated band structure in Fig. 1c, the dI/dV peak corresponding to pz orbitals should be below zero (occupied state, Ei) for one sublattice but above zero (empty state, Eii) for the other sublattice. Figure 2b shows the dI/dV cascade along the red dashed arrow (across an ABABA lattice) in Fig. 2a, revealing two traces of peaks. The valence band peak Ei is clearly strong at the A sublattice (that is, points 1, 3, 5) but weak at the B sublattice (points 2, 4), whereas the conduction band peak Eii shows the opposite behaviour. At the 2D scale, the dI/dV mapping of the valence band (Fig. 2c) and conduction band (Fig. 2d) show the same feature: filled pz orbitals localize at the A sublattice, while the empty pz orbitals localize at the B sublattice, confirming the predicted electron transfer from B to A.

a, AFM image of a monolayer BP-Bi. Red and blue dotted circles highlight two atoms in the two sublattices. Scale bar, 4.0 Å. b, Constant-height dI/dV spectra obtained along the red dashed arrow in a. c,d, Constant-height dI/dV mapping of the occupied states (c) and empty states (d) in the same area as a. e, Typical frequency shift (Δf) curve as a function of sample bias is measured above the Bi atoms at the constant-height mode (black circles). Red parabolic fitting (red solid line) yields the V* at the maximum to represent the LCPD. The inset shows the uniform fitted residual. f, AFM image of the normal BP-Bi contains four topmost A atoms and one B atom in the middle. g, LCPD grid map (30 × 30) measured at the area of f illustrates the localized potential difference between the A and B sublattices. h, Simulated electrostatic potential above the same structure at a distance of 3 Å from the top Bi plane. Dotted circles in g and h mark the position of A and B atoms. Tip heights z = −260 pm (a), −100 pm (b), −150 pm (c,d), −230 pm (f) and −100 pm (e,g), relative to the height determined by the setpoint V = 100 mV, I = 10 pA above the BP-Bi surface.

Another piece of evidence to prove electron transfer is the disparity in the local contact potential difference (LCPD) on each sublattice at atomic scale34,35. Figure 2e presents a typical Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM) measurement implemented by recording the frequency shift as a function of the sample bias voltage. The electrostatic force caused by the contact potential difference (CPD) between the sample and tip changes by sweeping the bias voltage. When the CPD is totally compensated by the bias (VCPD = V*), the electrostatic force reaches the minimum, corresponding to the parabolic apex in the frequency shift curve in Fig. 2e. By recording the bias voltage V* site by site in a lateral grid, the surface potential is mapped out and shown in Fig. 2g. AFM was performed simultaneously to determine the atomic structure at the same area (Fig. 2f). It is obvious that the two sublattices A and B have different surface potentials. Using the spontaneous buckled model (Fig. 1a), we calculated the electrostatic potential shown in Fig. 2h, which reproduces the experimental LCPD map and indicates the electron enrichment at the topmost A sublattice. Ultimately, on the basis of the above dI/dV and LCPD measurement combined with the in-plane distorted atom structure, the in-plane polarization can be confirmed.

Ferroelectric switching

The polarization of a ferroelectric material can be reversed by an applied electric field36. In our experiments, we use the in-plane component of electric field from the conductive STM/AFM tip to switch the polarization of small ferroelectric domains close to the tip37. To facilitate the switching, we set the tip near a domain wall so that the size of the switched domain is comparable to the limited range of the electric field produced by the tip end (Fig. 3a). During the sample bias sweeping at a specific tip height, the IV spectra are recorded as shown in Fig. 3d. When the voltage ramps from negative to positive bias, a low conductance appears at around 0.2 V due to the band gap of BP-Bi under the tip (blue series curves). Continuous bias increase causes a small current jump labelled by the red vertical bars. While sweeping the voltage back (from positive to negative), a larger hysteretic current is maintained with a substantial conductance emerging at around 0.2 V in the gap (red series curves). According to the dI/dV curves of the domain wall (Fig. 1h), the large in-gap current indicates the domain wall has been moved to the tip position during the application of the positive bias. When the bias voltage reaches a negative value VSW, the current jumps to the original level, suggesting the domain wall is moved back. The AFM images (Fig. 3b,c) after the forwards and backwards voltage sweeping demonstrate the movement of the domain wall directly. Figure 3c shows the domain wall movement to the left side with a distance of four lattice periods after the forwards manipulation, and Fig. 3b shows the domain wall moving back to the original position after changing the bias backwards to below VSW. Accordingly, the ferroelectric switching between the two domain states (Δh = d0 and Δh = −d0) is experimentally verified. The domain wall in Fig. 3a can be assigned to the 180° head-to-head ferroelectric domain wall with the polarization labelled in Fig. 3b,c.

a, AFM image of a 180° head-to-head domain wall of monolayer BP-Bi. Scale bar, 20 Å. b,c, AFM images of the same area marked by the red rectangle in a, show the reversal switching before (b) and after (c) the manipulation. Scale bars, 6.0 Å. The red dots mark the location of tip during switching. The side-view models are put in the upper panels of (a–c). d, Series of IV curves with the sample bias sweeping at different tip-sample distances (from Δz = 0 to 60 pm). The inset schematically shows how the polarization of BP-Bi changes with electric field. Red vertical bars mark the switching voltage at the positive bias side. e, Tip-height dependent switching voltage (VSW) and measured CPD (VCPD). Error bars represent the standard deviation from several measurements. f, Schematic diagram of the electric field produced by the STM/AFM tip. g, Calculated electric potential and in-plane electric field on the BP-Bi surface. Tip height z = −260 pm (a), −250 pm (b,c) and the initial tip height (Δz = 0 pm) in d,e is −50 pm relative to the height determined by the setpoint V = 100 mV, I = 10 pA above the BP-Bi surface.

In the hysteretic domain manipulation, the switching voltage at both positive bias side (VSW0) and negative bias side (VSW) show tip-height dependence. When the relative tip height Δz rises from 0 to 60 pm, the switching voltage VSW0 at the positive bias side is found to increase while VSW at the negative bias decreases (Fig. 3d,e). We also measured the LCPD at different heights (VCPD) (Fig. 3e), which reveals a gradual LCPD decrease with the tip height (Δz) climb due to the semimetallicity of graphite38. The tip in our setup is grounded with a bias voltage (VS) applied to the sample, the electric potential of the HOPG can be written as ΦS = VS − VCPD. Thus, the increase of tip height strengthens the electric field under the tip through the decrease of the VCPD, but weakens the electric field by the rise of the tip-sample distance. Nonetheless, because ΦS is small at the negative bias side and large at the positive bias side, we find the electric field is dominated by the LCPD at the negative bias side (VSW), and dominated by the tip-sample distance at the positive bias side (Extended Data Fig. 7g,h). Therefore, the switching bias required to trigger the same domain switch at a higher tip height has to decrease at the negative bias side but increasing at the positive bias side accordingly, which also explains the correlated variation between VSW and VCPD in Fig. 3e.

Quantitatively, the electric potential and electric field below the tip are derived by solving the Poisson equation in prolate spheroidal coordinates. The switch bias at the positive bias side was set to VS = 1.0 V (approximately ΦS = 1.6 eV). The calculated results are shown in Fig. 3g. Differentiating the electric potential on the BP-Bi surface (Φ) produces an in-plane electric field of as large as −20 mV Å−1 at the distance of roughly 10 Å to the centre (r = 0 Å). On the other hand, we can estimate the coercive field by \({E}_{{\rm{c}}}=2\sqrt{-{\alpha }^{3}/27\beta }\), where α = −8.93 × 10−18 F−1 and β = 4.25 × 10−39 m2 C−2 F−1 are the coefficients of the second- and fourth-order terms in the Landau model fitted to the density functional theory- (DFT-) derived double-well potential in Fig. 1b (ref. 36). The estimated Ec = 15.7 mV Å−1 is comparable to the calculated in-plane electric field above (Fig. 3g). This may be understood that the highly localized in-plane electric field works mainly on the domain part between tip and wall, thus demanding that the electric field overcomes Ec. It is noticeable that they are also close to that in the reported ferroelectric polymer PVDF39 and strained transition metal oxides40,41. As spontaneous polarization (Ps) is determined by the same α and β through \({P}_{{\rm{s}}}=\sqrt{-\alpha /\beta }\), the consistency between Ec and in-plane electric field E in our experiment also verifies the DFT result Ps = 0.41 × 10−10 C per m (Fig. 1b), which resembles the polarization of monolayer SnTe (roughly 1 × 10−10 C per m)42.

180° domain walls

Besides the 180° head-to-head domain wall in the monolayer BP-Bi (Figs. 1e, 3a, 4a and Extended Data Fig. 9), we also observe the conjugated 180° tail-to-tail domain wall (Fig. 4c). The AFM measurements show that the 180° head-to-head domain wall has a wall width of about 15 Å (three unit cells, shadow area in Fig. 4e), whereas the 180° tail-to-tail domain wall has a wider width of roughly 56 Å (12 unit cells, shadow area in Fig. 4g). The dI/dV measurements of the head-to-head domain wall reveal a one-dimensional electronic state in the band gap, and both conduction band and valence band near the wall bend to a higher binding energy (Fig. 4b), indicating the accumulation of electrons around the wall. A close determination of the band bending by extracting Ei peak and measuring the LCPD by KPFM show the same bending profile and a total band bending of about 170 meV (Fig. 4f). When turning to the tail-to-tail domain wall, the dI/dV spectra, however, show the incongruous band movement in the valence band and conduction band (Fig. 4d). The same band bending assessment methods by the Ei analysis and LCPD measurement in Fig. 4h suggest a smaller but identical bending direction to the head-to-head domain wall (Fig. 4f).

a,c, AFM images of the 180° head-to-head domain wall (a) and tail-to-tail domain wall (c) with the side-view models in respective upper panels. Scale bars, 20 Å. b,d, dI/dV line maps perpendicularly cross the domain walls along the red dashed arrows in a and c show the band evolution of the head-to-head (b) and tail-to-tail (d) domain wall. e,g, Experimental buckling degree of Bi atoms around the head-to-head domain wall (e) and tail-to-tail domain wall (g). f,h, Band bending of the head-to-head domain wall (f) and tail-to-tail domain wall (h) measured by tracing the Ei peak in the dI/dV line maps (black dots), and LCPD measurement (red dots). i–l, The calculated order parameter (i,k) and electric profile (j,l) of the head-to-head (i,j) and tail-to-tail (k,l) domain wall with (w, red) or without (w/o, blue) considering the screened Coulomb interaction (SC) on the basis of the thermodynamic theory. The red solid curves in (k,l) are the calculated results containing the buckling-dependent work function variation (WF) in the tail-to-tail domain wall. The shadow areas in e, g, i and k highlight the width of respective domain walls. Wall width is defined by |Δh| < d0 × tanh(1). Tip heights z = −250 pm (a), −50 pm (b,f), −260 pm (c), −60 pm (d,h) and −290 pm (e,g), relative to the height determined by the setpoint V = 100 mV, I = 10 pA above the normal BP-Bi surface.

To understand the experimental observation above, we calculate the order parameter profile at the domain wall using the Landau–Ginzburg–Devonshire theory43,44. Considering the intrinsic p-type doping (Extended Data Fig. 4), the screened Coulomb interaction is included to take into account the screening effect of charge carriers on the ferroelectric instability45. Figure 4i–l shows the calculated wall width and surface potential profile in the 180° head-to-head and tail-to-tail domain walls. It is apparent that there is nearly no difference between the cases with or without the screened Coulomb interaction in the head-to-head domain wall (Fig. 4i,j). The wall width is about three unit cells and the surface potential increase exponentially at the domain wall, consistent with the experimental observations (Fig. 4e,f). However, for the tail-to-tail domain wall, the wall width and the surface potential have totally different behaviours regarding the cases with and without a screened Coulomb interaction (Fig. 4k,l). For the case without a screened Coulomb interaction, the tail-to-tail domain wall has a similar narrow width (three unit cells) as the head-to-head domain wall. Involving the screened Coulomb interaction results in a wall width four times larger (12 unit cells), which matches the experimental observations.

As demonstrated, BP-Bi is heavily p-type doped (Extended Data Fig. 4). The upwards band bending at the tail-to-tail domain wall in principle will increase the local carrier concentration drastically, which accordingly decrease the Thomas–Fermi screening length and strongly screen the Coulomb interaction or depress the spontaneous polarization Ps (refs. 46,47). Generally, the wall width can be simplified as \({D}_{{\rm{W}}}=4\sqrt{k/2{P}_{{\rm{s}}}^{2}\beta }\) (k is the gradient coefficient)36, thus the rise of charge carrier density at the domain wall broadens the wall width and flattens the surface potential at tail-to-tail domain wall (red dashed lines in Fig. 4k,l). By contrast, the band bending at the head-to-head domain wall makes the Fermi level shift to the middle of the band gap and lessens the carrier density, which consequently narrows the wall width (Fig. 4i). However, as the screening length at low carrier density is notably larger than the efficient range of the Coulomb interaction45, the screening effect changes little with the continued reduction of the carrier concentration, resulting in a slight width shrinking at the head-to-head domain wall.

In addition, the evolution of the electronic structure correlated to the atomic buckling (Δh) at the tail-to-tail domain wall is discussed. Early theoretical and experimental research showed that the band structure is highly buckling dependent30,48. Our refined DFT calculations suggest that the position of the Fermi level decreases monotonously with the buckling reduction (Extended Data Fig. 1c), which implies an increase in the work function or gradual charge transfer between the substrate and BP-Bi layer at the wide tail-to-tail domain wall. With this consideration, the amended calculation of the surface potential reverses at the tail-to-tail domain wall, and acts as a similar band bending as that of the head-to-head domain wall (red solid curve in Fig. 4l). This result reproduces the electric potential measurements (Fig. 4h) and illustrates the conjugative correlations between electronic structure and ferroelectric distortion in this monolayer BP-Bi system.

Conclusion

In this work, we experimentally confirmed in-plane polarization and observed ferroelectric switching in a single-element BP-Bi monolayer, demonstrating the capability to realize ferroelectric polarization in an elementary substance or single-element compound22 (for example, bismuth bismuthide here). The spontaneous charge redistribution and the ferroelectric atomic distortion in the BP-Bi show the intercorrelation between the electronic structure and inversion symmetry. Owing to the heavily p-type doping of BP-Bi, the screened Coulomb interaction from the carrier density and the electronic modulation by the ferroelectric distortion were observed at the 180° tail-to-tail domain wall. The single-element ferroelectricity inspires the advantages of ferroelectrics to electrically modulate the band structure, as well as other potential emergent phenomena such as topology and superconductivity beyond magnetism19.

Methods

Sample preparation and characterization

Single layer BP-Bi was prepared in an ultra-high vacuum molecular-beam epitaxy chamber that connected to the Omicron LT-STM system (1 × 10−10 mbar). HOPG was first cleaved in air and then immediately loaded into the molecular-beam epitaxy chamber to degas the surface contamination. Bismuth with a purity of 99.999% was evaporated by a K-cell to the substrate that kept at room temperature. All the STM or scanning tunnelling spectroscopy (STS) and AFM/KPFM measurements were performed at 4.3 K with a tungsten tip glued to the qPlus AFM sensor, except the variable temperature experiment reached the respective temperature by the liquid nitrogen cryostat cooling and resistance counter heating. The clean and atomically sharp tip was obtained by repeat voltage pulses and controllable indentations on the Au(111) substrate. Further vertical CO molecule manipulation was carried out on the same surface to get a CO functionalized apex49. Differential conductance (dI/dV) was obtained by a lock-in technique with a 3–10-mV and 963-Hz modulation superimposed on the sample bias. The AFM sensor with a resonance frequency of 27 kHz and a quality factor of 30,000–70,000 was excited to an amplitude of 40 pm for the AFM measurement and 60 pm for the KPFM measurement. All the images have been processed and rendered using MATLAB and WSxM software50.

First-principles calculations

First-principle calculations were carried out within the DFT formalism, as implemented in the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package51. The local density approximation was used for exchange-correlation functional with a projector augmented-wave52 pseudopotentials, treating Bi 5d 6s 6p as valence electrons. The cut-off of the plane wave basis was set above 500 eV to guarantee that the absolute energies are converged to 1 meV. Grimme’s method53 was used to incorporate the effects of van der Waals interactions in all geometry optimizations. The vacuum region was set to larger than 25 Å to minimize artificial interactions between images. The 2D Brillouin zone was sampled by a Monkhorst–Pack54 k-point mesh and it is 12 × 12 for the unit cell. The positions of atoms were fully relaxed until the Hellmann–Feynman force on each atom was less than 0.01 eV Å−1. The convergence criteria for energy were set to 10−5 eV. The electronic-structure calculations were performed within the scalar relativistic approximation, including a spin-orbit coupling effect. Hybrid functional (HSE06)54 was also used to confirm the band gap. All energy levels were calibrated by the corresponding core levels.

Moiré pattern and domain wall

Owing to the twofold symmetry of the BP-Bi, the moiré patterns produced by stacking single layer BP-Bi on HOPG can be classified into two categories: in type 1, the zigzag BP-Bi (\([0\bar{1}]\) direction) aligns at a small twist angle θ with respect to the zigzag direction of graphite; in type 2, the zigzag BP-Bi aligns at a small twist angle θ with respect to the armchair direction of graphite. Among them, the ±1.7° type 2 (θ = ±1.7°) moiré pattern is unique for the homogeneous stacking sequence between BP-Bi and graphite along the short axis of the moiré superlattice (Extended Data Fig. 2e), which therefore shows the stripe contrast in the STM measurement (Extended Data Fig. 2d). In this kind of moiré pattern, the domain wall is constrained to along the stripe direction owing to the corresponding stripe-like strain and potential distribution in the moiré pattern (Extended Data Fig. 8a and the bottom-right part of Extended Data Fig. 2a). Conversely, the type 1 moiré pattern has the gradually changing stacking sequence along both periodic directions (Extended Data Fig. 2b,c), thus allows the 180° domain wall with an incline angle to exist (Extended Data Fig. 2a,f,g).

For all the domain walls, there are two critical angles that are used to describe them adequately: the angle between polarization vectors of two neighbouring domains and the smallest angle between the domain wall and the polarization vector nearby. We name the last one as the incline angle and only use this part ahead of the domain’s name when the front one is 180°. But we neglect the prefix when the incline angle is 90°, because this kind of domain wall (90° inclined 180° head-to-head or tail-to-tail domain wall) is the most frequently found (Figs. 3 and 4 and Extended Data Figs. 2a and 9). Extended Data Fig. 8 shows some uncommon domain walls in the measurement, they are charged 54° inclined 180° head-to-head domain wall (Extended Data Fig. 8a), neutral 90° head-to-tail domain wall (Extended Data Fig. 8b) and charged 90° head-to-head domain wall (Extended Data Fig. 8c).

Band edge and band gap

From the dI/dV measurement on BP-Bi domain area, it is easy to identify a band gap with the valence band maximum (VBM) near the Fermi level and the conduction band minimum (CBM) at around 0.27 eV. To determine the band structure and band edge precisely, we measured the quasiparticle interference (QPI) of the VBM and CBM at the spatial domain and energy domain (Extended Data Fig. 4). The Fourier transform of the 2D STS maps at both valence band and conduction band show the intravalley scattering characterized by the qc and qv in the centre of the reciprocal space. Fourier transform–STS along the high symmetry direction (Γ-X2) show the parabolic dispersion at both valence band and valence band near the Fermi surface. The parabolic fittings of the QPI yields the VBM and CBM to be at 26 ± 5 and 289 ± 5 meV, respectively, which confirms a band gap of roughly 260 meV and the intrinsic hole doping in the BP-Bi.

Buckling determination and edge reconstruction

Extended Data Fig. 5 shows the AFM measurement of a crater and two different zigzag edges in the BP-Bi. Although the crater is so small that the edges are very short, the reconstruction can be easily confirmed on the atomic scale. Further inspection of the long straight zigzag edges in a BP-Bi ribbon island also shows the same results. The reconstructed gaps and 4a superperiod are responsible for the missing of regular band bending at both zigzag edges (Supplementary Information)55.

The buckling (Δh) of the BP-Bi can be roughly determined by obtaining the height difference of the turning points of the Δf(z) spectra that were measured above the A and B sublattice. A more precise measurement requires the subtraction of the background force. Here we use the force spectroscopy that was obtained at the crater as the van der Waals force background (curve C). Removing this term gives a smaller buckling value (Δh = 0.38 Å) but still a different frequency shift at the turning point of the two Δf(z) spectra, which means the background force at A and B is different. This can be understood to provide the information that the nearest and next-nearest neighbours of A and B have different z coordinates and, the A and B atoms have different electrostatic charges. At the tip–sample distance in our experiment, assuming that the electrostatic charge difference is neglectable and the background force for A and B has the same form Fb(z), thereof the (subtracted) net force for atom A and B can be written as FA0(z) = FA(z) − Fb(z − Δh) and FB0(z) = FB(z) − Fb(z), respectively. Because A and B are the same Bi element, curves FA0(z) and FB0(z) should be identical by a translation of Δh along the z direction, which can be expressed as FA0(z − Δh) = FB0(z). With this consideration, we derived the net buckling Δh = 0.35 Å as shown in Extended Data Fig. 5d. Nevertheless, as the derived net buckling (Δh = 0.35 Å) is close to the raw buckling (Δh = 0.40 Å) that obtained without background-force subtraction, and the difference between them fade away when reducing the buckling to zero at the domain wall, we still use the raw buckling Δh by simply calculating the height difference of the turning points of the Δf(z) spectra to depict the wall thickness in Fig. 4.

Domain manipulation

The polarization switching at another 180° head-to-head domain wall is shown in the Extended Data Fig. 7. Similar to the one in Fig. 3, the ferroelectric hysteresis during the electric field manipulation is distinguishable by the current variation at various tip-sample distances. But we note the switching voltage (VSW) changes from wall to wall because of the localized strain and defect, which is also the reason that causes the hysteresis loop a lateral shift so that deviates from the symmetric schematic in the inset of Fig. 3d (ref. 56).

To evaluate the electric field below the tip, we did the calculation in the prolate spheroidal coordinates (η, ξ). By treating the tip surface as a hyperboloid ηt and the graphite surface as an infinite metal plane η = 0, the potential in the tunnelling gap reads:

where sample potential ΦS = VS − VCPD and

Transformation to the Cartesian coordinates (r, z) gives rise to the potential distribution Φ(r, z) and the derivative in-plane electric field E(r) at the BP-Bi plane (Fig. 3f,g).

In the meantime, the tip-height-dependent electric field at both switch sides can be calculated. As shown in Extended Data Fig. 7g,h, the electric field intensity (absolute value) below the tip decreases with the tip lifting at the positive bias side (VS = 0.7 V), but increases at the negative bias side (VS = −0.4 V). This suggests the electric field intensity is mainly dominated by the tip-sample distance elongation at the positive side, while by the decline of VCPD at the negative side, which explains the upwards shift of VSW0, VSW2 and downwards shift of VSW, VSW1 when increasing the tip-sample distance (Fig. 3d,e and Extended Data Fig. 7f).

Ferroelectric phase transition

At higher temperatures, it is challenging to perform atomic force spectroscopy to extract the ferroelectric distortion directly. But the small atomic distortion can be magnified by the moiré pattern so that it is distinguishable by the STM topographic measurement directly. Particularly, the drastic buckling reversal at the 180° head-to-head domain wall contribute to a lateral shift of the moiré superlattice. This yields a kink of the moiré lattice crossing the wall. Extended Data Fig. 9 shows the domain wall we measured at a series of different temperatures in the same area. At low temperatures, the kink produced by the 180° head-to-head domain wall is easy to find (blue line), but it smears at 165 K and disappears at 210 K. Apart from the STM topography measurement, we did the dI/dV measurement at the domain wall, and found the peak of the in-gap state also shows similar behaviour, that is, the peak weakened with the rise of the temperature and disappeared at 210 K. The gradual changes of the kink and spectra not only exclude the tip-induced domain manipulation that could move the domain wall away by the electric field, but also derive a Curie temperature of about 210 K with a possible second-order phase transition.

Calculation of the order parameter profile at the 180° head-to-head and tail-to-tail domain wall

We use a three-dimensional (3D) counterpart that contains multilayers of 180° head-to-head or tail-to-tail domain walls along the z direction to inspect the development of the domain profile. The equivalent 3D model with an adjusted interlayer distance has the merits of involving the screening effect of the substrate and simplifying the calculation to be one-dimensional. To satisfy the free energy minimization of the ferroelectrics with second-order phase transition, we have36,43,44

where x is the axis perpendicular to the domain wall plane; α, β, k have the same definitions as those in the main text and β > 0, α = α0(T − TC) with the constant α0 > 0. In the meantime, the electric potential φ and polarization P across the domain wall (along the x axis) fulfil the Poisson equation

where the ε is the permittivity, ρ is the charge density that mainly contributed by the band edges of BP-Bi. According to the density of states (DOS) features reflected by the dI/dV curve and the QPI measurement in the Extended Data Fig. 4, we approach the carrier concentration by using the parabolic band edge at the CBM and a non-parabolic mode at the VBM with the fitted parameters. At T = 4.3 K under the 2D limit, they can be approximated as

Here, \(\hbar \) is the reduced Planck’s constant, EF is the Fermi energy level, e is the absolute value of the electron charge, mC (mV) and EC (EV) is the effective-mass and the energy of the conduction (valence) band edge, respectively. The solving of the differential equations above produces the conjugated results at the head-to-head and tail-to-tail wall (blue curves in Fig. 4i–l).

When considering the Coulomb screening of the ferroelectric dipole, we calculate the Curie temperature at different screening length or charge concentration to include the screening term13,57. Thus, we rewrite the coefficient α as α0(T − TC(ρ)). From the results of the red dashed curved in Fig. 4k, substantial wall broadening can be observed because of the weakening of the spontaneous polarization near the wall. Further consideration of the Fermi energy at different buckling level (Δh) is conducted by introducing an extra carrier-concentration term ρ′(Δh), which is approximated linearly by referring to the DFT calculations (Extended Data Fig. 1c).

Data availability

The main data supporting the finding of this work are available within this paper. Extra data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding authors.

Code availability

The computer code used for numerical calculation and data processing are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Khomskii, D. I. Transition Metal Compounds (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2014).

Horiuchi, S. & Tokura, Y. Organic ferroelectrics. Nat. Mater. 7, 357–366 (2008).

Gou, J. et al. The effect of moiré superstructures on topological edge states in twisted bismuthene homojunctions. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba2773 (2020).

Scott, J. F. Applications of modern ferroelectrics. Science 315, 954–959 (2007).

Dagdeviren, C. et al. Conformable amplified lead zirconate titanate sensors with enhanced piezoelectric response for cutaneous pressure monitoring. Nat. Commun. 5, 4496 (2014).

Young, S. M. & Rappe, A. M. First principles calculation of the shift current photovoltaic effect in ferroelectrics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 116601 (2012).

Khan, A. I., Keshavarzi, A. & Datta, S. The future of ferroelectric field-effect transistor technology. Nat. Electron. 3, 588–597 (2020).

Qi, L., Ruan, S. & Zeng, Y. J. Review on recent developments in 2D ferroelectrics: theories and applications. Adv. Mater. 33, 2005098 (2021).

Wu, M. Two-dimensional van der Waals ferroelectrics: scientific and technological opportunities. ACS Nano 15, 9229–9237 (2021).

Guan, Z. et al. Recent progress in two-dimensional ferroelectric materials. Adv. Electron. Mater. 6, 1900818 (2020).

Choi, K. J. et al. Enhancement of ferroelectricity in strained BaTiO3 thin films. Science 306, 1005–1009 (2004).

Wang, H. et al. Direct observation of room-temperature out-of-plane ferroelectricity and tunneling electroresistance at the two-dimensional limit. Nat. Commun. 9, 3319 (2018).

Chang, K. et al. Discovery of robust in-plane ferroelectricity in atomic-thick SnTe. Science 353, 274–278 (2016).

Zhou, Y. et al. Out-of-plane piezoelectricity and ferroelectricity in layered α-In2Se3 nanoflakes. Nano Lett. 17, 5508–5513 (2017).

Zhang, Y., Kiper, N., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T. & Kong, J. Unconventional ferroelectricity in moiré heterostructures. Nature 588, 71–76 (2020).

Vizner Stern, M. et al. Interfacial ferroelectricity by van der Waals sliding. Science 372, 142–1466 (2021).

Stern, E. A. Character of order-disorder and displacive components in barium titanate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 037601 (2004).

Wu, M. & Li, J. Sliding ferroelectricity in 2D van der Waals materials: related physics and future opportunities. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2115703118 (2021).

Spaldin, N. A. & Ramesh, R. Advances in magnetoelectric multiferroics. Nat. Mater. 18, 203–212 (2019).

Gou, J. et al. Binary two-dimensional honeycomb lattice with strong spin-orbit coupling and electron-hole asymmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 126801 (2018).

Gou, J. et al. Realizing quinary charge states of solitary defects in two-dimensional intermetallic semiconductor. Natl Sci. Rev. 9, nwab070 (2022).

Oganov, A. R. et al. Ionic high-pressure form of elemental boron. Nature 457, 863–867 (2009).

Guo, Y., Zhang, C., Zhou, J., Wang, Q. & Jena, P. Lattice dynamic and instability in pentasilicene: a light single-element ferroelectric material with high Curie temperature. Phys. Rev. Appl. 11, 064063 (2019).

Hu, T., Wu, H., Zeng, H., Deng, K. & Kan, E. New ferroelectric phase in atomic-thick phosphorene nanoribbons: existence of in-plane electric polarization. Nano Lett. 16, 8015–8020 (2016).

Zhang, H., Deng, B., Wang, W. C. & Shi, X. Q. Parity-breaking in single-element phases: ferroelectric-like elemental polar metals. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 30, 415504 (2018).

Guo, Y., Zhu, H. & Wang, Q. Large second harmonic generation in elemental α-Sb and α-Bi monolayers. J. Phys. Chem. C 124, 5506–5513 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Two-dimensional ferroelectricity and switchable spin-textures in ultra-thin elemental Te multilayers. Mater. Horizons 5, 521–528 (2018).

Xiao, C. et al. Elemental ferroelectricity and antiferroelectricity in Group-V monolayer. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1707383 (2018).

Nagao, T. et al. Nanofilm allotrope and phase transformation of ultrathin Bi film on Si(111)−7×7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 105501 (2004).

Lu, Y. et al. Topological properties determined by atomic buckling in self-assembled ultrathin Bi(110). Nano Lett. 15, 80–87 (2015).

Jin, K. H., Oh, E., Stania, R., Liu, F. & Yeom, H. W. Enhanced Berry curvature dipole and persistent spin texture in the Bi(110) monolayer. Nano Lett. 21, 9468–9475 (2021).

Scott, S. A., Kral, M. V. & Brown, S. A. A crystallographic orientation transition and early stage growth characteristics of thin Bi films on HOPG. Surf. Sci. 587, 175–184 (2005).

Gross, L. et al. Bond-order discrimination by atomic force microscopy. Science 337, 1326–1329 (2012).

Mohn, F., Gross, L., Moll, N. & Meyer, G. Imaging the charge distribution within a single molecule. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 227–231 (2012).

Albrecht, F. et al. Probing charges on the atomic scale by means of atomic force microscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 076101 (2015).

Tagantsev, A. K., Cross, L. E. & Fousek, J. Domains in Ferroic Crystals and Thin Films (Springer, 2010).

Chang, K. et al. Microscopic manipulation of ferroelectric domains in SnSe monolayers at room temperature. Nano Lett. 20, 6590–6597 (2020).

Liscio, A., Palermo, V., Müllen, K. & Samorì, P. Tip-sample interactions in Kelvin probe force microscopy: quantitative measurement of the local surface potential. J. Phys. Chem. C 112, 17368–17377 (2008).

Ducharme, S. et al. Intrinsic ferroelectric coercive field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 175–178 (2000).

Pertsev, N. A. et al. Coercive field of ultrathin Pb(Zr0.52Ti0.48)O3 epitaxial films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 83, 3356–3358 (2003).

Jo, J. Y., Kim, Y. S., Noh, T. W., Yoon, J. G. & Song, T. K. Coercive fields in ultrathin BaTiO3 capacitors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 19–22 (2006).

Wan, W., Liu, C., Xiao, W. & Yao, Y. Promising ferroelectricity in 2D group IV tellurides: a first-principles study. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 132904 (2017).

Gureev, M. Y., Tagantsev, A. K. & Setter, N. Head-to-head and tail-to-tail 180° domain walls in an isolated ferroelectric. Phys. Rev. B 83, 184104 (2011).

Eliseev, E. A., Morozovska, A. N., Svechnikov, G. S., Gopalan, V. & Shur, V. Y. Static conductivity of charged domain walls in uniaxial ferroelectric semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B. 83, 235313 (2011).

Wang, Y., Liu, X., Burton, J. D., Jaswal, S. S. & Tsymbal, E. Y. Ferroelectric instability under screened coulomb interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 247601 (2012).

Kittel, C. Introduction to Solid State Physics (Wiley, 1996).

Kolodiazhnyi, T., Tachibana, M., Kawaji, H., Hwang, J. & Takayama-Muromachi, E. Persistence of ferroelectricity in BaTiO3 through the insulator-metal transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 147602 (2010).

Yamada, K. et al. Ultrathin bismuth film on 1 T-TaS2: structural transition and charge-density-wave proximity effect. Nano Lett. 18, 3235–3240 (2018).

Bartels, L., Meyer, G. & Rieder, K. H. Controlled vertical manipulation of single CO molecules with the scanning tunneling microscope: a route to chemical contrast. Appl. Phys. Lett. 71, 213–215 (1997).

Horcas, I. et al. WSXM: a software for scanning probe microscopy and a tool for nanotechnology. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 78, 013705 (2007).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558–561 (1993).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Klimeš, J., Bowler, D. R. & Michaelides, A. Chemical accuracy for the van der Waals density functional. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 22, 022201 (2010).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Sun, J. T. et al. Energy-gap opening in a Bi(110) nanoribbon induced by edge reconstruction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 246804 (2012).

Damodaran, A. R., Breckenfeld, E., Chen, Z., Lee, S. & Martin, L. W. Enhancement of ferroelectric Curie temperature in BaTiO3 films via strain‐induced defect dipole alignment. Adv. Mater. 26, 6341–6347 (2014).

Hallers, J. J. & Caspers, W. J. On the influence of conduction electrons on the ferroelectric Curie temperature. Phys. Status Solidi 36, 587–592 (1969).

Acknowledgements

We thank W. Chen, Y. Xu, C. Yang and J. Hu for the fruitful discussions. This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Singapore (grant no. R-144-000-405-281). L.C. acknowledges support from the National Key R&D Program of China (grant no. 2018YFE0202700), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 12134019) and the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant no. XDB30000000). Y.L. acknowledges supports from National Key R&D Program of China (grant no. 2019YFE0112000), the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. LR21A040001 and LDT23F04014F01) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 11974307). Y.-L.H. acknowledges the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (project no. 12004278). L.C. acknowledges the support from the CAS Project for Young Scientists in Basic Research (grant no. YSBR-054).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.G., L.C., Y.L. and A.T.S.W. proposed and conceived this project. J.G., Y.-L.H. and S.D. contributed to the experiment. X.Z., H.B. and Y.L. provided the theoretical support on the experiment. J.G., A.A., S.A.Y., L.C., Y.L. and A.T.S.W. did the data analysis. J.G., L.C., S.A.Y., Y.L. and A.T.S.W. wrote the manuscript with the input and comment from all co-authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Kai Chang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Buckling dependent electronic properties of BP-Bi.

a,b, Band structure of BP-Bi with no atomic buckling (Δh = 0). The size of the red (blue) circles represents the contributions of the pz orbital of sublattice A (B). The identical distribution of pzA and pzB orbital illustrates the degeneracy of A and B sublattice due to the centrosymmetric atomic structure. c, Band-edge positions of infinite periodic BP-Bi with different atomic buckling (Δh) at free-standing mode.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Moiré pattern and domain wall in BP-Bi single layer.

a, STM image of BP-Bi island that contains two different ferroelectric domain walls, partly marked by H (head-to-head domain wall) and T (tail-to-tail domain wall) (setpoint: V = 0.4 V, I = 10 pA). b,d, Zoom-in STM images of two typical moiré patterns formed by aligning the \([0\bar{1}]\) of BP-Bi to the zigzag direction (b) or armchair direction (d) of the graphite substrate with a small angle θ (setpoint: b, V = 0.1 V, I = 100 pA; d, V = −0.1 V, I = 100 pA). Their stacking models are shown in (c) and (e), respectively. f,g, STM (f) and AFM (g) images show the closest 180° head-to-head (H) and tail-to-tail (T) domain walls in the same area (setpoint: f, V = 0.3 V, I = 10 pA). h, Buckling (Δh) measurement perpendicularly crossing H and T domain wall in (g). Tip height z = −230 pm in (g,h) relative to the height determined by the setpoint V = 100 mV, I = 10 pA above normal Bi surface. All the orange arrows in (a) and (g) denote the direction of polarization.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Tip height dependent AFM imaging.

a–e, AFM images of a normal area measured at tip height z = −290 pm (a), −270 pm (b), −250 pm (c), −230 pm (d), −200 pm (e). The atomic model to this structure can be found in Fig. 1a in the main text. f–i, AFM images of a 41° inclined 180° head-to-head domain wall measured at tip height z = −270 pm (f), −250 pm (g), −230 pm (h), −210 pm (i). j, Schematic ball-and-stick model illustrates the top two layers of the atomic structure in (f–i). k-n, Atomic AFM images of the 41° inclined 180° tail-to-tail domain wall measured at tip height z = −270 pm (k), −250 pm (l), −230 pm (m), −210 pm (n). o, Schematic ball-and-stick model demonstrates the top two layers of atomic structure in (k–n). The topmost atoms are coloured to light blue to guide the eye. z = 0 pm is defined by the setpoint of V = 100 mV, I = 10 pA above normal Bi surface. All the schematics in (j) and (o) do not reflect the real relative height, as the buckling is gradually changing near the wall.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Band structure measurement of BP-Bi near the Fermi surface.

a, A typical dI/dV spectrum acquired on the BP-Bi shows a band gap above the Fermi surface (initial setpoint: V = 500 mV, I = 1.0 nA). b, STM image (V = −70 mV, I = 150 pA) of a single domain area. c,d, dI/dV maps (left panel) and Fourier-transformed dI/dV maps (right panel) of conduction band (c) and valence band (d) are measured at the area in (b). The atomic Bragg peaks are highlighted by the red dashed circles. e,f, dI/dV line maps (left panel) and corresponding energy-resolved Fourier transformation (right panel) for the conduction band (e) and valence band (f) along the armchair direction (initial setpoint: V = 500 mV, I = 1.3 nA (e); V = −350 mV, I = 1.0 nA (f)). The parabolic fittings and trajectories (red dashed lines) for the dI/dV measurements at VBM and CBM are shown in corresponding insets (V = 400 mV, I = 15 pA (e); V = 450 mV, I = 15 pA (f)).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Buckling and edge measurement of BP-Bi.

a, AFM image of a sub-nanometer scale crater in the BP-Bi. b, Δf(z) spectra measured at the locations of A, B and C in (a). c, The Δf(z) spectra of A and B after subtracting the background curve C. d, Δf(z) spectra of A and B after further background force calibration. e, STM image of monolayer BP-Bi that contains both types of zigzag edges (setpoint: V = −0.2 V, I = 10 pA). f–h, Atomic-resolved AFM (f,h) and STM (g) images show the reconstructed atom arrangement at both sides (setpoint: g, V = 0.2 V, I = 100 pA). Tip height z = −240 pm (a), −250 pm (b), −280 pm (f,h), relative to the height determined by the setpoint V = 100 mV, I = 10 pA above normal Bi surface.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Extra data of electron redistribution by STM and KPFM measurement.

a,b, At the identical area of Fig. 2a in the main text, dI/dV maps at other energy show the same DOS reversal between the valence band (a) and conduction band (b). c,d, The calculated charge density distribution of the valence band (c) and conduction band (d) of pz at the Γ point. e,f, dI/dV maps of the valence band (e) and conduction band (f) measured by a metallic tip apex. Large-scale bumps and depressions come from the moiré pattern. Blue dotted circles and red dotted circles represent the A and B sublattice, respectively. g, AFM image of a normal area away from the domain walls. h,j, Histograms of LCPD measured in a 1.5 × 1.5 Å2 square (8 × 8 grid) centred above the A atom (h) and B atom (j) in (g). The difference of the two Gauss peaks is 13 mV. i, AFM profile (blue) and KPFM measurement (red) along the same trajectory marked by the red dashed arrow in (g). Tip height z = −150 pm (a,b,e), −200 pm (f), −230 pm (g), −80 pm (h–j), relative to the height determined by the setpoint V = 100 mV, I = 10 pA above normal Bi surface.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Extra data of the ferroelectric domain reversal.

a, AFM image of a bent 180° head-to-head domain wall. b,c, AFM images acquired in the right (b) and left (c) red rectangle in (a) during the manipulation. Red dots show the tip position for the domain manipulation. The red arrow labels an atomic defect. d, Tunnelling current during the forward (blue series curves) and backward (red series curves) bias sweeping at different tip-sample distance (Δz = 0 pm to 70 pm). The inset hysteresis loop schematically shows how the polarization of BP-Bi in the middle part is switched. e, Schematics show the position of the domain wall after the forward bias sweeping (right panel) and the backward bias sweeping (left panel). f, Extracted tip height-dependent switching voltages on the positive bias side (VSW2) and negative bias side (VSW1) from (d). g,h, Calculations of the tip height-dependent electric field evolution on the positive bias side (g) and negative bias side (h). Tip height z = −210 pm (a), −230 pm (b,c), and the initial tip height (Δz = 0) in (d) is −50 pm, relative to the height determined by the setpoint V = 100 mV, I = 10 pA above normal Bi surface.

Extended Data Fig. 8 STM and AFM images of other types of domain walls.

a–c, STM images (left panel), AFM images (middle panel) and corresponding atomic models (right panel) of the 54° inclined 180° head-to-head domain wall (a), 90° head-to-tail domain wall (b) and 90° head-to-head domain wall (c). Orange arrows denote the directions of polarization. Setpoints of the STM images in (a–c) are V = 100 mV, I = 10 pA (a), V = 100 mV, I = 30 pA (b), V = 100 mV, I = 50 pA (c). Tip heights to measure the AFM images in (a–c) are z = −250 pm (a), −250 pm (b), −200 pm (c), relative to the height determined by the setpoint V = 100 mV, I = 10 pA above normal Bi surface.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Temperature dependent phase transition.

a–i, At the same area (marked by the defect in the right side of the scanning window), STM images above (a,d,g) and below (b,e,h) the Fermi level are measured at 136 K (a,b), 165 K (d,e) and 210 K (g,h). As labelled in (b,e,h), the dI/dV spectra at corresponding three temperatures 136 K (c), 165 K (f) and 210 K (i) are acquired above the 180° head-to-head domain wall (red) and a normal place (black). j, The structure model of the moiré pattern in this measured area shows how the 180° head-to-head domain wall induce a shift in the moiré superlattice (highlighted by the blue line). Only the top two layers of Bi atoms are included in the model for clarity. k, Line profile along the red dashed arrows in (a,d,g). Setpoint: V = 100 mV, I = 100 pA (a,d,g); V = −100 mV, I = 100 pA (b,e,h); V = −300 mV, I = 200 pA (c,f,i).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Sections 1–9, Figs. 1–9 and Tables 1 and 2.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gou, J., Bai, H., Zhang, X. et al. Two-dimensional ferroelectricity in a single-element bismuth monolayer. Nature 617, 67–72 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-05848-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-05848-5

This article is cited by

-

Stoner instability-mediated large magnetoelectric effects in 2D stacking electrides

npj Computational Materials (2024)

-

Ferrielectricity controlled widely-tunable magnetoelectric coupling in van der Waals multiferroics

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Atomic-scale manipulation of polar domain boundaries in monolayer ferroelectric In2Se3

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Robust multiferroic in interfacial modulation synthesized wafer-scale one-unit-cell of chromium sulfide

Nature Communications (2024)

-

The unique spontaneous polarization property and application of ferroelectric materials in photocatalysis

Nano Research (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.