Abstract

The intertwined ferroelectricity and band topology will enable the non-volatile control of the topological states, which is of importance for nanoelectrics with low energy costing and high response speed. Nonetheless, the principle to design such system is unclear and the feasible approach to achieve the coexistence of two parameter orders is absent. Here, we propose a general paradigm to design 2D ferroelectric topological insulators by sliding topological multilayers on the basis of first-principles calculations. Taking trilayer Bi2Te3 as a model system, we show that in the van der Waals multilayer based 2D topological insulators, the in-plane and out-of-plane ferroelectricity can be induced through a specific interlayer sliding, to enable the coexistence of ferroelectric and topological orders. The strong coupling of the order parameters renders the topological states sensitive to polarization flip, realizing non-volatile ferroelectric control of topological properties. The revealed design-guideline and ferroelectric-topological coupling not only are useful for the fundamental research of the coupled ferroelectric and topological physics in 2D lattices, but also enable innovative applications in nanodevices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ferroelectricity and band topology are two intensively investigated yet distinct properties of insulators1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Physically, there is no inherent exclusion between them due to different origins of polarization and band inversion, their coexistence in a single material leads to the concept of ferroelectric topological insulator (FETI)3,13,14,15. The past years have witnessed the discovery of FETIs, especially in three dimensional, including strained CsPbI316, strained LiZnSb17, pressured or strained AMgBi14, and alloyed KMgBi18, and the induced intriguing electronic properties such as ferroelectric controlled spin vortex. The strongly coupled ferroelectric and topological orders render them both fundamentally intriguing and practically appealing to be used in potential devices.

Unlike 3D FETIs, two-dimensional (2D) lattices with intertwined ferroelectric and topological orders are rather scarce3,19,20,21, and the coupling of the order parameters are also quite weak in several existing cases15,22,23. This is partly due to that, the ferroelectricity in 2D materials has been mainly established in the single-layer asymmetric structures24,25, while band topology is commonly seen in the materials with heavy elements and strong spin orbital coupling. There, the requirements of symmetrical structure with switchable polarization and band inversion with different parity in the revealed 2D material family have to be simultaneously satisfied, to build the 2D FETIs, which significantly restrict the possible realization of 2D FETIs9,26,27,28. So far, how to expand the scope for material candidates of 2D FETIs, especially with intertwined ferroelectric and topological physics, remains an open question.

The intriguing model of sliding switchable interfacial ferroelectricity has been proposed theoretically29 and recently confirmed experimentally30,31,32, which serves as a good starting point for realizing 2D FETI. Here, based on first-principles calculations, we fill aforementioned outstanding gap by introducing a general and simple scheme to realize 2D FETIs with intertwined ferroelectric and topological physics. By studying an example system of trilayer Bi2Te3, we discover that through a specific interlayer sliding, the charge rearrangement brings the spatial electron-hole separation in van der Waals multilayer based 2D topological insulators. The resultant reversal separation leads to the appearance of both in-plane and out-of-plane ferroelectricity, while the nontrivial topological phase is well reserved, thus enabling the coexistence of ferroelectric and topological orders. The strong coupling between ferroelectric and topological orders is also observed, distinct different topological physics can be induced in such multilayer systems when the ferroelectric polarization is reversed, suggesting the ferroelectric controlled topological properties.

Results

Ferroelectric and topological orders

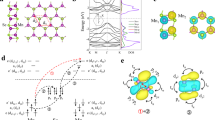

The proposed scheme to realize 2D FETIs with intertwined ferroelectric and topological physics is schematically presented in Fig. 1. Without losing generality, we start from 2D van der Waals multilayers with nontrivial topological properties, the time-reversal symmetry is preserved. Unlike band topology that links with electronic properties1,4,10,33, ferroelectricity relates to crystal structure symmetry and electric dipole induced by electron distribution34,35,36,37,38. To realize ferroelectricity, the polarization has to be switchable. As illustrated in the upper part of Fig. 1, if the in-plane (IP) and out-of-plane (OPP) mirror symmetries (MIP/OOP), as well as the inversion symmetry (I), of the 2D multilayer are broken, the ferroelectricity occurs as long as the polarization is switchable, yielding the 2D FETI. The polarization switching is obtained via interlayer translation. If the polarization is unswitchable, it is just a normal 2D TI, without showing ferroelectric order. On the other hand, when the 2D multilayer possesses MIP/OOP or I symmetry, as illustrated in the lower part of Fig. 1, two different cases can be induced by the interlayer sliding. In first case, the systems like bilayer possess the spatial I symmetry there is no polarization, this configuration is out of our consideration. In second case, the MIP/OOP and I symmetry can be broken by interlayer sliding, the polarization thus appears, and obviously such polarization is electrically switchable. In the latter case, considering that the topological property of the multilayer may be disturbed by the sliding39,40, if the topological property is preserved, the ferroelectric-topological phases can be achieved; otherwise, it is only a trivial 2D ferroelectric material. As we will show below, the obtained ferroelectric and topological orders in such systems exhibits a strong coupling. This design scheme suggests that the crystal symmetry can be utilized as one screening factor to identify 2D FETIs with intertwined ferroelectric and topological physics.

Schematic diagram for designing 2D FETIs from 2D van der Waals multilayers with nontrivial topological properties. Both topological and ferroelectric phases are determined by the mirror and inversion symmetry (MIP/OOP&I) of multilayer. Blue cross denotes the situation that is not under consideration.

Following the design scheme, we study the coexistence of FE and band topology in a real material of trilayer Bi2Te3. Our first-principles calculations are performed based on density functional theory as implemented in the Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP)41. Figure 2a shows the crystal structure of trilayer Bi2Te3 (α-Bi2Te3), which are obtained by direct exfoliating from the bulk phase. It shows a space group of \(D_{3d}\) with symmetry elements (E, 2C3, 3\(C_2^1\), i, 2S6, 3\(\sigma _{{{\mathrm{d}}}}\)). Clearly, the inversion symmetry prevents it from hosting any polarization. We thus slide the upper and lower quintuple layer (QL) along the [1\(\bar 1\)0] and [\(\bar 1\)10] directions, respectively, which are referred to as β1- and β2-Bi2Te3, respectively, as shown in Fig. 2b and Supplementary Note 1. Such interlayer sliding reduces the space group of trilayer Bi2Te3 to C3V with symmetry elements (E, 3C3 and 3σd). Due to the simultaneous absence of I and Mz symmetries, β1- and β2-Bi2Te3 host a spontaneous electric polarization of −5.1 × 109 e cm−2 and 5.1 × 109 e cm−2, respectively, along the out-of-plane (OOP) direction. Obviously, these two polarized configurations can be switched to each other by electric field triggered middle QL sliding [(Fig. 2b]), and thus correlate to two ferroelectric states, suggesting the OOP ferroelectricity.

Crystal structures of trilayer Bi2Te3 with (a) inversion symmetry and c broken inversion symmetry. Teu and Tel represent the bottom Te sublattice of upmost Bi2Te3 QL and top Te sublattice of lowest Bi2Te3 QL, respectively; Teu denotes the middle Te sublattice of central Bi2Te3 QL. b Crystal structures of β1- and β2-Bi2Te3 as well as the schematic diagram of ferroelectric switching. Blue arrows denote the location of interfacial Te atoms of outmost layers. Right parts in a, b show the zoomed-in interfacial atomic layers and the equatorial plane projection of point group. d Charge density difference and e planar average electrostatic potentials along the [001] direction for β1-Bi2Te3. f Minimum energy path for ferroelectric polarization reversal between β1- and β2-Bi2Te3.

To get more insight into the OOP ferroelectricity, we investigate the underlying physics for the electric polarization. In β1-Bi2Te3, as displayed in Fig. 2c, the Teu atom sits above the Bi1 atom, while the Tel atom lies right below the Tec atom. The inequivalent distribution of these atoms gives rise to the spatial electron-hole separation along the OOP direction [Fig. 2d], yielding an electric polarization pointing -z direction. The resultant polarization is also suggested by the calculated planar average electrostatic potential of β1-Bi2Te3 along the [001] direction. As shown in Fig. 2e, there is a discontinuity (ΔV) of 34 meV between the vacuum levels of the upper and lower QL layers, confirming the formation of electric polarization pointing -z direction. While in β2-Bi2Te3, the Teu atom shifts to above the TeT atom, while the Tel atom shifts right below the Bi2 atom; see Fig. 2b. Accordingly, the distribution of these atoms, as well as the spatial electron-hole separation, in β2-Bi2Te3 is reversed with respect to that of β1-Bi2Te3. Such reversal produces an electric polarization pointing to +z direction for β2-Bi2Te3, which are confirmed by the calculated planar average electrostatic potential (ΔV = −34 meV). To evaluate the feasibility of the OOP ferroelectricity in trilayer Bi2Te3, we study the minimum energy path for the ferroelectric switching, which are shown Fig. 2f. The energy barrier is estimated to be 69.46 meV per unit cell, which is comparable to the values of other ferroelectrics37,42,43,44,45, indicating its feasibility.

By further examining the distribution of these atoms in the (110) plane [Fig. 2c], we can see that, for β1-Bi2Te3, the distance between Teu and Tec atoms in the [1\(\bar 1\)0] direction is larger than that between Tel and Tec atoms. Such imbalance distribution also generates the spatial electron-hole separation along the [1\(\bar 1\)0] direction, yielding an in-plane (IP) electric polarization of 3.1 × 1010 e cm−2 pointing to [1\(\bar 1\)0] direction. When transforming β1-Bi2Te3 into β2-Bi2Te3, the Tec atom moves close to Teu in the [1\(\bar 1\)0] direction. In this regard, the spatial electron-hole separation in the [1\(\bar 1\)0] direction is reversed, inducing an IP electric polarization of −3.1 × 1010 e cm−2 pointing [\(\bar 1\)10] direction. The reversal of IP electric polarization shares the same energy path as the OOP case. It should be emphasized that, similar to single-layer In2Se346,47, there are three equivalent IP polarizations along the [1\(\bar 1\)0], [\(\bar 1\bar 2\)0] and [2\(\bar 1\)0] directions, which leads to a zero net IP polarization. However, introducing the substrate proximity effect can readily break the threefold rotation symmetry, realizing the IP ferroelectricity, which has been well demonstrated in experiments38,48,49,50. Accordingly, both IP and OOP ferroelectricity can be expected in trilayer Bi2Te3.

It is important to emphasize that, it is feasible to engineer ferroelectricity in trilayer Bi2Te3. First, the phonon dispersions without imaginary phonon modes (Supplementary Fig. 1) and negative cohesive energy of −2.97 eV/atom confirm the stability of β1-Bi2Te3. And secondly, sliding ferroelectricity and stacking manipulation have been well established in experiments30,31,32. The tear-and-stack method, for example, that pick up one layer and then stamp it on top of the remaining part can be used to precisely fabricate the large-scale commensurate trilayer Bi2Te3 with intercorrelated ferroelectricity30,31.

Next, we study the electronic properties of trilayer Bi2Te3 in the ferroelectric phase. As β1- and β2-Bi2Te3 are linked as two equivalent ferroelectric states, here we take β1-Bi2Te3 as an example. Supplementary Fig. 2a shows the band structure of β1-Bi2Te3 without including spin-orbit coupling (SOC), from which we see that it is an indirect gap semiconductor with a global gap of 0.51 eV near the Γ point. By analyzing orbital contributions, we find the highest valence bands (VB) near the Fermi level is mainly contributed by Te-p orbital, while Bi-p orbital makes the dominate contribution to the lowest conduction bands (CB). Upon taking SOC into account, the VB and CB bands near the Γ point experience a significant Rashba spin splitting [Supplementary Fig. 2b], which can be attributed to the existence of OOP electric polarization in β1-Bi2Te3. The corresponding Rashba parameter is calculated to be \(\alpha _{{{\mathrm{R}}}} = \frac{{2E_{{{\mathrm{R}}}}}}{{{{{\mathbf{k}}}}_0}} = 0.67\;{{{\mathrm{eV}}}}\)Å. When SOC effect is considered, it is interesting to notice that the CBM and VBM move closer and the band gap is reduced to 9 meV. Such band narrowing and M-shaped VBM normally indicates a nontrivial topological phase.

To confirm the nontrivial topological order in β1-Bi2Te3, we calculate the topological invariant Z2. Due to its broken inversion symmetry, the Z2 invariant is calculated by tracing the Wannier charge center (WCC) using non-Abelian Berry connection51. The Wannier functions (WFs) related with lattice vector R can be written as:

Here, a WCC is defined by the mean value of \(< 0_{{{\mathrm{n}}}}|\hat X|0_{{{\mathrm{n}}}} >\), where the \(\hat X\) represent the position operator and .. is the state corresponding to a WF in the cell with R = 0. Then we obtain:

Assuming \(\mathop {\sum }\nolimits_\alpha \bar x_\alpha ^S = \frac{1}{{2\pi }}\mathop {\int }\nolimits_{BZ}\, A^S\) with S = I or II, the summation in α is the occupied states and A is Berry connection. So we get the Z2 invariant following

The calculated evolution of WCC is shown in Fig. 3a. As expected, the WCC is crossed by any arbitrary horizontal reference lines an odd number of times, indicating Z2 = 1. This firmly confirms the nontrivial topological phase of β1-Bi2Te3. As the existence of the localized metallic helical edge channels is the prominent feature for 2D TI, we calculate the armchair edge states by using a tight-binding (TB) Hamiltonian in the maximally localized WF. As shown in Fig. 3b, a pair of edge states around the edge projected Γ-point are observed within the bulk gap. And these states are robust and spin helical, where opposite spin polarizations are propagated along the different directions. The topological edge states further manifest the nontrivial properties. As a result, the coexistence of ferroelectric and topological orders is obtained in trilayer Bi2Te3.

a Evolution of the WCC along ky for β1-Bi2Te3. b TB band structure of armchair-edged nanoribbon of β1-Bi2Te3 obtained by MLWFs, showing edge states inside the gap of bulk bands. c Proposed electrical switch of the chirality and direction of the spin-locked current at boundary. d Schematic representation of 2D FETI with two polar TI states.

Ferroelectric-topological coupling

In the following, we discuss the coupling of ferroelectricity and topological orders in trilayer Bi2Te3. Different from 2D TI with inversion symmetry, due to the existence of IP electric polarization, the characters of the nontrivial edge states contributed by two opposite zigzag edges would be remarkably anisotropic. Taking the edge states along [1\(\bar 1\)0] and [\(\bar 1\)10] as examples, we show them in Supplementary Fig. 3. As expected, these two edge states are distinctly different. Under the ferroelectric switching, these two different nontrivial edge states would be exchanged. This means that the character of nontrivial edge state, such as the position of Dirac point, at an assigned edge can be precisely controlled by ferroelectricity. Moreover, because of the coupling between IP and OOP ferroelectricity, either IP or OOP external electric field can trigger such modulation. This results in the coupled ferroelectric and topological physics in such multilayer systems. Benefit from such ferroelectric-topological coupling, the fascinating topological p-n junctions can be easily obtained when forming a side-by-side ferroelectric domain walls with opposite polarizations52,53,54. In addition, utilizing the either IP or OOP external electric field, such topological p-n junctions are controllable.

Meanwhile, for such multilayer exhibiting weakly coupled vdW interface, the electric field induced transition between two equivalent structural variants with opposite electric polarization could be regarded as a lateral sliding of central Bi2Te3 QL with respect to the outmost Bi2Te3 QLs. The ferroelectric reversal operation acts as a 180° rotation with respect to the direction perpendicular to both IP and OOP polarizations. That’s to say, the two ferroelectric states with opposite polarizations as well as the boundary morphology are linked together through an inversion operation. Besides, IP electric dipole reversal also switches the spin polarization of electronic states34,55, which switches the spin currents at the boundaries. As a result, as shown in Fig. 3c, the chirality as well as the direction of the spin-locked currents at boundaries are closely associated with the direction of ferroelectric polarization, and the direction of topological spin current can be fully controlled by ferroelectricity, which would promote exotic applications in conceptually multifunctional devices. Moreover, due to the direction of spin-locked current can be viewed as a ferroic order, such multilayers can also be treated as multiferroic systems, see Fig. 3d, holding potential for highly efficient multiferroic devices.

Discussion

It should be noted that, the coupled properties are robust in ferroelectric multilayer TIs with different layer number, as long as the polarization reversal in multilayers could be regarded as an inversion operation. We also wish to stress that these coupled ferroelectric and topological physics are not limited to trilayer Bi2Te3, but applicable for all 2D FETIs designed by this scheme.

In summary, we introduce a general scheme to realize coupled ferroelectric and topological physics in multilayer systems. Taking trilayer Bi2Te3 as an example, we show that through a specific interlayer sliding, both IP and OOP ferroelectricity can be realized in van der Waals multilayer based 2D topological insulators, resulting in the coexistence of ferroelectric and topological orders. We further show that the ferroelectric and topological orders exhibit a strongly coupling. Under the ferroelectric switching, distinct different topological physics can be induced in such multilayer systems.

Methods

Density functional theory calculations

First-principles calculations are performed based on density functional theory as implemented in the Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP)41. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) in the scheme of Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerhof (PBE)56 is used to describe the exchange correlation. PBE-D3 method is employed for taking van der Waals interaction into account57. A 500 eV is adopted for the cut-off energy. A vacuum space larger than 18 Å is employed to eliminate the periodic interactions. Convergence criteria of 10−5 eV and 0.01 eVÅ−1 for energy and forces, respectively, are used. The Brillouin zone integration is sampled with Monkhorst-Pack grids of 9 × 9 × 1. A tight binding (TB) method, based on maximally localized Wannier functions (MLWFs)58, is used to calculate the edge states. Energy barriers of ferroelectric switching are obtained by using nudged elastic band (NEB) method59.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Code availability

The central codes used in this paper are VASP and WANNIER90. Detailed information related to the license and user guide are available at http://www.wannier.org and https://www.vasp.at.

References

Ren, Y., Qiao, Z. & Niu, Q. Topological phases in two-dimensional materials: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 79, 066501 (2016).

Huang, H., Xu, Y., Wang, J. & Duan, W. Emerging topological states in quasi-two-dimensional materials. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 7, e1296 (2017).

Rehman, M. U., Hua, C. & Lu, Y. Topology and ferroelectricity in group-V monolayers. Chin. Phys. B 29, 057304 (2020).

Springer, M. A., Liu, T. J., Kuc, A. & Heine, T. Topological two-dimensional polymers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 2007–2019 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. High-temperature quantum anomalous hall insulators in lithium-decorated iron-based superconductor materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 086401 (2020).

Xu, T. et al. Two-dimensional polar metal of a PbTe monolayer by electrostatic doping. Nanoscale Horiz. 5, 1400–1406 (2020).

Liu, X., Pyatakov, A. P. & Ren, W. Magnetoelectric coupling in multiferroic bilayer VS2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 247601 (2020).

Park, J., Yeu, I. W., Han, G., Hwang, C. S. & Choi, J. H. Ferroelectric switching in bilayer 3R MoS2 via interlayer shear mode driven by nonlinear phononics. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–9 (2019).

Tang, X. & Kou, L. Two-dimensional ferroics and multiferroics: platforms for new physics and applications. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 6634–6649 (2019).

Niu, C. et al. Antiferromagnetic topological insulator with nonsymmorphic protection in two dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 066401 (2020).

Hanke, J. P., Freimuth, F., Niu, C., Blugel, S. & Mokrousov, Y. Mixed Weyl semimetals and low-dissipation magnetization control in insulators by spin-orbit torques. Nat. Commun. 8, 1–8 (2017).

Rangel, T. et al. Large bulk photovoltaic effect and spontaneous polarization of single-layer monochalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 067402 (2017).

Kou, L. et al. Two-dimensional ferroelectric topological insulators in functionalized atomically thin bismuth layers. Phys. Rev. B 97, 075429 (2018).

Monserrat, B., Bennett, J. W., Rabe, K. M. & Vanderbilt, D. Antiferroelectric topological insulators in orthorhombic AMgBi compounds (A = Li, Na, K). Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 036802 (2017).

Kou, L., Ma, Y., Liao, T., Du, A. & Chen, C. Multiferroic and ferroic topological order in ligand-functionalized germanene and arsenene. Phys. Rev. Appl. 10, 024043 (2018).

Liu, S., Kim, Y., Tan, L. Z. & Rappe, A. M. Strain-induced ferroelectric topological insulator. Nano Lett. 16, 1663–1668 (2016).

Narayan, A. Class of Rashba ferroelectrics in hexagonal semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 92, 220101 (2015).

Di Sante, D. et al. Intertwined Rashba, Dirac, and Weyl Fermions in hexagonal hyperferroelectrics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 076401 (2016).

Jiang, X., Feng, Y., Chen, K. Q. & Tang, L. M. The coexistence of ferroelectricity and topological phase transition in monolayer alpha-In2Se3 under strain engineering. J. phys. Condens. Matter 32, 105501 (2020).

Zhang, J.-J., Zhu, D. & Yakobson, B. I. Heterobilayer with ferroelectric switching of topological state. Nano Lett. 21, 785–790 (2020).

Bai, H. et al. Nonvolatile ferroelectric control of topological states in two-dimensional heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 102, 235403 (2020).

Pang, Z.-X. et al. Two-dimensional ligand-functionalized plumbene: A promising candidate for ferroelectric and topological order with a large bulk band gap. Physica E Low Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct 120, 114095 (2020).

Hu, X.-k et al. A two-dimensional robust topological insulator with coexisting ferroelectric and valley polarization. J. Mater. Chem. C. 7, 9406–9412 (2019).

Nam, J., Lee, H., Lee, M. & Lee, J. H. Nonvolatile balanced ternary memory based on the multiferroelectric material GeSnTe2. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 7470–7474 (2019).

Chanana, A. & Waghmare, U. V. Prediction of coupled electronic and phononic ferroelectricity in strained 2D h-NbN: first-principles theoretical analysis. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 037601 (2019).

Fei, R., Kang, W. & Yang, L. Ferroelectricity and phase transitions in monolayer group-IV monochalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 097601 (2016).

Sai, N., Fennie, C. J. & Demkov, A. A. Absence of critical thickness in an ultrathin improper ferroelectric film. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 107601 (2009).

Chang, K. et al. Discovery of robust in-plane ferroelectricity in atomic-thick SnTe. Science 353, 15 (2016).

Li, L. & Wu, M. Binary compound bilayer and multilayer with vertical polarizations: two-dimensional ferroelectrics, multiferroics, and nanogenerators. ACS Nano 11, 6382 (2017).

Stern, M. V. et al. Interfacial ferroelectricity by van der Waals sliding. Science 372, 1462–1466 (2021).

Yasuda, K., Wang, X., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T. & Jarillo-Herrero, P. Stacking-engineered ferroelectricity in bilayer boron nitride. Science 372, 1458–1462 (2021).

Fei, Z. et al. Ferroelectric switching of a two-dimensional metal. Nature 560, 336–339 (2018).

Kane, C. L. & Mele, E. J. Quantum spin Hall effect in graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 226801 (2005).

Osada, M. & Sasaki, T. The rise of 2D dielectrics/ferroelectrics. APL Mater. 7, 120902 (2019).

Tu, Z. & Wu, M. Ultrahigh-strain ferroelasticity in two-dimensional honeycomb monolayers: from covalent to metallic bonding. Sci. Bull. 65, 147–152 (2020).

Li, X., Li, X. & Yang, J. Two-dimensional multifunctional metal-organic frameworks with simultaneous ferro-/ferrimagnetism and vertical ferroelectricity. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 4193 (2020).

Liang, Y. et al. Out-of-plane ferroelectricity and multiferroicity in elemental bilayer phosphorene, arsenene, and antimonene. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 012905 (2021).

Liang, Y., Shen, S., Haung, B., Dai, Y. & Ma, Y. Intercorrelated ferroelectrics in 2D van der Waals materials. Mater. Horiz. 8, 1683–1689 (2021).

Kou, L. et al. Tunable quantum order in bilayer Bi2Te3: stacking dependent quantum spin Hall states. Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 243103 (2018).

Peng, R., Ma, Y., Wang, H., Huang, B. & Dai, Y. Stacking-dependent topological phase in bilayer MBi2Te4 (M = Ge, Sn, Pb). Phys. Rev. B 101, 115427 (2020).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Debela, T. T., Liu, S., Choi, J. H. & Kang, H. S. Electronegativity, phase transition, and ferroelectricity of TeSe2 few-layers. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 32, 045301 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Two-dimensional ferroelectricity and switchable spin-textures in ultra-thin elemental Te multilayers. Mater. Horiz. 5, 521–528 (2018).

Yang, Q., Wu, M. & Li, J. Origin of two-dimensional vertical ferroelectricity in WTe2 bilayer and multilayer. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9, 7160–7164 (2018).

Wang, D. et al. High bipolar conductivity and robust in-plane spontaneous electric polarization in selenene. Adv. Electron. Mater. 5, 1800475 (2019).

Pourfath, M. & Soleimani, M. Ferroelectricity and phase transitions in In2Se3 van der Waals material. Nanoscale 12, 22688–22697 (2020).

Ding, W. et al. Prediction of intrinsic two-dimensional ferroelectrics in In2Se3 and other III2-VI3 van der Waals materials. Nat. Commun. 8, 14956 (2017).

Dai, M. et al. Intrinsic dipole coupling in 2D van der Waals ferroelectrics for gate‐controlled switchable rectifier. Adv. Electron. Mater. 6, 1900975 (2019).

Xue, F. et al. Optoelectronic ferroelectric domain‐wall memories made from a single Van Der Waals ferroelectric. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2004206 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Orthogonal electric control of the out‐of‐plane field‐effect in 2D ferroelectric α‐In2Se3. Adv. Electron. Mater. 6, 2000061 (2020).

Yu, R., Qi, X. L., Bernevig, A., Fang, Z. & Dai, X. Equivalent expression of Z2 topological invariant for band insulators using the non-Abelian Berry connection. Phys. Rev. B 84, 075119 (2011).

Tu, N. H., Tanabe, Y., Satake, Y., Huynh, K. K. & Tanigaki, K. In-plane topological p-n junction in the three-dimensional topological insulator Bi2−xSbxTe3−ySey. Nat. Commun. 7, 13763 (2016).

Wang, J., Chen, X., Zhu, B.-F. & Zhang, S.-C. Topological p-n junction. Phys. Rev. B 85, 235131 (2012).

Shirodkar, S. N. & Waghmare, U. V. Emergence of ferroelectricity at a metal-semiconductor transition in a 1T monolayer of MoS2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 157601 (2014).

Lin, Z., Si, C., Duan, S., Wang, C. & Duan, W. Rashba splitting in bilayer transition metal dichalcogenides controlled by electronic ferroelectricity. Phys. Rev. B 100, 155408 (2019).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Moellmann, J. & Grimme, S. DFT-D3 study of some molecular crystals. J. Phys. Chem. C. 118, 7615 (2014).

Mostofi, A. A. et al. wannier90: a tool for obtaining maximally-localised Wannier functions. Comput. Phys. Commun. 178, 685 (2008).

Henkelman, G. & Jónsson, H. Improved tangent estimate in the nudged elastic band method for finding minimum energy paths and saddle points. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9978 (2000).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 11804190 and 12074217), Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Nos. ZR2019QA011 and ZR2019MEM013), Shandong Provincial Key Research and Development Program (Major Scientific and Technological Innovation Project) (No. 2019JZZY010302), Shandong Provincial Key Research and Development Program (No. 2019RKE27004), Shandong Provincial Science Foundation for Excellent Young Scholars (No. ZR2020YQ04), Qilu Young Scholar Program of Shandong University, and Taishan Scholar Program of Shandong Province.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.M conceived the project. Y.L performed DFT calculations. All authors commented on the manuscript and contributed to its final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, Y., Mao, N., Dai, Y. et al. Intertwined ferroelectricity and topological state in two-dimensional multilayer. npj Comput Mater 7, 172 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-021-00643-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-021-00643-0

This article is cited by

-

Twist-resilient and robust ferroelectric quantum spin Hall insulators driven by van der Waals interactions

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2022)