Abstract

Ionic gating is known as a powerful tool for investigation of electronic functionalities stemming from low voltage transistor operation to gate-induced electronic phase control including superconductivity. Two-dimensional (2D) material is one of the archetypal channel materials which exhibit a variety of gate-induced phenomena. Nevertheless, the device simulations on such ion-gated transistor devices have never been reported, despite its importance for the future design of device structures. In this paper, we developed a drift-diffusion (DD) model on a 2D material, WSe2 monolayer, attached with an ionic liquid, and succeeded in simulating the transport properties, potential profile, carrier density distributions in the transistor configuration. In particular, the simulation explains the ambipolar behavior with the gate voltage comparable to the band gap energy, as well as the formation of p-n junctions in the channel reported in several experimental papers. Such peculiar behavior becomes possible by the dramatic change of the potential profiles at the Schottky barrier by the ionic gating. The present result indicates that the DD model coupled to the Poisson equation is a fascinating platform to explain and predict further functionalities of ion-gated transistors through including the spin, valley, and optical degrees of freedom.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In ion-gated transistors, the electric double layer works as a gate dielectric layer of about 1 nm in thickness, and thus such transistors are called electric double layer transistors (EDLTs) or electrolyte gated transistors. Owing to its strong gate coupling, the operation voltage of EDLTs is dramatically reduced, and also, EDLT enables us to control the electronic phases including superconductivity1. Materials for EDLTs are extremely rich including carbon nanotubes2,3, organic semiconductors4, oxide materials5, two-dimensional (2D) materials such as graphene6,7 and transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs)8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15.

In particular, TMDs have gained interest thanks to the intriguing phenomena coupled the valley and spin degrees of freedom. Thus, TMDs can be applied to electronic and spintronic applications16,17. The TMD transistors are good candidates for the next-generation transistors since TMD semiconductors have enough band gap to switch ON/OFF states and high electron-hole mobilities16,18. Moreover, the short channel effect is suppressed compared to the Si devices since the 2D structure allows easier gate control19. The characteristics of the conventional metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistors (MOSFETs) are discussed mainly on MoS218,19,20,21,22,23,24, WSe225,26,27,28,29,30, and MoTe231,32,33,34.

Ionic gating assists in realizing phenomena which are difficult to achieve in the conventional MOSFETs. The ambipolar behavior is one of those observed in ion-gated TMDs. In particular, hole transport in nominally n-type MoS2 is observed only in EDLTs24. This ambipolar nature allows us to fabricate lateral p–n junctions in the channel without chemical doping and asymmetric metal electrodes11. By applying the source-drain bias voltage higher than the gate bias, the ionic distribution changes, allowing the ambipolar operation. Such ambipolar operation can be achieved also in the conventional transistors25,35,36,37, but the operation voltage is significantly lower than that of the conventional FETs, and is in the voltage range similar to the bandgap energy. This offers an opportunity to determine the band gap directly from the transistor characteristics38. It is also known that the p-n junctions formed in the channel emits circularly polarized light, and furthermore, the circular polarization can be flipped by changing the direction of the injected current13. This enables the generation of the circularly polarized light using the electric field. This circular dichroism is ascribed to the imbalance of K and K′ points in the band structure caused by the voltage39,40. Moreover, the strong electric field induced by the ionic gating yields superconductivity in TMDs due to the high accumulation of carrier1.

To achieve more benefit of the ionic gating, the device operation mechanism of EDLTs should be understood. For theoretical studies of transistor operations, the drift-diffusion (DD) method is known as a powerful tool for device simulation to calculate the transport properties, band profile, and spatial distribution of carriers inside devices. As the down-scaling is employed to realize high performance in conventional transistors, the DD simulation is used to design ideal device structures41. However, there has been no DD simulation reported on the ion-gated transistors of TMDs.

In this work, we developed a 2D layer transistor model including an ionic liquid (IL) as a gate dielectric, based on the DD method and succeeded in simulating the distribution of ions, and the dynamics of electron and holes passing through the metal contacts. We examined the characteristics of ion-gated TMD transistors whose device size is about submicron while the several micron is the common channel size reported in experiments. The simulation shows that the down-scaled ion-gated WSe2 transistor holds ambipolar behavior and the formation of the p–n junctions reported in larger-scale devices13,15,38. We clarified the transport mechanism and the fundamental physics underneath the transistor operation using the band profile and the spatial distribution of ions and carriers obtained by the calculation.

The mechanism of the ambipolar transistor has been discussed theoretically on organic and amorphous materials because it is easy to inject both electrons and holes due to the in-gap states42,43. In single crystalline TMDs, such mid-gap states are absent. On the other hand, previous simulations on ion-gated organic transistors used a fixed capacitance induced by the ionic liquids44,45, which cannot include the variation of the capacitance due to the modification of the ion distribution by the source-drain bias voltage and the back action from the carriers in semiconductors. The general perspective of the ambipolar transport in MOSFETs has been discussed in ref. 46.

Some specific implementations are required to adopt the DD model to the ion-gated transistors. We explain the points which differ from the DD model used for the conventional transistors in the next section. After describing the model, we show the results of device simulations on the ion-gated WSe2 transistors. The current, band profile and ion/carrier density distributions are examined for the unipolar and ambipolar operation.

Results and discussion

Drift-diffusion model for ion-gated transition metal dichalcogenide transistors

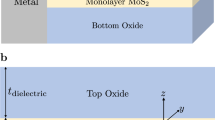

We start with the explanation of the DD model. We consider the 2D layer in (x, y) plane where the transport direction of the channel is set to x. The IL and oxide layer are piled up in the z direction as depicted in Fig. 1. We solve the continuity equation of each currents,

Here, the electron and hole current densities are determined by well-known 1D Drift-Diffusion equations;

where Jn(p) denotes the electron (hole) current densities. q is elementary charge, n(x) [p(x)] is the electron [hole] density at location (x, 0) in WSe2. n(x) and p(x) are defined in units of cm−2. μn(p) is the mobility of the electron (hole) and Dn(p)(x) is the diffusion coefficient. Φ(x, 0) is the potential at position x. R(x) denotes the recombination rate, R(x) = Rdir(x) + RSRH(x) + Rn(p)−con(x). We consider two types of the recombination rate; the direct recombination rate, Rdir(x), and the Shockley-Read-Hall (SRH) recombination rate, RSRH(x), where

and

Here, β is the direct recombination parameter and τ is the recombination time of the SRH recombination. nin is the intrinsic carrier density of electrons and holes. For WSe2, \({n}_{{\rm{in}}}=2{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\frac{\sqrt{{{\rm{m}}}_{{\rm{e}}}{{\rm{m}}}_{{\rm{h}}}{{\rm{m}}}_{0}^{2}}}{\pi {\hslash }^{2}}\exp [-\frac{{E}_{{\rm{g}}}}{2{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T}] \sim 3\times 1{0}^{-6}\) cm−2 at T = 220 K, where me(h) is the effective mass of electrons (holes), m0 is the mass of free electrons, and kB is the Boltzmann constant. Rn(p)−con(x) indicates the generation or annihilation rate of the carriers which enter or exit from the channel at x through the thermionic or tunnel current. Thus, the boundary conditions for n(x) and p(x) are determined by the continuity equation in Eqs. (1), (2). The detailed description of Rn(p)−con(x) is written in the Methods section.

We also solve the Poisson equation in the (x, z) plane in the whole system (WSe2, ILs, SiO2, and the metal contact)

where C(x, z) = i+(x, z) − i−(x, z) for z > 0, C(x, z) = [p(x) − n(x)]/d for −d < z < 0, and C(x, z) = 0 for z < −d. Here, i+(x, z) and i−(x, z) are cation and anion concentrations, respectively (see Methods section for detail). d is the thickness of the WSe2 layer, ϵα is the relative permittivity of the material α (α ∈ WSe2, SiO2, and IL), and ϵ0 is the permittivity of vacuum. \({{\boldsymbol{\epsilon }}}_{{{\rm{WSe}}}_{2}}\) is direction dependent as shown in Table 1. The boundary condition is set to satisfy the continuity of the normal vector of the electric flux density at the interface between materials. The boundary condition at the metal contact is set as Φ(x, tIL) = Vgs + Φ(xs, 0), where tIL is the thickness of IL. At the other edges, we adopt the Neumann’s boundary condition, \(\frac{\partial \Phi (0,z)}{\partial x}=\frac{\partial \Phi ({L}_{x},z)}{\partial x}=\frac{\partial \Phi (x,-{t}_{{{\rm{SiO}}}_{2}}-d)}{\partial z}=0\), where Lx is the length of WSe2 layer in x direction, and \({t}_{{{\rm{SiO}}}_{2}}\) is the thickness of the SiO2. The carrier densities [n(x) and p(x)] in the DD equation and the potential [Φ(x, z)] in the Poisson equation are determined self-consistently in the numerical calculations.

To adopt the above DD model to the ion-gated transistors, there are three points to be noticed regarding the difference between the conventional and ion-gated transistors. Firstly, in Eqs. (3) and (4) the ordinary Einstein relation between the mobility and the diffusion coefficient is not appropriate for ion-gated transistors since the ions attract the high concentration of carriers above 1013 cm−2 while the carrier concentration is usually below 1012 cm−2 in the conventional transistors. Instead, we introduce the generalized Einstein relation (as explained in the Methods section) for the DD model at high carrier concentrations47.

The second point is the treatment of the contact. It is known that metal-TMD junctions usually show the Schottky behavior in the conventional TMD transistors48,49,50 with some exceptions such as ones using graphene or Scandium contacts20,51. The mechanism of the Schottky transport has been precisely studied theoretically52. The conventional TMD transistors also have the problem of the Fermi-level-pinning due to the defect at the TMD-metal junctions50. Thus, only n-type operations have been reported in many works for conventional MoS2 FETs. However, the Fermi-level pinning seems to be weak in the ion-gated TMDs, according to the experimental results13,30. We assume the contact made of an alloy of Ti and Au attached to semiconductor TMDs such as MoS2 and WSe2 acts as the n-type Schottky contact which only injects electrons. However, under the IL, as reported in ref. 13, the carrier of unipolar transport changes from electrons to holes by changing the sign of the gate voltage for small source–drain voltage. Furthermore, the electron current shows the linear increase by applying the source–drain voltage, which indicates the Ohmic contact. Thus, the boundary condition for the Schottky contact is not appropriate for the DD model. Moreover, the boundary condition for the Ohmic contact which can inject either electron and hole is also not appropriate. To realize both Ohmic and ambipolar behavior, we adopt a practical Schottky contact model, which realizes not only the Schottky contact but also the Ohmic contact for both electron and hole carriers53. We expand the model in ref. 53 from 3D structure to the 2D structure that can be applied to thin layer devices.

Thirdly, since the ion has the finite size, there is a limitation of ions per volume in the liquid. Note that the potential becomes too sharp around the interface compared to the real ionic potential if we consider the infinitesimal size of ions. The finite size of ions results in the screening between ions that affect the potential. We adopt the model including the screening effect of IL which can be applied beyond the classical Gouy-Chapman-Stern model54. Note that the model is not applicable to the crowding situation of ions which occurs in the high gate bias voltage55. We explain the concrete description of the model in the Methods section.

Device simulation of WSe2 transistors

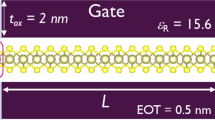

The schematic view of ion-gated monolayer WSe2 transistors considered is depicted in Fig. 1. The employed parameters for the calculation are written in Table 1. The length of WSe2 in the x (channel) direction is set at 100 nm and the source and drain contacts with 10 nm length are attached to the top of WSe2 monolayer. We assume that electrons tunnel between metal contacts and the channel at x = 10 nm and x = 90 nm so that the real channel length is 80 nm. We set the energy difference between the work function of TMD and metal contact to 0.6 eV considering the metal contact made of the alloy of Ti and Au56. In this calculation, we set the Fermi energy of the metal source contact to be zero. The energy level of the bottom of the conduction band is 0.6 eV at the source contact surface while the top of the valence band is −1.0 eV. The thickness of the IL is 10 nm and the metallic gate contact is attached to the top of the IL. The thickness of the SiO2 layer at the bottom of the WSe2 is 10 nm with the Neumann condition. We assume ions such as DEME-TFSI (N,N-diethyl-N-methyl-N- (2-methoxyethyl) ammonium bis (trifluoromethylsulfonyl)-imide) whose size is approximately 1 nm so that we fix the maximum ion concentration on the ion layer at the electric double layer to \({n}_{\max }=1\times 1{0}^{21}\) cm−3. The average ionic concentration is set to ni = 2 × 1020 cm−3. Though the employed ni is lower than the real concentration due to the restriction in the numerical calculation (abrupt change of the carrier and ion concentrations), the approximate maximum of the IL capacitance is 40 μF/cm2, which is large enough to bend the potential and make the Schottky barrier sufficiently thin so that the source and drain contacts show the Ohmic behavior. We use the constant mobility extracted from the experiment in ref. 15. We neglect the Vds dependence of mobility since the potential is relatively flat inside the channel region beside the metal-TMD surface, as described later in the next section. Furthermore, we assume that the concentration of defects inside WSe2 is negligible so that mobility is not affected by carrier concentration tuned by the gate voltage.

We start from examining the transport characteristics of ion-gated WSe2 transistors using the theoretical model. As shown in Fig. 2a, b, the drain-source current, Ids, is calculated as a function of the voltage determined from the potential difference between the source contact and the center of the ionic liquid, Vref = Φ(10, 5 nm) − Φ(10 nm, 0) [see inset of Fig. 2b]. We should mention that Vref is adopted in Fig. 2a, b instead of the gate voltage between the source contact and the metal gate, Vgs, to subtract the potential drop occurs at the surface of the gate contact for the considered system. Note that IL can be considered as two capacitors in series; one is the electric double layer capacitor (EDLC) of the gate electrode and the ionic liquid, and the other is the EDLC of WSe2 and the ionic liquid. The surface area of the metal gate attached to the IL is usually much more substantial in experiments. Since the number of net ions at both capacitors should be the same, the ion concentration at the substantial metal gate is much smaller than the one at the WSe2 surface. Thus, potential drops at the metal gate is negligible. However, in our calculation we set the surface area of the metal gate 100(nm)/80(nm) larger than the one of the WSe2 due to the constraints of the numerical calculation. Thus, approximately half of the potential drops at the metal gate. So we define Vref to compare the results with experiments. The bias voltage between the drain and source electrodes is set at Vds = 0.2 V. Note that the current flows from the drain contact to the source contact when Vds is positive. The center of the off-gate voltage slides to the minus (~ −0.2 V) from the zero point since the energy difference between the metal contact and WSe2 is ΦSB = 0.6 V which is 0.2 V above the center of the band gap. As shown in Fig. 2b, using the linear-scale plot, we estimate the threshold voltage from the intersection point of the line Ids = 0 and the dotted linear line of the current. Here, the dotted line is determined from the least-square method using the data from 1.2 V < Vref <1.5 V for the electron current, and −1.5 V < Vref < −1.3 V for the hole current. The determined threshold voltage is Vth−e = 0.94 V for the electron current, and Vth−h = −1.17 V for the hole current, respectively. The threshold voltages for electrons and holes have been used to measure the bandgap of the semiconductor as reported in ref. 38. In our numerical calculation, the energy difference between the threshold voltages of electron and hole currents is e(Vth−e − Vth−h) = 2.11 eV, which is 0.51 eV larger than the real band gap, Eg.

a The log-scale plot of the current Ids as a function of Vref in the ionic-gated WSe2 transistor. See Table 1 for the other parameters. b The linear-scale plot of the electron (blue) and hole (red) current as a function of Vref. The right vertical axis is set for the electron current and the left vertical axis is set for the hole current. The dotted linear lines are determined by the least-square method using data from 1.3 V < Vref <1.5 V for the electron current and −1.5 V < Vref < −1.3 V for the hole current. The interaction points of Ids= 0 and the linear lines indicate the threshold voltages for the electron and hole currents; Vth−e = 0.94 V, and Vth−h = −1.17 V respectively. c Net carrier concentration for Vref = −2 V (Vref ~ −1.46 V) [dot-dashed line], Vgs = 0.2 V (Vref ~ 0.19 V) [solid line], and Vgs = 2 V (Vref ~ 1.38 V) [dotted line].

Figure 2c shows the distribution of the net carrier concentration inside the channel. The current carrier is only electrons when Vref > 0, while holes become carriers for Vref < 0. Note that minor carrier is negligibly small and can not be determined by the numerical calculation. The carrier density of electrons or holes is almost constant besides the region around the contact.

Top panels in Fig. 3 show two-dimensional plots of the net ion density i+(x, z) − i−(x, z) for Vgs = −2 V (a: Vref ~ −1.46 V), Vgs = 0.2 V (b: Vref ~ 0.19 V), and Vgs = 2 V (c: Vref ~ 1.38 V). At the interface attached to WSe2, anions are dominant for Vref < 0 while cations are dominant for Vref > 0. The band profile of WSe2 coupled to the metal contact is depicted in the bottom panels of Fig. 3. At Vgs = −2 V, the band bending is extremely sharp at the contact, and both bottom of the conduction band and top of the valence band are shifted above the quasi-Fermi energy, φn(p), in the channel. Around the contact-channel junctions, the potential bends downward which induces the Schottky barrier. The IL makes the thickness of the Schottky barrier of the valence band at Fermi level about 0.9 nm for the holes to tunnel through. Note that the quasi-Fermi energy is plotted only for the main carrier since the minor carrier is almost zero due to the rapid reduction of the carrier inside the band gap for WSe2. At Vgs = 0.2 V, the quasi-Fermi level is located inside the band gap. Thus, the tunnel of the carrier between the contact and channel is prohibited. Only the Schottky (thermionic) transport is possible, but the simulation shows that it is negligible at this gate voltage. At Vgs = 2 V, the potential energy of the channel area becomes downward convex. Thus the quasi-Fermi energy is located at the conduction band which results in electron current. The carrier-type switching is possible with much smaller Vgs compared to the case in the conventional transistors. The ions play a role of dopant (surface doping) and induce the n-type contact by making the Schottky barrier of the conduction band at the Fermi level about 0.4 nm so that carriers can tunnel through. The Ohmic behavior is confirmed by the Id-Vds characteristics discussed below. Here, we show that both n-type and p-type operation are possible depending on the direction of the Schottky barrier controlled by the metal gate attached to the IL even if the work function of the metal contact is located at the upper part of the band gap as we set in this simulation.

(Top) Net ion density i+(x, z) − i−(x, z) on the ionic liquid for a Vgs = −2 V (Vref ~ −1.46 V), b Vref = 0.2 V (Vref ~ 0.19 V), and c Vgs = 2 V (Vref ~ 1.38 V). The drain-source voltage is fixed to Vds = 0.2 V. (Bottom) Band profile of WSe2 and the metal. The dotted lines indicate the bottom of the conduction band, Ec (blue), and the top of the valence band, Ev (red). The solid lines denote the quasi-Fermi energy. See Table 1 for the other parameters.

Next, we calculate the Id-Vds characteristics at Vgs = 1.5 V where the carrier type is n-type. We plot the electron (dotted line), hole current (dot-dashed line), and the total current (solid line) as shown in Fig. 4. The Ids-Vds characteristics can be classified to the three regions: the linear (0 ⪅ Vds ⪅ 1.2 V), the saturation (1.2 V ⪅ Vds ⪅ 2.8 V), and the ambipolar region (Vds ⪆ 2.8V). In the linear region, the current increases with Vds approximately linearly around Vds = 0 V, followed by the saturation region starting at Vds ~ 1.2 V. Above Vds ~ 2.8 V, Ids takes off again, indicating the onset of hole current injected from the drain electrode (ambipolar transport). This feature is similar to the experimental output curve of WSe2 device for larger devices13. The increase of electron current in the ambipolar region is due to the recombination of electrons and holes inside the channel.

The gate voltage is fixed to Vgs = 1.5 V. The lines indicate electron (dotted line), hole (dot-dashed line), and total current (solid line). See Table 1 for other parameters.

Figure 5 shows the 2D plot of the net ion density of the IL (top), and band profile of the WSe2 channel and the metal contacts (bottom) for the linear region (a: Vds = 0.5 V), saturation region (b: Vds = 2.5 V) and ambipolar region (c: Vds = 4 V). The figures from d to f are the enlarged views of the potential profile around the contacts. The open arrows denote the tunnel transport while the solid arrows denote the thermionic transport where carriers go beyond the barriers.

a–c (Top) Net ion density i+(x, z) − i−(x, z) on the ionic liquid for a Vds = 0.5 V, b Vds = 2.5 V, and c Vds = 4 V. The gate voltage is fixed to Vgs = 1.5 V. (Bottom) Band profile of WSe2 and the metal. The Fermi-energy of the source contact is set to φmetal = 0. The dotted lines indicate the bottom of the conduction band, Ec (blue), and top of the valence band, Ev (red). The solid lines are the quasi-Fermi energy for electron φn(x) (blue) and hole φp(x) (red). d–f The extension view of the potential profile around the contacts (x = 7–13 nm and x = 87–93 nm) for d Vds = 0.5 V, e Vds = 2.5 V, and f Vds = 4 V. Black lines are the Fermi-level at the metal contacts. The arrows shows the transport direction of electrons (blue) and holes (red). The open arrows indicate the tunnel transport and the solid arrows denote the thermionic transport. The thicker arrows indicate the dominant paths of the current.

In the linear region (Fig. 5a), the cations are dominant at the interface attached to WSe2. Therefore, the current is dominated by electrons since the band gap allows only electrons to tunnel through the metal-WSe2 junctions as depicted in Fig. 5d. By increasing the bias voltage Vds, the electrons tunneling from the channel to the drain contact gains. The inclination of the current in the linear region is estimated to be 7.5 × 10−5 Ω−1. Thus, the estimated contact resistance is Rcon ~ 10 kΩ while the channel resistance is Rch = 1∕qμnn ~ 4 kΩ (n ~ 4 × 1013 cm−2 as discussed below) so that the contact resistance is comparable to the channel resistance, which results in the linear behavior.

In the saturation region, cations are dominant at the interface attached to WSe2 while anions assemble at the drain contact as shown in the top panel of Fig. 5b. The potential energy at the drain contact switches from upward to downward (the bottom panel of Fig. 5b, e). The Fermi-level of the drain contact is located at the energy inside the band gap of the channel so that hole tunneling from the drain contact is limited by the Schottky junction as shown in Fig. 5e. The current is saturated even with increasing the Vds. This pinch-off behavior is also seen in conventional transistors.

Finally, in the ambipolar region, the net ion density changes gradually from the cation dominant to the anion dominant from the source to the drain at the interface attached to WSe2 as shown in Fig. 5c. We find that anions assembled at the drain contact pull down the potential energy around the contact. By increasing Vds, the anions screens hole inside WSe2 which makes the Schottky barrier thinner enough for holes to tunnel through. Furthermore, the Fermi energy of the drain contact goes below the top of the valence band in the channel at the metal-WSe2 junction. Then, there are enough holes to tunnel through the Schottky barrier from the drain contact as depicted in Fig. 5f, which results in the p–n junction. In the p–n junction induced by IL, the drift and diffusion currents always move in the same direction. It means that the p–n junction exists only for the forward bias voltage higher than the built-in potential.

The ambipolar behavior does not occur for the conventional metal-oxide-semiconductor (MOS) transistors with the same Vds. In the Section III of the Supplementary information, we show the current and band profile of the WSe2 MOS transistor, whose oxide layer has the same permittivity with IL (Supplementary Fig. 2a). To fix the carrier concentration to the same order to the ion-gated transistors, we set the gate voltage to Vgs = 10 V so that n ~ 5 × 1013 cm−2 at the equilibrium condition. The current increases monotonously with Vds and the transistor is always n-type as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2b. Supplementary Fig. 3 is the band profile for the MOS transistor. The potential energy decreases linearly at the channel region by applying Vds and the Schottky barrier at the drain area becomes perfect contact for electrons to pass through from WSe2 to the metal. The Fermi energy of the metal contact is located inside the band gap so that the holes cannot pass through the barrier. Thus, the drain contact keeps acting as n-type contact and the current holds unipolar up to Vds = 4 V.

Figure 6 displays the spatial distributions of the net carriers, electrons, and holes at the channel area for the linear region (a: Vds = 0.5 V), saturation region (b: Vds = 2.5 V), and ambipolar region (c: Vds = 4 V). In the linear region, the electron density slightly varies around n ~ 4 × 1013 cm−2. In the saturation region, on the other hand, the electron densities are not constant anymore, and a depletion point appears at the drain contact. There are a few numbers of holes as shown in the inset of Fig. 6b (p ~ 108 cm−2) which is injected from the drain contact by the thermionic transport although the hole tunneling is prohibited in the saturation region. In the ambipolar region, electrons and holes are spread throughout the whole channel area so that small difference between the electron and hole concentrations make the p-n junction. Therefore, the electrons and holes can recombine in the whole area of the channel as shown in the Supplementary Fig. 1 of the Supplementary information (Section II). There is no depletion region when the applied voltage is higher than the built-in potential. Then, the potential drop at the p–n junction is determined by the recombination zone. The size for the recombination zone is estimated to be \(1/\sqrt{\beta /{D}_{{\rm{n}}}\max [p(x)]} \sim\) 1 μm in our case. Thus, the channel size we consider is much smaller than the recombination region. It leads to no potential change at the cross-section between n and p regions.

The application of the ion-gated TMD transistors can be very broad, stemming from light emitting devices13,57, superconductivity58, to thermoelectric properties59. Here, we pick up transistors that emits circularly polarized light owing to the peculiar electronic structure of TMDs. Since there has been no simulation model constructed in this area, the essential physical factor in determining the performance of the light-emitting device is yet not known. This simulation method is advantageous to explore the crucial factors and design the ideal device structure. We can examine the characteristics of light emission by calculating the recombination rate, as demonstrated in Section II of Supplementary Information. In the simulation, the parameters presented in Table 1 can be tuned to explore the crucial factors. These factors can also be realized in experiments by changing the materials and device structures.

In conclusion, we have developed the DD model for the ion-gated TMD transistors and explained the characteristic transport behavior of the ion-gated WSe2 transistors. We adopt the DD model coupled to the Poisson equation for calculating the band profile, carrier densities, and current. In the Poisson equation, the model including the screening effect of charge is employed to derive the potential profile of the IL. In the DD model, the generalized Einstein relation is considered for high carrier densities and the model of the practical Schottky contact is employed for considering the Schottky and Ohmic behavior of the transistors. One of the peculiar features of ion-gated transistors of 2D materials is the ambipolar behavior with the application of the gate voltage comparable to the band gap energy. The simulation explains the fundamental physics underneath for ambipolar transport and the formation of p–n junctions in the channel. The present result indicates that the DD model coupled with the Poisson equation is a fascinating tool to study ion-gated transistors. By including the spin, valley, and optical degree of freedom to the DD model, we can examine the functionality and to design the device structure of ion-gated transistors.

Methods

We introduce the concrete explanation of the models. In the DD equation, Eqs. (3) and (4), Dn(p)(x) is not described using the ordinary Einstein relation since the Boltzmann distribution is not satisfied in the considered system due to the high carrier concentration above 1013 cm−2. Then, we adopt the generalized Einstein relation for the DD model47. The generalized Einstein relation which obeys the Fermi distribution is expressed as

where

Here, φn(p) is the quasi Fermi potential of electrons (holes). kB is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the temperature. Note that gn(p) = 1 for the ordinary Einstein relation.

For realizing the practical Schottky contact, we consider the thermionic current and tunnel current passing through the metal-TMD junctions. For the thermionic current density of electrons at the source (drain) contact is written as

while the thermionic current density of holes is

Here, \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{1/2}\) is the Fermi integral

where Γ(x) is the gamma function. A2D is the Richardson constant for the 2D materials60,

Ec(x) and Ev(x) denote the energy at the bottom of the conduction band and the top of the valence band, respectively. φmetal−s(d) is the Fermi energy of the source (drain) metal contact. Two is the factor stemmed from the valley degree of freedom of the monolayer TMD. We should mention that the thermionic current is considered only at the junction between the source (or drain) contact and channel, xs(xd). The tunnel current densities at x from source (drain) contact for electrons and holes are written as

and

respectively, where Te−s(d)(ϵ) and Th−s(d)(ϵ) are the transmission probability of the electrons and holes tunneling through the source (drain) contact and channel derived by the WKB approximations written as

respectively. Here, E(x) = −dΦ(x, 0)∕dx is the electric field in the x direction. Note that Te−s(d)(ϵ) and Th−s(d)(ϵ) are finite only when the arguments inside the exponential functions are negative. In the numerical calculation, the Fermi integral \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{1/2}\) and \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{-1/2}\) has been obtained by using the approximation method based on the Sommerfeld expansion61. The electron (hole) current injected from contacts is included in the current continuity equation through the recombination rate as

The total recombination term is written as R(x) = Rdir(x) + RSRH(x) + Rn(p)−con(x).

The ion distributions in the Poisson equation, Eq. (7), are expressed as

and

γ is the screening parameter of the ions stemmed from the finite size of ions. \(\gamma ={n}_{{\rm{i}}}/{n}_{\max }\) where \({n}_{\max }\) is the maximum concentration of both cation and anion which can pack in the liquid. Here we define shifted potential, \({\Phi }^{\prime}(x,z)\), since Φ(x, z) is set to be zero reference to the Fermi energy of the source contact. \({\Phi }^{\prime}(x,z)\) and the coefficient of carrier concentration, ns, are determined to satisfy the condition

where Aion is the area of the ion. Note that the average carrier concentration, ni, is constant since there is no electrodes to supply ions in the system.

In the numerical calculation, the Scharfetter-Gummel discretization is used for solving the DD equation which is described in the Section I of the Supplementary information.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

11 February 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-020-0314-9

References

Saito, Y. et al. Superconductivity protected by spin-valley locking in ion-gated MoS2. Nat. Phys. 12, 144–149 (2016).

Krüger, M., Buitelaar, M. R., Nussbaumer, T., Schönenberger, C. & Forró, L. Electrochemical carbon nanotube field-effect transistor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 78, 1291–1293 (2001).

Rosenblatt, S. et al. High performance electrolyte gated carbon nanotube transistors. Nano Lett. 2, 869–872 (2002).

Ono, S., Seki, S., Hirahara, R., Tominari, Y. & Takeya, J. High-mobility, low-power, and fast-switching organic field-effect transistors with ionic liquids. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 103313 (2008).

Yuan, H. et al. High-density carrier accumulation in ZnO field-effect transistors gated by electric double layers of ionic liquids. Adv. Funct. Mater. 19, 1046–1053 (2009).

Uesugi, E., Goto, H., Eguchi, R., Fujiwara, A. & Kubozono, Y. Electric double-layer capacitance between an ionic liquid and few-layer graphene. Sci. Rep. 3, 1595 (2013).

Chen, F., Qing, Q., Xia, J., Li, J. & Tao, N. Electrochemical gate-controlled charge transport in graphene in ionic liquid and aqueous solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 9908–9909 (2009).

Xu, H., Fathipour, S., Kinder, E. W., Seabaugh, A. C. & Fullerton-Shirey, S. K. Reconfigurable ion gating of 2H-MoTe2 field-effect transistors using poly(ethylene oxide)-CsClO4 solid polymer electrolyte. ACS Nano 9, 4900–4910 (2015).

Perera, M. M. et al. Improved carrier mobility in few-layer MoS2 field-effect transistors with ionic-liquid gating. ACS Nano 7, 4449–4458 (2013).

Pu, J. et al. Highly flexible MoS2 thin-film transistors with ion gel dielectrics. Nano Lett. 12, 4013–4017 (2012).

Zhang, Y. J., Ye, J. T., Yomogida, Y., Takenobu, T. & Iwasa, Y. Formation of a stable p–n junction in a liquid-gated MoS2 ambipolar transistor. Nano Lett. 13, 3023–3028 (2013).

Yuan, H. T. et al. Zeeman-type spin splitting controlled by an electric field. Nat. Phys. 9, 563–569 (2013).

Zhang, Y. J., Oka, T., Suzuki, R., Ye, J. T. & Iwasa, Y. Electrically switchable chiral light-emitting transistor. Science 344, 725–728 (2014).

Lin, M. W. et al. Mobility enhancement and highly efficient gating of monolayer MoS2 transistors with polymer electrolyte. J. Phys. D 45, 345102 (2012).

Zhang, Y., Suzuki, R. & Iwasa, Y. Potential profile of stabilized field-induced lateral p–n junction in transition-metal dichalcogenides. ACS Nano 11, 12583–12590 (2017).

Wang, Q. H., Kalantar-Zadeh, K., Kis, A., Coleman, J. N. & Strano, M. S. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 699–712 (2012).

Zibouche, N., Philipsen, P., Kuc, A. & Heine, T. Transition-metal dichalcogenide bilayers: switching materials for spintronic and valleytronic applications. Phys. Rev. B 90, 125440 (2014).

Yoon, Y., Ganapathi, K. & Salahuddin, S. How good can monolayer MoS2 transistors be? Nano Lett. 11, 3768–3773 (2011).

Radisavljevic, B., Radenovic, A., Brivio, J., Giacometti, V. & Kis, A. Single-layer MoS2 transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 147–150 (2011).

Das, S., Chen, H. Y., Penumatcha, A. V. & Appenzeller, J. High performance multilayer MoS2 transistors with scandium contacts. Nano Lett. 13, 100–105 (2013).

Kim, S. et al. High-mobility and low-power thin-film transistors based on multilayer MoS2 crystals. Nat. Commun. 3, 1011 (2012).

Wang, H. et al. Integrated circuits based on bilayer MoS2 transistors. Nano Lett. 12, 4674–4680 (2012).

Chuang, H.-J. et al. High mobility WSe2 p- and n-type field-effect transistors contacted by highly doped graphene for low-resistance contacts. Nano Lett. 14, 3594–3601 (2014).

Zhang, Y. J., Ye, J. T., Matsuhashi, Y. & Iwasa, Y. Ambipolar MoS2 thin flake transistors. Nano Lett. 12, 1136–1140 (2012).

Podzorov, V., Gershenson, M. E., Kloc, C., Zeis, R. & Bucher, E. High-mobility field-effect transistors based on transition metal dichalcogenides. Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 3301 (2004).

Fang, H. et al. High-performance single layered WSe2 p-FETs with chemically doped contacts. Nano Lett. 12, 3788–3792 (2012).

Liu, W. et al. Role of metal contacts in designing high-performance monolayer n-type WSe2 field effect transistors. Nano Lett. 13, 1983–1990 (2013).

Tosun, M. et al. High-gain inverters based on WSe2 complementary field-effect transistors. ACS Nano 8, 4948–4953 (2014).

Das, S. & Appenzeller, J. WSe2 field effect transistors with enhanced ambipolar characteristics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 103501 (2013).

Chuang, H.-J. et al. High mobility WSe2 p- and n-type field-effect transistors contacted by highly doped graphene for low-resistance contacts. Nano Lett. 14, 3594–3601 (2014).

Lin, Y. F. et al. Ambipolar MoTe2 transistors and their applications in logic circuits. Adv. Mater. 26, 3263–3269 (2014).

Pradhan, N. R. et al. Field-effect transistors based on few-layered α-MoTe2. ACS Nano 8, 5911–5920 (2014).

Fathipour, S. et al. Exfoliated multilayer MoTe2 field-effect transistors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 192101 (2014).

Lezama, I. G. et al. Surface transport and band gap structure of exfoliated 2H-MoTe2 crystals. 2D Mater. 1, 021002 (2014).

Pospischil, A., Furchi, M. M. & Mueller, T. Solar-energy conversion and light emission in an atomic monolayer p–n diode. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 257–261 (2014).

Baugher, B. W. H., Churchill, H. O. H., Yang, Y. F. & Jarillo-Herrero, P. Optoelectronic devices based on electrically tunable p–n diodes in a monolayer dichalcogenide. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 262–267 (2014).

Ross, J. S. et al. Electrically tunable excitonic light-emitting diodes based on monolayer WSe2 p–n junctions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 268–272 (2014).

Braga, D., Lezama, I. G., Berger, H. & Morpurgo, A. F. Quantitative determination of the band gap of WS2 with ambipolar ionic liquid-gated transistors. Nano Lett. 12, 5218–5223 (2012).

Cao, T. et al. Valley-selective circular dichroism of monolayer molybdenum disulphide. Nat. Commun. 3, 887 (2012).

Xiao, D., Liu, G.-B., Feng, W., Xu, X. & Yao, W. Coupled spin and valley physics in monolayers of MoS2 and other group-VI dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 196802 (2012).

Jiménez, D. et al. Drift-diffusion model for single layer transition metal dichalcogenide field-effect transistors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 243501 (2012).

Zaumseil, J. & Sirringhaus, H. Electron and ambipolar transport in organic field-effect transistors. Chem. Rev. 107, 1296–1323 (2007).

Smits, E. C. P. et al. Ambipolar charge transport in organic field-effect transistors. Phys. Rev. B 73, 205316 (2006).

Melzer, K. et al. Characterization and simulation of electrolyte-gated organic field-effect transistors. Faraday Discuss. 174, 399–411 (2014).

Yoo, H. et al. Balancing hole and electron conduction in ambipolar split-gate thin-film transistors. Sci. Rep. 7, 5015 (2017).

Kang, M. S. & Frisbie, C. D. A pedagogical perspective on ambipolar FETs. ChemPhysChem 14, 1547–1552 (2013).

Stodtmann, S., Lee, R. M., Weiler, C. K. F. & Badinski, A. Numerical simulation of organic semiconductor devices with high carrier densities. J. Appl. Phys. 112, 114909 (2012).

Liu, H. et al. Switching mechanism in single-layer molybdenum disulfide transistors: an insight into current flow across schottky barriers. ACS Nano 8, 1031–1038 (2014).

Xu, Y. et al. Contacts between two- and three-dimensional materials: Ohmic, schottky, and p–n heterojunctions. ACS Nano 10, 4895–4919 (2016).

Kim, C. et al. Fermi level pinning at electrical metal contacts of monolayer molybdenum dichalcogenides. ACS Nano 11, 1588–1596 (2017).

Liu, Y. et al. Toward barrier free contact to molybdenum disulfide using graphene electrodes. Nano Lett. 15, 3030–3034 (2015).

Somvanshi, D. et al. Nature of carrier injection in metal/2D-semiconductor interface and its implications for the limits of contact resistance. Phys. Rev. B 96, 205423 (2017).

Matsuzawa, K., Uchida, K. & Nishiyama, A. A unified simulation of Schottky and ohmic contacts. IEEE T. Electron Dev. 47, 103–108 (2000).

Kornyshev, A. A. et al. Double-layer in ionic liquids: paradigm change? J. Phys. Chem. B 111, 5545–5557 (2007).

Bazant, M. Z., Storey, B. D. & Kornyshev, A. A. Double layer in ionic liquids: overscreening versus crowding. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 046102 (2011).

Kang, J., Liu, W., Sarkar, D., Jena, D. & Banerjee, K. Computational study of metal contacts to monolayer transition-metal dichalcogenide semiconductors. Phys. Rev. X 4, 031005 (2014).

Onga, M., Zhang, Y., Suzuki, R. & Iwasa, Y. High circular polarization in electroluminescence from MoSe2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 073107 (2016).

Ye, J. T. et al. Superconducting dome in a gate-tuned band insulator. Science 338, 1193–1196 (2012).

Yoshida, M. et al. Gate-optimized thermoelectric power factor in ultrathin WSe2 single crystals. Nano Lett. 16, 2061–2065 (2016).

Anwar, A., Nabet, B., Culp, J. & Castro, F. Effects of electron confinement on thermionic emission current in a modulation doped heterostructure. J. Appl. Phys. 85, 2663–2666 (1999).

Koroleva, O. N., Mazhukin, A. V., Mazhukin, V. I. & Breslavskiy, P. V. Analytical approximation of the fermi-dirac integrals of half-integer and integer orders. Math. Models Comput. Simul. 9, 383–389 (2017).

Morozov, Y. V. & Kuno, M. Optical constants and dynamic conductivities of single layer MoS2, MoSe2, and WSe2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 083103 (2015).

Liu, W., Cao, W., Kang, J. & Banerjee, K. High-performance field-effect-transistors on monolayer-WSe2. ECS Trans. 58, 281–285 (2013).

Wakai, C., Oleinikova, A., Ott, M. & Weingärtner, H. How polar are ionic liquids? determination of the static dielectric constant of an imidazolium-based ionic liquid by microwave dielectric spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 17028–17030 (2005).

Ghosh, R. K. & Mahapatra, S. Monolayer transition metal dichalcogenide channel-based tunnel transistor. IEEE J. Electron Dev. 1, 175–180 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank K. Yoshida, K. Fukuda, T. Tasai, and J.T. Teherani for useful discussions. This research was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (S) (no. 19H05602) and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (no. 19K05201) from JSPS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.U., Y.Z. and Y.I. conceived the work. A.U. proposed the simulation model and performed the simulation. All authors analyzed the results and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ueda, A., Zhang, Y., Sano, N. et al. Ambipolar device simulation based on the drift-diffusion model in ion-gated transition metal dichalcogenide transistors. npj Comput Mater 6, 24 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-020-0293-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-020-0293-x