Abstract

Fabrication of covalent organic framework (COF) membranes for molecular transport has excited highly pragmatic interest as a low energy and cost-effective route for molecular separations. However, currently, most COF membranes are assembled via a one-step procedure in liquid phase(s) by concurrent polymerization and crystallization, which are often accompanied by a loosely packed and less ordered structure. Herein, we propose a two-step procedure via a phase switching strategy, which decouples the polymerization process and the crystallization process to assemble compact and highly crystalline COF membranes. In the pre-assembly step, the mixed monomer solution is casted into a pristine membrane in the liquid phase, along with the completion of polymerization process. In the assembly step, the pristine membrane is transformed into a COF membrane in the vapour phase of solvent and catalyst, along with the completion of crystallization process. Owing to the compact and highly crystalline structure, the resultant COF membranes exhibit an unprecedented permeance (water ≈ 403 L m−2 bar−1 h−1 and acetonitrile ≈ 519 L m−2 bar−1 h−1). Our two-step procedure via phase switching strategy can open up a new avenue to the fabrication of advanced organic crystalline microporous membranes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Membrane technology has been envisioned as the disruptive and essential technology to replace the current energy-intensive separation applications1,2,3,4,5. Exploring new materials and fabrication strategies for compact, highly ordered microporous membranes is a persistent pursuit6,7,8,9,10. Covalent organic frameworks (COFs) are a class of crystalline polymers with tunable and permanent pores, atomically ordered pore structures, and high porosity, constructed by the covalent linkage of organic building blocks (or monomers) based on reticular chemistry11,12,13,14. The diversity of organic building blocks endows COFs with exceptional structural designability, enabling the customization of the pore size and the functionality at molecular level15,16,17,18. For instance, choosing appropriate monomers, the COF pores can be manipulated to separate molecules based on size, shape, or charge19,20,21. Similarly, COFs with desired properties can be tailored through linkage modification or linkage transformation by taking advantage of their reversible nature22,23,24,25,26,27. These features make COFs potent materials for the fabrication of advanced membranes for selective molecular transport28.

COFs are mostly fabricated through a one-step procedure in liquid phase(s) by highly coupled polymerization and crystallization processes29. Majority of the reported COF membranes are assembled using this one-step procedure, predominantly in liquid phase using interfacial (oil–water biphasic system) or in-situ solvothermal (monophasic system) methods30. In liquids, controlling the concurrent polymerization and crystallization during membrane formation is quite challenging; primarily due to the high surface tension (2 × 10−2−5 × 10−2 N m−1)) and viscosity (0.3–4 cp) of liquids which makes the removal of by-product from the reaction site extremely difficult31,32. Consequently, the concentration of reacting monomers is low near the polymerization sites whereas that of byproducts is higher, leading to hindered reaction reversibility20,33,34. Moreover, the random movement of monomers/nanoparticles in liquid phase also leads to the formation of loose and low-crystallinity membranes22. Recently, we reported that eliminating liquids during the assembly of COF membranes such as at the solid–vapor interface could fabricate compact and highly crystalline membranes33. However, the dependence on the melting point of the vapor phase monomer dramatically restricts broad applicability. We envisaged that exploring a two-step procedure instead of one-step procedure to decouple the polymerization reaction process and the crystallization assembly process to the directed evolution of membrane structure, in hopes of achieving some breakthroughs in advanced COF membrane materials.

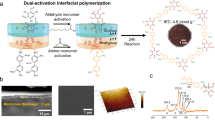

Herein, we report a two-step procedure to assemble COF membranes via a phase switching strategy. In the first step, i.e., the pre-assembly step, a mixed solution containing aldehyde and amine monomers was casted onto a support and underwent the polymerization process to obtain pristine membranes after solvent evaporation. In the assembly step, the pristine membranes underwent the crystallization process and were assembled into highly crystalline and compact COF membranes in the vapor phase of solvents and catalyst. The thickness of membranes was controlled to ≈150 nm. This phase switching strategy is validated by fabricating two kinds of COF membranes, which exhibit one of the highest permeance during nanofiltration separation.

Results

Fabrication and structural characterization of membranes

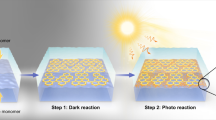

The fabrication of COF membranes in this work contains a pre-assembly step and an assembly step. As shown in Fig. 1a, monomers with different spatial configuration i.e., a C-2, 1,4-phenylenediamine (PDA), a C-3, 4,4′,4″-(1,3,5-triazine-2,4,6-triyl)trianiline (TTA) as amine monomers, and a C-3, 1,3,5-triformyl phloroglucinol (TFP) as aldehyde monomer, were chosen. In the first step, i.e., the pre-assembly step, a solution of mixed monomers (aldehyde and amine) was casted onto an Indium Tin Oxide (ITO) coated support to form a pristine polymeric solid membrane following evaporation of the solvent. The temperature was controlled at 60 °C to further exploit the reversibility of the imine linkages. In the second step, i.e., the assembly step, the pristine membrane was transformed into COF membrane in vapor phase containing solvents and catalyst at 145 °C through the linkage rearrangement. Free-standing COF membranes were obtained by etching the ITO layer. As shown in Fig. 2a, d, both COF membranes have high crystallinity as evidenced by the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern. The high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) images and selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns further confirm the high crystallinity of the membranes (Fig. 2b, e). The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images show defect-free surface with controllable thickness to ≈150 nm (Fig. 2c, f).

The membranes in this study are based on β-ketoenamine-linked Schiff base COFs, which are formed by the reactions which exhibit a meta-stable reversible state at low temperature and a more stable irreversible state at high temperature. The initial reversible Schiff base reaction yields an enol form leading to crystalline arrangement which is subsequently converted to keto–enol tautomer form. Moreover, these COFs exhibit excellent chemical stability under harsh acidic and basic conditions35,36, unlike the boronated COFs, which are highly sensitive to even small amount of moisture and thus difficult to be utilized in aqueous environments11. The pre-assembly step was delicately designed and carefully optimized in order to finally obtain highly crystalline and compact membranes in the assembly step and avoid the strong coupling between polymerization and crystallization. The properties of pristine membrane in the pre-assembly step have pronounced effect on the outcome of the COF membranes in the assembly step. In particular, the increase of solvent evaporation temperature in the pre-assembly step is unfavorable for the subsequent assembly step. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) of pristine membranes prepared at temperatures ranging from 35 to 140 °C was recorded (Fig. 3a). The pristine membranes fabricated at 35 and 50 °C still contains amine bands in the range of 3200–3400 cm−1. However, at 60 °C or above, no detectable amine bands were observed confirming the consumption of most of the monomers. Interestingly, it was found that the pristine membranes fabricated at 60 °C or below led to COF membranes with high crystallinity in the assembly step (Fig. 3b). In contrast, the pristine membranes fabricated at 80, 120, and 145 °C showed gradual decrease in crystallinity during the assembly step. We assume that at 60 °C, the pristine membranes are still in a reversible state, an important factor in obtaining high crystallinity in the assembly step. An increase in temperature during the pre-assembly step leads the reaction towards an irreversible state, leaving no freedom for linkage reversibility in the assembly step. Therefore, 60 °C at the pre-assembly step was proposed as the transition temperature between reversible and irreversible state.

a FT-IR of pristine membrane fabricated at various temperatures (35–145 °C). The disappearance of –NH2 bands between 3200 and 3400 cm−1 and the shift of C=O from 1643 to 1609 cm−1 has been shown in the insets. b XRD of COF membranes (assembled at 145 °C) from TFP–PDA pristine membranes pre-assembled at various temperatures.

The transformation from pristine membranes to COF membranes (exemplified by TFP–PDA) via phase switching was evaluated through FT-IR, XRD, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) analysis and SEM, shown in Fig. 4. FT-IR and XRD of TFP–TTA membranes have been shown in Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5. As shown in the FT-IR spectra, new stretching bands at 1248 and 1580 cm−1, corresponding to C=N and C=C, respectively, confirmed the formation of the β-ketoenamine linkage (Fig. 4a). The XRD pattern after 3 h exhibited a peak at a lower 2θ value of ≈4.7°, corrsponding to (100) reflection plane, the intensity of which gradually increased with time and reached its maximum value after 18 h of reaction. The second peak at a higher 2θ value of ≈26.9°, corresponding to (001) reflection plane, is attributed to π–π stacking between two layers (Fig. 4b). The slight deviation from the ideal crystal structure is consistent with the previous literatures37. The XPS data in Fig. 4c, d confirms that the linkages in pristine membranes are predominantly in the enol form, whereas the COF exists in β-ketoenamine form. As shown in Fig. 4e, the TFP–PDA pristine membrane has very low surface area and non-uniform pores. Comparatively, the TFP–PDA COF membrane has high surface area and narrow pore size distribution (Fig. 4f). It is noteworthy that the experimental pore size of the TFP–PDA COF membranes (1.4 nm) calculated from BET is slightly smaller than the theoretical pore size (1.7 nm). This experimental decrease in pore size might be due to the intergrowth of COF particles inside the pores during in-situ healing. The BET surface area and pore size of the TFP–TTA membranes are shown in Supplementary Fig. 6. The morphology of the membrane surface was observed through SEM during the transformation process. As shown in Fig. 4g, the pristine membrane is composed of a thread-like structure which transforms into a continuous and smooth morphology after 18 h of vapor treatment. The continuous growth of COF membranes indicates that dissolutions and recrystallizations of the COF seeds occurred by the emergence of large seeds due to the fusion of small seeds. These observations are consistent with other crystalline materials such as crystalline salts38,39, zeolites40,41,42, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)43,44, and COFs34. We also observed that thicker membranes were composed of a continuous membrane towards ITO surface, covered by large particles and threads. These particles and threads could be easily removed using adhesive tape before the etching step (Supplementary Figs. 1–3). By optimizing the monomers concentration, ultra-thin membranes were fabricated by avoiding the growth of particles completely.

The successful fabrication of two COF membranes by using monomers with different symmetries (C2 and C3) and different pore size using our two-step procedure demonstrates its genericity. For comparison, the pre-assembled membrane was treated in the liquid phase containing the same solvents and catalyst at 145 °C. The crystallinity of the as-fabricated membrane was much lower due to the low acidity of AcOH in liquid phase as it exists in the dimer state. Moreover, it was observed that the overall thickness of the membrane obtained in liquid phase was thicker than the membranes fabricated by phase switching due to the swelling effect of the liquid phase. However, following removal of the surface particles using adhesive tape, the phase switching membrane turned out to be more densely packed and thicker than membrane obtained in liquid phase (Supplementary Fig. 7). The reason for this can be ascribed to increased random and free movement of particles in the liquid phase, leading to their less dense assembly34,45. However, the pre-assembled particles in our work are confined in the solid phase, affording a more appropriate microenvironment for the assembly of a more densely packed membrane.

Performance evaluation of membranes

The performance of both membranes for nanofiltration was evaluated. As shown in Fig. 5a, the TFP–PDA COF membranes assembled at 145 °C after 18 h exhibited a water permeance of 403 ± 4 L m−2 h−1 bar−1 while the rejection rate of Congo red (CR) as a model dye was over 99%. The water permeance of TFP–PDA COF membranes assembled at 125, 135, and 155 °C was 513 ± 5, 444 ± 5, and 173 ± 9 L m−2 h−1 bar−1, respectively. The CR rejection increased from 78% to 99% when the temperature was increased from 125 to 155 °C (Supplementary Table 1). We propose that at 125 °C, the vapor pressure is not high enough to complete the crystallization process in 18 h, and although the permeance is high, the CR rejection is low due to the incomplete assembly. At 155 °C, the low flux may arise from the partial blockage of pores by intergrown COF particles, also reported in previous literatures45. Secondly, treatment at high temperature leads to kinetically stable product rapidly, but with poor orderliness. To confirm this, we characterized TFP–PDA membranes crystallized at 155 °C through XRD and BET. Indeed, the crystallinity and surface area of membranes crystallized at 155 °C is lower than those of membranes crystallized at 145 °C. We assume that growth of COF particles in the pores and low crystallinity at 155 °C render membranes low permeance (Supplementary Fig. 8). The fabrication conditions were further optimized by evaluating the membranes’ performance at a given time vs. temperature (Supplementary Table 1). The permeance of initial polymeric membranes is 800 ± 10 L m−2 h−1 bar−1 while the CR rejection rate is at 55 ± 4%. With the elapse of time, the permeance gradually decreased while the CR rejection rate increased. At the low temperature of 125 °C, the decrease in permeance and increase in CR rejection rate becomes slower. However, a sharp and abrupt trend is observed at high temperature (155 °C). At 12 h of reaction time at 155 °C, the permeance is similar to that of membranes obtained at 145 °C in 18 h, but the CR rejection is still at 82%. The reason for the low rejection may be the rapid assembly step at high temperature, resulting in some defects in the membranes46. Therefore, membranes fabricated at 145 °C in 18 h in the assembly step were chosen for the subsequent molecular transport performance evaluation. The performance evaluation of TFP–TTA membranes fabricated at various temperatures and at different time is given in Supplementary Table 2.

The TFP–PDA and TFP–TTA COF membranes exhibited high permeance for water and organic solvents (Fig. 5b); especially the TFP–PDA membrane exhibited water (403 ± 4 L m−2 h−1 bar−1) and acetonitrile (519.6 L m−2 h−1 bar−1) permeances. This permeance is among the highest ever reported for COF membranes (Supplementary Table 3). To further evaluate the effect of pore size (TFP–PDA = 1.4 nm, TFP–TTA = 1.09 nm), solutions containing different dyes (Alcian blue (AB), 1.25 × 2.22 nm; Congo red (CR), 0.73 × 2.56 nm; protoporphyrin IX (PPh-IX) 562 g/mol, 1.54 × 1.45 nm; methyl blue (MB) 1.74 × 2.36 nm; and orange G (OG) 0.85 × 1.1 nm) were chosen as model systems. Dyes can form aggregates in aqueous solution at high concentrations47,48, therefore, an ethanolic solution of PPH-IX was used to confirm the broad applicability of COF membranes for the dyes rejection1. As shown in Fig. 5c, both membranes exhibited excellent rejection rates for dyes larger than their corresponding pore size. The rejection rates of larger dyes such as AB, CR, PPH-IX, and MB remained more than 98% for both membranes. The difference in the rejection rates of the smaller dyes become more pronounced. The TFP–TTA membrane, with smaller pores, exhibited a rejection of 97.8% for OG compared with 79.3% by the TFP-PDA membrane.

Generally, 2D membranes such as of graphene oxide (GO) face the challenge of compactness at high pressure due to their layered structure49. Therefore, both membranes were subjected to a variety of pressures ranging from 0.5 to 3 bar. As shown in Fig. 5d, the permeance of both membranes remained unchanged at various pressures, confirming that the pores build the major routes for solvent transport. Similarly, long-term operation stability is a critical requirement for emerging membranes such as of COFs to compete with state-of-the-art nanofiltration membranes. Therefore, we tested both membranes in long-term operation. As shown in Fig. 5e, both membranes retained high permeance of water (93.7% by TFP–PDA and 96.6% by TFP–TTA) even after 96 h of operation. Similarly, reusability of membranes is another important requirement. The permeance and CR rejection rate of both membranes were evaluated after several cycles of operations (Fig. 5f). Each cycle included filtration of a CR aqueous solution for 30 min followed by filtration of distilled water and subsequent filtration of a CR solution. Due to its larger pore size, TFP–PDA membranes retained 93.4% of initial permeance and 100% of CR rejection while the TFP–TTA membrane retained 85.8% of the initial permeance after 36 cycles. The slight decline in permeance may be ascribed to the clogging of smaller pores by CR dye aggregation. Nevertheless, even after 96 h and 36 cycles of operation, the performance of both membranes was still much higher than the current state-of-the-art membranes.

The reliability of our two-step procedure via phase-switching was further confirmed by the fabrication of COF-LZU1 membranes with defect-free surface and high crystallinity as evident from the XRD data with characteristic peaks similar to the literature50. The completion of reaction was confirmed through FT-IR with the disappearance of peaks from the initial monomers and the formation of imine bonding (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Discussion

In summary, a phase switching strategy was proposed to assemble COF membranes. Unlike the common one-step procedure in liquid phase(s) with concurrent polymerization and crystallization, our two-step procedure of decoupling polymerization and crystallization by switching from liquid phase to vapor phase, can yield highly crystalline and more compact membranes. During the pre-assembly step, the pristine membranes were obtained in the liquid phase, while still at reversible state, which were then transformed into COF membranes in the assembly step in the vapor phase of catalyst and solvent by linkage rearrangement. The broad applicability of this phase switching strategy was confirmed by assembling three COF membranes with different geometries. Owing to the compact and highly crystalline structure, the COF membranes exhibited ultra-high separation performance, as well as superior long-term stability. Our two-step procedure and phase switching strategy may motivate further thinking in how to coordinate the chemical reaction process and the physical assembly process to acquire high-quality COF materials and many other organic crystalline microporous materials.

Methods

Pre-assembly step in liquid phase toward pristine membranes

TFP (2.10 mg, 0.01 mmol), 1,3,5-triformylbenzene (TFB, 1.62 mg, 0.01 mmol), PDA (1.62 mg, 0.015 mmol), TTA (3.54 mg, 0.01 mmol) were dissolved in separate vials in 1 ml DMAc each. Next, the mixed solution containing equal volume of TFP/PDA, TFP/TTA or TFB/PDA was poured on Indium tin oxide (ITO) coated disk; the solvents were evaporated at 60 °C to obtain pristine membranes.

Assembly step in vapor phase toward COF membranes

The pristine membranes from the pre-assembly step were placed on top of a glass bottle in a Teflon-lined autoclave. Solvents (oDCB, BuOH) and catalyst (AcOH) in a volumetric ratio of 1:1:0.1 (10 ml in total) were poured on bottom of the Teflon vessel, at least 5 cm below the membrane surface. The whole assembly was heated at 145 °C for 18 h to obtain COF membranes. Free-standing COF membranes were obtained by etching ITO layer through dilute HCl.

Solvothermal strategy

The pristine membrane from the pre-assembly step was also treated in the liquid phase containing oDCB, BuOH, and AcOH in a volumetric ratio of 1:1:0.1 (10 ml in total), and heated at 145 °C for 18 h. Free-standing COF membranes were obtained by etching ITO layer through dilute HCl.

Molecular transport experiments

A lab made dead-end filtration cell (active area of 4.1 cm2), equipped with magnetic stirrer and nitrogen flow for pressure maintenance, was used for molecular transport. DI water was used for water transport while reagent grade organic solvents were used for organic solvent nanofiltration experiments. All dyes except (PPH-IX) were dissolved in water for molecular separation. PPH-IX was dissolved in ethanol. The concentration of dyes ranged from 50 to 1000 ppm. The performance was evaluated at various cycles of operation. After each cycle, the membrane was washed with water and before next cycle. Equation (1) was used for the calculations of dye rejection:

cp and cf are the dyes concentration in permeate and feed solution, respectively.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data and detailed protocols that support the findings of this study are available within the main manuscript and Supplementary Information files. Additional data from the authors can be provided upon request. Source data are available.

References

He, X. et al. Controlling the selectivity of conjugated microporous polymer membrane for efficient organic solvent nanofiltration. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1900134 (2019).

Liang, B. et al. Microporous membranes comprising conjugated polymers with rigid backbones enable ultrafast organic-solvent nanofiltration. Nat. Chem. 10, 961–967 (2018).

Khan, N. A. et al. Structural characteristics and environmental applications of covalent organic frameworks. Energies 14, 2267 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Laminated self-standing covalent organic framework membrane with uniformly distributed subnanopores for ionic and molecular sieving. Nat. Commun. 11, 599 (2020).

Chen, X. L. et al. Ultra-selective molecular-sieving gas separation membranes enabled by multi-covalent-crosslinking of microporous polymer blends. Nat. Commun. 12, 6140 (2021).

Joshi, R. K. et al. Precise and ultrafast molecular sieving through graphene oxide membranes. Science 343, 752–754 (2014).

Karan, S., Jiang, Z. & Livingston, A. G. Sub-10 nm polyamide nanofilms with ultrafast solvent transport for molecular separation. Science 348, 1347–1351 (2015).

Peng, X., Jin, J., Nakamura, Y., Ohno, T. & Ichinose, I. Ultrafast permeation of water through protein-based membranes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 353–357 (2009).

Shi, Z. et al. Ultrafast separation of emulsified oil/water mixtures by ultrathin free-standing single-walled carbon nanotube network films. Adv. Mater. 25, 2422–2427 (2013).

Yang, Q. et al. Ultrathin graphene-based membrane with precise molecular sieving and ultrafast solvent permeation. Nat. Mater. 16, 1198 (2017).

Cote, A. P. et al. Porous, crystalline, covalent organic frameworks. Science 310, 1166–1170 (2005).

Ding, S.-Y. & Wang, W. Covalent organic frameworks (COFs): from design to applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 548–568 (2013).

Tan, C. et al. Recent advances in ultrathin two-dimensional nanomaterials. Chem. Rev. 117, 6225–6331 (2017).

He, C. et al. Microregulation of pore channels in covalent-organic frameworks used for the selective and efficient separation of ethane. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 52819–52825 (2020).

Yang, G. H., Zhang, Z., Yin, C. C., Shi, X. S. & Wang, Y. Polyamide membranes enabled by covalent organic framework nanofibers for efficient reverse osmosis. J. Polym. Sci. 1, 1–10 (2021).

Shi, X. et al. Flexible and robust three-dimensional covalent organic framework membranes for precise separations under extreme conditions. Nano Lett. 21, 8355–8362 (2021).

Li, K. et al. Controllable and rapid synthesis of conjugated microporous polymer membranes via interfacial polymerization for ultrafast molecular separation. Chem. Mater. 33, 7047–7056 (2021).

Liu, D. C. et al. Moderately crystalline azine-linked covalent organic framework membrane for ultrafast molecular sieving. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 37775–37784 (2021).

Yang, C. et al. High proton selectivity membrane based on the keto-linked cationic covalent organic framework for acid recovery. J. Membr. Sci. 640, 119800 (2021).

Fan, H., Gu, J., Meng, H., Knebel, A. & Caro, J. High-flux membranes based on the covalent organic framework cof-lzu1 for selective dye separation by nanofiltration. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 4083–4087 (2018).

Wang, H. et al. Recent progress in covalent organic framework thin films: fabrications, applications and perspectives. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 488–516 (2019).

Fan, C. et al. Scalable fabrication of crystalline cof membranes from amorphous polymeric membranes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 18051–18058 (2021).

Kong, W. et al. Amorphous-to-crystalline transformation toward controllable synthesis of fibrous covalent organic frameworks enabling promotion of proton transport. Chem. Commun. 55, 75–78 (2019).

Tan, J. et al. Manipulation of amorphous-to-crystalline transformation: towards the construction of covalent organic framework hybrid microspheres with NIR photothermal conversion ability. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 13979–13984 (2016).

Miao, Z. et al. Construction of covalent organic frameworks from nonporous covalent organic polymers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 4906–4910 (2019).

Ma, D.-L. et al. Transformation between 2D covalent organic frameworks with distinct pore hierarchy via exchange of building blocks with different symmetries. Chem. Commun. 56, 15418–15421 (2020).

Waller, P. J., AlFaraj, Y. S., Diercks, C. S., Jarenwattananon, N. N. & Yaghi, O. M. Conversion of imine to oxazole and thiazole linkages in covalent organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 9099–9103 (2018).

He, G., Zhang, R. & Jiang, Z. Engineering covalent crganic framework membranes. Acc. Mater. Res. 2, 630–643 (2021).

Zhang, P. C. et al. Covalent organic framework nanofluidic membrane as a platform for highly sensitive bionic thermosensation. Nat. Commun. 12, 1844 (2021).

Tao, S. S. et al. Confining H3PO4 network in covalent organic frameworks enables proton super flow. Nat. Commun. 11, 1981 (2020).

Peng, L. et al. Ultra-fast single-crystal polymerization of large-sized covalent organic frameworks. Nat. Commun. 12, 5077 (2021).

Gao, S. et al. The ionic liquid-H2O interface: a new platform for the synthesis of highly crystalline and molecular sieving covalent organic framework membranes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 36507–36516 (2021).

Khan, N. A. et al. Solid–vapor interface engineered covalent organic framework membranes for molecular separation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 13450–13458 (2020).

Dey, K. et al. Selective molecular separation by interfacially crystallized covalent organic framework thin films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 13083–13091 (2017).

Wang, L. et al. Activation of carbonyl oxygen sites in β-ketoenamine-linked covalent organic frameworks via cyano conjugation for efficient photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. small 17, 2101017 (2021).

Karak, S. et al. Constructing ultraporous covalent organic frameworks in seconds via an organic terracotta process. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 1856–1862 (2017).

Yang, J. et al. Protonated imine-linked covalent organic frameworks for photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 19797–19803 (2021).

Wang, X. F. et al. Particle dissolution and recrystallization progress of Al–Mg–Si–Cu alloy during solution treatment. Phys. Met. Metallogr. 121, 1258–1265 (2020).

Inoue, A., Utada, M. & Hatta, T. Halloysite-to-kaolinite transformation by dissolution and recrystallization during weathering of crystalline rocks. Clay Miner. 47, 373–390 (2012).

Wang, Y. R., Lin, M. & Tuel, A. Hollow TS-1 crystals formed via a dissolution-recrystallization process. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 102, 80–85 (2007).

Tao, H. X., Ren, J. W., Liu, X. H., Wang, Y. Q. & Lu, G. Z. Facile synthesis of hollow zeolite microspheres through dissolution-recrystallization procedure in the presence of organosilanes. J. Solid State Chem. 200, 179–188 (2013).

Tu, M., Wannapaiboon, S. & Fischer, R. A. Inter-conversion between zeolitic imidazolate frameworks: a dissolution-recrystallization process. J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 13710–13717 (2020).

Chen, X. et al. Temperature-responsive dissolution/recrystallization of Zn MOF enables the maximum efficiency and recyclability of catalysts. Chem. Commun. 56, 1960–1963 (2020).

Sun, Y. T., Ding, S., Xu, S. S., Duan, J. J. & Chen, S. Metallic two-dimensional metal-organic framework arrays for ultrafast water splitting. J. Power Sources 494, 229733 (2021).

Fan, H., Gu, J., Meng, H., Knebel, A. & Caro, J. High‐flux membranes based on the covalent organic framework COF‐LZU1 for selective dye separation by nanofiltration. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 4083–4087 (2018).

Kandambeth, S. et al. Selective molecular sieving in self-standing porous covalent-organic-framework membranes. Adv. Mater. 29, 1603945 (2017).

Coates, E. Aggregation of dyes in aqueous solutions. J. Soc. Dyers Colour 85, 355–368 (1969).

Navarro, A. & Sanz, F. Dye aggregation in solution: study of CI direct red I. Dye Pigment. 40, 131–139 (1999).

Zhang, W., Zhang, L., Zhao, H., Li, B. & Ma, H. A two-dimensional cationic covalent organic framework membrane for selective molecular sieving. J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 13331–13339 (2018).

Ding, S. -Y. et al. Construction of covalent organic framework for catalysis: Pd/COF-LZU1 in Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 19816–19822 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by Key Research and Development Program of Zhejiang Province, grant No. 2021C03173 (Z. J.), National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant No. 91934302 (Z. J.), 21961142013 (Z. J.), 22008172 (R. Z.), Research Fund for International Young Scientists funded by NSFC, grant No. 21850410457 (N. A. K.), Project funded by China Postdoctoral Science Foundation, grant No. 2020TQ0226 (R. Z.), 2021M692384 (R. Z.), and Program of Introducing Talents of Discipline to Universities, grant No. BP0618007 (Z. J.). We also thank the Haihe Laboratory of Sustainable Chemical Transformations for financial support. We acknowledge the help of Y. Chao during figures drawing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.A.K. designed the project and wrote the initial draft. Corresponding authors, i.e., R.Z., H.W., and Z.J. supervised the project. Z.J. mentored the project during its execution and revised the manuscript. X.W. and L.C. helped during the experiments. J.Y., M.L. performed some parts of the characterization. M.A.O. and C.S.A. gave their valuable theoretical suggestions. X.W. also simulated the XRD patterns of the COF membranes. All authors communicated actively during the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, N.A., Zhang, R., Wang, X. et al. Assembling covalent organic framework membranes via phase switching for ultrafast molecular transport. Nat Commun 13, 3169 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30647-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30647-3

This article is cited by

-

Research Progress in the Fabrication of Covalent Organic Framework Membranes for Chemical Separations

Chinese Journal of Polymer Science (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.