Abstract

Magnetic skyrmions are nanoscale spin textures touted as next-generation computing elements. When subjected to lateral currents, skyrmions move at considerable speeds. Their topological charge results in an additional transverse deflection known as the skyrmion Hall effect (SkHE). While promising, their dynamic phenomenology with current, skyrmion size, geometric effects and disorder remain to be established. Here we report on the ensemble dynamics of individual skyrmions forming dense arrays in Pt/Co/MgO wires by examining over 20,000 instances of motion across currents and fields. The skyrmion speed reaches 24 m/s in the plastic flow regime and is surprisingly robust to positional and size variations. Meanwhile, the SkHE saturates at ∼22∘, is substantially reshaped by the wire edge, and crucially increases weakly with skyrmion size. Particle model simulations suggest that the SkHE size dependence — contrary to analytical predictions — arises from the interplay of intrinsic and pinning-driven effects. These results establish a robust framework to harness SkHE and achieve high-throughput skyrmion motion in wire devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Magnetic skyrmions are nanoscale, topologically wound spin structures stabilized in a ferromagnetic background by competing magnetic interactions1,2. Their discovery at room temperature (RT) in chiral multilayer films comprising heavy metal-ferromagnet interfaces has sparked scientific and technological excitement3,4,5,6. Notably, the spin-orbit torque (SOT) generated at such interfaces by an in-plane charge current7,8 provides the ideal instrument for electrical manipulation of skyrmions5,9,10. Consequently, several device proposals seek to harness current-driven skyrmion motion within a wire, or ‘racetrack’ architecture11,12 towards applications in analog memory13, logic14, and synaptic computing15,16. In this light, achieving deterministic, efficient, and high-throughput skyrmion motion in wires is a critical challenge for the device community.

Initial demonstrations of skyrmion motion were extremely promising — showing efficient SOT manipulation10 and individual speeds of up to ~100 m/s5. However, progress since has been limited by significant challenges along three key fronts pertaining to the influence of intrinsic, extrinsic, and collective effects. First, in addition to the expected linear motion, an applied current also induces a traverse skyrmion deflection — known as the skyrmion Hall effect (SkHE) — which arises from the hydrodynamic Magnus force acting on the skyrmionic topological charge1,17,18,19. SkHE may enable defect avoidance20, however the transverse deflection — over 30∘ in some cases — may limit linear mobility18,21,22. While efforts to develop SkHE-free materials are underway23,24,25,26,27, several facets of SkHE remain unresolved amidst conflicting experimental results, e.g. the material-dependence of its magnitude, the existence of a saturation value, dependence on skyrmion size, etc.17,18,22,23,28. Next, skyrmion dynamics in sputtered multilayer wires may be affected on one hand by material granularity and defects29,30, and on the other by interactions with the wire edge31,32. However, these extrinsic effects are yet to be experimentally understood. Finally, high-throughput devices would require skyrmion motion at densities 10–100 times higher than prevailing experiments11, which have examined sparse configurations (< 1 μm−2).

Here we report on the ensemble dynamics of 80–200 nm-sized skyrmions forming dense (> 10 μm−2) arrays in Pt/Co/MgO multilayer wires. Using magnetic force microscopy (MFM) imaging, we examine over 20,000 instances of skyrmion motion over a range of applied currents and fields, spanning three distinct dynamic regimes: stochastic creep, deterministic creep and plastic flow. The onset of the deterministic motion is associated with finite SkHE, which grows and saturates at a moderate value (~22∘). While the velocity is found to be surprisingly robust to edge effects and skyrmion size variations, the SkHE is considerably reshaped in both cases. Our simulations suggest that the observed SkHE trend with skyrmion size — contrary to defect-free theoretical predictions — arises from the interplay of intrinsic and pinning-driven effects. Our results and insights establish a robust experimental framework to realize high-throughput skyrmion motion in wire devices for next-generation nanoelectronics.

Results

Imaging skyrmion dynamics

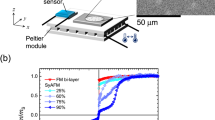

This work was performed at RT on [Pt(3)/Co(1.2)/MgO(1.5)]15 multilayer films sputtered on Si/SiO2 substrates and patterned into 2 μm wide wire devices (thickness in nm in parentheses, see Methods, SM1-2). The wires were connected through a circuit board to a pulse generator (Fig. 1a) to inject current pulses of fixed width (20 ns), varying magnitude and polarity, J = ±(1.0−5.8) × 1011 A/m2. The setup was mounted in an MFM with out-of-plane (OP) magnetic field (μ0H), enabling sequential in situ pulse injection and imaging of the wire (Fig. 1a, b). Pt/Co/MgO stacks are known to host Néel-textured skyrmions stabilized at RT by the interfacial Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction3,22. Following an established nucleation recipe (see Methods, SM3), skyrmion configurations were stabilized in the wires over a substantial field range — μ0H ~ 75–165 mT — as seen in MFM images (Fig. 1f: inset). The range of skyrmion densities (nS: 2–13 μm−2) and sizes (dS: 80–200 nm) achieved here (details in SM3) are vastly different from previous works5,17,18,21,22,23,28,30, and provide the variance required to establish statistical significance for our key claims.

a Schematic of the experimental setup. The [Pt(3)/Co(1.2)/MgO(1.5)]15 (thicknesses in nm in parentheses) was mounted onto the MFM setup with varying in situ out-of-plane (OP) magnetic fields (details in Methods). b Protocol used to inject current pulses (magnitude J = ±(1.0−5.8) × 1011 A/m2, width: 20 ns) into the device. Pulses of alternating polarity were applied sequentially, and the wire was imaged by in situ MFM before and after each pulse. c–e Representative MFM images (scalebar: 1 μm) acquired at OP magnetic fields μ0H = 105 mT before pulsing (c), after applying current pulses of J ≃ ∓ 5.7 × 1011 A/m2 (d, e). Bottom left (right) panel shows tracked positions of selected skyrmions identified by colored dots for −J (c, d) and +J (d, e) (details in SM4), whose motion is indicated by arrows. f Proportion, PM, of skyrmions in motion along the driving current direction plotted as a function of J for various OP fields. Insets show MFM images (scale bar: 500 nm) of the wire at varying μ0H (magnitudes in insets) following the skyrmion nucleation recipe (see Methods). Finite PM indicates the onset of deterministic skyrmion motion.

Current pulses of alternating polarity were applied sequentially to the wire (Fig. 1b) and the motion of individual skyrmions was quantified by tracking their positions from MFM images acquired before and after each pulse (Fig. 1c–e, details in SM4). Figure 1f summarizes the proportion of skyrmions, PM, moving along the current direction (J) for various fields. We expect PM to be positive for current-induced SOT displacement of left-handed Néel skyrmions stabilized in Pt/Co-based/MgO stacks3,5,33. For J < 4 × 1011 A/m2, PM remains below 5% — characteristic of stochastic motion due to current-induced thermal fluctuations30,34. As J is further increased, PM increases exponentially — reaching ~90% at J ≃ 5.8 × 1011 A/m2 — indicating a transition to driven skyrmion motion along the current direction. Finally, such deterministic motion can be further demarcated as creep or flow, which is discussed further below.

Skyrmion Hall effect

The polar plot in Fig. 2a summarizes the distribution of skyrmion dynamics across applied currents at a representative field (μ0H ≃ 75 mT). The variance in skyrmion velocity (vS) and angular deflection (θS) — both defined with respect to J (Fig. 2a: inset) — is expected due to the granularity inherent to metallic multilayers29,30. Nevertheless, it is established that adequate statistical sampling and controls can meaningfully describe the skyrmion dynamics phenomenology28,29. Correspondingly, Fig. 2b shows a plot of the averaged skyrmion velocity 〈vS〉 for each J. Notably, 〈vS〉 increases exponentially with J, reaching ~8 m/s for J ≃ 5.8 × 1011 A/m2, with some skyrmions moving at over 24 m/s. The velocities observed here are of the same order of magnitude as Co-based skyrmionic counterparts subjected to similar J5,21,22. Next, the threshold current for skyrmion motion increases with applied field, which can be ascribed to stronger pinning effects29,30. Importantly, however, the exponential trend of 〈vS〉(J) is field-independent, indicating its insensitivity to variations in nS for a given material system (c.f. Fig. 1f, see SM3). However, with increasing field, the viable range of currents is substantially reduced (e.g. J < 5.2 × 1011 A/m2 for μ0H ≃ 165 mT) due to the increased ease of skyrmion annihilation and stronger pinning5,30. Therefore, after demonstrating the consistency of skyrmion dynamics across fields (Figs. 1 and 2), the remainder of our work focuses — without loss of generality — on lower fields (75–105 mT) for statistically meaningful conclusions.

a Polar plot overview of the skyrmion motion statistics for μ0H ≃ 75 mT across all currents J (data for J < 0 flipped by 180∘), showing the spread of velocity (vS) and angular deflection (θS). The data is visibly biased towards the upper left quadrant. Inset shows a schematic defining vS and θS relative to the direction of J. b Plot of the average skyrmion speed, 〈vS〉, against J for various applied fields. Solid lines present exponential fits (see Methods), while shaded regions represent the standard deviation, also emphasized by error bars for selected points. The dotted line — determined from (d) — demarcates creep and plastic flow regimes. c 2D histogram color plot of skyrmion deflection, θS against vS for μ0H ≃ 75 mT across all currents. The data were binned by vS for this plot. Solid markers show the average deflection, 〈θS〉, for each vS bin. d Plot of 〈θS〉 against 〈vS〉 — determined as in (c) — for various applied fields. Solid lines present sigmoidal fits (see Methods), while shaded regions represent the standard deviation, also emphasized by error bars for selected points. Creep and plastic flow regimes are demarcated at \(\langle {\theta }_{{\rm{S}}}\rangle =0.5\ {\langle {\theta }_{{\rm{S}}}\rangle }^{{\rm{sat}}}\) using the fit.

Turning now to the angular deflection, skyrmion motion in Fig. 2a is noticeably skewed towards the upper left quadrant (θS > 0) — increasingly so at higher velocities. The observed deflection is consistent with the expected SkHE, as skyrmions with topological charge Q = +1 should possess a positive intrinsic Hall angle (θH > 0)1. The 2D histogram plot in Fig. 2c shows the variation of 〈θS〉 with 〈vS〉 across currents. For lower values of 〈vS〉 e.g. ≲6 m/s, 〈θS〉 is small and monotonically increasing while displaying a large variance. These attributes are characteristic of creep motion in a disordered background — wherein scattering from the large fraction of pinned skyrmions results in a wide spread in 〈θS〉19,28,30. As 〈vS〉 increases further, 〈θS〉 narrows in spread and grows in an S-curve fashion — eventually saturating at \({\theta }_{{\rm{S}}}^{\rm{sat}} \sim 2{2}^{\circ }\) for 〈vS〉 ≳ 12 m/s. The 〈θS〉 saturation signals the onset of plastic flow, wherein skyrmions move concomitantly (PM > 50%) in a weak pinning background19,22,28.

As shown in Fig. 2d, both the 〈θS〉(vS) profile and \({\theta }_{{\rm{S}}}^{\mathrm{sat}}\) magnitude are consistent over the entire field range (75–165 mT). This enables us to clearly demarcate the creep and plastic flow regimes in our work (Fig. 2d), which in turn establishes the current regime corresponding to plastic skyrmion flow (Fig. 2c: J ≥ 5.5 × 1011 A/m2). Such a demarcation, while contrasting with some reports that solely exhibit either creep18 or plastic flow28, is consistent with other works17,22,23. Surprisingly, the saturated magnitude of \({\theta }_{{\rm{S}}}^{\mathrm{sat}} \sim 2{2}^{\circ }\) is nearly 2–3 times lower than the 40–70∘ range found in most ferromagnetic multilayers17,18,22, and is comparable to the 25–35∘ values for ferrimagnetic systems23,25. Crucially, the established robustness with field enables us to examine extrinsic influences on the plastic flow of individual skyrmions in subsequent sections.

Effect of wire edge

Geometric confinement can strongly influence the stability and dynamics of skyrmions via magnetostatic and torque contributions9,13,35. Previous theoretical and experimental works on single skyrmion in the creep regime have studied their interaction with a geometric boundary or “edge”, and variously reported edge-induced skyrmion pinning17,36, annihilation31,36,37, expulsion13,32,37 or repulsion13,17,31. Here we examine the influence of confinement on the plastic flow of skyrmion arrays. Skyrmions in the plastic flow regime are binned by their individual distance x from the left edge of the wire, with 0 < x < 2 μm (see SM7). The binned skyrmion number NS(x) (Fig. 3c) is approximately uniform across the x-bins, with no evidence for preferential existence at the center or edge. Meanwhile Fig. 3a, b show a marked evolution in the dynamics with varying x-positions, which is quantified in Fig. 3d, e.

a, b Representative MFM images (scale bar: 1 μm) at μ0H ≃ 75 mT showing the forward (\(J\parallel +\hat{y}\)) (a) and reverse (\(J\parallel -\hat{y}\)) (b) plastic flow of skyrmions with varying distance x from the left edge. Overlaid dots correspond to initial skyrmion positions and lines show the extent of motion due to the current pulse. Insets define vS and θS with respect to J for both cases. c Binned histogram distribution of skyrmions based on their x-positions before motion. d, e Average velocity \(\left\langle {v}_{{\rm{S}}}(x)\right\rangle\) (d) and angular deflection \(\left\langle {\theta }_{{\rm{S}}}(x)\right\rangle\) (e) for skyrmions in each x-bin for forward (J∥+\(\hat{y}\), red) and reverse (J∥-\(\hat{y}\), blue) motion (details in SM7). Solid lines serve as guides-to-the-eye to indicate trends, while shaded regions represent the standard deviation, also emphasized by error bars for selected points.

Figure 3d shows that the binned velocity 〈vS(x)〉 remains consistently high (~8–10 m/s) across the wire width. A slight (~20%) decrease of 〈vS(x)〉 is found at the left edge of the wire — i.e. in the direction of skyrmion deflection. This suggests that skyrmion-edge interaction may have a measurable inelastic component — consistent with a dissipative process17,31. Meanwhile, the binned deflection 〈θS(x)〉 shows a parabolic evolution across the wire: increasing from ~−5∘ at the left to ~+25∘ at the center (c.f. Fig. 2d, \({\theta }_{{\rm{S}}}^{\mathrm{sat}} \sim 2{2}^{\circ }\)) and then dropping to ~+10∘ at the right. Crucially, we observe the same evolution of 〈vS(x)〉 and 〈θS(x)〉 when the motion is reversed (albeit with flipped sign: see Fig. 3d, e) and at higher fields (105 mT, see SM6). Noting the consistency of edge effects across field variations of 30 mT, we rule out the role of current-induced Oersted fields in the observed trends.

Instead, the 〈θS(x)〉 variation may be interpreted within the interplay of the intrinsic Hall effect of individual skyrmions with extrinsic effects from the wire edge and neighboring skyrmions. First, near the center (x ~ 1 μm), edge effects are negligible and neighboring skyrmion effects are compensated on both sides. Therefore, the ensuing 〈θS〉 is comparable to the saturation value (see Results: Skyrmion Hall effect). Next, at the left edge (x ~ 0 μm), the Magnus force is overcome by edge repulsion. The latter pushes the skyrmion back into the wire — resulting in a negative 〈θS〉. Finally, the gradual reduction of 〈θS〉 for (1 < x < 2 μm) cannot be explained by edge effects. Instead, it suggests that the gradual reduction of skyrmions on the right — whose transverse motion may repel the skyrmion of interest — may influence the magnitude of 〈θS〉 observed in our work. Finally, the robustness of these results to field and current direction underscores the deterministic role of extrinsic factors in shaping skyrmion dynamics in our wires.

Effect of skyrmion size

The size of a skyrmion determines its coupling to current-induced spin torques, and is therefore expected to influence its dynamics38,39. In Fig. 4, we examine the skyrmion size dependence seen in our experiments in the plastic flow regime for μ0H ≃ 75 mT and J over (5.5–5.8) × 1011 A/m2. The skyrmions are binned by their dS in MFM images (see SM7), which show a substantial spread over 80–200 nm (Fig. 4a insets, Fig. 4b). First, Fig. 4d shows that 〈vS〉 — while increasing as expected with J — is constant to ~10% across dS for fixed J. Such insensitivity of 〈vS〉 to dS, predicted for dS > 100 nm and recently reported for 〈dS〉 ~ 400 nm skyrmion bubbles28, may be ascribed to the onset of finite size effects within the skyrmion spin structure30.

a Representative cropped MFM image (scale bar: 1 μm) at μ0H ≃ 75 mT showing the evolution in plastic flow of skyrmions with varying size dS. The smallest 25% (red) and largest 25% (blue) of dS are highlighted. Overlaid dots correspond to initial skyrmion positions and lines show the extent of motion. Zoomed insets at top and bottom (scalebar: 100 nm) show selected small (top, < 110 nm) and large (bottom, >170 nm) skyrmions for comparison. b Binned histogram distribution of skyrmions, NS, based on their size, dS—which varies over 80–200 nm (details in SM7). c 2D histogram color plot of skyrmion deflection, θS against dS for μ0H = 75 mT across all currents in the plastic flow regime. The data were binned by dS and normalized in each bin for this plot. Solid markers show the average deflection, 〈θS〉, for each dS bin. Average velocity 〈vS〉 (d) and angular deflection 〈θS〉 (e) for skyrmions in each dS-bin for J over (5.5–5.8) × 1011 A/m2. Shaded regions represent the standard deviation, also emphasized by error bars for selected points.

Meanwhile, the variation of 〈θS〉 with dS across currents is shown in the 2D histogram plot in Fig. 4c. 〈θS〉 increases discernibly with dS across all J-values in the plastic flow regime (Fig. 4e) — from ~5–10∘ for dS ≲ 100 nm to ~20∘ for dS ~ 200 nm. While the limited current range for plastic flow (5.5–5.8 × 1011 A/m2) precludes meaningful J-dependent trends, the weakly increasing trend of 〈θS〉 with dS noted here is robust to binning (SM7). Moreover, similar results are observed for 105 mT (SM6, 7), and another wire device as well (SM6). Our results contrast strongly with the 1/dS dependence of θH expected theoretically from the Thiele model for rigid skyrmions38,40, and with experimental reports of such a 〈θS〉 trend in the creep regime18. Meanwhile, a recent work has reported dS-independent 〈θS〉 in the plastic flow regime28. In light of contrasting theoretical and experimental reports, the size dependence of SkHE has increasingly assumed importance. Our simulations and theoretical work attempt to identify plausible origins of these discrepancies.

Micromagnetics

Micromagnetic simulations were performed for a grain-free environment using stack parameters consistent with experiments to study the size dependence of the intrinsic SkHE (see Methods, SM8)41. Skyrmions were stabilized in a 2 × 4 μm wire geometry with varying μ0H (84–93 mT, see e.g. Fig. 5a, b), which resulted in a 20% variation in simulated dS over 129–164 nm. Analysis of the current-induced skyrmion motion, shown in Fig. 5c, d for J = 9.5 × 1011 A/m2, reveals that with increasing \({d}_{{\rm{S}}}^{{\rm{m}}}\), the simulated \(\langle {v}_{{\rm{S}}}^{{\rm{m}}}\rangle\) initially increases and eventually saturates for dS ≳ 150 nm. Meanwhile \(\langle {\theta }_{{\rm{S}}}^{{\rm{m}}}\rangle\) decreases from 40∘ to 20∘. Both these trends are consistent with the expected rigid skyrmion behavior and with recent simulations in the creep regime18,30. However, neither our grain-free micromagnetic simulations nor those incorporating inhomogeneity22,29,30 can explain the dS-dependent \(\langle {\theta }_{{\rm{S}}}^{\rm{m}}\rangle\) trends in the plastic flow regime seen in Fig. 4, or in other recent works28. Therefore, we turn to the particle model — an established technique for elucidating the dynamics of skyrmion arrays in a disordered background (see Methods)19,42.

a, b Representative micromagnetic magnetization of a 2 × 4 μm2 wire showing a single skyrmion formed upon relaxation at μ0H ≃ 85 mT. The grain-free simulations were performed using stack parameters consistent with experiments (details in Methods). c, d Evolution of micromagnetic simulated average velocity \(\langle {v}_{{\rm{S}}}^{{\rm{m}}}\rangle\) (c) and average angular deflection \(\langle {\theta }_{{\rm{S}}}^{{\rm{m}}}\rangle\) (d) with dS — extracted from a series of such simulations at a representative J = 9.5 × 1011 A/m2. Solid lines represent sigmoidal (c) and linear (d) fits, respectively.

Particle model

As shown in Fig. 6a, b, skyrmions are represented as an array of point particles, while the disorder is modeled using pinning sites of radius, Rpin (details in Methods). Within this model, the effectiveness of pinning scales with the area coverage, given by \({({d}_{{\rm{S}}})}^{2}/{({R}_{{\rm{pin}}})}^{2}\), where dS is the skyrmion size. Therefore, the impact of changing skyrmion size can be modeled either by increasing/decreasing dS or by increasing/decreasing 1/Rpin. Here, we increase Rpin to emulate the effect of reducing dS (Fig. 6a), wherein smaller skyrmions would experience a larger interaction landscape with a given pinning site. The \({\rm{d}}_{{\rm{S}}}^{{\rm{P}}}\) in Fig. 6c, d is described as a dimensionless number based on the ratio of the dS to Rpin. The simulations were seeded with 1500 particles and 1200 pinning sites, and the system was subjected to a fixed drive corresponding to plastic flow under the modified Thiele equation (see Methods). The intrinsic, or pin-free skyrmion Hall angle, θH, was set to 37∘, while Rpin was varied over a wide range to simulate the role of pinning effects in the observed size dependence of skyrmion dynamics.

a, b Schematics of particle model simulations (details in Methods) which examine the dynamics of point-like skyrmion particles (foreground, red) in the presence of pinning sites with radius Rpin (background, blue). Black lines show representative trajectories of skyrmions. Decreasing Rpin within the model (left to right) emulates the effect of increasing dS. c, d Evolution of particle model simulated average velocity \(\langle {v}_{{\rm{S}}}^{{\rm{p}}}\rangle\) (c) and average angular deflection \(\langle {\theta }_{{\rm{S}}}^{{\rm{p}}}\rangle\) (d) with 1/Rpin ≡ dS extracted from a series of particle model simulations with fixed drive.

On one hand, Fig. 6d shows that the particle model angular deflection, \(\langle {\theta }_{{\rm{S}}}^{{\rm{p}}}\rangle\) decreases monotonically with reducing dS (simulated by increasing Rpin) to values substantially below the intrinsic Hall angle (θH = 37∘). Additional simulations for θH = 45∘ confirm this trend, which is qualitatively consistent with experiments. The simulations suggest that while smaller skyrmions may in fact have a higher intrinsic θH, as per the Thiele model38,40, extrinsic interactions may considerably reshape the effective \(\langle {\theta }_{{\rm{S}}}^{{\rm{p}}}\rangle\). In particular, the stronger influence of pinning on smaller skyrmions may impede their transverse deflection, reducing \(\langle {\theta }_{{\rm{S}}}^{{\rm{p}}}\rangle\) to well below the intrinsic value. Meanwhile the simulation results also suggest the dS-independent SkHE reported in another recent work28 may result from the dominance of pinning effects over the intrinsic Hall effect. In this case, the effective pinning could be acting at scales much larger than dS, and could therefore result in the diminished contribution of variations in dS. On the other hand, Fig. 6c shows that the particle model velocity, \(\langle {v}_{{\rm{S}}}^{{\rm{p}}}\rangle\) increases linearly with 1/Rpin ≡ dS, likely because increased pinning would slow down point-like skyrmions. In comparison, the dS-independence of vS in our experiments and previous work28 may be attributed, from micromagnetic simulations, to the onset of bubble-like internal structure of skyrmions30. Such textural size effects, whose internal modes may, for smaller dS, also reduce the effective magnitude of adiabatic and non-adiabatic damping, are beyond the scope of these particle model simulations. Future theoretical works may incorporate these effects and consider the skyrmion interactions arising from the vastly higher magnitude of skyrmion densities in our experiments. Nevertheless, these insights provide an important stepping stone for delineating intrinsic and extrinsic contributions to skyrmion dynamics.

Discussion

In summary, we have presented a systematic study of the ensemble dynamics of skyrmions forming dense array configurations in multilayer wire devices. With increasing current, we observe distinct transitions in skyrmion dynamics — from stochastic to deterministic creep, accompanied by SkHE onset, and then to plastic flow — wherein SkHE saturates at ~22∘. Within the plastic flow regime, we find that the skyrmion velocity is surprisingly robust to edge effects and skyrmion size, while the SkHE varies considerably in response to both. Notably, the weak increase of SkHE with skyrmion size contradicts existing predictions for isolated, rigid skyrmions. Instead, we conclude that the intrinsic Hall effect of skyrmions is strongly reshaped by extrinsic contributions in our wires — including geometric confinement, disorder-induced pinning effects and skyrmion-skyrmion interactions.

The insights from our work dispel several prevailing notions on skyrmion dynamics in multilayers, and pave imminent materials and device directions for high-throughput racetrack devices. First, the relatively small magnitude of SkHE in our case (saturated, ~22∘) is comparable to ferrimagnetic multilayers23. This suggests that materials design efforts for optimizing SkHE should continue exploring conventional ferromagnets in addition to newer compensated systems. Second, we find the skyrmion-edge interaction to be weakly inelastic: unlike several predictions32,36,37, the edge does not annihilate or pin skyrmions. In fact, such skyrmion-edge interactions may be exploited to channel skyrmion motion within suitably designed device geometries14. Third, size effects on skyrmion dynamics are reshaped by material granularity and skyrmion-skyrmion interactions. Contrary to defect-free theoretical predictions, in our case smaller skyrmions move equally fast, and importantly with reduced SkHE. While emphasizing accurate inclusion of these effects in future theoretical works, we postulate that they may serve as tuning parameters to achieve bespoke size-dependent skyrmion dynamics in racetrack devices43,44. Finally, we note that the striking individuality of our skyrmions within dense, disordered arrays bodes well for their use as stochastic spiking neurons in synaptic computing applications15,16.

Methods

Film deposition

Multilayer stacks of Ta(3)/[Pt(3)/Co(1.2)/MgO(1.5)]15/Ta(4) (nominal layer thicknesses in nm in parentheses) were deposited on pre-cleaned thermally oxidized 200 mm Si wafers by ultrahigh vacuum magnetron sputtering at RT using the Singulus TimarisTM system. Magnetization measurements were performed on the film using the MicroSenseTM Model EZ11 vibrating sample magnetometer. An effective OP anisotropy, Keff of 0.17 MJ/m3 and saturation magnetization, Ms of 1.1 MA/m were determined from the M(H) data. The DMI, D and exchange stiffness, A of the film were determined to be 1.6 mJ/m2 and 24 pJ/m, respectively, using established techniques4,5,6. These values are in line with published results on Pt/Co(0.9)/MgO stacks3,22.

Device fabrication

A 300 nm thick negative resist, Ma-N 2403, was spin-coated on the multilayer film. Wires of dimensions 2 × 10 μm were exposed using the ElionixTM electron beam lithography tool. The patterns were transferred onto the multilayer film using an Oxford CAIBETM ion beam etching system, and residual resist was lifted off in an ultrasonic bath. Top electrodes were subsequently patterned using an EVGTM optical mask aligner, followed by the deposition of the electrode stack Ta(5)/Au(100)/Ru(20) using the ChironTM UHV magnetron sputtering system.

MFM and electrical pulsing setup

MFM imaging was performed using a Veeco DimensionTM 3100 scanning probe microscope with Co-alloy coated SSS-MFMRTM tips. The sharp tip profile (diameter ~30 nm), ultra-low moment (~80 emu/cm3), and lift heights of 20–30 nm used during scanning provided high-resolution MFM images while introducing minimal stray field perturbations. Our earlier works have established MFM as a reliable tool for imaging sub-100 nm skyrmions in multilayer films6,45. In situ electrical pulsing and imaging were carried out in our custom-designed platform consisting of a TektronixTM AFG3252 pulse generator, SRSTM SIM954 inverting amplifier, TektronixTM TDS 7404 oscilloscope and the microscope. The device under test was wire-bonded to the chip carrier and subsequently mounted onto the MFM setup with varying in situ OP magnetic fields of 75–165 mT, following ex situ negative OP saturation. The device was impedance matched and found to be ~50 Ω. Ambipolar pulses of amplitude 1–3.7 V were injected, corresponding to current densities of (1.0–5.8) × 1011 A/m2 assuming a total metallic layer thickness of 63 nm. Short pulse duration of 20 ns was used to limit Joule heating effects on skyrmion nucleation, deletion and motion. The resistance and zero field configuration of the devices were verified prior to and after electrical pulsing, affirming that the pristine device form was preserved over the course of electrical pulse injection experiments.

Electrical pulsing experiments

Magnetic configurations consisting solely of skyrmions were stabilized over these fields by injecting bipolar current pulses of magnitude J < 5.5 × 1011 A/m2 (details in SM3). The procedure was repeated until all stripes were broken up into skyrmions, and no further skyrmions could be created. Subsequently, current-driven skyrmion dynamics experiments were performed with J ranging over (1.0–5.8) × 1011 A/m2. Skyrmion motion was analysed by identifying and tracking the skyrmion positions on the MFM image after each pulse. The 〈vS〉 and 〈θS〉 were extracted by calculating their average displacement over an effective pulse duration of 20 ns, taking into account the rise and fall times. The 〈vS〉 vs J (Fig. 2b) and 〈θS〉 vs 〈vS〉 (Fig. 2d) plots are fitted using the exponential (1) and sigmoidal (2) functions respectively, defined as

where a, b, c and d are constants.

Skyrmion dynamics analysis

To ensure that the devices imaged after pulsing were at identical positions for reliable tracking and analysis of skyrmion motion, an image registration protocol established using the image processing toolbox in MATLAB® was implemented. The MFM images obtained from the consecutive pulses were aligned by performing a 2D geometric transformation consisting of translation, rotation and shear relative to a reference image (described in SM4). Following image alignment, all skyrmions were identified and each was tagged with a unique marker. Next, each skyrmion was traced to its new position after pulsing from its original position by systematically tracking around its nearest position starting from top-down (or bottom-up, depending on the pulse direction). The rigorous tracking protocol accounts for nearly all skyrmion motion, as the local skyrmion number is typically unchanged through the pulsing experiments (see SM4).

Micromagnetic simulations

Micromagnetic simulations were performed using the MuMax3 software41 on a rectangular area of 2 × 4 μm2 to mimic the experimental wire structure. In view of computational constraints, the 15 repeat stack was simulated with an effective medium model5, wherein each repeat was represented by one effective FM layer. The magnetic parameters used in the effective medium model were rescaled from the experimentally measured magnetic parameters, where A = 5.05 pJ/m, Ms = 0.23 MA/m, Keff = 0.070 MJ/m3 and D = 0.37 mJ/m2 5. An experimentally determined Gilbert damping parameter of α = 0.05 was used in this simulation (details in SM1). To simulate the skyrmion dynamics, the SOT on the Co layer was modeled as an anti-damping-like torque from the adjacent Pt layer with an effective spin-Hall angle of 0.1. For simplicity, field-like torque originating from Pt was not considered and simulations were carried out at zero-temperature. Additionally, the role of thermal heating was neglected in line with experimental observation of negligible current-induced heating effects (see SM3).

Particle model simulations

Skyrmion dynamics within the particle model was simulated using a modified Thiele equation19,42

Here, αd is the damping and αm is the Magnus force. The term \({F}_{i}^{{\rm{ss}}}\) is the skyrmion repulsive interaction, and \({F}_{i}^{{\rm{sp}}}\) is the skyrmion-pinning interaction. The pinning was modeled as arising from localized sites of radius Rpin with a finite range harmonic attractive potential which gives a maximum pinning force strength of Fpin. The term FD represents a dc drive on the skyrmions applied in the x-direction. The skyrmion velocity parallel and perpendicular to the drive is \({v}_{{\rm{S}},\parallel }^{{\rm{P}}}\) and \({v}_{{\rm{S}},\perp }^{{\rm{P}}}\) respectively, while the measured skyrmion Hall angle is \({\theta }_{S}^{{\rm{P}}}={\tan }^{-1}({v}_{{\rm{S}},\perp }^{{\rm{P}}}/{v}_{{\rm{S}},\parallel }^{{\rm{P}}})\). In the absence of disorder, the skyrmion Hall angle is \({\tan }^{-1}({\alpha }_{{\rm{m}}}/{\alpha }_{{\rm{d}}})\). The simulations presented here were performed with the ratio of the number of pinning sites to the number of skyrmions being 0.6. To mimic the effect of changing the skyrmion diameter, the pinning force was held constant, and the pinning radius Rpin was varied. In this case, a large pinning site would correspond to a smaller skyrmion. The effective skyrmion Hall angle and the skyrmion velocity were then measured from the simulations. The values of Fpin = 1.0, αd = 1.34, and αm = 1.0 were used for simulations, giving an intrinsic Hall angle of 37∘.

Data availability

The data generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author(s) on reasonable request.

References

Nagaosa, N. & Tokura, Y. Topological properties and dynamics of magnetic skyrmions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 899–911 (2013).

Wiesendanger, R. Nanoscale magnetic skyrmions in metallic films and multilayers: a new twist for spintronics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16044 (2016).

Boulle, O. et al. Room-temperature chiral magnetic skyrmions in ultrathin magnetic nanostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 449–454 (2016).

Moreau-Luchaire, C. et al. Additive interfacial chiral interaction in multilayers for stabilization of small individual skyrmions at room temperature. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 444–448 (2016).

Woo, S. et al. Observation of room-temperature magnetic skyrmions and their current-driven dynamics in ultrathin metallic ferromagnets. Nat. Mater. 15, 501–506 (2016).

Soumyanarayanan, A. et al. Tunable room temperature magnetic skyrmions in Ir/Fe/Co/Pt multilayers. Nat. Mater. 16, 898–904 (2017).

Miron, I. M. et al. Current-driven spin torque induced by the Rashba effect in a ferromagnetic metal layer. Nat. Mater. 9, 230–234 (2010).

Miron, I. M. et al. Perpendicular switching of a single ferromagnetic layer induced by in-plane current injection. Nature 476, 189–193 (2011).

Sampaio, J., Cros, V., Rohart, S., Thiaville, A. & Fert, A. Nucleation, stability and current-induced motion of isolated magnetic skyrmions in nanostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 839–844 (2013).

Jiang, W. et al. Blowing magnetic skyrmion bubbles. Science 349, 283–286 (2015).

Parkin, S. S. P., Hayashi, M. & Thomas, L. Magnetic domain-wall racetrack memory. Science 320, 190–194 (2008).

Fert, A., Reyren, N. & Cros, V. Magnetic skyrmions: advances in physics and potential applications. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 17031 (2017).

Tomasello, R. et al. A strategy for the design of skyrmion racetrack memories. Sci. Rep. 4, 6784 (2014).

Luo, S. et al. Reconfigurable Skyrmion Logic Gates. Nano Lett. 18, 1180–1184 (2018).

Li, S. et al. Magnetic skyrmion-based artificial neuron device. Nanotechnology 28, 31LT01 (2017).

Pinna, D. et al. Skyrmion gas manipulation for probabilistic computing. Phys. Rev. Appl. 9, 064018 (2018).

Jiang, W. et al. Direct observation of the skyrmion Hall effect. Nat. Phys. 13, 162–169 (2016).

Litzius, K. et al. Skyrmion Hall effect revealed by direct time-resolved X-ray microscopy. Nat. Phys. 13, 170–175 (2016).

Reichhardt, C. & Olson Reichhardt, C. J. Noise fluctuations and drive dependence of the skyrmion Hall effect in disordered systems. N. J. Phys. 18, 095005 (2016).

Iwasaki, J., Mochizuki, M. & Nagaosa, N. Universal current-velocity relation of skyrmion motion in chiral magnets. Nat. Commun. 4, 1463 (2013).

Hrabec, A. et al. Current-induced skyrmion generation and dynamics in symmetric bilayers. Nat. Commun. 8, 15765 (2017).

Juge, R. et al. Current-driven skyrmion dynamics and drive-dependent skyrmion Hall effect in an ultrathin film. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 044007 (2019).

Woo, S. et al. Current-driven dynamics and inhibition of the skyrmion Hall effect of ferrimagnetic skyrmions in GdFeCo films. Nat. Commun. 9, 959 (2018).

Dohi, T., DuttaGupta, S., Fukami, S. & Ohno, H. Formation and current-induced motion of synthetic antiferromagnetic skyrmion bubbles. Nat. Commun. 10, 5153 (2019).

Hirata, Y. et al. Vanishing skyrmion Hall effect at the angular momentum compensation temperature of a ferrimagnet. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 232–236 (2019).

Zhang, X., Zhou, Y. & Ezawa, M. Antiferromagnetic skyrmion: stability, creation and manipulation. Sci. Rep. 6, 24795 (2016).

Zhang, X., Zhou, Y. & Ezawa, M. Magnetic bilayer-skyrmions without skyrmion Hall effect. Nat. Commun. 7, 10293 (2016).

Zeissler, K. et al. Diameter-independent skyrmion Hall angle observed in chiral magnetic multilayers. Nat. Commun. 11, 428 (2020).

Kim, J.-V. & Yoo, M.-W. Current-driven skyrmion dynamics in disordered films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 110, 132404 (2017).

Legrand, W. et al. Room-temperature current-induced generation and motion of sub-100 nm skyrmions. Nano Lett. 17, 2703–2712 (2017).

Iwasaki, J., Mochizuki, M. & Nagaosa, N. Current-induced skyrmion dynamics in constricted geometries. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 742–747 (2013).

Yoo, M.-W., Cros, V. & Kim, J.-V. Current-driven skyrmion expulsion from magnetic nanostrips. Phys. Rev. B 95, 184423 (2017).

Woo, S. et al. Spin-orbit torque-driven skyrmion dynamics revealed by time-resolved X-ray microscopy. Nat. Commun. 8, 15573 (2017).

Emori, S., Umachi, C. K., Bono, D. C. & Beach, G. S. Generalized analysis of thermally activated domain-wall motion in Co/Pt multilayers. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 378, 98–106 (2015).

Du, H. et al. Edge-mediated skyrmion chain and its collective dynamics in a confined geometry. Nat. Commun. 6, 8504 (2015).

Lai, P. et al. An improved racetrack structure for transporting a skyrmion. Sci. Rep. 7, 45330 (2017).

Bessarab, P. F. et al. Lifetime of racetrack skyrmions. Sci. Rep. 8, 3433 (2018).

Thiele, A. A. Steady-state motion of magnetic domains. Phys. Rev. Lett. 30, 230–233 (1973).

Locatelli, N., Cros, V. & Grollier, J. Spin-torque building blocks. Nat. Mater. 13, 11–20 (2013).

Knoester, M. E., Sinova, J. & Duine, R. A. Phenomenology of current-skyrmion interactions in thin films with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 89, 064425 (2014).

Vansteenkiste, A. et al. The design and verification of MuMax3. AIP Adv. 4, 107133 (2014).

Reichhardt, C., Ray, D. & Reichhardt, C. J. O. Collective transport properties of driven skyrmions with random disorder. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 217202 (2015).

Parkin, S. & Yang, S.-H. Memory on the racetrack. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 195–198 (2015).

Zhao, W. S. et al. Magnetic domain-wall racetrack memory for high density and fast data storage. In 11th International Conference on Solid-State and Integrated Circuit Technology, 1–4 https://doi.org/10.1109/ICSICT.2012.6466687 (IEEE, 2012).

Ho, P. et al. Geometrically tailored skyrmions at zero magnetic field in multilayered nanostructures. Phys. Rev. Appl. 11, 024064 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank Qi Jia Yap, Sze Ter Lim, and Franck Ernult for valuable experimental inputs, and Soong-Geun Je, Mi-Young Im, and Xichao Zhang for insightful discussions. We acknowledge the support of the National Supercomputing Centre (NSCC) for computational resources. This work was supported by the SpOT-LITE programme (Grant Nos. A1818g0042, A18A6b0057), funded by Singapore’s RIE2020 initiatives, and by the Pharos Skyrmion programme (Grant No. 1527400026) funded by A*STAR, Singapore. Further, we gratefully acknowledge the support of the U.S. Department of Energy through the LANL/LDRD program for this work. This work was also supported by the US Department of Energy through the Los Alamos National Laboratory. Los Alamos National Laboratory is operated by Triad National Security, LLC, for the National Nuclear Security Administration of the U. S. Department of Energy (Contract No. 892333218NCA000001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K.C.T., P.H., and A.S. designed and initiated the research. A.K.C.T. and J.L. designed the in situ device imaging setup. P.H. and L.S.H. fabricated the devices. H.K.T. conducted magnetometry measurements, while J.L. carried out the damping measurements. A.K.C.T. carried out the MFM experiments and analyzed the imaging data. J.L. performed the micromagnetic simulations and analyzed the data with A.K.C.T. and P.H. C.J.O.R. and C.R. performed and analyzed the particle model simulations. P.H. and A.S. coordinated and supervised the project. All authors discussed the results and provided inputs to the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Shunsuke Fukami, Olga Kazakova and Yan Zhou for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tan, A.K.C., Ho, P., Lourembam, J. et al. Visualizing the strongly reshaped skyrmion Hall effect in multilayer wire devices. Nat Commun 12, 4252 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24114-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24114-8

This article is cited by

-

All-electrical skyrmionic magnetic tunnel junction

Nature (2024)

-

Skyrmion pinning energetics in thin film systems

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Collective skyrmion motion under the influence of an additional interfacial spin-transfer torque

Scientific Reports (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.