Abstract

Layered Li-rich transition metal oxides undergo O-redox, involving the oxidation of the O2− ions charge compensated by extraction of Li+ ions. Recent results have shown that for 3d transition metal oxides the oxidized O2− forms molecular O2 trapped in the bulk particles. Other forms of oxidised O2− such as O22− or (O–O)n− with long bonds have been proposed, based especially on work on 4 and 5d transition metal oxides, where TM–O bonding is more covalent. Here, we show, using high resolution RIXS that molecular O2 is formed in the bulk particles on O2‒ oxidation in the archetypal Li-rich ruthenates and iridate compounds, Li2RuO3, Li2Ru0.5Sn0.5O3 and Li2Ir0.5Sn0.5O3. The results indicate that O-redox occurs across 3, 4, and 5d transition metal oxides, forming O2, i.e. the greater covalency of the 4d and 5d compounds still favours O2. RIXS and XAS data for Li2IrO3 are consistent with a charge compensation mechanism associated primarily with Ir redox up to and beyond the 5+ oxidation state, with no evidence of O–O dimerization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Layered Li-rich 3d transition metal oxide intercalation compounds, such as Li[Li0.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54]O2, have received a great deal of attention because Li+ can be extracted beyond the limit of transition metal (TM) oxidation, with the charge being compensated by oxidation of the O2‒ ions (O-redox)1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. These compounds typically possess honeycomb ordered Li and TM within the TM layer. However, Mn-based honeycomb ordered structures do not provide a stable framework for oxidised O2− and have been shown to undergo extensive TM migration, and bulk O–O dimerization leading to voltage hysteresis and loss of energy density, in addition to surface O2 evolution10,11,12,13,14. It has been shown recently that the dimerised O–O is molecular O2, which is trapped in voids within the bulk of the charged particles15,16. Molecular O2 formation is responsible for both surface O-loss and bulk O-redox.

Pioneering work by Tarascon, Doublet and co-workers17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 and by others26,27,28,29,30,31, on the 4d- and 5d-based analogues of the 3d compounds, such as Li2RuO3, Na2RuO3, Li2Ru0.5Mn0.5O3, Li2IrO3 and Li2Ir0.75Sn0.25O3, has led to important advances in the understanding of O-redox. These systems possess the same honeycomb ordered Li and TM ions within the TM layer. With the exception of Li2IrO3, they exhibit voltage hysteresis, with a plateau on charge and a low voltage S-shaped profile on subsequent discharge. Loss of honeycomb ordering due to Li/TM disordering accompanies the voltage hysteresis along with O2 loss from the surface of the particles17,19,21,26,29. It has been reported that peroxides O22− and longer O–O dimers form beyond the limits of transition metal oxidation in the 4 and 5d transition metal oxides17,19. The more strongly hybridised TM–O bonding of the 4 and 5d transition metals compared with the 3d counterparts has been cited as a reason for stabilising such O–O species with longer O–O bonds18,19,20,32. In highly covalent transition metal sulphides, selenides and tellurides, electron holes can be stabilised through dimerization of the chalcogen (S2)2− which remains coordinated to the transition metal due to the strong orbital overlap33.

It has proved very challenging to identify experimentally the form of oxidised O2− in charged materials. The recent application of high resolution RIXS spectroscopy has proved useful in probing the nature of oxidised O2−15,16. Here we apply this technique to the 4 and 5d materials, providing direct evidence for the presence of molecular O2, trapped in the bulk of the archetypal 4d and 5d systems Li2RuO3, Li2Ru0.5Sn0.5O3 and Li2Ir0.5Sn0.5O3. The O2 is formed only through charging across the high voltage plateau and is reduced on subsequent discharge, in line with our findings for Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2, disordered rocksalt Li2MnO2F and the P2-type Na-ion cathodes15,16,34. We find no evidence of molecular O2 formation or other O–O dimers in Li2IrO3 up to the limits of oxidation and instead identify stable electron holes formed in bonding TM–O orbitals, consistent with previous reports indicating reversible Ir5+ to Ir5.5+ oxidation instead of O oxidation and reinforcing the link between bulk O2 formation and the loss of high voltage plateau26. These data indicate that the more covalent TM–O bonding in 4 and 5d compared with 3d TM oxides still favours the formation of molecular O2, helping to explain why O-loss is also observed from the surface of these compounds. The implication is that the O-redox process, involving molecular O2 formation at the surface and in the bulk, is the same for Li-rich systems with the honeycomb superstructure moving down the Periodic Table.

Results

The Li-rich ruthenates and iridates

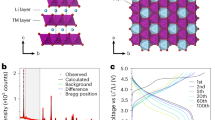

Li2RuO3, Li2IrO3 and Sn-substituted Li2Ru0.5Sn0.5O3 and Li2Ir0.5Sn0.5O3 were prepared following the methods of previous reports17,19. Powder X-ray Diffraction data, Supplementary Figs. 1–3, confirm the formation of the compounds. Each of the materials possess O3-type layered structures with honeycomb ordering in the TM plane, Fig. 1a manifesting as the familiar superlattice peaks between 2θ = 18° and 34°. As seen before, there is evidence of some stacking faults between the ordered layers, which result in asymmetric peak broadening of these superlattice peaks, especially for the Sn-substituted samples.

a O3-type layered structure with honeycomb ordering of Li and TM ions within the TM layers. First cycle load curves for b Li2RuO3 and Li2Ru0.5Sn0.5O3 and (c) Li2IrO3 and Li2Ir0.5Sn0.5O3 from 2.0 V to 4.6 V at a current rate of 20 mA g−1 plotted against formal oxidation state of Ru or Ir (in black). Electrochemical cycling is reversible with little voltage hysteresis below +5 (in blue). High voltage charging plateaus are observed in all materials beyond the +5 TM oxidation state. The plateaus are accompanied by significant voltage loss on subsequent discharge in all cases except for Li2IrO3.

The first cycle load curves are shown in Fig. 1b, c and are plotted against the nominal oxidation state of Ru and Ir in each case, since Sn4+ is known to be redox inactive. The electrochemical behaviour is reversible with very little hysteresis when cycling below Ru5+ and Ir5+. When sufficient Li is extracted to exceed the +5 oxidation state on Ru, an extended high voltage plateau is observed followed by an S-shaped discharge. For the iridates, reversibility can be maintained up to +5.5 supported by Ir redox as shown recently by Hong et al.26. Further Li can be extracted beyond this limit in Li2Ir0.5Sn0.5O3 subsequently inducing voltage hysteresis. Li2IrO3 is the only material where TM migration and loss of the honeycomb ordering is avoided upon charging to 4.6 V, in accord with its reversible electrochemical behaviour26,30.

Spectroscopic characterisation of O

Understanding O-redox has proven to be a challenge due in part to the need for techniques capable of determining the nature of O species formed in the bulk. In this study, we have employed X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) in partial fluorescence yield (PFY) mode and high resolution resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS) at the O K-edge, as they offer a direct probe of the electronic states on O at depths of up to 50–100 nm into the sample. XAS probes the empty states above the Fermi level. In RIXS, excitation of core electrons to empty states above the Fermi level results in emission as electrons from filled valance states below the Fermi level relax to the core-hole states. RIXS complements XAS as it provides a direct probe of the valence states on O.

In Fig. 2, we present the O K-edge XAS and RIXS for Li2RuO3 and Li2Ru0.5Sn0.5O3 collected ex situ at different points along the load curve on charge and discharge. Considering first the XAS spectra. For Li2RuO3, on initial charge to the beginning of the plateau, there is a pronounced increase in intensity at the leading edge of the pre-edge (lowest energy peak between 529 and 530 eV) indicating the formation of electron hole states in hybridised Ru–O orbitals consistent with Ru oxidation from +4 to +5, as previously reported17,25. Across the plateau there is no further increase in this region but instead new states appear at 531 eV. After discharge, both of these changes are reversed, and the pre-edge reduces in intensity. The pre-edge for the discharged sample is comparatively broad when compared directly with that of the pristine indicating a rehybridization of the Ru–O bonding between the two samples. The structure has been shown to undergo TM migration during the first cycle and the XAS peak broadening we observe here is consistent with an increase in the local disorder around O. For Li2Ru0.5Sn0.5O3, the pre-edge broadening after the plateau on charge and in the discharged material is more pronounced than Li2RuO3 in line with the greater degree of O-redox and more extensive TM migration for the Sn-substituted material17.

a, d O K-edge XAS spectra collected in bulk sensitive partial fluorescence yield (PFY) mode. Inset figure—load curve showing with coloured dots where on the load curve the spectra were collected. b, e high resolution RIXS line scans at an excitation energy of 531 eV. Spectrum of molecular O2 gas shown for reference in black (reproduced from ref. 35). The RIXS line scans reveal the formation of molecular O2 which is reduced to O2− on discharge. c, f High resolution RIXS maps of the O K-edge pre-edge for cathodes charged to the end of the high voltage plateau. Across the plateau there is an increase in area at 531 eV for both Li2RuO3 and Li2Ru0.5Sn0.5O3. The RIXS maps show that there are no other O–O vibrations.

To interrogate the electronic states formed at 531 eV further, RIXS measurements were performed for each sample at this excitation energy. The emission spectra are plotted as is convention, as energy loss (difference between excitation and emission energy). At the top of charge two new energy loss features become evident, a broad peak at 8 eV and a progression of sharp peaks between 0 and 2 eV, as we observed previously for Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 and Na0.75Li0.25Mn0.75O215,16. The progression of peaks in the 0–2 eV region correspond to the vibrations of a molecular O2 diatomic, also shown in Fig. 235. The emission spectra for a range of excitation energies across the O K-edge for the fully charged electrodes were also measured and are presented as RIXS maps. The data show no evidence of any other vibrational features at different excitation energies. After discharge, these new features are much diminished in intensity indicating reversible electrochemical reduction of molecular O2 has occurred.

The same measurements were also performed for the iridate samples and are presented in Fig. 3. Li2Ir0.5Sn0.5O3 exhibits very similar changes to those described for Li2RuO3 and Li2Ru0.5Sn0.5O3 consistent with the voltage profile observed. On the other hand, the RIXS spectra for Li2IrO3 do not show any evidence for the presence of molecular O2 in the fully charged electrodes. Instead, a strong increase in intensity at the leading edge of the pre-edge is seen when charging Ir beyond the +5 oxidation state. This observation supports the conclusion that the high voltage plateau in Li2IrO3 is associated with Ir rather than O oxidation26. Notably, the XAS spectra for the pristine and discharged electrodes are almost fully superimposable indicating minimal irreversible change to the electronic structure and thus structural stability.

a, d O K-edge XAS spectra collected in bulk sensitive partial fluorescence yield (PFY) mode. Inset figure—load curve showing with coloured dots where on the load curve the spectra were collected. b, e High resolution RIXS line scans at an excitation energy of 531 eV. Spectrum of molecular O2 gas shown for reference in black (reproduced from ref. 35). The RIXS line scans reveal the formation of molecular O2 in Li2Ir0.5Sn0.5O3 which is reduced to O2− on discharge but not in Li2IrO3. c, f High resolution RIXS maps of the O K-edge pre-edge for cathodes charged to the end of the high voltage plateau. The RIXS maps show that there are no other vibrations.

Since the measurements are performed under ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions and the samples had been pumped down overnight under UHV, the electrodes will be fully out-gassed, so any molecular species that are detected are trapped within the bulk of the primary particles. To rule out the possible influence of beam damage inducing molecular O2, we performed all our measurements at low temperature, 20 K, and conducted measurements at the same sample location over a range of timescales. The data presented in Supplementary Fig. 4 show no change in the peak spacing between spectra acquired after 30 s and 1800 s exposure times and only a minor decrease in intensity, which is in line with our previous beam sensitivity studies for molecular O2 in Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O215. In that paper, we also extensively examined the effect of temperature and photon flux and showed that neither of these factors have a detectable influence on the vibrational peak spacing, reinforcing that the O2 observed by RIXS is intrinsic to the cathode.

Although the spectroscopic data show no evidence of O species other than O2, RIXS data were also collected for KO2 and Li2O2 to rule out the possibility of O2− and O22−. The results are presented in Fig. 4 where they are compared directly with the spectra for the Ru and Ir compounds. The peak spacing for Li2O2 around the elastic peak corresponding to the vibrational spectrum is almost exactly half of the peak spacing observed for molecular O2 in the cathodes as clearly seen in the Birge-Sponer plot, Fig. 4b. This is closely in line with the vibrational frequency for O22− which is well known to be half that of molecular O2. For KO2, containing the superoxide moiety O2− of intermediate bond order to O2 and O22−, the peak spacing lies halfway between the two. While some differences in the RIXS spectra for different peroxide and superoxide compounds is possible, the vibrational spectra associated with the elastic peak is determined primarily by the O–O bond length/strength and therefore is characteristic of these species in general. The clear distinction that can be made between O2, O2− and O22− dimers demonstrates the power of high resolution RIXS and provides evidence for the formation of molecular O2 in the Li-rich cathodes.

a High resolution RIXS scans at 531 eV excitation energy for charged cathode samples and a Li2O2 reference collected under identical measurement conditions. KO2 RIXS was collected at 529.6 eV, where O2− vibrations are strongest. Peak spacing consistent with molecular O2 is seen in the case of all cathodes except Li2IrO3 which is not O-redox active. There is no evidence of O22− or O2− vibrations in any of the cathode samples ruling out the presence of peroxides and superoxides. b Birge-sponer plot showing linearly decreasing dependence of peak spacing with vibrational quantum number, n, consistent with the anharmonic oscillations of diatomic molecules.

Discussion

Studies using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) and density functional theory (DFT) pointed to the possibility of peroxo-like O2n− species, where n = 1, 2 or 317,20,25,36. Scanning transmission spectroscopy (STEM) and neutron powder diffraction studies of Li2IrO3, suggested longer peroxo-like dimers (3 < n < 3.3)19. However, excellent though these studies are, it is a challenge for these techniques to identify unambiguously the nature of the oxidised oxygen species. XPS, being an electron emission technique, is, in general, more limited in its ability to measure bulk species than RIXS, which utilises photon emissions, and XPS can often be strongly influenced by surface contributions. Turning to local structural probes, imaging individual O–O defects in the bulk is beyond the capabilities of current STEM techniques and resolving O–O species at such low interatomic separations and concentrations is very challenging for total scattering data. Since they are magnetically complex materials, the 4d and 5d systems defy clear characterisation of oxidised O by either 17O NMR or SQUID. In contrast, the high resolution RIXS that we employ in this study is element specific, probes 50–100 nm deep into the particles, and has allowed us to clearly identify molecular O2 in the bulk of solid materials. High resolution RIXS has already provided evidence that O2− oxidation in 3d TM oxides forms molecular O2 trapped in voids in the bulk particles. This observation is further supported by 17O NMR which not only identifies trapped molecular O2 as the O–O species formed on charge, but also shows that it is present in quantities commensurate with that expected from the charged passed in Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O215.

Our RIXS and XAS results indicate that the O-redox process can be described as molecular O2 formation throughout the cathode, both as evolved O2 at the surface, which has already been demonstrated with operando mass spec19,29, and trapped O2 within the bulk. The 4 and 5d transition metal oxides generally exhibit greater covalency in the TM–O bond than those of their 3d counterparts; associated with the greater TMd-O2p overlap and lower electron repulsion of the larger 4 and 5d orbitals. The results presented here indicate that these more covalent systems bear closer resemblance to the 3d Li-rich materials than previously thought and that any greater covalency in the TM–O bond for 4 and 5d compounds does not suppress molecular O2 formation in favour of other O–O species.

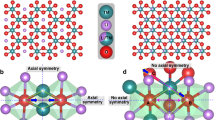

In a recent study, Hong et al. presented Ir L3 XANES data that showed Ir is able to oxidise beyond +5 to +5.5 in Li2IrO3 and Li2Ir0.5Sn0.5O3 before O-redox activity26. In this regime, both materials can cycle reversibly. For Li2Ir0.5Sn0.5O3, charging can be continued beyond +5.5 consequently incurring O oxidation, TM migration, peroxide (O22−) formation and voltage hysteresis. Our results show an absence of any oxidised oxygen species in Li2IrO3 in accord with the Ir L3 XANES data presented by Hong et al26. However, for Li2Ir0.5Sn0.5O3 the high resolution RIXS shows the presence of molecular O2, rather than peroxide, as the only form of oxidised oxygen species. High resolution RIXS also reveals molecular O2 is present in the ruthenates in contrast to previous reports of peroxides. The ability of RIXS to show an absence of signal for materials supported exclusively by TM-redox and identify oxidised O when it is present in O-redox materials demonstrates its utility for probing oxidised O species. Ir5+, low spin t2g4, has 1 more electron than Ru5+, t2g3, and it is spin-paired, Fig. 5a. Removal of this higher energy spin down electron occurs at a lower voltage than for an electron on Ru5+. The oxidation of O2− sits between the energies for Ir5+/6+ and Ru5+/6+ such that Ir5+ is oxidised before O2− (i.e. at a lower voltage) whereas Ru5+ is not. The voltages of the redox couples derived from dQ/dV analysis of the electrochemical load curves in Fig. 1 are shown in Fig. 5b. The substitution of Ir for Sn limits the Ir redox capacity increasing the amount of extractable Li available to be charge compensated by O-redox explaining why substantial O oxidation is observed for Li2Ir0.5Sn0.5O3.

a d electron configurations for different oxidation states of Ru and Ir. The spin down electron on Ir5+ is at a higher energy and hence oxidised at a lower voltage than removal of a spin up electron from the stable d3 configuration of Ru5+. Since oxidation of Ir5+ occurs before O2−/O2 and Ru5+ does not, we place O2−/O2 between the two redox couples in the figure (b). The values of the redox couples shown in black in (b) were obtained from dQ/dV analysis extracted from the data in Fig. 1.

Much like the 3d TM Li-rich O-redox systems, those based on 4d and 5d TM elements exhibit TM migration, loss of honeycomb ordering, O-loss and voltage hysteresis. The vibrational spectra measured by RIXS now also show that molecular O2, rather than peroxides or peroxo-like species, are formed in all of these systems indicating TM–O covalency has limited effect on the bond order of the O–O dimer in the bulk of the cathodes. Future research efforts on Li-rich cathodes should focus on chemical and structural modifications other than covalency of the host network to improve their performance.

Methods

Materials preparation

Li2RuO3 and Li2Ru0.5Sn0.5O3 were synthesised from RuO2 (99.9% Alfa Aesar), SnC2O4 (98% Alfa Aesar) and Li2CO3 (99+% Merck) mixed in the appropriate ratios with 10% excess Li2CO3. Calcination was performed in air at 800 °C for 6 h, 900 °C for 12 h and then 1100 °C for 12 h with intermediate grinding. Li2IrO3 and Li2Ir0.5Sn0.5O3 were synthesised from IrO2 (99.9% Alfa Aesar), SnO2 (99.9% Alfa Aesar) and Li2CO3 (99+% Merck) mixed in the appropriate ratios with 10% excess Li2CO3. Calcination was performed in air at 1000 °C for 12 h and 900 °C for 36 h with intermediate grinding. The as-prepared materials were transferred to an Ar-filled glovebox and handled under inert atmosphere for all further manipulations. Li2O2 (95%, ACROS Organics) and KO2 (Sigma Aldrich) standards were used as supplied.

Electrochemistry

Self-supporting electrode films were prepared by grinding the as-synthesised materials with acetylene black and polytetrafluoroethylene in a 8:1:1 mass ratio in a pestle and mortar and subsequently calendared. Electrochemical cycling was performed in coin cells with LP30 electrolyte and a lithium metal foil counter electrode. Cells were disassembled at different states of charge and the electrodes rinsed with dry dimethylcarbonate for ex situ analysis.

Powder X-ray diffraction

Powder X-ray diffraction patterns were obtained for the as-prepared materials using a Cu source Rigaku SmartLab diffractometer equipped with a Ge(220) double bounce monochromator and without exposure to air. Reitveld profile refinements were performed using the GSAS suite of programs.

X-ray absorption spectroscopy and resonant inelastic X-ray scattering

X-ray absorption spectroscopy and resonant inelastic X-ray scattering data were obtained at the I21 beamline, Diamond Light Source. Samples were transferred to the spectrometer using a vacuum transfer suitcase to avoid air exposure and were pumped down to UHV and left to fully degas overnight. O K-edge spectra were obtained in partial fluorescence mode for bulk sensitivity. RIXS line scans were recorded at five different sample locations and averaged together. RIXS maps were collected at 0.2 eV intervals in excitation energy. All measurements were performed at 20 K to minimise any possible beam damage.

Data availability

Supporting research data has been deposited in the Oxford Research Archive and is available under this DOI: 10.5287/bodleian:eyyG8ovA0.

References

Koga, H. et al. Different oxygen redox participation for bulk and surface: a possible global explanation for the cycling mechanism of Li1.20Mn0.54Co0.13Ni0.13O2. J. Power Sources 236, 250–258 (2013).

Seo, D.-H. et al. The structural and chemical origin of the oxygen redox activity in layered and cation-disordered Li-excess cathode materials. Nature. Chemistry 8, 692–697 (2016).

Muhammad, S. et al. Evidence of reversible oxygen participation in anomalously high capacity Li- and Mn-rich cathodes for Li-ion batteries. Nano Energy 21, 172–184 (2016).

Lu, Z. & Dahn, J. R. Understanding the anomalous capacity of Li/Li[NixLi(1/3−2x/3)Mn(2/3−x/3)]O2 cells using in situ X-Ray diffraction and electrochemical studies. J. Electrochem. Soc. 149, A815–A815 (2002).

Johnson, C. S. et al. The significance of the Li2MnO3 component in ‘composite’ xLi2MnO3·(1−x)LiMn0.5Ni0.5O2 electrodes. Electrochem. Commun. 6, 1085–1091 (2004).

Koga, H. et al. Reversible oxygen participation to the redox processes revealed for Li1.20Mn0.54Co0.13Ni0.13O2. J. Electrochem. Soc. 160, A786–A792 (2013).

Lu, Z., Beaulieu, L. Y., Donaberger, R. A., Thomas, C. L. & Dahn, J. R. Synthesis, structure, and electrochemical behavior of Li[NixLi1/3-2x/3Mn2/3-x/3]O2. J. Electrochem. Soc. 149, A778–A778 (2002).

Assat, G. et al. Direct quantification of anionic redox over long cycling of Li-Rich NMC via hard X-ray photoemission spectroscopy. ACS Energy Lett. 3, 2 (2018).

Luo, K. et al. Charge-compensation in 3d-transition-metal-oxide intercalation cathodes through the generation of localized electron holes on oxygen. Nat. Chem. 8, 684–691 (2016).

Gent, W. E. et al. Coupling between oxygen redox and cation migration explains unusual electrochemistry in lithium-rich layered oxides. Nat. Commun. 8, 2091 (2017).

Tran, N. et al. Mechanisms associated with the “Plateau” observed at high voltage for the overlithiated Li1.12(Ni0.425Mn0.425Co0.15)0.88O2 System. Chem. Mater. 20, 4815–4825 (2008).

Armstrong, A. R. et al. Demonstrating oxygen loss and associated structural reorganization in the lithium battery cathode Li[Ni0.2Li0.2Mn0.6]O2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 8694–8698 (2006).

Croy, J. R., Balasubramanian, M., Gallagher, K. G. & Burrell, A. K. Review of the U.S. Department of Energy’s “deep Dive” Effort to Understand Voltage Fade in Li- and Mn-Rich Cathodes. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 2813–2821 (2015).

Chen, H. & Islam, M. S. Lithium Extraction Mechanism in Li-Rich Li2MnO3 involving oxygen hole formation and dimerization. Chem. Mater. 28, 6656–6663 (2016).

House, R. A. et al. First-cycle voltage hysteresis in Li-rich 3d cathodes associated with molecular O2 trapped in the bulk. Nature. Energy 5, 777–785 (2020).

House, R. A. et al. Superstructure control of first-cycle voltage hysteresis in oxygen-redox cathodes. Nature 577, 502–508 (2020).

Sathiya, M. et al. Reversible anionic redox chemistry in high-capacity layered-oxide electrodes. Nat. Mater. 12, 827–835 (2013).

Sathiya, M. et al. High Performance Li2Ru1-yMnyO3 (0.2 ≤ y ≤ 0.8) cathode materials for rechargeable lithium-ion batteries: their understanding. Chem. Mater. 25, 1121–1131 (2013).

McCalla, E. et al. Visualization of O-O peroxo-like dimers in high-capacity layered oxides for Li-ion batteries. Science 350, 1516–1521 (2015).

Saubanère, M., McCalla, E., Tarascon, J.-M. & Doublet, M.-L. The intriguing question of anionic redox in high-energy density cathodes for Li-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 9, 984–991 (2016).

Perez, A. J. et al. Strong oxygen participation in the redox governing the structural and electrochemical properties of Na-rich layered oxide Na2IrO3. Chem. Mater. 28, 8278–8288 (2016).

Rozier, P. et al. Anionic redox chemistry in Na-rich Na2Ru1−ySnyO3 positive electrode material for Na-ion batteries. Electrochem. Commun. 53, 29–32 (2015).

ben Yahia, M., Vergnet, J., Saubanère, M. & Doublet, M.-L. Unified picture of anionic redox in Li/Na-ion batteries. Nat. Mater. 18, 496–502 (2019).

Xie, Y., Saubanère, M. & Doublet, M.-L. Requirements for reversible extra-capacity in Li-rich layered oxides for Li-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 10, 266–274 (2017).

Sathiya, M. et al. Electron paramagnetic resonance imaging for real-time monitoring of Li-ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 6, 6276 (2015).

Hong, J. et al. Metal-oxygen decoordination stabilizes anion redox in Li-rich oxides. Nat. Mater. 18, 256–265 (2019).

Mortemard de Boisse, B. et al. Intermediate honeycomb ordering to trigger oxygen redox chemistry in layered battery electrode. Nat. Commun. 7, 11397 (2016).

Mortemard de Boisse, B. et al. Coulombic self-ordering upon charging a large-capacity layered cathode material for rechargeable batteries. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–7 (2019).

Yu, Y. et al. Revealing electronic signatures of lattice oxygen redox in lithium ruthenates and implications for high-energy Li-ion battery material designs. Chem. Mater. 31, 7864–7876 (2019).

Kobayashi, H., Tabuchi, M., Shikano, M., Kageyama, H. & Kanno, R. Structure, and magnetic and electrochemical properties of layered oxides, Li2IrO3. J. Mater. Chem. 13, 957–962 (2003).

Li, L. et al. Probing electrochemically induced structural evolution and oxygen redox reactions in layered lithium iridate. Chem. Mater. 31, 4341–4352 (2019).

Charles, N. et al. Toward establishing electronic and phononic signatures of reversible lattice oxygen oxidation in lithium transition metal oxides for Li-ion batteries. Chem. Mater. 32, 5502–5514 (2020).

Rouxel, J. Anion–cation redox competition and the formation of new compounds in highly covalent systems. Chem. - A Eur. J. 2, 1053–1059 (1996).

Sharpe, R. et al. Redox chemistry and the role of trapped molecular O2 in Li-rich disordered rocksalt oxyfluoride cathodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 21799–21809 (2020).

Arhammar, C. et al. Unveiling the complex electronic structure of amorphous metal oxides. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 6355–6360 (2011).

Foix, D., Sathiya, M., McCalla, E., Tarascon, J.-M. & Gonbeau, D. X-ray photoemission spectroscopy study of cationic and anionic redox processes in high-capacity Li-ion battery layered-oxide electrodes. J. Phys. Chem. C. 120, 862–874 (2016).

Acknowledgements

P.G.B. is indebted to the EPSRC, including the SUPERGEN programme (EP/L019469/1), the Henry Royce Institute for Advanced Materials (EP/R00661X/1, EP/S019367/1, EP/R010145/1, EP/L019469/1) and the Faraday Institution (FIRG007, FIRG008) for financial support. We acknowledge Diamond Light Source for time on I21 under proposal MM25589-1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.A.H. conceived and conducted the experimental work. R.A.H., J.J.M. and J.P. working closely with K.-J. Z. and team S.A., A.N., M.G.F. conducted, processed and interpreted the RIXS and soft XAS measurements. G.J.R. assisted collecting supporting data. R.A.H. and P.G.B. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

House, R.A., Marie, JJ., Park, J. et al. Covalency does not suppress O2 formation in 4d and 5d Li-rich O-redox cathodes. Nat Commun 12, 2975 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23154-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23154-4

This article is cited by

-

Trapped O2 and the origin of voltage fade in layered Li-rich cathodes

Nature Materials (2024)

-

Delocalized electron holes on oxygen in a battery cathode

Nature Energy (2023)

-

Slab gliding, a hidden factor that induces irreversibility and redox asymmetry of lithium-rich layered oxide cathodes

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Understanding voltage hysteresis and decay during anionic redox reaction in layered transition metal oxide cathodes: A critical review

Nano Research (2023)

-

Transition metal migration and O2 formation underpin voltage hysteresis in oxygen-redox disordered rocksalt cathodes

Nature Communications (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.