Abstract

Study design

Comparative case study

Objectives

To elevate the voices of and capture the lived environmental and systems experiences of persons with spinal cord injury (PWSCI) and their caregivers, in transitions from inpatient rehabilitation to the community. Also, to examine the perceived and actual availability and accessibility of services and programs for this group.

Setting

Inpatient rehabilitation unit and community in Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Methods

As a comparative case study, this research included multiple sources of data including brief demographic surveys, pre- and post-discharge semi-structured interviews, and conceptual mapping of services and programs for PWSCI and caregivers in Calgary, Canada (dyads). Three dyads (six participants) were recruited from an inpatient rehabilitation unit at an acute care facility, from October 2020 to January 2021. Interviews were analyzed using the Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis approach.

Results

Dyads described transition experiences from inpatient rehabilitation to community as uncertain and unsupported. Breakdowns in communication, COVID-19 restrictions, and challenges in navigating physical spaces and community services were identified by participants as concerns. Concept mapping of programs and services showed a gap in identification of available resources and a lack of services designed for both PWSCI and their caregivers together.

Conclusions

Areas for innovation were identified that may improve discharge planning and community reintegration for dyads. There is an intensified need for PWSCI and caregiver engagement in decision-making, discharge planning and patient-centered care during the pandemic. Novel methods used may provide a framework for future SCI research in comparable settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The transition home for people with acute spinal cord injury (SCI) is fluid, starts in hospital [1,2,3] and can last for years in the community [4]. Various stakeholders have identified transitions in care as a gap in the continuum of SCI care, and previous work suggests that this needs to be better supported [5]. Persons with SCI (PWSCI) have reported social, financial, physical, and emotional changes after injury and described challenges in translating skills they developed on inpatient rehabilitation (rehab) units to community environments [4, 6,7,8,9]. The contrived inpatient environment does not always prepare PWSCI for inaccessible community environments [9].

SCI not only affects the lives of people with the injury; people close to the PWSCI (i.e., spouses, family members, or members of the person’s close social network [7]) are also impacted and may become informal, primary caregivers (herein referred to as “caregivers”). Caregiver-related research has included objective and subjective measures of burden [10, 11], stress [12], resilience, and coping [13].

There is a paucity of research in three areas related to community living post-injury. First is the shared experience of PWSCI and caregiver dyads (herein referred to as “dyads”); only 10 articles were found that studied dyads [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. Second is qualitative research on the lived experiences of dyads; five of the 10 articles were quantitative studies [14,15,16,17,18] and three were study protocols (one was a scoping literature review [19], and two were randomized-controlled trials of different psycho-educational family group interventions [20, 21]). Only two articles used qualitative methodology but did not investigate transitional experiences of dyads from hospital to home [22, 23]. Third is the limited research on the transition experience of dyads, from inpatient rehab to community living, specifically, using qualitative semi-structured interviews as the primary method of data collection. This study was novel in its research question, methods, participant population, and the experiences investigated.

The research team had two objectives in this study. The first was to capture the voices and lived environmental and systems experiences of PWSCI and their caregivers, as they transition from inpatient rehab to the community. The second was to examine the perceived and actual availability and accessibility of services and programs for this group.

Methods

Study design

This project was a comparative case study, which involves two or more cases [24]; here, a case refers to a dyad, involving a PWSCI and their caregiver. Participants were recruited within the last month of their inpatient rehab stay and followed up four to six weeks post-discharge.

Demographic surveys were administered before each first round interview. Semi-structured interviews were conducted pre- and post-discharge with each dyad, to capture their lived environmental and systems experiences longitudinally. Environmental experiences include home and community environments, transportation, and aspects of physical access [25, 26]. Systems experiences refer to those within the continuum of care [5], navigation of services [5, 6], and self-perceived preparedness at discharge [2].

The interview guides were developed with input from the Patient Liaison at the inpatient rehab unit. Questions in first round interviews inquired about dyads’ feelings towards their upcoming discharge, services and programs that may be helpful in the community, and about social and medical supports they may have upon returning home. The second-round questions followed up on responses from the first interview and inquired about dyadic experiences navigating home and community environments and services, among other questions.

Conceptual mapping of services and programs was used to compare the perceived availability and accessibility of services and programs with actual availability. This comparison allowed for insight into what services people were aware of, where gaps in transitional support exist, and how COVID-19 has impacted the availability and accessibility of services.

Recruitment

To develop rich descriptions and comparisons of cases as per the objectives of comparative case studies [24] and Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis [IPA] [27], recruitment was restricted to three dyads, which prioritized depth rather than breadth of representation. Patients in the last month of their inpatient stay were recruited from the rehab unit at an acute care facility in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. PWSCI and caregivers who were older than 18 years, spoke English, consented to participate as a dyad, and who both resided within Calgary city limits were eligible. In accordance with ethical guidelines, potential participants on the unit were approached by the SCI Nurse Clinician with information posters and consent-to-contact forms prior to a member of the study team contacting PWSCI and caregivers by email or phone and obtaining informed verbal consent.

Data collection

Demographic surveys were administered using Qualtrics. Interviews were conducted by telephone or Zoom from October 2020 to January 2021. Services and programs identified by dyads were listed, and a structured search process was conducted using Google to identify others. All services and programs were then characterized by the following information: details of what was offered, eligibility criteria, location/s, and times of operation. Where possible, information about the impact of COVID-19 to service delivery was documented.

Data analysis

Interviews were manually transcribed from recordings to password-protected Word documents and uploaded to NVivo12. All speakers’ names were replaced with codes, to anonymize the data. Interview transcripts were analyzed using IPA [4, 28]. Using IPA, researchers seek to examine personal lived experiences of research participants [28].

Interview analysis began by reviewing each transcript separately, to refamiliarize the analyst with the data and preliminary notes were recorded in a research log. The objective was to determine and describe the lived experiences of the dyads; therefore, themes were developed inductively from within the data in an emergent fashion [29]. Triangulation occurred between the analyst and members of the research team with methodological and clinical expertise. Recurrent themes evolved throughout the second round of interviews and thematic saturation was achieved to create rich descriptions as per IPA [27] and comparative case study research [24].

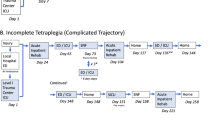

Once the information about services and programs was collected, the concept map was developed. The software Diagrams.net was used to produce the conceptual map (Fig. 1).

Results

Participant demographics

Three dyads (six people) participated in this study and there was full retention of participants from first- to second-round interviews. Each PWSCI and caregiver identified as spouses and each dyad reported living together (Table 1).

Conceptual map of services and programs

The conceptual map is broadly separated into services and programs identified by dyads during the interviews (gray boxes), and those that were not (white boxes) (Fig. 1). Within those two groups, services and programs were divided into those for PWSCI, those for caregivers, and those for both. Changes to service-delivery due to COVID-19 were represented in this visual with dashed lines through boxes. Seven services and programs were identified by dyads during interviews; all of which were for PWSCI. No services were identified for caregivers nor for both people. The research team identified an additional 26 services and programs for PWSCI, four services for caregivers and none for both, although services were not contacted to determine how dyads could be accommodated.

Semi-structured interviews

Two themes are presented from first-round interviews and one theme from second-round interviews.

Theme one: being a part of the discharge process

Theme one includes dyads’ experiences preparing for discharge, their perceived involvement in discharge planning, and the meaning of these experiences. Participants described a fragmented discharge-planning process. Two of the three PWSCI explained that they had to advocate for themselves, to fill their psychosocial and financial needs while on the unit. A third PWSCI described receiving information about their discharge and community reintegration only in the last week of their inpatient stay (see Box 1a).

Information was not always communicated by the healthcare team transparently and in a timely manner. Whether it was disjointed communication with healthcare professionals, or an overall lack of information, all PWSCI described feeling confused, rushed, or as if discharge planning was done in isolation from the healthcare team.

There was a general sense among both PWSCI and their caregivers of no or limited clarity about the discharge process. One PWSCI identified struggling to envision how the rehab activities on the unit would translate to their home environment. Another dyad described confusion about how they could access SCI-related services once discharged from the hospital (see Box 1b). A lack of communication between healthcare providers and the dyad in this situation resulted in concerns that the PWSCI had to take responsibility for referrals to community services.

Lastly, while all three dyads described uncertainty about the services and programs available in the community, there was variation in how this uncertainty impacted people. One dyad described not having any questions about community services and programs, but the PWSCI described not knowing what else to ask, because there were so many unknowns (see Box 1c). The caregiver of that dyad described feeling isolated from discharge planning due to the COVID-19 visitation restrictions on the unit. Because she felt disconnected from the discharge planning process, she did not prioritize learning about community services pre-discharge, and instead prioritized preparing their home for her spouse’s return.

Theme two: rehabilitation and transition in the time of a pandemic

The Provincial Government’s COVID-19 public health restrictions had significant impacts on discharge preparation. Many services that the rehab unit usually offered were suspended, such as weekend passes, home visits by Occupational and Physical Therapists, and community outings with Recreation Therapists. Without these available services, the PWSCI returned to their home and community for the first time, unsupported, on the day of their discharge.

Additionally, visitation restrictions at the facility prohibited caregivers from entering the hospital and visiting their spouses. Due to the staggered timing of each participant’s inpatient stay, the first dyad reported that the caregiver had access to the hospital while the PWSCI was preparing to discharge. For example, the first dyad was able to practice using a set of stairs together, so that the caregiver could learn techniques to support their spouse in their own home. This dyad explained these joint sessions were useful and they expected to use that knowledge once home.

The second dyad described that the caregiver only had visitation access to the rehab unit for a short time during their spouse’s stay, due to evolving outbreaks and subsequent lockdowns. The caregiver felt disconnected from what was happening, and described feeling responsible for the discharge planning that had to be done in the community. One small example was the process of obtaining a parking permit for the dyad’s home (see Box 2). The third dyad reported that the caregiver did not have any access to the hospital for the duration of their spouse’s stay on the rehab unit, nor did the caregiver have direct contact or communication with the healthcare team.

Theme three: community services and accessibility

This theme encompasses dyadic experiences in navigating different aspects of the community, which were addressed in second-round interviews once PWSCI had returned home. Sub-themes include Healthcare in the Community, Out in the Community, and Navigating Services.

Healthcare in the community

Two dyads described barriers to receiving necessary primary healthcare services. One PWSCI described frustration when she encountered hesitancy from her family physician in treating her SCI-related health needs (see Box 3a). Another dyad described feeling unsupported by the healthcare system when the PWSCI encountered a minor secondary complication during the holiday season. The caregiver described calling their family physician and the rehab unit Nurse Practitioner without success (see Box 3b). The caregiver identified that planning for discharge should have included coordination with the dyad’s family physician and believed that it may have mitigated the challenges the dyad faced in receiving necessary medical care when the PWSCI required it.

Out in the community

One dyad described multiple instances of inaccessibility of public spaces, such as entering their family physician’s office due to poorly designed ramps and entranceways, as well as public washrooms and department stores with heavy manual doors and narrow aisles that made navigating the environment with a wheelchair difficult. The dyad recognized that the options for improving public accessibility are limited and suggested it would have been helpful to practice in such environments with the rehab therapists prior to discharge.

Although one dyad did not have experience navigating community spaces at the time of the second-round interview, both people speculated that their family physician’s office and dentist’s office would be challenging to access. The PWSCI wondered whether the inpatient rehab team could have provided the dyad with a selection of accessible offices for these services.

Navigating services

All PWSCI identified that they were unsure what services were available for them in the community. The PWSCI in two dyads were on the waitlist to begin outpatient rehab at the Community Accessible Rehabilitation (CAR) program at the time of the second interview, and both described needing that program to determine what other services and programs were available to them. Both individuals had been in contact with Spinal Cord Injury Alberta (SCI-AB), an organization that provides community-based services and referrals to persons with physical disabilities. However, they both planned to ask therapists during their appointments at the CAR program about other available services and programs. The third PWSCI felt the accessibility of SCI-AB was hindered due to the virtual nature of their introduction to the program (see Box 3c).

The third PWSCI did not identify plans to access additional services in the community beyond the CAR program, private physiotherapy, and rehab services. This dyad identified that they did not know of any services they would find useful; however, they acknowledged their uncertainty about the breadth of services and programs they believed may be available.

Discussion

This study provides a novel perspective, having examined a relatively short period of time between inpatient rehab and community living, compared to previous studies in the literature [4]. Considering the overlaid context of the COVID-19 pandemic, this study provides novel insights into the need for enhancements, not restrictions during unprecedented circumstances.

The experiences described in this study support those of Cott [2] who reported that persons with disabilities felt under-supported, abandoned by the healthcare system, and isolated once back home. Work by Lindberg, Kreuter, Taft, and colleagues [3] highlighted a lack of patient-centered care and the importance of patient participation in rehab. In the present study, the lack of caregiver participation and engagement indicated the need for them to also be partners in care, rehab, and discharge planning.

There was inadequate transitional support, beginning inpatient, that created identifiable barriers and preventable challenges for dyads. The continuum of care included gaps in knowledge and subsequent referrals from inpatient to community services. PWSCI described passive experiences while preparing for discharge because they were not adequately engaged in decision-making. Caregivers were disenfranchised from the planning process, which had negative impacts on their preparation process and placed the burden of preparing for the discharge on their shoulders.

Dyads were unsure in both first- and second-round interviews about the services that were available to them. Participant testimonies of this uncertainty are supported by the visual representation and comparison offered in the conceptual map. Dyads only identified a fraction of the services and programs that are available in Calgary. Additionally, dyads struggled to obtain necessary care from their family doctors and had to self-advocate by educating their providers and navigating gaps in services to fill their needs.

Results from this study highlight the critical importance of providing context-relevant rehab and activities. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic all passes and outings were suspended, leaving PWSCI to practice their adapted mobility skills solely inpatient and often without their caregiver present. PWSCI did not experience their home or community environments until discharge, which dyads found challenging.

Patient and caregiver engagement emerged as particularly important given the changes and limitations in service delivery because of the pandemic. Streamlined coordination between dyads, inpatient, and community healthcare providers could support accessible and effective care for PWSCI and caregivers as they reintegrate into the community. The concept mapping exercise identified multiple community-based supports, although none for dyads specifically, and participants were unaware of most of them. This signals a need for enhanced awareness among inpatient staff to help facilitate the transition back home.

Limitations and future research

The eligibility criteria for this study excluded perspectives from rurally located patients, patients without a caregiver, and participants who did not speak English fluently. This study did not examine experiences that may be impacted by social identity or social position, and future research could focus on the impact of various positions including gender, culture, race, or income. COVID-19 impacted the recruitment process and the interviews, which were all done virtually. Not having in-person interaction with study participants may have affected the researcher’s rapport with participants and therefore the experiences they shared. This study was not conceptualized through a community-based, participatory action approach. Future research must include dyads as research partners when developing a research question and methods, through to data analysis and knowledge translation. Lastly, the small number of participants included in this study may limit the transferability of these findings—future research should include larger and more diverse number of participants.

Further studies could explore how to safely provide passes and outings from the rehab unit during a pandemic. Sustaining community-based activities in unprecedented times such as the COVID-19 pandemic would increase the adaptability of these integral services and bolster discharge planning.

Conclusion

Based on the evidence reviewed for this study, there is a paucity of SCI literature exploring the dyadic experience during the immediate transition from rehab to community. Our exploration of systems and environmental experiences across the SCI continuum of care from a dyadic perspective contributes novel methods and findings to SCI research, and insights for clinical teams to consider integrating into care. Firstly, while transparent decision-making is a vital component of patient- and family-centered care, it is not enough. Dyads need to be partners in decision-making, rather than passive recipients of decisions made on their behalf. Secondly, the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted that support for community integration is not only required but must be bolstered. Lastly, innovations in service delivery must be grounded in patient and caregiver engagement to ensure people have the information and confidence they need to transition into home and community-life following a significant and life-changing event.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Praxis Spinal Cord Institute. Rick Hansen spinal cord injury registry community report. Vancouver: Praxis Spinal Cord Institute; 2019. p. 36 http://praxisinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/RHSCIR_CommunityReport_2017.pdf

Cott CA. Client-centred rehabilitation: client perspectives. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26:1411–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280400000237.

Lindberg J, Kreuter M, Taft O, Person LO. Patient participation in care and rehabilitation from the perspective of patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2013;51:834–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2013.97.

Nunnerley JL, Hay-Smith EJC, Dean SG. Leaving a spinal unit and returning to the wider community: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35:1164–73. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2012.723789.

Milligan J, Lee J, Smith M, Donaldson L, Athanasopoulos P, Basset-Spiers K, et al. Advancing primary and community care for persons with spinal cord injury: key findings from a Canadian summit. J Spinal Cord Med. 2018;43:223–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790268.2018.1552643.

Backus D, Gassaway J, Smout RJ, Hseih CH, Heinemann AW, DeJong G, et al. Relation between inpatient and post-discharge services and outcomes 1 year postinjury in people with traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94:165–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2013.01.012.

Conti A, Garrino L, Montanari P, Dimonte V. Informal caregivers’ needs in discharge from the spinal cord unit: analysis of perceptions and lived experiences. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38:159–67. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2015.1031287.

Van de Velde D, Bracke P, Van Hove G, Josephsson S, Vanderstaete G. Perceived participation, experiences from persons with spinal cord injury in their transition period from hospital to home. Int J Rehabil Res. 2010;33:345–55. https://doi.org/10.1097/MRR.0b013e32833cdf2a.

Booth S, Kendall M. Benefits and challenges of providing transitional rehabilitation services to people with spinal cord injury from regional, rural, and remote locations. Aust J Rural Health. 2007;15:172–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2017.02.009.

Castellano-Tejedor C, Lusilla-Palacios P. A study of burden of care and its correlates among family members supporting relatives and loved ones with traumatic spinal cord injuries. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31:948–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215517709330.

Tough H, Brinkhof MW, Siegrist J, Fekete C. Subjective caregiver burden and caregiver satisfaction: the role of partner relationship quality and reciprocity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98:2042–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2017.02.009.

Charlifue SB, Botticello A, Kolakowsky-Hayner SA, Richards JS, Tulsky DS. Family caregivers of individuals with spinal cord injury: exploring the stresses and benefits. Spinal Cord. 2016;54:732–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2016.25.

Simpson G, Jones K. How important is resilience among family members supporting relatives with traumatic brain injury or spinal cord injury?. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27:367–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215512457961.

Fekete C, Tough H, Brinkhof MWG, Siegrist J. Does well-being suffer when control in productive activities is low? A dyadic longitudinal analysis in the disability setting. J Psychosom Res. 2019;122:13–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.04.015.

Scholten EWM, Ketelaar M, Visser-Meily JMA, Roels EH, Kouwenhoven M, POWER Group, et al. Prediction of psychological distress among persons with spinal cord injury or acquired brain injury and their significant others. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;101:2093–2102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2020.05.023.

Scholten EWM, Tromp MEH, Hillebregt CF, de Groot S, Ketelaar M, Visser-Meily JMA, et al. Mental health and life satisfaction of individuals with spinal cord injury and their partners 5 years after discharge from first inpatient rehabilitation. Spinal Cord. 2018;56:598–606. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-017-0053-z.

Tough H, Brinkhof MWG, Siegrist J, Fekete C, SwiSCI Study Group. Social inequalities in the burden of care: a dyadic analysis in the caregiving partners of persons with a physical disability. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-019-1112-1.

Tough H, Brinkhof MWG, Siegrist J, Fekete C. The impact of loneliness and relationship quality on life satisfaction: a longitudinal dyadic analysis in persons with physical disabilities and their partners. J Psychosom Res. 2018;110:61–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.04.009.

Moreno A, Zidarov D, Raju C, Boruff J, Ahmed S. Integrating the perspectives of individuals with spinal cord injuries, their family caregivers, and healthcare professionals from the time f rehabilitation admission to community integration: protocol for a scoping study on SCI needs. BMJ Open. 2017;7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014331.

Dyck DG, Weeks DL, Gross S, Smith CL, Lott HA, Wallace AJ, et al. Comparison of two psycho-educational family group interventions for improving psycho-social outcomes in persons with spinal cord injury and their caregivers: a randomized controlled trial of multi-family group intervention versus an active education control condition. BMC Psychol. 2016;4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-016-0145-0.

Soendergaard PL, Wolffbrandt MM, Biering-Sørensen F, Nordin M, Schow T, Arango-Lasprilla JC, et al. A manual-based family intervention for families living with the consequences of traumatic injury to the brain or spinal cord: a study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-019-3794-5.

Osborne JB, Rocchi MA, McBride CB, McKay R, Gainforth HL, Upper R, et al. Couples’ experiences with sexuality after spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2022.2040611.

Jeyathevan G, Cameron JI, Craven BC, Munce SEP, Jaglal SB. Re-building relationships after a spinal cord injury: experiences of family caregivers and care recipients. BMC Neurol. 2019;19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-019-1347-x.

Ylikoski P, Zahle J. Case study research in the social sciences. Stud Hist Philos Sci. 2019;78:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsa.2019.10.003.

Reinhardt JD, Middleton J, Bökel A, Kovindha A, Kyriakides A, Hajjioui A, et al. Environmental barriers experienced by people with spinal cord injury across 22 countries: results from a cross-sectional survey. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;101:2144–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2020.04.027.

Whiteneck G, Meade MA, Djikers M, Tate DG, Bushnik T, Forchheimer MB. Environmental factors and their role in participants and life satisfaction after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;8:1793–803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2004.04.024.

Hale ED, Treharne GJ, Kitas GD. Qualitative methodologies II: a brief guide to applying Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis in musculoskeletal care. Musculoskelet Care. 2008;6:86–96. https://doi.org/10.1002/msc.113.

Smith JA, Osborn M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis as a useful methodology for research on the lived experience of pain. Br J Pain. 2015;9:41–2. https://doi.org/10.1177/2049463714541642.

Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigour using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5:80–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Patient Liaison and her community contacts for contributing to study design, and the SCI Nurse Clinician who supported participant recruitment. Finally, the authors would like to thank the dyads who participated in this study, for sharing their experiences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JB conducted interviews and developed the conceptual map. KM and MM supported JB in interview analysis and all authors developed and revised this paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for this study was granted by the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (CHREB) at the University of Calgary [REB20-1023]. We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during this research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Brady, J., Mouneimne, M. & Milaney, K. Environmental and systems experiences of persons with spinal cord injury and their caregivers when transitioning from acute care to community living during the COVID-19 pandemic: a comparative case study. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 9, 8 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-023-00561-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-023-00561-x