Abstract

Background

Children with serious illness suffer from symptoms at the end of life that often fail to be relieved. An overview is required of healthcare interventions improving and decreasing quality of life (QOL) for children with serious illness at the end of life.

Methods

A systematic review was performed in five databases, January 2000 to July 2018 without language limit. Reviewers selected quantitative studies with a healthcare intervention, for example, medication or treatment, and QOL outcomes or QOL-related measures, for example, symptoms, for children aged 1–17 years with serious illness. One author assessed outcomes with the QualSyst and GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) Framework; two authors checked a 25% sample. QOL improvement or reduction was categorized.

Results

Thirty-six studies met the eligibility criteria studying 20 unique interventions. Designs included 1 randomized controlled trial, 1 cross-sectional study, and 34 cohort studies. Patient-reported symptom monitoring increased QOL significantly in cancer patients in a randomized controlled trial. Dexmedetomidine, methadone, ventilation, pleurodesis, and palliative care were significantly associated with improved QOL, and chemotherapy, stem cell transplant, and hospitalization with reduced QOL, in cohort studies.

Conclusions

Use of patient-controlled symptom feedback, multidisciplinary palliative care teams with full-time practical support, inhalation therapy, and off-label sedative medication may improve QOL. Curative therapy may reduce QOL.

Impact

-

QOL for children at the end of life may be improved with patient-controlled symptom feedback, multidisciplinary palliative care teams with full-time practical support, inhalation therapy, and off-label sedative medication.

-

QOL for children at the end of life may be reduced with therapy with a curative intent, such as curative chemotherapy or stem cell transplant.

-

A comprehensive overview of current evidence to elevate currently often-failing QOL management for children at the end of life.

-

New paradigm-level indicators for appropriate and inappropriate QOL management in children at the end of life.

-

New hypotheses for future research, guided by the current knowledge within the field.

-

Various healthcare interventions (as described above) could or might be employed as tools to provide relief in QOL management for children with serious illness, such as cancer, at the end of life, and therefore could be discussed in pediatrician end-of-life training to limit the often-failed QOL management in this population, cave the one-size-fits-all approach for individual cases.

-

Multidisciplinary team efforts and 24/7 presence, especially practical support for parents, might characterize effective palliative care team interventions for children with serious illness at the end of life, suggesting a co-regulating link between well-being of the child partly to that of the parents

-

Hypothesis-oriented research is needed, especially for children with nonmalignant disorders, such as genetic or neurological disorders at the end of life, as well as QOL outcomes for intervention research and psychosocial or spiritual outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite medical advancements in therapy and treatment, a substantial proportion of children with serious illness such as cancer or neuromuscular conditions will still die of their disease. Yearly, between 24.4 and 75.3% of deaths for children between 1 and 17 are caused by serious illness in European and non-European countries, according to a 2017 population-level study.1,2 Partly as a result of medical–technical developments and expanding possibilities of treatment, care for children often remains focused on cure and life prolongation even in the last months of life.3,4,5,6 There is a growing recognition that care should focus on maintaining the quality of life (QOL) at the end of life.7

In order to provide adequate health care at the end of life for children with serious illness, an overview is required, of which healthcare interventions have negative and/or positive effects on children’s QOL at the end of life. Such an overview is currently not available. Gathering evidence on the effects of healthcare interventions is indicated as one of pediatric oncology’s key priorities.8 A complete overview of all known possible effects of healthcare interventions on QOL and related measures is necessary to support healthcare providers in safe and effective decision making,9 and for the construction of quality measures, such as quality indicators and evidence-based guidelines.10

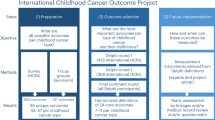

Our main objective was to systematically review peer-reviewed quantitative literature for evidence about (associations indicating) the effects of healthcare interventions on QOL or QOL-related measures at the end of life for children with a serious illness. Specific research questions were: (1) in which designs, populations, and settings were healthcare interventions studied with regard to QOL and QOL-related measures in children at the EOL?; (2) what healthcare interventions were studied?; (3) what healthcare interventions (are associated with) significantly increase(d) or reduce(d) QOL below α 0.05?; and (4) what was the overall study quality and certainty of evidence?

Methods

Registration

The protocol was registered in the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD 42018105109) and published.11 The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) were followed, see Supplementary Information 1.

Search strategy

We identified studies by searching in five electronic databases: in MEDLINE, EMBASE, CENTRAL, CINAHL, and Web of Science. A search was performed on July 7, 2018. The language was not limited; the time was limited to publications from 2000 or later. We excluded studies before 2000 as care prior to this date is likely to differ from that of later generations,12 and a scoping review indicated research is scarce before 2000. The MEDLINE search strategy was developed alongside information specialists, based on the Peer Review of Electronic Strategies (PRESS) guidelines.13 The electronic MEDLINE search strategy is provided in Supplementary Information 2.

Study eligibility criteria

Study designs

Interventional and observational designs with quantifiable results, such as randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and cohort and cross-sectional studies. Observational designs were included due to the suspected scarcity of research on children at the end of life9,14 and to capture any associations of interventions with QOL.

Population

Children with serious illness aged from 1 up to and including 17 years at the end of life, meaning children suffering from a serious illness who are within the last year of their lives. Acutely ill children, neonates, and young adults were excluded; the end-of-life periods of these populations differ for diagnosis, prognosis, and care context. The mean, median, and/or range of age had to be situated between 1 and 17 years. If a paper discussed children in general terms without age reference, the study was also included. The children were considered to be at the end of life when the study described their sample as being at the end of life at the time of admission of the health intervention, using explicit terminology referring to the end of life, such as “terminally ill,” “near death,” or “dying.” Serious illness was defined as having at least one complex chronic condition, according to the definition (in ICD-10-codes) poised in recent literature.15

Intervention

Healthcare interventions applied to the population as described above. The WHO definition for health interventions was used: “any act performed for, with or on behalf of a person or population whose purpose is to assess, improve, maintain, promote or modify health, functioning, or health conditions’.16

Outcomes

QOL outcomes relating to the QOL of the child. We included QOL as such as outcome, but also QOL-related measures: outcomes that could be present on a QOL-scale, such as, among others, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual symptoms, and treatment success, burden, intensity, or toxicity. A broad selection of outcomes was necessary for a thorough overview. We only included outcomes at the level of the child, and excluded outcomes for other stakeholders, such as QOL of parents or medical staff.

Study selection

All records were exported to the reference management software Endnote (Version X7.1). Duplicated records were removed. Using Covidence review management software, four authors (V.P., A.l.-S., K.B., and N.S.P.) screened the titles and abstracts. V.P. screened all records, and A.l.-S, K.B., and N.S.P. independently screened one-third of all records. Three authors (V.P., A.l.-S., and N.S.P.) screened full texts. V.P. screened all records, and A.l.-S. and N.S.P. each independently screened half of the records. Any discrepancies were discussed between the two reviewers in question. In case of disagreement, a third reviewer (K.B. or J.v.d.W.t.B.) was consulted. One author (V.P.) hand-searched the reference lists and contacted authors of the selected studies for additional relevant publications.

Data extraction

The following variables were extracted as described in the publication(s): Author(s), title, publication date, article language, journal, data collection, country, aim, healthcare intervention(s), QOL or QOL-related outcome, results for outcome (for main scales, subscales, and sub-analyses), QOL measurement, children’s age (mean, median, range, interquartile range; also if the children themselves were not participating), intervention duration, start and end of intervention in days before death, number of participants (children who were directly or indirectly assessed), and children’s illness. The following variables were extracted and classified according to the judgment of the authors of this review: study design, who reported the QOL or proxy of QOL outcome, setting, and illness category. Data were extracted from text, tables, and graphs. If data were missing, authors were not contacted for additional information. The authors of selected publications were contacted to verify the extracted data.

Study quality assessment, certainty of evidence, and data analysis

Data extraction, quality assessment, and grading of certainty of the evidence were performed by V.P. A 25% sample was checked by other researchers (A.-l.S. and N.S.P.). The quality of each individual study was assessed with the quantitative checklist within the QualSyst Tool17 (scale ranging from 0 to 1.0). The certainty of evidence was assessed with the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) approach.18 We categorized certainty of evidence per healthcare intervention as high (very certain that effect is close to a true effect), moderate (moderately certain), low (limited certainty), or very low (little certainty).

Data synthesis

We summarized results in overview tables. We grouped healthcare interventions and outcomes according to clinical homogeneity and categorized healthcare interventions into two categories, pharmacological or non-pharmacological, and QOL outcomes into five categories as emergent from the data. Original summary measures were kept. Significant results were categorized for QOL improvement or reduction.

Results

Study selection

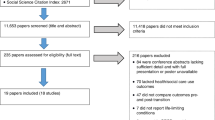

As shown in Fig. 1, 8614 studies were identified in MEDLINE, EMBASE, CENTRAL, CINAHL, and Web of Science, and 8578 studies were excluded. Thirty-six studies met the eligibility criteria.19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54

Study characteristics

Studies mainly had a retrospective cohort (29/36, 81%) or prospective cohort design (5/36, 14%), as illustrated in Table 1. One study had a experimental design (RCT) (1/36, 3%), and another study had a cross-sectional design (1/36, 3%). In two-thirds, children with cancer were studied (23/36, 64%). In one-third (12/36), multiple disorders were studied, for example, a combination of cancer and other disorders. Mean or median age of children ranged from 3.4 years to 17 years. In total, 2493 children were studied. Most healthcare interventions were administered in a hospital setting (16/36, 44%). Outcomes were mostly reported by parents (19/36, 53%).

Studied healthcare interventions and outcomes

Twenty different healthcare interventions were studied, as shown in Table 1. Seventeen percent (6/36) had QOL as such as an outcome. QOL as such was measured with the PedsQL 4.0 (one study), the Health Utilities Index (one study), the Survey About Caring for Children with Cancer (one study), or an undefined numeric rating scale (three studies). Eighty-three percent of studies (30/36) used QOL-related measures, such as symptoms. Mainly physical symptoms were studied (33/36, 92%).

Significant results

Table 2 shows all significant results. In total, nine interventions revealed statistically significant associations with QOL.

Improved QOL

One pharmacological intervention (dexmedetomidine) and three non-pharmacological interventions (noninvasive mechanical ventilation, pleurodesis, and electronic patient-reported symptom monitoring) were significantly associated with improved QOL (-related measures). Dexmedetomidine was associated with decreased pain, noninvasive ventilation and pleurodesis with decreased cardiopulmonary symptoms, and electronic patient-reported symptom monitoring with improved emotional QOL. Results for dexmedetomidine, pleurodesis, and noninvasive mechanical ventilation resulted from retrospective cohort studies, while the result for patient-reported symptom monitoring was from an RCT.

Two interventions had associations with improved and reduced QOL, but mostly with improved QOL: palliative care was associated with higher quality of life as such, less pain, less dyspnea, more fun, more meaning in life, and better communication, but more constipation and energy loss. Methadone was associated with less pain, less fatigue, and less insomnia, but more dyspnea.

Reduced QOL

One pharmacological intervention (IV chemotherapy) and one non-pharmacological intervention (hospitalization) were significantly associated with reduced QOL and QOL-related measures; both interventions were associated with increased dyspnea. Both results came from the same retrospective cohort study.

One intervention was associated both with improved and reduced QOL, but most associations were with reduced QOL: stem cell transplant was associated with a higher number of physical and psychological symptoms, fatigue, diarrhea, sadness, and fear, but with reduced constipation.

Detailed characteristics of significant results can be found in Table 3.

Characteristics of healthcare interventions with significant results

Table 4 shows the characteristics of healthcare interventions with significant results. Most interventions with significant results were non-pharmacological. Often doses, procedures, duration, and timing of admission were not available. Palliative care programs were mostly physical and psychosocial, and always included a multi-professional team. Most programs had a 24/7 on-call service and helped with coordination of care.

Study quality and evidence certainty

Study quality

QualSyst scores ranged from 0.27 to 0.86, as indicated in Table 1. Qualsyst scores were generally low due to the absence of control groups and the absence of matched comparison groups, inadequate subject/comparison selection or source of information, insufficient description of subject and comparison characteristics, insufficient operationalization, small sample sizes, non-validated measurement tools, unreported estimates of variance, and no controlling for confounding. Detailed QualSyst scores can be found in Supplemental Information 3.

Evidence certainty

Ratings for evidence certainty were very low for all healthcare interventions and related outcomes, except for electronic patient-reported symptom monitoring that had moderate certainty of evidence for emotional QOL, as presented in Table 2 and Supplemental information 4.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic literature review mapping and synthesizing the effects, and associations indicating effects, of healthcare interventions on QOL in children with serious illness at the end of life, according to the best available evidence. We found 36 eligible studies with a total of 20 different healthcare interventions that were studied in relation to QOL or QOL-related measures. Only one RCT was found, and mainly cohort studies were used to study health interventions and QOL in children at the end of life. Mainly children with cancer were studied. Overall eight medications, ten treatments, and two methods for delivery of care were found to be studied for QOL in terms of healthcare interventions. Six healthcare interventions were significantly associated with improved QOL, and three interventions were significantly associated with reduced QOL in children with serious illness at the end of life. In general, certainty of evidence was very low, mainly due to a lack of measures for bias reduction in cohort studies. The body of evidence shows fragmented research, as different outcomes were studied for various healthcare interventions, and the same outcome was rarely studied for the same intervention, due to which no meta-analysis was not possible.

Interpretation of results

Our systematic review revealed various indications could be made for appropriate QOL management in children with serious illness at the end of life.

Electronic symptom monitoring feedback and patient-controlled interventions are hypothesized to be one of the cornerstones of appropriate pediatric end-of-life management. Electronic symptom monitoring feedback was the only healthcare intervention that reliably improved QOL in children with cancer at the end of life. It seems that a noninvasive form of QOL monitoring can hold a place in the provision of appropriate care for these children. An important element may be the fact the system was patient controlled, an aspect that is also found in the multiple patient-controlled analgesia studies within our selection of papers.36,39 These papers, although not statistically generalizable due to the methods used, showed mainly associations with improved QOL. Therefore, besides the importance of symptom feedback systems being implemented in hospital service for children, one may also carefully hypothesize that patient-controlled interventions are an important aspect of appropriate care in children at the end of life.

Off-label sedative medication and treatments seem to present adequate symptom control in the population at hand. Both QOL-increasing medications that emerged from our selection, methadone and dexmedetomidine, are sedative in nature, and efficient in relieving pain, the main troublesome symptom in children at the end of life.55,56 The main portion of the studies without use of inferential statistics in this review were also sedative in nature (propofol, various opioids, nerve blocks, and forgoing of artificial hydration and feeding). The widespread reporting of sedative medication use could point to its importance for this population in terms of appropriate care provision. It is also to be noted that both significantly effective medications and some non-inferentially studied interventions are off-label for the pediatric population, and off-label prescription may be needed in certain children for appropriate symptom control.

Furthermore, improved breathing could be central to improved QOL for at least a part of the population. Two lung treatments were shown to have associations with improved QOL. Dyspnea is reported to be one of the most disturbing symptoms for children at the end of life.57

Palliative care interventions seem to be effective for families with children with serious illness at the end of life when they are multidisciplinary, provide 24/7 round-the-clock assistance, medical help for the child, and practical or even emotional help for the parents. Our summary of results for palliative care interventions showed that all significant results in this category resulted from palliative care teams with these characteristics. The clear presence of practical assistance for parents suggests that the QOL of the child also increases when parents receive practical and emotional help. The latter hypothesis is supported by neurodevelopmental research, which has previously shown co-regulation mechanisms between parents and children, especially mothers, are associated with child self-regulation, and this interaction is suggested as a hypothesis to also be of crucial importance in appropriate pediatric end-of-life care.58,59 There was one cohort study out of five that indicated some negative associations of palliative care with QOL, which could be a result of a measurement error, or the palliative care intervention in question could have been inappropriate, possibly due to intensive psychological counseling, which seemingly characterized this intervention. It could be hypothesized that children at the end of life cannot handle intensive psychological treatment that only provides benefits in the long term.

Curative treatment seemingly negatively impacts the QOL of children at the end of life, although this should be further tested. Both chemotherapy and stem cell transplant significantly reduced QOL and were explicitly stated to be of curative nature. In adults, negative effects of these interventions are often used as an indicator for inappropriate care, and it is generally believed care at the end of life in children should avoid disease-oriented treatment.3,60,61,62,63 The majority of parents still prefer chemotherapy over comfort care at the end of life,64 which probably results from a parent’s understandable hope that their child will survive, and highlights the need for measures that indicate when a child has no realistic chance of survival to assist parents in treatment decision making. Some traditional disease-oriented treatments such as chemotherapy are also used as a comfort measure, for example, to control pain,14 and it is worth investigating which application forms and doses provide symptom relief.

Lastly, there are indications that end-of-life context and place of care can influence QOL: hospitalization significantly improved chances for severe dyspnea in one study we found. However, this result might also reflect the fact that children with severe symptoms are more often hospitalized. Hospitalization is considered stressful for children, but might also provide the only facility for relief in cases where symptoms are severe.

Study quality and evidence certainty

Evidence certainty was moderate for electronic patient-reported symptom reporting (measured via RCT) and very low for all other interventions (cohort studies). RCTs are often not feasible or ethically permissible for children at the end of life, due to the vulnerable population. Most studies, therefore, employed non-interventional, retrospective designs. However, measures that could control bias in these designs were absent in most cohort studies, such as controlling for confounders.

Certainty of evidence was low for studies, yet a stringent quality assessment tool was used (QualSyst), and the standards of this tool are extremely high. Research in pediatric end-of-life care research, due to its ethical and practical confinements, will very rarely score very high on the measures of certainty of evidence compared to other fields. However low the certainty of some evidence, it remains important to generate new hypotheses for further research based on the current state-of-the-art and build theories based on all indications we can gather, rather than to throw away the baby out with the bathwater. In order to gain further knowledge in this field without depleting costly resources and a vulnerable population, hypothesis-driven research should be thought out in a careful manner that provides a balance between quality of evidence and practicality in studying the population at hand. Significant results were plenty in our selection of studies, and therefore provide ample opportunity for new research questions and construction of main indications for appropriate QOL management in children at the end of life. The overview of evidence in this review allows us to suggest novel hypotheses based on the current state-of-the-art end-of-life care research for children. The calculated risks and sensitivities as a result of a stringent quality analysis should not lead to the conclusion that no evidence is present, yet should seek to falsify the hypotheses that are generated through the current research in order to avoid research waste and to more rapidly progress research into pediatric QOL management.

Research gaps and recommendations emerging from this review

While 20 healthcare interventions have been studied, certain healthcare interventions have not been studied yet for their effects, or the results were not published. Some common healthcare interventions did not surface in our review, such as gastronomy tubes that the majority of children (67.5%) receive at the end of life.65

Studies for nonmalignant disorders are lacking: Mainly cancer patients were studied, while half of child deaths resulting from serious illness are due to nonmalignant conditions. Parents with children with nonmalignant conditions report care to be under-resourced and unresponsive, in contrast to parents of children with cancer.66

Studies for nonphysical outcomes are lacking: Mostly physical symptoms were studied. Pain, for example, was researched often in our review, probably due to systematically available and routinely employed measures with international scoring boards (e.g., FACES, the nonverbal pain scale), resulting in widely and rapidly available data in chart reviews, aside from being the main symptom children suffer at the end of life.67 However, children and their parents also indicate psychological, psychosocial, and existential concerns besides physical ones.57,68

Future research recommendations are methodologically and content-oriented. Methodologically, more robust, prospective, interventional research should be conducted. When an RCT is not feasible, designs should still use necessary measures to control bias, such as restriction, or matching of the population for confounders. Confidence intervals should be reported. Outcome measures validated for the population at hand should be used, for example, the Pediatric Advanced Care QOL Scale for children with advanced cancer.69 In order to bypass scarce availability of the population, the implementation in hospitals of systematic patient-reported monitoring could be used to create big data QOL sets and gather more evidence in a systematic manner.9,70 As patient-reported symptom monitoring was shown to be beneficial for the child’s QOL at the end of life in our review, and patient-reported outcomes were mentioned in previous research as an indicator of appropriate child health care,71 patient-reported outcomes might be used also for research data collection, providing a database that can be used and spares children of additional questionnaires, causing the population to be less overloaded and bypassing recall and parent–child discrepancy. However, appropriate privacy measures should be taken in this regard, for example, in the case of adolescent–parent conflict. Furthermore, clinically ambiguous interventions that are employed in children at the end of life, for example, antibiotics or clinical trials, should be looked into for their effect on QOL. Ideally, the evaluation of interventions is again done via big databases generated via patient-controlled symptom monitoring systems. Effective interventions for children with nonmalignant disorders could be investigated. The hypothesis that practical support for parents improves QOL of the child, emerging from interpretation of our results, could be further reviewed or be incorporated into intervention research.

Practical recommendations for hospital management are that (self-administered) QOL questionnaires for children are electronically and systematically implemented into pediatric hospital wards by boards and management staff, as has previously already been advocated by previous pediatric oncology research.72 QOL questionnaire administering has shown to provide benefits in singling out high-risk patients in other pediatrics fields,73 shown benefits to improve the mood of children with cancer,19 and could advance pediatric QOL management as a field considerably by providing valuable (anonymized) data. Furthermore, patient-controlled interventions might be implemented routinely into pediatric wards, for example, by providing patient-controlled analgesia or by providing tablets for children to fill out daily questionnaires, although implementation should be carefully monitored.

Practical recommendation for individual case management are that pediatricians in training are presented with the various interventions that are possible and for now are shown to be effective in (some) children with serious illness at the end of life. Knowledge of the possibility of, for example, sedative/off-label medication and inhalation therapy can guide the pediatrician with a more well-equipped toolbelt for the rare and therefore often difficult symptom management of the dying child, and provide at least some theoretical grounds for practice.

Strengths and weaknesses

Our systematic review is the first to systematically identify the quantitative evidence of the effects of healthcare interventions on QOL and QOL-related measures for children with serious illness at the end of life. Study execution was meticulous: PRISMA guidelines were used for protocol and reporting and a Cochrane systematic review course was followed. The search strategy was validated and peer reviewed by an Information Specialist. Multiple reviewers selected studies using predetermined selection criteria. Our review also has certain limitations. The search strategy was constructed to be comprehensive, but still might have overlooked studies with relevant results, which was remedied by hand-searching references and contacting the first authors for additional papers. No case studies, qualitative studies or gray literature were included.

Conclusion

There are indications that patient-controlled symptom feedback systems, multidisciplinary palliative care teams, sedative medication, and treatments directed at ameliorating breathing could improve QOL for children at the end of life. Curatively oriented treatments are carefully suggested to reduce QOL for children at the end of life.

Future research should include hypothesis-driven studies, more robust designs whenever possible, controlling for confounding, nonmalignant populations, validated outcome measures, and inclusion of QOL outcomes in intervention research, in order to generate more and verify current conclusions about (in)appropriate health care for children at the end of life.

References

Håkanson, C. et al. Place of death of children with complex chronic conditions: cross-national study of 11 countries. Eur. J. Pediatr. 176, 327–335 (2017).

INSPQ. Soins Palliatifs de Fin de Vie Au Québec: Définition et Mesure d’indicateurs, Vol. 53 (INSPQ, 2006).

Johnston, E. E. et al. Disparities in the intensity of end-of-life care for children with cancer. Pediatrics 140, e20170671 (2017).

Tang, S. T. et al. Pediatric end-of-life care for Taiwanese children who died as a result of cancer from 2001 through 2006. J. Clin. Oncol. 29, 890–894 (2011).

Kassam, A. et al. Predictors of and trends in high-intensity end-of-life care among children with cancer: a population-based study using health services data. J. Clin. Oncol. 35, 236–242 (2017).

Park, J. D. et al. Trends in the aggressiveness of end-of-life care for Korean pediatric cancer patients who died in 2007-2010. PLoS ONE 9, 1–5 (2014).

Cohen, J. & Deliens L. A Public Health Perspective on End of Life Care (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, 2012).

Hinds, P., Pritchard, M. & Harper, J. End-of-life research as a priority for pediatric oncology. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 21, 175–179 (2004).

Brock, K., Mark, M., Thienprayoon, R. & Ullrich, C. in Palliative Care in Pediatric Oncology (eds Wolfe, J., Jones, B. L., Kreicbergs, U. & Jankovic, M.) 287–314 (Springer, 2018).

Goldman, A., Hain, R. & Liben, S. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Care for Children (Oxford University Press, 2012).

Piette, V. & et al. Influence of health interventions on quality of life in seriously ill children at the end of life: a systematic review. Syst. Rev. 8, 1–8 (2019).

Rosenberg, A. R. & Wolfe, J. Approaching the third decade of paediatric palliative oncology investigation: historical progress and future directions. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 1, 56–67 (2017).

McGowan, J. et al. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 75, 40–46 (2016).

Drake, R. & Chang, E. Palliative Care of Pediatric Populations. Textbook of Palliative Care 1209–1224 (2019).

Feudtner, C., Feinstein, J. A., Zhong, W., Hall, M. & Dai, D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: Updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 14, 1–7 (2014).

WHO. International Classification of Health Interventions (ICHI) (eds MacLeod, R. D. & Van den Block, L.) (WHO, 2012).

Kmet, L. M., Lee, R. C. & Cook, L. S. Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields (Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research, 2004).

Balshem, H. et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Raring the qualty of evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 64, 401–406 (2011).

Wolfe, J. et al. Improving the care of children with advanced cancer by using an electronic patient-reported feedback intervention: results from the PediQUEST randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 32, 1119–1127 (2014).

Korzeniewska-Eksterowicz, A. Palliative sedation at home for terminally ill children with cancer. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 48, 968–974 (2014).

Schindera, C. et al. Predictors of symptoms and site of death in pediatric palliative patients with cancer at end of life. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 31, 548–552 (2014).

Brook, L., Vickers, J. & Pizer, B. Home platelet transfusion in pediatric oncology terminal care. Med. Pediatr. Oncol. 40, 249–251 (2003).

Gans, D. et al. Impact of a pediatric palliative care program on the caregiver experience. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 17, 559–565 (2015).

Madden, K., Mills, S. & Dibaj, S. Methadone as the initial long-acting opioid in children with advanced cancer. J. Palliat. Med. 21, 1317–1321 (2018).

Groh, G. Specialized home palliative care for adults and children: differences and similarities. J. Palliat. Med. 17, 803–810 (2014).

Groh, G. Specialized pediatric palliative home care: a prospective evaluation. J. Palliat. Med. 16, 1588–1594 (2013).

Vollenbroich, R. et al. Effectiveness of a pediatric palliative home care team as experienced by parents and health care professionals. J. Palliat. Med. 15, 294–300 (2012).

Kuhlen, M., Schlote, A., Borkhardt, A. & Janen, G. Häusliche Palliativversorgung von Kindern: Eine Meinungsumfrage bei verwaisten Eltern nach unheilbarer onkologischer Erkrankung. Klin. Padiatr. 226, 182–187 (2014).

Hoffer, F. A. et al. Pleurodesis for effusions in pediatric oncology patients at end of life. Pediatr. Radiol. 37, 269–273 (2007).

Chong, P. H., De Castro Molina, J. A., Teo, K. & Tan, W. S. Paediatric palliative care improves patient outcomes and reduces healthcare costs: evaluation of a home-based program. BMC Palliat. Care 17, 1–8 (2018).

Friedrichsdorf, S. J. et al. Improved quality of life at end of life related to home-based palliative care in children with cancer. J. Palliat. Med. 18, 143–150 (2015).

Thrane, S. E., Maurer, S. H., Cohen, S. M., May, C. & Sereika, S. M. Pediatric palliative care: a five-year retrospective chart review study. J. Palliat. Med. 20, 1104–1111 (2017).

Hooke, M. C. et al. Propofol use in pediatric patients with severe cancer pain at the end of life. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 24, 29–34 (2007).

Hohl, C. M. et al. Methotrimeprazine for the management of end-of-life symptoms in infants and children. J. Palliat. Care 29, 178–185 (2013).

Rapoport, A., Shaheed, J., Newman, C., Rugg, M. & Steele, R. Parental perceptions of forgoing artificial nutrition and hydration during end-of-life care. Pediatrics 131, 861–869 (2013).

Taylor, M., Jakacki, R., May, C., Howrie, D. & Maurer, S. Ketamine PCA for treatment of end-of-life neuropathic pain in pediatrics. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 32, 841–848 (2015).

Burns, J., Jackson, K., Sheehy, K. A., Finkel, J. C. & Quezado, Z. M. The use of dexmedetomidine in pediatric palliative care: a preliminary study. J. Palliat. Med. 20, 779–783 (2017).

Postovsky, S., Moaed, B., Krivoy, E., Ofir, R. & Ben Arush, M. W. Practice of palliative sedation in children with brain tumors and sarcomas at the end of life. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 24, 409–415 (2007).

Schiessl, C., Gravou, C., Zernikow, B., Sittl, R. & Griessinger, N. Use of patient-controlled analgesia for pain control in dying children. Support Care Cancer 16, 531–536 (2008).

Ullrich, C. et al. End-of-life experience of children undergoing hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: parent and provider perspectives and patterns of care. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 39, 331–332 (2010).

Urtubia, B. F., Bravo, A. T., Rodríguez Zamora, N., Torres, C. P. & Barria, L. C. Uso de opiáceos en niños con cáncer avanzado en cuidados paliativos. Rev. Chil. Pediatr. 87, 96–101 (2016).

Dickens, D. S. Comparing pediatric deaths with and without hospice support. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 54, 746–750 (2010).

Rodríguez Zamora, N., Palacios, L. D. & Bull, M. C. Programa Nacional de Cuidado Paliativo para niños con cáncer avanzado en Chile. Revisión Med. Paliat. 21, 15–20 (2014).

Davies, D., Devlaming, D. & Haines, C. Methadone analgesia for children with advanced cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 51, 393–397 (2008).

Bosch-Alcaraz, A. La ventilación no invasiva mejora el confort al paciente paliativo pediátrico. Enfermería Intensiv. 25, 91–99 (2014).

Varma, S., Friedman, D. L. & Stavas, M. J. The role of radiation therapy in palliative care of children with advanced cancer: clinical outcomes and patterns of care. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 64, 1–7 (2016).

Flerlage, J. E. & Baker, J. N. Methylnaltrexone for opioid-induced constipation in children and adolescents and young adults with progressive incurable cancer at the end of life. J. Palliat. Med. 18, 631–633 (2015).

Anghelescu, D. L., Faughnan, L. G., Baker, J. N., Yang, J. & Kane, J. R. Use of epidural and peripheral nerve blocks at the end of life in children and young adults with cancer: the collaboration between a pain service and a palliative care service. Paediatr. Anaesth. 20, 1070–1077 (2010).

Anghelescu, D. L., Hamilton, H., Faughnan, L. G., Johnson, L.-M. & Baker, J. N. Pediatric palliative sedation therapy with propofol: recommendations based on experience in children with terminal cancer. J. Palliat. Med. 15, 1082–1090 (2012).

Breen, M. An evaluation of two subcutaneous infusion devices in children receiving palliative care. Paediatr. Care 18, 38–40 (2013).

Siden, H. & Nalewajek, G. High dose opioids in pediatric palliative care. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 25, 397–399 (2003).

Saad, R. et al. Bereaved parental evaluation of the quality of a palliative care program in Lebanon. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 57, 310–316 (2011).

Schmidt, P. et al. Did increased availability of pediatric palliative care lead to improved palliative care outcomes in children with cancer? J. Palliat. Med. 16, 1034–1039 (2013).

Wolfe, J. et al. Easing of suffering in children with cancer at the end of life: is care changing? J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 1717–1723 (2008).

McCluggage, H.-L. & Elborn, J. S. Symptoms suffered by life-limited children that cause anxiety to UK children’s hospice staff. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 12, 254–258 (2014).

Jalmsell, L. Symptoms affecting children with malignancies during the last month of life: a nationwide follow-up. Pediatrics 117, 1314–1320 (2006).

Hechler, T. et al. Parents’ perspective on symptoms, quality of life, characteristics of death and end-of-life decisions for children dying from cancer. Klin. Padiatr. 220, 166–174 (2008).

Erdman, K. & Hertel, S. Self-regulation and co-regulation in early childhood—development, assessment and supporting factors. Metacogn. Learn. 14, 229–238 (2019).

Hung, Y. N. et al. Receipt of life-sustaining treatments for taiwanese pediatric patients who died of cancer in 2001 to 2010 a retrospective cohort study. Medicine (U.S.) 95, 1–8 (2016).

Prigerson, H. G. et al. Chemotherapy use, performance status, and quality of life at the end of life. JAMA Oncol. 1, 778–784 (2015).

Lafond, D. A., Kelly, K. P., Hinds, P. S., Sill, A. & Michael, M. Establishing feasibility of early palliative care consultation in pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 32, 265–277 (2015).

Drew, D., Goodenough, B., Maurice, L., Foreman, T. & Willis, L. Parental grieving after a child dies from cancer: is stress from stem cell transplant a factor? Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 11, 266–273 (2014).

Tang, S. T. et al. Aggressive end-of-life care significantly influenced propensity for hospice enrollment within the last three days of life for Taiwanese cancer decedents. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 41, 68–78 (2011).

Tomlinson, D. et al. Chemotherapy versus supportive care alone in pediatric palliative care for cancer: comparing the preferences of parents and health care professionals. CMAJ 183, E1252–E1258 (2011).

DeCourcey, D. D., Silverman, M., Oladunjoye, A., Balkin, E. M. & Wolfe J. Patterns of care at the end of life for children and young adults with life-threatening complex chronic conditions. J. Pediatr. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.09.078 (2017).

Price, J. E., Jordan, J., Prior, L. & Parkes, J. Comparing the needs of families of children dying from malignant and non-malignant disease: an in-depth qualitative study. BMJ Support Palliat. Care 2, 127–132 (2012).

Wolfe, J. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N. Engl. J. Med 342, 326–333 (2000).

Namisango, E., Bristowe, K., Allsop, M. J., Murtagh, F. E. M. & Abas, M. Symptoms and Concerns Among Children and Young People with Life‑Limiting and Life‑Threatening Conditions: A Systematic Review Highlighting Meaningful Health Outcomes (Springer International Publishing, 2018).

Danielle Cataudella. Development of a quality of life instrument for children with advanced cancer: the Pediatric Advanced Care Quality of Life Scale (PAC-QoL). Pediatr. Blood Cancer 61, 1840–1845 (2014).

Leahy, A. B., Feudtner, C. & Basch, E. Symptom monitoring in pediatric oncology using patient-reported outcomes: why, how, and where next. Patient 11, 147–153 (2018).

Bevans, K. & Moon, J. Patient reported outcomes as indicators of pediatric health care quality. Acad Pediatr. 14 (2014).

Hinds, P. et al. PROMIS Pediatric Measures in Pediatric Oncology: valid and clinically feasible indicators of patient-reported outcomes. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 60, 402–408 (2008).

Varni, J. W. & Burwinkle, T. M. The PedsQLTM as a patient-reported outcome in children and adolescents with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: a population-based study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 4, 1–10 (2006).

Acknowledgements

All stages of this study were funded by Research Foundation-Flanders (FWO; grant no. 12V8718). The study sponsors had no role in study design, the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, the writing of the report, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. A.-l.S. is a Predoctoral Fellow at the Research Foundation-Flanders. K.B. is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Research Foundation-Flanders (FWO).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.P. and K.B. conceived the original research idea, oversaw the conceptual and methodological development of the protocol, contributed to the revisions of subsequent drafts of the protocol, developed the search strategy, contributed to the selection, extraction, and assessment process, wrote the first version of the paper, and contributed to the revisions of subsequent drafts of the article. L.D. and J.C. oversaw the conceptual and methodological development of the protocol, contributed to the revisions of subsequent drafts of the protocol, contributed to the development and validation of the search strategy, and contributed to the revisions of subsequent drafts of the article. N.S.P. provided input on the conceptual and methodological development of the protocol, contributed to the revisions of subsequent drafts of the protocol, contributed to development and validation of the search strategy, contributed to the selection, extraction, and assessment process, and contributed to the revisions of subsequent drafts of the article. J.v.d.W.t.B. and A.-l.S. provided input on the conceptual and methodological development of the protocol, contributed to the selection, extraction, and assessment process and contributed to the revisions of subsequent drafts of the article. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

41390_2020_1036_MOESM2_ESM.docx

Supplementary Information: Validated MEDLINE Search Strategy (PubMed Interface); QualSyst Ratings Per Study; GRADE Ratings for Evidence Certainty for Significant Outcomes Per Healthcare Intervention

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Piette, V., Beernaert, K., Cohen, J. et al. Healthcare interventions improving and reducing quality of life in children at the end of life: a systematic review. Pediatr Res 89, 1065–1077 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-020-1036-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-020-1036-x

This article is cited by

-

Appropriateness of end-of-life care for children with genetic and congenital conditions: a cohort study using routinely collected linked data

European Journal of Pediatrics (2023)

-

End of life in patients attended by pediatric palliative care teams: what factors influence the place of death and compliance with family preferences?

European Journal of Pediatrics (2023)

-

Emergency Palliative Cancer Care: Dexmedetomidine Treatment Experiences—A Retrospective Brief Report on Nine Consecutive Cases

Pain and Therapy (2023)