Abstract

Background

There is no consensus on optimal Vitamin D status. The objective of this study was to estimate the extent to which vitamin D status predicts illness duration and treatment failure in children with severe pneumonia by using different cutoffs for vitamin D concentration.

Methods

We measured the plasma concentration of 25(OH)D in 568 children hospitalized with World Health Organization-defined severe pneumonia. The associations between vitamin D status, using the most frequently used cutoffs for vitamin D insufficiency (25(OH)D<50 and <75 nmol/l), and risk for treatment failure and time until recovery were analyzed in multiple logistic regression and Cox proportional hazards models, respectively.

Results

Of the 568 children, 322 (56.7%) had plasma 25(OH)D levels ≥75 nmol/l, 179 (31.5%) had levels of 50–74.9 nmol/l, and 67 (%) had levels <50 nmol/l. Plasma 25(OH)D <50 nmol/l was associated with increased risk for treatment failure and longer time until recovery.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that low vitamin D status (25(OH)D<50 nmol/l) is an independent risk factor for treatment failure and delayed recovery from severe lower respiratory infections in children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

An association between nutritional rickets and pneumonia has been reported for decades (1). In recent years there have been several reports on the associations between subclinical vitamin D deficiency and risk for respiratory infections and development of more severe disease (2, 3, 4). Different immunomodulatory effects may explain these associations (5). Moreover, despite convincing in vitro findings, there are examples of observational studies finding no associations (6), and clinical trials and reviews have been inconclusive about the role of vitamin D (7, 8). These inconsistent findings have led to a discussion on whether hypovitaminosis D is a cause or a consequence of inflammation (9, 10). There is also no consensus on the definition of optimal vitamin D status (11).

Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) is produced in the body in a two-step process. It is primarily produced by UVB radiation of the skin that converts 7-dehydro-cholesterol to pre-vitamin D3, which then undergoes thermal isomerization. Vitamin D3 is also derived from dietary sources such as oily fish, availability of which is often limited. Natural dietary sources of vitamin D2 are also limited to some vegetables such as mushrooms, but both vitamin D2 and vitamin D3 are available in supplements and enriched foods. Vitamin D2, as well as vitamin D3, then undergoes hydroxylation reactions in the liver to form 25(OH)D2 or 25(OH)D3 (calcidiol) and then in the kidneys to form the active vitamin D metabolite, 1.25(OH)2D (calcitriol). Several studies in populations from South Asia have reported high prevalences of hypovitaminosis D, despite living in areas with abundant UVB radiation, and in cultures with and without cultural avoidance of the sun (12, 13, 14, 15). South Asia also has a high burden of respiratory tract infections among children (16, 17). There are few studies on vitamin D status and the outcome of pneumonia in small children. One prospective cohort study observed an association between rickets and hypoxemia and treatment failure in children with World Health Organization-defined very severe pneumonia (18). To elucidate the role of vitamin D status on the outcome of pneumonia, we estimated the associations between vitamin D status and time until recovery or treatment failure in young hospitalized Nepalese children with severe pneumonia using cutoffs of 25(OH)D <50 and <75 nmol/l. These cutoffs are commonly used in the literature and are based upon review reports from the US Institute of Medicine (11), the Endocrine Society (19), and the Paediatric Endocrine Society (20). We also explored whether there were nonlinear associations between 25(OH)D concentrations and illness duration and treatment failure. This was to suggest critical cutoffs for 25(OH)D concentrations.

Methods

Ethical Clearance

The ethics board of the Nepal Health Research Council, Kathmandu, gave ethical clearance for the project and for the consent procedure. Written informed consent was obtained from parents who could read and write, and verbal informed consent was obtained in the presence of a witness from those who were illiterate. The study was conducted according to the guidelines provided in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study Design and Study Population

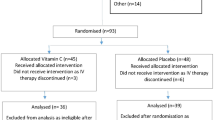

This study was planned as a secondary analysis of data collected from a completed randomized double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial (RCT) conducted in Kanti Children’s hospital, Kathmandu (NCT00252304) (Flow chart of study design in Figure 1). The primary objective of this RCT was to measure the effect of up to 14 days of daily zinc supplementation on time to recovery from severe pneumonia and treatment failure. These results, and predictors for treatment failure and cessation of severe pneumonia, have been described elsewhere (21, 22). The study included children aged 2–35 months with severe pneumonia who were referred to Kanti Children's hospital Emergency or Outpatient departments. Severe pneumonia was defined as cough with duration <14 days and/or difficulty in breathing for ≤72 h with lower chest in-drawing. Initial treatment with benzyl–penicillin and gentamicin was given until clinical improvement, which was defined as absence of any general danger signs (unable to feed or drink, vomiting everything, convulsions, lethargy, or unconsciousness), hypoxia (for 24 h consecutively), and lower chest in-drawing (for 48 h consecutively). Humidified oxygen and intravenous fluids were initiated if required. Treatment failure was defined as requirement of change to second-line therapy (Cefotaxime) because of the persistence of lower chest in-drawing or danger signs despite 48 h of treatment, or development of a new danger sign or hypoxia with deterioration in the patient’s clinical status, or development of complications such as empyema/pneumothorax requiring surgical intervention or admission to the intensive care unit. Long duration was defined as 96 h without clinical improvement (or persistence of severe pneumonia after 96 h), as another 48 h had passed to evaluate whether the patient was improving with the changed drugs. Time to recovery (cessation of severe pneumonia) was defined as the time from enrollment to the beginning of a 24- h consecutive period without lower chest in-drawing, hypoxia, or any danger signs. The children were discharged with advice to the parents to continue amoxicillin and to complete antibiotic treatment of a total of 10 days. Details of both inclusion and exclusion criteria are described previously (21) and are listed in Figure 1.

Data Collection

The children were examined, screened for enrollment, and followed up by trained physicians; the enrolled children were monitored every 8 h. The history of the child’s illness and the results from the physical examination were recorded in a standardized form. Oxygen saturation (SpO2), weight, and height were measured, and a venous puncture for blood specimens and chest radiographs were performed. Nasopharyngeal aspirate (NPA) for detection of respiratory viruses was collected at enrollment. World Health Organization’s definition of hypoxia (SpO2<90%) was used (23). The completed forms with patient data were collected daily by study assistants and the data were entered twice continuously into a relational database. A detailed description of the data collection, the laboratory and technical equipment used, and the treatment given have been presented elsewhere (21).

Study physicians collected 2 ml of venous blood from the enrolled children using heparinized polypropylene syringes (Sarstedt, Numbrecht, Germany). A small amount of this blood was used for bedside measurement of hemoglobin concentration using Hemocue (Ångelholm, Sweden). The blood was then centrifuged and separated and the plasma transferred to Cryovials (Nunc A/S, Roskilde, Denmark) and stored at −70 °C until analysis. The C-reactive protein concentration was determined in this stored plasma using a particle-enhanced immunoturbidimetric assay on a Roche/Hitachi cobas c 501 analyzer (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Alpha-1-acid-glycoprotein (AGP) and albumin concentration were measured in the laboratory of Innlandet Hospital Trust, Lillehammer (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Products GmbH, Marburg, Germany). Nasopharyngeal aspirates were examined for 7 common RNA viruses (Respiratory syncytial virus, Parainfluenza type 1, 2, and 3, Influenza virus A and B, and human metapneumo virus) using a multiplex reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay (Hexaplex Plus; Prodesse Inc, Waukeshaw, WI).

Vitamin D Measurement and Definition of Vitamin D Status

Plasma 25(OH)D was measured using a Cobas 8000 instrument, using reagents from Roche Diagnostics (F. Hoffman-La Roche Ltd., Basel, Switzerland) at Akershus University Hospital (Norway). The method is a quantitative electro-chemiluminescence binding assay, which reports 25(OH)D as the sum of both 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3, the hydroxylated forms of vitamin D2 and vitamin D3, respectively. Analyses were performed according to the Assays Instruction Manual (24). Plasma 25(OH)D cutoffs of 50 nmol/l and 75 nmol/l were used, as these are the most frequently used to define vitamin D sufficiency and insufficiency, respectively (19, 20, 25).

Sample Size and Power Calculation

The study was powered to measure the efficacy of zinc administration on the clinical course of severe pneumonia. In these calculations we assumed that a treatment effect corresponding to a hazard ratio of 1.3 was clinically relevant. The power to detect a significant difference was 80% with these assumptions. The power to detect significant associations between plasma vitamin D status and the selected outcomes was lower because of the relatively low prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency. The powers to detect an odds ratios (OR) of 2 and 3 were 65 and 97% for outcome treatment failure and a prevalence of vitamin D deficiency of 10%.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata, version 14. 25(OH)D concentration was categorized as follows: <50 nmol/l; 50–74.9 nmol/l; and ≥75 nmol/l. Multiple logistic regression and Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the associations between vitamin D status and treatment failure and illness duration as described in the original paper (22). In addition to the crude models, we developed 3 adjusted models for each outcome. The variables included in these models are displayed in the table legends. The associations are expressed as OR and hazard ratios (HR), and a P-value of 0.05 was considered significant. The regression models were also stratified on the basis of the presence or absence of respiratory virus in nasopharynx aspirates (virus positive/virus negative). We used generalized additive models in the statistical software R, version 3.16 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), to explore adjusted nonlinear associations between age or breast-feeding frequency and 25(OH)D concentration (26). In these models, we used the logit link functions when treatment failure was the outcome and a survival function when the outcome was time until recovery.

Results

Child Characteristics and Vitamin D Status

Plasma collected from 568 children with severe pneumonia who were participating in the clinical trial from February 2006 to June 2008 was analyzed for 25(OH)D (Figure 1). The children’s characteristics, listed by vitamin D status, are shown in Table 1. In 169 of the 568 children (29.8%), at least one respiratory virus was detected in the NPA, of which 44.4% was respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Of the 568 children, 322 (56.7%) had plasma 25(OH)D≥75 nmol/l, 179 (31.5%) had levels of 50–74.9 nmol/l, and 67 had levels <50 nmol/l (Table 2). The mean 25(OH)D level varied little throughout the year (Figure 2).

Treatment Failure and Duration of illness

The median (interquartile range, IQR) time to recovery was 44 h (IQR: 25–71). In 209 (35.2%) cases, the criteria for treatment failure were fulfilled. The proportion of children with no clinical improvement after 96 h was 15.3%.

Associations Between Vitamin D Status and Treatment Failure and Longer Duration

Associations between vitamin D status and treatment failure or duration are shown in Table 2. Children with 25(OH)D <50 nmol/l had an increased risk for treatment failure and a longer duration compared with patients with levels ≥75 nmol/l. Children with 25(OH)D <50 nmol/l were also at higher risk for not showing signs of clinical improvement after 96 h. The results for treatment failure and persistence of severe pneumonia after 96 h remained significant after adjusting for potential confounders such as age of the child in months, years of schooling of the mother, z-scores (weight for age, weight for length/height, length/height for age), breast-feeding status, albumin, AGP, hypoxia, C-reactive protein, presence of any danger signs, and consolidation on chest X-ray. Hazard of recovery remained significant after adjusting for background variables, but not after adjusting for clinical/laboratory variables. Children with 25(OH)D levels in the range of 50–74.9 nmol/l were not at an increased risk for treatment failure or longer duration compared with those with higher 25(OH)D concentrations. These results were not altered by a dichotomization of the exposure variable at 50 and 75 nmol/l, rather than using three categories as in Table 2. Stratifying on the basis of virus-positive or -negative NPA, we found stronger associations between vitamin D status and pneumonia outcomes in virus-positive patients (Supplementary Table S1 online). Using 25(OH)D as a continuous variable in the generalized additive models suggests that the odds of treatment failure increases and the hazard of recovery decreases when for each unit the 25(OH)D concentration decreases (Figure 3). These associations were seen only in children in whom we also detected a virus from the NPA and when the 25(OH)D concentrations were lower than ~60 nmol/l (Figure 3).

The association between 25(OH)D concentration and the hazard (log) of recovery and odds(log) of treatment failure among patients NPA-positive for respiratory virus and NPA-negative for respiratory virus. Upper panes: association between hazards of recovery, the left pane in those testing positive for a respiratory virus, to the right, those who tested negative for respiratory virus. Lower panes: associations between the odds of treatment failure and 25(OH)2 concentration. The vertical lines represent the common used cutoffs of 25(OH)D of 50 and 75 nmol/l. All graphs were generated using generalize additive models in R, and the depicted associations are adjusted for age in months, years of schooling of the mother, weight for length/height z-score, length/height for age z-score, breast-feeding, albumin, AGP, hypoxia, CRP, presence of danger sign. AGP, alpha-1-acid-glycoprotein; CRP, C-reactive protein; NPA, nasopharyngeal aspirate.

Discussion

To investigate the association of vitamin D status and outcome of severe childhood pneumonia, we estimated the associations between vitamin D status and illness duration and treatment failure using the two most commonly used cutoffs for vitamin D insufficiency and after adjusting for possible confounders. Children with 25(OH)D concentrations <50 nmol/l had significantly higher risk for longer duration of illness and higher risk for treatment failure compared with children with higher 25(OH)D concentrations. This association was stronger in children who tested positive for one of the common respiratory viruses than in those who did not.

These results could indicate that vitamin D status is an independent risk factor for pneumonia outcomes. Our findings are in line with those from another study in which rickets was associated with a fourfold odds ratio of 30 days’ treatment failure and vitamin D deficiency (25(OH)D <30 nmol/l) was significantly associated with a reduced number of circulating polymorph nuclear neutrophils and persistence of hypoxia (SpO2<88% (ref.18)). The direction of the association, however, may be difficult to determine. A recent literature review concluded that vitamin D status measured during inflammation should be interpreted with care because of the possibility of reverse causality (10). Increased conversion of 25(OH)D to 1.25(OH)2D, with subsequently reduced concentrations of 25(OH)D, is suggested as a possible mechanism (27). However, none of the clinical variables reflecting the severity of illness in our study, such as hypoxia, consolidation on chest X-ray, presence of danger signs, or fever, were associated with vitamin D status. C-reactive protein concentration was not associated with vitamin D status either, which may be inconsistent with the reverse causality hypothesis. In a recent publication in children with bacterial illness, no difference was found between 25(OH)D concentration during bacterial infection and 4 weeks later, and the authors concluded that an acute alteration in vitamin D status seemed unlikely, but they also acknowledged the problem that no pre-infectious samples were taken. Further, in a sample of young Nepalese children, we demonstrated that 25(OH)D concentration was not affected by clinical infection or inflammation (28).

Our results indicate a clinically significant cutoff for vitamin D closer to 50 nmol/l than to 75 nmol/l in this population. When looking at the associations between 25(OH)D and pneumonia outcomes using 25(OH)D as a continuous variable, however, the cutoff was more difficult to define and indicated a value closer to 60 nmol/l. There is still no consensus on the cutoffs for vitamin D sufficiency/deficiency regarding skeletal health. In addition, the role of vitamin D and subsequently the cutoffs for non-skeletal outcomes is still controversial. The US Institute of Medicine (11) and the Paediatric Endocrine Society (20) both argue for 50 nmol/l, whereas the Endocrine Society (19) argues for 75 nmol/l as the optimal cutoff to define Vitamin D insufficiency. All reports acknowledge the need for more research on vitamin D’s role in non-skeletal outcomes. Stratification of the data on the basis of virus-positive or -negative NPA results indicated a stronger relationship between low vitamin D status and pneumonia outcomes in patients in whom we detected a respiratory virus. However, the interpretation of this finding is limited by a lack of bacterial diagnostics and the relatively low detection rate of virus compared with reports from similar populations (29, 30).

Together with the variables consolidation on chest X-ray, hypoxia, and presence of danger signs, we also adjusted the analyses for C-reactive protein, AGP, and albumin when estimating the association between vitamin D status and treatment failure or time to recovery. Inclusion of these variables, reflecting infection severity, resulted in increased effect sizes, indicating that the association between vitamin D and infections is not due to reverse causality. The background variables age, years of schooling of the mother, weight for length/height z-score, length/height for age z-score, and breast-feeding status did not alter the effect estimates substantially. However, inclusion of age in the models also increased the associations of vitamin D status with treatment failure and time to recovery.

We did not include a healthy control group in this study, but we have data on vitamin D status in young children in the same area, both in children with less-severe pneumonia (28) and in healthy infants (31). In the study of children with less-severe pneumonia the percentage of children with vitamin D insufficiency and deficiency was comparable to the findings in this study. The prevalence of insufficiency and deficiency was 2.5-fold higher in studies that included children with pneumonia compared with that in the population of healthy infants. The prevalence of poor vitamin D status was lower in the present study compared with that in other studies of healthy children in Nepal (12, 32). There are currently no government programs or recommendations of vitamin D supplementation or food fortification for infants in Nepal (17, 33). With the reported low content of dietary vitamin D in the traditional Nepalese diet (33), UVB radiation and breast milk are by far the most important sources of vitamin D in young children. Exclusive breast-feeding has been considered inadequate to prevent vitamin D deficiency (13, 34), but recent reports show that vitamin D content in human milk is highly dependent on the mother’s vitamin D status (35, 36). Local sun-exposure habits associated with breast-feeding in Nepal, such as outdoor breast-feeding (12) and the tradition of sun-bathing infants younger than 3 months (37), may therefore be plausible explanations for the relatively high plasma 25(OH)D concentration found in this study. We also found a stable plasma 25(OH)D concentration throughout the year, which may reflect adequate skin-synthesis of vitamin D across the seasons.

There are some limitations in this study. Measuring vitamin D status was a secondary objective of this study. Information on vitamin D status before the infection could have elucidated further the question whether 25(OH)D concentration is affected by an acute-phase reaction, but this was not possible within this study design. Most of the children in our study were vitamin D replete, which limits our statistical power to examine other cutoffs. At the same time we wanted to elucidate the effect of subclinical 25(OH)D concentrations, which would have been difficult with a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency. The optimal way to measure vitamin D status is still debated, and we have used 25(OH)D, which is commonly used, but different methods have different weaknesses. An underestimation of 25(OH)D2 has been reported for similar immunoassays (38), which could have caused false low concentrations. We think this problem would have been larger with a high prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency. Maybe even more importantly, like most other commercial assays, the C3 epimers, which may be present in substantial amounts in infants (39), are not distinguished from the non-epimeric forms in this assay. This could possibly overestimate 25(OH)D concentrations, especially in younger children. Registration of sun exposure and additional foods could also have been helpful in exploring the reasons for the higher plasma 25(OH)D concentrations in the youngest children and for identifying sources of vitamin D. We believe that the large study sample, the well-defined illness, as well as optimal specimen handling are important strengths of this study.

To conclude, we report that children with vitamin D status <50 nmol/l had significantly increased risk for treatment failure and longer illness duration in this study. Our findings indicate that vitamin D status is an independent risk factor for treatment failure and for prolonged severe lower respiratory infections in children, and support the rationale for optimization of vitamin D status to >50 nmol/l in young children. The results should be confirmed by randomized placebo-controlled trials that could target children with pneumonia and confirmed viral etiology.

References

Muhe L, Lulseged S, Mason KE, Simoes EA . Case-control study of the role of nutritional rickets in the risk of developing pneumonia in Ethiopian children. Lancet 1997;349:1801–4.

Karatekin G, Kaya A, Salihoglu O, Balci H, Nuhoglu A . Association of subclinical vitamin D deficiency in newborns with acute lower respiratory infection and their mothers. Eur J Clin Nutr 2009;63:473–7.

McNally JD, Leis K, Matheson LA, Karuananyake C, Sankaran K, Rosenberg AM . Vitamin D deficiency in young children with severe acute lower respiratory infection. Pediatr Pulmonol 2009;44:981–8.

Wayse V, Yousafzai A, Mogale K, Filteau S . Association of subclinical vitamin D deficiency with severe acute lower respiratory infection in Indian children under 5 y. Eur J Clin Nutr 2004;58:563–7.

Greiller CL, Martineau AR . Modulation of the immune response to respiratory viruses by vitamin D. Nutrients 2015;7:4240–70.

Roth DE, Jones AB, Prosser C, Robinson JL, Vohra S . Vitamin D status is not associated with the risk of hospitalization for acute bronchiolitis in early childhood. Eur J Clin Nutr 2009;63:297–9.

Jolliffe DA, Griffiths CJ, Martineau AR . Vitamin D in the prevention of acute respiratory infection: systematic review of clinical studies. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2013;136:321–9.

Yakoob MY, Salam RA, Khan FR, Bhutta ZA . Vitamin D supplementation for preventing infections in children under five years of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;11:CD008824.

Waldron JL, Ashby HL, Cornes MP et al. Vitamin D: a negative acute phase reactant. J Clin Pathol 2013;66:620–2.

Silva MC, Furlanetto TW . Does serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D decrease during acute-phase response? A systematic review. Nutr Res 2015;35:91–6.

Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. Washington, DC: The National Academies,.

Avagyan D, Neupane SP, Gundersen TE, Madar AA . Vitamin D status in pre-school children in rural Nepal. Public Health Nutr 2016;19:470–476.

Bhalala U, Desai M, Parekh P, Mokal R, Chheda B . Subclinical hypovitaminosis D among exclusively breastfed young infants. Indian Pediatr 2007;44:897–901.

Hossain N, Khanani R, Hussain-Kanani F, Shah T, Arif S, Pal L . High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in Pakistani mothers and their newborns. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2011;112:229–33.

Sachan A, Gupta R, Das V, Agarwal A, Awasthi PK, Bhatia V . High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among pregnant women and their newborns in northern India. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;81:1060–4.

Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000-13, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet 2015;385:430–40.

Population Division Ministry of Health and Population Government of Nepal. Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Kathmandu, Nepal: New ERA Kathmandu, 2011.

Banajeh SM . Nutritional rickets and vitamin D deficiency—association with the outcomes of childhood very severe pneumonia: a prospective cohort study. Pediatr Pulmonol 2009;44:1207–1215.

Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:1911–30.

Misra M, Pacaud D, Petryk A, Collett-Solberg PF, Kappy M, Drug, Therapeutics Committee of the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society. Vitamin D deficiency in children and its management: review of current knowledge and recommendations. Pediatrics 2008;122:398–417.

Basnet S, Shrestha PS, Sharma A et al. A randomized controlled trial of zinc as adjuvant therapy for severe pneumonia in young children. Pediatrics 2012;129:701–8.

Basnet S, Sharma A, Mathisen M et al. Predictors of duration and treatment failure of severe pneumonia in hospitalized young nepalese children. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0122052.

World Health Organization. Pocket book of hospital care for children: guidelines for the management of common illnesses with limited resources. WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data 2005, (ISBN 92 4 154670 0), 69–106..

Roche Diagnostics International Ltd. Elecsys Vitamin D total assay. Electro-chemiluminescence binding assay (ECLIA) for the in-vitro determination of total 25-hydroxyvitamin D. Roche Diagnostics International Ltd., Rotkreuz, Switzerland, 2012.

Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:53–8.

Wood S . Modelling and smoothing parameter estimation with multiple quadratic penalties. J R Stat Soc B 2000;62:413–28.

Mangin M, Sinha R, Fincher K . Inflammation and vitamin D: the infection connection. Inflamm Res 2014;63:803–19.

Haugen J, Chandyo RK, Ulak M et al. 25-Hydroxy-Vitamin D Concentration Is Not Affected by Severe or Non-Severe Pneumonia, or Inflammation, in Young Children. Nutrients 2017: 9 52.

Rhedin S, Lindstrand A, Rotzen-Ostlund M et al. Clinical utility of PCR for common viruses in acute respiratory illness. Pediatrics 2014;133:e538–45.

Pavia AT . Viral infections of the lower respiratory tract: old viruses, new viruses, and the role of diagnosis. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52 (Suppl 4): S284–9.

Haugen J, Ulak M, Chandyo RK et al. Low prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency among Nepalese infants despite high prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency among their mothers. Nutrients 2016;8:825.

Schulze KJ, Christian P, Wu LS et al. Micronutrient deficiencies are common in 6- to 8-year-old children of rural Nepal, with prevalence estimates modestly affected by inflammation. J Nutr 2014;144:979–87.

Bhandari S . Micronutrients deficiency, a hidden hunger in Nepal: prevalence, causes, consequences, and solutions. Int Sch Res Notices 2014;2015:276469.

Hoogenboezem T, Degenhart HJ, de Muinck Keizer-Schrama SM et al. Vitamin D metabolism in breast-fed infants and their mothers. Pediatr Res 1989;25:623–8.

Dawodu A, Tsang RC . Maternal vitamin D status: effect on milk vitamin D content and vitamin D status of breastfeeding infants. Adv Nutr 2012;3:353–61.

Hollis BW, Wagner CL, Howard CR et al. Maternal versus infant vitamin D supplementation during lactation: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 2015;136:625–34.

Ulak M, Chandyo RK, Thorne-Lyman AL, Henjum S et al. Vitamin status among breastfed infants in Bhaktapur, Nepal. Nutrients 2016;8:149.

Abdel-Wareth L, Haq A, Turner A et al. Total vitamin D assay comparison of the Roche Diagnostics "Vitamin D total" electrochemiluminescence protein binding assay with the Chromsystems HPLC method in a population with both D2 and D3 forms of vitamin D. Nutrients 2013;5:971–80.

Singh RJ, Taylor RL, Reddy GS, Grebe SK . C-3 epimers can account for a significant proportion of total circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D in infants, complicating accurate measurement and interpretation of vitamin D status. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:3055–61.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the children and their families for participating in this study and the staff at the Child Health Research Project, Department of Child Health, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Statement of Financial Support

The funders of the project were the European Commission (EU-INCO-DC contract number INCO-FP6-003740), the Meltzer Foundation in Bergen, Norway, South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority (grant number: 2012090), and Innlandet Hospital Trust, Norway (grant number 150263).

Supplementary material is linked to the online version of the paper at

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Haugen, J., Basnet, S., Hardang, I. et al. Vitamin D status is associated with treatment failure and duration of illness in Nepalese children with severe pneumonia. Pediatr Res 82, 986–993 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2017.71

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2017.71