Abstract

Purpose of this review is to deal with priorities and strategies to significantly tackle inequalities in the management of pediatric diseases in low–middle-income countries. This issue has become a focal point of epidemiological and public health, with special reference to chronic nontransmissible diseases. We will provide our readership with an essential overview of the cultural, institutional, and political events, which have occurred over the last 20 y and which have produced the current general framework for epidemiology and public health. Then the most recent epidemiological data will be evaluated, in order to quantify the interaction between the medical components of the disease profiles and their socioeconomic determinants. Finally, a focus will be added on models of pediatric chronic kidney diseases, which are in our opinion amongst the most sensitive markers of the interplay between health and society. Collaborative, pediatrician-initiated, multicentre projects in these fields should be given priority in calls for grants supported by public agencies. The involvement of a critical mass of those working in the “fringes” of pediatric care is a final, essential mean by which significant results can be produced under the sole responsibility and research interest of centers of excellence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The main purpose of this review is to attempt to answer an ever more relevant question: Which priorities and strategies could and should be adopted by pediatricians in order to significantly tackle inequality and inequity in the management of pediatric diseases in low–middle-income countries. This issue has become a focal point of epidemiological and public health, due to the many unmet needs and rights of pediatric populations worldwide with special reference to chronic non transmissible diseases (1,2).

The focus here is not, therefore, on providing a further detailed review of what has and is still being published on this subject. Instead, with an eye to the future, we outline the development of some suggestions which hinge on the following three steps:

-

(i) An essential overview of the cultural, institutional and political events which have occurred over the last 20 y and which have produced the current general framework for epidemiology and public health;

-

(ii) A brief evaluation of the epidemiological data which have been accumulating mainly over the last 10 y, in order to quantify and qualify the interaction between the strictly medical components of the disease profiles and their socioeconomic, cultural, and institutional determinants;

-

(iii) A focus on model scenarios of pediatric chronic diseases, specifically chronic kidney disease, which are the most sensitive markers of the interplay between health and society.

General Framework

“The last two decades have brought revolutionary changes in global health…”: an important paper summarizes the radical impact of the globalization process (3). Being principally driven by economic, institutional, and political actors and variables, globalization has transformed the role, the terms of reference, and the perspectives of the world of health. Table 1 shows a synoptic and chronological view of the key events.

The report on the global burden of diseases (GBD) from the mid-nineties closely followed the World Bank reports, which declared that health systems had become economically too important and societally too critical to be left exclusively in the hands of a specialized agency such as the World Health Organization. In parallel with this important evolution of the epidemiological approach to health planning, in the early ‘90 the creation of the World Trade Organization represented the institutional expression of the directed impact of trade criteria and agencies in the area of services delivery. The economic and technological components of health should be regulated according to norms, which are independent from those which govern the relationships between individuals and peoples, such as, at country level, the competences of national governments and of their constitutions.

The highly conflicting Doha clause, which recognized that public health interests could justify exceptions to the World Trade Organization rules with respect to patents, must be accountable to the World Trade Organization tribunal (4,5).

The GBD-based epidemiology became instrumental in mapping the health needs, which were then adopted by the Millennium Development Goals. Goals which are failing, however, to fulfill the promises with appropriate investments. This gap between commitment and reality coincides closely with the economic-income profiles of the countries and therefore with their capacity to provide health coverage. The massive private involvement in the health sector, either in the name of solidarity, or as a public-private-partnership has become a highly ambivalent protagonist of global scenarios, as it makes the absence of national health plans and commitments appear “sustainable” in some low–middle-income countries (6,7,8).

The publication of the final report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health (9), which formally underlines the dominant role played by socioeconomic conditions in causing diseases, as well as their nonsustainable burden, coincides with the explosion of the financial crisis, the implications of which, in terms of the dramatic and global increase in inequalities, are too well known and well documented to be further underlined here (10).

In this scenario, the causes and the implications of the partial but significant failures of the Millennium Development Goals have become clear, as well as the methodological limitations and flaws of the GBD representation of the health status of the world. A brand new and importantly revised series of reports from the core group(s), who are the protagonists of the global epidemiological accountability on health, provide the informative support for the two most recent developments in the scenarios in Table 1 :

-

The “discovery” certified and adopted by the UN that nontransmissible chronic diseases play a dominant global role, both from the point of view of their epidemiological relevance and the challenge they impose on the availability of strategic (institutional, even more than economic) resources to allocate specifically in low–middle-income countries (11);

-

The accentuation and the generalization of the debates on what should be a generally valid formula (Universal health coverage) is the most recognized acronym to be adopted globally to assume sustainability to the new development goals (12).

The Epidemiological Scenarios

Materials and Methods

According to the general objectives of the review, rather strict criteria have been adopted for the selection of the pertinent literature.

Against the general framework provided by few very recently published major documents and studies (leaving aside reports of public or private actors and agencies), search and retrieval were restricted to:

-

Studies with a partial focus, at least, on pediatric age problems and diseases;

-

The specific mention, in the title and/or in the text, of the key terms defining sociodeterminants of health/diseases, with a special attention given to inequality/ies and inequity/ies;

-

Reports with data not only from global statistics, but from individual countries, were scrutinized;

-

Only a few of the most representative studies covering high-income countries were selected, while all studies coming from low-middle income countries were considered;

-

Because of the specific competence and the direct involvement of the authors, pediatric chronic kidney diseases were selected as a suitable model of noncommunicable chronic diseases.

The operational definitions of the variables explored in the review are as follows:

-

Inequality: through socioeconomic indicators, it defines the distribution of a population into various strata (mostly quintiles), which assign individuals to a better off (quintile 1) or progressively unfavorable status (quintile 5);

-

Inequity: corresponds most directly to a value definition, as it describes how resources and accessibility to goods which are fundamental rights (e.g., health care) are distributed in a population, according to the criteria which try to bridge (or worsen) the gaps documented in the inequality quintiles.

The General Framework

Four reports (13,14,15,16) have been chosen as highly representative of the enormous amount of data, models, propositions, and controversies produced mainly over the last 3 y in order to accompany, provoke, and discuss the transition into what is called the post-2015 era, with its most likely Sustainable Development Goals.

The report by the GBD groups (13) on the evolution of pediatric mortality in the populations ≤ 5 y of age in 188 countries between 1990–2013 deserves priority not only for the unique richness of its data, but because of the key methodological and public health messages which are provided:

-

Information sources to describe and compare pediatric populations have become progressively more reliable to allow for useful comparisons, across homogeneous groups of populations;

-

The historical trends are globally suggestive of a possible positive progress, but the enormous variability of mortality data between countries foresees that country-specific and targeted programs should be developed;

-

This need is even more important if well qualified and group-attributable socioeconomic conditions are taken into account, besides data on education and income levels which define the quintiles;

-

The noncommunicable diseases appear increasingly important also in low–middle-income countries and are preferred targets for improvements.

The second paper proposed for its general methodological implications (14) is about adult populations, but introduces two issues which are certainly critical for pediatric chronic diseases. The collection and critical analysis of epidemiological data must aim:

-

Firstly, not solely nor principally at describing the past-present situation but at making prospectively documented deductions for a defined future;

-

Secondly, at adopting “avoidability”, in the planning of public health research, which would meet the challenges of inequality, inequity, sustainability, central to this report.

It is necessary to highlight how the authoritative groups who sign the report strongly underline the dramatic scarcity of field and country-based studies, where both medical and nonmedical variables are prospectively collected. This would allow for a truly informative evaluation of chronic conditions, which are by definition highly dependent on factors strictly linked to inequality/inequity, such as accessibility to care, living conditions, or the daily experiences of vulnerable groups.

The other two papers (15,16) must be quoted here not only because of their scientific-policy weight, but because they illustrate in great detail the connections and the concrete implications of the frameworks where epidemiological data must be placed to provide its full informative content, and to guide effective planning and research choices.

Epidemiological Reports Focused on Inequality/ies/Inequity/ies in Pediatric Populations

The material pertinent to our theme has been grouped with the purpose of documenting:

-

The degree and quality of data availability in international reports;

-

The specific profile of “regional” reports on the health status of children, respectively in low income countries, in Brazil and China, as examples of emerging national economies and in model high-income countries.

In view of the substantial comparability of the approach adopted in the studies (mostly epidemiological elaborations on administrative data sources), as well as of the consistency of the results, the presentation of the data is concentrated in the essential data summarized in the Tables, with broader comments in the Discussion section.

Only six reports ( Table 2 ) have been found, over a period of 8 y, which have explored the relationship between the mortality data and nonmedical determinants (with the exception of the national survey reported by Barros et al. (17), which describes the distribution of interventions across quintiles). The consistent finding that mothers’ education weighs as much as (or more) than estimates of income (based on mean country data) mirrors the data available for the management of acute diseases. None of the studies allows for the specific quali-quantification of the care and mortality burden attributable to chronic diseases.

The epidemiological profiles found for individual low-income countries ( Tables 3 and 4 ) are mostly from sub-Saharan African countries ( Table 3 ).

The model case of Bangladesh ( Table 4 ) is of specific interest because of the results of interventions aimed at correcting (with encouraging results) the inequity component of care, in a country otherwise known for dramatic structural inequalities.

The case of Vietnam (18) ( Table 4 ) appears also puzzling and worrying. Officially no longer a low-income country, with development indicators which are highly promising and a “history” of national solidarity, it is facing the widening of an inequity gap in terms of maternal health care utilization, which is specifically evident against ethnic and vulnerable groups.

Field and ad hoc studies are essential in these countries, both to surrogate the unavailability of reliable administrative data sources, and to explore the heterogeneous and complex spectrum of the factors which cause and maintain inequality/inequity and make sustainability a pure play of chance.

The few country-centred reports confirm the main GBD and other international reports in underlying that the positive global trends are far from being applicable to all countries, where improving or worsening outcomes are intertwined with the instability of the general country conditions.

Brazil ( Table 5 ) could certainly be considered a special and significant case, as there is a long series of reports documenting the difficulty of intervening to overcome gaps in inequalities and inequities measured in health. As a whole, Brazil remains one of the countries with extreme and polarized levels of inequality, with extensive exclusion of fragile populations.

The only report available so far from a country like China (19), which has been the protagonist of dramatic and rapidly evolving socioeconomic transformations, is consistent with the expectations for a country which has taken decisions almost exclusively motivated by and compatible with economic considerations and measures.

The problem of the dramatic exacerbation of inequality/inequities also in high-income countries following the emergence of the crisis, has been documented in so many national, regional, global reports not to need specific quotations. The few studies listed in Table 6 are the results of a selection meant simply to give an idea of the degree of consistency of the findings across the spectrum of the health systems; with the exception of Sweden (where the problem is rather restricted and specific), all countries document and recognize also in such sensitive areas like the mother–child health, the risk (and the practice) of further marginalization of the already fragile populations, through the variety of obstacles imposed to their right of accessibility to care.

Overall, the substantial absence of well-conducted and representative studies focusing specifically on the documentation of how the inequalities and inequities impact the quality of care and the outcome of chronic diseases is somehow surprising.

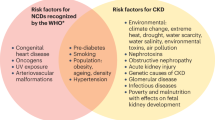

The Scenario of Pediatric/Chronic Renal Diseases

The sequence of presentation of data is reversed in this section, to reflect the substantial epidemiological invisibility in low–middle-income countries of pediatric chronic conditions, and among them of the model condition of chronic kidney disease.

The reference framework is provided ( Table 7 ) by data published over the last few years in high-income countries, which is difficult to compare because of the quali-quantitative heterogeneity of the populations, as well of the study designs and instruments: from ad hoc registries, to databases with uncertain representativeness, to surveys, to larger–smaller cohorts. The main message is clear: populations which are already fragile because of their ethnic or socioeconomic conditions are also discriminated against in terms of their accessibility to chronic kidney disease treatment. It is interesting to note that the impact of such discrimination on the quali-quantitative outcomes (from burden of the disease to mortality) is not a direct explicit concern. Neither the issues of “avoidability” nor of targeted interventions receive consideration. The data in Table 7 documents well the role of kidney diseases as a model of the degree and the implications of the invisibility of chronic pediatric diseases in low–middle-income countries as it is exemplified by chronic kidney diseases. The information available is patchy, the designs of the studies and the quality of the data are hardly controlled, and the data on discrimination are roughly presented, but hardly explored with respect to avoidable causes.

The mention of a prospective well-documented cohort in Nicaragua (detailed results and comments are in their publication phase) is meant mainly to reiterate that a chronic pediatric condition must be allowed to become visible with the specificity of the related unmet needs, risk conditions and outcomes in order to produce even minimally reliable data.

Discussion and Conclusions

It is widely accepted that the area of maternal and child health is the first, most critical, and most sensitive instrument in measuring the unmet needs and their changes, for better or for worse, of societies. The consistent findings of the review are summarized as follows:

-

(i) The economic indicators of inequalities are definitely important variables, but they fail to quantify-qualify adequately the gradients of health conditions existing across extremes. The socio cultural-educational context of the mother is a far more precise descriptive and prognostic marker.

-

(ii) The variation in country policies in terms of healthcare investments is another factor of primary importance, which could aid in determining whether and to what extent the impact of inequalities could be reasonably corrected in terms of equity. The increasingly wider use of this term in policy plans and in bioethical discourses is not matched, in practice, by substantial interventions.

-

(iii) The interplaying gaps between inequalities and inequities are very similar in their mechanisms and evaluations across the spectrum of low–high-income countries, beyond the obvious differences in terms of baseline levels of socioeconomic indicators and resources.

-

(iv) Chronic pediatric conditions have been shown to be exposed to the additional severe risk of epidemiological invisibility, causing them to remain in an orphan status with respect to their need for introduction into health care systems, despite, or because of, their related burden.

-

(v) The case of the chronic kidney diseases, which has been explored as a model condition, is by no means alone. The wide and orphan range of disabilities is certainly a further priority (20), but other chronic pediatric disorders, from cancer to rheumatic diseases, are now seen as essential components of health care, also in many deprived countries (21,22).

Substantial and original investment in pediatric research in low-income countries and in middle-income countries should not produce basic research as seen in in western countries, rather it should be used to plan and develop projects, conceived and implemented as advanced research programs of the transferability of care strategies. Breaking away from their role as “death events” or indicators of disease burdens, children with chronic conditions should become visible as real histories, which are systematically translated into pragmatic prospective “cohort studies”. The inclusion criteria for patients in clinical research projects must include, with the same level of importance, essential medical information as well as information regarding nonmedical variables, which are necessary to qualify the chronic histories of children in terms of inequality and inequity. Simple, well-planned translational research projects targeted to chronic childhood diseases should be a priority for pediatric teams, with the active presence of nonmedical actors as well as of the families of the children, in order to assure continuity of care.

Inequality/ies and inequity/ies should become part of the care programs as comorbid conditions, with a decisional weight similar to that generated by a genetic/biochemical test, which modifies a specific risk profile of a child within a diagnostically homogeneous group.

The need for this translational approach must be faced with a flexibility-creativity of methods to be adapted to the expected variability of the settings of life and care. Accordingly, pediatric research should contribute through field projects which tackle the real epidemiology of the communities where inequalities and in-equity are a permanent comorbid condition. The often underlined insufficient responsiveness and/or compliance to purely medical interventions needs to be reversed into projects where collaborative, targeted, nonoccasional interventions are planned, and implemented nonmedical actors and strategies are activated.

Scientific-professional societies play a critical role, by fostering this integrated approach to chronic diseases. A post-2015 agenda must include chronic pediatric conditions as a measure of a concrete commitment to the contribution to the promotion of equity. Maps of priorities in different regions and countries should stimulate and accelerate implementation strategies.

Collaborative, pediatrician-initiated, multicentre (national, regional, international) projects in this field should be given priority in calls for medium–long-term research grants supported by public agencies, in order to integrate and balance the impact of ongoing trends which favor private initiatives. Initiatives which, by definition, carry the unfortunately risk of maintaining nonequitable policies of care.

The Sustainable Development Goals agenda (whose definition is still in progress) should be considered an important opportunity to facilitate and expand the approach to pediatric chronic diseases, representing a difficult but progressively successful cultural investment devoted to disease-related conditions in the youngest age groups.

The involvement of a critical mass of those working in the “fringes” of pediatric care is a final, essential means by which significant results can be produced; this cannot be the sole responsibility and research interest of centers of excellence.

The “evidence” supporting a choice in this direction is there. At the end of the day, pediatric research should become a protagonist even in making such evidence accessible to our future generations, who are so easily and equally marginalized in real economic and political terms.

Statement of Financial Support

No financial assistance was received to support this study. No financial ties to declare.

References

Lawn JE. The child survival revolution: what next? Lancet 2014;384:931–3.

Stiglitz J. The price of inequality.Penguin Book: New York, 2012. pp. 592.

Gostin LO, Sridhar D. Global health and the law. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1732–40.

World Bank. Global Economic Prospects: Commodities at the Crossroads. World Bank: Washington, DC 2009.

‘t Hoen EFM. The Global Politics of Pharmaceutical Monopoly Power Drug Patents, Access, Innovation and the Application of the WTO Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health. AA Diemen, The Netherlands: AMB Diemen, 2009.

Schultz M, Rockström J, Öhman MC, Cornell S, Persson A, Norström A. Human Prosperity Requires Global Sustainability – A Contribution to the Post-2015 Agenda and the Development of Sustainable Development Goals. A Stockholm Resilience Centre Report to the Swedish Government Office. Stockholm, 2013.

Carrera C, Azrack A, Begkoyian G, et al.; UNICEF Equity in Child Survival, Health and Nutrition Analysis Team. The comparative cost-effectiveness of an equity-focused approach to child survival, health, and nutrition: a modelling approach. Lancet 2012;380:1341–51.

Frenk J, Gómez-Dantés O, Moon S. From sovereignty to solidarity: a renewed concept of global health for an era of complex interdependence. Lancet 2014;383:94–7.

Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final report. Geneva: World Health Organization 2008.

Marmot MG, Bell R. How will the financial crisis affect health? BMJ 2009;338:b1314.

Bollyky TJ, Emanuel EJ, Goosby EP, Satcher D, Shalala DE, Thompson TG. NCDs and an outcome-based approach to global health. Lancet 2014;384:2003–4.

Vega J. Universal health coverage: the post-2015 development agenda. Lancet 2013;381:179–80.

Wang H, Liddell CA, Coates MM, et al. Global, regional, and national levels of neonatal, infant, and under-5 mortality during 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014;384:957–79.

Norheim OF, Jha P, Admasu K, et al. Avoiding 40% of the premature deaths in each country, 2010-30: review of national mortality trends to help quantify the UN sustainable development goal for health. Lancet 2015;385:239–52.

Ottersen OP, Dasgupta J, Blouin C, et al. The political origins of health inequity: prospects for change. Lancet 2014;383:630–67.

Stenberg K, Axelson H, Sheehan P, et al.; Study Group for the Global Investment Framework for Women’s Children’s Health. Advancing social and economic development by investing in women’s and children’s health: a new Global Investment Framework. Lancet 2014;383:1333–54.

Barros AJ, Ronsmans C, Axelson H, et al. Equity in maternal, newborn, and child health interventions in Countdown to 2015: a retrospective review of survey data from 54 countries. Lancet 2012;379:1225–33.

Målqvist M, Lincetto O, Du NH, Burgess C, Hoa DT. Maternal health care utilization in Viet Nam: increasing ethnic inequity. Bull World Health Organ 2013;91:254–61.

Fu R, Wang Y, Bao H, et al. Trend of urban-rural disparities in hospital admissions and medical expenditure in China from 2003 to 2011. PLoS One 2014;9:e108571.

Editorial. Children with disabilities–invisible no more. Lancet 2013;381:1877.

Gupta S, Rivera-Luna R, Ribeiro RC, Howard SC. Pediatric oncology as the next global child health priority: the need for national childhood cancer strategies in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001656.

Barr RD, Antillón Klussmann F, Baez F, et al. Asociación de Hemato-Oncología Pediátrica de Centro América (AHOPCA): a model for sustainable development in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2014;61:345–54.

Countdown 2008 Equity Analysis Group. Mind the gap: equity and trends in coverage of maternal, newborn, and child health services in 54 Countdown countries. Lancet 2008; 371: 1259–1267.

Lykens K, Singh KP, Ndukwe E, Bae S. Social, economic, and political factors in progress towards improving child survival in developing nations. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2009;20(4 Suppl):137–48.

Gakidou E, Cowling K, Lozano R, Murray CJ. Increased educational attainment and its effect on child mortality in 175 countries between 1970 and 2009: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2010;376:959–74.

Requejo JH, Bryce J, Barros AJ, et al. Countdown to 2015 and beyond: fulfilling the health agenda for women and children. Lancet 2015;385:466–76.

Zere E, Moeti M, Kirigia J, Mwase T, Kataika E. Equity in health and healthcare in Malawi: analysis of trends. BMC Public Health 2007;7:78.

Zere E, Kirigia JM, Duale S, Akazili J. Inequities in maternal and child health outcomes and interventions in Ghana. BMC Public Health 2012;12:252.

Gram L, Soremekun S, ten Asbroek A, et al. Socio-economic determinants and inequities in coverage and timeliness of early childhood immunisation in rural Ghana. Trop Med Int Health 2014;19:802–11.

Babirye JN, Engebretsen IM, Makumbi F, et al. Timeliness of childhood vaccinations in Kampala Uganda: a community-based cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2012;7:e35432.

Okoronkwo IL, Onwujekwe OE, Ani FO. The long walk to universal health coverage: patterns of inequities in the use of primary healthcare services in Enugu, Southeast Nigeria. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:132.

Adams AM, Ahmed T, El Arifeen S, Evans TG, Huda T, Reichenbach L ; Lancet Bangladesh Team. Innovation for universal health coverage in Bangladesh: a call to action. Lancet 2013;382:2104–11.

Quayyum Z, Khan MN, Quayyum T, Nasreen HE, Chowdhury M, Ensor T. “Can community level interventions have an impact on equity and utilization of maternal health care” - evidence from rural Bangladesh. Int J Equity Health 2013;12:22.

Victora CG, Vaughan JP, Barros FC, Silva AC, Tomasi E. Explaining trends in inequities: evidence from Brazilian child health studies. Lancet 2000;356:1093–8.

Landmann Szwarcwald C, Lourenco Tavares de Andrade C, Bastos FI. Income inequality, residential poverty clustering and infant mortality: a study in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Soc Sci Med 2002; 55: 2083–2092.

Messias E. Income inequality, illiteracy rate, and life expectancy in Brazil. Am J Public Health 2003;93:1294–6.

Aquino R, de Oliveira NF, Barreto ML. Impact of the family health program on infant mortality in Brazilian municipalities. Am J Public Health 2009;99:87–93.

Rasella D, Aquino R, Barreto ML. Reducing childhood mortality from diarrhea and lower respiratory tract infections in Brazil. Pediatrics 2010;126:e534–40.

Sousa A, Hill K, Dal Poz MR. Sub-national assessment of inequality trends in neonatal and child mortality in Brazil. Int J Equity Health 2010;9:21.

Rasella D, Aquino R, Santos CA, Paes-Sousa R, Barreto ML. Effect of a conditional cash transfer programme on childhood mortality: a nationwide analysis of Brazilian municipalities. Lancet 2013;382:57–64.

Rasella D, Aquino R, Barreto ML. Impact of income inequality on life expectancy in a highly unequal developing country: the case of Brazil. J Epidemiol Community Health 2013;67:661–6.

Garcia-Subirats I, Vargas I, Mogollón-Pérez AS, et al. Inequities in access to health care in different health systems: a study in municipalities of central Colombia and north-eastern Brazil. Int J Equity Health 2014;13:10.

Flores G, Olson L, Tomany-Korman SC. Racial and ethnic disparities in early childhood health and health care. Pediatrics 2005;115:e183–93.

Sims M, Sims TL, Bruce MA. Urban poverty and infant mortality rate disparities. J Natl Med Assoc 2007;99:349–56.

Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Williams DR, Pamuk E. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: what the patterns tell us. Am J Public Health 2010;100 Suppl 1:S186–96.

Walker LO, Chesnut LW. Identifying health disparities and social inequities affecting childbearing women and infants. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2010;39:328–38.

Lau M, Lin H, Flores G. Racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care among US adolescents. HSR 2012;47:2031–59.

Weightman AL, Morgan HE, Shepherd M, Kitcher H, Roberts C, Dunstan FD. Social inequality and infant health in the UK: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000964.

Viner RM, Hargreaves DS, Coffey C, Patton GC, Wolfe I. Deaths in young people aged 0–24 years in the UK compared with the EU15+ countries, 1970–2008: analysis of the WHO Mortality Database. Lancet 2014;382:880–92.

Sidebotham P, Fraser J, Fleming P, Ward-Platt M, Hain R. Child death in high-income countries 2. Patterns of child death in England and Wales. Lancet 2014;384:904–14.

Mills C, Reid P, Vaithianathan R. The cost of child health inequalities in Aotearoa New Zealand: a preliminary scoping study. BMC Public Health 2012;12:384.

Butler DC, Thurecht L, Brown L, Konings P. Social exclusion, deprivation and child health: a spatial analysis of ambulatory care sensitive conditions in children aged 0-4 years in Victoria, Australia. Soc Sci Med 2013;94:9–16.

Wallby T, Hjern A. Child health care uptake among low-income and immigrant families in a Swedish county. Acta Paediatr 2011;100:1495–503.

Harambat J, van Stralen KJ, Schaefer F, et al. Disparities in policies, practices and rates of pediatric kidney transplantation in Europe. Am J Transplant 2013;13:2066–74.

Harambat J, van Stralen KJ, Verrina E, Groothoff JW, Schaefer F, Jager KJ ; ESPN/ERA-EDTA Registry. Likelihood of children with end-stage kidney disease in Europe to live with a functioning kidney transplant is mainly explained by nonmedical factors. Pediatr Nephrol 2014;29:453–9.

Chesnaye NC, Schaefer F, Groothoff JW, et al. Disparities in treatment rates of paediatric end-stage renal disease across Europe: insights from the ESPN/ERA-EDTA registry. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015;30:1377–85.

Patzer RE, Amaral S, Klein M, et al. Racial disparities in pediatric access to kidney transplantation: does socioeconomic status play a role? Am J Transplant 2012;12:369–78.

Patzer RE, Sayed BA, Kutner N, McClellan WM, Amaral S. Racial and ethnic differences in pediatric access to preemptive kidney transplantation in the United States. Am J Transplant 2013;13:1769–81.

Amaral S, Patzer R. Disparities, race/ethnicity and access to pediatric kidney transplantation. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2013;22:336–43.

Samuel SM, Foster BJ, Tonelli MA, et al.; Pediatric Renal Outcomes Canada Group. Dialysis and transplantation among Aboriginal children with kidney failure. CMAJ 2011;183:E665–72.

Grace BS, Kennedy SE, Clayton PA, McDonald SP. Racial disparities in paediatric kidney transplantation. Pediatr Nephrol 2014;29:125–32.

Schoenmaker NJ, Tromp WF, van der Lee JH, et al. Disparities in dialysis treatment and outcomes for Dutch and Belgian children with immigrant parents. Pediatr Nephrol 2012;27:1369–79.

Gheissari A, Hemmatzadeh S, Merrikhi A, Fadaei Tehrani S, Madihi Y. Chronic kidney disease in children: A report from a tertiary care center over 11 years. J Nephropathol 2012;1:177–82.

Cerón A, Fort MP, Morine CM, Lou-Meda R. Chronic kidney disease among children in Guatemala. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2014;36:376–82.

Odetunde OI, Okafor HU, Uwaezuoke SN, Ezeonwu BU, Ukoha OM. Renal replacement therapy in children in the developing world: challenges and outcome in a tertiary hospital in southeast Nigeria. ScientificWorldJournal 2014;2014:903151.

Souilmi FZ, Sqalli Houssaini T, EL Bardai G, Kabbali N, Arrayhani M, Hida M. The fate of patients who started hemodialysis during childhood or adolescence: results of an Interregional Moroccan Survey. International Scholarly Research Notices 2014;2014:4 pages: Article ID 389729.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sereni, F., Edefonti, A., Lepore, M. et al. Social and economic determinants of pediatric health inequalities: the model of chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Res 79, 159–168 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2015.194

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2015.194

This article is cited by

-

Policy in pediatric nephrology: successes, failures, and the impact on disparities

Pediatric Nephrology (2021)

-

The two extremes meet: pediatricians, geriatricians and the life-course approach

Pediatric Research (2019)