Abstract

The fossil record of crocodylians and their relatives (pseudosuchians) reveals a rich evolutionary history, prompting questions about causes of long-term decline to their present-day low biodiversity. We analyse climatic drivers of subsampled pseudosuchian biodiversity over their 250 million year history, using a comprehensive new data set. Biodiversity and environmental changes correlate strongly, with long-term decline of terrestrial taxa driven by decreasing temperatures in northern temperate regions, and biodiversity decreases at lower latitudes matching patterns of increasing aridification. However, there is no relationship between temperature and biodiversity for marine pseudosuchians, with sea-level change and post-extinction opportunism demonstrated to be more important drivers. A ‘modern-type’ latitudinal biodiversity gradient might have existed throughout pseudosuchian history, and range expansion towards the poles occurred during warm intervals. Although their fossil record suggests that current global warming might promote long-term increases in crocodylian biodiversity and geographic range, the 'balancing forces' of anthropogenic environmental degradation complicate future predictions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ongoing climate change, with projected global warming of 2.0–4.8°C over the next century1, could have profound repercussions for crocodylian distributions and biodiversity. As ectotherms, living crocodylians are environmentally sensitive2, and 10 of the 23 extant species are at high extinction risk (http://www.iucncsg.org/;2015). Ecological models can predict the responses of extant species distributions to rising temperatures. However, only the fossil record provides empirical evidence of the long-term interactions between climate and biodiversity3, including during intervals of rapid climate change that are potentially analogous with the present4.

Pseudosuchia is a major reptile clade that includes all archosaurs closer to crocodylians than birds, and made its first fossil appearance nearly 250 million years ago, at the time of the crocodile–bird split5. Crocodylians, the only extant pseudosuchians, are semi-aquatic predators with low morphological diversity, and a tropically restricted geographic range (a band of ∼35° either side of the Equator)6. Although often regarded as ‘living fossils’, the pseudosuchian fossil record reveals a much richer evolutionary history and high ancient biodiversity. This poses a key question about the drivers of long-term evolutionary decline in groups that were highly diverse in the geological past, especially given the extraordinary high biodiversity (∼10,000 species) of the only other extant group of archosaurs, birds7. Over 500 extinct pseudosuchian species are known (this study), with a broader latitudinal distribution6 and a wider array of terrestrial ecologies than their living counterparts8,9. Several diverse lineages also independently invaded marine environments10. Body plans and feeding modes showed much higher diversity, including flippered taxa and herbivorous forms10,11,12,13, and body sizes varied from dwarfed species <1 m in length14, to giants such as Sarcosuchus, which reached around 12 m in length and weighed up to 8 metric tons15. Climate has often been proposed to have shaped pseudosuchian biodiversity through time6,8,16, and the group’s geographic distribution over the past 100 million years has been used as evidence in palaeoclimatic reconstructions2.

Here we examine the effect of climate on spatiotemporal patterns in pseudosuchian biodiversity over their 250 million year history, using a comprehensive fossil occurrence data set. Our study is the first to analyse climatic drivers of pseudosuchian biodiversity through the group’s entire evolutionary history, applying rigorous quantitative approaches to ameliorate for uneven sampling across both time and space. Furthermore, this is the only comprehensive, temporally continuous fossil occurrence dataset for a major extant vertebrate group: equivalent datasets are not currently available for mammals, birds, squamates, teleosts, or other groups with evolutionary histories of similar durations.

Results and discussion

The fossil record at face value

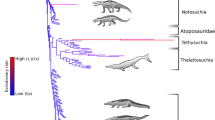

An uncorrected global census of pseudosuchian genera (Fig. 1; and species, Supplementary Fig. 1) shows an apparent trend of increasing biodiversity through the Mesozoic, punctuated by a latest Triassic crash, a severe decline across the Jurassic/Cretaceous (J/K) boundary and the Cretaceous/Paleogene (K/Pg) mass extinction, from which recovery only started in the early Neogene. However, application of sampling standardisation reveals a different and more nuanced story (Fig. 2).

Red line represents non-marine taxa and the blue line represents marine taxa. Silhouettes of representative pseudosuchians are modified from work by Dmitry Bogdan, Evan Boucher, Scott Hartman, Mike Keesey, Nobumichi Tamura (hosted at: http://phylopic.org, where all license information is available).

(a) Non-marine biodiversity within continental regions for a subsampling quorum level of 0.4, and palaeotemperature (δ18O) curve for the last ∼70 Myr ago17 (with weighted means (yellow circles)). (b) Global marine biodiversity for a subsampling quorum level of 0.4 (blue circles) and sea level curve18 (with weighted means (yellow circles)). Adamantina, Adamantina Formation subsampled crocodylomorph biodiversity; EECO, Early Eocene Climatic Optimum; MECO, Mid-Eocene Climatic Optimum; MMCO, Mid-Miocene Climatic Optimum; PETM, Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. Linear regression for pooled regional subsampling results on geological age in millions of years: log10 subsampled genera=0.0015 × age+0.244 (P=0.002; N=38; R2=0.221).

Biodiversity in the early Mesozoic

Subsampled pseudosuchian biodiversity reached a peak during the earliest intervals of the group’s history and shows a long-term pattern of gradual decline towards the present day (Fig. 2). Substantial short-term volatility around this trend, indicated by a low coefficient of determination (linear regression: N=38, R2=0.221; Fig. 2), suggests that this overall pattern was punctuated by the extinctions and radiations of individual clades (see below). Nevertheless, for much of the Triassic, non-marine pseudosuchian biodiversity exceeded that of nearly all later time intervals (Fig. 2a), indicating exceptionally rapid early diversification19. We also find evidence for a strong palaeotropical biodiversity peak during the Late Triassic (Fig. 3a,b), similar to the modern-day latitudinal biodiversity gradient20.

(a) Triassic–early Late Cretaceous (K6) subsampled biodiversity versus palaeolatitudinal centroid. (b) Late Triassic (Tr4) log10-transformed subsampling curves. (c) Late Cretaceous (K7 and K8) subsampled biodiversity versus palaeolatitudinal centroid. (d) Paleogene subsampled biodiversity versus palaeolatitudinal centroid. (e) Neogene subsampled biodiversity versus palaeolatitudinal centroid. (f) Early Neogene (Ng1) log10-transformed subsampling curves. (g) Middle Neogene (Ng2) log10-transformed subsampling curves. Dashed arrows denote notable changes in biodiversity between consecutive time intervals within a single continental region. K, Cretaceous; Ng, Neogene; Tr, Triassic.

Only the crocodylomorph clade survived the Triassic/Jurassic mass extinction (201 Myr ago)5. During the Jurassic, non-marine crocodylomorph biodiversity remained depressed relative to the Triassic pseudosuchian peak (Fig. 2a). However, the group radiated into new morphospace21, and thalattosuchian crocodylomorphs invaded the marine realm by the late Early Jurassic10,12. Subsequently, marine crocodylomorph biodiversity increased until at least the Late Jurassic16 (Fig. 2b), tracking a general trend of rising eustatic sea levels22. The earliest Cretaceous fossil record is considerably less informative than those of many other intervals23. However, our subsampled estimates are congruent with observations of phylogenetic lineage survival16,24,25, and indicate that both marine and non-marine crocodylomorph biodiversity declined across the J/K boundary (Figs 2 and 3a), including the extinction of teleosauroid thalattosuchians16,25.

Sampling of palaeotropical non-marine crocodylomorphs is limited throughout the Jurassic–Cretaceous (Figs 3a and 4a). However, good sampling of terrestrial early Late Cretaceous North African crocodylomorphs inhabiting a low-latitude (18°N), semi-arid biome8,14 (Fig. 4b) indicates subsampled biodiversity levels comparable to those of palaeotemperate regions in other Cretaceous time slices (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, sub-palaeotropical (24–28°S) South American crocodylomorphs of the Late Cretaceous Adamantina Formation were exceptionally diverse8,26, raising the possibility that pseudosuchians in fact reached their highest biodiversities in tropical environments during the mid-Cretaceous greenhouse world. In contrast to previous work6, this suggests that there was no palaeotropical trough in Cretaceous crocodylomorph biodiversity, differing from the pattern recovered for contemporaneous dinosaurs27. Previous work on both crocodylomorphs6 and dinosaurs27 found low palaeotropical biodiversity by effectively ‘averaging’ global biodiversity across palaeolatitudinal bands, applying sampling standardization indiscriminately, regardless of the distribution of data quality. In contrast, here we used an approach in which regional biodiversities were estimated only when sufficient data were available to do this reliably, using a coverage estimator (see Methods). New and improved data, coupled with more appropriate methods, likely explains the differences between our results and that of previous work on crocodylomorphs6, but it remains to be seen whether the difference with the dinosaurian pattern27 is genuine.

(a) Palaeolatitudinal spread of all non-marine pseudosuchian (red circles) and all non-marine tetrapod (black circles) occurrences through time. (b–d) Global palaeocontinental reconstructions from Fossilworks showing the distribution of all pseudosuchian occurrences in the (b) Cretaceous (145–66 Myr ago), (c) Eocene (56–33.9 Myr ago) and (d) Miocene (23–5.3 Myr ago).

Biodiversity across the K/Pg boundary

The Cretaceous witnessed the non-marine radiations of notosuchians8,19,26 and eusuchians, with crocodylians diversifying from within Eusuchia during the Late Cretaceous (Santonian–Maastrichtian)9,28. Despite this, subsampled non-marine biodiversity decreased from the Campanian into the Maastrichtian in both Europe and North America (Figs 2a and 3c), on the ∼9 million-year timescale resolution of our study. This decrease in biodiversity prior to the K/Pg mass extinction event (66 Myr ago) mirrors the pattern seen in North American mammals29 and some dinosaur groups30. However, rather than signalling that a protracted global catastrophe caused the K/Pg mass extinction, this latest Cretaceous decline of crocodylomorphs tracks a long-term trend towards cooler temperatures through the Late Cretaceous31,32. This is consistent with the ‘background’ coupling between biodiversity and global climate observed throughout the late Mesozoic and Cenozoic (see below), and likely characteristic of the entire evolutionary history of Pseudosuchia.

The effect of the K/Pg mass extinction on crocodylomorphs has previously been perceived as minor or non-existent19,28, with any extinction temporally staggered33. However, several non-marine groups with high biodiversity before the boundary became extinct (most notably all non-sebecid notosuchians34), and only two clades (the marine dyrosaurids and terrestrial sebecids) survived alongside crocodylians28,35. Nevertheless, the extinctions of these groups, and other non-marine crocodylomorph taxa were balanced by rapid radiations of the three surviving clades in the early Paleocene19,28,34,36, including substantial range expansions of marine dyrosaurids36,37 and terrestrial alligatoroids28 into South America. Range expansions and increases in regional taxon counts among dyrosaurids35,36,37 and gavialoid crocodylians38 led to a substantial increase in global marine crocodylomorph biodiversity by the late Paleocene (Fig. 2c), with crocodylomorphs potentially benefiting from the extinction of many other marine reptiles at the K/Pg boundary36,39.

Non-marine biodiversity and palaeotemperature

Relative changes in subsampled non-marine biodiversity in both North America and Europe track each other and the δ18O palaeotemperature proxy17,40 through the Cenozoic (Fig. 2a; Table 1). The relationship between these variables is characterised by near-zero, negative serial correlation for North American data, and high, negative serial correlation for European data. The occurrence of near-zero estimated serial correlation suggests links between high amplitude, long-term patterns, with weaker correspondence between low amplitude, short-term fluctuations. Nevertheless, a similar relationship is still recovered when serial correlation is assumed to equal zero, and for the European data when it is assumed to equal one (Table 1), demonstrating robustness of this result to statistical approach. Furthermore, the recovery of near-identical patterns of relative standing biodiversity from separate European and North American occurrence datasets suggests that our subsampling approach is effective in recovering a shared underlying biodiversity pattern.

Paleogene non-marine biodiversity

These North American and European patterns indicate that non-marine crocodylomorphs remained diverse at temperate palaeolatitudes (30–60°) during the early Paleogene greenhouse world (66–41 Myr ago). There is no evidence for transient biodiversity increases driven by the short-term Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (56 Myr ago), possibly because the timescale of species origination and phenotypic divergence that would allow speciation to be recognisable in the fossil record is longer than that of this rapid climatic event (>5 °C in <10,000 years4). Nevertheless, early Eocene crocodylomorphs expanded their palaeogeographic range to at least 75°N7 (Fig. 4a,c), coinciding with the sustained high temperatures of the Early Eocene Climatic Optimum (53–50 Myr ago)41. A major European and North American biodiversity peak during the middle Eocene (48–41 Myr ago; Fig. 2a) is composed primarily of crocodylians, with sebecids, previously known only from South America34, also present in Europe42. However, although this interval includes the short-term hyperthermal Mid-Eocene Climatic Optimum, the overall trend is one of cooling17, indicating a temporary decoupling of temperature and biodiversity. At temperate palaeolatitudes, a stark late Eocene–Oligocene (41–23 Myr ago) decline to unprecedentedly low biodiversity (Figs 2a and 3d) coincides with global cooling, the development of a strengthened latitudinal temperature gradient43, and the onset of Antarctic glaciation17. Unfortunately, southern hemisphere and palaeotropical (0–30°) sampling (Fig. 3d) is inadequate to determine additional patterns of Paleogene biodiversity, including the form of palaeolatitudinal biodiversity gradients. This also means that we cannot determine whether the correlation between palaeotemperature and non-marine biodiversity was restricted to northern temperate palaeolatitudes, or was a global pattern, during the Paleogene. If the latter is shown to have been the case, then we should ultimately expect to find extremely high Paleogene biodiversity in currently poorly sampled regions such as South America. Alternatively, temperature change might drive pseudosuchian biodiversity only at limiting, low–medium temperatures. At high, non-limiting temperatures, other factors such as aridity might become limiting, as suggested by low-latitude Cenozoic biodiversity patterns described below.

Cenozoic marine biodiversity

Marine crocodylomorph biodiversity decreased in the early Eocene (Fig. 2b), with the loss of basal gavialoids (‘thoracosaurs’) and decline in dyrosaurids, with the latter group becoming extinct in the middle–late Eocene16,28,37. This observation conflicts with the conclusions of a recent study that did not use subsampling approaches16, the authors of which proposed that marine crocodylomorphs generally diversified during warm intervals. Furthermore, contrary to the findings of those authors16, there is no statistical relationship between the δ18O palaeotemperature proxy and marine crocodylomorph biodiversity in any of our analyses, whether or not subsampling is applied (Table 2). This differs from the approach of Martin et al.16, who found correlations between their palaeotemperature proxy and marine crocodylomorph biodiversity, but only once metriorhynchoid thalattosuchians were excluded. They used this finding as evidence for an assertion that metriorhynchoids had a distinct biology from other marine crocodylomorphs. However, a more conservative reading of these results is that marine crocodylomorph biodiversity was not consistently linked to temperature over the studied interval.

Instead, our analyses find strong, significant relationships between subsampled marine genus counts and eustatic sea level estimates of Miller et al.18 when including a ‘phase’ variable (see Methods) to distinguish the amplitude of thalattosuchian biodiversity patterns from that of stratigraphically younger marine radiations (Table 2). This regression model explains more than 60% of the variance in subsampled marine biodiversity. Directly counted marine genera have a marginally significant relationship with sea level (Table 2). The negative slopes of the ‘phase’ variable in these regression models indicate that thalattosuchians attained higher biodiversities relative to sea level than did stratigraphically younger marine crocodylomorphs. Our results support previous observations that continental flooding, through eustatic sea level change, shaped the evolution of marine shelf biodiversity44,45, including that of near-shore marine reptiles22. Other extrinsic factors might also be important; for example, it is likely that post-extinction opportunism contributed to high biodiversity of early Paleogene marine crocodylomorphs, which show a substantial post-extinction biodiversity increase that was facilitated by inter-continental range expansion36,39. Marine crocodylomorph biodiversity remained low through the remainder of the Paleogene and early Neogene (Fig. 2b), comprising a small number of gavialoids46 and tomistomines28,47, before their present day restriction to non-marine environments.

Neogene non-marine biodiversity

Temperate palaeolatitudinal biodiversity remained low among Neogene non-marine crocodylomorphs, although a minor peak might be coincident with the Mid-Miocene Climatic Optimum (15 Myr ago; Fig. 2a). There is clear evidence for latitudinal range contraction through time both on the continents (Fig. 4) and in the marine realm (Supplementary Fig. 5). The most poleward crocodylomorph occurrences declined to their approximate present day limits (35° N and S) by the late Miocene (Fig. 4a,d), coincident with the onset of Arctic glaciation17. This is despite the occurrence of non-crocodylomorph-bearing fossil localities documenting higher palaeolatitude tetrapod faunas, and indicates that crocodylomorph range contraction is not a sampling artefact.

Neogene terrestrial biodiversity of crocodylians was substantially higher in the palaeotropics than in temperate regions (Fig. 2a), with sufficient data to demonstrate a palaeotropical peak from the early Miocene (Fig. 3e–g). High palaeotropical biodiversity in the middle–late Miocene is linked to the timing of the rapid radiation and dispersal of Crocodylus48 and other crocodyloid lineages49, and the presence of highly diverse sympatric assemblages of crocodylians in the proto-Amazonian mega-wetlands of South America50,51. Nevertheless, palaeotropical crocodylomorph biodiversity declined in the late Miocene of Africa (Figs 2a and 3e), coincident with the formation of the Sahara Desert52 and sub-Saharan expansion of savannah environments53. A similar decline ensued in the post-Miocene palaeotropics of South America (Figs 2a and 3e), and has been attributed to hydrographic changes and the disappearance of the mega-wetlands52,53, driven by Andean uplift54. The overall dwindling of crocodylomorph biodiversity towards the present day tracks the late Cenozoic cooling trend17, increasing aridification52 and the rising predominance of grassland ecosystems during the late Neogene53, the Quaternary Ice Ages17 and presumably the more recent impact of human activity.

The future of crocodylians

Our findings show that the biodiversity of non-marine pseudosuchians has been strongly linked to both spatial and temporal temperature variation, as well as the spatial distribution of aridity, throughout the group’s evolutionary history. This can be demonstrated most clearly during the Cenozoic, where the long-term decline of crocodylomorphs at temperate latitudes over the last 50 million years has been driven by the descent into the modern-day icehouse world, and the geographic pattern of decline among palaeotropical taxa in the Neogene matches patterns of aridification in Africa and South America. As the Earth continues to warm, perhaps heading towards a greenhouse world comparable to that of the early Paleogene4, we might therefore expect that higher temperatures should promote long-term increases in crocodylian biodiversity and the expansion of the group’s latitudinal range outside of the tropics, as was the case for much of their Mesozoic and early Cenozoic history. However, in contrast to these earlier times, predictions of the distribution of their future biodiversity are complicated by the impact of human activity on habitat loss and fragmentation, which are likely to reduce the rate and magnitude of crocodylian range expansion1, especially into populated regions.

Methods

Pseudosuchian occurrences data set

Following extensive work to ensure that occurrences and taxonomic opinions were consistent and up-to-date with the literature55, the Paleobiology Database (PaleoDB; http://paleobiodb.org) includes a near-comprehensive dataset of all published pseudosuchian occurrences spanning the Middle Triassic through to the Pleistocene, a period of nearly 250 million years. Pseudosuchian body fossil occurrences that could be assigned to genera (including qualifiers such as cf. and aff.) were downloaded from this database (comprising 2,767 fossil occurrences representing 386 genera), accessed via Fossilworks (http://fossilworks.org), on 23 February 2015.

Genera were used so as to incorporate specifically indeterminate material, enabling us to include more data points in our analyses, and also to avoid problems with using species as a unit for estimating palaeobiodiversity56. This is especially pertinent to analyses of the pseudosuchian fossil record, where certain parts of the tree have been the focus of intensive taxonomic work at the species level (for example, Thalattosuchia57), whereas other clades are composed primarily of monospecific genera (for example, Notosuchia26), and some groups have received relatively little attention (for example, Tomistominae47). Despite this issue, fluctuations in the numbers of genera and species are near-identical in both the marine and non-marine realms (Supplementary Fig. 1). The sole exception to this pattern is that there is a continued increase in non-marine species numbers in our most recent time bin (Supplementary Fig. 1), in contrast to the decline that occurs in genera (Fig. 1; Supplementary Fig. 1). We also plotted ratios of non-marine species to genera through time, which shows no significant trend (Supplementary Fig. 2). However, the Neogene differs from earlier periods in pseudosuchian history in having high species to genus ratios (Supplementary Fig. 2). We suggest that these deviations in the Neogene reflect the relative ease of recognizing modern species in the recent fossil record, with most living species belonging to just a small number of genera, and is therefore best considered a ‘Pull of the Recent’ type effect.

Extant genera, especially Alligator and Crocodylus, have been used as ‘wastebasket taxa’ for indeterminate or non-referable fossil species. Therefore, we modified occurrences of Crocodylus and Alligator before analysis, as explained in the Supplementary Methods. We also reviewed Cretaceous thalattosuchian occurrences, to help constrain marine crocodylomorph biodiversity over the J/K boundary (Supplementary Methods).

The resultant pseudosuchian data set was subdivided into non-marine (terrestrial plus freshwater; Supplementary Data 1) and marine taxa (Supplementary Data 2) using an amended version of a list of the names of Mesozoic–Ypresian tetrapod taxa presented in Benson et al. (in review). Environmental assignment (marine versus non-marine) for post-Ypresian taxa was based primarily on facies data recorded in the PaleoDB and information presented in refs 16, 28, 46. Vélez-Juarbe et al.46 demonstrated the marine affinities of several late Oligocene–Neogene gavialoids, including Aktiogavialis, Piscogavialis and Siquisiquesuchus; these were omitted from the marine crocodylomorph data set of Martin et al.16 without comment, but are incorporated as marine taxa here. Although some stratigraphically older species currently included within Tomistoma were probably marine47, most occurrences (including the extant species T. schlegelii) are non-marine, or their environments are unknown; as such, here we treat Tomistoma as non-marine.

Subsampling protocol

Pseudosuchian genera were assigned to approximately equal-length (9 million years) stratigraphic time bins (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Data 3). Although there is variation in time bin duration, there is no significant trend of interval duration through time (Supplementary Fig. 3). We applied equal coverage or ‘shareholder quorum’ subsampling (SQS)58 to ameliorate the effects of uneven sampling and to reconstruct temporal patterns in past biodiversity. SQS tracks the ‘coverage’ of each subsampling pool represented by the taxa that have been drawn58. Coverage is the sum of the proportional frequencies of the taxa sampled in each time bin, and coverage of observed data is modified to estimate the coverage of the real taxon distribution for each sample pool. This is achieved by multiplying coverage of the observed data by Good’s u: the proportion of occurrences representing non-singleton taxa58,59. Each interval can therefore only be subsampled to a maximum quorum level (i.e. amount of coverage) equal to Good’s u for that interval, meaning fewer time intervals/geographical regions can be subsampled at higher quorum levels. We used a quorum level of 0.4 for reported analyses, a level which recovers similar patterns to those at higher quorum levels based on marine invertebrate data sets58,59, and unreported analyses of our pseudosuchian data. The substantial advantage of SQS over other subsampling methods, such as classical rarefaction, is that it is robust to the tendency of those methods to ‘flatten out’ biodiversity curves58. It has been suggested that SQS can remove genuine biodiversity signals when they are driven by environmental variables that jointly drive geological sample availability45. This does not seem to be the case in our data, as the correlations of environmental variables with subsampled biodiversity estimates are stronger than those with face value biodiversity counts (Tables 1 and 2). Furthermore, independent data on pseudosuchian biodiversity in the northern temperate regions, from North America and from Europe, yield highly congruent subsampled biodiversity curves. This is consistent with the effective estimation of a shared underlying biodiversity pattern, although we acknowledge that the adequacy of the SQS method would benefit from more detailed investigation, building on simulation studies60.

In determining Good’s u, singleton taxa were defined based on occurrences within collections61, rather than publications58,59. Entire fossil collections, containing lists of species occurrences, were drawn62. Because poorly studied spatiotemporal regions could appear well sampled for stochastic reasons, returning spuriously low subsampled biodiversity estimates, time bins with fewer than six publications were excluded from our analyses. Whenever a collection corresponding to a new publication was drawn, subsequent collections were drawn from that publication only until all or three collections from that publication had been sampled61. Results are based on 1,000 subsampling trials. The PERL script used for implementing SQS is provided in Supplementary Data 4, and was written and provided by J. Alroy.

Patterns in non-marine and marine taxa were analysed separately, to avoid problems with sampling from heterogeneous environments58,59. Marine pseudosuchian genera, which have wide geographic distributions, were analysed as a global data set. However, high levels of endemism are evident in non-marine genera, which were therefore analysed across a set of continental regions (Africa, Asia, Australasia, Europe, North America and South America) representing regional biotas of approximately equal geographic spread. For each continental region, we selected countries that were well-sampled and cohesive through geological time, and therefore valid for deep time analyses. We also attempted to make the geographic spread of data relatively even among continents by excluding far-outlying countries (Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Table 2).

In addition to producing sub-sampled terrestrial and marine biodiversity curves through time, we also analysed the palaeolatitudinal distribution of terrestrial biodiversity. This was implemented through plots of subsampled regional biodiversity against the regional palaeolatitudinal centroid, as well as plots of subsampling curves within time bins (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4). Plots of the palaeolatitudinal spread of all pseudosuchian and all tetrapod occurrences through time were also produced for non-marine (Fig. 4a) and marine taxa (Supplementary Fig. 5). Collections in the Paleobiology Database are assigned present-day coordinates and geological ages. These two pieces of information are combined with palaeogeographic rotation models provided by C. Scotese (http://www.scotese.com) to obtain reconstructed palaeogeographic positions for each occurrence.

Correlation of biodiversity with palaeotemperature and sea level

We compared subsampled genus biodiversities at a quorum of 0.4 to δ18O palaeotemperature proxies and sequence stratigraphic eustatic sea level estimates in two sets of analyses: (1) terrestrial pseudosuchian biodiversity in North America and Europe were each compared to the Zachos et al.17 compendium of benthic foraminifera isotopic values (Supplementary Data 5), which spans the latest Maastrichtian to Cenozoic; and (2) global marine pseudosuchian genus biodiversity was compared to the eustatic sea level estimates of Miller et al.18 (Supplementary Data 6) and δ18O from the Prokoph et al.40 compendium (Supplementary Data 7), which includes Jurassic–Recent temperate palaeolatitudinal sea surface isotopic values from a range of marine organisms, adjusted for vital effects.

Although a contentious issue in crocodylomorph phylogeny, we follow the most recent placement of Thalattosuchia as a basal clade outside of Crocodyliformes63, rather than within Neosuchia (for example, ref. 26). Consequently, we consider crocodylomorphs to have independently become adapted to marine life in the Jurassic (Thalattosuchia) and Cretaceous (pholidosaurids, dyrosaurids and eusuchians), representing separate temporal and evolutionary replicates that are characterised by distinct groups with possible different biodiversity dynamics. We therefore also analysed relationships between marine biodiversity and climatic variables including a binary variable denoting ‘1’ for Jurassic–Hauterivian (mid-Early Cretaceous) intervals and ‘2’ for stratigraphically younger intervals. Supplementary Figure 6 shows the palaeotemperature and sea level curves with the weighted means used in our time series regressions. Supplementary Fig. 7 shows plots of subsampled marine biodiversity versus δ18O and sea level, with and without the application of first differencing.

The similarity of these independent isotopic databases17,40 for the overlapping portion of geological time suggests that both capture broad patterns of global climate change. Martin et al.16 compared Jurassic–late Eocene marine crocodylomorph biodiversity with a sea surface temperature (SST) curve established from δ18O values of fish teeth from the Western Tethys. One potential problem with this method is that the fish teeth are from a variety of different species and genera, with Lécuyer et al.64 noting that species-specific differences in fractionation of δ18O can occur. In addition, there might be differences between the isotopic fractionation that occurs between phosphate and water, and that which takes place in the fish teeth64. Despite these potential issues, their SST curve broadly follows the δ18O curves of Prokoph et al.40 and Zachos et al.17, suggesting that the overall pattern between them is congruent. However, the benthic δ18O dataset for deep sea palaeotemperatures of Zachos et al.17 is much better resolved than that of the SST curve, and the Prokoph et al.40 data set spans a larger time interval. Consequently, we consider these two datasets17,40 better suited to testing for a correlation between palaeotemperature and biodiversity than the SST curve16,64. Time-weighted mean values of each of these two data sets were calculated and used in the regression analyses below.

Statistical comparison was made using time series approaches, specifically generalised least squares (GLS) regression incorporating a first-order autoregressive model (for example, refs 22, 65, 66), and implemented in the R package nlme, using the gls() function67. This estimates the strength of serial correlation in the relationship between variables using maximum likelihood during the regression model-fitting process, correcting for the non-independence of adjacent points within a time series. We compared the results to those of ordinary least squares regression using untransformed data, which assumes serial correlation=0. Because intervals lacking marine pseudosuchians, and intervals that did not meet our quorum level due to data deficiency were excluded, our regression analyses ask whether pseudosuchian diversity was correlated to environmental variables when pseudosuchians were present at all.

All analyses were performed in R version 3.0.2 (ref. 68) and using a customized PERL script provided by J. Alroy. Additional information is provided in the Supplementary Methods.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Mannion, P. D. et al. Climate constrains the evolutionary history and biodiversity of crocodylians. Nat. Commun. 6:8438 doi: 10.1038/ncomms9438 (2015).

References

IPCC 2014: Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. in Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Core Writing Team R.K., Pachauri, Meyer L.A.) 151 IPCC (2014).

Markwick, P. J. Fossil crocodilians as indicators of Late Cretaceous and Cenozoic climates: implications for using palaeontological data in reconstructing palaeoclimate. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 137, 205–271 (1998).

Mayhew, P. J., Bell, M. A., Benton, T. G. & McGowan, A. J. Biodiversity tracks temperature over time. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 15141–15145 (2012).

McInerney, F. A. & Wing, S. L. The Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum: a perturbation of carbon cycle, climate, and biosphere with implications for the future. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet Sci. 39, 489–516 (2011).

Butler, R. J. et al. The sail-backed reptile Ctenosauriscus from the latest Early Triassic of Germany and the timing and biogeography of the early archosaur radiation. PLoS ONE 6, e25693 (2011).

Markwick, P. J. Crocodilian diversity in space and time: the role of climate in paleoecology and its implication for understanding K/T extinctions. Paleobiology 24, 470–497 (1998b).

Jetz, W., Thomas, G. H., Joy, J. B., Hartmann, K. & Mooers, A. O. The global diversity of birds in space and time. Nature 491, 444–448 (2012).

Carvalho, I. S., Gasparini, Z. B., Salgado, L., de Vasconcellos, F. M. & Marinho, T. S. Climate’s role in the distribution of the Cretaceous terrestrial Crocodyliformes throughout Gondwana. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 297, 252–262 (2010).

Martin, J. E. & Delfino, M. Recent advances in the comprehension of the biogeography of Cretaceous European eusuchians. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 293, 406–418 (2010).

Buffetaut, E. Radiation évolutive, paléoécologie et biogéographie des crocodiliens mésosuchiens. Mém. Soc. Géol. Fr. 42, 1–88 (1982).

Brochu, C. A. Crocodilian snouts in space and time: phylogenetic approaches toward adaptive radiation. Am. Zool. 41, 564–585 (2001).

Pierce, S. E., Angielczyk, K. D. & Rayfield, E. J. Morphospace occupation in thalattosuchian crocodylomorphs: skull shape variation, species delineation and temporal patterns. Palaeontology 52, 1057–1097 (2009).

Stubbs, T. L., Pierce, S. E., Rayfield, E. J. & Anderson, P. S. L. Morphological and biomechanical disparity of crocodile-line archosaurs following the end-Triassic extinction. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B 280, 20131940 (2013).

Sereno, P. C. & Larsson, H. C. E. Cretaceous Crocodyliforms from the Sahara. ZooKeys 28, 1–143 (2009).

Sereno, P. C., Larsson, H. C. E., Sidor, C. A. & Gado, B. The giant crocodyliform Sarcosuchus from the Cretaceous of Africa. Science 294, 1516–1519 (2001).

Martin, J. E., Amiot, R., Lécuyer, C. & Benton, M. J. Sea surface temperature contributes to marine crocodylomorph evolution. Nat. Commun 5, 4658 (2014).

Zachos, J. C., Dickens, G. R. & Zeebe, R. E. An early Cenozoic perspective on greenhouse warming and carbon-cycle dynamics. Nature 451, 279–283 (2008).

Miller, K. G. et al. The Phanerozoic record of global sea level change. Science 310, 1293–1297 (2005).

Bronzati, M., Montefeltro, F. C. & Langer, M. C. Diversification events and the effects of mass extinctions on Crocodyliformes evolutionary history. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2, 140385 (2015).

Willig, M. R., Kaufman, D. M. & Stevens, R. D. Latitudinal gradients of biodiversity: pattern, process, scale, and synthesis. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 34, 273–309 (2003).

Toljagic, O. & Butler, R. J. Triassic–Jurassic mass extinction as trigger for the Mesozoic radiation of crocodylomorphs. Biol. Lett. 9, 20130095 (2013).

Benson, R. B. J. & Butler, R. J. Uncovering the diversification history of marine tetrapods: ecology influences the effect of geological sampling bias. Geol. Soc. London Spec. Publ. 358, 191–207 (2011).

Benson, R. B. J. et al. Cretaceous tetrapod fossil record sampling and faunal turnover: implications for biogeography and the rise of modern clades. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 372, 88–107 (2013).

Benson, R. J. B., Butler, R. J., Lindgren, J. & Smith, A. S. Mesozoic marine tetrapod diversity: mass extinctions and temporal heterogeneity in geological megabiases affecting vertebrates. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B 277, 829–834 (2010).

Young, M. T., Andrade, M. B., Cornée, J.-J., Steel, L. & Foffa, D. Re-description of a putative Early Cretaceous "teleosaurid" from France, with implications for the survival of metriorhynchids and teleosaurids across the Jurassic-Cretaceous Boundary. Ann. Paléontol. 100, 165–174 (2014).

Pol, D. et al. A new notosuchian from the Late Cretaceous of Brazil and the phylogeny of advanced notosuchians. PLoS ONE 9, e93105 (2014).

Mannion, P. D. et al. A temperate palaeodiversity peak in Mesozoic dinosaurs and evidence for Late Cretaceous geographical partitioning. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 21, 898–908 (2012).

Brochu, C. A. Phylogenetic approaches toward crocodylian history. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet Sci. 31, 357–397 (2003).

Newham, E., Benson, R. B. J., Upchurch, P. & Goswami, A. Mesozoic mammaliaform diversity: The effect of sampling corrections on reconstructions of evolutionary dynamics. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 412, 32–44 (2014).

Brusatte, S. L. et al. The extinction of the dinosaurs. Biol. Rev. 90, 628–642 (2015).

Hong, S. K. & Lee, Y. I. Evaluation of atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations during the Cretaceous. Earth Planet Sci. Lett 327–328, 23–28 (2012).

Linnert, C. et al. Evidence for global cooling in the Late Cretaceous. Nat. Commun. 5, 4194 (2014).

Russell, A. P. & Wu, X.-C. The Crocodylomorpha at and between geological boundaries: the Baden-Powell approach to change? Zoology 100, 164–182 (1997).

Kellner, A. W. A., Pinheiro, A. E. P. & Campos, D. A. A new sebecid from the Paleogene of Brazil and the crocodyliform radiation after the K–Pg boundary. PLoS ONE 9, e81386 (2014).

Hill, R. V. et al. Dyrosaurid (Crocodyliformes: Mesoeucrocodylia) fossils from the Upper Cretaceous and Paleogene of Mali: Implications for Phylogeny and Survivorship across the K/T Boundary. Am. Mus. Novit. 3631, 1–19 (2008).

Barbosa, J. A., Kellner, A. W. A. & Viana, M. S. S. New dyrosaurid crocodylomorph and evidences for faunal turnover at the K–P transition in Brazil. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B 275, 1385–1391 (2008).

Hastings, A. K., Bloch, J. I., Cadena, E. & Jaramillo, C. A. A new small short-snouted dyrosaurid (Crocodylomorpha, Mesoeucrocodylia) from the Paleocene of Northeastern Colombia. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 30, 139–162 (2010).

Brochu, C. A. Osteology and phylogenetic significance of Eosuchus minor (Marsh, 1870) new combination, a longirostrine crocodylian from the late Paleocene of North America. J. Paleontol. 80, 162–186 (2006).

Jouve, S., Bouya, B. & Amaghzaz, M. A long-snouted dyrosaurid (Crocodyliformes, Mesoeucrocodylia) from the Paleocene of Morocco: phylogenetic and paleobiogeographic implications. Palaeontology 51, 281–294 (2008).

Prokoph, A., Shields, G. A. & Veizer, J. Compilation and time-series analysis of a marine carbonate δ18O, δ13C, 87Sr/86Sr and δ34S database through Earth history. Earth Sci. Rev. 87, 113–133 (2008).

Pearson, P. N. et al. Stable warm tropical climate through the Eocene Epoch. Geology 35, 211–214 (2007).

Martin, J. E. A sebecosuchian in a middle Eocene karst with comments on the dorsal shield in Crocodylomorpha. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 60, 673–680 (2015).

Bijl, P. K. et al. Early Palaeogene temperature evolution of the southwest Pacific Ocean. Nature 461, 776–779 (2009).

Peters, S. E. Geologic constraints on the macroevolutionary history of marine animals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 12326–12331 (2005).

Hannisdal, B. & Peters, S.E. Phanerozoic Earth system evolution and marine biodiversity. Science 334, 1121–1124 (2011).

Vélez-Juarbe, J., Brochu, C. A. & Santos, H. A gharial from the Oligocene of Puerto Rico: transoceanic dispersal in the history of a non-marine reptile. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B 274, 1245–1254 (2007).

Piras, P., Delfino, M., Favero, L. & Kotsakis, T. Phylogenetic position of the crocodylian Megadontosuchus arduini and tomistomine palaeobiogeography. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 52, 315–328 (2007).

Oaks, J. R. A time-calibrated species tree of Crocodylia reveals a recent radiation of true crocodiles. Evolution 65, 3285–3297 (2011).

Brochu, C. A., Njau, J., Blumenschine, R. J. & Densmore, L. D. A new horned crocodile from the Plio-Pleistocene hominid sites at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. PLoS ONE 5, e9333 (2010).

Scheyer, T. M. et al. Crocodylian diversity peak and extinction in the late Cenozoic of the northern Neotropics. Nat. Commun. 4, 1907 (2013).

Salas-Gismondi, R. et al. A Miocene hyperdiverse crocodylian community reveals peculiar trophic dynamics in proto-Amazonian mega-wetlands. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B 282, 20142490 (2015).

Zhang, Z. et al. Aridification of the Sahara Desert caused by Tethys Sea shrinkage during the Late Miocene. Nature 513, 401–404 (2014).

Strömberg, C. A. E. Evolution of grasses and grassland ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet Sci. 39, 517–544 (2011).

Hoorn, C. et al. Amazonia through time: andean uplift, climate change, landscape evolution, and biodiversity. Science 330, 927–931 (2010).

Carrano, M. T., Alroy, J., Mannion, P. D., Butler, R. J. & Behrensmeyer, A. K. Taxonomic occurrences of Pseudosuchia recorded in, Fossilworks, the Evolution of Terrestrial Ecosystems database, and the Paleobiology Database. Fossilworks (2015).

Smith, A. B. Large-scale heterogeneity of the fossil record: implications for Phanerozoic biodiversity studies. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London Ser. B 356, 351–367 (2001).

Young, M. T. et al. Revision of the Late Jurassic teleosaurid genus Machimosaurus (Crocodylomorpha, Thalattosuchia). R. Soc. Open Sci. 1, 140222 (2014).

Alroy, J. The shifting balance of diversity among major marine animal groups. Science 329, 1191–1194 (2010).

Alroy, J. Geographical, environmental and intrinsic biotic controls on Phanerozoic marine diversification. Palaeontology 53, 1121–1235 (2010).

Hannidsal, B., Hendericks, J. & Liow, L. H. Long-term evolutionary and ecological responses of calcifying phytoplankton to changes in atmospheric CO2 . Global Change Biol. 18, 3504–3516 (2012).

Alroy, J. Accurate and precise estimates of origination and extinction rates. Paleobiology 40, 374–397 (2014).

Alroy, J. et al. Effects of sampling standardization on estimates of Phanerozoic marine diversification. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 6261–6266 (2001).

Wilberg, E. W. What’s in an Outgroup? The Impact of outgroup choice on the phylogenetic position of Thalattosuchia (Crocodylomorpha) and the origin of Crocodyliformes. Syst. Biol. 64, 621–637 (2015).

Lécuyer, C., Amiot, R., Touzeau, A. & Trotter, J. Calibration of the phosphate δ18O thermometer with carbonate–water oxygen isotope fractionation equations. Chem. Geol. 347, 217–226 (2013).

Hunt, G., Cronin, T. M. & Roy, K. Species-energy relationship in the deep sea: a test using the Quaternary fossil record. Ecol. Lett. 8, 739–747 (2005).

Marx, F. G. & Uhen, M. D. Climate, critters, and cetaceans: Cenozoic drivers of the evolution of modern whales. Science 327, 993–996 (2010).

Pinheiro, J., Bates, D., DebRoy, S. & Sarkar, D. The R Development Core Team. nlme: Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R package version 3, 1–113 (2013).

R Core Team. R: Language And Environment For Statistical Computing R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2013).

Chatfield, C. The Analysis of Time Series: An Introduction, Sixth Edition Chapman and Hall/CRC (2003).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the efforts of all those who have collected pseudosuchian data, and to all those who have also entered this data into the Paleobiology Database, especially J. Alroy, A. Behrensmeyer and M. Uhen. J. Alroy provided the PERL script used to perform subsampling analyses. K. Littler offered valuable insights on climatic data, and S. Peters provided constructive comments on methodological approach. P.D.M.’s research was supported by an Imperial College London Junior Research Fellowship and a Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellowship (ECF-2014-662). R.J.B. received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme 2014–2018 under grant agreement 637483 (ERC Starting Grant: TERRA), as well as from a Marie Curie Career Integration Grant (PCIG14-GA-2013-630123). J.P.T. is funded by a NERC PhD studentship (EATAS G013 13). Part of the Cretaceous dataset was compiled by R.B.J.B. via Leverhulme Foundation Grant RPG-129, awarded to P. Upchurch. This is Paleobiology Database official publication number 235.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.D.M., R.B.J.B. and R.J.B. conceived and designed the research. P.D.M., R.B.J.B., R.J.B., J.P.T. and M.T.C. compiled the data. R.B.J.B. carried out the analyses. P.D.M. and R.B.J.B. prepared the figures. All authors discussed the results and contributed to writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-7, Supplementary Tables 1-2, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References (PDF 1053 kb)

Supplementary Data 1

Non-marine pseudosuchian data (TXT 1058 kb)

Supplementary Data 2

Marine pseudosuchian data (TXT 208 kb)

Supplementary Data 3

Time intervals table (TXT 1 kb)

Supplementary Data 4

PERL script for SQS (provided by John Alroy) (TXT 44 kb)

Supplementary Data 5

Zachos et al. (2008) palaeotemperature proxy isotope data (TXT 531 kb)

Supplementary Data 6

Miller et al. (2005) sea level data (TXT 82 kb)

Supplementary Data 7

Prokoph et al. (2008) palaeotemperature proxy isotope data (TXT 44 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Mannion, P., Benson, R., Carrano, M. et al. Climate constrains the evolutionary history and biodiversity of crocodylians. Nat Commun 6, 8438 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms9438

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms9438

This article is cited by

-

Decoupling speciation and extinction reveals both abiotic and biotic drivers shaped 250 million years of diversity in crocodile-line archosaurs

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2023)

-

Global diversity dynamics in the fossil record are regionally heterogeneous

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Reconstructed evolutionary patterns for crocodile-line archosaurs demonstrate impact of failure to log-transform body size data

Communications Biology (2022)

-

Functional and ecomorphological evolution of orbit shape in mesozoic archosaurs is driven by body size and diet

Communications Biology (2022)

-

Reinterpretation of girdled lizard remains from Switzerland documents the first occurrence of the lacertid Janosikia outside of Germany

PalZ (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.