Abstract

The physical mechanisms responsible for the formation of a two-dimensional electron gas at the interface between insulating SrTiO3 and LaAlO3 have remained a contentious subject since its discovery in 2004. Opinion is divided between an intrinsic mechanism involving the build-up of an internal electric potential due to the polar discontinuity at the interface between SrTiO3 and LaAlO3, and extrinsic mechanisms attributed to structural imperfections. Here we show that interface conductivity is also exhibited when the LaAlO3 layer is diluted with SrTiO3, and that the threshold thickness required to show conductivity scales inversely with the fraction of LaAlO3 in this solid solution, and thereby also with the layer's formal polarization. These results can be best described in terms of the intrinsic polar-catastrophe model, hence providing the most compelling evidence, to date, in favour of this mechanism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Remarkable and unexpected phenomena have been discovered at oxide heterostructure interfaces1,2,3,4,5, which have a fundamental and potentially technological impact on future oxide-based devices. A paradigm example is the observed two-dimensional conductivity at the LaAlO3/SrTiO3 (LAO/STO) interface, originally explained in terms of the so-called polar-catastrophe scenario2,6,7. In this model, an intrinsic electronic reconstruction at the interface is expected from the build-up of an internal electrical potential in LAO as the film thickness t increases, owing to the polar discontinuity at the interface between LAO, which consists of alternating positively and negatively charged layers, (LaO)+ and (AlO2)−, and STO, with charge-neutral layers.

The main success of the polar-catastrophe scenario is that it very accurately predicts the critical thickness tc originally observed experimentally by Thiel et al.7,8, a very robust result that has been replicated in several laboratories9,10 and also predicted from first-principles calculations on ideal STO/LAO/vacuum stacks11,12. However, the surface of LAO and its interface with STO are far from ideal, therefore alternative and extrinsic effects have been invoked to explain the observed conductivity, such as oxygen vacancies13,14,15, adsorbates at the LAO surface16,17, or interfacial intermixing18,19,20. Also, the presence of an internal electric field within LAO, a key feature of the intrinsic scenario, was seriously questioned from X-ray photoemission measurements21. Nonetheless, more recent surface X-ray diffraction measurements revealed both an atomic rumpling in the LAO layer22, a clear signature of an internal electric field, and an expansion of the LAO c-axis unit-cell parameter, fully compatible with an electrostrictive effect produced by the same field23.

From the above, it is clear that further compelling evidence in favour of one mechanism or the other is urgently required to obtain a unifying consensus about this fascinating system8. Here we describe experiments performed to further assess the relative importance of the intrinsic polar-catastrophe scenario and the extrinsic intermixing model to explain the origin of the conductivity. To achieve this, we replaced pure LAO with ultrathin films of LAO diluted with STO ((LaAlO3) x(SrTiO3)1−x, or LASTO:x) for different values of x. This system is both intermixed and has a formal polarization different to that of pure LAO. In this manner, we could observe whether tc properly evolves with the formal polarization and dielectric constant of this material, as predicted by the polar-catastrophe model, while also investigating the possible role of the extrinsic mechanism of intermixing. In conjunction with ab-initio calculations, it emerges that the obtained results can be best understood in terms of the originally proposed mechanism of the polar catastrophe.

Results

First-principles calculations

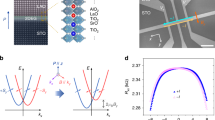

The intrinsic doping mechanism, illustrated in Fig. 1, was elegantly reformulated in the framework of the modern theory of polarization24: LAO has a formal polarization  C m−2 (where S is the unit-cell cross-section in the plane of the interface), whereas in nonpolar STO,

C m−2 (where S is the unit-cell cross-section in the plane of the interface), whereas in nonpolar STO,  . The preservation of the normal component of the electric displacement field D along the STO/LAO/vacuum stack in the absence of free charge at the surface and interface (D=0) requires the appearance of a macroscopic electric field ELAO. Because of the dielectric response of LAO, this field is

. The preservation of the normal component of the electric displacement field D along the STO/LAO/vacuum stack in the absence of free charge at the surface and interface (D=0) requires the appearance of a macroscopic electric field ELAO. Because of the dielectric response of LAO, this field is  , where

, where  is the relative permittivity of LAO25.

is the relative permittivity of LAO25.

(a) The band-level scheme shows band bending in the pure LAO layer of the valence band (VB) and conduction band (CB), and the critical thickness tc and potential build-up eVc required to induce the electronic reconstruction.  is the valence-band offset between STO and LAO. (b) LAO schematic atomic structure and (c) LAO planar charge distribution. (d) Schematic of the potential build-up as a function of its thickness t for LAO and LASTO:0.5, assuming the same relative permittivity but different formal polarizations P0 induced by the charge of the successive A-site and B-site sublayers. The critical thicknesses for the electronic reconstruction are labelled t(1)c and t(2)c for LAO and LASTO:0.5, respectively. (e) LASTO:0.5 planar charge distribution and (f) schematic atomic structure. For (b) and (f), the atom legend is shown at the bottom.

is the valence-band offset between STO and LAO. (b) LAO schematic atomic structure and (c) LAO planar charge distribution. (d) Schematic of the potential build-up as a function of its thickness t for LAO and LASTO:0.5, assuming the same relative permittivity but different formal polarizations P0 induced by the charge of the successive A-site and B-site sublayers. The critical thicknesses for the electronic reconstruction are labelled t(1)c and t(2)c for LAO and LASTO:0.5, respectively. (e) LASTO:0.5 planar charge distribution and (f) schematic atomic structure. For (b) and (f), the atom legend is shown at the bottom.

The electric field in LAO will bend the electronic bands, as illustrated in Fig. 1a. At a thickness tc, the valence O 2p bands of LAO at the surface reach the level of the STO Ti 3d conduction bands at the interface and a Zener breakdown occurs. Above this thickness, electrons will be transferred progressively from the surface to the interface, which hence becomes metallic (Fig. 1b–d). This simple electrostatic model not only explains the conduction, but also links the formal polarization of LAO, its dielectric constant, and tc such that

where ΔE≈3.3 eV is the difference of energy between the valence band of LAO and the conduction band of STO, and e is the electron charge. This yields an estimate of tc≈3.5 monolayers (ML), in perfect agreement with experiment7.

Varying the composition of the LASTO:x films (that is, x) allows one to tune continuously the formal polarization such that  . For instance, for x=0.5, the random solid solution has alternating planes with +0.5 and −0.5 formal charges (Fig. 1e,f), compared with +1 and −1 charges in pure LAO. One must, however, also consider possible changes of the other fundamental quantities determining the critical thickness expressed in equation (1). The energy gap ΔE formally depends on the electronic bandgap of STO and the valence-band offset

. For instance, for x=0.5, the random solid solution has alternating planes with +0.5 and −0.5 formal charges (Fig. 1e,f), compared with +1 and −1 charges in pure LAO. One must, however, also consider possible changes of the other fundamental quantities determining the critical thickness expressed in equation (1). The energy gap ΔE formally depends on the electronic bandgap of STO and the valence-band offset  (Fig. 1) between the two materials, which can evolve with x. In practice, however, the O 2p valence bands of STO and LAO (x=1) are virtually aligned (φn=0.1 eV (ref. 11)) and

(Fig. 1) between the two materials, which can evolve with x. In practice, however, the O 2p valence bands of STO and LAO (x=1) are virtually aligned (φn=0.1 eV (ref. 11)) and  further diminishes with x, so that we can confidently approximate

further diminishes with x, so that we can confidently approximate  , irrespective of the composition. The dielectric constants of STO and LAO, however, differ significantly (

, irrespective of the composition. The dielectric constants of STO and LAO, however, differ significantly ( ,

,  at room temperature) and it is not obvious a priori how the dielectric constant of the solid solution will evolve with composition. To clarify this point, we performed first-principles calculations on bulk compounds of different compositions using a supercell technique (see Methods). Although the dielectric constant of the LASTO:x evolves slightly with the atomic arrangement, we observe that it remains essentially constant for x=1, 0.75 and 0.5. This result may initially seem surprising; however, the large dielectric constant of pure STO is mainly produced by a low-frequency and highly polar phonon mode related to its incipient ferroelectric character. This mode, absent in LAO, is very sensitive to atomic disorder and is stabilized at much larger frequencies through mixing with other modes for x>0.5 without contributing significantly to the dielectric constant. Hence, from the discussion above, it seems that varying the composition of the LASTO:x films (0.5≤ x<1) allows one to tune the formal polarization while keeping the other quantities in equation (1) essentially constant, that is,

at room temperature) and it is not obvious a priori how the dielectric constant of the solid solution will evolve with composition. To clarify this point, we performed first-principles calculations on bulk compounds of different compositions using a supercell technique (see Methods). Although the dielectric constant of the LASTO:x evolves slightly with the atomic arrangement, we observe that it remains essentially constant for x=1, 0.75 and 0.5. This result may initially seem surprising; however, the large dielectric constant of pure STO is mainly produced by a low-frequency and highly polar phonon mode related to its incipient ferroelectric character. This mode, absent in LAO, is very sensitive to atomic disorder and is stabilized at much larger frequencies through mixing with other modes for x>0.5 without contributing significantly to the dielectric constant. Hence, from the discussion above, it seems that varying the composition of the LASTO:x films (0.5≤ x<1) allows one to tune the formal polarization while keeping the other quantities in equation (1) essentially constant, that is,

On the basis of this argument, we therefore predict that tc=7 ML and 5 ML for x=0.5 and 0.75, respectively, a result confirmed for x=0.50 from first-principles calculations (see Methods).

Structural and electrical properties of the LASTO:x films

The crystallographic quality of the films is shown in Fig. 2a. Growth was layer-by-layer, as also seen from clear RHEED oscillations and the atomic flatness observed in atomic-force micrographs. All films were perfectly strained. The out-of-plane lattice constant of the LASTO:0.5 films was determined to be 3.83±0.01 Å, in agreement with ab-initio calculations for strained growth on STO (the pseudocubic lattice parameter of the bulk pulsed laser-deposition (PLD) target was 3.85±0.01 Å). No evidence could be found either in plane or out of plane from superstructure peaks that there was any spontaneous ordering of the cations, at least for superstructures with a periodicity an even multiple of that of the normal unit cell.

(a) X-ray diffraction patterns recorded as a function of reciprocal lattice units (r.l.u.) around the (002) peaks of the STO substrate (sharp feature) and the LASTO:0.5 films, for different film thicknesses. (b) Sheet carrier density as a function of temperature and film thickness for pure LAO and LASTO:0.5.

Neither of the mixed-composition film stoichiometries investigated produce layers that increase in conductance with thickness, as one might otherwise expect for intermixed materials that were intrinsically electrically conducting. In addition, none of the films are conducting at the top surface, but instead require careful bonding at the interface to exhibit conductivity. These metallic interfaces were characterized for their transport properties using the van der Pauw method. All samples remained metallic down to the lowest measured temperature of 1.5 K. The sheet carrier densities ns are in the range 3 to 15×1013 cm−2, although with no obvious dependence on composition or thickness of the layers (Fig. 2b). According to the polar-catastrophe model, we should expect LASTO:x samples to exhibit a lower carrier density, as the screening charge scales as x·e/2S, whereby S is the unit-cell surface area. However, as already observed for LAO/STO interfaces, the estimation of the carrier density from the Hall effect yields values up to one order of magnitude smaller than those predicted from theory, possibly suggesting a large amount of trapped interface charges26. This can explain the known scattering of data from one sample to another, irrespective of composition or layer thickness, and precludes the possibility of testing the polar-catastrophe scenario simply from inspection of ns. The Hall mobility μ (~500 cm2 V−1 s−1 at 1.5 K) and sheet resistance (~5–20 kΩ/ at room temperature) of the LASTO:x interfaces measured as a function of temperature exhibit essentially the same dependence as those for the interfaces with pure LAO films27.

at room temperature) of the LASTO:x interfaces measured as a function of temperature exhibit essentially the same dependence as those for the interfaces with pure LAO films27.

To probe experimentally the dielectric constant, capacitors were fabricated with different thicknesses of pure LAO and the x=0.5 films, using palladium as the top electrode. A serious complication in measurements of such ultrathin films is the significant contribution of the electrode–oxide interface on the capacitance28, which means that the results can only be viewed semi-quantitatively. We observe that the dielectric constants of the LASTO:0.5 and LAO display values in the range of 20 to 30, and are in good agreement with previous reports on ceramic solid-state solutions, where no large enhancement of the relative permittivity was observed for the solid solution up to 80% STO29. Measurements of the temperature dependence and the electric-field tunability confirm that LASTO:x behaves like LAO rather than STO. Cooling the films to 4 K produces a small change of the dielectric constant, in sharp contrast with the low-temperature divergence of STO. These experimental results show that there is no large enhancement of the dielectric constant in LASTO:0.5 with respect to pure LAO, as predicted by our first-principles calculations.

Fig. 3 is the central result of this work. The conductance of the interface as a function of the LASTO:x film thickness is shown for x=0.5 (Fig. 3a), x=0.75 (Fig. 3b), and x=1 (pure LAO, Fig. 3c). The conductivity is given in conductance (left axis) and/or sheet conductance (right axis). The step in conductance for x=1.0 is observed between 3 and 4 unit cells, as first observed by Thiel et al.7 and reproduced by several groups. For x=0.75 and 0.50, the data unambiguously demonstrate that the critical thickness increases with STO-content in the solid solution, with  close to 5 unit cells, and

close to 5 unit cells, and  between 6 and 7 unit cells.

between 6 and 7 unit cells.

Room-temperature conductance of LASTO:x films for (a) x=0.50, (b) x=0.75, and (c) x=1. The dashed vertical lines for x=1.0 and 0.75 indicate the experimentally determined threshold thicknesses tc, which for x=0.5, is represented by a band for the more gradual transition. All values were obtained after ensuring that the samples had remained in dark conditions for a sufficiently long time to avoid any photoelectric contributions. The blue triangles are samples belonging to the first set, and red points denote samples from second set. For details regarding the growth conditions of the two sets, see Methods.

Discussion

The striking result shown in Fig. 3 demonstrates that the critical thickness depends on x, increasing as the formal polarization decreases. The thresholds in conductivity obtained from the experimental data are only very marginally smaller than predicted by theory, which can easily be attributed to the uncertainty in the dielectric constants of the solid solutions. The overall agreement, however, with the predictions of the intrinsic polar-catastrophe model described by equation (1) is remarkable.

In contrast, it is difficult, or, at least, it demands a significantly more complex model, to explain the observed dependence of the threshold thickness with x in terms of the extrinsic phenomena of interfacial intermixing or oxygen vacancies. It would require that the 'correct' composition to provide conductivity is only achieved at the interface, regardless of the film composition, and that this stoichiometry is obtained only after depositing a film thickness that does depend on x. We can envisage no such scenario explained by intermixing or oxygen vacancies. Using the principle of Occam's razor, we therefore consider both extrinsic mechanisms to be far less plausible candidates.

In conclusion, we have shown that, in heterostructures of ultrathin films of the solid solution (LaAlO3)x(SrTiO3)1−x grown on (001) SrTiO3, the critical thickness, at which conductivity is observed, scales with the strength of the built-in electric field of the polar material. These results test the fundamental predictions of the polar-catastrophe scenario and provide compelling evidence in favour of the intrinsic origin of the doping at the LAO/STO interface.

Methods

Sample preparation

Two independent series of LASTO:x films were prepared by PLD using different sets of growth parameters. The first set of films, produced at the Paul Scherrer Institut, was grown on (001) STO substrates using two different PLD sintered targets, with x=0.50 and 0.75. Neither target (>85% dense) was conducting. Growth conditions using 266-nm Nd:YAG laser radiation were: pulse energy=16 mJ (≈2 J cm−2), 10 Hz; T=750 °C,  mbar; sample cooled after growth at 25 °C min−1 and post-annealed for 1 h in 1 atm. O2 at 550 °C. The second set of films was grown at the University of Geneva using standard growth conditions: KrF laser (248 nm) with a pulse energy of 50 mJ (≈0.6 J cm−2), 1 Hz; T=800 °C,

mbar; sample cooled after growth at 25 °C min−1 and post-annealed for 1 h in 1 atm. O2 at 550 °C. The second set of films was grown at the University of Geneva using standard growth conditions: KrF laser (248 nm) with a pulse energy of 50 mJ (≈0.6 J cm−2), 1 Hz; T=800 °C,  mbar; sample cooled after growth to 550°C in 200 mbar O2 and maintained at this temperature and pressure for 1 h before being cooled to room temperature in the same atmosphere. Both the annealing conditions produced fully oxidized films and interfaces, and were far away from the low-temperature conditions known to produce interfacial conductivity via oxygen diffusion driven by redox reactions30. The stoichiometries of the films from both sets were shown by Rutherford backscattering to be equal to the nominal PLD-target compositions of 0.5 and 0.75 to within the experimental accuracy of 1.5%.

mbar; sample cooled after growth to 550°C in 200 mbar O2 and maintained at this temperature and pressure for 1 h before being cooled to room temperature in the same atmosphere. Both the annealing conditions produced fully oxidized films and interfaces, and were far away from the low-temperature conditions known to produce interfacial conductivity via oxygen diffusion driven by redox reactions30. The stoichiometries of the films from both sets were shown by Rutherford backscattering to be equal to the nominal PLD-target compositions of 0.5 and 0.75 to within the experimental accuracy of 1.5%.

First-principles calculations

First-principles calculations were performed in the framework of density-functional theory. The electronic system was described using the so-called B1-WC hybrid functional31, which mixes the GGA functional of Wu and Cohen32 with 16% of exact-exchange within the B1 scheme33, and is known to be particularly accurate for the description of the electronic properties and structure of the LAO/STO interface23,34. Calculations were performed using the linear-combination of atomic orbitals method implemented in the CRYSTAL code35. We used localized Gaussian-type basis sets including polarization orbitals and considered all the electrons for Ti36, O37 and Al38. For Sr, we used a Hartree-Fock pseudopotential37. For La, we used the Stuttgart energy-consistent pseudopotential39. The basis sets of Sr and O were optimized for SrTiO3. In the basis set of La, Gaussian exponents smaller than 0.1 were disregarded and the remaining outermost polarization exponents for the 10s, 11s shells (0.5672, 0.2488), 9p, 10p shells (0.5279, 0.1967), and 5d, 6d, 7d shells (2.0107, 0.9641, 0.3223), together with Al 4sp (0.1752) exponent from the 8-31G Al basis set, were optimized for LaAlO3. The Brillouin zone integrations were performed using a 12×12×12 mesh of k points for the five-atom unit cell. For LASTO: x in 20-atom supercells and for STO/LAO/vacuum stacks (all doubled and rotated 90° in plane), we used a 4×4×3 points-grid and a 4×4×1 points-grid, respectively. The self-consistent-field calculations were converged until the energy changes between interactions were smaller than 10−8 Hartree. An extra-large predefined pruned grid consisting of 75 radial points and 974 angular points was used for the numerical integration of charge density. Structural optimizations were performed until they reached together thresholds of 3×10−5 Hartree/Bohr on the root-mean square values of forces and of 1.2×10−4 Bohr on the root-mean-square values of atomic displacements. The level of accuracy in evaluating the Coulomb and exchange series is controlled by five parameters35: the values used in our calculations are 7, 7, 7, 7, and 14.

For pure bulk compounds in the cubic perovskite structure, this approach yields a lattice constant and static dielectric constant for STO (aSTO=3.88 Å,  ) and LAO (aLAO=3.80 Å,

) and LAO (aLAO=3.80 Å,  ) in good agreement with experimental data at room temperature (

) in good agreement with experimental data at room temperature ( ,

,  ). When the in-plane lattice constant of LAO is expanded to that of STO to accommodate the epitaxial strain, the c-parameter contracts as expected from elastic theory, yielding co=3.75 Å (co/a = 0.97) and the dielectric constant becomes anisotropic:

). When the in-plane lattice constant of LAO is expanded to that of STO to accommodate the epitaxial strain, the c-parameter contracts as expected from elastic theory, yielding co=3.75 Å (co/a = 0.97) and the dielectric constant becomes anisotropic:  . The static dielectric constant combines a frozen-ion electronic part (that is, the optical dielectric constant

. The static dielectric constant combines a frozen-ion electronic part (that is, the optical dielectric constant  ) and a relaxed-ion phonon contribution through the expression

) and a relaxed-ion phonon contribution through the expression

where the sum runs over the transverse optic modes TOm, Ω0 is the unit-cell volume, Smij is the oscillator strength of mode m and ωm its frequency (Table 1).

To estimate theoretically the static dielectric constant of (LaAlO3) x(SrTiO3)1−x solid solutions for x=0.5 and x=0.75, we adopted a supercell approach and considered different atomic orderings as illustrated in Fig. 4. The in-plane lattice constant of the supercell was fixed to aSTO=3.88 Å. Periodic boundary conditions were used: the atomic positions and the out-of-plane lattice parameter c (along z) were relaxed and the electronic and phonon contributions to the dielectric constant were computed.

Four configurations for x=0.5 and one for x=0.75 were considered. The static dielectric constant along z,  , and the difference of energy ΔE (in eV/f.u. of 5 atoms) with respect to the reference energy Eref=xELAO+(1−x)ESTO corresponding to the sum of the individual energy of bulk LAO and STO in the same strain conditions, are summarized in Table 2.

, and the difference of energy ΔE (in eV/f.u. of 5 atoms) with respect to the reference energy Eref=xELAO+(1−x)ESTO corresponding to the sum of the individual energy of bulk LAO and STO in the same strain conditions, are summarized in Table 2.

For x=0.5, four different atomic arrangements, compatible with a 20-atom-supercell, were considered (Fig. 4). The 'checkerboard' (CB) configuration corresponds to the case in which Al and Ti atoms at the B site, and La and Sr atoms at the A site, are perfectly alternating along the three Cartesian directions of the cubic perovskite unit cell; it is the atomic configuration most representative of a perfect mixing achievable within the chosen supercell. The 'chain' configurations then preserve Ti and Al chains (for C1) and Ti and Al and Sr and La chains (for C2) along the z direction; these configurations mimic arrangements in which columns of STO and LAO are in parallel. Finally, the 'planar' configuration (P1) corresponds to a STO/LAO 1/1 superlattice in which STO and LAO planes alternate along the z direction, and therefore corresponds to having STO and LAO in series.

In all cases, the static dielectric constant along z remains close to that of LAO under the same strain conditions ( ). In the CB configuration, we obtain

). In the CB configuration, we obtain  . For the P1 arrangement, we also nearly recover the dielectric constant of LAO, as expected when putting LAO and STO in series, while the dielectric constant increases for C1 and C2, as expected when placing them in parallel. All these results are compatible with the fact that the large dielectric constant of STO arises from the contribution of the low-frequency ferroelectric mode, which requires a correlation of the atomic displacement along Ti-O chains, which is suppressed by atomic disorder.

. For the P1 arrangement, we also nearly recover the dielectric constant of LAO, as expected when putting LAO and STO in series, while the dielectric constant increases for C1 and C2, as expected when placing them in parallel. All these results are compatible with the fact that the large dielectric constant of STO arises from the contribution of the low-frequency ferroelectric mode, which requires a correlation of the atomic displacement along Ti-O chains, which is suppressed by atomic disorder.

The C1 and C2 orderings exhibit the highest dielectric constants and have the highest energies; these are, therefore, unlikely to appear spontaneously. The energetically most stable configuration is P1. However, as the growth is not at thermodynamic equilibrium and there is no experimental evidence from X-ray diffraction of any kind of spontaneous superlattice ordering, we consider the theoretical configuration most representative of the experimentally grown system to be the CB ordering, which exhibits a static dielectric constant nearly equal to that of LAO. We notice that averaging over the different orderings would still produce a dielectric constant close to that of LAO. This conclusion is further confirmed experimentally.

On the basis of these findings, we subsequently modelled STO/(LASTO:0.5)m/vacuum stacks, considering the CB atomic arrangement. First, before breakdown, the computed electric field within LASTO:0.5 is equal to about 0.1 V Å−1, roughly half that observed in pure LAO (0.24 V Å−1) and consistent with the fact that the dielectric constant remains approximately the same, whereas the formal polarization is half that of pure LAO. The average lattice constant within LASTO:0.5 is equal to 3.84 Å, slightly larger than the value of 3.81 Å for CB bulk LASTO:0.5 in the same strain conditions, consistent with the electrostrictive effect. This value is comparable to what is measured experimentally. Increasing m, the first-principles calculations predict that the system becomes metallic for m between 6 and 7, in perfect agreement with the polar catastrophe scenario and the experimental measurements.

For x=0.75, we considered the atomic arrangement of configuration M in Fig. 4, that corresponds to a checkerboard arrangement in plane. Here again the static dielectric constant of the alloy remains essentially equal to that of LAO:  .

.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Reinle-Schmitt, M.L. et al. Tunable conductivity threshold at polar oxide interfaces. Nat. Commun. 3:932 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1936 (2012).

References

Okamoto, S. & Millis, A. J. Electronic reconstruction at an interface between a Mott insulator and a band insulator. Nature 428, 630–633 (2004).

Ohtomo, A. & Hwang, H. Y. A high-mobility electron gas at the LaAlO3/SrTiO3 heterointerface. Nature 427, 423–426 (2004).

Gozar, A. et al. High-temperature interface superconductivity between metallic and insulating copper oxides. Nature 455, 782–785 (2008).

Zubko, P., Gariglio, S., Gabay, M., Ghosez, P. & Triscone, J.- M. Interface physics in complex oxide heterostructures. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2, 141–165 (2011).

Hwang, H. Y. et al. Emergent phenomena at oxide interfaces. Nat. Mater. 11, 103–113 (2012).

Nakagawa, N., Hwang, H. Y. & Muller, D. A. Why some interfaces cannot be sharp. Nat. Mater. 5, 204–209 (2006).

Thiel, S., Hammerl, G., Schmehl, A., Schneider, C. W. & Mannhart, J. Tunable quasi-two-dimensional electron gases in oxide heterostructures. Science 313, 1942–1945 (2006).

Schlom, D. G. & Mannhart, J. Oxide electronics: interface takes charge over Si. Nat. Mater. 10, 168–169 (2011).

Huijben, M. et al. Electronically coupled complementary interfaces between perovskite band insulators. Nat. Mater. 5, 556–560 (2006).

Cancellieri, C. et al. Influence of the growth conditions on the LaAlO3/SrTiO3 interface electronic properties. Europhys. Lett. 91, 17004 (2010).

Popovic, Z. S., Satpathy, S. & Martin, R. M. Origin of the two-dimensional electron gas carrier density at the LaAlO3 on SrTiO3 interface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 256801 (2008).

Lee, J. & Demkov, A. A. Charge origin and localization at the n-type SrTiO3/LaAlO3 interface. Phys. Rev. B 78, 193104 (2008).

Siemons, W. et al. Origin of charge density at LaAlO3 on SrTiO3 heterointerfaces: Possibility of intrinsic doping. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 196802 (2007).

Herranz, G. et al. High mobility in LaAlO3/SrTiO3 heterostructures: Origin, dimensionality and perspectives. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 216803 (2007).

Kalabukhov, A. et al. Effect of oxygen vacancies in the SrTio3 substrate on the electrical properties of the LaAlO3/SrTiO3 interface. Phys. Rev. B 75, 121404(R) (2007).

Bristowe, N. C., Littlewood, P. B. & Artacho, E. Surface defects and conduction in polar oxide heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 83, 205405 (2011).

Xie, Y., Hikita, Y., Bell, C. & Hwang, H. Y. Control of electronic conduction at an oxide heterointerface using surface polar adsorbates. Nat. Commun. 2, 494 (2011).

Willmott, P. R. et al. Structural basis for the conducting interface between LaAlO3 and SrTiO3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 155502 (2007).

Qiao, L. et al. Thermodynamic instability at the stoichiometric LaAlO3/SrTiO3 (001) interface. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 22, 312201 (2010).

Qiao, L. et al. Epitaxial growth, structure, and intermixing at the LaAlO3/SrTiO3 interface as the film stoichiometry is varied. Phys. Rev. B 83, 085408 (2011).

Segal, Y., Ngai, J. H., Reiner, J. W., Walker, F. J. & Ahn, C. H. X-ray photoemission studies of the metal-insulator transition in LaAlO3/SrTiO3 structures grown by molecular beam epitaxy. Phys. Rev. B 80, 241107 (2009).

Pauli, S. A. et al. Evolution of the interfacial structure of LaAlO3 on SrTiO3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 036101 (2011).

Cancellieri, C. et al. Electrostriction at the LaAlO3/SrTiO3 interface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 056102 (2011).

Stengel, M. & Vanderbilt, D. Berry-phase theory of polar discontinuities at oxide-oxide interfaces. Phys. Rev. B 80, 241103 (2009).

Konaka, T., Sato, M., Asano, H. & Kubo, S. Relative permittivity and dielectric loss tangent of substrate materials for high-t c superconducting film. J. Superconduct. 4, 283–288 (1991).

Bert, J. A. et al. Direct imaging of the coexistence of ferromagnetism and superconductivity at the LaAlO3/SrTiO3 interface. Nat. Phys. 7, 767–771 (2011).

Gariglio, S., Reyren, N., Caviglia, A. D. & Triscone, J.- M. Superconductivity at the LaAlO3/SrTiO3 interface. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 164213 (2009).

Stengel, M. & Spaldin, N. A. Origin of the dielectric dead layer in nanoscale capacitors. Nature 443, 679–682 (2006).

Sun, P. H. et al. Dielectric behavior of (1-x)LaAlO3 xSrTiO3 solid solution system at microwave frequencies. Jap. J. Appl. Phys. 37, 5625–5629 (1998).

Chen, Y. et al. Metallic and insulating interfaces of amorphous SrTiO3-based oxide heterostructures. Nano Lett. 11, 3774–3778 (2011).

Bilc, D. I. et al. Hybrid exchange-correlation functional for accurate prediction of the electronic and structural properties of ferroelectric oxides. Phys. Rev. B 77, 165107 (2008).

Wu, Z. & Cohen, R. E. More accurate generalized gradient approximation for solids. Phys. Rev. B 73, 235116 (2006).

Becke, A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. IV. A new dynamical correlation functional and implications for exact-exchange mixing. J. Chem. Phys. 104, 1040–1046 (1996).

Delugas, P. et al. Spontaneous 2-dimensional carrier confinement at the n-type SrTiO3/LaAlO3 interface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 166807 (2011).

Dovesi, R. et al. CRYSTAL: a computational tool for the ab initio study of the electronic properties of crystals. Z. Kristallogr. 220, 571–573 (2005).

Bredow, T., Heitjans, P. & Wilkening, M. Electric field gradient calculations for LixTiS2 and comparison with 7Li NMR results. Phys. Rev. B 70, 115111 (2004).

Piskunov, S., Heifets, E., Eglitis, R. I. & Borstel, G. Bulk properties and electronic structure of SrTiO3, BaTiO3, PbTiO3 perovskites: an ab initio HF/DFT study. Comp. Mat. Sci. 29, 165–178 (2004).

Towler, M. CRYSTAL resource page, 2011, see www.tcm.phy.cam.ac.uk/~mdt26/crystal.html.

Cao, X. Y. & Dolg, M. Segmented contraction scheme for small-core lanthanide pseudopotential basis sets. J. Mol.. Struct. Theochem. 581, 139–147 (2002).

Acknowledgements

Support of this work by the Schweizerischer Nationalfonds zur Förderung der wissenschaftlichen Forschung, in particular the National Center of Competence in Research, Materials with Novel Electronic Properties, MaNEP, and by the European Union through the project OxIDes is gratefully acknowledged. We also thank Dr. Max Döbeli for the RBS measurements and Dr. Pavlo Zubko for assistance in the capacitance measurements. Ph.G. is grateful to the Francqui Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Project was conceived by P.R.W. Film growth was carried out by M.L.R.-S., C.C., D.L., and C.W.S. The deposition target was synthesized by E.P. X-ray diffraction and RHEED measurements were performed by M.L.R.-S., C.C, and C.W.S. Electrical characterizations were performed by M.L.R.-S., C.C., D.L., M.M., and S.G. Theoretical calculations were carried out by D.F. and Ph.G. All authors contributed to interpretation of the results and writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reinle-Schmitt, M., Cancellieri, C., Li, D. et al. Tunable conductivity threshold at polar oxide interfaces. Nat Commun 3, 932 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1936

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1936

This article is cited by

-

Capping layers and their roles in polar catastrophe scenario of LaAlO3/SrTiO3 (001) systems

Journal of the Korean Physical Society (2022)

-

Tuning two-dimensional electron and hole gases at LaInO3/BaSnO3 interfaces by polar distortions, termination, and thickness

npj Computational Materials (2021)

-

Aperiodic quantum oscillations in the two-dimensional electron gas at the LaAlO3/SrTiO3 interface

npj Quantum Materials (2020)

-

Current vortices and magnetic fields driven by moving polar twin boundaries in ferroelastic materials

npj Computational Materials (2020)

-

A termination-insensitive and robust electron gas at the heterointerface of two complex oxides

Nature Communications (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.