Abstract

The success of van der Waals heterostructures made of graphene, metal dichalcogenides and other layered materials, hinges on the understanding of charge transfer across the interface as the foundation for new device concepts and applications. In contrast to conventional heterostructures, where a strong interfacial coupling is essential to charge transfer, recent experimental findings indicate that van der Waals heterostructues can exhibit ultrafast charge transfer despite the weak binding of these heterostructures. Here we find, using time-dependent density functional theory molecular dynamics, that the collective motion of excitons at the interface leads to plasma oscillations associated with optical excitation. By constructing a simple model of the van der Waals heterostructure, we show that there exists an unexpected criticality of the oscillations, yielding rapid charge transfer across the interface. Application to the MoS2/WS2 heterostructure yields good agreement with experiments, indicating near complete charge transfer within a timescale of 100 fs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Charge transfer is a fundamental process governing numerous biological, chemical and physical systems. Electrons or holes transferred to different regions or functional groups can trigger chemical reactions and are integral to phenomena such as photosynthesis and water splitting1,2. In heterostuctures, which are a basic platform for solid-state applications such as solar cells, light-emitting diodes and high-mobility transistors3,4,5, charge transfer controls electron–hole recombination and hence plays a crucial role in device operation6,7. While the structure of traditional (covalent) heterostructures are limited by the stringent requirement of lattice matching between constituent materials to avoid defect formation and large strain at the interface8, the severity of such issues are greatly diminished in the emerging van der Waals (vdW) heterostructures consisting of two-dimensional atomic crystals9,10,11. The vdW heterostructures are very promising as their components can be chosen from a variety of systems, such as graphene, hexagonal boron nitride, transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), phosphorene and silicene. These atomically thin materials present a set of attractive physical properties such as high thermal and electrical conductivity12, Klein tunnelling13, valleytronics14,15,16, strong absorption of light17 and strong photoluminescence17,18,19. For vdW interfaces, one may expect that the component materials are relatively isolated from each other maintaining their individual properties because the interfacial vdW spacing is considerably wider than a covalent or ionic chemical bond, and hence electronic coupling between the layers is expected to be weak. This presumed weak coupling has motivated recent proposals for using such materials for photovoltaic and diode-like current rectification applications20,21,22,23. This makes the recent findings of photoluminescence and femtosecond pump-probe spectroscopy experiments20,24 that the charge transfer in MoS2/WS2 is an ultrafast phenomena (within 100 fs) quite surprising. Similarly, fast charge transfer has also been observed for the MoS2/MoSe2 heterostructure22, suggesting that in these new heterostructures, the physics of charge transfer may fundamentally depart from traditional pictures of non-coherent charge transfer25,26,27. Developing a basic understanding of the mechanisms of charge transfer across the vdW hetostructure is not only of fundamental interest but essential for the successful application of these materials.

In this work, time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) is combined with molecular dynamics (MD) to understand the physics governing the ultrafast hole transfer from MoS2 to WS2. We find that significant hole transfer takes place within a timescale of 100 fs of the initial excitation in agreement with experiments20,24. Although conventional wisdom suggests that throughout this process accumulated holes would lead to a dipole that would tend to hamper further hole transfer—our analysis of quantum states dynamics during the transfer process suggests precisely the opposite. Our study reveals a strong dynamic coupling, whereby charge transfer across the heterostructure significantly increases the coupling between the hole states in MoS2 and WS2. It follows that after an initial induction time of relatively slow charge transfer, the charged dipole layer causes the rapid transfer of holes across the heterostructure despite the fact that the internal electric field opposes the direction of hole transfer. A model for the hole transfer shows that this mechanism is critically dependent on the magnitude of the dipole transition matrix element, which determines the coupling across the heterostructure. As a result, the existence of ultrafast charge transfer is sensitive to the atomistic details of the interface, in particular the heterostructure stacking. While the energetically favourable 2H stacking (in which the S atoms of WS2 lie directly above Mo) is found to exhibit ultrafast charge transfer, dipole coupling in 3R and AB′ stacking configurations28,29 (in which the W atom of WS2 lies directly above S or Mo from MoS2, respectively) is found to remain below the minimum threshold, resulting in much slower charge transfer.

Results

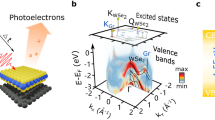

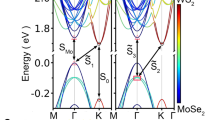

Real-time TDDFT-MD

To investigate the photo-induced charge transfer dynamics at the MoS2/WS2 interface, we built a structural model and setup similar to the experimental situation20,24, see Fig. 1a, to choose an initial occupation of electrons associated with the optical excitation, and simultaneously iterate the combined electron and ionic dynamics using time domain TDDFT-MD (see the Methods section). The appropriate initial excitation is determined through examination of the band structure shown in Fig. 1b. We find that the gap is indirect with the valence band maximum (VBM), in which the wave function is delocalized to both WS2 and MoS2, at Γ and the conduction band minimum (CBM), in which the wave function is localized to MoS2, at the K-point of the Brillouin zone, consistent with previous findings17,30. In the vicinity of the K-point, shown in the blue rectangle and enlarged in Fig. 1c, a type-II alignment develops where the local VBM, which we denote |WS2〉 presents a charge density almost entirely localized to WS2. Conversely, the state immediately below the VBM, the (VBM-1) state, is almost entirely localized to MoS2 and is denoted by |MoS2〉 in Fig. 1c. As optical absorption via the indirect transition (VBM→CBM) or involving charge transfer across the interface (VBM(at K)→CBM) is negligible24,30, the predominate optical absorption is associated with the direct excitation of electrons from the (VBM-1) state to the CBM in the vicinity of K, as indicated by the red arrow in Fig. 1c. The subsequent hole transfer observed in the experiment20,24 results from the type-II alignment, whereby the holes can substantially reduce their energy by transferring from |MoS2〉 to |WS2〉, as indicated by the blue arrow in Fig. 1c. Hence, in the TDDFT-MD simulation, two electrons were excited from the |MoS2〉 state to the CBM and our subsequent analysis focuses on the hole dynamics.

(a) Illustration of the heterostructure, where a WS2 monolayer lies on top of a MoS2 monolayer. Electron and hole carriers excited by incident light separate by hole transfer into the WS2. (b) Band structure of the heterostructure, showing an indirect bandgap from Γ to K. The smallest direct transition with appreciable absorption is from the (VBM-1) state to the CBM in the vicinity of K. (c) Band structure in the vicinity of K-point in the Brillouin zone. From the K-point at the centre, right and left are directions toward Γ and M points, respectively. The incident light excites electron in |MoS2〉 to the conduction band minimum, and hole is transferred into |WS2〉. The energy of the valence band maximum at the K-point is set to zero. Colour indicates the degree of projection of each state onto the MoS2 layer. A projection of one (pink) indicates complete localization of the state to the MoS2 layer and that of zero (blue) indicates localization to the WS2 layer. (d,e) Isosurface plots of two valence band charge density at the K-point. The local VBM, which we denote |WS2〉, presents almost entirely localized charge to WS2 (d), but the (VBM-1) state, which we denote|MoS2〉, is almost entirely localized to MoS2 (e).

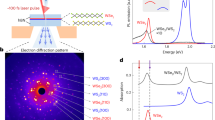

Figure 2a–c shows the time evolution of the hole (h) occupation ρh, calculated by projecting the time-evolved hole wave function ϕ(t) onto |MoS2〉 and |WS2〉, that is, ρh(MoS2)=|〈MoS2|ϕ(t)〉|2 and ρh(WS2)=|〈WS2|ϕ(t)〉|2, for the case of 2H stacking at the three different ionic temperatures, T=0, 77 and 300 K, respectively. Let us first consider the case of 77 K. Figure 2b shows that ρh oscillates by periodically filling and emptying |MoS2〉 and |WS2〉 states at a period of approximately 30 fs, albeit with a damped amplitude. The decay of the ρh(MoS2) is significant, indicating that the average hole position is transitioning in time, from being primarily localized on |MoS2〉 to reside on either side of the interface, with nearly equal probability. As the energy of the hole is lower in |WS2〉 than in |MoS2〉, as shown in Fig. 1c, this change in expectation value for the hole position is associated with an energy relaxation process—wherein excitation energy of the hole is being dissipated by phonons throughout the transition. The same effect, although even more pronounced, is also observed at 300 K, as shown in Fig. 2c. To investigate which phonons are associated with the decay process, we determine the energy of each normal mode of the system as a function of time, as shown for several time snapshots throughout the 77 K simulation in Fig. 3a–d. Here it can be seen that the A1g Raman active modes and phonons associated with the longitudinal acoustic branch with non-zero wavevectors pick up substantial energy in the decay process. In particular, the strong coupling of the two A1g phonon modes, involving out-of-plane vibrations of S atoms shown in Fig. 3e, is due to the large associated modification of the distance between the vdW layers. It follows that these modes present a large response to a transverse electric field associated with charge transfer as evidenced by the substantial peaks of the A1g modes in the Raman spectra of MoS2 and WS2 (refs 31, 32). While the longitudinal acoustic phonons also show a marked increase in energy at approximately 120 fs, we note that this may be due to subsequent phonon–phonon relaxation of the higher energy A1g modes.

The hole occupations ρh(MoS2) and ρh(WS2) are shown in pink and blue, respectively, as a function of time for the three separate TDDFT-MD simulations with 2H stacking: (a) the clamped ion case (b) mobile ions at a temperature of 77 K and (c) mobile ions at a temperature of 300 K. For the clamped ion case (a), we see large periodic oscillations in the hole occupation which are not associated with the ionic dynamics of the system. For the finite temperature cases (b,c), the average occupations of the hole for each period are indicated by a set of points which are connected by a dashed line as a guide to the eye. As time progresses, the average hole occupation of |WS2〉 increases and the average hole occupation of |MoS2〉 decreases, indicating charge transfer via dissipation through electron-phonon coupling. (d) The dynamics of the hole occupation of the model Hamiltonian presented in equation (2), where the parameters used are indicated in Table 1. The model well produces the oscillations seen in the fixed ion case (a). By fitting the coupling of the model to a heat bath containing a receiving mode at 400 cm−1, the qualitative features of the hole dynamics for both the 77 and 300 K can be qualitatively reproduced as shown in e,f, respectively.

This depicts the increase in energy of every vibrational mode of the system as a function of time throughout the TDDFT-MD dynamics of the 77 K simulation. The total energy of each normal mode is indicated at 30, 60, 90 and 120 fs in panel (a–d), respectively. The four normal modes which pick up the largest amount of energy throughout the simulation are labelled (I), (II), (III) and (IV) with mode numbers of 420, 471, 149 and 153 and corresponding frequencies 415, 400, 214 and 215 cm−1, respectively. The displacement eigenvectors associated with these normal modes are depicted by the blue arrows shown in e. On the basis of the frequencies and vibrational motion shown in e, out-of-plane oscillations of S atoms for (I) and (II), these two phonon modes clearly correspond to the A1g Raman mode of the MoS2 layer and A1g Raman mode of the WS2 layer, respectively. Note that the A1g mode is one of the most prominent Raman modes in TMDs32,45, indicating strong electron-phonon coupling for A1g phonons. Similarly, the modes labelled (III) and (IV) correspond to longitudinal acoustic (LA) phonons with non-zero wavevector. Notably, phonons from the LA branch at the M point have been found to exhibit appreciable signals in the resonant Raman scattering, also suggesting strong electron-phonon coupling for LA phonons31.

To better understand the hole dynamics and the role of phonons in the charge transfer process, we decouple the ionic motion from the hole dynamics by performing a TDDFT simulation where the ionic positions are frozen throughout the simulation, as shown in Fig. 2a. The large charge sloshing and the lack of amplitude dampening here are further evidence that it is indeed the electron–phonon coupling that is responsible for the dissipation. In addition, it confirms that the observed hole oscillation is not the result of ionic motion. Interestingly, the oscillation is not sinusoidal as one would expect from a superposition of the two states, |MoS2〉 and |WS2〉, but rather it can be characterized by broad mesas with sharp peaks. This indicates that the coupling between |MoS2〉 and |WS2〉, which governs the characteristic frequency of oscillation, gains time dependence throughout the simulation; initially being quite small and becoming more substantial near the peaks. Furthermore this dynamic coupling is purely an electronic phenomenon and is not associated with the ionic vibration, since these were kept fixed throughout this simulation. As such, the mechanism for coherent charge oscillations here are distinct from those proposed for organic photovoltaic blend33 and artificial light-harvesting system34, wherein the charge oscillations are associated with the frequency of a vibrational mode of the system. To understand the mechanism giving rise to the nonlinear charge oscillations, time-dependent coupling and ultimately the ultrafast charge transfer in the vdW heterostructure, we now further examine the electron dynamics of the system.

Mechanism for ultrafast coherent charge oscillations

Much insight can be gained on the mechanism for the coherent charge oscillations by considering the excitation-induced interfacial dipole and its time evolution, as shown in Fig. 4a. While the origin of this oscillating interfacial dipole is hole transfer from |MoS2〉 to |WS2〉, here it should be noted the importance of the collective behaviour of the holes during transport. To mimic the coherent excitation associated with a pump laser setup,20 the initial conditions of the TDDFT-MD simulation contain two holes with identical characteristics. Throughout the course of simulation, they maintain identical characteristics with both single-particle hole wavefunctions evolving identically in time. Furthermore, the periodic boundary conditions represent an entire sheet of charges, and as a result charge transfer from MoS2 to WS2 is associated with the collective motion of holes across the interface with a resulting macroscopic dipole similar to the parallel plate capacitor schematically shown in Fig. 4b. As this macroscopic dipole is responsible for modulating the hole dynamics, tests indicate that for slightly different initial hole character, the results do not alter qualitatively. While the E-field produced in this manner opposes hole transfer from MoS2 to WS2, it significantly enhances the coupling between the two states and hence alters the characteristic timescale of the oscillations.

(a) The difference in the total dipole calculated throughout the TDDFT-MD simulation of the hole dynamics with fixed ionic positions and the dipole of the ground-state heterostructure, as a function of time. The sharp peaks in the dipole moment correspond to peaks in the hole occupation on WS2 seen in Fig. 2a,b Schematic illustration of a simple parallel plate capacitor view of the heterostructure. Excess charge density σ caused by the charge transfer induces electric field  between the plates.

between the plates.

This phenomenon can be understood in the context of an elementary model where a single hole exists in a two-state system (either in MoS2 or WS2) in the presence of an external electric field representing the hole’s interaction with the dipole generated by the other holes in the system. Assuming the geometry shown in Fig. 4b, the Hamiltonian associated with the uniform E-field in the z-direction, perpendicular to the interface,

where E0 is the initial magnitude of the z-component of the electric field associated with charge rearrangement due to the optical excitation and  is the time-dependent field, which is dynamically generated due to hole transport from MoS2 to WS2. Using the ground-state eigenfunctions |WS2〉 and |MoS〉 as basis and choosing the origin between the two slabs, the Hamiltonian of the two-state system in the external field becomes,

is the time-dependent field, which is dynamically generated due to hole transport from MoS2 to WS2. Using the ground-state eigenfunctions |WS2〉 and |MoS〉 as basis and choosing the origin between the two slabs, the Hamiltonian of the two-state system in the external field becomes,

where  and

and  are the hole energies of the ground-state eigenfunctions of the heterostructure, d is the effective distance between the two layered materials, seen here as two plates of the capacitor, d=(〈WS2|z|WS2〉−〈MoS2|z|MoS2〉), and Mz is the magnitude of the z-component of the dipole transition matrix element between the heterostructures, 〈WS2|z|MoS2〉. Here it can be seen that the electric field contributes to both the diagonal and off-diagonal matrix elements. While the diagonal ones reduce the energy difference between the two levels that drive hole transfer, the off-diagonal elements increase the dipole coupling between the MoS2 and WS2 states. In principle, all of the parameters in equation (2) can be calculated with first principles methods, however, as the 2 × 2 model Hamiltonian is significantly reduced from the full Hamiltonian of the actual system, several parameters are obtained by fitting to the TDDFT-MD results. The good agreement between the model Hamiltonian with the TDDFT-MD results using fitted values for d, ɛ and E0 establishes the validity of the approach, as shown in Fig. 2d. Notably, instead of a sinusoidal oscillation of ρh, the model correctly predicts the sharp peaks and broad mesas observed in the TDDFT-MD simulations. The ability for such a simple model to capture the nonlinear behaviour present in the TDDFT-MD results and the closeness of the fit parameters to those calculated via first principles (Table 1) validate the physical arguments used to derive it.

are the hole energies of the ground-state eigenfunctions of the heterostructure, d is the effective distance between the two layered materials, seen here as two plates of the capacitor, d=(〈WS2|z|WS2〉−〈MoS2|z|MoS2〉), and Mz is the magnitude of the z-component of the dipole transition matrix element between the heterostructures, 〈WS2|z|MoS2〉. Here it can be seen that the electric field contributes to both the diagonal and off-diagonal matrix elements. While the diagonal ones reduce the energy difference between the two levels that drive hole transfer, the off-diagonal elements increase the dipole coupling between the MoS2 and WS2 states. In principle, all of the parameters in equation (2) can be calculated with first principles methods, however, as the 2 × 2 model Hamiltonian is significantly reduced from the full Hamiltonian of the actual system, several parameters are obtained by fitting to the TDDFT-MD results. The good agreement between the model Hamiltonian with the TDDFT-MD results using fitted values for d, ɛ and E0 establishes the validity of the approach, as shown in Fig. 2d. Notably, instead of a sinusoidal oscillation of ρh, the model correctly predicts the sharp peaks and broad mesas observed in the TDDFT-MD simulations. The ability for such a simple model to capture the nonlinear behaviour present in the TDDFT-MD results and the closeness of the fit parameters to those calculated via first principles (Table 1) validate the physical arguments used to derive it.

Investigating how the model describes the physics of charge transfer as a function of Mz, we find that criticality exists and that the hole dynamics undergoes a qualitative change depending on the magnitude of the dipole-induced coupling. Keeping the initial electric field associated with the excitation fixed at 6.9 mV Å−1, the maximum amount of dynamic hole transfer as a function of the magnitude of the dipole coupling Mz is shown in Fig. 5a. For small coupling, this serves to mix the two states leading to small sinusoidal oscillations associated with being in a linear superposition of states. However, after the coupling reaches a critical value, at approximately 1.05 Å, the magnitude of this oscillation changes discontinuously from below 5% to above 75% of the hole population. The emergence of this discontinuity is a result of the inherent non-linearity of the Hamiltonian. Through numerical investigation, we find that the effective potential that governs the dynamics of ρh is bimodal. For small values of Mz, the system does not have enough energy to overcome the barrier separating the two wells and the system dynamics are trapped, yielding only small values of ρh and minimal charge transfer. As Mz is increased, however, the barrier separating the two wells decreases, until the critical value in which the system dynamics can overcome the barrier leading to much larger oscillations in ρh. Physically, beyond this critical value, despite the initial small coupling, the collective behaviour of the holes in the system leads to feedback so that the degree of hole transfer is enough to steadily increase the coupling leading to even more charge transfer. This critical dependence on Mz highlights the importance of the interlayer spacing (and vdW interaction) on the ultrafast charge-transfer mechanism. Note that the existence of substantial dipole coupling, Mz=〈MoS2|z|WS2〉, relies on the spatial overlap of the |MoS2〉 and |WS2〉 wavefunctions. Hence, the nature and strength of vdW interaction at the interface, which determines the distance between layers and hence the spatial overlap of the wavefunctions, becomes an essential part of the rapid charge transfer. Furthermore, as electron–phonon coupling is proportional to the magnitude of the dipole oscillation, the fast energy dissipation to phonons and ultimately the ultrafast charge transfer can be viewed as a direct result of this marked charge oscillation resulting from the prerequisite critical dipole coupling of the heterostructure.

(a) Depicts the critical nature of the charge oscillations predicted from the model as a function of the magnitude of the z-component of the dipole transition matrix element, Mz. At the critical point (approximately 1.05 Å, indicated by the dashed line), the dynamics change discontinuously wherein the maximal hole occupation of WS2 changes from approximately 0.05 to 0.75. The discontinuous nature of the dynamics with respect to Mz are apparent by examining the time evolution of ρh, shown in the panels, for values of Mz at the red points lying just to the left (II) and the right (III) of the criticality. (b) Colour map indicating the degree of charge transfer as a function of time and temperature calculated from the model interacting with a heat bath containing a receiving mode at 400 cm−1. The interaction parameter was determined via a fit to the TDDFT-MD results. (c) Colour map indicating the degree of charge transfer as a function of time and temperature, where we have gone beyond the classical picture of ions from the TDDFT-MD simulation by assigning the receiving normal mode energy corresponding to the Bose-Einstein distribution. By directly comparing b and c, we see that only as we approach room temperature do the classical and quantum pictures of ionic motion yield correspondence.

To extend the model to incorporate interaction with ionic motion, we include a mean-field interaction with a heat bath (see Methods section). Fitting the interaction parameter to a single receiving mode at 400 cm−1 leads to a qualitative agreement with the finite temperature TDDFT-MD results, as shown in Fig. 2e,f. Furthermore, this fitting allows us to calculate charge dynamics as a continuous function of temperature in Fig. 5b and improve on the TDDFT-MD results by considering the quantum mechanical nature of the ions in Fig. 5c revealing that near-complete charge transfer takes place within 100 fs even as T approaches 0 K. Figure 5b,c and almost the entirety of the results presented herein refer to the case of 2H stacking between MoS2 and WS2, which we have predicted to exhibit ultrafast hole transfer. In contrast, for the 3R and AB′ stacking configurations, we find that no hole transfer takes place from MoS2 to WS2 over the entire simulation period of 120 fs. This result is due to the critical role played by the magnitude of the dipole transition matrix element in the onset of the charge oscillations. For both the 3R and AB′ stackings, we find Mz to be far below this critical threshold, both being approximately 10−5 Å. This sensitivity to stacking is also seen in the transfer integral, where the electronic coupling of the 2H case is found to be 132 meV, many orders of magnitude larger than either the 3R or AB′ cases. This sensitivity on the atomistic details of the interface can be traced back to the C3v symmetry of the wavefunctions associated with the VBM of the isolated layers of |MoS2〉 and |WS2〉, which are shown in Fig. 6a,b, respectively. Regions of positive and negative wave function are highlighted by the red and blue triangles, respectively. Looking at the case of AB′ stacking, schematically shown in Fig. 6c, it can be seen that due to the shift in the unit cell, there is very little spatial overlap in the wave function of MoS2 (represented by the open triangles) and that of WS2 (represented by the shaded triangles). This can also be seen in the case of 3R stacking, shown in Fig. 6d, where the small overlap that does exist tends to cancel. Conversely, for 2H stacking shown in Fig. 6e, the wavefunctions line up entirely, yielding maximal spatial overlap and an associated much stronger coupling.

Plots of the wave function associated with the VBM in the vicinity of K for isolated layers of (a) |Mos2〉 and (b) |WS2〉. The plots correspond to the values of the wave function above (below) MoS2 (WS2) at what would be the interfacial plane of a combined heterostructure. Regions where the wavefunctions have a large magnitude have been highlighted by red (blue) triangles to indicate their positive(negative) values. Schematic representations of the wave function alignment between layers for the case of AB’, 3R, and 2H stackings are shown in (c–e), respectively. For the different cases, the unit cells are indicated and the wavefunctions of MoS2 (WS2) are schematically shown by the open (shaded) triangles. For the 2H stacking case, the wavefunctions line up with each other, yielding maximal spatial overlap and relatively large dipole transition matrix elements.

Discussion

The TDDFT-MD modelling was performed for the most stable 2H stacking. However, we note that experimental studies of the excited-state hole dynamics have been carried out on far less-controlled samples than the perfect stacking since it is based on mechanical pealing and transfer20. The low energy of the 2H stacking suggests that despite the nominal random stacking in experiment, either the 2H stacking dominates or the large sample size guarantees that a sufficiently large proportion of isolated regions feature 2H stacking, thereby ensuring fast charge transfer.

The model describing charge transfer in vertical MoS2/WS2 heterostructure is general and should be applicable to any weakly bound heterostructures where coupling is dominated by the induced electric field. Furthermore, as charge sloshing couples strongly to Γ-point phonons (A1g) associated with modulation of the vdW gap region, ultrafast charge transport across vdW heterostructures may be the rule rather than the exception. As the initiation of this mechanism for transport is critically dependent on the dipole coupling matrix element, this relationship deserves further study. In particular, our findings prompt a number of fundamental questions: What are the root causes of the discontinuity? What are the dynamics at the critical point? As the collective motion of holes is responsible for the criticality, can this mechanism be interpreted as the instability of an excitonic plasma at the interface? While the timescale of the predicted charge oscillations may be difficult to resolve with current experimental techniques, the mechanism for ultrafast charge transport presented here and the critical role of Mz should be confirmed either by careful preparation of heterostructures with different stacking configurations or through an assortment of vdW heterostructures that feature different intrinsic Mz. Similar to the discontinuity reproduced by the new model, it is expected that vdW heterostructures with intrinsic Mz coupling larger than Mcrit will exhibit ultrafast charge transport while those with smaller intrinsic coupling, such as 3R and AB′ stacked MoS2/WS2, will exhibit charge transport on a timescale several order of magnitudes larger.

In summary, a combined ab initio TDDFT-MD simulation and analytic modelling reveals the nature of hole transfer as a result of carriers dynamics at the MoS2/WS2 vdW heterostructures. Despite the weak interlayer vdW binding, the collective motion of the holes is found to lead to strong dynamic coupling due to the transverse electric field associated with charge transfer. In contrast to classical systems, the build-up of an interfacial dipole can serve as an enhancement factor for such an ultrafast transfer in quantum coherent systems. This ultrafast transfer is well described by a simple model Hamiltonian in which, provided the existence of a critical dipole transition matrix element, the collective motion leads to dramatic non-linear charge oscillations that couple strongly to the phonons at the Γ-point. We anticipate that these findings will trigger further fundamental studies and new device concepts over a broad range of two-dimensional layered materials and systems.

Methods

Real-time TDDFT-MD

The electron and ion dynamics are simulated within the TDDFT formalism35 coupled with MD, within the local density approximation (LDA) as implemented in the SIESTA code36,37,38. We employ Troullier–Martins norm-conserving pseudopotentials and Ceperley–Alder39 exchange-correlation functional. Local basis set with double-ζ polarized orbitals is used. The real-space grid is equivalent to a plane-wave cutoff energy of 350 Ry. A  supercell containing 162 atoms with Γ-point for the Brillouin zone integration is used. Note that the K-point of primitive cell is folded to the Γ point in this supercell. In contrast to the well-known underbinding character in the PBE functional, the LDA reproduces the experimental structural parameters quite well for the vdW systems, as shown in Table 2. Although vdW forces are not explicitly included in the LDA formalism, LDA is known to yield a good description of forces between layers in TMDs as indicated by the quantitative agreement of the layer-to-layer vibration modes in these systems, as compared with experimental Raman data31,40,41,42,43. Furthermore, LDA predicts the preference of the 2H stacking, similar to the vdW density functionals (which are built on top of semi-classical GGA functionals such as PBE)29. We consider 3R, AB′ and 2H stacking patterns for the MoS2/WS2 heterostructures28,29, but we focus our discussion on the 2H stacking patterns in this study. Testing for the case of 2H stacking indicates that TDDFT-MD calculations using the LDA and PBE+vdW functionals yield quite similar results for the hole transfer dynamics across the heterostructure. We use optimized lattice constants 3.16 Å and all the atoms are fully relaxed until the residual forces are <0.025 eV Å−1. In the dynamics calculations, we use NVE ensemble, a time step of 24.19 attoseconds, and the Ehrenfest approximation for ionic motion. Initial ion positions and velocities are obtained from ground-state MD simulations at the target ionic temperature.

supercell containing 162 atoms with Γ-point for the Brillouin zone integration is used. Note that the K-point of primitive cell is folded to the Γ point in this supercell. In contrast to the well-known underbinding character in the PBE functional, the LDA reproduces the experimental structural parameters quite well for the vdW systems, as shown in Table 2. Although vdW forces are not explicitly included in the LDA formalism, LDA is known to yield a good description of forces between layers in TMDs as indicated by the quantitative agreement of the layer-to-layer vibration modes in these systems, as compared with experimental Raman data31,40,41,42,43. Furthermore, LDA predicts the preference of the 2H stacking, similar to the vdW density functionals (which are built on top of semi-classical GGA functionals such as PBE)29. We consider 3R, AB′ and 2H stacking patterns for the MoS2/WS2 heterostructures28,29, but we focus our discussion on the 2H stacking patterns in this study. Testing for the case of 2H stacking indicates that TDDFT-MD calculations using the LDA and PBE+vdW functionals yield quite similar results for the hole transfer dynamics across the heterostructure. We use optimized lattice constants 3.16 Å and all the atoms are fully relaxed until the residual forces are <0.025 eV Å−1. In the dynamics calculations, we use NVE ensemble, a time step of 24.19 attoseconds, and the Ehrenfest approximation for ionic motion. Initial ion positions and velocities are obtained from ground-state MD simulations at the target ionic temperature.

Phonon decomposition

The eigenvectors,  , and eigenvalues, ωn, of the normal modes of the system were determined by diagonalizing the dynamical matrix as implemented in SIESTA. Cartesian coordinates of the atomic trajectories during the TDDFT-MD simulation are recast in terms of the normal mode coordinates, qn, by projecting the ionic displacements from equilibrium onto the eigenvectors of the dynamical matrix. In this way, the energy of each normal mode is determined throughout the simulation, according to

, and eigenvalues, ωn, of the normal modes of the system were determined by diagonalizing the dynamical matrix as implemented in SIESTA. Cartesian coordinates of the atomic trajectories during the TDDFT-MD simulation are recast in terms of the normal mode coordinates, qn, by projecting the ionic displacements from equilibrium onto the eigenvectors of the dynamical matrix. In this way, the energy of each normal mode is determined throughout the simulation, according to  .

.

Model calculation

The model calculations are performed by numerically integrating the Liouville equation,  , to obtain the density matrix as a function of time. To incorporate the dissipation to the phonon modes observed in the TDDFT-MD calculations at elevated temperatures in the model, the interaction of the system with a heat bath is considered in an average way. In every step in the time evolution of ρ, we enforce a Kraus transformation44 where

, to obtain the density matrix as a function of time. To incorporate the dissipation to the phonon modes observed in the TDDFT-MD calculations at elevated temperatures in the model, the interaction of the system with a heat bath is considered in an average way. In every step in the time evolution of ρ, we enforce a Kraus transformation44 where

with P being the probability that the event of phonon emission with the hole transitioning to a lower energy state (that is, |MoS2〉|n〉bath→|WS2〉n+1〉bath) takes place in the time δt. Note here that the bath is Markovian and only dissipates energy, we do not consider events which raise the energy of the hole. From Fermi’s golden rule, the probability of such a transition is directly proportional to the square of the amplitude of the receiving mode, allowing for the relation of the transition probabilities for different temperatures. Here, however, it is important to note that while the TDDFT-MD calculation is not on the Born–Oppenheimer surface, the ions are still treated as classical objects, and hence the energies of the normal modes in the TDDFT-MD calculations follow a classical equipartition theorem with E=kT, instead of Bose–Einstein statistics. Hence, for the case of classical ions, assuming a single phonon decay channel associated with a frequency ω, we can simultaneously fit both the dynamics at 77 K and 300 K with a single coupling parameter, g, where the temperature-dependent transition probability becomes

While the amplitude distributions of the normal modes associated with the fully quantum mechanical system are not well represented in the TDDFT-MD, the underlying coupling is well described by the Ehrenfest approximation and hence it is expected that the fitted coupling parameter, g, associated with the decay process is still valid. Hence, we can improve the TDDFT-MD simulations to more adequately represent the fully quantum mechanical case by replacing the amplitudes in equation (4) by those correctly determined from the Bose-Einstein distribution yielding,

By correcting for this shortcoming, we can go beyond the TDDFT-MD to more accurately calculate charge transfer dynamics at low T, as shown in Fig. 5c. In this case the temperature dependence is much less pronounced and we see nearly complete charge transfer in a 100 fs timescale even as we approach T=0 K. This relative insensitivity to temperature is a result of the decay process dominated by high-frequency phonons, which even at room temperature have only very modest phonon occupation (for instance at 300 K, n∼0.16). By directly comparing Fig. 5b,c, we see that only as we approach room temperature do the classical and quantum pictures of ionic motion yield correspondence.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Wang, H. et al. The role of collective motion in the ultrafast charge transfer in van der Waals heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 7:11504 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11504 (2016).

References

Blankenship, R. E. Molecular Mechanisms of Photosynthesis Wiley (2002).

Kudo, A. & Miseki, Y. Heterogeneous photocatalyst materials for water splitting. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 253–278 (2009).

Alferov, Z. I. Nobel Lecture: the double heterostructure concept and its applications in physics, electronics, and technology. Rev. Mod. Phys. 73, 767–782 (2001).

Heeger, A. J. 25th anniversary article: bulk heterojunction solar cells: understanding the mechanism of operation. Adv. Mater. 26, 10–27 (2014).

Mimura, T. The early history of the high electron mobility transistor (HEMT). IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 50, 780–782 (2002).

Deibel, C., Strobel, T. & Dyakonov, V. Role of the charge transfer state in organic donor–acceptor solar cells. Adv. Mater. 22, 4097–4111 (2010).

Shaheen, S. E. et al. Energy and charge transfer in organic light-emitting diodes: a soluble quinacridone study. J. Appl. Phys. 85, 7939–7945 (1999).

Geim, A. K. & Grigorieva, I. V. Van der Waals heterostructures. Nature 499, 419–425 (2013).

Kosmider, K. & Fernandez-Rossier, J. Electronic properties of the MoS2-WS2 heterojunction. Phys. Rev. B 87, 75451 (2013).

Wang, H. et al. Two-dimensional heterostructures: fabrication, characterization, and application. Nanoscale 6, 12250–12272 (2014).

Lotsch, B. V. Vertical 2D heterostructures. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 45, 85–109 (2015).

Pop, E., Varshney, V. & Roy, A. K. Thermal properties of graphene: fundamentals and applications. MRS Bull. 37, 1273–1281 (2012).

Katsnelson, M. I., Novoselov, K. S. & Geim, A. K. Chiral tunnelling and the Klein paradox in graphene. Nat. Phys. 2, 620–625 (2006).

Rycerz, A., Tworzydlo, J. & Beenakker, C. W. J. Valley filter and valley valve in graphene. Nat. Phys. 3, 172–175 (2007).

Sie, E. J. et al. Valley-selective optical Stark effect in monolayer WS2 . Nat. Mater. 14, 290–294 (2015).

Cao, T. et al. Valley-selective circular dichroism of monolayer molybdenum disulphide. Nat. Commun. 3, 887 (2012).

Bernardi, M., Palummo, M. & Grossman, J. C. Extraordinary sunlight absorption and one nanometer thick photovoltaics using two-dimensional monolayer materials. Nano Lett. 13, 3664–3670 (2013).

Splendiani, A. et al. Emerging photoluminescence in monolayer MoS2 . Nano Lett. 10, 1271–1275 (2010).

Gutierrez, H. R. et al. Extraordinary room-temperature photoluminescence in triangular WS2 monolayers. Nano Lett. 13, 3447–3454 (2013).

Hong, X. et al. Ultrafast charge transfer in atomically thin MoS2/WS2 heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 682–686 (2014).

Gong, Y. et al. Vertical and in-plane heterostructures from WS2/MoS2 monolayers. Nat. Mater. 13, 1135–1142 (2014).

Ceballos, F., Bellus, M. Z., Chiu, H.-Y. & Zhao, H. Ultrafast charge separation and indirect exciton formation in a MoS2–MoSe2 van der Waals heterostructure. ACS Nano 8, 12717–12724 (2014).

Lee, C.-H. et al. Atomically thin p-n junctions with van der Waals heterointerfaces. Nat. Nanotech. 9, 676–681 (2014).

Yu, Y. et al. Equally efficient interlayer exciton relaxation and improved absorption in epitaxial and nonepitaxial MoS2/WS2 heterostructures. Nano Lett. 15, 486–491 (2015).

Marcus, R. A. Electron transfer reactions in chemistry: Theory and experiment. Rev. Mod. Phys. 65, 599–610 (1993).

van Hal, P. A., Meskers, S. C. J. & Janssen, R. A. J. Photoinduced energy and electron transfer in oligo(p-phenylene vinylene)-fullerene dyads. Appl. Phys. A 79, 41–46 (2004).

Wasielewski, M. R. Photoinduced electron transfer in supramolecular systems for artificial photosynthesis. Chem. Rev. 92, 435–461 (1992).

van der Zande, A. M. et al. Tailoring the electronic structure in bilayer molybdenum disulfide via interlayer twist. Nano Lett. 14, 3869–3875 (2014).

He, J., Hummer, K. & Franchini, C. Stacking effects on the electronic and optical properties of bilayer transition metal dichalcogenides MoS2, MoSe2, WS2, and WSe2 . Phys. Rev. B 89, 75409 (2014).

Komsa, H.-P. & Krasheninnikov, A. V. Electronic structures and optical properties of realistic transition metal dichalcogenide heterostructures from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 88, 85318 (2013).

Berkdemir, A. et al. Identification of individual and few layers of WS2 using Raman spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 3, 1755 (2013).

Lee, C. et al. Anomalous lattice vibrations of single- and few-layer MoS2 . ACS Nano 4, 2695–2700 (2010).

Falke, S. M. et al. Coherent ultrafast charge transfer in an organic photovoltaic blend. Science 344, 1001–1005 (2014).

Andrea Rozzi, C. et al. Quantum coherence controls the charge separation in a prototypical artificial light-harvesting system. Nat. Commun. 4, 1602 (2013).

Runge, E. & Gross, E. K. U. Density-functional theory for time-dependent systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 52, 997–1000 (1984).

Soler, J. M. et al. The SIESTA method for ab initio order-N materials simulation. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 14, 2745–2779 (2002).

Meng, S. & Kaxiras, E. Real-time, local basis-set implementation of time-dependent density functional theory for excited state dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 129, 054110 (2008).

Sugino, O. & Miyamoto, Y. Density-functional approach to electron dynamics: Stable simulation under a self-consistent field. Phys. Rev. B 59, 2579–2586 (1999).

Ceperley, D. M. & Alder, B. J. Ground State of the Electron Gas by a Stochastic Method. Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 566–569 (1980).

Zhao, Y. et al. Interlayer breathing and shear modes in few-trilayer MoS2 and WSe2. Nano Lett. 13, 1007–1015 (2013).

Puretzky, A. A. et al. Twisted MoSe2 bilayers with variable local stacking and interlayer coupling revealed by low-frequency raman spectroscopy. ACS Nano 10, 2736–2744 (2016).

Huang, S. et al. Low-frequency interlayer raman modes to probe interface of twisted bilayer MoS2 . Nano Lett. 16, 1435–1444 (2016).

Puretzky, A. A. et al. Low-frequency raman fingerprints of two-dimensional metal dichalcogenide layer stacking configurations. ACS Nano 9, 6333–6342 (2015).

Kraus, K., Böhm, A., Dollard, J. D. & Wootters, W. H. States, Effects, and Operations: Fundamental Notions of Quantum Theory: Lectures in Mathematical Physics at the University of Texas at Austin Springer-Verlag (1983).

Liang, L. & Meunier, V. First-principles Raman spectra of MoS2, WS2 and their heterostructures. Nanoscale 6, 5394–5401 (2014).

Wildervanck, J. C. & Jellinek, F. Preparation and Crystallinity of Molybdenum and Tungsten Sulfides. Zeitschrift für Anorganische und Allgemeine Chemie 328, 309–318 (1964).

Acknowledgements

We thank D. Han, E. Cruz-Silva and M. Lucking for helps on TDDFT-MD and valuable suggestions. We also thank Ashok Kumar for sharing with us the pseudopotentials and Liang Chen for helping with understanding related experiments. H.W., D.W., Y.S. and S.Z. were supported by the US Department of Energy (DOE) under Grant No. DE-SC0002623, J.B. was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2015R1C1A1A02037024) and KBSI grant C36117, L.L. was supported by Eugene P. Wigner Fellowship at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences (a DOE Office of Science User Facility), and V.M. acknowledges support from the Office of Naval Research and New York State under NYSTAR program C080117. We also acknowledge the supports by the supercomputer time provided by NERSC under the Grant No. DE-AC02-05CH11231 and the Center of Computational Innovations (CCI) at RPI.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The TDDFT-MD calculations were performed by H.W. under the guidance of J.B. Electronic structure calculations were performed by Y.S. and L.L. The phonon and Raman analysis was carried out by L.L. and D.W. The model was developed and investigated by H.W. and D.W. The paper was written by H.W., J.B. and D.W. with contributions from all authors. V.M. and S.Z. supervised the research.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, H., Bang, J., Sun, Y. et al. The role of collective motion in the ultrafast charge transfer in van der Waals heterostructures. Nat Commun 7, 11504 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11504

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11504

This article is cited by

-

Carbon defect qubit in two-dimensional WS2

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Interlayer exciton formation, relaxation, and transport in TMD van der Waals heterostructures

Light: Science & Applications (2021)

-

Lightwave-driven scanning tunnelling spectroscopy of atomically precise graphene nanoribbons

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Nonadiabatic dynamics of cobalt tricarbonyl nitrosyl for ligand dissociation induced by electronic excitation

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Interlayer charge transport controlled by exciton–trion coherent coupling

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.