Abstract

Background:

Childhood obesity has been becoming a worldwide public health problem. We conducted a community-based physical activity (PA) intervention program aiming at childhood obesity prevention in general student population in Nanjing of China, the host city of the 2nd World Summer Youth Olympic Games (YOG-Obesity study).

Methods:

This was a cluster randomized controlled intervention study. Participants were the 4th (mean age±s.e.: 9.0±0.01) and 7th (mean age±s.e.: 12.0±0.01) grade students (mean age±s.e.: 10.5±0.02) from 48 schools and randomly allocated (1:1) to intervention or control groups at school level. Routine health education was provided to all schools, whereas the intervention schools additionally received an 1-year tailored multi-component PA intervention program, including classroom curricula, school environment support, family involvement and fun programs/events. The primary outcome measures were changes in body mass index, obesity occurrence and PA.

Results:

Overall, 9858 (97.7%) of the 10091 enrolled students completed the follow-up survey. Compared with the baseline, PA level increased by 33.13 min per week (s.e. 10.86) in the intervention group but decreased by 1.76 min per week (s.e. 11.53) in the control group (P=0.028). After adjustment for potential confounders, compared with the control group, the intervention group were more likely to have increased time of PA (adj. Odds ratio=1.15, 95% confidence interval=1.06–1.25), but had a smaller increase in mean body mass index (BMI) (0.22 (s.e. 0.02) vs 0.46 (0.02), P=0.01) and BMI z-score (0.07 (0.01) vs 0.16 (0.01), P=0.01), and were less likely to be obese (adj. Odds ratio=0.7, 95% confidence interval=0.6, 0.9) at study end. The intervention group had fewer new events of obesity/overweight but a larger proportion of formerly overweight/obese students having normal weight by study end.

Conclusions:

This large community-based PA intervention was feasible and effective in promoting PA and preventing obesity among the general student population in a large city in China. Experiences from this study are the lessons for China to control the childhood obesity epidemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Childhood obesity, largely resulting from unhealthy diets and physical inactivity, has become a major public health threat in China and worldwide.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Recent studies showed that obesity not only has adverse consequences on physical and mental health for children,12, 13 but also increases the risks of developing cardio-metabolic disorders (for example, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, insulin resistance, diabetes mellitus and arteriosclerosis) when children enter adulthood.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 Hence, preventing and treating obesity at an early age benefits health during the entire life course.

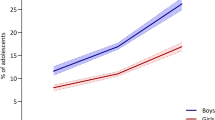

As the world’s fastest growing economy over the past two decades, China also has seen dramatic growth of childhood overweight/obesity. In urban China, 30% of boys and 16% of girls are overweight or obese, based on recent nationally representative data.20, 21, 22 Therefore, there is an urgent need to curb and reduce childhood obesity prevalence by designing and implementing evidence-based sustainable healthy eating and/or physical activity (PA) programs among the general child population.

Multi-component lifestyle intervention strategies to prevent childhood obesity have been shown to be effective for school-based childhood obesity prevention, but often the studies were at a small scale.9, 10, 11, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 Thus, their findings are limited as useful guidelines for public health professionals and policy makers. We developed and implemented a school-based lifestyle intervention trial among local school students (CLICK-Obesity study, n=1182) in 2010 and found the program to be effective and feasible as a scientific research study.28, 29 However, there is a large gap between scientific research-based findings and policy-oriented practice regarding childhood obesity prevention through lifestyle intervention among school students.

To fill this gap, we conducted a large-scale (n>10 000) PA promotion program during 2013–2014, namely the HLP (Health Legacy Project) of the 2nd Summer Youth Olympic Games (YOG), which was initiated by the International Olympic Committee (IOC), in Nanjing of China, the host city of the 2nd YOG (YOG-Obesity study). This Legacy Project was a controlled intervention of a policy-oriented PA intervention program, in that the local education administration asked intervention-arm schools to integrate all of the intervention components into the routine health education program under the existing educational, social and cultural context. The ultimate goal was to examine to what extent research findings could be translated into policy-oriented practice. We assessed intervention effectiveness based on changes in students' PA level and body weight status.

Methods

Study design and participants

The HLP of the 2014 YOG was a school-based multi-component cluster randomized controlled PA promotion program implemented among 4th and 7th grade students in eight urban districts of Nanjing, China. The intervention lasted for 1 academic school year (from September 2013 to June 2014).

A multi-stage sampling method was employed to select participants. First, sample size was determined based on several assumptions: the expected difference (0.1 kg m−2) in body mass index (BMI) change between intervention and control groups after intervention, the standard deviation of BMI (3.0 between different schools), α=0.05 (one-sided) and β=0.1, design effect=2.49 based on ICC in our previous study;28, 29 thus, the total number of participants needed was estimated to be 5000 primary and 5000 junior high school students. Second, based on the average number of students per class by grade enrolled in 2011, we calculated the number of participating classes for primary and junior high schools, respectively. Third, assuming that an entire grade of students would be selected from each school and considering the average number of classes per grade in primary and junior high schools, we estimated that four primary and two junior high schools should be randomly selected from each of the eight urban districts. Thus, 32 primary and 16 junior high schools were selected in total, and all of the 4th and 7th graders in the selected participating schools were eligible study subjects, resulting in 10 447 students in the baseline survey.

Randomization regarding allocation of intervention and control was performed by research team at the school level based on the 1:1 matching proportion within each urban district, using random numbers generated by software of Epical 2000. There were two vs two primary schools and one vs one junior high schools randomly assigned to intervention vs control group in each selected urban district. Totally, there were 16 vs 16 primary schools and 8 vs 8 junior high schools within intervention vs control group in this study.

This project was approved by the Academic and Ethical Committee of Nanjing Municipal Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Nanjing CDC) and its pilot study was registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR-ERC-11001819). Signed informed consents for this study were obtained from parents/guardians and schools prior to the baseline survey. All personally identifiable information was removed prior to data analysis.

Intervention components and implementation

All of the intervention components were initially developed and the effectiveness was examined in our 2010–2011 CLICK-Obesity study among 1182 primary school students,28, 29 and they were further refined in the present study by addressing the following main components (Figure 1). Our interventions were described in details with attempts to guarantee the replication by other researchers.30, 31

(a) Classroom curricula

These curricula consisted of knowledge of obesity and its hazards to health, the benefits of sufficient PA for body weight control, and skills to maintain sufficient PA, reduce screen time and take physically active transportation in daily lives. All the curricula (45 min for each classroom curriculum) were developed by our research team but delivered monthly to students by classroom teachers who were specially trained for teaching health knowledge to students. As an approach of quality control, one or two program members attended each class to view the curriculum presentation lesson.

In China, there is a blackboard on the rear wall within each classroom, which is used to present students' writing, painting assignment based on selected themes. In this study, we made use of the blackboard to enhance students’ knowledge and skills learned from the classroom teaching, by asking them to develop a blackboard presentation on a monthly basis focusing on the contents that they acquired from the classroom teaching accordingly.

(b) School environment support

School environment can be of help for students to make desirable health-related behavioral modification and maintain a healthy behavior/lifestyle. The intervention approach of school environment support included three sub-components.1 Posters and slogans encouraging students to engage in sufficient PA were posted on billboards inside the classroom, gymnasium, playground and cafeteria and refreshed bimonthly according to the scheduled intervention curriculum themes within each intervention school. Selected example titles of the posters/slogans included: ‘Being obese at childhood may lead to being obese at adulthood too’, ‘To be physically active is a good and wise way to reject obesity’ and ‘The less screen time, the better body health'.2 Easily-accessed instruments for body weight and height measurement and BMI calculation were provided within each intervention classroom in the first month of intervention. Students could calculate their BMI by measuring their body weight and height at any class break period or any time they were convenient. And3 news leaflets regarding program progress were developed and sent to participating schools, students and families quarterly. In this way, each intervention school, student and his/her parents were able to know what intervention components had been delivered and what knowledge and skills the student learned.

(c) Family involvement

Parents live together with their children and thus can be able to exert critical influences on their children's behavioral patterns and lifestyles during daily lives. Family involvement sub-component was designed to introduce our intervention to parents and to assist them to create a supportive family environment for helping their children change unhealthy behaviors and promote PA. Families (parents) were involved in this study via three ways. First, one health class was prepared for parents in each semester, with topics covering knowledge of childhood obesity, the health consequences of physical inactivity, and skills to help children maintain sufficient PA in their daily lives. Unlike the classroom curricula for students which were presented by class teachers, the curriculum designed for parents were developed and delivered by our team members, whereas class teachers helped organize it. Second, parents were assigned homework and asked to complete it with their children (for example, measuring body weight and height, calculating each other’s BMI) in the first semester. Third, with assistance from parents, three special 1-week activities were developed for all intervention students in the second semester, including:1 Physical housework week: Students engaged in PA through helping parents do physical housework at home, such as house cleaning, raw food preparation and dishwashing, for 1 week;2 Walk-to-school week: Intervention children were encouraged to walk or ride bicycle to/from school for 1 week; and3 No-TV week: during this week, students were asked not to view TV in an attempt to reduce their sedentary time. A one-page 7-day diary, developed to track these three themed 1-week activities, were recorded by students themselves but audited by their parents during the week.

(d) Fun programs/events

In China, language (Chinese and English) and painting are compulsory courses for primary and junior high school students. Under this context, we designed two fun events for intervention students with consideration of the regular curricula.1 A composition writing was arranged to the intervention students by class teachers. Each student within the intervention class was required to complete a composition writing with a focus on obesity and its hazards to health, PA and its impact on body weight control in the first semester.2 A painting class with the theme of PA events in daily life was organized in the second semester. With such painting work, students were encouraged to tell the PA-related stories happened to themselves or around them in daily lives.3 Furthermore, a live team competition of knowledge and skills regarding obesity and PA was held for all intervention students during the second semester. One team (three students) was selected from each district, resulting in eight teams to participate in the final team competition. Three students were chosen to be the team members based on their performances of preliminary contest within each district. Therefore, there were 24 students taking part in the final contest.

As incentives, excellent works and performance were selected by an external expert panel. All the composition and painting works were reviewed by the expert panel and six works from each intervention school were selected and granted excellent composition or painting, separately. The winners were granted specific certificates. Regarding the team live show, three teams were elected as excellent performance, whereas all 24 participants were named as culture representatives of YOG.

All these intervention components were developed and integrated into the regular academic schedule of each intervention school after taking full consideration of Chinese cultural and social convention, the current primary education and examination system, and particularly, the familial tradition. In China, parents usually expect their children to spend a relatively large amount of time in academic studies for achieving highly competitive exam scores, whereas schools primarily define the schools' reputation by their students’ academic performance. With attempts to minimize interference with school's regular curricula and to obtain strong support from both parents and school administration, these cultural and social contexts must be considered when designing and implementing school-based lifestyle and behavioral intervention programs in China.

Local government was also involved in the intervention and played a critical role. The Nanjing Municipal Education Department and Health Department jointly issued an official document asking the intervention schools to integrate all of the intervention components into their regular curriculum schedules and deliver them to students. Meanwhile, Nanjing CDC provided technical support for the intervention programs in intervention schools. This PA intervention program was based on such policy support, which was considered to be critically important to guarantee us the ability to translate our previous research into the present large-scale study. Both control and intervention students received their routine health education programs regulated by educational authority, whereas participants within intervention schools additionally received those specially developed interventions components described above.

Data collection and measurements

Students’ demographic characteristics, PA, obesity- and healthy lifestyle-related knowledge and dietary behaviors were assessed using validated questionnaires, whereas background information such as parental education, family size and structure was collected from parents/guardians using a separate self-administered short questionnaire. A validated item-specific PA questionnaire, CPAIQ (Children Physical Activity Item Questionnaire), was used to collect information on students' PA over the past 7 days, including the name of each PA, frequency and duration.32 Consumption of red meat, vegetables, fast-food and soft-drinks in the past 7 days were assessed using items selected from a validated food frequency questionnaire.33 The baseline and post-intervention questionnaires were separately administered by onsite research team members in each classroom with the assistance of the classroom teacher.

Based on a standardized protocol, students' body weight and height were measured at both baseline and post-intervention to the ~0.1 kg and to the ~0.01 m, respectively, by trained research staff. Measures were taken twice and the mean of the two readings was used in the analysis.

Key study variables

Outcome variables

The major outcome variables used to evaluate the effectiveness of the study intervention were changes in body weight outcomes and PA levels before and after intervention.

(1) Weight outcomes

-

a

BMI: weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

-

b

BMI z-score: the deviation of the value for an individual from the mean value divided by the standard deviation based on the recommendation for Chinese children.34

-

c

Weight status (overweight and obesity): assessed according to the specifically recommended age- and gender-specific references for Chinese children.35

(2) PA

In the overall participating population, PA level was evaluated based on the total time spent in leisure-time moderate–vigorous intensity PA (MVPA) during the past 7 days, which was calculated as the time of moderate-intensity PA (metabolic equivalent 3–6) plus double the time of vigorous intensity PA (⩾ 6). Considering that population level PA increase (the mean value) might be caused by either many students with PA increased or a small number of students with their PA time increased by a large amount of time, we developed two sub-measures of PA to assess the effectiveness of the study intervention: (a) The mean value of the 7 days' MVPA time; and (b) The percentage of students with increased MVPA time after intervention.

Exposure variable

Intervention treatment was the main exposure variable in the analysis. Intervention and control schools were indicated by a dummy variable (1, intervention; 0, control).

Covariates

Demographic information, including students' age, gender, red meat consumption (tertiled weekly frequency) at baseline and their parents' education level (⩽ 9 yrs, 10–12 yrs and >12 yrs) were included as covariates in analysis.

Data analysis

Characteristics of study participants were compared by treatment (control vs intervention group). Comparisons between students who completed the baseline survey but were lost to follow-up and those who completed both baseline and follow-up surveys were conducted using Student’s t-tests (for continuous variables) and χ2-tests (for categorical variables).

Intervention effects were assessed using mixed effect models in a difference-in-difference design with adjustment for school-level clustering effects, participants' age, gender, baseline body weight, red meat consumption at baseline (adjusted for assessing BMI and its z-score) and parents' educational level. According to the sampling approach, the clustering effects might derive from schools. Thus, the potential school level clustering effects were explicitly considered in the mixed-effects models used in our analysis.

The weight outcomes in the regression analyses included: (a) difference in the changes of BMI; (b) difference in the changes of BMI z-score; and (c) difference in the changes of overweight/obesity prevalence. Regarding PA, the outcomes included: (a) difference in the mean value of 7 days' moderate PA time between pre- and post-intervention; and (b) difference in the percentage of students with increased moderate PA time before and after intervention.

Outcomes from mixed-effects regression models were reported as effect estimates and 95% confidential intervals (95% CIs). Stratified analyses were conducted to estimate the potential differences in intervention effects based on gender and subjects’ baseline weight status. All analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics

Of those 10 447 eligible participants, 10 091 students were successfully recruited (response rate=96.6%) at baseline, and 9858 (97.7%) of them completed the follow-up survey immediately after the intervention. At baseline, the mean (s.e.) age was 10.5 (0.02) of overall participants, whereas 9.0 (0.01) and 12.0 (0.01) of graders four and seven in this study, respectively. Furthermore, participants from intervention and control schools were comparable in age (mean (s.e.) 10.5 (0.02) vs 10.5 (0.02) years, P=0.58), sex (53.2 vs 52.8% boys, P=0.70) and BMI (mean (s.e.) 19.3 (0.05) vs 19.3 (0.05) kg m−2, P=0.45).

The main reasons for loss to follow-up (n=233) were sickness or other scheduled events on the survey day. A participant flow chart of the study is displayed in Figure 2. Also, there was no significant difference in the baseline mean BMI between those followed-up and not followed-up (mean (s.d.) 19.3 (3.7) vs 19.3 (3.8) kg m−2, P=0.99). Table 1 presents the baseline socio-demographic and anthropometric characteristics of the participants.

Intervention effects on PA

PA levels of both intervention and control schools were comparable at baseline (P=0.33, Table 2). At study end, students in the intervention schools achieved a 33.13 min per week increase in MVPA, whereas their counterparts in control schools had a 1.76 min per week decrease in MPA (β=49.1, 95% CI=4.1, 94.0). However, the effect of the intervention on PA time became statistically non-significant after adjusting for potential confounders (β=37.6, 95% CI=−43.9, 119.1).

The percentage of students in the intervention and control groups with increased PA time at study end also were analyzed to assess the effects of the intervention on PA. 53.9% (2841/5275) of students in intervention schools and 50.6% (2321/4583) in control schools reported increased weekly MVPA time at study end relative to baseline. Our mixed-effects model estimates indicated that, after adjustment for potential confounders, students in intervention schools were more likely to have improved their MVPA time (adj. OR=1.15, 95% CI=1.06, 1.26) at study end compared with their counterparts in control schools (Table 2).

Intervention effects on BMI and weight status

Table 3 presents the study effects based on changes in BMI, BMI z-score, and percentage of obesity/overweight for intervention vs control groups. During the course of the intervention year, although BMI and BMI z-scores increased for students in both intervention and control schools, the increase in either BMI (intervention vs control=mean (s.e.) 0.22 (0.02) vs 0.46 (0.02), adj.β=−0.3, 95% CI=−0.5, −0.1) or BMI z-score (intervention vs control=mean (s.e.) 0.07 (0.01) vs 0.16 (0.01), adj.β=−0.1, 95% CI=−0.2, −0.03) was significantly smaller for intervention students than for controls.

The changes (follow-up–baseline) in the prevalence of either obesity (intervention vs control=0.6 vs 2.3%) or obesity/overweight (intervention vs control=0.9 vs 2.9%) increased in both intervention and control students at study end, and these increases were smaller in intervention schools. Even after adjusting for potential confounds, the mixed-effects model estimates suggested students in the intervention schools were less likely to become obese (adj. OR=0.7, 95% CI=0.6, 0.9) or overweight or obese (adj. OR=0.8, 95% CI=0.7, 1.0).

Table 4 shows the changes (follow-up–baseline) in BMI z-scores between intervention and control groups according to baseline weight status. For the non-overweight students at baseline, subjects in intervention schools had significantly smaller increases in BMI z-scores compared with their counterparts in control schools, irrespective of whether they remained non-overweight (intervention vs control=mean (s.e.) 0.07 (0.01) vs 0.14 (0.01), adj.β=−0.08, 95% CI=−0.15, −0.01) or became overweight/obese (intervention vs control=mean (s.e.) 0.58 (0.03) vs 0.84 (0.08), adj.β=−0.26, 95% CI=−0.50, −0.01) at study end. Moreover, for those overweight/obese children at baseline, a significantly smaller increase in BMI z-scores was observed for students remaining overweight/obese in intervention schools relative to their counterparts in control schools (intervention vs control=mean (s.e.) 0.08 (0.01) vs 0.13 (0.01), adj. β=−0.08, 95% CI= −0.15, −0.01).

There was a significant difference between intervention and control schools in the proportion of students who changed their body weight status either from baseline normal weight to end-point excess body weight (intervention vs control=7.8% (269/3429) vs 9.2% (277/3017), P=0.054) or from baseline excess body weight to end-point normal weight (3412 intervention vs control=12.0% (221/1845) vs 9.1% (143/1567), P=0.008).

Discussion

This study examined the effectiveness of the Health Legacy Project of the 2nd World Summer Youth Olympic Games. The HLP is the first large-scale school-based multi-component intervention study conducted in China. The intervention program was integrated into the routine and normal academic educational system. Multilevel stakeholders including parents, teachers, and local policy makers were involved in the study. Our findings suggest the HLP intervention significantly improved PA and reduced the risk of overweight/obesity for students in intervention schools compared to their counterparts in control schools. Our previous research findings and experience were successfully translated into this large-scale community-based PA intervention program among a general student population.

Our intervention substantially increased the likelihood of students engaging in MVPA. Compared with the control group, students in the intervention group were 15% more likely to participate in MVPA. PA can not only improve biomarkers of chronic disease risk,36 but also benefit children’s physical and mental development.24, 37, 38 Our results suggest that, compared with their counterparts in control schools, students in intervention schools were more likely to have their PA time increased, although the mean PA time increase was not significantly higher, which might be owing to the relatively short period of intervention.

Our results show that participants in the intervention group significantly reduced their BMI compared with the control group. This finding is expected and confirms the conclusion from a comprehensive review regarding the effectiveness of childhood obesity intervention programs that PA promotion is one of the potential major pathways to curbing childhood obesity.24 In addition to BMI, our findings also suggest that our intervention can help reduce the risk of childhood obesity. Intervention participants had ~30% lower risk of developing into new obesity cases compared to control participants.

Stratified analysis was also performed to investigate the effects of the intervention by gender and baseline weight status. Our estimates did not suggest significant differences in intervention effects across these factors. These results indicate the potential feasibility, applicability, and effectiveness of our intervention to broader general child populations, regardless of gender and weight status.

From a public health perspective, in terms of preventing childhood obesity among the general student population, it is particularly important to apply feasible and effective lifestyle intervention strategies obtained from small sample size trials to the large-scale general child population as regular and routine school-based obesity prevention practices.39, 40, 41 The present study was specifically designed to meet this need through enhancing long-term participation in PA for primary and junior high school students.

It is not easy to make comparison between our intervention program and other similar studies because of different study designs, intervention components and periods, settings, outcome assessment, social and educational contexts. According to a recent systematic review on childhood obesity intervention programs led by one of our team member, among the 124 school-based obesity intervention studies included in this review, 21 were RCTs and only four of the 21 RCTs were similar to our study.24 However the results were still mixed amongst these four studies, with one showing no significant effectiveness42 while the results of other three studies favoring the intervention.43, 44, 45 Furthermore, it is interesting to make comparison between our study and those from Asian countries. We found that only one similar study was from India,46 in which1 a small intervention program was implemented with only two schools involved (N=201);2 its participants were students aged 15–17 years;3 intervention period lasted 8 months;4 intervention components included healthy eating and sufficient PA; and5 no positive changes were observed in terms of BMI after intervention was completed. However, it is not feasible to compare the results of intervention between our program and the Indian study because the authors of the Indian study did not provide detailed information on how their intervention was implemented.

This intervention study has several key strengths. First, it represents the first large-scale research translated project. The findings suggest the potential feasibility and success of implementing this intervention in larger populations in China. Second, the sample size was large, thus allowing adequate study power to detect small intervention effects. Third, policy makers were involved in the intervention and the success of this intervention project suggests the critical role that government can and should play in the battle with childhood obesity. Finally, regarding the feasibility of this intervention, intervention components were delivered to participants without interference with participating schools' curriculum and academic programs. Neither complaints nor adverse events were reported by any students or school personnel.

The study also has some limitations. First, PA was self-reported. However, the CPAIQ was specifically validated for Chinese adolescents. Second, participating schools were limited to urban areas of Nanjing City. Therefore, the findings may not be generalizable to students living in rural areas. Third, the impact of family support on the success of our intervention could not be examined due to challenges in collecting data from parents. Fourth, possible contamination from the potential beneficial effects of hosting the 2nd Youth Olympic Games is a concern, but such contamination should have a similar impact on the desirable outcomes between the intervention and control group and thus was regarded as non-differential, which in turn, yielded an attenuation of the observed effect. Finally, all the effects reported in this paper were based on a 1-year PA intervention, which did not imply any explanation on the intervention effects for a longer term. However, we are confident to foresee its success for a longer period if the community-based intervention was extended for a longer period. The long-term effect of this community-based PA intervention warrants further research.

In conclusion, this large community-based PA intervention was feasible and effective in promoting PA and preventing obesity among the general student population in a large city in China. Such programs were policy-oriented with multi-components involving classroom curricula, school environment support, family involvement and fun programs/events. Experiences from this study are the lessons for China and other countries to design effective intervention strategies for controlling the rapid growing childhood obesity epidemic.

References

Wang Y, Monteiro C, Popkin BM . Trends of obesity and underweight in older children and adolescents in the United States, Brazil, China, and Russia. Am J Clin Nutr 2002; 75: 971–977.

Lobstein T, Baur L, Uauy R . Obesity in children and young people: a crisis in public health. Obesity Rev 2004; 5: 4–85.

Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014; 384: 766–781.

Wang Y, Lobstein T . Worldwide trends in childhood overweight and obesity. Int J Pediatr Obes 2006; 1: 11–25.

Han JC, Lawlor DA, Kimm SY . Childhood obesity. Lancet 2010; 375: 1737–1748.

He Q, Ding Z, Fong D, Karlberg J . Risk factors of obesity in preschool children in China: a population-based case-control study. Int J Obesity 2000; 24: 1528–1536.

Shan XY, Xi B, Cheng H, Hou DQ, Wang Y, Mi J . Prevalence and behavioral risk factors of overweight and obesity among children aged 2–18 in Beijing, China. Int J Pediatr Obes 2010; 5: 383–389.

Wang Y, Ge K, Popkin BM . Tracking of body mass index from childhood to adolescence: a 6-y follow-up study in China. Am J Clin Nutr 2000; 72: 1018–1024.

Pigeot I, Barba G, Chadjigeorgiou C, de Henauw S, Kourides Y, Lissner L et al. Prevalence and determinants of childhood overweight and obesity in European countries: pooled analysis of the existing surveys within the IDEFICS Consortium. Int J Obes 2009; 33: 1103–1110.

Flynn MA, McNeil DA, Maloff B, Mutasingwa D, Wu M, Ford C et al. Reducing obesity and related chronic disease risk in children and youth: a synthesis of evidence with 'best practice' recommendations. Obes Rev 2006; 7: 7–66.

World Health Organization. Reasons for children and adolescents to become obese 2013 [cited 2016 May 30]. Available from http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/childhood_why/en/index.html.

Singhal V, Schwenk WF, Kumar S . Evaluation and management of childhood and adolescent obesity. Mayo Clin Proc 2007; 82: 1258–1264.

Pulgaron ER . Childhood obesity: a review of increased risk for physical and psychological comorbidities. Clin Ther 2013; 35: A18–A32.

Abraham S, Collins G, Nordsieck M . Relationship of childhood weight status to morbidity in adults. HSMHA Health Rep 1971; 86: 273–284.

Wang Y . Cross-national comparison of childhood obesity: the epidemic and the relationship between obesity and socioeconomic status. Int J Epidemiol 2001; 30: 1129–1136.

Chen F, Wang Y, Shan X, Cheng H, Hou D, Zhao X et al. Association between childhood obesity and metabolic syndrome: evidence from a large sample of Chinese children and adolescents. PloS One 2012; 7: e47380.

Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH . Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. New Engl J Med 1997; 337: 869–873.

Karnik S, Kanekar A . Childhood obesity: a global public health crisis. Int J Prev Med 2012; 3: 1–7.

Dietz WH, Bandini LG, Gortmaker S . Epidemiologic and metabolic risk factors for childhood obesity. Prepared for the Fourth Congress on Obesity Research, Vienna, Austria, December 1988. Klin Padiatr 1990; 202: 69–72.

Cui Z, Huxley R, Wu Y, Dibley MJ . Temporal trends in overweight and obesity of children and adolescents from nine Provinces in China from 1991–2006. Int J Pediatr Obes 2010; 5: 365–374.

Wang Y, Mi J, Shan X, Wang QJ, Ge K . Is China facing an obesity epidemic and the consequences? The trends in obesity and chronic disease in China. Int J Obesity 2007; 31: 177–188.

Fu J, Liang L, Zou C, Hong F, Wang C, Wang X et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in Zhejiang Chinese obese children and adolescents and the effect of metformin combined with lifestyle intervention. Int J Obesity 2007; 31: 15–22.

Li Y, Hu X, Zhang Q, Liu A, Fang H, Hao L et al. The nutrition-based comprehensive intervention study on childhood obesity in China (NISCOC): a randomised cluster controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2010; 10: 1.

Wang Y, Cai L, Wu Y, Wilson RF, Weston C, Fawole O et al. What childhood obesity prevention programmes work? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2015; 16: 547–565.

Wang Y, Tussing L, Odoms-Young A, Braunschweig C, Flay B, Hedeker D et al. Obesity prevention in low socioeconomic status urban African-american adolescents: study design and preliminary findings of the HEALTH-KIDS Study. Eur J Clin Nutr 2006; 60: 92–103.

Wang Y, Wu Y, Wilson RF, Bleich S, Cheskin L, Weston C et al. Childhood Obesity Prevention Programs: Comparative Effectiveness Review and Meta-Analysis. AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews: Rockville (MD), 2013.

Gortmaker SL, Peterson K, Wiecha J, Sobol AM, Dixit S, Fox MK et al. Reducing obesity via a school-based interdisciplinary intervention among youth: Planet Health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1999; 153: 409–418.

Xu F, Ware RS, Tse LA, Wang Z, Hong X, Song A et al. A school-based comprehensive lifestyle intervention among chinese kids against obesity (CLICK-Obesity): rationale, design and methodology of a randomized controlled trial in Nanjing city, China. BMC Public Health 2012; 12: 316.

Xu F, Ware RS, Leslie E, Tse LA, Wang Z, Li J et al. Effectiveness of a randomized controlled lifestyle intervention to prevent obesity among Chinese primary school students: CLICK-Obesity Study. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0141421.

Kipping RR, Howe LD, Jago R, Campbell R, Wells S, Chittleborough CR et al. Effect of intervention aimed at increasing physical activity, reducing sedentary behaviour, and increasing fruit and vegetable consumption in children: active for Life Year 5 (AFLY5) school based cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2014; 27: g3256.

Hoffmann TC Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014; 7: g1687.

Chu W, Wang Z, Zhou H, Xu F . The reliability and validity of a physical activity questionnaire in Chinese children. Chin J Dis Control Prev 2014; 18: 1079–1082.

Wang W, Cheng H, Zhao X, Zhang M, Chen F, Hou D et al. Reproducibility and and valididty of a food frequency questionnaire developed for children and adolescents in Beijing. Chin J Child Health Care 2016; 24: 8–11.

Reports on the Physical Fitness and Health Research of Chinese School Students in 2010. Higher education press: Beijing, China, 2012.

Group of China Obesity Task Force. Body mass index reference norm for screening overweight and obesity in Chinese children and adolescents. Chin J Epidemiol 2004; 25: 97–102.

Cai L, Wu Y, Cheskin LJ, Wilson RF, Wang Y . Effect of childhood obesity prevention programmes on blood lipids: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2014; 15: 933–944.

Epstein LH, Myers MD, Raynor HA, Saelens BE . Treatment of pediatric obesity. Pediatrics 1998; 101: 554–570.

Summerbell CD, Waters E, Edmunds L, Kelly S, Brown T, Campbell KJ . Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; 3.

Nemet D, Barkan S, Epstein Y, Friedland O, Kowen G, Eliakim A . Short-and long-term beneficial effects of a combined dietary–behavioral–physical activity intervention for the treatment of childhood obesity. Pediatrics 2005; 115: e443–e449.

Jiang J, Xia X, Greiner T, Wu G, Lian G, Rosenqvist U . The effects of a 3‐year obesity intervention in schoolchildren in Beijing. Child Care Health Dev 2007; 33: 641–646.

Li G, Zhang P, Wang J, Gregg EW, Yang W, Gong Q et al. The long-term effect of lifestyle interventions to prevent diabetes in the China Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study: a 20-year follow-up study. Lancet 2008; 371: 1783–1789.

Trevino RP, Yin Z, Hernandez A, Hale DE, Garcia OA, Mobley C . Impact of the Bienestar schoolbased diabetes mellitus prevention program on fasting capillary glucose levels: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2004; 158: 911–917.

Hendy HM, Williams KE, Camise TS . Kid's Choice Program improves weight management behaviors and weight status in school children. Appetite 2011; 56: 484–494.

Brandstetter S, Klenk J, Berg S, Galm C, Fritz M, Peter R et al. Overweight prevention implemented by primary school teachers: A randomized controlled trial. Obes Facts 2012; 5: 1–11.

Siegrist M, Lammel C, Haller B, Christle J, Halle M . Effects of a physical education program on physical activity, fitness, and health in children: The JuvenTUM project. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2013; 23: 323–330.

Singhal N, Misra A, Shah P, Gulati S . Effects of controlled school-based multi-component model of nutrition and lifestyle interventions on behavior modification, anthropometry and metabolic risk profile of urban Asian Indian adolescents in North India. Eur J Clin Nutr 2010; 64: 364–373.

Acknowledgements

The study (both the research project and intervention) was supported by Nanjing Medical Science and Technique Foundation (ZDX12019), China. Zhengqi Tan, Drs Youfa Wang and Hong Xue’s efforts were partially supported by the National Institute of Health (NIH, U54 HD070725). Professor Neville Owen was supported by NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence Grant #1057608, NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship #1003960 and by the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program. Our special thanks go to Professor Arne Ljungqvist (the former Chair of the Medical Commission, International Olympic Committee) and Professor Richard Budgett (the Director of Medical and Scientific Department, International Olympic Committee) for their suggestion on conducting a health legacy project of the 2nd World Summer Youth Olympic Games and review of the study proposal. We are also grateful to the advisory members from International Olympic Committee and all the workers, study participants and the school personnel that participated in the data collection. Dr Fei Xu had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The ABSTRACT has been shown as an oral presentation at The Lancet—China Diabetes Society session in November 2016, and has been published in a Supplementary issue of The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology. It also has been presented as a poster presentation at the 28th International Congress of Pediatrics in 17–22 August in Vancouver, Canada. Trial registration: Chinese Clinical Trial Registry: ChiCTR-ERC-11001819.

Author contributions

Conceived, designed and directed the study: FX (the PI of the project). Performed the experiments: FX, ZW (the project manager), QY, LAT (Co-PI) and YW (Co-PI). Analyzed the data: FX, QY, ZT, HX and YW. Wrote the article: FX, ZW, LAT, HX, YW, EL and NO. Critical revision of the manuscript: FX, LAT, HX, ZW, YW, EL and NO.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Xu, F., Ye, Q. et al. Childhood obesity prevention through a community-based cluster randomized controlled physical activity intervention among schools in china: the health legacy project of the 2nd world summer youth olympic Games (YOG-Obesity study). Int J Obes 42, 625–633 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2017.243

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2017.243

This article is cited by

-

Childhood obesity prevention policies in Iran: a policy analysis of agenda-setting using Kingdon’s multiple streams

BMC Pediatrics (2021)

-

How effective are physical activity interventions when they are scaled-up: a systematic review

International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity (2021)

-

The effectiveness of pediatric obesity prevention policies: a comprehensive systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials

Journal of Translational Medicine (2020)

-

A sex/gender perspective on interventions to promote children’s and adolescents’ overall physical activity: results from genEffects systematic review

BMC Pediatrics (2020)

-

Effectiveness of a school-based pilot program on ‘diabesity’ knowledge scores among adolescents in Chennai, South India

International Journal of Diabetes in Developing Countries (2020)