Abstract

Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved lysosomal self-digestion process involved in degradation of long-lived proteins and damaged organelles. In recent years, increasing evidence indicates that autophagy is associated with a number of pathological processes, including cancer. In this review, we focus on the recent studies of the evolutionarily conserved autophagy-related genes (ATGs) that are implicated in autophagosome formation and the pathways involved. We discuss several key autophagic mediators (eg, Beclin-1, UVRAG, Bcl-2, Class III and I PI3K, mTOR, and p53) that play pivotal roles in autophagic signaling networks in cancer. We discuss the Janus roles of autophagy in cancer and highlighted their relationship to tumor suppression and tumor progression. We also present some examples of targeting ATGs and several protein kinases as anticancer strategy, and discuss some autophagy-modulating agents as antitumor agents. A better understanding of the relationship between autophagy and cancer would ultimately allow us to harness autophagic pathways as new targets for drug discovery in cancer therapeutics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Autophagy, a term from Greek “auto” (self) and “phagy” (to eat), refers to an evolutionarily conserved catabolic process in which a cell degrades long-lived proteins and damaged organelles, such as the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, and mitochondria. Autophagy serves as a critical adaptive response to starvation (amino acid and nutrient deprivation) and metabolic stress by recycling energy and nutrient. According to the mode of delivery to lysosome, three types of autophagy have been identified, namely macroautophagy, microautophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy1. In this review, we mainly focus on the most widely investigated process: macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy).

Autophagy is a multi-step process highly regulated by a number of the conserved autophagy-related genes (ATGs). Originally discovered in yeast, ATG genes were reported to play vital roles in autophagosome formation and autophagy regulation, and have been known to be associated with several important pathological process such as cancer initiation and progression2. Numerous links between autophagy and cancer have emerged and appeared to be multifaceted. Under some circumstances, autophagy can function as a tumor suppressor via eliminating damaged cells. On the another hand, the cytoprotective role of autophagy can indirectly protect cells from carcinogenesis by maintaining genomic stability and homeostasis3. Paradoxically, the cytoprotective effects of autophagy may contribute to tumor development under stress. Recent studies have indicated that autophagy can play a key role in tumor cell resistance to chemotherapy, and inhibition of autophagy can enhance the cytotoxicity of certain chemotherapeutic agents4, 5. All these studies unveil an intricate relationship between autophagy and cancer. In this review, we will discuss the relationship between autophagy and cancer, and evaluated several drugs that target autophagy pathways at a molecular level, in the hope of shedding some light on cancer drug discovery via targeting autophagic signaling pathways.

Molecular basis of autophagy

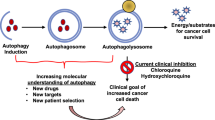

The delineation of molecular mechanisms of autophagy originated from the year of 1993 when the ATGs were first identified in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae6. It is well known that the molecular basis of autophagy is conserved from yeast to mammals, and the orthologs of most of the yeast ATGs have been discovered in mammalian cells. The complete autophagic flow is a highly regulated multi-step process which, in general, can be divided into several stages, including induction, vesicle nucleation, vesicle elongation and completion, docking and fusion, degradation and recycling7, 8, 9 (Figure 1).

Autophagy can be induced by a variety of stimuli (eg, nutrient deprivation, hypoxia, cytokines, hormones, and DNA damage), and the induction of autophagy is, in most cases, associated with the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) which is a central controller of cell growth10. In yeast, Tor signaling can negatively regulate Atg1 and Atg13, and the association of which is required for the early activation of autophagy11.

The vesicle nucleation is mediated by activation of Class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3KCIII), an ortholog of Vps3412. The activity of Vps34 is regulated by a complex consisting of Beclin1 (a mammalian ortholog of Atg6) and the myristylated serine kinase Vps15/p15013. Two PI3KCIII positive mediators, ultraviolet irradiation resistance-associated gene (UVRAG) and Bif-1, can enhance PI3KIII activity by interacting with Beclin114, 15. In yeast, Atg14 can direct Vps34 complex to pre-autophagosomal structure (PAS)16. Although the mammalian ortholog of Atg14 has been identified, its functions have not been clarified yet in mammalian cells17. In the vesicle nucleation step, PI3P produced by PI3KIII plays an important role by binding and recruiting PX and FYVE domain-containing proteins such as Atg18-Atg2 complex18, 19, 20.

The vesicle elongation and completion process requires two ubiquitin-like pathways involving two ubiquitin-like proteins, Atg12 and Atg8 proteins, respectively. The first pathway includes an Atg12-Atg5 covalently conjugating system, and subsequently the formation of which requires an E1- and E2- like proteins Atg7 and Atg10, respectively21, 22, 23. In mouse, the Atg12-Atg5 conjugate interacts with a small coiled-coil protein, Atg16L (an ortholog of Atg 16 in yeast), to form an Atg12-Atg5-Atg16L complex. In conjunction with Atg12-Atg5, Atg16L directs the complex to autophagic isolation membrane, and it is essential for the second pathway and autophagosome formation24. The second ubiquitin-like pathway involves LC3 (mammalian ortholog of Atg8) lipidation that plays an essential role in membrane dynamics during autophagy25. As soon as Atg8 is translated, the carboxy-terminal Arg residue of Atg8 is cleaved off by a cysteine protease, Atg4, exposing a critical Glycine residue at the C terminus26. Mediated by an E1 protein Atg7 and an E2 protein Atg3, Atg8 is then covalently conjugated to phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) through an amide bond between the C-terminal glycine and the amino group of phosphatidylethanolamine25. Lipidation of Atg8 converts the soluble Atg8 (mammalian LC3-I) into a membrane bound, autophagosome associated form (mammalian LC3-II), which represents an important biomarker of autophagy. In this manner, Atg8 proteins recruit lipid molecules to expand autophagosome membrane. Targeting Atg8 to isolate membrane needs the Atg12-Atg5-Atg16 complex27; however, the Atg12-Atg5 conjugate can act as an E3-like enzyme for Atg8-PE conjugate reaction, promoting the lipidation of Atg828. Once the autophagosome expansion is complete, Atg8 detaches from PE under the assistance of Atg4 and then released to cytosol26. Additionally, autolysosome maturation is derived from docking and fusion of autoghagosome with endolysosomal compartments, leading to the breakdown of autophagosomal contents. Successful docking and fusion rely on microtubules and endolysosomal molecules, such as small GTPase Rab7, lysosomal-associated proteins 1 and 2 (LAMP1 and LAMP2), AAA ATPase SKD1, SNARE protein Vti1b, and ESCRT complex29, 30, 31. Some autophagy mediators such as UVRAG, functioning in the early steps, can regulate autophagosome maturation32. After docking and fusion, the autophagosomal cargoes are digested by acidic hydrolases, and then nutrient and energy are recycled.

Canonical autophagic signaling pathways in cancer

Although the molecular basis of autophagy was discovered from the year of 1993, a link between autophagy and cancer was established in 1999 when the ATG gene Beclin1 was found to inhibit tumorigenesis and assumed to be a candidate tumor suppressor33. Since then, increasing number of ATGs have been found to be oncogenes or tumor suppressors and thus their related autophagic pathways are involved in cancer. Here, we will discuss some major autophagic regulators and related pathways in cancer.

Beclin 1 and its mediators

Beclin 1, the mammalian homolog of Atg6 and a Bcl-2 interacting coiled-coil protein, is a haploinsuffcient tumor suppressor gene34, 35. It has been reported to be mono-allelically deleted in 75% of ovarian, 50% of breast and 40% of prostate cancers36. Gene-transfer of Beclin-1 could promote autophagy in human MCF7 breast carcinoma cells, but inhibited MCF7 cellular proliferation33. Heterozygous disruption of Beclin 1 could result in increased cellular proliferation and reduced autophagy in vivo34. These findings suggest that autophagy-promoting activity of Beclin 1 is tightly associated with its tumor suppression function. As mentioned above, Beclin 1 can enhance autophagy by combining with PI3KIII/Vps34 in the initiating stage of autophagy. An evolutionarily conserved domain (ECD) of Beclin 1 has also been reported to interact with PI3KIII/Vps34 (Figure 2B). A Beclin 1 mutant lacking ECD was unable to enhance autophagy and lost its tumor suppressor function, which further supported the notion that autophagy promotion and tumor inhibition function of Beclin-1 was interconnected37. Furthermore, the tumor suppressor function of Beclin 1 is supported by the identification of its mediators that are implicated in tumorigenesis. UVRAG, a major Beclin 1 positive mediator, can interact with Beclin 1 via their coiled-coil domain (Figure 2B). By interacting with Beclin1, UVRAG markedly enhances PI3KC3 lipid kinase activity, thereby facilitating autophagy32. Similar to Beclin 1, UVRAG is monoallelically mutated in various human colon cancer cells and tissues38. Through mediating Beclin 1- PI3KIII complex, UVRAG can promote autophagy, thus inhibiting tumorigenesis of human colon cancer cells32.

Bif-1, another Beclin 1 positive mediator, can interact with Beclin 1 through UVRAG (Figure 2B) to regulate autophagy and suppress tumorigenesis. Consistently, it has been reported that loss of Bif-1 suppressed autophagosome formation and significantly enhanced the development of spontaneous tumor in mice15. In addition, downregulation of Bif-1 was also found in prostate, colon, invasive urinary bladder, gallbladder and gastric cancers39, 40, 41, 42. Although the precise mechanisms of Bif-1 in suppressing tumor have not been fully clarified, it is reasonable to presume that the tumor inhibitory activity of Bif-1 is associated with its roles in regulating autophagy.

There also exist a number of Beclin 1 negative regulators that involve an important protein family, Bcl-2 family. Bcl-2 family is comprised of B cell CLL/lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) and its relatives, and is originally characterized as a controller of outer mitochondrial membrane integrity and apoptosis. These proteins are functionally classified as either antiapoptotic or proapoptotic proteins43. Antiapoptotic Bcl-2 members (such as Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL) contain four Bcl-2 homology domains (BH), while proapoptotic Bcl-2 proteins can be further divided into the effector proteins (such as Bax and BAK) that contain three BH domains and the BH3-only proteins (such as BAD and Noxa). Here we will focus on Bcl-2, an oncogene which negatively regulates Beclin 1-PI3KIII/Vps34 complex and autophagy. For almost two decades, Bcl-2 has been regarded to function by inhibiting apoptosis. It was until 1998 when Liang, et al identified a Bcl-2 interacting, Beclin 1, that the role of Bcl-2 in autophagy was uncovered33. Subsequently, further evidence showed that down-regulation of Bcl-2 could induce autophagy in a caspase-independent manner in human leukemic HL60 cells44, and the transfer of Bcl-2 in mice could restrain starvation-induced autophagy in cardiac muscle in vivo45. Bcl-2 inhibits autophagy through interacting with Beclin 1. Beclin 1 contains a BH3 domain that contributes to the association of Beclin 1 with the BC groove of Bcl-2 (shown in Figure 2A and 2B)46, 47. Accordingly, mutations in BH3 domain of Beclin 1, or BH3 receptor domain of Bcl-2 would abolish the Bcl-2 mediated inhibition of autophagy46. By interacting with Beclin1, Bcl-2 blocked Beclin 1 interaction with PI3KIII/Vps34, decreased PI3KIII activity and downregulated autophagy45. However, the precise mechanisms by which Bcl-2 blocks Beclin 1 and PI3KIII/Vps34 interaction, either through disassociating the Beclin 1- PI3KIII/Vps34 or inhibiting its activity, is unclear. In spite of this, the binding of Bcl-2 with Beclin 1 seems to be constitutive, and its detachment from Beclin 1 is speculated to be essential in autophagy induction. Two models were proposed to explain Beclin 1 release from Bcl-2. The first model suggests that disassociation of Beclin 1 with Bcl-2 depends on the phosphorylation of Bcl-2 or Beclin 1. It was demonstrated that the c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase 1 (JNK1) could phosphorylate Bcl-2 in its non-structural N-terminal loop48, 49. Moreover, a recent study has shown that DAP-kinase mediated phosphorylation in the BH3 domain of Beclin 1 can weaken its interactions with Bcl-2, leading to an elevation of autophagy50. The second model involves the replacement of Beclin 1 from Bcl-2 by BH-only proteins. Upon starvation, BAD, a typical BH3-only protein, could competitively displace Beclin 1 from Bcl-2, and, supportive of this, bad-deficient mice bear a decreased level of autophagy51.

In general, Beclin 1 can enhance autophagy and inhibit tumorigenesis by forming a Beclin 1- PI3KIII/Vps34 complex, mediated by its positive regulators, UVRAG and Bif-1, as well as its negative regulators, Bcl-2. Beclin 1 acts as a platform to recruit and activate PI3KIII/Vps34, suggesting a crucial role in autophagy and tumorigenesis.

Class III and I PI3K

The phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) family, which can phosphorylate the 3′OH group of phosphatidylinositols, regulates various cellular activities including autophagy52, 53. According to the distinct substrate specificities and lipid products, PI3K family can be divided into three classes, among which Class III and Class I PI3K are the most widely implicated classes in autophagy and cancer. Intriguingly, the roles of Class III and Class I PI3K are quite opposite in autophagy, in which Class III PI3K accelerates autophagy, whereas Class I PI3K inhibits it.

PI3KIII plays an important role in the vesicle nucleation step of autophagy process. And, PI3KIII associates with PAS under the direction of Atg14, and then the lipid products of PI3KIII, PI3P, mediates docking of PX and FYVE domain-containing proteins to the nucleation sites18, 19, 20. PI3KIII exerts its effect by forming a complex with Beclin 1 and Vps15/p150, both of which are positive regulators of PI3KIII13. UVRAG and Bcl-2 can also regulate PI3KIII complex activity by interacting with Beclin 1, thus regulating autophagy.

Conversely, Class I PI3Ks inhibit autophagy through a PDK1 and Akt/PKB pathway, which is inappropriate activated in many types of cancers. Class I PI3Ks are heterodimers, consisting of a p85 regulatory and p110 catalytic subunit. Following growth factors binding to the cell surface receptors, which, in most cases, are receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), Class I PI3Ks are activated. The p85 regulatory subunit is essential in RTKs-mediated activation of Class I PI3Ks by binding with activated RTKs through its Src-homology 2 (SH2) domains54. By binding with RTKs, p85-p110 deterodimer is recruited to the membrane where its substrates PI3, 4-diphosphate (PIP2) residues, and meanwhile, the basal inhibition of p85 on p110 is alleviated55. After being recruited to the membrane, Class I PI3Ks phosphorylate PIP2 to generate the second messenger phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3). This process can be inhibited by a tumor suppressor PTEN, which dephosphorylates PIP3 and terminates PI3K signaling56. Then, the accumulated PIP3 recruits PDK1 and Akt through their Pleckstrin homology (PH) domains, where Akt is fully activated through phosphorylation by PDK1 at T308 and by mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2) at S47357. Furthermore, activated Akt promotes cell survival through phosphorylation of several cellular proteins, including MDM2, glycogen synthase kinase 3α (GSK3α), GSK3β, fork-head box O transcription factors (FoxO), tuberous sclerosis 2 (TSC2), BCL2-interacting mediator of cell death (BIM) and BCL2-associated agonist of cell death (BAD)53, 58, 59, 60, 61. MDM2 activation by Akt enhances p53 ubiquitination and degradation, thus promoting cell survival. Additionally, Akt phosphorylation leads to FoxO exclusion from nuclear and blocks transcriptional induction of death-related genes. Furthermore, TSC2, a GTPase-activating protein for Ras homologue enriched in brain (Rheb), is also inactivated by Akt, which allows Rheb accumulation and thereby activates mTORC162, 63. Akt has also been suggested to activate mTORC1 by lowering cellular AMP/ATP level and hence inhibit AMPK activity64. mTORC1, one of the major downstream effectors of Akt, plays central roles in autophagy regulation.

The PI3KI-Akt pathway is activated aberrantly in many types of cancers, revealing its vital role in growth and proliferation of cancer cells65. Hitherto, two mechanisms have been most widely observed, which leads to the inappropriate activation of PI3KI-Akt in cancer, namely activation by receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) and somatic mutations in specific components of the signaling pathways. In various cancers, RTKs, such as EGFR, HER2, and PDGFR, activate PI3K and all these types of cancers are invariably resistant to a single RTK inhibitor, suggesting RTK is a potential oncogene66, 67, 68. Somatic mutations in PIK3CA gene encoding the p110alpha catalytic subunit frequently occurs in cancers of the colon, breast, brain and lung69, and in vitro and in vivo experimental data have confirmed the involvement of these mutations in tumorigenesis70, 71, 72. In addition, the PI3KI-Akt signaling pathway is also regulated by several tumor-related genes, which indirectly reflects its key role in tumor development. One of the regulators is Ras, which is involved in cell growth signaling and may lead to oncogenesis and cancer. It has been reported that p110 catalytic subunit of PI3KI can bind with Ras, linking PI3KI-Akt pathway with Ras signaling. PTEN, another regulator of PI3KI-Akt pathway, is a tumor suppressor that is found to be mutated in human brain, breast, and prostate cancer, can negatively regulate the pathway by degrading the lipid product of PI3KI73, 74. Taken together, Class III and I PI3K play the key roles in regulating autophagy and cancer pathogenesis, and targeting these pathways may represent an attractive strategy for cancer therapy.

mTOR Pathway

The target of rapamycin, TOR (mTOR in mammals), is an evolutionarily conserved serine/threonine kinase that regulates a variety of cellular processes, including cell growth, cell cycle, proliferation, and autophagy75. In mammals, mTOR exists in two different complexes, known as mTORC1 which contains a raptor, and mTORC2 which contains a rictor. However, only mTORC1 is sensitive to rapamycin while mTORC2 is not; therefore, we will focus on mTORC1 and its relevance to autophagy76.

mTORC1 occupies a central position in protein synthesis and autophagy repression, and exerts its role through integration of different signal inputs, including growth factor signaling, cytokines, nutrient and metabolic stresses (ATP/AMP ratio and O2 availability). To date, three major mTORC1-inducing pathways have been clarified. Two of them are PI3K-Akt pathway and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-90-kDa ribosomal S6 kinase (RSK)-death-associated protein kinase (DAPK) kinase cascades, which can activate mTORC1 and suppress autophagy. The third one is an mTORC1 inhibitory pathway via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3). Of note, the signaling pathways promoting mTORC1 activity is often induced by oncoproteins and/or loss of tumor suppressors, and hence mTORC1-inhibited autophagy is often observed in cancer cells30.

Most of the signaling pathways regulating autophagy converge upstream of mTORC1 at the TSC2/TSC1 complex, the tumor suppressors observed to be mutated in a variety of cancers. As mentioned above, the TSC2/TSC1 complex suppresses mTORC1 by inactivating mTORC1-interacting protein, Rheb. Upon PI3K activation, Akt phosphorylation of TSC2 destabilizes TSC2 and disrupts its interaction with TSC1, thus abolishing the negative regulatory effect of TSC2/TSC1 complex on mTORC177, 78. Similarly, ERK mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) and its downstream effectors, RSK and DAPK, can inactivate TSC2 through phosphorylation and allow Rheb activation of mTORC179, 80, 81. In contrast, phosphorylation of TSC2 by AMPK increases its GTPase activity, stabilizes the TSC2/TSC1 complex, and inactivates Rheb, leading to inactivation of mTORC1 and thus triggering autophagy86. Originally, AMPK was defined as an intracellular energy status sensor, detecting and responding to the changes in AMP/ATP ratios. High intracellular AMP level allows serine-threonine kinase, liver kinase B1 (LKB1), a tumor suppressor mutated in Peuz-Jeghers syndrome, to phosphorylate AMPK, thus providing starved cells with nutrient by inducing autophagy82. Remarkably, the initiation of autophagy by AMPK is not limited to the starvation-induced activation of LKB1. Recent studies have demonstrated that AMPK can mediate autophagy in response to the cytosolic Ca+ concentration and cytokines via Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase kinase-b (CaMKKb) and transforming growth factor-b-activating kinase 1 (TAK1) pathways, respectively83, 84. Moreover, genotoxic stresses trigger AMPK-mediated autophagy in a p53-dependent manner85.

Downstream executors of mTORC1 involve a number of autophagy-related genes and proteins implicated in cell physiology and cancer pathology. In yeast, mTORC1 hyperphosphorylates Atg13, reducing its affinity with Atg1 under nutrient rich condition. Disassociation of Atg13 attenuates Atg1 activity, which is essential for autophagy initiation11. In mammals, two homologs of Atg1, uncoordinated 51-like kinase 1 (ULK1) and ULK2, Atg13 and the scaffold protein FIP200 (an ortholog of yeast Atg17) have been identified86, 87, 88, 89. By phosphrylation of ULK and Atg13 in a nutrient starvation-regulated manner, mTORC1 disrupts the binding of Atg13 with ULK and destabilizes ULK, inhibiting the ULK-dependent phosphorylation of FIP200 and autophagy induction90, 91, 92, 93. Although the mechanism of ULK-Atg13-FIP200 complex in autophagy initiation is not fully understood, it is speculated that activated FIP200 localizes ULK to PAS where it regulates vesicle nucleation by recruitment of other Atg proteins to that location, as Atg17 does in yeast94. Therefore, through ULK complex, mTORC1 establishes a link with the core autophagy machinery in mammals, thus regulating autophagy more directly.

mTORC1 can also regulate autophagy by mediating protein translation and cell growth through 4E-BP1 and p70S6K phosphorylation. Phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 leads to its detachment of from the RNA cap-binding protein eIF4E and upregulates cap-dependent translation95. On the contrary, phosphoryaltion of p70S6K enhances its activity and facilitates its phosphorylatory effect on the targets. p70S6K phosphorylates a wide spectrum of proteins implicated in transcription and translational apparatus, including 40S ribosomal protein S6 and eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase (eEF2K), etc. p70S6K phosphorylates eEF2K at a conserved serine and inhibits its activity, thus relieving eEF2 from the negative regulation by eEF2K and promoting protein translation96. In addition to S6 and eEF2K, p70S6K can promote cell survival and growth by inhibiting a proapoptotic BH3-only protein Bad97. Of note, p70S6K activity can be downregulated by ULK1, ULK2 and Atg13, indicating that existence of a positive-feedback loop may enhance nutrient-dependent autophagy92. These findings suggest that mTORC1 occupies a central position in autophagy-regulated network. Obviously, numerous oncogenes and tumor suppressors are incorporated in mTORC1-centered signaling network, suggesting a close, complex connections between those oncogenes and tumor suppressors with cancer.

p53

The transcriptional factor p53 is a well known tumor suppressor protein, but is found to be mutated in more than 50% of human cancers. p53 becomes activated in response to a myriad of stresses, including DNA damage, oxidative stress and etc. In mammalian cells, two forms of p53 exist, namely cytoplasm p53 and nucleus p53. Following activation, cytoplasm p53 translocates to the nucleus and regulates the target genes expression, resulting in DNA repair, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Recently, p53 has been reported to participate in autophagy regulation; however, the role of p53 in autophagy seems to be paradoxical depending on its different subcellular location.

In nucleus, p53 facilitates autophagy mainly by interacting with its targets, damage-regulated autophagy modulator (DRAM) and sestrin1/2. The direct link between p53 and autophagy was unknown until DRAM, a p53 target gene encoding a lysosomal protein that induces macroautophagy, was discovered to be an effector of p53-mediated cell death98. DRAM can trigger autophagy under the control of p53 in response to DNA damage agents. The expression of DRAM is down-regulated in a subset of epithelial cancers via direct hypermethylation within the DRAM, indicative of DRAM as a tumor suppressor98. Other targets of DRAM, Sestrin1 and sestrin2, whose expressions are usually induced upon DNA damage and oxidative stresses, are negative regulators of mTORC1, and execute their function through activation of AMPK and TSC complex98. Consistently, disruption of Sestrin2 in mice attenuated its ability to inhibit mTOR signaling upon genotoxic challenge99. Thus, sestrin establishes a connection between p53 and autophagy through mTORC1 signaling pathway, providing another molecular mechanism for p53-mediated tumor suppression.

Different from nucleus p53, cytoplasm p53 has been found to inhibit autophagy independent of its role as a transcriptional factor100. Correspondingly, depletion or inhibition of p53 is able to induce autophagy in human, mouse and nematode cells subjected to knockout, knockdown or pharmacological inhibition of p53. More important, enhanced autophagy may favor survival of the p53-deficient cancer cell under nutrient depletion and hypoxia, suggesting the involvement of autophagy in cancer-associated dysregulation of p53 and its cytoprotective role.

These reported studies demonstrate how cancer-related pathways regulate autophagy. Importantly, these signaling pathways do not function independently; instead, they execute their roles in an overlapping way, forming a network implicated in both autophagy and cancer (Figure 3). These signaling pathways possess different functions and roles, implying a paradoxical role of autophagy in cancer.

The Janus role of autophagy in cancer therapy

Cancer cells often display a reduced capacity of autophagy by inactivation of proautophagic genes like LKB1, PTEN, p53, TSC1, TSC2, Beclin 1, UVRAG, and Bif-1, as well as activation of antiautophagic genes such as PI3KCI, Akt, Ras, and Bcl-23, 101, 102. The above-mentioned evidence suggests that autophagic activity are often suppressed in cancer cells and autophagy may act as a tumor suppressor in oncogenesis, and thus induction of autophagy may help transform tumor phenotype in cancer therapy. Nevertheless, under certain conditions, enhanced autophagy is observed in tumor cells, suggesting its pro-survival roles in cancer. In support of this, lysosomes that are essential in autophagy cargoes degradation show significantly higher activity during tumorigenesis101. Utilizing autophagy as a cytoprotective mechanism, tumor cells manage to survive in harsh microenvironment. In response to many anticancer therapies such as chemotherapy, histone deaceltylase inhibitors, arsenic trioxide, TNF-α, IFNγ, imatinib, rapamycin, and antiestrogen hormonal therapy, autophagy is induced as a pro-survival strategy in human cancer cells103, 104. Under these circumstances, inhibition of autophagy may lead to increased cell death and decreased tumor cell growth.

Additionally, it has been reported that autophagy is able to induce type II programmed cell death in the absence of apoptosis. Bax-/- and Bak-/- knockout fibroblast cells, which are resistant to apoptosis, and undergo autophagic cell death following nutrient and growth factor deprivation, chemotherapy or radiation stimuli105, 106. In various cancer cells, apoptosis is blocked and autophagy may serve as a major mechanism to induce cancer cell death; thus, the induction of autophagy may be used as a promising therapeutic strategy in cancer treatment. These findings may reveal an intricate relationship between cancer and autophagy. Although the relative balance of pro-death and pro-survival roles of autophagy in carcinogenesis and cancer remains an enigma, some hypotheses have been proposed to alleviate this puzzle. One hypothesis suggests that roles of autophagy vary depending on the different stages of tumor development102. For instance, autophagy limits tumor formation in the early stage, while favors tumor cell survival and invasion as soon as cancer has formed. Another hypothesis proposes that autophagy can regulate tumorigenesis in a cell- and tissue-specific manner107, 108. Thus, the relationship between autophagy and cancer remains unclear; nevertheless, considering their intimate relations, targeting autophagic signaling pathways makes sense and may be promising in cancer treatment.

Targeting autophagic signaling pathways in cancer treatment

Hitherto, the underlying molecular mechanisms of autophagy regulation have remained to be elucidated; however, several novel emerging strategies are being used to target autophagic signaling pathways for drug discovery in cancer treatment. Autophagy-related genes (ATGs) play the key roles in the formation of the autophagosome and the regulation of autophagy, which are closely linked to cancer initiation and progression. Silencing several essential modulators of the autophagic machinery such as Atg3, Atg4b, Atg4c, Bec-1/Atg6, Atg10, and Atg12 have been shown to sensitize cancer cells to a wide spectrum of stress conditions109, 110. Accordingly, this strategy may be a useful approach for targeting protective autophagy in cancer therapeutics.

Targeting selected protein kinases involved in the regulation of autophagy using small molecule inhibitors may be another feasible approach in cancer therapy. Recently, a number of protein kinases have been known to regulate the induction of autophagy following nutrient deprivation or other cellular stresses; thus, only the following protein kinases have been reported to induce protective autophagy in response to cytotoxic agents in cancer cells, eg, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) beta, extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) and eukaryotic elongation factor-2 kinase (eEF2K). On the other hand, other protein kinases are involved in the promotion of autophagy, but not yet evaluated as the potential therapeutic targets, including death-associated protein kinase (DAPK) and Unc-51-like kinase 1 (ULK-1)110. While further studies should be necessary to evaluate the precise functions of the protein kinases, these selected protein kinases would represent potentially promising targets for cancer therapeutics.

Autophagy is not only a survival response to either growth factor or nutrient deprivation, but also an important mechanism for tumor cell suicide111. Recently, the increasing data have accumulated to signify autophagy as a mechanism of type II programmed cell death (PCD), and present new perspectives for developing alternative anti-cancer therapies112. Thus, several autophagy-inducing agents are already being used in the treatment of different human cancers, and would be further explored from bench to clinic. Recently, imatinib (gleevac) has been found to induce autophagy in multi-drug-resistant Kaposi's sarcoma cells as part of its mode of action and also be effective in the treatment of glioblastomas113. Moreover, histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDAC), such as suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA), have also been reported to induce autophagy in Hela cells and is independent of caspase activation and apoptosis. Thus, initiation of autophagic cell death by SAHA has clear therapeutic implications for apoptosis-defective tumors. Furthermore, it is well-known that mTOR is a major regulator of cell growth that has been implicated in tumorigenesis114. Rapamycin, which binds the 12 kDa immunophilin FK506-binding protein (FKBP12) and inhibits the mTORC1complexis, and its derivatives, CCI-779 and RAD001, have been used in clinical trials for the treatment of cancer. Recent evidence have indicated that tumor-suppression following rapamycin treatment is linked to the induction of autophagic cell death. mTOR inhibitors have been reported to sensitize various tumor cells to radiation therapy115. For example, combined treatment of RAD001 with the caspase-3 inhibitor DEVD radio-sensitized non-small cell lung cancer cells in mouse models, leading to enhanced cytotoxicity through induction of autophagy and to delayed tumor growth116. Thus, inhibition of mTOR by rapamycin or its derivatives provides a powerful therapeutic tool for the treatment of various malignancies.

In addition to these reported agents, there are also other interesting examples of the autophagy-inducing agents from traditional Chinese medicine in cancer treatment. Arsenic trioxide (As2O3), a classical toxin from the traditional Chinese medicine, has been reported to attribute to induction of apoptosis following cytochrome c release and caspase activation116. However, treatment of human T-lymphocytic leukemia cells with arsenic trioxide has been recently shown to cause cytotoxicity through induction of autophagy. The Bcl-2 family member, Bcl-2-adenovirus E1B 19-kDa-interacting protein 3 (BNIP3), is reported to play a pivotal role in arsenic trioxide-induce autophagic cell death in malignant glioma cells 117, 118. Polygonatum cyrtonema lectin (PCL) has been reported to induce autophagy via a mitochondria-mediated pathway and plays a death-promoting role in human melanoma A375 cells119. Subsequently, PCL-induced autophagy has been further confirmed to be a mitochondrial-mediated ROS-p38–p53 pathway120. Based upon the aforementioned examples, autophagy plays a prominent role in the cytotoxic effects of these compounds that may lead to a new therapeutic strategy whereby autophagy would be specifically induced to suppress carcinogenesis.

Concluding remarks

Cancer is a complex, multi-step human disease that is closely related to the Janus of autophagy. Currently, much work should be needed to determine the molecular mechanisms of autophagy in cancer, to define how the crucial modulators of autophagy in cancer impacts cancer initiation and progression, and to elucidate why targeting autophagic signaling pathways is promising for cancer therapeutics. However, due to the complex two-faced nature of autophagy, establishing the dual role of autophagy in tumor survival vs death may help in determining the cancer therapeutic potential. Inhibiting autophagy may enhance the efficacy of currently used anti-cancer drugs in chemo- and radiotherapy-induced activation of autophagic signaling pathways. On the contrary, promoting autophagy may induce cancer cell death with high thresholds to apoptosis. Therefore, both strategies have significant potential to be translated into ongoing clinical trials that may provide more valuable information on whether and how targeting autophagic signaling pathways makes sense in cancer treatment.

References

Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ . Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature 2008; 451: 1069–75.

Levine B, Kroemer G . Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell 2008; 132: 27–42.

Mathew R, Karantza-Wadsworth V, White E . Role of autophagy in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2007; 7: 961–67.

Abedin MJ, Wang D, McDonnell MA, Lehmann U, Kelekar A . Autophagy delays apoptotic death in breast cancer cells following DNA damage. Cell Death Differ 2007; 14: 500–10.

Carew JS, Nawrocki ST, Kahue CN, Zhang H, Yang C, Chung L, et al. Targeting autophagy augments the anticancer activity of the histone deacetylase inhibitor SAHA to overcome Bcr-Abl-mediated drug resistance. Blood 2007; 110: 313–22.

Tsukada M, Ohsumi Y . Isolation and characterization of autophagy-defective mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett 1993; 333: 169–74.

Fader CM, Colombo MI . Autophagy and multivesicular bodies: two closely related partners. Cell Death Differ 2009; 16: 70–8.

Eskelinen EL . New insights into the mechanisms of macroautophagy in mammalian cells. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 2008; 266: 207–47.

Yoshimori T, Noda T . Toward unraveling membrane biogenesis in mammalian autophagy. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2008; 20: 401–7.

Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN . TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell 2006; 124: 471–84.

Kamada Y, Funakoshi T, Shintani T, Nagano K, Ohsumi M, Ohsumi Y . Tor-mediated induction of autophagy via an Apg1 protein kinase complex. J Cell Biol 2000; 150: 1507–13.

Kihara A, Noda T, Ishihara N, Ohsumi Y . Two distinct Vps34 phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complexes function in autophagy and carboxypeptidase Y sorting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol 2001; 152: 519–30.

Stack JH, DeWald DB, Takegawa K, Emr SD . Vesicle-mediated protein transport: regulatory interactions between the Vps15 protein kinase and the Vps34 PtdIns 3-kinase essential for protein sorting to the vacuole in yeast. J Cell Biol 1995; 129: 321–34.

Liang C, Feng P, Ku B, Dotan I, Canaani D, Oh BH, et al. Autophagic and tumour suppressor activity of a novel Beclin 1-binding protein UVRAG. Nat Cell Biol 2006; 8: 688–99.

Takahashi Y, Coppola D, Matsushita N, Cualing HD, Sun M, Sato Y, et al. Bif-1 interacts with Beclin 1 through UVRAG and regulates autophagy and tumorigenesis. Nat Cell Biol 2007; 9: 1142–51.

Obara K, Sekito T, Ohsumi Y . Assortment of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complexes-Atg14p directs association of complex I to the pre-autophagosomal structure in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell 2006; 17: 1527–39.

Itakura E, Kishi C, Inoue K, Mizushima N . Beclin 1 forms two distinct phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complexes with mammalian Atg14 and UVRAG. Mol Biol Cell 2008; 19: 5360–72.

Wishart MJ, Taylor GS, Dixon JE . Phoxy lipids: Revealing PX domains as phosphoinositide binding modules. Cell 2001; 105: 817–20.

Gillooly DJ, Simonsen A, Stenmark H . Cellular functions of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate and FYVE domain proteins. Biochem J 2001; 355: 249–58.

Obara K, Sekito T, Niimi K, Ohsumi Y . The Atg18–Atg2 complex is recruited to autophagic membranes via phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate and exerts an essential function. J Biol Chem 2008; 283: 23972–80.

Mizushima N, Noda T, Yoshimori T, Tanaka Y, Ishii T, George MD, et al. A protein conjugation system essential for autophagy. Nature 1998; 395: 395–8.

Shintani T, Mizushima N, Ogawa Y, Matsuura A, Noda T, Ohsumi Y . Apg10p, a novel protein-conjugating enzyme essential for autophagy in yeast. EMBO J 1999; 18: 5234–41.

Tanida I, Mizushima N, Kiyooka M, Ohsumi M, Ueno T, Ohsumi Y, et al. Apg7p/Cvt2p: A novel protein-activating enzyme essential for autophagy. Mol Biol Cell 1999; 10: 1367–79.

Mizushima N, Kuma A, Kobayashi Y, Yamamoto A, Matsubae M, Takao T, et al. Mouse Apg16L, a novel WD-repeat protein, targets to the autophagic isolation membrane with the Apg12–Apg5 conjugate. J Cell Sci 2003; 116: 1679–88.

Ichimura Y, Kirisako T, Takao T, Satomi Y, Shimonishi Y, Ishihara N, et al. A ubiquitin-like system mediates protein lipidation. Nature 2000; 408: 488–92.

Kirisako T, Ichimura Y, Okada H, Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, et al. The reversible modification regulates the membrane-binding state of Apg8/Aut7 essential for autophagy and the cytoplasm to vacuole targeting pathway. J Cell Biol 2000; 151: 263–76.

Mizushima N, Yamamoto A, Hatano M, Kobayashi Y, Kabeya Y, Suzuki K, et al. Dissection of autophagosome formation using Apg5-deficient mouse embryonic stem cells. J Cell Biol 2001; 152: 657–68.

Hanada T, Noda NN, Satomi Y, Ichimura Y, Fujioka Y, Takao T, et al. The Atg12–Atg5 conjugate has a novel E3-like activity for protein lipidation in autophagy. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 37298–302.

Fass E, Shvets E, Degani I, Hirschberg K, Elazar Z . Microtubules support production of starvation-induced autophagosomes but not their targeting and fusion with lysosomes. J Biol Chem 2006; 281: 36303–16.

Kochl R, Hu XW, Chan EY, Tooze SA . Microtubules facilitate autophagosome formation and fusion of autophagosomes with endosomes. Traffic 2006; 7: 129–45.

Elisabeth A C, Pietri P, Marja J . Apoptosis and autophagy: Targeting autophagy signaling in cancer cells – 'trick or treats'? FEBS J 2009; 276: 6084–96.

Liang C, Lee JS, Inn KS, Gack MU, Li Q, Roberts EA, et al. Beclin1-binding UVRAG targets the class C Vps complex to coordinate autophagosome maturation and endocytic trafficking. Nat Cell Biol 2008; 10: 776–87.

Liang XH, Jackson S, Seaman M, Brown K, Kempkes B, Hibshoosh H, et al. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature 1999; 402: 672–6.

Qu X, Yu J, Bhagat G, Furuya N, Hibshoosh H, Troxel A, et al. Promotion of tumorigenesis by heterozygous disruption of the beclin 1 autophagy gene. J Clin Invest 2003; 112: 1809–20.

Yue Z, Jin S, Yang C, Levine AJ, Heintz N . Beclin 1, an autophagy gene essential for early embryonic development, is a haploinsuffcient tumor suppressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003; 100: 15077–82.

Aita VM, Liang XH, Murty VV, Pincus DL, Yu W, Cayanis E, et al. Cloning and genomic organization of beclin 1, a candidate tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 17q21. Genomics 1999; 59: 59–65.

Furuya N, Yu J, Byfield M, Pattingre S, Levine B . The evolutionarily conserved domain of Beclin 1 is required for Vps34 binding, autophagy and tumor-suppressor function. Autophagy 2005; 1: 46–52.

Ionov Y, Nowak N, Perucho M, Markowitz S, Cowell JK . Manipulation of nonsense mediated decay identifies gene mutations in colon cancer cells with microsatellite instability. Oncogene 2004; 23: 639–45.

Coppola D, Oliveri C, Sayegh Z, Boulware D, Takahashi Y, Pow-Sang J, et al. Bax-interacting factor-1 expression in prostate cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2008; 6: 117–21.

Coppola D, Khalil F, Eschrich SA, Boulware D, Yeatman T, Wang HG . Down-regulation of Bax-interacting factor-1 in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Cancer 2008; 113: 2665–70.

Kim SY, Oh YL, Kim KM, Jeong EG, Kim MS, Yoo NJ, et al. Decreased expression of Bax-interacting factor-1 (Bif-1) in invasive urinary bladder and gallbladder cancers. Pathology 2008; 40: 553–7.

Lee JW, Jeong EG, Soung YH, Nam SW, Lee JY, Yoo NJ, et al. Decreased expression of tumor suppressor Bax-interacting factor-1 (Bif-1), a Bax activator, in gastric carcinomas. Pathology 2006; 38: 312–5.

Green DR, Evan GI . A matter of life and death. Cancer Cell 2002; 1: 19–30.

Saeki K, Yuo A, Okuma E, Yazaki Y, Susin SA, Kroemer G, et al. Bcl-2 down-regulation causes autophagy in a caspase-independent manner in human leukemic HL60 cells. Cell Death Differ 2000; 7: 1263–9.

Pattingre S, Tassa A, Qu X, Garuti R, Liang XH, Mizushima N, et al. Bcl-2 antiapoptotic proteins inhibit Beclin 1-dependent autophagy. Cell 2005; 122: 927–39.

Maiuri MC, Le Toumelin G, Criollo A, Rain JC, Gautier F, Juin P, et al. Functional and physical interaction between Bcl-xL and a BH3-like domain in Beclin-1. EMBO J 2007; 26: 2527–39.

Oberstein A, Jeffrey PD, Shi Y . Crystal structure of the Bcl-XL-Beclin 1 peptide complex: Beclin 1 is a novel BH3-only protein. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 13123–32.

Wei Y, Pattingre S, Sinha S, Bassik M, Levine B . JNK1-mediated phosphorylation of Bcl-2 regulates starvation-induced autophagy. Mol Cell 2008; 30: 678–88.

Pattingre S, Bauvy C, Carpentier S, Levade T, Levine B, Codogno P . Role of JNK1-dependent Bcl-2 phosphorylation in ceramide-induced macroautophagy. J Biol Chem 2009; 284: 2719–28.

Zalckvar E, Berissi H, Eisenstein M, Kimchi A . Phosphorylation of Beclin 1 by DAP-kinase promotes autophagy by weakening its interactions with Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL. Autophagy 2009; 5: 720–2.

Maiuri MC, Criollo A, Tasdemir E, Vicencio JM, Tajeddine N, Hickman JA, et al. BH3-only proteins and BH3 mimetics induce autophagy by competitively disrupting the interaction between Beclin 1 and Bcl-2/Bcl-xL. Autophagy 2007; 3: 374–6.

Katso R, Okkenhaug K, Ahmadi K, White S, Timms J, Waterfield MD . Cellular function of phosphoinositide 3-kinases: implications for development, homeostasis, and cancer. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2001; 17: 615–75.

Engelman JA, Luo J, Cantley LC . The evolution of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases as regulators of growth and metabolism. Nat Rev Genet 2006; 7: 606–19.

Songyang Z, Shoelson SE, Chaudhuri M, Gish G, Pawson T, Haser WG, et al. SH2 domains recognize specific phosphopeptide sequences. Cell 1993; 72: 767–78.

Yu J, Wjasow C, Backer JM . Regulation of the p85/p110α phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase. Distinct roles for the N-terminal and C-terminal SH2 domains. J Biol Chem 1998; 273: 30199–203.

Arico S, Petiot A, Bauvy C, Dubbelhuis PF, Meijer AJ, Codogno P, et al. The tumor suppressor PTEN positively regulates macroautophagy by inhibiting the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B pathway. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 35243–46.

Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM . Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science 2005; 307: 1098–101.

Luo J, Manning BD, Cantley LC . Targeting the PI3K-Akt pathway in human cancer: rationale and promise. Cancer Cell 2003; 4: 257–62.

Cantley LC . The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science 2002; 296: 1655–7.

Shaw RJ, Cantley LC . Ras, PI(3)K and mTOR signaling controls tumor cell growth. Nature 2006; 441: 424–30.

Bader AG, Kang S, Zhao L, Vogt PK . Oncogenic PI3K deregulates transcription and translation. Nat Rev Cancer 2005; 5: 921–9.

Zhou BP, Liao Y, Xia W, Zou Y, Spohn B, Hung MC . HER-2/neu induces p53 ubiquitination via Akt-mediated MDM2 phosphorylation. Nat Cell Biol 2001; 3: 973–82.

Manning BD, Cantley LC . United at last: the tuberous sclerosis complex gene products connect the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway to mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signalling. Biochem Soc Trans 2003; 31: 573–8.

Hahn-Windgassen A, Nogueira V, Chen CC, Skeen JE, Sonenberg N, Hay N . Akt activates the mammalian target of rapamycin by regulating cellular ATP level and AMPK activity. J Biol Chem 2005; 280: 32081–9.

Engelman JA . Targeting PI3K signalling in cancer: opportunities, challenges and limitations. Nat Rev Cancer 2009; 9: 550–62.

Stommel JM, Kimmelman AC, Ying H, Nabioullin R, Ponugoti AH, Wiedemeyer R, et al. Coactivation of receptor tyrosine kinases affects the response of tumor cells to targeted therapies. Science 2007; 318: 287–90.

Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, Song Y, Hyland C, Park JO, et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science 2007; 316: 1039–43.

Guix M, Faber AC, Wang SE, Olivares MG, Song Y, Qu S, et al. Acquired resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer cells is mediated by loss of IGF-binding proteins. J Clin Invest 2008; 118: 2609–19.

Samuels Y, Velculescu VE . Oncogenic mutations of PIK3CA in human cancers. Cell Cycle 2004; 3: 1221–4.

Isakoff SJ, Engelman JA, Irie HY, Luo J, Brachmann SM, Pearline RV, et al. Breast cancer-associated PIK3CA mutations are oncogenic in mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res 2005; 65: 10992–1000.

Samuels Y, Diaz LA, Schmidt-Kittler O, Cummins JM, Delong L, Cheong I, et al. Mutant PIK3CA promotes cell growth and invasion of human cancer cells. Cancer Cell 2005; 7: 561–73.

Samuels Y, Ericson K . Oncogenic PI3K and its role in cancer. Curr Opin Oncol 2006; 18: 77–82.

Goodsell DS . The molecular perspective: the ras oncogene. Oncologist 1999; 4: 263–4.

Li J, Yen C, Liaw D, Podsypanina K, Bose S, Wang SI, et al. PTEN, a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase gene mutated in human brain, breast, and prostate cancer. Science 1997; 275: 1943–7.

Fingar DC, Blenis J . Target of rapamycin (TOR): An integrator of nutrient and growth factor signals and coordinator of cell growth and cell cycle progression. Oncogene 2004; 23: 3151–71.

Loewith R, Jacinto E, Wullschleger S, Lorberg A, Crespo JL, Bonenfant D, et al. Two TOR complexes, only one of which is rapamycin sensitive, have distinct roles in cell growth control. Mol Cell 2002; 10: 457–68.

Manning BD, Tee AR, Logsdon MN, Blenis J, Cantley LC . Identification of the tuberous sclerosis complex-2 tumor suppressor gene product tuberin as a target of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase / akt pathway. Mol Cell 2002; 10: 151–62.

Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, Wu J, Guan K L . TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signaling. Nat Cell Biol 2002; 4: 648–57.

Ma L, Chen Z, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Pandolfi PP . Phosphorylation and functional inactivation of TSC2 by Erk implications for tuberous sclerosis and cancer pathogenesis. Cell 2005; 121: 179–93.

Roux PP, Ballif BA, Anjum R, Gygi SP, Blenis J . Tumor-promoting phorbol esters and activated Ras inactivate the tuberous sclerosis tumor suppressor complex via p90 ribosomal S6 kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004; 101: 13489–94.

Stevens C, Lin Y, Harrison B, Burch L, Ridgway RA, Sansom O, et al. Peptide combinatorial libraries identify TSC2 as a death-associated protein kinase (DAPK) death domain-binding protein and reveal a stimulatory role for DAPK in mTORC1 signaling. J Biol Chem 2009; 284: 334–44.

Corradetti MN, Inoki K, Bardeesy N, DePinho RA, Guan KL . Regulation of the TSC pathway by LKB1: evidence of a molecular link between tuberous sclerosis complex and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Genes Dev 2004; 18: 1533–8.

Hoyer-Hansen M, Bastholm L, Szyniarowski P, Campanella M, Szabadkai G, Farkas T, et al. Control of macroautophagy by calcium, calmodulin-dependent kinase kinase-beta, and Bcl-2. Mol Cell 2007; 25: 193–205.

Herrero-Martin G, Hoyer-Hansen M, Garcia-Garcia C, Fumarola C, Farkas T, Lopez-Rivas A, et al. TAK1 activates AMPK-dependent cytoprotective autophagy in TRAIL-treated epithelial cells. EMBO J 2009; 28: 677–85.

Budanov AV, Karin M . p53 target genes sestrin1 and sestrin2 connect genotoxic stress and mTOR signaling. Cell 2008; 134: 451–60.

Kuroyanagi H, Yan J, Seki N, Yamanouchi Y, Suzuki Y, Takano T, et al. Human ULK1, a novel serine/threonine kinase related to UNC-51 kinase of Caenorhabditis elegans: cDNA cloning, expression, and chromosomal assignment. Genomics 1998; 51: 76–85.

Yan J, Kuroyanagi H, Tomemori T, Okazaki N, Asato K, Matsuda Y, et al. Mouse ULK2, a novel member of the UNC-51-like protein kinases: unique features of functional domains. Oncogene 1999; 18: 5850–9.

Chan EY, Kir S, Tooze SA . siRNA screening of the kinome identifies ULK1 as a multidomain modulator of autophagy. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 25464–74.

Hara T, Takamura A, Kishi C, Iemura S, Natsume T, Guan JL, et al. FIP200, a ULK-interacting protein, is required for autophagosome formation in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol 2008; 181: 497–510.

Chan EY, Longatti A, McKnight NC, Tooze SA . Kinase-inactivated ULK proteins inhibit autophagy via their conserved C-terminal domains using an Atg13-independent mechanism. Mol Cell Biol 2009; 29: 157–71.

Hosokawa N, Hara T, Kaizuka T, Kishi C, Takamura A, Miura Y, et al. Nutrient-dependent mTORC1 association with the ULK1-Atg13-FIP200 complex required for autophagy. Mol Biol Cell 2009; 20: 1981–91.

Jung CH, Jun CB, Ro SH, Kim YM, Otto NM, Cao J, et al. ULK-Atg13-FIP200 complexes mediate mTOR signaling to the autophagy machinery. Mol Biol Cell 2009; 20: 1992–2003.

Ganley IG, Lam du H, Wang J, Ding X, Chen S, iang X . ULK1.ATG13.FIP200 complex mediates mTOR signaling and is essential for autophagy. J Biol Chem 2009; 284: 12297–305.

Suzuki K, Kubota Y, Sekito T, Ohsumi Y . Hierarchy of Atg proteins in pre-autophagosomal structure organization. Genes Cells 2007; 12: 209–18.

Gingras AC, Raught B, Sonenberg N . Regulation of translation initiation by FRAP/mTOR. Genes Dev 2001; 15: 807–26.

Wu H, Zhu H, Liu DX, Niu TK, Ren X, Patel R, et al. Silencing of elongation factor-2 kinase potentiates the effect of 2-deoxy-D-glucose against human glioma cells through blunting of autophagy. Cancer Res 2009; 69: 2453–60.

Harada H, Andersen JS, Mann M, Terada N, Korsmeyer SJ . p70S6kinase signals cell survival as well as growth, inactivating the pro-apoptotic molecule BAD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001; 98: 9666–70.

Crighton D, Wilkinson S, O'Prey J, Syed N, Smith P, Harrison PR, et al. DRAM, a p53-induced modulator of autophagy, is critical for apoptosis. Cell 2006; 126: 121–34.

Maiuri MC, Malik SA, Morselli E, Kepp O, Criollo A, Mouchel PL, et al. Stimulation of autophagy by the p53 target gene Sestrin2. Cell Cycle 2009; 8: 1571–6.

Tasdemir E, Maiuri MC, Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Djavaheri-Mergny M, D'Amelio M, et al. Regulation of autophagy by cytoplasmic p53. Nat Cell Biol 2008; 10: 676–87.

Kroemer G, Jaattela M . Lysosomes and autophagy in cell death control. Nat Rev Cancer 2005; 5: 886–97.

Gozuacik D, Kimchi A . Autophagy as a cell death and tumor suppressor mechanism. Oncogene 2004; 23: 2891–906.

Kondo Y, Kanzawa T, Sawaya R, Kondo S . The role of autophagy in cancer development and response to therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2005; 5: 726–34.

Djavaheri-Mergny M, Botti J, Codogno P . Autophagy and autophagic cell death. In: Gewirtz DA, Holt SE, and Grant S (Eds). Apoptosis, Senescence, and Cancer. NJ: Humana Press; 2007. p 93–107.

Moretti L, Attia A, Kim KW, Lu B . Crosstalk between Bak/Bax and mTOR signaling regulates radiation-induced autophagy. Autophagy 2007; 3: 142–4.

Shimizu S, Kanaseki T, Mizushima N, Mizuta T, Arakawa-Kobayashi S, Thompson CB, et al. Role of Bcl-2 family proteins in a non-apoptotic programmed cell death dependent on autophagy genes. Nat Cell Biol 2004; 6: 1221–8.

Petiot A, Ogier-Denis E, Blommaart EF, Meijer AJ, Codogno P . Distinct classes of phosphatidylinositol 30-kinases are involved in signaling pathways that control macroautophagy in HT-29 cells. J Biol Chem 2000; 275: 992–8.

Takeuchi H, Kondo Y, Fujiwara K, Kanzawa T, Aoki H, Mills GB, et al. Synergistic augmentation of rapamycin-induced autophagy in malignant glioma cells by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B inhibitors. Cancer Res 2005; 65: 3336–46.

Morselli E, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Vicencio JM, Criollo A, Maiuri MC, et al. Anti- and pro-tumor functions of autophagy. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009; 1793: 1524–32.

Dalby KN, Tekedereli I, Lopez-Berestein G, Ozpolat B . Targeting the prodeath and prosurvival functions of autophagy as novel therapeutic strategies in cancer. Autophagy 2010; 6: 322–9.

Cheng Y, Qiu F, Ye YC, Guo ZM, Tashiro S, Onodera S, et al. Autophagy inhibits reactive oxygen species-mediated apoptosis via activating p38-nuclear factor-kappa B survival pathways in oridonin-treated murine fibrosarcoma L929 cells, FEBS J 2009; 276: 1291–306.

Cheng Y, Li H, Ren X, Niu T, Hait WN, Yang J . Cytoprotective Effect of the Elongation Factor-2 Kinase-Mediated Autophagy in Breast Cancer Cells Subjected to Growth Factor Inhibition. PLoS One 2010; 5: e9715.

Ertmer A, Huber V, Gilch S, Yoshimori T, Erfle V, Duyster J, et al. The anticancer drug imatinib induces cellular autophagy. Leukemia 2007; 21: 936–42.

Marks PA . Discovery and development of SAHA as an anticancer agent. Oncogene 2007; 26: 1351–6.

Younes A . Therapeutic activity of mTOR-inhibitors in mantle cell lymphoma: clues but no clear answers. Autophagy 2008; 4: 707–9.

Kim KW, Hwang M, Moretti L, Jaboin JJ, Cha YI, Lu B . Autophagy upregulation by inhibitors of caspase-3 and mTOR enhances radiotherapy in a mouse model of lung cancer. Autophagy 2008; 4: 659–68.

Miller WH, Schipper HM, Lee JS, Singer J, Waxman S . Mechanisms of action of arsenic trioxide. Cancer Res 2002; 62: 3893–903.

Kanzawa T, Zhang L, Xiao L, Germano IM, Kondo Y, Kondo S . Arsenic trioxide induces autophagic cell death in malignant glioma cells by upregulation of mitochondrial cell death protein BNIP3. Oncogene 2005; 24: 980–91.

Liu B, Cheng Y, Zhang B, Bian HJ, Bao JK . Polygonatum cyrtonema lectin induces apoptosis and autophagy in human melanoma A375 cells through a mitochondria-mediated ROS-p38-p53 pathway. Cancer Lett 2009; 275: 54–60.

Liu B, Cheng Y, Bian HJ, Bao JK . Molecular mechanisms of Polygonatum cyrtonema Lectin-induced apoptosis and autophagy in cancer cells. Autophagy 2009; 5: 253–5.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Ming-wei MIN for her critical review on this manuscript. We also thank Huai-long XU and Chun-yang LI for their assistance with this work. This review is partially based upon studies that were supported by grants from the Department of Defense BC050789 and from the National Cancer Institute CA 135038.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, B., Cheng, Y., Liu, Q. et al. Autophagic pathways as new targets for cancer drug development. Acta Pharmacol Sin 31, 1154–1164 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/aps.2010.118

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/aps.2010.118

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Induction of RAC1 protein translation and MKK7/JNK-dependent autophagy through dicer/miR-145/SOX2/miR-365a axis contributes to isorhapontigenin (ISO) inhibition of human bladder cancer invasion

Cell Death & Disease (2022)

-

Therapeutic effects of ginsenosides on breast cancer growth and metastasis

Archives of Pharmacal Research (2020)

-

Tetrandrine is a potent cell autophagy agonist via activated intracellular reactive oxygen species

Cell & Bioscience (2015)

-

Development of anticancer drugs based on the hallmarks of tumor cells

Tumor Biology (2014)

-

Autophagy, a novel target for chemotherapeutic intervention of thyroid cancer

Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology (2014)