Abstract

Although nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is associated with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS), studies on the direct relationship between NAFLD and snoring, an early symptom of OSAS, are limited. We evaluated whether snorers had higher risk of developing NAFLD. The study was performed using data of the Tongmei study (cross-sectional survey, 2,153 adults) and Kailuan study (ongoing prospective cohort, 19,587 adults). In both studies, NAFLD was diagnosed using ultrasound; snoring frequency was determined at baseline and classified as none, occasional (1 or 2 times/week), or habitual (≥3 times/week). Odds ratios (ORs) and hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals were estimated using logistic and Cox models, respectively. During 10 years’ follow-up in Kailuan, 4,576 individuals with new-onset NAFLD were identified at least twice. After adjusting confounders including physical activity, perceived salt intake, body mass index (BMI), and metabolic syndrome (MetS), multivariate-adjusted ORs and HRs for NAFLD comparing habitual snorers to non-snorers were 1.72 (1.25–2.37) and 1.29 (1.16–1.43), respectively. These associations were greater among lean participants (BMI < 24) and similar across other subgroups (sex, age, MetS, hypertension). Snoring was independently and positively associated with higher prevalence and incidence of NAFLD, indicating that habitual snoring is a useful predictor of NAFLD, particularly in lean individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is one of the most common chronic liver diseases worldwide1. NAFLD affects approximately 25% of the global population2, with more than 10% of cases occurring in lean people1. The prevalence of NAFLD ranges from 6.3% to 27.0% in Chinese adults3 and is increasing at a rate of 0.594% per year4. The rising prevalence of NAFLD, in conjunction with the pandemic of obesity and metabolic syndrome (MetS), represent an increasing global public health burden5.

Snoring is a common condition that is easily detected by co-sleepers. In a recent study among 10,139 people living in rural areas of northern China, 47.2% of men and 37.8% of women self-reported snoring6. Several meta-analyses have revealed that snoring is associated with higher risks of diabetes7, gestational diabetes mellitus, pregnancy-induced hypertension and preeclampsia8, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality9,10. Multiple randomized controlled trials have suggested a possible causal relationship between obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) and NAFLD2,11. Snoring is an early symptom of OSAS;12 however, to our knowledge, few studies have investigated the direct relationships between self-reported snoring and NAFLD. Thus, we conducted the first cross-sectional study and first independent validation cohort study designed to investigate whether individuals who self-reported snoring had a higher prevalence and incidence of NAFLD.

Low-to-moderate alcohol intake may have beneficial effects in patients with NAFLD13,14. Conversely, alcohol increases upper airway resistance and snoring15. To avoid potentially confounding effects associated with alcohol consumption, the present study focused on individuals who reported that they never drank beer, wine, or spirits.

Results

In the present study 2,153 participants (mean age 41.4 years) in the Tongmei study and 19,587 participants (mean age 52.7 years) in the Kailuan cohort were included (Fig. 1).

In Tongmei, the prevalence of NAFLD diagnosed via abdominal ultrasound was 29.6% (638/2,153), and those participants were more likely to be men, age ≥ 45 years, and to exhibit higher daily total energy intake, snoring, MetS and its components, higher body mass index (BMI), and elevated alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT). During the 10-year follow-up (follow-up rate 84.8%, 21,422/25,268; calculation is detailed in Supplementary Information), 4,576 patients with incident NAFLD were identified in Kailuan. Those patients were more likely to be women, age 45–65 years, not single, physical labourers, and non-smokers, and they were more likely to work on the surface, have a highest education level of high school, engage in sedentary behaviour for <4 hours per day, have moderate or high perceived salt intake, and exhibit habitual snoring, MetS and its components, higher BMI, and elevated ALT, C-reactive protein (CRP), and serum uric acid (SUA) (Tables 1 and S1).

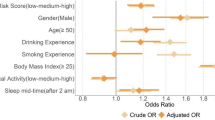

Compared with non-snorers, all snorers had higher prevalence and incidence of NAFLD, after adjusting for potential confounders; however, this was not the case for occasional snorers. Consistent results were obtained in sensitivity analyses (Table 2).

In Tongmei, habitual snoring was still associated with the prevalence of NAFLD in each stratum after stratifying by sex, age (<45 vs. ≥45 years), workplace (underground vs. surface), occupation type, BMI, MetS, arterial hypertension, and waist circumference (WC); however, this was only significant in participants who did not have simple overweight or hyperglycaemia, and those who had hypertriglyceridemia or low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C). Obesity, BMI, and hypertriglyceridemia modified the effects of habitual snoring on NAFLD (Fig. 2, Tables 3 and S2). The association between habitual snoring and NAFLD prevalence was stronger among lean participants (BMI < 24 or those with normal BMI and WC), and patients with hypertriglyceridemia.

Stratified odds ratio (OR) (95% confidence interval (CI)) of snoring on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease according to (a) age, sex, obesity, body mass index(BMI) and metabolic syndrome (MetS), and (b) MetS components in the Tongmei population, adjusted for age (<45 or ≥45 years), sex, marital status (single, married, divorced/widowed/separated), education (illiterate/primary, junior high school, senior high school or college, bachelor’s degree or higher), income (≤4000, >4000–6000, >6000 RMB), workplace (underground/surface), occupation type (mental labour/light physical labour/heavy physical labour), current tobacco smoking (yes, no), perceived salt intake (low, medium, high), degree of International physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ) (low, moderate, high), degree of sedentary behaviour (low, moderate, high), total energy intake per day (low, moderate, high), elevated serum liver enzymes (no/yes), obesity (normal, central, overweight, both), and MetS (no/yes). Yellow indicates habitual snorers compared with non-snorers; blue indicates occasional snorers compared with non-snorers. Significant P values are shown for interaction on a multiplicative scale.

In Kailuan, habitual snoring was still associated with the incidence of NAFLD in each stratum according to sex, age, occupation type, BMI, MetS, arterial hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and HDL-C; this was only significant in participants who were surface workers, did not have simple central obesity, or hyperglycaemia, and who had normal WC. Obesity, BMI, and hyperglycaemia modified the effects of habitual snoring on NAFLD (Fig. 3, Table 4 and S3). The association between habitual snoring and NAFLD risk was greater among lean participants (BMI < 24 or those with normal BMI and WC), and those who did not exhibit hyperglycaemia.

Stratified relative risk (RR) (95% confidence interval (CI)) of snoring on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease according to (a) age, sex, obesity, body mass index (BMI) and metabolic syndrome (MetS), and (b) MetS components in the Kailuan cohort, adjusted for age (<45, 45–<55, 55–<65, ≥65 years), sex, marital status (single, married, divorced/widowed/separated), education (illiterate/primary, junior high school, senior high school, college or higher), income (<600, 600–800, 800–1000, >1000 RMB), workplace (underground/surface), occupation type (mental labour/physical labour), current tobacco smoking (yes, no), perceived salt intake (low, medium, high), physical activity (no, occasional, always), sedentary duration (<4, 4–8, >8 hours per day), elevated ALT (>40 U/L), obesity (normal, simple central, simple overweight, both), elevated SUA (>357 μmol/ L for women and >420 μmol/ L for men), CRP (<1, 1–3, >3 mg/L), and MetS (no/yes). Yellow indicates habitual snorers compared with non-snorers; blue indicates occasional snorers compared with non-snorers. Significant P values are shown for interaction on a multiplicative scale.

Interestingly, occasional snoring was still not associated with NAFLD after stratification in either population, except in participants age <45 years, and those who were mental (versus manual) labourers in Kailuan. Heterogeneous effects were detected after stratifying by age and occupation type in Kailuan (Figs. 2 and 3; Tables 3, 4, S2 and S3). The association between occasional snoring and NAFLD risk was stronger among young participants (age < 45 years), and mental labourers.

Discussion

In this study, we established an association of self-reported snoring with NAFLD in a sampling-based cross-sectional population, and we validated this association in an independent large prospective cohort. Our findings indicated that self-reported snoring was significantly associated with a higher risk of subsequently developing NAFLD during a 10-year follow-up. These associations were independent of known risk factors for NAFLD such as obesity (defined according to BMI and WC in the present study), MetS and its components, age, smoking, sedentary behaviour, physical inactivity, elevated CRP, elevated SUA, and high salt intake1,16,17. To our knowledge the present study is the first to provide evidence of a direct association between snoring and an increased risk of NAFLD.

The association between habitual snoring and NAFLD was greater among lean participants (BMI < 24 or those with normal BMI and WC) in both populations. These results suggest that the presence of elevated BMI (or elevated BMI and WC) may buffer the effects of snoring on NAFLD. This is concordant with previous studies in which strong associations were found between obesity and increased prevalence and development of snoring15.

In stratification analyses of two independent populations, habitual snoring was still significantly associated with increased prevalence and incidence of NAFLD in each stratum after stratifying by sex, age, MetS, arterial hypertension, and BMI in both analyses. Interestingly, the risk of NAFLD was significantly associated with habitual snoring in participants who did not have hyperglycaemia, and had normal WC, in both analyses; however, this was not the case in workers who exhibited hyperglycaemia in both analyses; and had elevated WC in the cohort analyses. These results suggest that hyperglycaemia and elevated WC may be stronger risk factors for the development of NAFLD than habitual snoring.

High BMI, elevated WC, the presence of diabetes, and the presence of MetS are well-known primary risk factors for the development of NAFLD that are usually concurrent with NAFLD1. Lean NAFLD is also not uncommon; however, this represents a clinical challenge because the diagnosis of NAFLD may be delayed or ignored in such cases owing to an absence of the aforementioned common comorbidities18. Notably, the results of the present study suggest that habitual snoring may be a useful early indicator of NAFLD even in the absence of common comorbidities.

Some inconsistent results pertaining to simple central obesity and simple overweight were obtained in the two study populations. This may be owing to different distributions of body types among these populations. In Tongmei, similar proportions of participants had simple central obesity (12.0%) and simple overweight (12.7%), and the largest proportion of participants (43.1%) exhibited both forms of obesity. In Kailuan, 27.3% of participants had simple overweight and only 7.4% had simple central obesity, and the largest proportion of participants (45.5%) exhibited normal BMI and WC. Furthermore, compared with non-snorers who had normal BMI and WC, ORs and HRs of NAFLD in participants with elevated BMI and/or elevated WC were dramatically increased. This confirmed that controlling weight and WC are very important in the management of NAFLD.

The proportions of NAFLD in men and women were inconsistent in the present two populations; this conflict is common, as previously reported19. Interestingly, female non-snorers and male snorers had similar risks of NAFLD in both populations. In stratified analyses, however, habitual snoring was consistently significantly associated with increased risk of NAFLD among men and women. In a recently reported cross-sectional study, self-reported snoring status was compared with polysomnography results; in that study women tended to under-report their snoring and men tended to over-report snoring20. This apparent sex difference in self-reporting may contribute to the comparatively lower risk in men than in women.

Snoring is an early symptom of OSAS12, and OSAS has been incorporated in two prediction models of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in morbidly obese patients, to optimize the selection of patients for liver biopsy21. The prevalence of OSAS in the general population is relatively low30, however, and the diagnosis of OSAS relies on polysomnography. Habitual snoring is common in the general population and can be easily detected by co-sleepers. Therefore, we speculate that self-reported habitual snoring can be incorporated in prediction models of NAFLD. This association was confirmed in the present cohort study, but needs to be validated in more extensive populations.

The mechanisms involved in the association between snoring and NAFLD have not been elucidated, but several explanations for the causal relationship between OSAS and NAFLD have been suggested22,23. Sleep-disordered breathing leads to chronic intermittent hypoxia, which may cause liver injury, lipid deposition, inflammation, and fibrogenesis via activation of hypoxia inducible factor, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells, or the induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress, tissue inflammation, and insulin resistance22,23. OSAS increases the number of micro-arousals, the accumulation of which causes sleep fragmentation and reduces its restorative value24,25. In a randomized controlled trial, it was concluded that the sound of snoring probably increased the number of micro-arousals26. Collectively, these potential mechanisms may constitute the pathophysiological basis of the association between snoring and increased risk of NAFLD.

Liver biopsy is the gold standard for NAFLD diagnosis but biopsy is not feasible in a large population-based study. Ultrasound is a widely accessible imaging technique for the detection of fatty liver in clinical and population settings owing to its relatively low cost and verified safety27. To minimize the effects of misclassification via ultrasound in the present study, two separate analyses were conducted. In one analysis, at least two positive determinations via ultrasound were required to qualify a participant as a new NAFLD case16 in a separate analysis, an alternative definition of “at least one positive report” was used. Similar results were obtained using either definition.

In the present study, the presence and frequency of snoring was based on self-reporting that was undoubtedly influenced by input from participants’ families, and this may have resulted in under- or over-reporting15,20. Notably, snoring can be detected by co-sleepers; detection, quantification, and data acquisition using more objective methods was beyond the scope of the present study, which used data derived from very large population-based cohorts. With regard to future studies, it has been reported that low-cost no-contact or contact microphones that do not affect sleep quality are effective, and acoustic analysis of snoring is now considered a highly accurate diagnostic tool for OSAS versus polysomnography28. Further studies using such methods are encouraged, to confirm the findings of the present study. Effective treatments are also available for snoring, such as low-level continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), oropharyngeal exercises, oral appliance therapy, and the use of specific types of pillows29,30,31,32,33. A recent review indicated that CPAP, the first-line treatment for OSAS, may be beneficial with regard to liver disease in people with OSAS, independent of metabolic risk factors34.

The two populations included in the current study were occupation-based, so caution should be used in extrapolating the results to more general populations. Compared with population-based studies, the common issue of an unbalanced ratio of men and women existed; because the majority of coal mine staff are men. Interestingly, the sex ratio in Kailuan was close to that in the general population, which was at least partly because alcohol drinkers were excluded from the analysis and the proportion of male drinkers was larger than that of female drinkers. Furthermore, interaction analysis consistently indicated that there were no significant differences in ORs or HRs between men and women.

Detailed dietary information and a history of OSAS at baseline were obtained in Tongmei, and high total energy intake was a risk factor for NAFLD in a crude model. Comparable dietary information and OSAS history were not obtained in Kailuan, however, so the two populations could not be compared in this regard. Moreover, individuals with genotype 3 HCV infection were not excluded in this study because only a history of HCV infection was collected in Tongmei and Kailuan; genotype testing was not feasible in these two large population-based studies. However, the prevalence of genotype 3 HCV infection is low in Chinese populations11,35. Lastly, although several potential confounders were adjusted in the models, because the current investigation was an observational study, the present results may have been affected by additional independent NAFLD risk factors and snoring risk factors that could not be incorporated into the analysis owing to unavailability, such as myopenia measured via body composition, genetic susceptibility genes, neck circumference, or cranio-facial differences; in addition, anatomical aspects such as single or multi-level obstruction, muscle tonus, and length of the upper airway may influence the intensity of snoring1,15,36.

Conclusion

Snoring is a common condition that may be associated with the prevalence and 10-year incidence of NAFLD. Habitual snoring may be particularly useful as a low-cost, non-invasive, and convenient predictor of NAFLD, especially in individuals who do not exhibit common comorbidities. Further research investigating the underlying mechanisms involved in the association between snoring and NAFLD is warranted, as are prospective studies investigating the effects of attenuating snoring symptoms on NAFLD.

Methods

Study population

The Tongmei study was a cross-sectional health survey of staff working for Datong Coal Mine Group37,38 (Datong, China). Using two-stage cluster stratified sampling, 4,341 employees (84.2% men, age 18–65 years) were recruited from July 2013 to December 2013. The Kailuan study, an ongoing prospective cohort study of coal mine staff working for the Kailuan Group16,39 (Tangshan, China) from June 2006 to December 2017, was also used for validation. In 2006 and 2007 (baseline), 101,510 employees and retirees (80.3% men, age 18–97 years) were recruited in 11 hospitals, and then followed biennially. The designs and methods of the Tongmei and Kailuan studies have been detailed elsewhere16,37,38,39.

Both the Tongmei study and Kailuan study consisted of face-to-face interviews, clinical examinations, and acquisition of laboratory data. These studies were conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocols were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committees of Shanxi Medical University and Kailuan General Hospital, respectively. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants before data collection.

Exclusion criteria included (1) self-reported alcohol consumption, or missing alcohol consumption history data; (2) liver cirrhosis; (3) presence of diseases such as OSAS, thyroid disease, or cancer; (4) taking a drug that could potentially affect snoring or NAFLD, or long-term use of sedative-hypnotic drugs; and (5) missing ultrasound data or data pertaining to other covariates. In the Kailuan study, we additionally excluded (6) participants with NAFLD at baseline; (7) participants without follow-up data; (8) participants who self-reported drinking during follow-up; and (9) participants with liver cirrhosis during follow-up.

Data collection and definitions

Blood pressure measurement, anthropometry, overnight fasting blood specimen collection, physical examination, and abdominal ultrasound were performed in the morning by trained and certified nurses, physicians, or experienced radiologists who were blinded to the laboratory findings, in accordance with standard protocols and techniques40. In face-to-face interviews, each participant was asked about demographics, lifestyle, nutrition, and physical activity, and participants’ medical history was collected via self-administered questionnaires.

In the Tongmei study, physical activity level and sedentary behaviour were assessed using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)41, and a validated semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire was used to obtain data reflecting dietary intake in the past year42. Notably, no nutrition survey was involved in the Kailuan baseline survey. Laboratory staff assessed blood biochemical indexes and blood glucose using automatic analysers (Tongmei: SIEMENS ADVIA 1800 at the General Hospital of Datong Coal Mining Group; Kailuan: Hitachi 747 at the Central Laboratory of the Kailuan General Hospital). C-reactive protein and serum uric acid were only tested in Kailuan. Alcohol consumption was ascertained using a structured questionnaire, including the consumption of beer, wine, and spirits.

Definitions and calculations

NAFLD was diagnosed by experienced radiologists via abdominal ultrasonography (Tongmei: portable MyLab 30CV, Biosound Esaote; Kailuan: HD-15, Philips) at recruitment in both studies; NAFLD was monitored biennially from 2008–2017 in Kailuan. The criteria for determination of NAFLD suggested by the Chinese Liver Disease Association were used1 as previously described16. Alternative causes, such as alcohol consumption and systemic diseases or medications before a diagnosis of NAFLD were ruled out according to the history of drinking, drug use, and diseases. Owing to the relatively low sensitivity and specificity of ultrasonography for detecting moderate or severe liver steatosis compared with histology16,27, NAFLD was defined as positive liver steatosis determined via ultrasonography, and incident NAFLD was defined as patients without NAFLD at baseline and with at least two reports of positive liver steatosis at any time from 2008 to 201716. For cases of incident NAFLD, person-time of follow-up was calculated from the date of the 2006 survey (baseline) to the date of the first NAFLD diagnosis; for the remainder, person-time of follow-up was calculated from the date of baseline to the date of the last follow-up.

Snoring status was self-reported by participants, and was often ascertained with the assistance of family members, with regard to the question “Have you ever snored while asleep?” In both studies, there were three response choices for that question: “never”, “occasionally (1 or 2 times/week)”, and “habitually (≥3 times/week)”.

MetS was diagnosed with the presence of any three of the following five factors1: (1) elevated waist circumference: waist circumference >90 cm in men and >85 cm in women; (2) arterial hypertension: arterial blood pressure ≥130/85 mmHg or on antihypertensive therapy; (3) hypertriglyceridemia: fasting serum triglycerides ≥1.7 mmol/L or on lipid-lowering medication; (4) low HDL-C: fasting serum HDL-C < 1.0 mmol/L in men or <1.3 mmol/L in women; and (5) hyperglycaemia: fasting serum glucose ≥5.6 mmol/L or a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Obesity was defined based on both BMI and WC, and included four categories: normal (normal BMI and WC), simple central obesity (normal BMI and elevated WC), simple overweight (elevated BMI and normal WC), and both forms of obesity (elevated BMI and WC).

Physical activity and sedentary behaviour were defined as low, moderate, or high in accordance with IPAQ guidelines41. Total energy intake per day was calculated based on China Food Composition30, and categorized according to tertiles. In the Kailuan study, physical activity and sedentary behaviour were respectively evaluated based on answers to questions pertaining to the frequency of physical activity and duration of sedentary behaviour. Salt intake was self-reported as low, medium, or high as described previously16. Elevated serum liver enzymes was defined as any among ALT, AST, and GGT higher than the upper normal limit (40, 45, and 58 U/L, respectively). Elevated SUA was defined as >420 μmol/L in men and >357 μmol/L in women. Current smokers were those who had smoked at least one cigarette per month during the past year.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Characteristics of the study samples were summarized as frequencies and percentages according to NAFLD status and study. Logistic regression was used in cross-sectional analyses and Cox regression was used in cohort analyses, to investigate associations between snoring and NAFLD. Crude odds ratios (ORs) or crude hazard ratios (HRs) together with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated via univariate regression. Adjusted ORs or adjusted HRs and corresponding 95% CIs were also calculated in multivariate regression, controlling for potential confounders. In view of the different covariates collected in Tongmei and Kailuan, different covariates were used. Lastly, adjustments were made in the two populations for age, sex, marital status, education, income, workplace, current tobacco smoking, BMI, physical activity, sedentary behaviour, perceived salt intake, and MetS. Additional adjustments for daily total energy intake and elevated serum liver enzymes were applied to data derived from the Tongmei study, and additional adjustments for elevated ALT, elevated SUA, and CRP were applied to data derived from the Kailuan study.

We investigated interactions on additive and multiplicative scales between snoring and sex, age, workplace, obesity, BMI, and MetS and its components, which may have modified the associations between snoring and NAFLD. Additive interaction was evaluated via relative excess risk owing to interaction (RERI) and the corresponding 95% CI43.

Sensitivity analysis

Modified Poisson models were used to test the sensitivity of the results in cross-sectional analyses44. A broader definition of NAFLD was used to test the sensitivity of the results in cohort analyses, where incident NAFLD cases were defined as those without NAFLD at baseline and with at least one positive ultrasonography result during 2008–2017.

References

Fan, J. G., Wei, L. & Zhuang, H. Guidelines of prevention and treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (2018, China). J. Dig. Dis. 20, 163–173, https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-2980.12685 (2019).

Younossi, Z. M. et al. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 64, 73–84, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.28431 (2016).

Wang, F. S., Fan, J. G., Zhang, Z., Gao, B. & Wang, H. Y. The global burden of liver disease: the major impact of China. Hepatology 60, 2099–2108, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.27406 (2014).

Zhu, J. Z. et al. Prevalence of fatty liver disease and the economy in China: A systematic review. World J. Gastroenterol. 21, 5695–5706, https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i18.5695 (2015).

Loomba, R. & Sanyal, A. J. The global NAFLD epidemic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 10, 686–690, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2013.171 (2013).

Zhang, N. et al. Self-Reported Snoring Is Associated with Dyslipidemia, High Total Cholesterol, and High Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol in Obesity: A Cross-Sectional Study from a Rural Area of China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14, 1–10(86), https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14010086 (2017).

Xiong, X., Zhong, A., Xu, H. & Wang, C. Association between Self-Reported Habitual Snoring and Diabetes Mellitus: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Diabetes Res. 2016, 1958981, https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/1958981 (2016).

Li, L., Zhao, K., Hua, J. & Li, S. Association between Sleep-Disordered Breathing during Pregnancy and Maternal and Fetal Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Neurol, 1-9(91), https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2018.00091 (2018).

Li, M., Li, K., Zhang, X. W., Hou, W. S. & Tang, Z. Y. Habitual snoring and risk of stroke: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int. J. Cardiol. 185, 46–49, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.03.112 (2015).

Li, D., Liu, D., Wang, X. & He, D. Self-reported habitual snoring and risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality. Atherosclerosis 235, 189–195, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.04.031 (2014).

Chen, Y. et al. Hepatitis C virus genotypes and subtypes circulating in Mainland China. Emerg. microbes Infect. 6, 1–7 (2017).

Lam, J. C., Sharma, S. K. & Lam, B. Obstructive sleep apnoea: definitions, epidemiology & natural history. Indian. J. Med. Res. 131, 165–170 (2010).

Farrell, G. C., Wong, V. W. & Chitturi, S. NAFLD in Asia–as common and important as in the West. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 10, 307–318, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2013.34 (2013).

Chalasani, N. et al. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Gastroenterological Association. Hepatology 55, 2005–2023, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.25762 (2012).

Deary, V., Ellis, J. G., Wilson, J. A., Coulter, C. & Barclay, N. L. Simple snoring: not quite so simple after all? Sleep. Med. Rev. 18, 453–462, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2014.04.006 (2014).

Shen, X. et al. Prospective study of perceived dietary salt intake and the risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of human nutrition and dietetics: the official journal of the British Dietetic Association, https://doi.org/10.1111/jhn.12674 (2019).

Zhu, F. et al. Predictive value of C-reactive protein in emerging non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing. Za Zhi 24, 575–579, https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-3418.2016.08.004 (2016).

Sookoian, S. & Pirola, C. J. Systematic review with meta-analysis: risk factors for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease suggest a shared altered metabolic and cardiovascular profile between lean and obese patients. Alimentary pharmacology therapeutics 46, 85–95, https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.14112 (2017).

Sayiner, M., Koenig, A., Henry, L. & Younossi, Z. M. Epidemiology of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis in the United States and the Rest of the World. Clin. liver Dis. 20, 205–214, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cld.2015.10.001 (2016).

Westreich, R. et al. The Presence of Snoring as Well as its Intensity Is Underreported by Women. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 15, 471–476, https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.7678 (2019).

Vilar-Gomez, E. & Chalasani, N. Non-invasive assessment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Clinical prediction rules and blood-based biomarkers. J. Hepatol. 68, 305–315, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.11.013 (2018).

Li, M., Li, X. & Lu, Y. Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome and Metabolic Diseases. Endocrinology 159, 2670–2675, https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2018-00248 (2018).

Lefere, S. et al. Hypoxia-regulated mechanisms in the pathogenesis of obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 73, 3419–3431, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-016-2222-1 (2016).

Leineweber, C., Kecklund, G., Akerstedt, T., Janszky, I. & Orth-Gomer, K. Snoring and the metabolic syndrome in women. Sleep. Med. 4, 531–536 (2003).

Roehrs, T., Zorick, F., Wittig, R., Conway, W. & Roth, T. Predictors of objective level of daytime sleepiness in patients with sleep-related breathing disorders. Chest 95, 1202–1206, https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.95.6.1202 (1989).

Chirakalwasan, N., Ruzicka, D. L., Burns, J. W. & Chervin, R. D. Do snoring sounds arouse the snorer? Sleep 36, 565–571, https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.2546 (2013).

Hernaez, R. et al. Diagnostic accuracy and reliability of ultrasonography for the detection of fatty liver: a meta-analysis. Hepatology 54, 1082–1090, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.24452 (2011).

Jin, H. et al. Acoustic Analysis of Snoring in the Diagnosis of Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome: A Call for More Rigorous Studies. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 11, 765–771, https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.4856 (2015).

Guzman, M. A. et al. The Efficacy of Low-Level Continuous Positive Airway Pressure for the Treatment of Snoring. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 13, 703–711, https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.6588 (2017).

Cazan, D., Mehrmann, U., Wenzel, A. & Maurer, J. T. The effect on snoring of using a pillow to change the head position. Sleep. Breath. 21, 615–621, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-017-1461-1 (2017).

Ramar, K. et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Snoring with Oral Appliance Therapy: An Update for 2015. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 11, 773–827, https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.4858 (2015).

Ieto, V. et al. Effects of Oropharyngeal Exercises on Snoring: A Randomized Trial. Chest 148, 683–691, https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.14-2953 (2015).

Al-Hussaini, A. & Berry, S. An evidence-based approach to the management of snoring in adults. Clin. Otolaryngol. 40, 79–85, https://doi.org/10.1111/coa.12341 (2015).

Liu, X., Miao, Y., Wu, F., Du, T. & Zhang, Q. Effect of CPAP therapy on liver disease in patients with OSA: a review. Sleep. Breath. 22, 963–972, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-018-1622-x (2018).

Cui, Y. & Jia, J. Update on epidemiology of hepatitis B and C in C hina. J. gastroenterology hepatology 28, 7–10 (2013).

De Meyer, M. M. D., Jacquet, W., Vanderveken, O. M. & Marks, L. A. M. Systematic review of the different aspects of primary snoring. Sleep. Med. Rev. 45, 88–94, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2019.03.001 (2019).

Ma, K. L. et al. Sleep quality mediating the association of personality traits and quality of life among underground workers and surface workers of Chinese coal mine: A multi-group SEM with latent response variable mediation analysis. Psychiatry Res, 196-205, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.006 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. Additive interaction of snoring and body mass index on the prevalence of metabolic syndrome among Chinese coal mine employees: a cross-sectional study. BMC Endocr Disord 19, 1-9(28), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-019-0352-9 (2019).

Huang, S. et al. Longitudinal study of alcohol consumption and HDL concentrations: a community-based study. The. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 105, 905–912, https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.116.144832 (2017).

Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organ. Tech. Rep. Ser. 854, 1–452 (1995).

Fan, M., Lyu, J. & He, P. Chinese guidelines for data processing and analysis concerning the International Physical Activity Questionnaire. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing. Xue Za Zhi 35, 961–964 (2014).

Li, L. M. et al. A description on the Chinese national nutrition and health survey in 2002. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing. Xue Za Zhi 26, 478–484 (2005).

Knol, M. J. & VanderWeele, T. J. Recommendations for presenting analyses of effect modification and interaction. Int. J. Epidemiol. 41, 514–520, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyr218 (2012).

Spiegelman, D., Hertzmark, E. & Easy, S. A. S. calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am. J. Epidemiol. 162, 199–200, https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwi188 (2005).

Acknowledgements

Authors appreciate all participants in our study for their time and participation. Authors would also like to acknowledge all interviewers and relevant management staff for survey data collection work and the support of Graduate Student Innovation Center in Shanxi Province of China, Datong Coal Mine Group and General Hospital of Datong Coal Mining Group. The study is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (item number: 81872715).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design, Hui Wang, Jianjun Huang, Shouling Wu and Tong Wang; Data acquisition, Chenming Sun, Shuohua Chen and Qian Gao; Formal analysis, Hui Wang; Methodology, Hui Wang and Hongwei Sun; Validation, Qian Gao and Simin He; Writing – original draft, Hui Wang; Writing – review & editing, Qian Gao, Yanping Bao, Lingxian Meng, Jie Liang, Liying Cao, Wei Huang, Yanmin Zhang and Tong Wang. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, H., Gao, Q., He, S. et al. Self-reported snoring is associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Sci Rep 10, 9267 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-66208-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-66208-1

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.