Abstract

Defect-based quantum systems in wide bandgap semiconductors are strong candidates for scalable quantum-information technologies. However, these systems are often complicated by charge-state instabilities and interference by phonons, which can diminish spin-initialization fidelities and limit room-temperature operation. Here, we identify a pathway around these drawbacks by showing that an engineered quantum well can stabilize the charge state of a qubit. Using density-functional theory and experimental synchrotron X-ray diffraction studies, we construct a model for previously unattributed point defect centers in silicon carbide as a near-stacking fault axial divacancy and show how this model explains these defects’ robustness against photoionization and room temperature stability. These results provide a materials-based solution to the optical instability of color centers in semiconductors, paving the way for the development of robust single-photon sources and spin qubits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

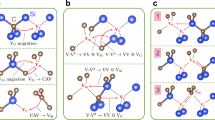

Solid-state defects have emerged as candidate systems for quantum-information technologies related to nanoscale sensing and communication1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11, building on the ability to engineer their crystallographic environments. The sensitivity and robustness of these systems are strongly dictated by their local environment influencing the charge state stability throughout their optical initialization and read-out cycles and spin coherence times12,13. However, optical manipulation regularly results in undesired ionization processes, fluctuating the defect’s charge state and functionality (see Fig. 1a–c)14,15,16,17,18,19. These undesired non-radiative pathways are a recurring challenge with most point defect qubits, including the nitrogen-vacancy (NV) center in diamond14,15,20,21, the divacancy (VV) in silicon carbide (SiC)7,8,16,17,18,22, and the silicon vacancy (VSi) in SiC9,16,23.

a A bright state of a color center under optical excitation. b These incident photons may ionize the defect and turn it into a dark state while also, c, does not have sufficient energy to repopulate the bright state. d In a quantum well, however, the excitation laser can successfully re-pump the bright state. e Band structure of a defective 4H-SiC including a stacking fault. Red curves depict bulk-like conduction and valence band states in the basal plane of the hexagonal Brillouin zone. Purple curves show the stacking fault states that localized in c direction and dispersive in the basal plane.

Beside the already identified divacancy configurations (PL1-4 in 4H-SiC and QL1-6 in 6H-SiC)7,24,25,26, related color centers with unknown atomic configurations (PL5-7 in 4H-SiC and QL7-9 in 6H-SiC) have been recently reported7,16,18,24,27. Unlike to the regular divacancy defects, the additional color centers demonstrate robustness against photoionization effects16 and optical spin contrast persisting up to room temperature7,24,27. Identification and characterization of these stable emitters may be a key to find material-based solutions for stabilizing color centers against optical pumping.

Here, we demonstrate that a quantum well, defined by a Frank-type stacking fault28, stabilizes divacancies in their neutral charge-state. We provide complementary experimental evidence that such crystallographic configurations exist in commercially available SiC crystal substrates and associate the previously unattributed PL5-PL7 defects in 4H-SiC7,24 to near-stacking fault divacancies predicted to form within the well’s vicinity. Based on these findings, we outline an engineerable method to circumvent undesired ionization effects by manipulating the host material’s local band structure. Local change in the crystal lattice stacking order creates a quantum well that lowers the ionization energy of a point defect’s dark state (see Fig. 1d). This energy reduction, in turn, enables new optoelectronic transitions, allowing incident illumination to preferentially repopulate the desired point defect’s bright state (see Fig. 1d). The approach highlighted in this paper provides a materials-based solution to the optical instability problem of color centers in a variety of solid-state systems paving the way towards robust, defect-based single-photon emitters and spin qubits.

Results

Numerical calculations

It has been suggested that quantum well structures in wide bandgap semiconductors allow for color center defects with properties distinct from their homologues in unperturbed bulk-like crystal environments29. If true, these local transition energy disturbances should allow for the reversal of undesired laser-induced bright-to-dark charge state effects by opening new dark-state ionization pathways. To study this, we model 4H-SiC (see Fig. 2a) as a prototypical host material with known crystallographically defined quantum wells30,31,32,33 and color centers7,9,34. In this context, we investigate stacking faults (i.e. polytypic inclusions in 4H-SiC) as an intrinsic quantum well forming mechanism35,36,37, and the effects that these structures have on divacancy defect (two adjacent empty atomic sites) color centers in their vicinity.

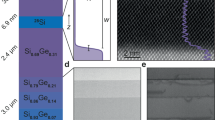

a–c show the primitive cells, the stacking sequences, and the possible divacancy nonequivalent configurations in 4H, 6H, and 3C-SiC, respectively. Here, h and k stand for hexagonal-like and cubic-like environments of Si or C sites, respectively, and the double letters for the vacancy sites of the VSi–VC divacancy pair defect configurations. d A single stacking fault in a cubic-like stacking order in 4H-SiC. The close vicinity of the stacking fault resembles the 6H stacking and thus it gives rise to 6H-like additional divacancy configurations in 4H-SiC. The k2k2-ssf configuration is assigned to PL6 room-temperature qubits.

The insertion of a single cubic SiC double layer (see Fig. 2c) into the 4H-SiC primitive cell results in a Frank-type stacking fault (a 1FSF(3,2) fault in the Zhdanov notation)28 as shown in Fig. 2d. The resulting stacking irregularity is seen to be indistinguishable from a polytypic 6H-SiC (see Fig. 2b) inclusion in a 4H-SiC crystal37,38. It has been shown that such stacking faults form quantum-well-like states that have been observed through photoluminescence (PL)35,36,37 measurements in which the 6H in 4H polytypic inclusion was typically identified using the 482 nm PL-emission line37.

Building on these observations, we calculate the change in 4H-SiC band structure with a 6H polytypic inclusion (see Fig. 1e). This stacking fault gives rise to energy states below the 4H-SiC conduction band minimum, effectively lowering the band-gap value (Eg) by ~0.24 eV in its vicinity (up to ~15 Å from the stacking fault). This calculation does not account for electron–hole interactions that may further reduce the local Eg of the defective 4H-SiC host. Nevertheless, these results illustrate that even a single stacking fault can significantly change the local Eg structure. This local change in accessible energy levels, and the changes in photoionization energies that occur as a result, influence the charge state stability of local point defects states16.

The effect of this quantum well structure on the different possible 4H-SiC divacancy sites was investigated. There are two inequivalent sites for both Si and C in the primitive cell of 4H-SiC (see Fig. 2a). Consequently, point defects have multiple nonequivalent configurations that differ primarily in the makeup of their second and further neighbor shells. The configurations of a single site defect in the 4H polytype are marked by h or k, referring to a more hexagonal or cubic-like environment, respectively (see Fig. 2a–d). This distinction leads to divacancy defects having altogether four possible configurations in 4H-SiC: hh, kk, hk, and kh. Additionally, depending on whether the VSi–VC axis is parallel or inclined (at ~109.5° angle) to the c-axis, the divacancies can exhibit either high (C3v) or low (C1h) symmetry. Hereinafter, we refer to these configurations as axial and basal plane divacancies, respectively. In recent years, each of these photoluminescent VV configurations have been assigned to various qubits in 4H-SiC7,25,39.

In our calculations, we considered two sets of divacancy configurations within a single model: (a) divacancies in the near-stacking fault region, up to 5 Å away from the stacking fault; and (b) divacancy configurations in a more bulk-like environment, at least 14 Å away from the stacking fault. The near-stacking fault and bulk-like configurations are denoted with a suffix –ssf (single stacking fault) and −4H, respectively (see Fig. 2d) with the prefix representing silicon and carbon vacancies in both hexagonal-like and cubic-like environment. In the context of the stacking fault, we distinguish three cubic-like and two hexagonal-like lattice sites: k1, k2, k3, h1, and h2 (see colored area of Fig. 2d).

To characterize these local configurations of interest, we calculated the hyperfine and zero-field splitting (ZFS) constants for the non-equivalent divacancy sites using density functional theory (DFT). When possible, these values are paired with experimental measurements of these quantities from ref. 40. Both the theoretical and experimental results are summarized for axial and basal divacancy configurations in Fig. 3b–f (also in Supplementary Tables 1–4). From this, five divacancy groups could be identified based on their splitting constants, three (1–3) for the axial and two (4–5) for the basal plane configurations.

-

1.

The hexagonal axial configurations (hh-4H, h1h1-ssf, h2h2-ssf).

-

2.

The majority of cubic-like configurations (kk-4H, k1k1-ssf, and k3k3-ssf) showing similar splitting within their respective groups to group 1.

-

3.

The cubic-like k2k2-ssf divacancy presents an outlier splitting value compared to groups 1 and 2. This configuration forms in the stacking fault itself as shown in Fig. 2d.

Meanwhile, the basal plane divacancies for neighboring SiIIa and SiIIb nuclei sites as shown in Fig. 3a formed two subgroups, with distinct properties (see Fig. 3e and Supplementary Tables 2–4).

-

4.

The k3h2-ssf, h2k2-ssf, and bulk like kh-4H and hk-4H configurations.

-

5.

The k1h1-ssf and k2k1-ssf basal configurations.

a Spin density of an axial divacancy. Blue and green filled circles indicate the second neighbor silicon sites for which the hyperfine tensors were calculated. b The calculated and experimentally measured relative ground-state zero-field splitting parameter for each axial symmetric defect. D0 is equal to the ZFS of hh-4H configuration and PL1 center in the calculation of the theoretical and experimental parameters, respectively. The experimental results are reported in ref. 40. c, d Relative hyperfine parameters of SiIIa and SiIIb neighboring nuclei sites, which are depicted in a. Az0 is equal to the hyperfine splitting of hh-4H configuration and PL1 center in the calculation of the theoretical and experimental parameters, respectively. e Hyperfine splitting of basal plane divacancy configurations. Due to the low symmetry of basal plane configurations, we distinguish symmetrically non-equivalent sites, SiIIa-1 and SiIIa-2, and SiIIb-1, SiIIb-2, and SiIIb-3, in the neighbor shells of SiIIa and SiIIb shown in a.

In sum, the k2k2-ssf, k1h1-ssf, and k2k1-ssf divacancy configurations diverge from their defect counterparts within the quantum well’s influence.

These results show that a single 1FSF(3,2) Frank-type stacking fault in 4H-SiC has a marked perturbative effect on the spin density and derived properties of a large subset of the divacancy configurations in its region. Indeed, from the nine near fault configurations considered, three (one axial, and two basal plane) divacancies diverge from their bulk configurations. Interestingly, while the k2k2-ssf, k1h1-ssf, and k2k1-ssf configurations show differing hyperfine splittings and ZFS constants (Fig. 3b–f and Supplementary Tables 1–4) as compared to their unperturbed bulk-like counterparts, they maintain their sought-after magneto-optical and PL characteristics (see Supplementary Tables 1–5). Critically, the stacking fault also lowers the local conduction band minimum by ~0.24 eV, while the local charge defect states do not shift towards the valence band maximum.

Coincidentally, this slight change to the local band-gap could result in a dramatic improvement in the charge dynamics. Divacancy defects in SiC have a zero-phonon line (ZPL) emission around 1.1 eV and generally require ~1.3 eV to repump16. Lowering the local band-gap by 0.2 eV means that even at its lowest energy, the off-resonant pump laser can reset the charge state, resulting in significant improvements to charge stability. Therefore, the stacking fault opens pathways for the divacancy dark state (VV−) to more readily repopulate the bright state (VV0)16 via excitation laser and single-photon ionization as depicted in Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 2, stabilizing the qubit.

Experimental comparison

These results provide a means by which to interpret recent optically detected magnetic resonance (ODMR)24 and PL18 studies in 4H-SiC that reported unexpected divacancy-like color centers, labeled as PL5-PL77,24,27 and PL5’-PL6’18, that cannot be simply assigned to the known structural bulk 4H-SiC configurations (hh, kk, hk, kh)25. In many respects, the optical properties of these anomalous color centers observed in commercial 4H-SiC display properties of bulk divacancy configurations. However, unlike the known bulk divacancy centers25, PL5-7 show several outstanding characteristics, including stability during both room-temperature ODMR measurements7,24 and photo-ionization studies16. Additionally, the PL intensity of these color centers is unaffected by the introduction of an appropriate re-pump laser16. This is in stark contrast to known bulk divacancy configurations that typically exhibit a many-orders-of-magnitude change in their PL signal16.

This charge stability points to the fact that the PL5-7 defect spin is preferentially in its bright charge state under continuous off-resonant excitation, much like the predicted behavior of near-stacking fault divacancy configurations under excitation laser re-pump conditions. However, point defect-stacking fault complexes are rarely reported in experimental work on high-quality crystalline SiC samples. For the assignment of PL5-7 to the distinct k2k2-ssf, k1h1-ssf, and k2k1-ssf configurations to be plausible, the commercially available 4H-SiC wafers, which have been found to commonly feature PL5-PL724 and PL5’-PL6’18 signatures should harbor stacking faults as modeled above.

In order to validate this, we investigated multiple commercial sources of 0001-oriented (in Hexagonal Miller–Bravais indices notation) 4H-SiC wafers by means of X-ray diffraction at Sector 12 ID-D of the Advanced Photon Source (APS) (see the “Methods” section for technical details). Crystallographically, 1FSF(3,2) Frank-type stacking faults are synonymous with the presence of 6H polytypic inclusions in a bulk 4H crystal. We thus performed two types of X-ray measurements to isolate such 6H inclusions within several commercially available 4H crystals: (1) symmetric diffraction measurements were made of the crystal truncation rod in the vicinity of the 4H-(0004) and 4H-(0008) Bragg peaks to look for evidence of scattering contributions from a minority phase of 6H; and (2) non-symmetric diffraction measurements were performed at a scattering condition where 4H diffraction is forbidden, and 6H diffraction is allowed. Both measurements were designed to identify the presence of 6H inclusions that share lattice orientation with the 4H host, which would likely be the case for any 6H inclusion described by the 1FSF(3,2) stacking fault.

The results of the symmetric diffraction measurements are shown in Fig. 4a, b for one of the substrates tested. They show that the very strongly diffracting 4H-(0004) and 4H-(0008) Bragg peaks both feature weakly diffracting shoulders indicative of the presence of a second phase in the crystal with a slightly larger c-axis interplanar spacing. Fitting of these peaks indicate that this minority phase has a c-axis interplanar spacing that is 0.05 ± 0.01% larger than that of bulk 4H-SiC. Further evidence of the presence of 6H inclusions is shown in the results of the non-symmetric X-ray diffraction measurement (Fig. 4c, d). The observation of 6H-\((10\bar 14)\) and 6H-\((10\bar 18)\) Bragg peaks where 4H diffraction is forbidden unambiguously demonstrate the presence of inclusions of the 6H polytype in the 4H host crystal. These results confirm that 1FSF(3,2) Frank-type stacking faults that result in 6H polytype inclusions in 4H-SiC are readily observed in typical commercial wafers. Specifically, from the data shown in Fig. 4, we estimate a 0.128 ± 0.012 volume percent of 6H inclusions in that particular 4H wafer. Similarly, the synchrotron diffraction measurements we performed revealed the same fingerprints of 6H inclusions in all of the 4H materials investigated, with varying absolute quantities of volumetric fraction.

a Shows the (0004)/(0008) L-scan of 4H-SiC and contributions of the detected (0006)/(00012) contributions from 6H-SiC. We note the 4H and 6H components fitted simultaneously as fully inter-related doublets. b Zoom-in of the 4H-(0008) diffraction peak skew due to the presence of 6H-SiC polytypic inclusions. c and d The non-specular \((10\bar 14)\) and \((10\bar 18)\) peaks of 6H, respectively.

Though their origins and locations cannot be deduced from our X-ray measurements, these stacking faults have been reported to form preferentially near the surface in as-purchased SiC wafers, possibly induced by face polishing41. In this case, point defect-stacking fault complexes would be expected in higher concentration in the near surface region of any commercially processed SiC sample. This prediction was verified via ODMR measurements in an inhomogeneous magnetic field to locate different axial divacancy color centers in the sample (see Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). Indeed, it can be confirmed that the spatial distribution of the PL6 center is significantly different from that of the hh, kk, hk, and kh (PL1–4) divacancies as a function of substrate depth. The hh, kk, hk, and kh divacancies were found to be uniformly distributed through the sample, whereas the PL6 qubits were concentrated near the surfaces, matching the expected distribution of stacking faults.

Building on these results, we propose that the as-yet-unidentified divacancy-like color centers PL5–7 observed in commercial 4H-SiC are related to specific point defect structures positioned in the vicinity of a stacking fault that acts as a local quantum well within 4H-SiC. Specifically, based on our modeling of hyperfine splitting, our experimental measurement of 6H inclusions in 4H bulk, and our observation of surface dependence of PL6 signatures, we stipulate that the k1h1-ssf, k2k2-ssf, and k2k1-ssf configurations account for the previously unattributed PL5–7 signatures. The calculated hyperfine, zero-field-splitting, and ZPL magneto-optical parameters obtained for the k2k2-ssf configuration agree well with the experimental data reported for PL6 divacancy-related qubit (see Fig. 3 and Supplementary Notes 2–4). Consequently, we assign the k2k2-ssf stacking fault-divacancy configuration to the PL6 signature and the experimentally observed room temperature stability of the PL6 center is attributed to the quantum-well stabilization mechanism discussed above and depicted in Fig. 1d.

Compared to the PL6 center, the basal-plane oriented PL5 and PL7 centers have more sparsely available experimental data. Nonetheless, they have several important experimentally observed similarities to the PL6 center, including similar optical-transition and spin-transition energies, a nearly identical ODMR stability with temperature, and a similar ODMR variation across wafers in multi-wafer studies24. These studies, in combination with our models, provide an understanding that the PL5 and PL7 centers are basal-plane-oriented homologues of the c-axis-oriented PL6 center. Although we cannot uniquely distinguish each center, we assign the PL5 and PL7 centers to the k1h1-ssf and k2k1-ssf subgroup configurations of 6H polytypic inclusions in 4H-SiC.

Discussion

We demonstrated that the quantum well of a stacking fault in 4H-SiC can give rise to a point defect qubit stabilization mechanism, without the application of a re-pumping laser16. Furthermore, we found an association between the Frank-type stacking faults in commercial 4H-SiC materials and the presence of the PL5–7 defect qubits. In this context, we were able to identify the PL5–7 (k1h1-ssf, k2k2-ssf, and k2k1-ssf) room-temperature qubits as divacancies in stacking-fault structures.

Our results demonstrate the prospect of utilizing proximity to stacking faults as a means to engineer and tailor the properties of divacancy complexes in SiC. Such an approach may provide a practical route to synthesize qubits with enhanced photoionization and room temperature stability, given that stacking faults are common low-energy defects in systems that display prolific polytypism. In SiC, stacking faults have been reported to form as a consequence of different fabrication treatments, such as doping31, implantation42, irradiation43, annealing31, plastic deformation44, surface polishing41, and even due to optical irradiation45. Any of these approaches can be harnessed to intentionally introduce stacking faults in specific locations of a 4H host crystal. Finally, recent developments in 3D engineering of defect creation46,47,48,49 make it possible to synthesize near-stacking fault divacancies.

The study of point defects embedded in extended defects50 presents unique challenges and complexities as compared to that of point defects in single crystal bulk materials29. However, these structures also provide opportunities to broaden the palette of technologically applicable point defect qubits with superior functionality. We explore this general approach through the specific example of a single stacking fault in 4H-SiC that stabilizes divacancy qubits in its vicinity. Stacking faults51,52, polytype inclusions53, and other means54,55 of generating local quantum wells are readily available in many semiconductor systems that are suitable hosts for point defect qubits. For example, diamond, an important material for optically addressable spin qubits, also contains stacking faults51. Moreover, our underlying theory of defect qubits in quantum wells could be generalized to many semiconductor systems56. Thus, tuning the optoelectronic properties of point defects via local quantum wells could be an important strategy for discovering a large and robust class of new spin qubits.

Methods

Computational methods

In our first principles DFT calculations, we use Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)57, a plane wave basis set of 420 eV, and the projector-augmented wave method (PAW)58 to describe electronic states of different defective 4H-SiC supercells. Perdew–Burke–-Ernzerhof (PBE)59 and Heyd–Scuseria–Ernzerhof (HSE06)60 exchange correlation functionals are employed to include exchange-correlation effects of the many electron system at different levels of approximation. To preserve periodicity, two single stacking faults are included and placed 27.8 Å away from each other in our supercell models, which were fixed to have a total size of 55.7 Å in the c direction. The large axial size of the supercell allows us to calculate and compare near-stacking fault, as well as bulk-like divacancies using the same model by tuning the proximity of the defect to the stacking fault plane. Following the guidelines of refs. 25,61, the basal planar size as well as the k-point grid density are optimized for all the magneto-optical parameters calculated in this study. To obtain the most accurate ground state hyperfine tensors of first neighbor 13C and second neighbor 29Si nuclei, the HSE06 functional was used on a PBE relaxed supercell of 704 atoms with 3 × 3 × 1 k-point sampling. To obtain the ground state ZFS, we used a 1584 atom supercell with 2 × 2 × 1 k-point set, PBE Kohn–Sham wavefunctions, and our in-house implementation for the ZFS tensor calculation62. In our computational study we concentrated on the most reliable ground state hyperfine and ZFS data, and we also calculated the ZPL energies (see Supplementary Note 4).

For the band structure calculations, we used the HSE0660 hybrid functional, a 420 eV plane wave cut-off energy, and 12 × 12 × 6 and 12 × 12 × 1 k-point sets for 4H and the stacking fault model, respectively. It has been shown by a multireference method beyond DFT that HSE06 DFT functional provides accurate band structure and excitation energies of divacancy defects in SiC63.

X-ray measurements

The XRD experiments were carried out at beamline 12 ID-D of the APS, using a six-axis goniometer specifically developed for high-resolution crystal truncation rod X-ray studies. The sample that was studied was a (0001)-surface-oriented 4H-SiC high purity semi-insulating wafer purchased from Cree Inc. An X-ray beam with a photon energy of 20 keV was used for all diffraction experiments. Two general diffraction geometries were used depending on the diffraction conditions targeted: symmetric (specular) and non-symmetric (off-specular). In specular X-ray diffraction, the incident and exit angle of the incoming and diffracted beams are equal, such that the photon momentum transfer (or q-vector) is oriented along the surface normal. Since the (0001) crystallographic planes were parallel to the wafer surface, this specular diffraction geometry gave access to information about the (0001) layer spacing in the crystal. The non-specular X-ray diffraction geometry was utilized to reach positions along an off-specular crystal truncation rod where 6H-SiC diffraction was allowed, but 4H-SiC diffraction was forbidden. Both geometries involved measurements of a crystal truncation rod along the out-of-plane c-axis crystallographic direction, known as L-scans. These were angular sweeps of appropriate goniometer axes that spanned equal spaced steps along the crystal truncation rod of interest, (000L) for specular and \((10\bar 1L)\) for off-specular. The units of L in the figure are given as reciprocal lattice units of the 4H-SiC lattice. The (0004)/(0008) 4H and 6H diffraction doublets were fitted using Voigt doublets that accounted for consistent shape factors and intensity ratios within and throughout both diffraction windows, respectively. The volumetric fraction was approximated by using the ratio of areas for the diffraction doublets.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors on reasonable request, see author contributions for specific data sets.

References

Wrachtrup, J. & Jelezko, F. Processing quantum information in diamond. J. Phys.-Condens. Matter 18, S807–S824 (2006).

Weber, J. R. et al. Quantum computing with defects. PNAS 107, 8513–8518 (2010).

Aharonovich, I., Englund, D. & Toth, M. Solid-state single-photon emitters. Nat. Photonics 10, 631 (2016).

Maze, J. R. et al. Nanoscale magnetic sensing with an individual electronic spin in diamond. Nature 455, 644–647 (2008).

Kucsko, G. et al. Nanometre-scale thermometry in a living cell. Nature 500, 54 (2013).

Aslam, N. et al. Nanoscale nuclear magnetic resonance with chemical resolution. Science 357, 67–71 (2017).

Koehl, W. F., Buckley, B. B., Heremans, F. J., Calusine, G. & Awschalom, D. D. Room temperature coherent control of defect spin qubits in silicon carbide. Nature 479, 84 (2011).

Christle, D. J. et al. Isolated electron spins in silicon carbide with millisecond coherence times. Nat. Mater. 14, 160–163 (2015).

Widmann, M. et al. Coherent control of single spins in silicon carbide at room temperature. Nat. Mater. 14, 164–168 (2015).

Kraus, H. et al. Room-temperature quantum microwave emitters based on spin defects in silicon carbide. Nat. Phys. 10, 157–162 (2014).

Whiteley, S. J. et al. Spin–phonon interactions in silicon carbide addressed by Gaussian acoustics. Nat. Phys. 15, 490–495 (2019).

Jelezko, F. & Wrachtrup, J. Single defect centres in diamond: a review. Phys. Status Solidi A 203, 3207–3225 (2006).

Awschalom, D. D., Bassett, L. C., Dzurak, A. S., Hu, E. L. & Petta, J. R. Quantum spintronics: engineering and manipulating atom-like spins in semiconductors. Science 339, 1174–1179 (2013).

Fu, K.-M. C., Santori, C., Barclay, P. E. & Beausoleil, R. G. Conversion of neutral nitrogen-vacancy centers to negatively charged nitrogen-vacancy centers through selective oxidation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 121907 (2010).

Aslam, N., Waldherr, G., Neumann, P., Jelezko, F. & Wrachtrup, J. Photo-induced ionization dynamics of the nitrogen vacancy defect in diamond investigated by single-shot charge state detection. N. J. Phys. 15, 013064 (2013).

Wolfowicz, G. et al. Optical charge state control of spin defects in 4H-SiC. Nat. Commun. 8, 1876 (2017).

Golter, D. A. & Lai, C. W. Optical switching of defect charge states in 4H-SiC. Sci. Rep. 7, 13406 (2017).

Magnusson, B. et al. Excitation properties of the divacancy in 4H-SiC. Phys. Rev. B 98, 195202 (2018).

Dhomkar, S., Zangara, P. R., Henshaw, J. & Meriles, C. A. On-demand generation of neutral and negatively charged silicon-vacancy centers in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 117401 (2018).

Balasubramanian, G. et al. Ultralong spin coherence time in isotopically engineered diamond. Nat. Mater. 8, 383 (2009).

Buckley, B. B., Fuchs, G. D., Bassett, L. C. & Awschalom, D. D. Spin-light coherence for single-spin measurement and control in diamond. Science 330, 1212 (2010).

Anderson, C. P. et al. Electrical and optical control of single spins integrated in scalable semiconductor devices. Science, in press; Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1906.08328 (2019).

Riedel, D. et al. Resonant addressing and manipulation of silicon vacancy qubits in silicon carbide. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 226402 (2012).

Falk, A. L. et al. Polytype control of spin qubits in silicon carbide. Nat. Commun. 4, 1819 (2013).

Davidsson, J. et al. First principles predictions of magneto-optical data for semiconductor point defect identification: the case of divacancy defects in 4H-SiC. N. J. Phys. 20, 023035 (2018).

Davidsson, J. et al. Identification of divacancy and silicon vacancy qubits in 6H-SiC. Appl. Phys. Lett. 114, 112107 (2019).

Klimov, P. V., Falk, A. L., Christle, D. J., Dobrovitski, V. V. & Awschalom, D. D. Quantum entanglement at ambient conditions in a macroscopic solid-state spin ensemble. Sci. Adv. 1, e1501015 (2015).

Tsuchida, H., Kamata, I. & Nagano, M. Formation of basal plane Frank-type faults in 4H-SiC epitaxial growth. J. Cryst. Growth 310, 757–765 (2008).

Lohrmann, A. et al. Single-photon emitting diode in silicon carbide. Nat. Commun. 6, 7783 (2015).

Sridhara, S. G., Carlsson, F. H. C., Bergman, J. P. & Janzén, E. Luminescence from stacking faults in 4H SiC. Appl. Phys. Lett. 79, 3944–3946 (2001).

Kuhr, T. A., Liu, J., Chung, H. J., Skowronski, M. & Szmulowicz, F. Spontaneous formation of stacking faults in highly doped 4H–SiC during annealing. J. Appl. Phys. 92, 5863–5871 (2002).

Izumi, S., Tsuchida, H., Kamata, I. & Tawara, T. Structural analysis and reduction of in-grown stacking faults in 4H–SiC epilayers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 86, 202108 (2005).

Si, W., Dudley, M., Shuang Kong, H., Sumakeris, J. & Carter, C. Investigations of 3C-SiC inclusions in 4H-SiC epilayers on 4H-SiC single crystal substrates. J. Electron. Mater. 26, 151–159 (1997).

Castelletto, S. et al. A silicon carbide room-temperature single-photon source. Nat. Mater. 13, 151–156 (2014).

Feng, G., Suda, J. & Kimoto, T. Characterization of stacking faults in 4H-SiC epilayers by room-temperature microphotoluminescence mapping. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 221906 (2008).

Kamata, I., Zhang, X. & Tsuchida, H. Photoluminescence of Frank-type defects on the basal plane in 4H–SiC epilayers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 172107 (2010).

Chen, B. et al. Tuning minority-carrier lifetime through stacking fault defects: the case of polytypic SiC. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 132108 (2012).

Benamara, M. et al. Structure of the carrot defect in 4H-SiC epitaxial layers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 86, 021905 (2005).

Miao, K. C. et al. Electrically driven optical interferometry with spins in silicon carbide. Sci. Adv., in press; Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1905.12780 (2019).

Falk, A. L. et al. Optical polarization of nuclear spins in silicon carbide. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 247603 (2015).

Ushio, S. et al. Formation of double stacking faults from polishing scratches on 4H-SiC (0001) substrate. In Silicon Carbide and Related Materials 2013(eds Okumura, H. et al.), Vol. 778, 390—393 (Trans Tech Publications, 2014).

Chen, B. et al. Pinning of recombination-enhanced dislocation motion in 4H–SiC: Role of Cu and EH1 complex. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 212110 (2010).

Regula, G. & Yakimov, E. B. Effect of low energy electron beam irradiation on Shockley partial dislocations bounding stacking faults introduced by plastic deformation in 4H-SiC in its brittle temperature range. Superlattices Microstruct. 99, 226–230 (2016).

Pichaud, B., Regula, G. & Yakimov, E. B. Electrical and optical properties of stacking faults introduced by plastic deformation in 4H-SiC. AIP Conf. Proc. 1583, 161–164 (2014).

Galeckas, A., Linnros, J. & Pirouz, P. Recombination-induced stacking faults: evidence for a general mechanism in hexagonal SiC. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 025502 (2006).

Chen, Y.-C. et al. Laser writing of scalable single colour centre in silicon carbide. Nano Lett. 19, 2377–2383 (2019).

Ohshima, T. et al. Creation and functionalization of defects in SiC by proton beam writing. Mater. Sci, Forum https://www.scientific.net/MSF.897.233 (2017).

Kraus, H. et al. Three-dimensional proton beam writing of optically active coherent vacancy spins in silicon carbide. Nano Lett. 17, 2865–2870 (2017).

Radulaski, M. et al. Scalable quantum photonics with single color centers in silicon carbide. Nano Lett. 17, 1782–1786 (2017).

Xi, J., Liu, B., Zhang, Y. & Weber, W. J. Ab initio study of point defects near stacking faults in 3C-SiC. Comput. Mater. Sci. 123, 131–138 (2016).

Zhu, W. Defects in diamond. In Diamond: Electronic Properties and Applications (eds Pan, L. S. & Kania, D. R.) 175–239 (Springer US, 1995).

Lopez, F. J., Hemesath, E. R. & Lauhon, L. J. Ordered stacking fault arrays in silicon nanowires. Nano Lett. 9, 2774–2779 (2009).

Kriegner, D. et al. Unit cell structure of crystal polytypes in InAs and InSb nanowires. Nano Lett. 11, 1483–1489 (2011).

Xian, L., Kennes, D. M., Tancogne-Dejean, N., Altarelli, M. & Rubio, A. Multiflat bands and strong correlations in twisted bilayer boron nitride: doping-induced correlated insulator and superconductor. Nano Lett. 19, 4934–4940 (2019).

Proscia, N. V. et al. Near-deterministic activation of room-temperature quantum emitters in hexagonal boron nitride. Optica 5, 1128–1134 (2018).

Zhou, Y. et al. Room temperature solid-state quantum emitters in the telecom range. Sci. Adv. 4, eaar3580 (2018).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal–amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14251–14269 (1994).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Heyd, J., Scuseria, G. E. & Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened Coulomb potential. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 8207 (2003).

Ivády, V., Abrikosov, I. A. & Gali, A. First principles calculation of spin-related quantities for point defect qubit research. Npj Comput. Mater. 4, 76 (2018).

Ivády, V., Simon, T., Maze, J. R., Abrikosov, I. A. & Gali, A. Pressure and temperature dependence of the zero-field splitting in the ground state of NV centers in diamond: a first-principles study. Phys. Rev. B 90, 235205 (2014).

Bockstedte, M., Schütz, F., Garratt, T., Ivády, V. & Gali, A. Ab initio description of highly correlated states in defects for realizing quantum bits. npj Quantum Mater. 3, 31 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank Christopher P. Anderson, Gary Wolfowicz, and Sean Sullivan for careful reading of the manuscript. We also thank Angel Yanguas-Gil and Hua Zhou for experimental assistance. VI acknowledges the support from the MTA Premium Postdoctoral Research Program. This work was financially supported by the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation through WBSQD2 project (Grant No. 2018.0071). Support from the Swedish Government Strategic Research Areas in Materials Science on Functional Materials at Linköping University (Faculty Grant SFO-Mat-LiU No. 2009-00971) and the Swedish e-Science Centre (SeRC), the Swedish Research Council (VR 2016-04068), and the Carl-Trygger Stiftelse för Vetenskaplig Forskning (CTS 15:339) is gratefully acknowledged. Analysis of the model Hamiltonians parameters was supported by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation in the framework of Increase Competitiveness Program of NUST MISIS (No. K2-2019-001) implemented by a governmental decree dated 16 March 2013, No. 211. A.G. acknowledges the Hungarian NKFIH grants No. KKP129866 of the National Excellence Program of Quantum-coherent materials project, No. 127902 of the EU QuantERA Nanospin project, EU H2020 Quantum Technology Flagship project ASTERIQS (Grant No. 820394), the NVKP project (Grant No. NVKP_16-1-2016-0043), as well as the National Quantum Technology Program (Grant No. 2017-1.2.1-NKP-2017-00001). The calculations were performed on resources provided by the Swedish National Infrastructure for Computing (SNIC 2016/1-528, SNIC 2017/11-8, SNIC 2018/3-625) at the National Supercomputer Centre (NSC) and by Linköping University (LiU-2015-00017-60). Work performed at Argonne (the design, execution, and analysis of X-ray experiments), was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Science and Engineering Division. X-ray measurements were performed at the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. M. V. H. acknowledges support from the Center for Nanoscale Materials, a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. N.D., S.O.H., F.J.H., and D.D.A. were supported by the DOE, Office of Basic Energy Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.I. and N.D. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. Calculations were performed by V.I. and J.D. with input from N.T.S., I.A.A., and A.G. Optical experiments were performed by A.L.F., P.V.K., and D.D.A. X-ray measurements were performed by N.D., S.J.W., S.O.H., M.V.H., and F.J.H. The computational and experimental results were analyzed with contributions from all authors. The research was initiated and supervised by A.G.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Georgy Astakhov and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ivády, V., Davidsson, J., Delegan, N. et al. Stabilization of point-defect spin qubits by quantum wells. Nat Commun 10, 5607 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13495-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13495-6

This article is cited by

-

Characterization of just one atom using synchrotron X-rays

Nature (2023)

-

Driving ultrafast spin and energy modulation in quantum well states via photo-induced electric fields

npj Quantum Materials (2022)

-

Room-temperature photonic logical qubits via second-order nonlinearities

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Dipolar spin relaxation of divacancy qubits in silicon carbide

npj Computational Materials (2021)

-

Stone–Wales defects in hexagonal boron nitride as ultraviolet emitters

npj Computational Materials (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.