SO HOW DID WE GET HERE?

The Archaeology Data Service (ADS) is the United Kingdom's national digital data archive for archaeology and the historical environment, and the longest serving repository for archaeological data in the world. In 2016, it celebrated its twentieth anniversary. The ADS was originally established in 1996 with two members of staff and a budget of approximately £60,000 per annum (Richards Reference Richards, McManamon, Stout and Barnes2008; Richards et al. Reference Richards, Niven, Jeffrey and Gaffney2013). It now has 14 members of staff and an annual budget of around £750,000. Having been set up as part of the Art and Humanities Data Service (AHDS), with an annual core grant, the ADS was the only one of the AHDS service providers retained by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) beyond 2008, in recognition of the fact that most archaeological data are special and are a primary source that, once lost, cannot be recovered. Whereas most historical sources can be re-digitized, one cannot go back and re-excavate an archaeological site. However, the AHRC's decision also reflected the fact that the ADS had demonstrated that it could generate alternative sources of income. It now receives no external grant aid support and is entirely dependent on generating its operating costs via research and development, consultancy, and preservation services. Over 75% of its annual income is derived from project funding and research and development grants, with major contributions from the European Commission and Historic England. A growing proportion of its income also comes from the commercial contract archaeology sector, and the level of external income generation demonstrates its value for money and cost-effectiveness.

As of October 2016, the ADS Collections Management System recorded 2,143,497 files in our systems, comprising 12 TB of data. However, the more significant statistic is the number of recorded processes carried out on those files—21,327—to ensure their long-term preservation. Unlike a physical archive, digital preservation requires active curation, migrating files formats to current versions to ensure their reusability in new software. The ADS is compliant with the Open Archival Information Standard (OAIS) ISO 14721 standard for digital repositories (Lavoie Reference Lavoie2014). Since March 2011, the ADS has been accredited with the Data Seal of Approval, an international “kite-mark” for digital repositories, becoming one of the first UK repositories to gain this recognition, second only to the UK Data Archive (Mitcham and Hardman Reference Mitcham and Hardman2011). In 2012, it was awarded the Digital Preservation Coalition's first Decennial Award for the most outstanding contribution to digital preservation—in all disciplines—in the last decade.

Over the last 20 years, the ADS has inevitably witnessed some significant changes in the digital preservation landscape. From the outset, ADS set out to preserve all types of digital research data produced by archaeologists. Those data have grown both in variety and in size. For example, an early collaborative project looked at the wide variety of data generated by deep underwater archaeology, particularly data automatically logged by remote vehicles (Drap Reference Drap2009). As well as the complexities of new data formats, there are also new forms of communication, such as the widespread use of social media, which bring their own preservation challenges (Jeffrey Reference Jeffrey2012). “Big Data” has also become a buzz phrase in computer-based analysis but, while archaeological datasets are not generally large by external standards, we have had to address how best we can archive, and disseminate, some of the terabytes of data produced by laser survey (Austin et al. Reference Austin, Mitcham, Richards, Posluschny, Lambers and Herzog2008). As bandwidth increases, there is also an increasing appetite for online visualization of complex 3D data. A recent project involved collaboration with the CNR-ISTI laboratory in Pisa in order to develop a web-based tool for the visual analysis of 3D stratigraphic layers (Galeazzi et al. Reference Galeazzi, Callieri, Dellepiane, Charno, Richards and Scopigno2016). However, even apparently simple data types may require intervention to ensure that they do not rely on proprietary features, and ADS staff have undertaken an analysis of the complexities of archiving PDF files, the most common format for the deposit of text reports (Evans and Moore Reference Evans and Moore2014).

This article will explore some of the lessons learned over the last 20 years. The initial focus will be on the ubiquitous “gray literature”—the unpublished fieldwork reports that have come to dominate the archaeological record, and some of the ways of dealing with them. It will then consider more ambitious forms of dissemination, and the concept of blurring the distinction between publication and archive. It will attempt to define the core elements of an adequate fieldwork archive in the twenty-first century. The next section will consider how ADS has managed to become a self-sustaining digital archive and discuss business models for archiving in the heritage sector. However, there is no point in spending money on preservation if no one uses the archive. This therefore leads into a discussion of reuse and the cost-effectiveness of digital archiving. Finally, before attempting to draw some conclusions, the paper will end with a consideration of data silos and how they can be avoided. With the increase in the number of archaeological digital repositories around the world, it is essential to ensure interoperability between them, and means of achieving that will be discussed.

FIFTY SHADES OF GRAY

One of the greatest challenges facing the archaeological profession is how to make available the results of the extensive fieldwork projects undertaken in advance of modern development. The quantity of fieldwork has outstripped the capability of traditional modes of publication to keep pace, and it is even difficult to find a comprehensive record of where and how many archaeological projects have taken place (Evans Reference Evans2013). The outcome in most countries has been a mountain of unpublished fieldwork reports, the so-called gray literature. The problem with gray literature has been the difficulty of knowing that it exists and then of tracking it down. Generally produced in just one or two copies—one for the client and one for the regional HER (Historic Environment Record) or SHPO (State Historic Preservation Office)—these reports have been difficult for researchers to access. In an important paper, Richard Bradley (Reference Bradley2006) lamented the fact that most teaching and research taking place in universities was way out of date, as it failed to take account of new discoveries locked in the gray literature. Similar problems have been reported in countries across the world.

In the United Kingdom, one solution has been the OASIS project, now a collaboration between the ADS and the national heritage agencies for England and Scotland: Historic England and Historic Environment Scotland respectively (Hardman and Richards Reference Hardman, Richards, Doerr and Sarris2003). OASIS is an online data collection form that collects key information about any type of archaeological fieldwork according to national recording standards and allows the user to upload a copy of their report. Users must enter core metadata, including the location of the project and who undertook the work, as well as standardized period and subject terms, a summary of what was found, and what the archive contains. Access to the form is provided to the regional archaeological or planning office, as well as the appropriate national agency. Once the form has been signed off by the archaeologists in the planning office or (by agreement) in the national agency, any attached report is given a DOI (Digital Object Identifier) and released within the ADS library of unpublished fieldwork reports. As of February 2017, there were 40,816 reports available online, providing an essential resource for archaeological research, a figure that grows at the rate of approximately 200 a month. Completing an OASIS form has become a requirement in Scotland and in most regions in England, but the main driver for usage of the form came from the contract archaeologists themselves, keen to promote their work online. Ironically, the gray literature, available Open Access, is now far more accessible than conventional publications in monographs or regional county society journals. Even if libraries subscribe to these, they are usually available only in the library or, if they are online, they are still behind a subscription paywall, accessible only to the privileged few whose institutions have subscribed. It is a noticeable trend that, as the gray literature has gone online, and has largely replaced traditional journal articles, it has also become more professional and represents adequate publication in its own right. Completion of an OASIS record is not yet routine in the voluntary or community archaeology sector, or by university-based archaeologists, but a major revision, currently underway and due for release in 2018, is designed to change that. The new OASIS will also allow access to museums, forewarning them of physical archives destined for their store.

One of the remaining challenges has been the adequate indexing of such reports. The OASIS form requires the manual entry of keywords and was liable to people mistyping or inventing terms that were not part of agreed-upon nationally controlled vocabularies. In the Archaeotools project, the ADS explored the use of Natural Language Processing (NLP) to automatically generate index terms for text reports (Jeffrey et al. Reference Jeffrey, Richards, Ciravegna, Waller, Chapman, Zhang and Coveney2009; Richards et al. Reference Richards, Tudhope, Vlachidis, Barceló and Bogdanovic2015; Richards, Jeffrey, et al. Reference Richards, Jeffrey, Waller, Ciravegna, Chapman, Zhang, Kansa, Kansa and Watrall2011; Vlachidis and Tudhope Reference Vlachidis and Tudhope2013). Further work, in collaboration with a team from the University of South Wales in the STAR and STELLAR projects, has led to the development of online tools to allow those doing data entry to draw their terms from controlled pick lists (Tudhope, Binding, et al. Reference Tudhope, Binding, Jeffrey and Vlachidis2011; Tudhope, May, et al. Reference Tudhope, May, Binding and Vlachidis2011). These projects also allowed the integration of gray literature with other forms of fieldwork data via a semantic cross-search, with a mapping to the international high-level ontology for the cultural heritage sector, the CIDOC CRM (Doerr Reference Doerr2003). In the next generation of OASIS, NLP will be used to analyze a report as it is uploaded and will suggest suitable keywords, drawn from the controlled vocabularies. In previous experiments, NLP has achieved an 80% success rate in identifying the same terms that the archaeologist would enter by hand. The user will then be able to accept or reject suggested terms, and to add alternatives, thereby leading to a significant increase in efficiency, as well as much better-quality metadata.

BLURRING BOUNDARIES

Despite using an online medium for dissemination, the gray literature report remains a traditional form of publication. While reports may increasingly be accompanied by other data types, including images or databases, they rarely link to them in a way that allows the reader to drill down to verify a particular interpretation. Digital media should allow for much more ambitious linking to primary data, which has been the aspiration of our sister e-journal, Internet Archaeology, from the outset (Richards Reference Richards, Tudhope, Vlachidis, Barceló and Bogdanovic2015).

From its first issue in 1996, the journal has endeavored to promote links between the publication of research and supporting datasets. The award-winning Linking Electronic Archives and Publications (LEAP) project set out to provide a series of exemplars of linked publications in Internet Archaeology with archives held by the ADS, including the major fieldwork projects at Merv, Silchester, Troodos, and Whittlewood (Richards, Winters, and Charno Reference Richards, Winters, Charno, Redö and Szeverényi2011). Of course, this relationship is not exclusive, and Internet Archaeology has also published articles linked to datasets held in other data archives, including tDAR in the United States (Holmberg Reference Holmberg2010). With its recent move to becoming a full Open Access journal, Internet Archaeology has become the journal of choice for many archaeologists who wish to promote access to their research and data.

In 2013, Internet Archaeology introduced another publication model to encourage researchers to provide access to their datasets: the data paper. The concept of the data paper was developed in the physical sciences and has been extended to archaeology via the Journal of Open Archaeological Data, established at University College London under the auspices of Ubiquity Press. A data paper is generally a short paper that simply describes and summarizes a research dataset and outlines how it might be reused. It is generally a condition of publication that the dataset must have been deposited in an archive and have been allocated a DOI. Thus, for example, a paper by Bevan and Conolly on the Antikythera survey project (Reference Bevan and Conolly2012) references a dataset held by the ADS (Bevan and Conolly 2014). Internet Archaeology has developed the concept of the data paper further, adding a published review of the dataset, by a named external reviewer (e.g., Williams et al. Reference Williams, Ulm, Smith and Reid2014).

WHAT IS AN ADEQUATE ARCHAEOLOGICAL DIGITAL ARCHIVE?

Twenty years ago, the establishment of ADS and Internet Archaeology met with some skepticism from some members of the academic world. Given the current emphasis on Open Data and on Open Access to research publications, stemming from both government and funding agencies, it seems as if the establishment has finally caught up. However, if digital archiving and dissemination is to be a routine part of archaeological practice, it becomes even more important to define what we mean by a digital archive. From the 1990s, the AHDS developed a series of Guides to Good Practice (Mitcham et al. Reference Mitcham, Niven, Richards, Andreas Rauber, Kaiser, Guenthier and Constantopoulos2010) that were published as hard copy handbooks as well as being made freely available online; the ADS editions covered domain-specific data types, such as geophysical survey, aerial photography, and GIS. The purpose of the guides was not to standardize or even advise how specific techniques should be employed. Instead, their role was to define the file formats and metadata standards to follow, if a particular technique was being used, in order to safeguard long-term preservation and facilitate data reuse. The guides were aimed at those preparing data for archival deposit and those running digital repositories. Over the years, the guides have been enhanced and updated, with a major upgrade to a wiki-based system undertaken jointly with the U.S.-based Digital Antiquity consortium (Niven Reference Niven2013), and new sections to cover additional data types, most recently dendrochronology (Brewer and Jansma Reference Brewer and Jansma2016) and thermoluminescence (Kazakis and Tsirliganis Reference Kazakis and Tsirliganis2016).

One of the first guides, aimed at fieldworkers, had a slightly different focus, as it attempted to define the minimum standard for a digital archive from an excavation (Richards and Robinson Reference Richards and Robinson2000). In the commercial archaeological environment, where the primary driver can be to keep costs to a minimum, it is essential that those setting the specifications for archaeological work specify what they believe should be part of the archive. The fieldwork guide attempted to define a sliding scale of digital archive, according to the importance of a project. For example, a small site evaluation or watching brief yielding few archaeological features would not warrant a major investment in an archive, although it would still be important to preserve some record of the negative evidence, via an OASIS record. On the other hand, in 2000, the minimum standard for the digital archive accompanying a major project was defined as comprising several key elements (Table 1). These features were regarded as the minimum needed to allow future reuse of a fieldwork archive, on the basis that the archive should be seen as a standalone resource. In practice, some 15 years later, very few projects meet these minimum standards. In particular, stratigraphic matrices are rarely preserved, and spreadsheets of finds and animal bones (nowadays often developed by independent specialists) are not regarded as part of the core archive. Instead, a text report and a selection of digital photographs of trenches are too often regarded as the project archive. One suspects, however, that far more primary data may have been collected in digital format, and may well have been born digital. In 2012, it was estimated that there were some 2.2 GB of undeposited digital data comprising over 1.25 million files languishing in the hands of archaeological contractors in England (Smith and Tindall Reference Smith and Tindall2012). Cost is undoubtedly a key factor here, but the profession needs to take its responsibilities seriously, and the deposit of a proper digital archive should be part of the standard workflow for any archaeological project, undertaken online on completion of a project. This need not be time-consuming, but data archives and archaeological curators need to agree on what is the minimum standard for the twenty-first century and enforce it. This is one of the greatest challenges facing archaeological repositories today.

TABLE 1. Minimum Standards for a Research-Level Digital Archive (after Richards and Robinson Reference Richards and Robinson2000).

COVERING THE COSTS OF DIGITAL CURATION

Digital archiving requires human intervention, and that comes at a cost. One of the most significant achievements of ADS has been the development of a business model designed to ensure that it is self-sufficient and sustainable, the key prerequisite for any archive. While ADS was initially supported by research council annual grants to provide a free archiving service for university-based researchers, it was soon recognized that the majority of archaeological research data was actually produced outside higher education, in the commercial and public sectors—variously described as development control or contract archaeology, rescue archaeology, or, in continental Europe, preventative archaeology. Most countries, including both the United Kingdom and the United States, follow the principle that “the polluter pays”; that is, those funding the development should also pay for any archaeological work deemed necessary. In the United Kingdom, this traditionally includes any charges levied by the museum for the long-term deposit of the physical archive—including the artifacts and the documentary, photographic, and drawn record of the fieldwork. In both the United Kingdom and the United States, this model has been extended to include the digital archive. A one-off charge levied at the point of deposit pays for the digital preservation. The charge can be passed on by the archaeologist undertaking the fieldwork to the funding body—whether developer, government body, or the research council—ensuring that the data can remain freely available as Open Data to all users.

In the case of ADS, the deposit charge pays for the accessioning of the data; the creation, where necessary, of a preservation version in open formats; and of a dissemination version made available from a project web page, with a DOI. A proportion of the deposit charge is set aside in an endowment fund to cover the cost of future migration, although our experience shows that, if the appropriate steps are taken at the point of accession, then future costs can be minimized (Richards et al. Reference Richards and Hardman2010). This business model works well in a discipline in which most research, including fieldwork, is undertaken on a project-funding basis. For large projects, the digital preservation charges will generally be less than 1% of the overall project budget, although for smaller projects (such as a geophysical survey) they can represent a much higher proportion. Here a subscription model may be more appropriate, whereby geophysics contractors pay an annual subscription fee that allows them to deposit a restricted number of project archives per year. While a state grant-funding model for digital archiving has been pursued in some countries, it would be politically unacceptable in the United Kingdom, and while it might seem more attractive in terms of ensuring a regular income stream, experience shows that government funding is never guaranteed and is vulnerable to changes in administration and policy, particularly in times of austerity when archaeology and heritage become soft targets.

Experience also shows, however, that many archaeologists still fail to safeguard the future of their data by depositing it in a trusted repository, either because they claim they cannot afford it or because they forgot to include the costs of preservation when preparing their grant application, or because they are reluctant to make it available to others (maybe either through fear of intellectual property theft or simply embarrassment), or simply because they leave it to the end of the project or even beyond and never get round to it. The ADS has endeavored to simplify the data deposition process by developing a semiautomated file upload system, ADS-Easy (Moore et al. Reference Moore, Hardman, Xia, Richards, Graeme Earl, Sly, Chrysanthi, Murrieta-Flores, Papadopoulos, Romanowska and Wheatley2013). This automates many of the time-consuming processes formerly carried out by its digital archivists and ensures the collection of adequate metadata using standard templates, thereby qualifying depositors for discounted deposit charges. However, it is clear that many archaeologists still find the process difficult and prefer ADS to undertake the work on their behalf, following what tDAR describe as their “full-service model” (McManamon Reference McManamon, Kintigh, Ellison and Brin2017).

While there are many supposed “carrots” that should encourage archaeologists to make their data available, including professional esteem and citation and feedback from others, it is clear that “sticks” are far more effective. When funding bodies make it a requirement that digital data are archived in a trusted repository and made freely available, and will not give out future funding until compliance is demonstrated, the most powerful incentive is provided. In the United Kingdom, the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) has adopted the most robust position, requiring research organizations to publish online appropriately structured metadata describing the research data they hold, normally within 12 months of the data being generated, and for the data themselves to be made available without restriction for a minimum of 10 years (EPSRC 2016). This has led to a flurry of universities establishing their own institutional repositories and requiring researchers to develop data management plans. However, the effectiveness of the policy will still depend upon how far compliance is monitored, policed, and audited. The Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC)—the funding body that funds most university-based archaeological research in the United Kingdom—has adopted a similar, but slightly more conservative, position. Under AHRC funding, rules state that digital resources must be maintained for “a minimum of three years after the end of project funding … but in many, if not most, cases a longer period will be appropriate” (AHRC 2016:66). Historic England, the lead state agency for heritage protection in England, has adopted a robust position to make sure that the digital outputs from the work it funds are adequately archived. Under their funding guidance, all projects are asked “to ensure that digital archives are deposited with the Archaeology Data Service (ADS) (http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/) or a similar recognized digital archiving organization approved by Historic England (HE)” (Historic England 2016:14).

SO IS IT WORTH IT?

It is clear that data preservation does not come cheap. However, data collection is much more expensive. Primary fieldwork tends to be a major cost for any archaeological research but, even when a project seeks to draw upon and synthesize existing data, the cost of collecting and cleaning that data can be prohibitively expensive. The relative inaccessibility of gray literature, now being addressed, is a major contributor to that. In attempting to write a synthesis of recent work in British and Irish prehistory, Richard Bradley (Reference Bradley2007) spent three person-years in data collection from HER offices. In my own research on the Viking and Anglo-Saxon Landscape and Economy (VASLE), using Portable Antiquities Scheme data for metal-detected finds, two person-years of a three-year project had to be spent in data cleaning (Naylor and Richards Reference Naylor and Richards2005). Most recently, in Michael Fulford's Roman Rural Settlement project (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Blick, Brindle, Evans, Fulford, Holbrook, Richards and Smith2015), six person-years have been spent in data collection.

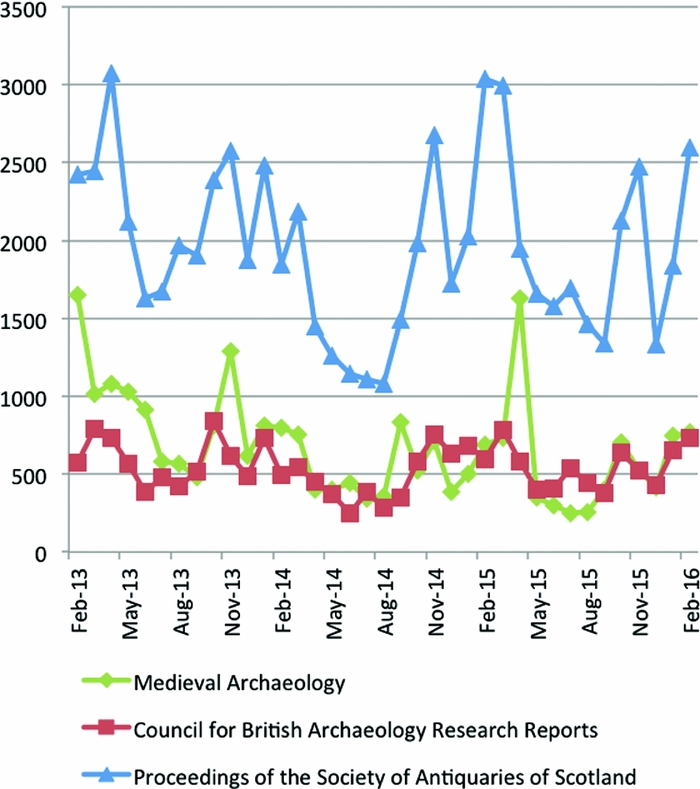

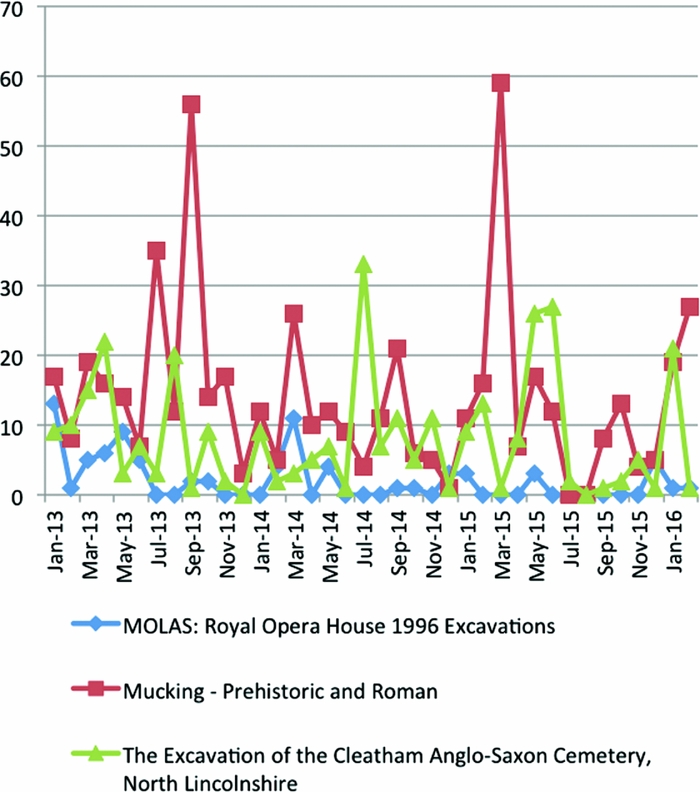

However, if the data produced by such projects are now properly archived and made available for others to use, a huge amount of future effort can be avoided, as well as new research questions made possible (see, for example, Kintigh et al. Reference Kintigh, Altschul, Kinzig, Limp, Michener, Sabloff, Hackett, Kohler and Ludäscher2015). Every ADS archive has a web page that shows the number of archive views and downloads, generally in large numbers. It should also be noted that unlike publications and data in many disciplines (particularly the sciences), most archaeological data does not age. A report or dataset published last century may be just as important today as it was then. Thus, the value of the ADS repository increases with time, particularly as more resources are added, leading to a critical mass of data for some topics. Undoubtedly, the highest levels of use of the ADS come from those simply seeking something to read—whether gray literature reports or back-runs of journal articles (Figure 1). These figures alone justify the resources required to make the reports and articles available Open Access. By comparison, while still substantial, the figures for the reuse of data are much lower (Figure 2). This should not be surprising; the effort and skills involved in downloading a raw data file, understanding the metadata, and opening it up on one's own computer should not be underestimated. Although we have little qualitative data to set besides the quantitative download statistics, it is reasonable to assume that, in order to invest this much effort, the user must have a specific research project in mind. Hence, the research value added from reusing a data file may be significantly greater than that from reading an existing report.

FIGURE 1. Download figures for three sample archaeological journal back-runs, archived by the ADS, February 2013–February 2016.

FIGURE 2. Download figures for three sample archaeological projects, archived by the ADS, February 2013–February 2016.

The use of DOIs is not yet well enough established to undertake citation analysis of those referencing ADS archives in their bibliographies, so evidence for reuse often still relies on anecdotal evidence. In my own university, recent examples include a doctoral study of the Mesolithic in Northern England that made extensive use of unpublished fieldwork reports held by ADS; for example (Blinkhorn Reference Blinkhorn2012); another PhD thesis on Anglo-Saxon monetization reused the artifact database collected for the VASLE project, referred to above (Abramson Reference Abramson2017); an externally funded research project developing techniques for image recognition reused ADS image databases of flint tools and Viking brooches (Power et al. Reference Power, Lewis, Petrie, Green, Richards, Eramian, Chan, Walia, Sijaranamual and De Rijke2017). Similarly, the data provided by the Roman Rural Settlement project has already been reused by a study of Roman brooches (Cool and Baxter Reference Cool and Baxter2016).

Nonetheless, it is clear that archaeologists appreciate the value of discipline-based repositories. A comparative study of data reuse across a range of disciplines commissioned by the JISC (Joint Information Systems Committee) and the Research Information Network (RIN 2011) found that of the archaeologists surveyed about the impact of the ADS on their work:

-

• 84% said ADS had an impact on data sharing

-

• 79% said ADS reduced the time required for data access and processing

-

• 51% said ADS provided new intellectual opportunities

-

• 56% said ADS permitted new types of research

-

• 94% said the data held by ADS were very or quite important for their research

When compared with other repositories, covering domains ranging from atmospheric research to the social sciences, the impact of the ADS emerged very favorably (Table 2).

TABLE 2. Impact on Culture of Data Sharing, by Subject Data Center (after RIN 2011:Figure 16).

Source: Technopolis ranking based on survey of data center users, January 2010.

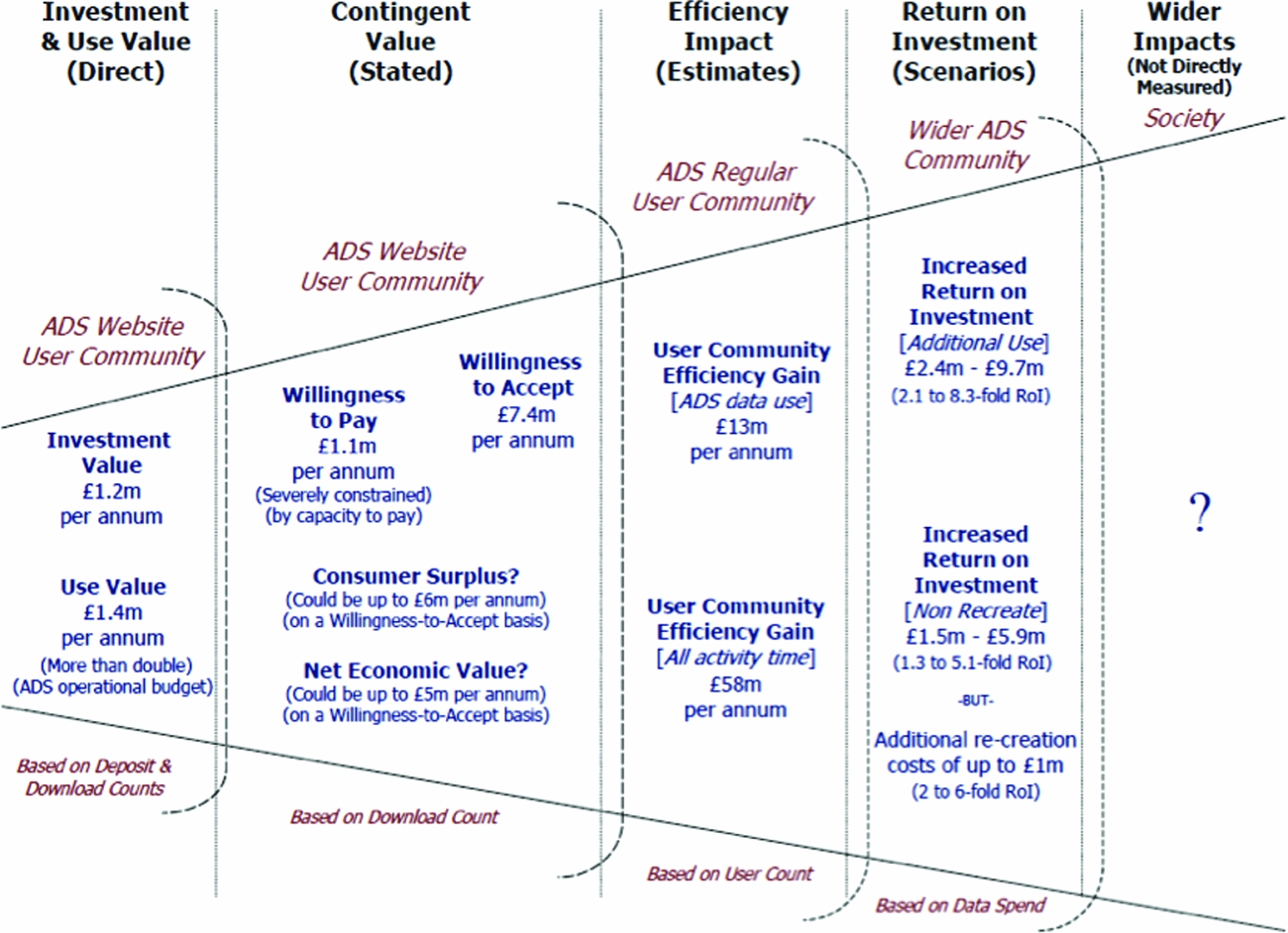

In 2013, JISC commissioned an independent study to analyze and survey perceptions of the value of digital collections held by the ADS and to measure, assess, and quantify the economic impact of those collections. The work was undertaken by Neil Beagrie, a digital preservation specialist, and John Haughton, a strategic economist who specializes in using standard economic procedures to try to assign a value to things that are not usually measured. While such procedures are routine in the public sector—for example, in assessing the cost-benefit of a new road or rail infrastructure—they are rarely employed in the cultural sector, but may become increasingly important in persuading funding bodies of the economic impact of the heritage sector. Beagrie and Houghton explored a range of methods and sources, including data from 1996–2011, on the growth of collections and users at ADS and how return on investment grows with the collections (Beagrie and Houghton Reference Beagrie and Houghton2013). Their quantitative analysis suggests that the economic benefits of ADS substantially exceed the operational costs. However, when users were asked what they would be willing to pay for access to ADS, the total came to only £1.1 million per annum, probably reflecting the relative low level of funding in the sector, as well as the attitude that access to data should be free at the point of use. When the question was turned around, and users were asked how much they would need to be compensated if access to ADS was taken away, the total came instead to £7.4 million per annum. In addition, a very significant increase in research efficiency was reported by users as a result of using the ADS, which was calculated to be worth at least £13 million per annum—five times the costs of operation, data deposit, and use (Figure 3). They also identified a potential increase in return on investment in data creation/collection resulting from the additional use that was facilitated by ADS that may be worth between £2.4 million and £9.7 million per annum over 30 years in net present value from one year's investment—a two-fold to eight-fold return on investment. Due to the conservative treatment of use and user statistics, the value estimates presented are likely to be conservative. Although Beagrie and Houghton did not directly measure the wider impacts of ADS on society as a whole, the returns on investment provide a window on those impacts.

FIGURE 3. The economic value and impacts of the ADS. Source: Beagrie and Houghton Reference Beagrie and Houghton2013: Figure 1.

JOINING IT ALL UP

Many countries have now recognized the value of developing their own digital repositories for archaeological data. In addition to the ADS in the United Kingdom and tDAR in the United States, there are national repositories in the Netherlands (Gilissen Reference Gilissen2013; Hollander Reference Hollander2013), Sweden (Jakobsson Reference Jakobsson2013), and Germany (Schäfer and Trognitz Reference Schäfer and Trognitz2013), and another being established in Austria. However, there is inevitably a tension in bringing resources together in single repositories. On the one hand, trusted digital repositories need to reach a critical mass if they are to maintain the staffing levels and range of skills required to achieve sustainability. They also need to have organizational backing and long-term commitment, and, if their resources are also to be “trusted” in the more conventional sense, then some reputable institutional imprint is essential. On the other hand, as Huggett (Reference Huggett2016) has identified, there is a risk that we are simply creating a new set of data silos that challenge the founding principles of a distributed Internet. In fact, digital repositories need to do both: they must bring resources together and make it easy for users to interrogate them via shared and user-friendly interfaces; but they must also open data up via APIs, harvesting protocols such as OAI-PMH and Linked Open Data (LOD) so that the data can be viewed and manipulated via multiple routes (May et al. Reference May, Binding and Tudhope2015). The ADS has undertaken some LOD experiments linking excavation database records to fieldwork text reports as part of the STELLAR project. There is also a growing community participating in LOD in archaeology, including services such as Pleiades (a community-built gazetteer of ancient places), Pelagios (also joining up places in the Classical world), and Open Context (the web-based system for publishing archaeological data), some of which are demonstrating research results. Opening up data in this totally permissive sense can sometime be at odds with the more conventional gatekeeper role of national heritage bodies and can create internal tensions. Yet there are good reasons for managing domain-based repositories at the national level. This both gives them an appropriate scale and also tends to coincide with legislative remits and heritage protection policies, as well as the scope of most funding streams.

Nonetheless, archaeological research questions rarely coincide with modern political boundaries, which were irrelevant for the vast majority of the timespan of the human past. As early as 1992, Henrik Jarl Hansen (Reference Hansen, Andresen, Madsen and Scollar1992) expressed the need to join up digital resources across Europe, and the European Commission has been a key funding agency that has facilitated several projects in this area. In 2002–2004, the ADS led a consortium of European partners on the EU-funded ARENA project (Kenny and Richards Reference Kenny and Richards2005). One of the outcomes of the project was a portal that provided a distributed cross-search of sites and monuments records for six countries (Dam et al. Reference Dam, Austin, Kenny, Niccolucci and Hermon2010). However, this relied upon dated technologies such as Z39.50, which had been developed for cross-searching library catalogues. In 2009–2010, the ADS was able to work with DANS to migrate the ARENA portal into a more flexible web services architecture. A similar technological infrastructure was also employed in a collaborative project between the ADS and tDAR to build a Transatlantic Archaeological Gateway (TAG) (Jeffrey et al. Reference Jeffrey, Xia, Richards, Bateman, Kintigh, Pierce-McManamon, Brin, Zhou, Romanowska, Wu, Xu and Verhagen2012). Subsequently, the ADS has played a significant role in the ARIADNE e-infrastructure (Aloia et al. Reference Aloia, Binding, Cuy, Doerr, Fanini, Felicetti, Fihn, Gavrilis, Geser, Hollander, Meghini, Niccolucci, Nurra, Papatheodorou, Richards, Ronzino, Scopigno, Theodoridou, Tudhope, Vlachidis and Wright2017; Niccolucci and Richards Reference Niccolucci and Richards2013), which has developed a powerful cross-search portal, as well as experiments in Linked Open Data. To achieve interoperability across different European languages and cultures is challenging, and adherence to data standards is essential for any level of semantic interoperability and cross-search. In ARIADNE, national subject terms have been mapped to a common core standard (in this case, the Getty Art and Architecture Thesaurus) and archaeological period terms have been defined according to explicit criteria, working with the North American PeriodO initiative (Shaw et al. Reference Shaw, Rabinowitz, Golden and Kansa2015). As always, there are challenges in turning projects into services, but by linking ARIADNE to the ESFRI roadmap (ESFRI 2016) via the preparatory phase for a new infrastructure dedicated to Heritage Science (E-RIHS), it is anticipated that ARIADNE can achieve sustainability.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

In summary, this paper has attempted to demonstrate that, while digital preservation has a cost, data collection—and data loss—is much more expensive. If we make digital data easily available, then they are reused, and a number of studies have shown both a research and an economic return on that investment. While the greatest demand is for simple text reports, especially the gray literature, we should also explore the potential offered by new models for data publication and dissemination. Underpinning our digital preservation work is fundamental work on data standards and, for this to facilitate interoperability and Big Data projects, it is essential that digital archives collaborate at an international level. The experience of ADS over the last 20 years has demonstrated that, while it takes time, it is possible to develop a sustainable business model for a self-sufficient national digital repository for archaeology.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets referred to in this paper are available under an open license from the Archaeology Data Service using the DOI provided in the bibliography.