Introduction

Antarctic and Southern Ocean (ASO) science is multidisciplinary, spanning the natural, physical and social sciences (see Reference Kennicutt, Liggett, Havermans and BadheKennicutt et al. n.d.). However, the geosciences predominate for a range of historical and practical reasons. This is noteworthy because the geosciences are the least diverse of all Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) fields. For example, 86% of all PhDs in geosciences (including ocean, atmospheric and earth sciences) in the USA since 1973 have been awarded to white people (Bernard & Cooperdock Reference Bernard and Cooperdock2018) and men outnumber women (see Handley et al. Reference Handley, Hillman, Finch, Ubide, Kachovich and McLaren2020).

The homogeneity of the geosciences has had a lasting effect on the social identities of scientists and their experiences of remote fieldwork in Antarctica and elsewhere (see Núñez et al. Reference Núñez, Rivera and Hallmark2020). For example, there is a growing body of research showing that underrepresented groups (women, LGBTIQ+, people of colour, etc.) find geosciences fieldwork fraught with excessive barriers (physical, social, economic) limiting their participation (e.g. Clancy et al. Reference Clancy, Nelson, Rutherford and Hinde2014). Moreover, issues associated with harassment in the geosciences are now well documented (e.g. Wadman Reference Wadman2019).

The androcentric, colonialist and sexist underpinnings of geoscientific fieldwork have had a significant effect on contemporary fieldwork practices in ASO science and many other scientific fields (e.g. anthropology, archaeology) (Collis Reference Collis2009, Church Reference Church2013). Fieldwork as a practice originates in Earth science and, from its earliest beginnings, it was defined by the individual heroic efforts of white, heterosexual, upper-class men (for an overview, see Church Reference Church2013). The first ‘scientists’ were ‘gentlemen scholars’ or persons of ‘independent means’ who explored the natural world and shared findings with their (male) ‘peers’ (Church Reference Church2013, p. 184). Traditions of fieldwork in Antarctica and elsewhere were institutionalized by European and North American naval and overland ‘frontier’ exploration in the late eighteenth century (Church Reference Church2013). Although there were (upper-class) women working as scientists in Europe during this time, they were largely precluded from leading their own independent research programmes. Women mainly did local fieldwork where their high social standing was protected, and often in partnership with men (husbands, brothers, etc.) (Burek & Kölbl-Ebert Reference Burek and Kölbl-Ebert2007).

Women were excluded from exploratory and scientific Antarctic expeditions, and in the first half of the twentieth century they mainly travelled ‘South’ as wives and partners (Collis Reference Collis2009). Many polar institutes justified the exclusion of women by arguing that there were no facilities for them on stations (see Seag Reference Seag2017). The Australian Antarctic Division and the British Antarctic Survey only allowed women to stay on research stations and conduct land-based Antarctic fieldwork starting in the late 1970s and early 1980s, respectively. Even when women were included in Antarctic exploration, it remained an affair mainly for white people (van der Watt & Swart Reference van der Watt, Swart, Roberts, van der Watt and Howkins2016).

Most of the limited research on the lived experiences of remote fieldwork in STEM focuses on cisgender (white) women (Bracken & Mawdsley Reference Bracken and Mawdsley2004). For example, women often have difficulty going to the toilet privately in remote field camps, which can make them more vulnerable to harm (Nash et al. Reference Nash, Nielsen, Shaw, King, Lea and Bax2019). Feminist scholars also highlight that fieldwork cultures often emphasize hypermasculinity through heavy drinking, jokes and other exclusionary practices (Hanson & Richards Reference Hanson and Richards2019). McCahey (Reference McCahey2021, p. 17) argues that pornography has been a staple of Antarctic station culture, effectively constructing the field as ‘masculine’ and ‘unfit for women’. As a result, women are 3.5 times more likely to experience sexual harassment during remote scientific fieldwork compared to men (Clancy et al. Reference Clancy, Nelson, Rutherford and Hinde2014).

A recent study of gendered barriers in ASO fieldwork in the Australian Antarctic Program confirms this: 60% of women surveyed had been sexually harassed at some point during their career and 50% never reported their abuse (Nash et al. Reference Nash, Nielsen, Shaw, King, Lea and Bax2019). Women who do ASO fieldwork rarely report sexual harassment (Nash et al. Reference Nash, Nielsen, Shaw, King, Lea and Bax2019) because working in small teams in remote stations or field camps can make it difficult to report incidences or to leave the situation (Wadman Reference Wadman2017). Women also hesitate to complain because it can exclude them from subsequent fieldwork, ending an Antarctic science career.

Scholars in a variety of disciplines over several decades have noted the lack of organizational attention paid to safety and training regarding sexual harassment in remote scientific fieldwork (e.g. St John et al. Reference St John, Riggs and Mogk2016, Marín-Spiotta et al. Reference Marín-Spiotta, Barnes, Berhe, Hastings, Mattheis and Schneider2020). Like many other disciplines, fieldwork has been a cornerstone in the geosciences and an important rite of passage that ‘makes’ a scientist (Kloß Reference Kloß2017). #MeToo, however, is arguably forcing scientists and institutions globally to reckon with fieldwork sexual harassment (Nash & Nielsen Reference Nash and Nielsen2020). ASO science had to do this in 2017 when Dr Jane Willenbring (a US geoscientist) revealed appalling sexual harassment by Professor David Marchant when he was supervising her Antarctic fieldwork as a PhD student in the 1990s. Willenbring waited 17 years to make a complaint (until she was tenured) because she feared Marchant would ruin her career. Following an 18 month investigation, in April 2019, Boston University terminated Marchant's employment (Wadman Reference Wadman2019).

The heightened visibility of sexual harassment in the geosciences has prompted a wider focus on organizational power structures and identity politics in STEM broadly and ASO science specifically (see Nash & Nielsen Reference Nash and Nielsen2020). For example, large scientific societies including the American Geophysical Union and National Antarctic Programs (NAPs) such as the Brazilian Antarctic Program (PROANTAR) and the United States Antarctic Program are re-examining their roles and policies in relation to sexual harassment, including more robust procedures for reporting abuse in recent years (see Williams et al. Reference Williams, McEntee, Hanson and Townsend2017, Barros-Delben et al. Reference Barros-Delben, Moraes Cruz, de Melo Cardoso and Arnoldus de Wit2021, National Science Foundation 2021). Current efforts to broaden participation in the geosciences globally are also now centred on addressing sexual harassment (e.g. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), Geoscience Australia) and increasing inclusion and equity (see Núñez et al. Reference Núñez, Rivera and Hallmark2020).

The issue of fieldwork sexual harassment is complex and involves many institutional stakeholders, legal frameworks and processes internationally. This study focuses on basic steps in sexual harassment prevention by NAPs, whose role in the issue of fieldwork sexual harassment has not yet been explored in the literature. NAPs manage Antarctic science and policy activities in 30 countries that are Antarctic Treaty signatories. Thus, NAPs are a critical site for research on this topic because they are entrusted with national leadership in ASO science (COMNAP 2021).

Of the very limited research on fieldwork sexual harassment, most studies have focused on individual perceptions (e.g. Burns Reference Burns2000, Nash et al. Reference Nash, Nielsen, Shaw, King, Lea and Bax2019). Therefore, there is an urgent need for research on organizational approaches and policies regarding fieldwork sexual harassment from bodies such as NAPs. This is an important step because the historical silences surrounding sexual harassment in Antarctica have obscured the ways in which the field is structured by patriarchy and legacies of sexism and inequality (Nash & Nielsen Reference Nash and Nielsen2020). The purpose of this study is, therefore, to assess the current availability and quality of fieldwork sexual harassment policies in NAPs. In doing so, it provides important starting points for conversations about accountability as well as recommendations to initiate change.

Workplace sexual harassment definitions, predictors and outcomes

Sexual and gender harassment are common experiences for people in underrepresented groups working in male-dominated fields such as STEM (NASEM 2018). Women, for example, are often the primary targets of harassing behaviour. However, people with multiple marginalized identities (e.g. women of colour, LGBTIQ+) experience sexual harassment at greater rates in STEM broadly (Clancy et al. Reference Clancy, Lee, Rodgers and Richey2017).

Sexual or ‘sex-based’ harassment is an umbrella term that refers to ‘behavior that derogates, demeans, or humiliates an individual based on that individual’s sex‘ (Berdahl Reference Berdahl2007, p. 644). Fitzgerald’s Tripartite Model comprises three categories of harassing behaviour, including unwanted sexual attention, sexual coercion and gender harassment (Fitzgerald et al. Reference Fitzgerald, Gelfand and Drasgow1995). Unwanted sexual attention ‘involves expressions of romantic or sexual interest that are unwelcome, unreciprocated, and offensive to the recipient’ (e.g. touching) (Leskinen et al. Reference Leskinen, Cortina and Kabat2011, p. 26). Sexual coercion is a ‘specific, severe, rare form of unwanted sexual attention, involving similar sexual advances coupled with bribery or threats to force acquiescence’ (e.g. employment is contingent on meeting sexual demands) (Lim & Cortina Reference Lim and Cortina2005, p. 484). In contrast, gender harassment ‘communicates hostility that is devoid of sexual interest’, such as name-calling and insults (e.g. ‘Women don’t belong in STEM') (Leskinen et al. Reference Leskinen, Cortina and Kabat2011, p. 26).

Gender harassment is the most common type of workplace sexual harassment in STEM (NASEM 2018, p. 42). Sexual coercion, in comparison, is relatively rare. Therefore, the term ‘sexual harassment’ is a misnomer; harassment is less often about sex and more often about disrespect - a ‘put down’ vs a ‘come on’ (Clancy et al. Reference Clancy, Cortina and Kirkland2020). However, because gender harassment lacks an explicit sexual component, it is less visible and has been undertheorized and neglected in organizational harassment policies (Leskinen et al. Reference Leskinen, Cortina and Kabat2011). Cortina's iceberg analogy for harassment is apt in that it shows that only a slice of sexual harassment (such as sexual assault) rises into public consciousness (see Fig. 1; NASEM 2018, Cortina & Areguin Reference Cortina and Areguin2020). The rest of the iceberg is buried deep but includes more common and insidious gender harassment such as name-calling (NASEM 2018). In this way, many organizational policies are flawed because they do not engage with gender harassment (Cortina & Areguin Reference Cortina and Areguin2020).

Fig. 1. The harassment iceberg (NASEM 2018, https://www.nap.edu/visualizations/sexual-harassment-iceberg/).

It is important to note that much of the sexual harassment scholarship derives from the Anglosphere and, specifically, the USA (e.g. Buchanan et al. Reference Buchanan, Settles, Hall and O'Connor2014, NASEM 2018, Cortina & Areguin Reference Cortina and Areguin2020). This is a result of the hyper-dominance of English in international science communication and publication. Scholarship in languages that are seen as marginal in science are less accessible (e.g. less often published in highly cited journals or indexed in the main citation indexes). Thus, an important consideration is that definitions of sexual harassment can vary widely by national culture (see Mishra & Davison Reference Mishra and Davison2020), but there is much less available research focusing on these differences. For example, Pryor et al. (Reference Pryor, DeSouza, Fitness, Hutz, Kumpf and Lubbert1997) found that North American, Australian and German students perceived hostile work environment situations more in terms of power abuse and gender discrimination, whereas Brazilian students perceived the same scenarios as innocuous sexual behaviour but not sexual harassment. Similarly, research suggests collectivist cultures that stress the importance of belonging and the needs of the group (Kennedy & Gonzalka Reference Kennedy and Gonzalka2002) and cultures premised on traditional masculine ideals may be more tolerant of workplace sexual harassment (Merkin Reference Merkin2012). These types of national cultural differences have implications for how organizations approach the issue (Mishra & Davison Reference Mishra and Davison2020).

Nevertheless, a large body of research from the Anglosphere confirms that organizational climate (how employees perceive their working environment) is a strong predictor of sexual and gender harassment frequency (Buchanan et al. Reference Buchanan, Settles, Hall and O'Connor2014, p. 688). As Buchanan et al. (Reference Buchanan, Settles, Hall and O'Connor2014, p. 688) suggest, a positive organizational climate increases workplace well-being and decreases retaliation against those who report harassment. Another predictive factor for organizational sexual harassment is ‘job gender context‘ - the proportion of men and women in the workplace (Fitzgerald et al. Reference Fitzgerald, Magley, Drasgow and Waldo1999). For instance, in male-dominated workplaces (e.g. police, military, STEM organizations), harassment is more likely to occur (Aycock et al. Reference Aycock, Hazari, Brewe, Clancy, Hodapp and Goertzen2019). A final predictive factor for sexual harassment frequency is organizational tolerance for harassment (Buchanan et al. Reference Buchanan, Settles, Hall and O'Connor2014). When leaders model harassing behaviours, penalize employees for reporting harassment or neglect to sanction harassers, sexual harassment increases. Similarly, in these contexts, people ‘… who deviate the most from conventional heterosexual masculinity (e.g. women, gay men, anyone perceived to be feminine) receive the worst treatment’ (Cortina & Areguin Reference Cortina and Areguin2020, p. 296).

The bulk of the research on the harms associated with workplace sexual harassment focuses on women in the industrialized West. This literature shows that women often interpret a wider range of behaviours as ‘harassment’ compared to men (e.g. Rotundo et al. Reference Rotundo, Nguyen and Sackett2001). Workplace sexual harassment significantly reduces women's psychological well-being and productivity (for comprehensive overviews of outcomes, see Sojo et al. Reference Sojo, Wood and Genat2016, NASEM 2018, Cortina & Areguin Reference Cortina and Areguin2020). In STEM fields in the USA, frequent workplace sexual harassment can force women to leave their jobs or their careers altogether, resulting in a loss of science talent and organizational knowledge (NASEM 2018). Gender harassment is equally as detrimental to women's physical, psychological and emotional health as sexual coercion or unwanted sexual attention (Leskinen et al. Reference Leskinen, Cortina and Kabat2011). The literature also shows that the impact of workplace harassment on women may include posttraumatic stress (Ho et al. Reference Ho, Dinh, Bellefontaine and Irving2012), misuse of alcohol (Rospenda et al. Reference Rospenda, Richman and Shannon2006) and symptoms of depression (Reed et al. Reference Reed, Collinsworth, Lawson and Fitzgerald2016).

Although men and gender non-binary people do experience sexual harassment, there is a dearth of research on the experiences of people in these groups. For instance, when men are harassed, it is often because they are perceived to not be conforming to heterosexual masculinity (Clancy et al. Reference Clancy, Cortina and Kirkland2020, see also Berdahl Reference Berdahl2007). The research on outcomes of sexual harassment for men is also less conclusive (Cortina & Areguin Reference Cortina and Areguin2020). Some studies suggest that men suffer equally to women in terms of impaired physical, psychological and emotional well-being (e.g. Bergman & Henning Reference Bergman and Henning2008). Other studies suggest that women suffer more than men, particularly in terms of outcomes such as problem drinking (e.g. Freels et al. Reference Freels, Richman and Rospenda2005).

Studies have also shown that men are at greater risk of depression because of sexual harassment compared to women (e.g. Vogt et al. Reference Vogt, Pless, King and King2005). As Cortina & Areguin (Reference Cortina and Areguin2020, p. 294) observe, while the literature on harms to men vs women is mixed, the point is that both women and men suffer from workplace sexual harassment, and disparities in the research may result from the way that men and women are harassed, as well as other factors involved in why they are being harassed.

There is now an emerging body of research focusing on intersectional sexual harassment in STEM fields. Intersectionality is a well-established social sciences framework for examining complex, intersecting systems of power and oppression and how they shape experiences and opportunities (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1989). Grounded in the research and activism of women of colour (Carbado et al. Reference Carbado, Crenshaw, Mays and Tomlinson2013), intersectionality allows us to look more deeply at questions of exclusion. Specifically, intersectionality facilitates the examination of individual and group lived experiences within larger social, historical, political, environmental and economic contexts (Metcalf et al. Reference Metcalf, Russell and Hill2018). For instance, we do know that women of colour in STEM are more frequently harassed than other groups and experience a ‘double whammy of discrimination’ (Berdahl & Moore Reference Berdahl and Moore2006, p. 427) based on gender and racial stereotypes (see also Clancy et al. Reference Clancy, Lee, Rodgers and Richey2017, Reference Clancy, Cortina and Kirkland2020, Moore & Nash Reference Moore and Nash2021). Similarly, gender diverse/non-conforming people in STEM experience more homophobic and transphobic remarks than cisgender women and are also more likely to feel unsafe at work and experience verbal harassment (Richey et al. Reference Richey, Lee, Rodgers and Clancy2019). A recent study of 25 000 US STEM professionals confirms that LGBTQ scientists are 30% more likely to be harassed at work compared to their non-LGBTQ peers (Cech & Waidzunas Reference Cech and Waidzunas2021). Harassment is especially compounded for LGBTQ scientists of colour (Cech & Waidzunas Reference Cech and Waidzunas2021). There is an urgent need for more research focusing on intersectional understandings of workplace harassment (for an overview, see Cortina & Areguin Reference Cortina and Areguin2020).

Policy and prevention

Given the harms associated with workplace sexual harassment for multiple social groups, it is essential that organizations have effective and accessible policies in place to protect employees and the organization. When institutional policies and procedures are missing, this can create a permissive environment for sexual harassment in which responsibility for managing these issues instead falls to individual employees (see Fusilier & Penrod Reference Fusilier and Penrod2015). There is a large body of literature focusing on crafting effective sexual harassment policies (e.g. Paludi & Paludi Reference Paludi, Paludi, Paludi and Paludi2003). While an in-depth discussion of this is beyond the scope of this article, I will summarize some of the defining features of an effective sexual harassment policy here. These include a clear statement that harassment is not tolerated (Buchanan et al. Reference Buchanan, Settles, Hall and O'Connor2014); different types of sexual harassment are defined (e.g. gender harassment vs sexual coercion) (Australian Human Rights Commission 2021); the policy is disseminated to all employees (Paludi & Paludi Reference Paludi, Paludi, Paludi and Paludi2003); and the policy is highly visible to employees and the public to increase exposure (e.g. placed in handbooks, on the intranet/internet) (Australian Human Rights Commission 2021).

Online availability is especially important in the context of NAPs because they are trusted centres of scientific knowledge with many stakeholders (see Fusilier & Penrod Reference Fusilier and Penrod2015). It is essential that governments, institutions and prospective/current/past employees can easily access the policy. The public availability of a policy also sends a clear message about organizational intolerance for harassment. The US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) also recommends that harassment policies point to multiple formal and informal pathways for employees to make a complaint (EEOC 2012), including reporting anonymously and to a variety of people (Paludi & Paludi Reference Paludi, Paludi, Paludi and Paludi2003). Moreover, when complaints are made, they must be dealt with promptly and remedied with corrective action (Buchanan et al. Reference Buchanan, Settles, Hall and O'Connor2014).

In general, organizations rely on individual victim-survivors of sexual harassment to report their abuse formally in order to make it visible in the organization. However, the literature shows that reporting can increase psychological stress by asking victim-survivors to relive their trauma perhaps multiple times to different people and raise the potential for organizational retaliation against the victim, especially if their identities are not protected (Cortina & Areguin Reference Cortina and Areguin2020). For example, the women in Nash et al.'s (Reference Nash, Nielsen, Shaw, King, Lea and Bax2019) study of experiences of Australian Antarctic fieldwork made it apparent in their open-ended survey comments that the onus is on women to make a complaint and that there is unacknowledged emotional labour associated with having to determine whether a complaint is justified. Thus, it is unsurprising that victims of workplace harassment rarely make formal complaints. The NASEM (2018) report shows that sexual harassment reporting in STEM is very low and is seen as a last resort.

Method

Sample

In December 2020, I conducted a desktop analysis of 36 NAP websites with a focus on the availability of expeditioner handbooks/field manuals and sexual harassment policies. I used the comprehensive list of NAPs on the Council of Managers of National Antarctic Programs (COMNAP) website (www.comnap.aq/our-members) to determine the 36 websites to access in this study. Thirty NAPs are signatories of the Antarctic Treaty and Environmental Protocol, making them full NAP members (e.g. Australia, UK, India) (COMNAP 2021). The other six are Observer NAPs (e.g. Canada, Turkey, Switzerland) (COMNAP 2021). Sexual harassment was chosen for study because it is a pervasive issue in STEM (NASEM 2018) and in Antarctic fieldwork specifically (see Nash et al. Reference Nash, Nielsen, Shaw, King, Lea and Bax2019, Nash & Nielsen Reference Nash and Nielsen2020, Barros-Delbens Reference Barros-Delben, Moraes Cruz, de Melo Cardoso and Arnoldus de Wit2021). It also allows for a relatively objective evaluation of how NAPs are managing safety and well-being in a #MeToo era (e.g. the expeditioner handbook and/or field manual and related policies are present or absent). NAPs were chosen for the sample because they presumably have strong interests in safeguarding the health and safety of expeditioners. Key research questions included:

1) Are expeditioner handbooks/field manuals publicly available online?

2) Do expeditioner handbooks/field manuals mention sexual harassment?

3) Do expeditioner handbooks/field manuals outline available sexual harassment complaint procedures?

Search procedure

An Antarctic expeditioner handbook and/or field manual is commonly produced in a portable document format (pdf) and/or as a series of webpages that provide an expeditioner with background information about the relevant NAP, what one can expect when working in Antarctica, what to bring, how to survive and how to behave. The length of these resources is highly variable. For example, the Uruguayan expeditioner handbook is 11 pages, whereas the Swedish and US handbooks are 305 and 146 pages, respectively. A sexual harassment policy typically discusses an organization‘s prohibitions against this form of harassment as well as the procedure for making a complaint. My initial assumption in this study was that harassment policies would be outlined in expeditioner handbooks and/or field manuals. Antarctic expeditioner handbooks/field manuals were obtained by doing a Google search such as ’[name of NAP] expeditioner handbook‘ or ’field manual'. If that approach did not produce the desired result, the search option on the relevant NAP website was used to search terms such as ‘fieldwork’ and ‘sexual harassment’. If necessary, human resources web pages were examined for links to the handbook and/or any relevant code of conduct or sexual harassment policy. In most cases, none of this information could be located online. Similarly, where it did exist, information about fieldwork was in a different part of the NAP website from the harassment policy. Six of the 36 the NAP websites were not available in English. As a white English speaker in Australia, I recognize that I am limited to texts written in my native language and that confirm my own knowledge. I generated a basic translation of websites in languages other than English using Google Translate. I also used the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) World Policy Analysis Center (2021) website to access social policy data on the 36 countries with NAPs to see which countries currently have national workplace sexual harassment legislation.

Coding

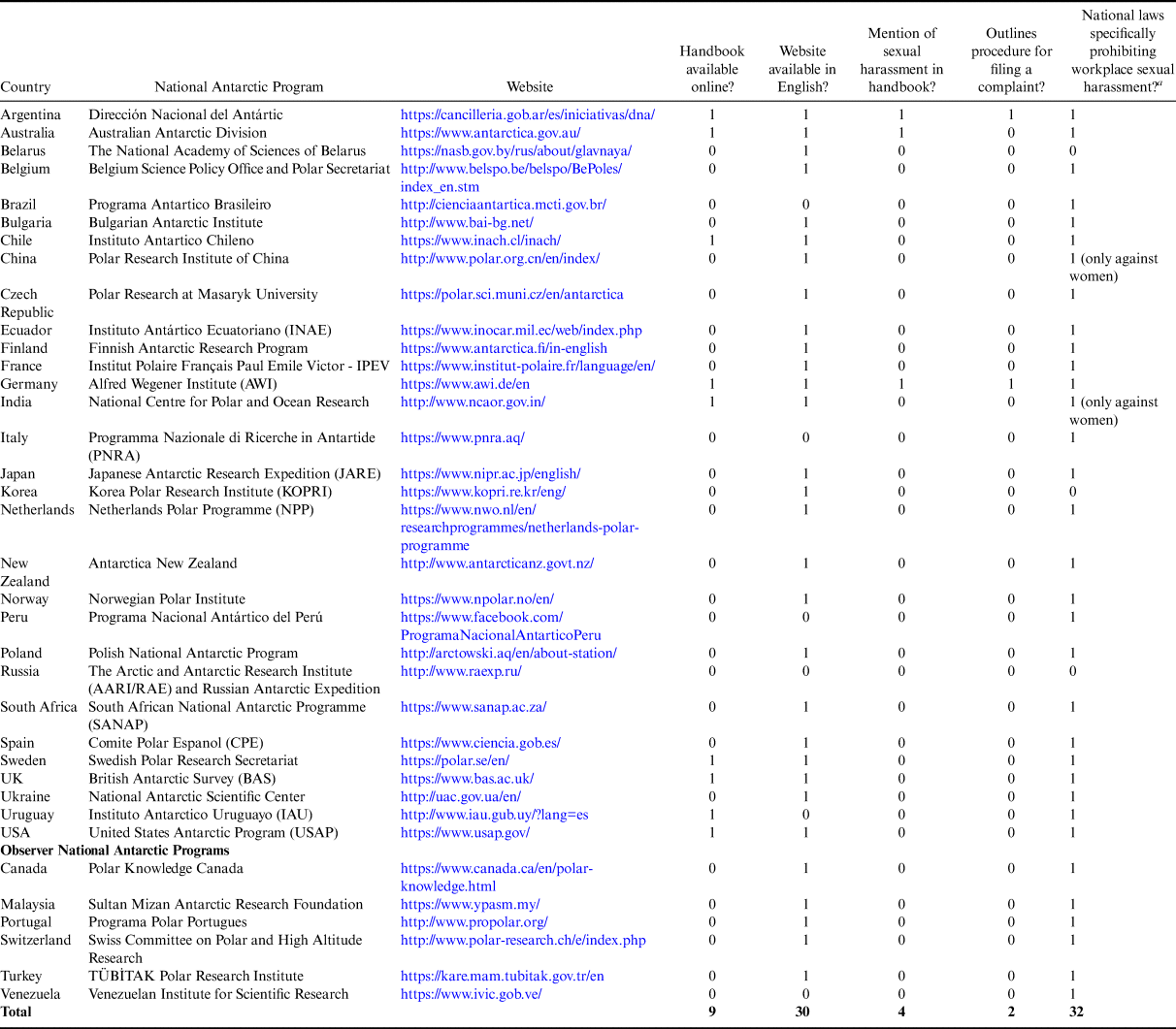

Each available NAP website was coded according to 1) if the expeditioner handbook and/or field manual was available online, 2) if the website was available in English, 3) whether the relevant document mentioned sexual harassment, 4) whether the relevant document outlined how to make a complaint about sexual harassment and 5) if the country has laws prohibiting workplace sexual harassment (see World Policy Analysis Center 2021). Binary codes were assigned ‘1’ for the characteristic's presence and ‘0’ for its absence (see Table I).

Table I. Availability of expeditioner handbooks/field manuals and related mentions of sexual harassment on National Antarctic Program websites.

a Source: World Policy Analysis Center (2021).

Results

Research Question 1: Are expeditioner handbooks/field manuals publicly available online? The data suggest that 25% (n = 9) of the 36 NAPs in this study made their expeditioner handbooks/field manuals available online. The nine available handbooks were from full NAP members (Argentina, Australia, Chile, India, Germany, Sweden, UK, Uruguay, USA). With the exception of Germany, the NAPs provided this information as a downloadable pdf. Germany provided this information in a series of web pages with embedded links. None of the Observer NAPs provided this information online.

Research Question 2: Do expeditioner handbooks/field manuals mention sexual harassment? And Research Question 3: Do expeditioner handbooks/field manuals outline available gender/sexual harassment complaint procedures? Analyses of these questions included only the nine NAPs for which an expeditioner handbook or field manual was available online. Of the nine NAPs, 33% (n = 3) referred to sexual harassment (Argentina, Australia, Germany) in the expeditioner handbook or field manual. These three NAPs refer to sexual harassment and not the subtype of gender harassment (which is statistically much more common). Other NAPs in the UK and USA referred to generalized harassment in separate documents titled ‘Code of Conduct’.

For the most part, NAPs used the expeditioner handbook or field manual to focus on aspects of fieldwork that provide an obvious source of risk and danger. Antarctic expeditioners are primarily trained to think about ‘risk’ and ‘danger’ in the physical environment. For example, the Swedish NAP devotes the entirety of the ‘Safety and Risk Management’ section of the field manual to avoiding physical injury from high-risk activities (e.g. falling in a crevasse, cooking in a tent). The avoidance of alcohol and drugs is the only behavioural standard highlighted in both the Swedish and Chilean manuals in relation to the fact that the use of these substances may prevent one from being able to do one's job, not because there is a well-known link between illicit substances and inappropriate sexual behaviour.

The three NAPs that did mention sexual harassment in their handbooks (Argentina, Australia, Germany) used gender-neutral language to describe it. This language gives the appearance of pertaining to all expeditioners equally. For example:

All personnel will conduct themselves with the proper decorum required to perform functions as part of the Argentine Antarctic Program. All personnel, whatever their function and category, must conduct themselves with respect and courtesy towards all members of the crew, staff deployed in the Antarctic Campaign, and anyone else who is occasionally at the base … The Argentine Foreign Ministry has procedures for situations of workplace or sexual harassment … (Argentina)

All expeditioners have a legal right to work in an environment that is free from harassment and discrimination … Sexual harassment is any unwanted, unsolicited and unreciprocated behaviour of a sexual nature that is objectionable to another individual. Any behaviour or series of behaviours, despite the intention of the individual performing the behaviours, will be considered as sexually harassing if they are experienced that way by the recipient. (Australia)

… Sexual misconduct of any kind is strictly forbidden … Sexual harassment is any unwanted, unsolicited and unreciprocated behavior of a sexual nature. Sexual harassment includes but is not limited to unwelcome sexual advances, unwelcome requests for sexual favors, and other unwanted verbal, nonverbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature. Special work-related cases include those where a person's submission to such conduct is implicitly or explicitly made the basis for employment decisions, academic evaluation, grades or advancement … (Germany)

In relation to Research Question 3, Argentina and Germany were the only NAPs to provide information about how to lodge a sexual harassment complaint. Both programmes describe multiple reporting avenues (e.g. if you do not want to report to a station leader, you can report to another member of staff in the organization).

Any case of harassment must be reported immediately to the Base Chief and, if applicable, to the Chief Scientist, and these in turn to the Dirección Nacional del Antártico (DNA), or the affected person (whether civil or military, national or foreign) may communicate directly with the authorities of the DNA and/or make the complaint directly to the competent authorities … (Argentina)

As a victim, seek immediate help from a person of trust. The Chief Scientist, the Head of Expedition or of Station, or the ship or flight captain must be notified of the incidence. If you don't want to talk to a member of the expedition, you can also contact [A] or [B] from AWI directorate's office, who are in charge of complaints with regards to the General Act on Equal Treatment. (Germany)

In contrast, although the Australian Antarctic Program mentions sexual harassment specifically in its expeditioner handbook, the Program does not have specific text about how to lodge a complaint. Rather, it provides expeditioners with a list of phone numbers (e.g. Polar Medicine, Recruitment) without specific information about which number is appropriate for lodging sexual harassment complaints.

It is notable that none of the expeditioner handbooks or field manuals examined in this study referred to any of the subcategories of sexual harassment such as gender harassment - despite its prevalence. This means that most of the ‘harassment iceberg’ is being ignored (see Fig. 1). Similarly, none of the available handbooks addressed intersectionality - or the interplay between various social identities and harassment (e.g. the experience of workplace sexual harassment for a woman of colour or LGBTIQ+ people).

Discussion

This study provides a window into the current management of sexual harassment in NAPs. This study is unique because the role of organizational policies at the level of NAPs has largely gone unrecognized. Here, I have shown that, with few exceptions, NAPs are not explicitly addressing the issue of sexual harassment in their expeditioner handbooks or field manuals. This is a problem because these documents are more than just a collection of relevant information, policies and procedures - they are essential communication tools that inform the field culture and reflect the values of the NAP.

Importantly, this study provides another source of evidence of the continuation of masculinist, disembodied and neutral epistemological approaches to scientific fieldwork that do not reflect reality. These approaches are untenable because they theorize fieldworkers as invisible and unmarked by social position (e.g. gender, race/ethnicity, social class, sexuality, ability, etc.).

Either by failing to make information about fieldwork publicly available or by failing to discuss sexual harassment explicitly, the (unintended) message from NAPs may be that talking about the realities of Antarctic fieldwork is not welcome or appropriate. In an era of #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter, acknowledging and reckoning with sexual harassment during fieldwork is a critical part of demonstrating a more fully developed understanding of the experience of fieldwork itself for many Antarctic expeditioners, especially those in underrepresented groups (e.g. women, people of colour, LGBTIQ+). It is imperative that expeditioners and NAPs themselves can critically reflect on how social identity relates to experiences of fieldwork, what this means for the polar workforce of the future and how NAPs can respond effectively.

One of the core issues that probably has confounded NAPs from grappling with sexual harassment consistently is the biased and exclusionary past of science itself and the challenges it poses for acknowledging lived experiences of different social groups (Metcalf et al. Reference Metcalf, Russell and Hill2018). As a result, various social groups have been systematically excluded and ignored because an acknowledgement of their experiences would call into question the objectivity and meritocracy of STEM.

Another confounding issue is that interpretations of sexual harassment can vary widely by national culture. Several countries with established NAPs do not have national laws that specifically prohibit workplace sexual harassment (e.g. Belarus, Korea, Russia). The absence of sexual harassment legislation provides little incentive for NAPs in these contexts to prevent it. For the three NAPs (Argentina, Australia, Germany) that did mention sexual harassment in their handbooks or field manuals, often it was done using gender-neutral language. This is an issue because the literature shows that sexual harassment is a function of patriarchy and women disproportionately suffer career consequences because of it (e.g. Leskinen et al. Reference Leskinen, Cortina and Kabat2011).

Although two NAPs explicitly referred to sexual harassment policies or ‘codes of conduct’ that expeditioners must adhere to, one consistent factor that emerged in this study is that few NAPs appear to be adequately preparing their expeditioners for what they may encounter in the field. Whilst it is possible that this information is covered in additional expeditioner training sessions, anecdotal evidence suggests otherwise. Antarctic expeditioners are largely left on their own to develop safety measures in the field and have relatively little training from their NAPs on sexual harassment during remote fieldwork. This is an important area for future research.

Recommendations

There is a growing body of research demonstrating the importance of organizational leadership in facilitating cultural change (e.g. Fusilier & Penrod Reference Fusilier and Penrod2015). In ASO research, this includes NAPs and international committees such as the Scientific Committee for Antarctic Research (SCAR) and the COMNAP. These bodies play a vital role in communicating the importance of building respectful field environments as well as setting expeditioner behaviour expectations and should be held accountable to new standards. It is incumbent upon NAPs and other relevant professional bodies to explicitly state that sexual harassment is not tolerated and to foster a culture of ‘upstanders’ - people who are ready to act and intervene when they witness harassment or other inappropriate behaviour in the field or elsewhere (Colaninno et al. Reference Colaninno, Lambert, Beahm and Drexler2020). These professional bodies can also use their influence to highlight and implement international best practices (e.g. NASEM 2018 recommendations) and to foster safe, supportive forums for people to discuss these issues openly.

Sexual harassment is associated with many significant negative health outcomes (see Leskinen et al. Reference Leskinen, Cortina and Kabat2011). Therefore, NAPs have a professional responsibility to treat sexual harassment as a serious work health and safety issue and provide much more expansive definitions of ‘risk’ and ‘danger’ in their expeditioner handbooks and/or field manuals so that expeditioners can assess their safety and make informed choices. The current narrow framing of risk has dangerous consequences for expeditioners.

The existing research reveals that employees feel better at work physically and psychologically when sexual harassment policies exist (e.g. Paludi & Paludi Reference Paludi, Paludi, Paludi and Paludi2003). In this light, developing and communicating effective harassment policies and procedures is critical to changing the culture of fieldwork because they demonstrate that an organization takes responsibility for harassment prevention in the first instance. It is, therefore, essential that NAPs explicitly define sexual harassment and set out individual and institutional responsibilities in their relevant documentation. Moreover, posting expeditioner handbooks and field manuals online and making sexual harassment policies publicly available make it possible to hold NAPs accountable. Doing so also makes the information available to job candidates/prospective expeditioners who may be interested in learning more about the NAP, or to existing expeditioners who need to source relevant information.

In line with best practice, it is crucial that expeditioners have information about multiple channels through which to make a complaint and understand how the reporting process works before they commence an expedition. Similarly, NAPs must supply expeditioners with details about the support available during the reporting and investigation process. This not only is essential for the expeditioner, but also reduces liability for the NAP and demonstrates that the NAP is operating ethically and is legally compliant.

The research demonstrates that women and those from other underrepresented groups are much less likely to report harassment due to power dynamics and perceived career ramifications (Cortina & Areguin Reference Cortina and Areguin2020). However, a well-communicated, accessible NAP sexual harassment policy can make it more likely that an expeditioner will make a complaint if they understand the policy and feel that a complaint will be taken seriously (McCann Reference McCann2005). Knowledge about a sexual harassment policy can also reduce fear in relation to reporting (Reese & Lindenberg Reference Reese and Lindenberg2003).

However, a key caveat is that it is not enough that sexual harassment policies and procedures merely exist - NAPs must regularly communicate the policies and appropriately train expeditioners in relation to their content (Reese & Lindenberg Reference Reese and Lindenberg2003). Training expeditioners is essential to solidifying the organizational commitment to harassment prevention. Cross-cultural differences in defining harassment could be addressed by educating expeditioners as appropriate.

Respectful, inclusive workplace environments do not happen by accident - they are intentionally created. One consistent factor that emerges across accounts of sexual harassment during Antarctic fieldwork is that many expeditioners feel that they were insufficiently prepared for what they would encounter (e.g. Nash et al. Reference Nash, Nielsen, Shaw, King, Lea and Bax2019). Expeditioners often discuss being on their own to develop safety measures and have had little training from their NAPs in these issues. Similarly, there is a strong need to normalize field safety measures in relation to sexual harassment across NAPs. Given that there are still many countries in the world where workplace sexual harassment is legal, it is incumbent upon NAPs in countries with strong laws to change how they interact with those that do not.

An effective and accessible sexual harassment policy is a foundational step in protecting expeditioners from harm and for improving Antarctic workplace cultures internationally. Moreover, it is essential that NAPs are more responsive to the needs of the diverse range of expeditioners working within the programmes. Although women are statistically the most common targets of sexual harassment, NAPs must be more attuned to intersectional oppression or the ways in which gender intersects with race, sexuality, ability and other features of social identity in harassment prevention efforts. Importantly, white, cisgender (heterosexual) Western perspectives need to be decentred if fieldwork is going to be properly inclusive and safe for all expeditioners.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful and constructive feedback. The author also acknowledges that she currently serves as Senior Advisor - Inclusion, Diversity, and Equity at the Australian Antarctic Division.

Author contributions

MN was solely responsible for the conceptualization, data acquisition, analysis, writing, reviewing and editing of the manuscript.