No CrossRef data available.

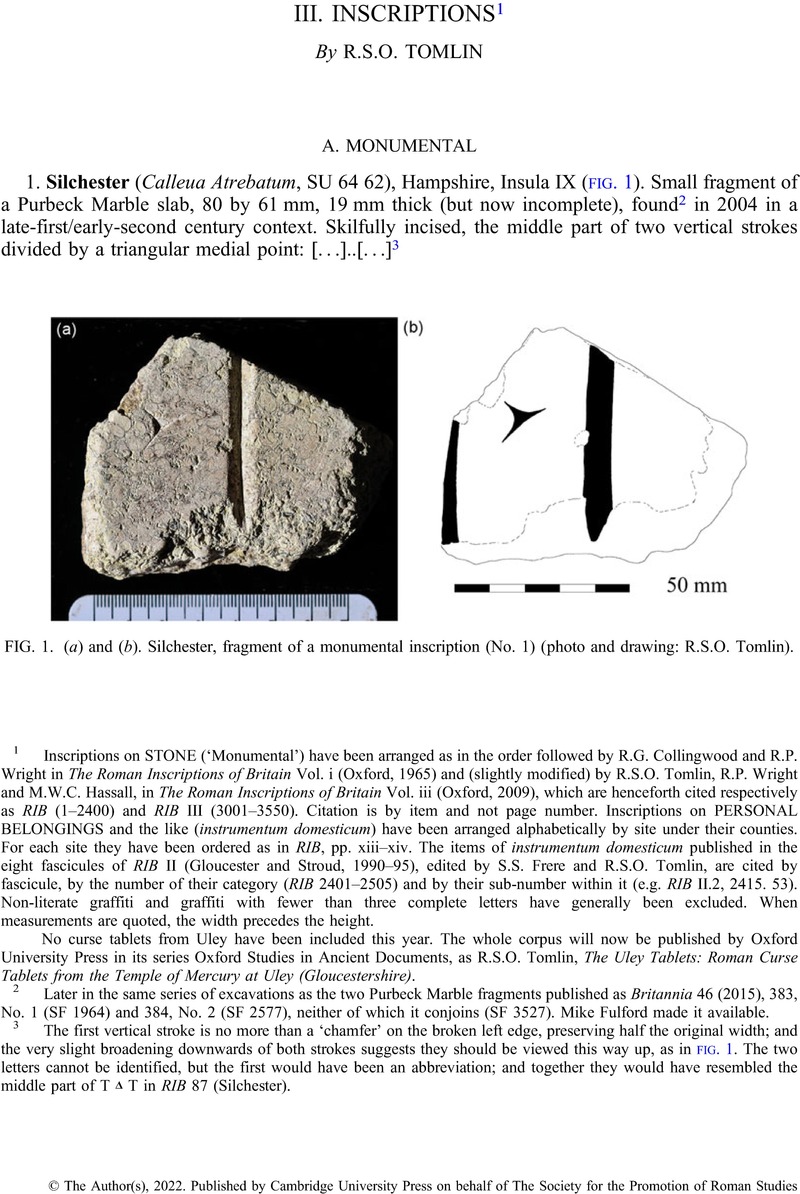

Article contents

III. INSCRIPTIONS

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 September 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Roman Britain in 2021

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Author(s), 2022. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of The Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies

Footnotes

Inscriptions on STONE (‘Monumental’) have been arranged as in the order followed by R.G. Collingwood and R.P. Wright in The Roman Inscriptions of Britain Vol. i (Oxford, 1965) and (slightly modified) by R.S.O. Tomlin, R.P. Wright and M.W.C. Hassall, in The Roman Inscriptions of Britain Vol. iii (Oxford, 2009), which are henceforth cited respectively as RIB (1–2400) and RIB III (3001–3550). Citation is by item and not page number. Inscriptions on PERSONAL BELONGINGS and the like (instrumentum domesticum) have been arranged alphabetically by site under their counties. For each site they have been ordered as in RIB, pp. xiii–xiv. The items of instrumentum domesticum published in the eight fascicules of RIB II (Gloucester and Stroud, 1990–95), edited by S.S. Frere and R.S.O. Tomlin, are cited by fascicule, by the number of their category (RIB 2401–2505) and by their sub-number within it (e.g. RIB II.2, 2415. 53). Non-literate graffiti and graffiti with fewer than three complete letters have generally been excluded. When measurements are quoted, the width precedes the height.

No curse tablets from Uley have been included this year. The whole corpus will now be published by Oxford University Press in its series Oxford Studies in Ancient Documents, as R.S.O. Tomlin, The Uley Tablets: Roman Curse Tablets from the Temple of Mercury at Uley (Gloucestershire).

References

2 Later in the same series of excavations as the two Purbeck Marble fragments published as Britannia 46 (2015), 383, No. 1 (SF 1964) and 384, No. 2 (SF 2577), neither of which it conjoins (SF 3527). Mike Fulford made it available.

3 The first vertical stroke is no more than a ‘chamfer’ on the broken left edge, preserving half the original width; and the very slight broadening downwards of both strokes suggests they should be viewed this way up, as in fig. 1. The two letters cannot be identified, but the first would have been an abbreviation; and together they would have resembled the middle part of T Δ T in RIB 87 (Silchester).

4 Quoting the caption below the drawing (fig. 2) ‘by Joseph Bonomi Esqr 26 September 1856’ in the commonplace book kept by the owner of Hartwell House, the astronomer and antiquarian John Lee (1783–1866), which is now MS Gunther 10 in the History of Science Museum, Oxford. Visitors contributed items on a wide variety of subjects including archaeology. Bonomi, whose gravestone identifies him as ‘sculptor traveller and archaeologist’, was an accomplished artist, an Egyptologist who in 1861 became the first curator of Sir John Soane's Museum. His drawing (at folio 217r) can therefore be trusted, but to say that the inscription was ‘found at Hartwell’ may be misleading. John Lee, who inherited Hartwell House in 1827, had travelled previously in Greece, Egypt and the Levant, where he acquired Greek inscriptions. He was a collector, and it seems more likely that he acquired this inscription too, rather than that it was first found at Hartwell. But a British provenance is quite possible; otherwise in Italy or some western, Latin-speaking province. Michael Metcalfe, who is making a study of Lee and his inscriptions, sent a photograph of Bonomi's drawing reproduced here by courtesy of the Museum. He notes that, although ‘black marble’ would suggest the provenance was not British, RIB 67 (Silchester) is also said to have been ‘black marble’. This too is now lost, but presumably it was cut like other Silchester inscriptions on Purbeck Marble, but (unlike No. 1 above) on one of its dark varieties.

5 The first line looks like alteri or alteri[us], meaning ‘the other’ (dative or genitive), but this does not indicate what sort of text it is. A possible restoration of lines 2 and 3 is modici[s sumptib]us, ‘at modest expense’, but MODICI[…] may represent the nomen Modicius, although it is rare. The sequence in line 5 does suggest a personal name, […u]s Fortu[natus], and perhaps the inscription is a list of personal names now reduced to their first or last letters: masculine in 2 (dative / ablative), 3 (nominative) and 5 (nominative), but feminine (accusative) in 4. […]O before MODICI[…] makes this difficult, since Modicius as a nomen would surely have been preceded by an abbreviated praenomen, but perhaps the O with its peculiar ‘stop’ in line 2 is a mis-reading of Q for Q(uintus).

6 By Paul Drury of the Drury McPherson Partnership, when it surveyed Caerwent House before restoration by the Spitalfields Preservation Trust. He sent details including a photograph, and Mark Lewis sent another from the Museum in Caerleon.

7 The diagonals conjoin and can be resolved variously as Ʌ, M, N or V. The sinuous line, if indeed it is a letter, would then be S. These marks are not certainly Roman, and even so, may only be ‘decorative’, but perhaps they extended right and left onto adjoining stones, to make two names; the first ending in –nus or –mus, the second beginning with N or M.

8 With the next item during excavation by the Vindolanda Trust directed by Andrew Birley, who made them available.

9 With possible trace of another letter to the right, and possible trace of letters above A and C, but they cannot be read and may well be casual wear-marks. Tacitus (in the genitive) is the mason's name, whether made on the quarry-face itself or when working the stone.

10 The cross-stroke has been extended to left and right, as if to form a ‘star’, which would suggest the letter stood alone as a mason's ‘signature’; the initial of his name, not part of a larger inscription.

11 With the next item and fragments of other silver or copper-alloy votives including RIB 215, 216 and 217, collectively known as the Stony Stratford Hoard although found in the nearby village of Passenham (Northants) a few hundred metres to the south-west. Now in the British Museum, where Ralph Jackson made them available. He catalogues the Hoard in chapter 6 of R. Jackson and G. Burleigh, Dea Senuna: Treasure, Cult and Ritual at Ashwell, Hertfordshire (2018), 74–109, where this item is SS10 at 87–8 with figs. 135–6, and (inscription) 119; the next item is SS72 at 96–7 with fig. 146, and (inscription) 120.

12 An abbreviated dedication, now incomplete, which cannot be resolved. A reference to c(ohors) II B[atavorum] seems unlikely.

13 During the same excavation by Wardell Armstrong Archaeology as the tombstone fragment published as Britannia 49 (2018), 429, No. 3. The director, Frank Giecco, made it available (WAA15 (541) <41>).

14 Lucius is not a praenomen but a nomen, as in Lucium Severinum (RIB 805, Moresby). The cognomen Curatus is also well attested; in Britain as the owner of a pewter vessel in Suffolk (RIB II.2, 2417.3, CVRATI).

15 In a curator's office at the Museum, when it was accessioned as COLEM 1999.31. Ben Paites sent a photograph and other details. The provenance is not recorded but is probably Colchester, like that of four other copper-alloy ansate plaques dedicated to deities, RIB 191 to Mars, 194 and 195 to Silvanus, RIB II.3, 2432.8 to Jupiter.

16 The text concluded with the formulaic V S L M, like RIB 194 (see previous note), which is also dot-punched. The name of the god is lost, and the dedicator's name incomplete. In the broken edge to the left of the first V are three dots, the tip of the preceding letter, which looks more like F than T, especially since Fuscus is a cognomen much more frequent than Tuscus. Between C and the second V is an elongated S, which may have been inserted afterwards. There is no final S, which must have been omitted or carried over to the second line.

17 By a metal-detectorist and acquired by Colchester Museum (COLEM 1999.30), from where Christine Jones made it available. It was presumably found in Colchester or nearby.

18 The date is deduced from the mixture of Old Roman Cursive letter-forms and New Roman Cursive: in fluminis (a.1), for example, the letters u, m and n are all NRC; but in fluminis (b.3), they are ORC. Yet fluminis in b.3 is immediately preceded by NRC m, and probably NRC u. Another NRC letter-form is e, made with two hooked strokes. ORC n is variously three straight strokes in fluminis (b.3) and inuolauit (b.5), but a downstroke cut by a curving upstroke in rahinas (b.3) and twice in a.5. ORC s is usually two strokes, but is apparently one long stroke before dona– (a.1) and as the first letter of a.5; in astalcias (a.2), if that is the reading, the first s is almost NRC. The letters p and r are difficult to distinguish, whereas in ceruical (a.4), r is almost ‘capital’. The scribe made downstrokes more firmly than horizontals, which in consequence have registered more faintly, if at all: thus in b.5, qui is now reduced to five downstrokes.

19 Transcribed letter by letter, underdotting those which are ambiguous or incomplete, and noting undeciphered letters with a stop (and three for an uncertain number). There is almost no word-separation, but it has been supplied where it can be deduced, for example after duas (a.3).

20 Line-by-line commentary

a.1, fluminis. This sequence is repeated in b.3, suggesting that (genitive) fluminis should be read in both places, but the verb donat (a.1–2) requires a subject which, at a guess, is a personal name beginning with s and o. But the next letters are ambiguous, perhaps b, s, u (now incomplete) and a long s, not amounting to a name which is attested. flumini (dative) would then be the indirect object, ‘to the river’, but no other curse tablet is known to be addressed to a river. But the river Rhine shares a dedication with Jupiter (CIL xiii 7791, compare 5255), and the genitive in b.3 may refer to an attribute of the river, as if it were divine (see below). Tablets addressed to Neptune are deposited in rivers.

a.2. The first letter apparently completes dona|t, but with o oddly close to it. Nothing can be made of what follows, except that it ends with –alium, which is surely a noun-ending, whether neuter, accusative or genitive plural. The next word is apparently astalcias, but the first s might be n, and the c another long s. It is feminine accusative plural since it is qualified by duas (‘two’) like rahinas (a.3), and like it is probably a garment, but nothing can be suggested.

a.3, rahinas duas. In view of what follows (‘coverlet’, ‘pillow’), this can be understood as a variant spelling of rachanas, a rare word (not in the Oxford Latin Dictionary) which Souter's Glossary of Later Latin glosses as ‘a garment’, ‘wrap’. It is well attested in Diocletian's Prices Edict, notably in 7.60, sagum sive rachanam rudem (‘cloak or wrap, unused’), where the adjective rudem is contrasted with ab usu (7.61) which means ‘used’. Two such ‘wraps’, rachanas duas, followed by tossiam Brit(annicam) (‘a British bedspread’), even feature in the list of clothing (etc.) sent by Claudius Paulinus, the governor of Lower Britain in a.d. 220, to a friend in Gaul (CIL xiii 3162, the ‘Thorigny Marble’).

a.3–4, copertorium ceruicale. copertorium (better spelt coopertorium, but it becomes coperta in Italian) is another rare word, meaning ‘a covering, garment’ (OLD). It is apparently followed by yet another noun, ceruical, ‘a pillow, cushion’ (OLD), unless this is the adjective ceruical[e], ‘for the neck’, descriptive of copertorium. Further to the right, the surface is broken by the fold and crumpled, resulting in the loss of several letters. The line clearly ends with –tecam, but nothing can be suggested.

a.5, sa..num rudem. Since rudem means ‘unused’ (see above), it must qualify a garment of some kind; and in view of the passage already quoted from Diocletian's Edict (7.60), perhaps the preceding word is a bungled sagum (‘cloak’). After rudem, the surface is crumpled again, and although the letters to the right are quite legible, nothing can be made of them. Perhaps they include the word pondo (‘by weight’), followed by a numeral.

b.1 is almost entirely lost; it may not even have extended the whole width.

b.2 clearly ends with –tralem (with m extended to mark the line-ending), but the preceding letter is difficult: perhaps s, which would suggest [de]stralem for dextralem (‘bracelet’). Compare Tab. Sulis 15, 2–3, destrale.

b.3, […]ium fluminis. As already noted, fluminis also occurs in a.1. Here in b.3 it is certainly genitive, so perhaps it was preceded by a word meaning an attribute ‘of the river’, for example its ‘genius’, [gen]ium fluminis, as if it were divine.

b.4. This line ends with –sius, and since the word is followed by the relative clause in b.5, its first two letters can be read as ip– (distorted, to avoid the long descender of the l from fluminis above) for ipsius, ‘of him’. The preceding word ends with –m, and might be a bungled animam, suggesting a curse upon ‘the life’ of the thief.

b.5, qui hoc inuolau[it]. There is space to the left of hoc, and the five strokes which begin the line can be read as the relative pronoun qui required by the formulaic hoc inuolau[it] (‘has stolen this’) by supposing that the horizontal strokes of q and u have been lost.

21 With the next item during excavation by Cotswold Archaeology. Details from Peter Warry.

22 RIB II.5, 2486.9.

23 RIB II.5, 2487.3.

24 With the next item during excavation by Cotswold Archaeology. Details from Peter Warry.

25 RIB II.5, 2488.2 with 2487.6, which are composite as Warry shows in Britannia 48 (2017), 108, fig. 8.

26 During excavation by Cotswold Archaeology (Britannia 49 (2018), 389). Details from Peter Warry, who notes that it was found c. 50 km from where it was made at Minety (Wilts), and probably arrived as hardcore since there is no evidence of tiled roofs where it was found.

27 RIB II.5, 2489.44F.

28 During excavation by the University of Reading (Britannia 50 (2019), 453–4) directed by Mike Fulford, who made it available. It was in the backfill of a trench from the 1903–04 excavation of the portico and latrine by the Society of Antiquaries.

29 Vergil, Aeneid iii 493 (trans. C. Day Lewis). This tag, from Aeneas’ farewell to Helenus, the founder of a new ‘little Troy’, was adapted by the authors of epitaphs to wish the survivors well, for example one from Brigetio (CIL iii 11306) which ends with just these words except for substituting beata (‘happy’) for peracta (‘accomplished’). It is also quoted by Sulpicius Severus at the end of the fourth century in a letter to Paulinus of Nola (Paulinus, ep. 22.3), but this seems to be its first occurrence as a graffito. A more familiar Vergilian tag, conticuere omnes, does occur at Silchester, on a box-flue tile (RIB II.5, 2491.148), but this is inscribed in fluent cursive letters much earlier in date: Mike Fulford notes that hexagonal stone roofing tiles do not replace ceramic at Silchester until the late-third or fourth century, and are then used for repairs to the bath-house. But, as Barrett shows (Britannia 9 (1978), 308), Vergil was still appreciated in fourth-century Britain.

The provenance of the graffito (see previous note) raises the question of whether it is a modern pastiche from the 1903–04 excavation, but this seems unlikely. As Fulford points out, the workforce consisted of farm labourers recruited locally, and only the two directors would have known some Vergil. The lettering, although informal, is acceptably Roman; its exaggerated serifs, the forms of A, F, N and V in particular, the lack of any word-separation (which has been supplied in the transcript above, for easier reading), the division between the lines of feli|ces and perac|ta, even the idiosyncratic centring of V and TA, none of this looks ‘modern’. The left margin of the text is original, and the way it observes the angle of the left-hand edge suggests that the tile was still hexagonal when it was inscribed; but since then, at least two pieces to the right have broken off and been lost, which would suggest that the graffito was already incomplete when it was unearthed, but not recognised, in the 1903–04 excavation.

30 In the same excavation as No. 1 above (SF 5716). Mike Fulford made it available.

31 The graffito is complete and should not be read inverted as VS; not only because such names are almost unknown, but because the junction of the two diagonals suits Ʌ, not V. It is the owner's name abbreviated to its first two letters: there are many possibilities, including Sabinus, Sanctus and Saturninus, and it is surprising that the scribe did not reduce them by adding a third letter.

32 During excavation by Chichester and District Archaeology Society. It will be published by Denise Allen, who sent a full description and photographs, one of which is a composite of the convex outer face. This has been reversed in fig. 12 to show how the lettering would have appeared from above.

33 ET (the conjunction ‘and’) would be part of an inscription running around the rim, whether exhortatory (‘use and enjoy’) or describing the whole scene. Below it is the ‘caption’ of a detail, but this is too fragmentary for restoration. Only the first letter, C, is complete. It is followed by I or L. The next line begins with B, P or R.

34 By a metal-detectorist. Information from Peter Reavill, finds liaison officer for Shropshire and Herefordshire, who sent photographs and commentary by Sally Worrell, John Pearce and Martin Henig. It is hoped that a local museum will acquire it.

35 AE is ligatured, and the first E of deae has been omitted. Since /e/ and /ae/ were pronounced the same, this is not unusual: RIB II.3, 2422.33, d(e)ae Senu(nae), is another instance on a (silver) ring. The Putley ring is rather small for an adult finger, but the wear to the lettering suggests it was actually worn, not just attached to a votive statue of Victory. It is the first ring dedicated to Victory to be found in Britain, but altars (etc.) are quite common.

36 With no further details. Information from Richard Hobbs, who sent the photograph from the TimeLine Auctions catalogue (No. 138, Lot 1035). Its present location is unknown, since an export ban has not been imposed.

37 The reading is restored from other instances of this maker's stamp (RIB II.2, 2415.5–7).

38 During excavation of the extra-mural Branch Road bath-house (Britannia 6 (1975), 258–60), in which the graffiti RIB II.8, 2503.235 and 277 were also found. It is now in Verulamium Museum (2006.733), from where David Thorold sent details including the photographs used to make fig. 15.

39 The reading is not in doubt, but E and R are incomplete; the fourth stroke of M is detached but linked to V, making it resemble N; V is cut by S, which is only a straight downstroke. Tenerrimus (‘most tender’) must be the owner's name, but is not otherwise attested. It is the superlative of tener which itself, although used in the epitaphs of persons ‘of tender years’ (teneris annis), is hardly found as a cognomen. The only instance seems to be the matronymic Tener[a]e in the Rothwell tablet noted below as Add. (f).

40 With the next ten items, as noted in Britannia 36 (2005), 489, No. 30, where the location is identified as ‘near Baldock’. They are now in the British Museum, where Ralph Jackson made them available, as part of the Ashwell Hoard which he catalogues in chapter 4 of R. Jackson and G. Burleigh, Dea Senuna: Treasure, Cult and Ritual at Ashwell, Hertfordshire (2018), 31–62. This figurine is A1 at 31–3 with figs. 49–51, and (inscription) 111; and is discussed with parallels at 126–30. The inscribed plaques, five of gold and five of silver, are cited similarly below in the note to each. The photographs and line-drawings in Dea Senuna have not been reproduced here, both to save space and because the British Museum, unlike other museums, charges the Roman Society for publishing its images. Also not included are four silver plaques (A19, A20, A26 and A27) which incorporate panels without any trace of lettering, either because they were never inscribed or were inscribed only in paint or ink.

41 For the goddess, her shrine and votaries, see Dea Senuna (previous note), especially 115–16 and 140–2. She was previously unknown, but her name, compounded from the Celtic element seno- (‘old’) and the suffix -una, occurs as a samian graffito (RIB II.7, 2501.505); and a silver ring from Kent (RIB II.3, 2422.33) can now be recognised as being dedicated to her, d(e)ae Senu(nae). The plaques, but not the figurine, give her the visual attributes of Minerva, without making the identification explicit. But like Sulis Minerva, the goddess of the hot spring at Bath, she may have been associated with the great spring at Ashwell, especially since the Ravenna Cosmography (108.40) lists a river in south Britain called Senua. The dedicator's name, Cunoris, is probably a variant of the masculine name Cunorix (RIB III, 3145), compounded from the elements cuno- (‘hound’) and rix (‘king’); names in –rix are sometimes feminine, for example Tancorix mulier at Old Carlisle (RIB 908).

42 A8 in Dea Senuna, 40–1 with figs. 66–7, and (inscription) 111. There are extra dots between D and E (the letters being a ‘Vulgar’ reduction of deae to de) and the medial point between B and M is made with two dots. It is rare for libens to be contracted to LB, and in Britain it is unusual for the dedicator's name to precede that of the deity, but A14 (No. 26 below) is another instance; the sequence is ambiguous in A12 (No. 25 below).

43 A9 in Dea Senuna, 41–2 with figs. 66–7, and (inscription) 112. This is the only plaque to omit the name of the goddess, whether for lack of space or because it was taken for granted. The basal tab was added separately and may have covered the final M of the formulaic V S L M, but A21 and A23 (Nos. 29 and 30 below) also conclude with V S L. The dedicator's nomen is unique, but must be cognate with the cognomen Cariatus (CIL xiii 4545), both of them incorporating the Celtic element kar- (‘love’). Her cognomen is also unique, but can be related to Ressatus and Ressilla which are well attested. However, the second ‘S’ might be T, which would result in Resta; but this is not otherwise attested.

44 A11 in Dea Senuna, 42–3 with figs. 70–1, and (inscription) 112. II is for E, as in A16 (No. 27 below). In the left field is what looks like a large S, but it can be resolved into a circular D with S crammed into it from below. In the middle of the bottom margin, M can be read from its three surviving diagonals, but only the tips survive of the letters to either side; however, they are consistent with LA and IIL for lamel(lam), for which compare the next item (with note). The dedicator's name, Nerus, is Celtic and probably cognate with that of the Nerusi, one of the Ligurian tribes listed on the Arch of Augustus (CIL v 7817 and Pliny, Nat. Hist. iii 136).

45 A12 in Dea Senuna, 43–4 with figs. 72–3, and (inscription) 113. Like the previous item, this calls itself a lamella (‘plaque’), but only one other plaque uses this term of itself: RIB 215 (Stony Stratford), as emended in Add. (a) below. The only other epigraphic instance of the word is in the Uley tablet (Britannia 29 (1998), 433, No. 1) which was prompted by the theft of lami[l]la una et anulli quat<tu>or (one ‘plaque’ and four ‘rings’ of gold or silver), but lamella is the term used by Marcellus Empiricus in De Medicamentis for amulets written on sheets of gold (lamella aurea, 8.59) or tin (lamella stagnea, 21.2 and 21.8).

46 A14 in Dea Senuna, 46–7 with figs. 76–7, and (inscription) 113. The dedicator's nomen is probably Bellius or Bellicius, both well attested in Gaul, and compounded from the Celtic element bel(l)- (‘strong’, ‘powerful’). As already noted for A8 (No. 22 above), his name precedes that of the deity, but this may be because space was limited; if his name had been written on the basal tab, it would have been obscured when the plaque was inserted into its stand.

47 A16 in Dea Senuna, 48–9 with figs. 80–1, and (inscription) 113–14. daeae for deae is hyper-correction of the ‘Vulgar’ confusion between /e/ /ae/ also seen in the Putley ring (No. 18 above). This is the only plaque to call the goddess Sena, whether it was an alternative but cognate form, or (more likely) by confusion with the dedicator's cognomen. This is Celtic, just as her nomen Lucilia, although Latin, probably ‘conceals’ the Celtic element luko- (?‘wolf’).

48 A17 in Dea Senuna, 49–50 with figs. 82–3, and (inscription) 114. The dedicator's nomen has been abbreviated to a single letter like his praenomen, which is unusual, but this was to save space and because the cognomen was distinctive, like T(itus) D(…) Cosconianus in RIB 1534. Herbonianus is unique, but must derive from the nomen Herbonius (usually written Erbonius) which is almost only found in Aquileia and north-eastern Italy (G. Alföldy, Die Personennamen in der römischen Provinz Dalmatia (1969), 83).

49 A21 in Dea Senuna, 54–5 with figs. 90–1, and (inscription) 114. The text was first lightly incised with a stylus as a guide to the dot-punched letters, SERVANDVS being written twice as the scribe tried to position it over the centre of the arch. This he achieved, but he was forced to abbreviate the name of the goddess and to extend HISPANI too far to the right for symmetry. The letter H is ‘lower-case’, formed as if cursive with its second vertical half the height of the first, a peculiarity shared by the next item (A23). Both plaques were struck from the same die, and carry the same legend. The dedicator was the same, and so probably was the craftsman who made and inscribed them, although their decoration is different.

50 A23 in Dea Senuna, 56–7 with figs. 94–5, and (inscription) 115. The text was first lightly incised with a stylus like the previous item, but SERVANDVS was only written once, suggesting that this plaque was the second to be inscribed.

51 A24 in Dea Senuna, 57–8 with figs. 96–7, and (inscription) 115. The scribe found it difficult to work retrograde: he had to correct the EN of Senun[ae] by cutting it twice. He made the third stroke of A with a single dot. By reconstructing the original width of the panel, it can be calculated that four letters have been lost at the end of each line: V S L M from the second; –AE from the first, followed by two letters for the rest of Firmanus’ name. His praenomen and nomen may have been reduced to single letters as in A17 (No. 28 above), but it is more likely that he bore an imperial nomen abbreviated to two letters like CL in A8 (No. 22 above) or FL for Fl(avius), for which compare A1 (No. 21 above).

52 Seen and photographed in the Guildhall Museum, Rochester, by Alan Montgomery, who informed Scott Vanderbilt. From the Museum Jeremy Clarke sent photographs, its records suggesting that the bowl was given to the Museum's first curator, George Payne (1848–1920). He was a leading Kent antiquary, and a local provenance is likely.

53 Two lines have been incised nearby, intersecting at right-angles: a ‘cross’ intended as a mark of identification, probably by another owner. This is the first British instance of the name Varinus which, like the more frequent Varianus, is developed from Varus although it may ‘conceal’ the Celtic element uaro-. That they both became part of the British name-stock is suggested by Varianus in a curse tablet from Uley (Britannia 20 (1989), 329, No. 3) and Varenus (with e) in the Kelvedon curse tablet (JRS 48 (1958), 150, No. 3).

54 During excavation by MoLA (Britannia 45 (2014), 370), in the fill of a ditch dated to the early/mid-second century (AHC07, context 2046). Charlotte Burn and Christine Fowler sent a photograph and other details.

55 E is capital-letter in form, but the ‘open’ R is cursive. M might be read as ɅX (for a name such as Hierax), but the letters would be rather close together; it looks more like a cramped M. Possible names include Germanus and one derived from Hermes such as Hermagoras, for which from London compare GER[…] (RIB II.7, 2501.211), HERM[…] (Britannia 37 (2006), 477, No. 26) and ?Hermatis (Britannia 40, 2009, 335, No. 32).

56 During excavation of a Romano-British building by Oxford Archaeology (East). Details from Ian Gilmour and Paddy Lambert, who sent photographs.

57 [F]ECIT (‘has made’) identifies the graffito as the brickmaker's signature. This verb would have been preceded by his name and, quite likely, by the date and/or the number of bricks in the batch. The line above ends with the apparent sequence ENII, and the space to the left, between E and the vertical stroke just inside the broken edge, suggests that this letter was T. The resulting […]TENII cannot be part of a numeral or date, but must be part of the name. At first sight it ends in a genitive, but the subject of [F]ECIT would have been nominative, so it looks as if the brickmaker wrote ]TENTI, cramming T and I together as space ran out, and finishing T with a perfunctory cross-stroke like IT in [F]ECIT just below. He would then have begun the next line with NVS for Potentinus, quite a common name and the only one that seems to fit; but since this [NVS] would have brought the left margin further to the left than [PO] in the line above, there must have been some further space, in one or both lines. This would have been filled by a numeral, for the number of bricks made, and perhaps also by the date; but it is more likely that the graffito was headed by the date in a third line above, now lost entirely.

58 With Britannia 47 (2016), 404–6, Nos. 19–21, during excavation by the Upper Nene Archaeological Society directed by Roy Friendship-Taylor, who made it available. It will go to the site museum.

59 A few lines are less deeply incised and have been drawn in outline. This caricature cannot be paralleled in Romano-British curse tablets, but the three short straight lines converging at lower right are evidently an ‘arrow-head’. The caricature must have depicted the victim of the curse and the fate intended for him, but this cannot be confirmed from the text overleaf.

60 The right edge is original and preserves the ends of the first three lines. The fourth line is very incomplete, and only three letters remain of the fifth. The inner face is less corroded than the outer, and most of the letters preserved in its right-hand portion are still quite legible, but apart from de suo in line 1 and uir in line 3, they cannot be readily resolved into Latin words. Since it is written on lead, it is surely a curse tablet, as indeed the outer face suggests (see previous note), but the text does not seem to be Latin, not even Latin reversed or enciphered. Perhaps it is Celtic transcribed.

61 Published with full commentary by G.D. Tully as ‘A fragment of a military diploma for Pannonia found in northern England’, Britannia 36 (2005), 375–82. First recorded with this provenance in a private collection in Bath, it is now owned by the University of Queensland. Since the recipient served in Pannonia, the transmitted provenance is too vague to be certain: the fragment might have been found in Hungary, for example, and brought to England in the antiquities trade. The recipient and his unit are unknown, but Tully shows that he might have been a Briton recruited into the ala I Flavia Augusta Britannica when, as its title suggests, it was raised in Britain; after serving in Pannonia, he might then have returned as a veteran to his native province. For another such instance, compare now the Lanchester diploma (Britannia 48 (2017), 460, No. 17 with 49 (2018), 458, Add. (f)), which was issued to a veteran of the German Fleet but found in northern England.

62 With the next two items in the same excavation as the lead sealing published as Britannia 26 (1995), 382, No. 15. Alex Croom, who is writing up the excavation, made them available. They are SF 158.1, 22.4 and 85.4 respectively.

63 The graffito is complete, but its reading and interpretation remain uncertain until another instance is found. The central letter might be read as either c or t, but the name *Samca is not attested and the ‘medial point’ would be difficult to explain; so perhaps the stylus rested here before making the cross-stroke of t. Samta is only once attested, as the maker's mark on an ‘Apulian’ amphora found in north-east Spain (Hispania Epigraphica 15 (2009), 42, No. 81). The second part of the graffito is also difficult. HS might be read, but II s(emis) seems more likely, the numerals being separated by medial points: ‘two and one-half’ would then suggest that the potter was being credited with making two amphoras and ‘one-half’ of another. Millet 2019 (cited below in n. 100), 126, shows that a Dressel 20 was made in two parts, but does not cite any graffito referring to only ‘one-half’ of one.

64 The sequence of strokes and the placing of the graffito require it to be read this way up, and not as ɅX. Numerals are quite often scratched underneath samian vessels (RIB II.7, 2501.837–70), perhaps to identify them within a ‘set’; for another instance of ‘15’, see RIB II.7, 2501.862.

65 Apparently part of an ownership-inscription, the owner (his name now lost) identifying himself by his unit. Since the ala II Asturum was the garrison of Chesters from c. a.d. 180, its restoration here is inevitable, whether Asturum was abbreviated or not. But the numeral is difficult since it is on a slightly lower alignment, and consists of the upper portion of two vertical strokes, the first crossed by a long diagonal. Unless this is casual scoring, it would seem to be a misplaced suprascript line marking II as a numeral (‘2’).

66 Like the next three items and Add. (h) and (i) below, presumably in an early excavation. All were inscribed after firing. They are now stored with other amphora sherds from Housesteads (but these with only one or two letters each) at Corbridge Roman Site, from where Frances McIntosh made them available.

67 The graffito is broken by the top edge, so is not necessarily complete, but the surface to its left and right is not inscribed. The first ‘letter’ is incomplete, a long downward diagonal to the left which does not suit any letter of capital form, especially in view of the sequence FORT which follows; but it would suit a centurial sign made by linking two diagonal strokes. After FORT is what looks like V, but with a faint upward continuation of the second diagonal. In view of the uninscribed space to the right, this might be read as I linked to S without lifting the stylus, but since the cognomen Fortunatus is much more frequent than Fortis, and V is the easier reading, it is probable that the name was never completed. The owner, whose name is now lost above, identified himself by the century to which he belonged, and abbreviated the name of his centurion. There are two British references to a centurion called Fortunatus, RIB 1907 (Birdoswald, in the Sixth Legion) and Tab. Vindol. 351 (unspecified).

68 There is just enough space to the left of G to suggest it is the first letter, and a nick in the edge to the left of Ʌ would suit G, although it might only be casual damage. (C would then also be possible.) But G is a more attractive reading than C in view of the unique but well attested name Gauuo or Gauo at Vindolanda (Tab. Vindol. II, 192, 207 and 218). Like Tagadunius (Add. (h) below), also from Housesteads, it might well be a Tungrian personal name. But if the reading were CAV[…], then compare Caus (RIB II.8, 2503.222) and even Caurus, if the dedicator of RIB 1079 were CAVR…

69 Part of a name, presumably, but with no obvious candidate. utere felix, ‘Use (this and be) happy’, is very frequent on objects of domestic use, but seems unlikely in this context, where an owner's name would be expected.

70 With the next nine items during excavation by the Vindolanda Trust directed by Andrew Birley, who made them available. The two sherds of this item are SF 22964 and SF 22965, but the amphora has not yet been identified; it does not look like Dressel 20.

71 The long diagonal line below the other letters is the tail of s, now incomplete, exaggerated to mark it as the final letter. The name Victor (in the genitive case) is the potter's ‘signature’, whether it was written by himself or by a supervisor who was literate. The same ‘signature’ was found at Wallsend (see Add. (d) below).

72 SF 22587. The third letter might be M, but it would be rather wide; Ʌ is the better reading. Ianuarius (in the nominative or genitive case) is the only common name suggested by the sequence –nua– , and at Vindolanda it is found in Tab. Vindol. 861 as the name of a centurion.

73 SF 22469. The mould-maker's signature, apparently that of Iustus ii of Lezoux, who often ligatured the letters T and I in this way. But there is no exact match of the whole composition in the instances of his signature collected by the RGZM website <www1.rgzm.de/samian/home/frames.htm>.

74 SF 22463. This cognomen also occurs at Corbridge (RIB 1180) and is that of a centurion at Vindolanda (Tab. Vindol. 892).

75 SF 22516. The letters are incomplete, and only the extreme tail of R survives; but it should not be read as part of Ʌ or N, since the sequence ]AIN[ or ]NM[ would be most unlikely, whereas the name Primus (etc.) is very common. The case was nominative or genitive. At Vindolanda it has already occurred twice as an ownership-graffito, in RIB II.7, 2501.448 (PRIM[…]) and Britannia 40 (2009), 349, No. 72 (PRIMI[…]), as well as in Tab. Vindol. 180.28, Primo Luci; 181.6, ab Primo; ?793, a Prim[o]; 347, Primigenio; App. 418, Primigenius; 606, [Pri]migenio.

76 SF 22850, in the nominative or genitive case. Only the end of a diagonal stroke survives of the letter after V, but its angle suits N, not R. Moreover, Secundus and its derivatives are much more common than Securus, and M should not be read, since there are no names in Secum–. Apart from the prefect Pituanius Secundus (RIB 1685), the cognomen Secundus occurs at Vindolanda in Tab Vindol. 861 (a list of names) and perhaps in the unpublished tablet WT 2017.34, besides being that of the author of Tab Vindol. 869, a letter received at Vindolanda. In 2022 a stone was found there naming Secundinus, which will be published next year.

77 SF 22692. The sequence VIR is clear, with the tail of R prolonged and cut by the following letters. The first of these is apparently I, and VIRI would suggest the common name Virilis, already attested at Vindolanda by Tab. Vindol. 310, but to the left of V is an angular figure formed by three lines. This might be an exaggerated Ʌ, or not even a letter at all, but a mark of identification formed by two lines meeting at an angle crossed by a third. To the right of VIRI is a confusing sequence of three letters which might be read as (first) C or a curving L; (then) a vertical stroke (‘I’) leading to (third) a horizontal stroke cut by a diagonal at its further end. This third letter might be read as S set at right-angles to the preceding letter because of the limited space available. Virilis is thus quite a possible reading, preceded by a figure which might be a centurial sign followed by the initial letter I, say for I(uli) or I(anuari), the centurion's name abbreviated; but this cannot be certain.

78 SF 22605. The first surviving letter might be T with the cross-bar missing, as suggested by the space between the incomplete first vertical stroke and C, but the sequence–tcicio would be very unlikely. However, […]ICICIO does not suggest a name either. Perhaps the scribe intended SIINIICIO for Senecio, but inadvertently repeated CI. Senecio is a common cognomen, and has occurred at Vindolanda in Tab. Vindol. 609.9, where the editors note Sene[…] in 188.2 and ?Senicio in App. 206 margin 1 as other possibilities.

79 SF 22901. V is not quite complete, and L is made with a short initial up-stroke. […]MO[…] should not be read, since the final stroke of ‘M’ would be too vertical, and the ‘O’ clumsily formed. But too little remains to be sure of [Ci]vil[is], although it is quite a common name.

80 SF 22645. The letters are crowded together, and R is exaggerated in size. Only part of a diagonal stroke remains of the final letter, but the angle suits V rather than I, for the nominative in –us. The cognomen Severinus is quite common, and at Vindolanda occurs in Tab. Vindol. 215.3 and 640 (a letter written to Severinus).

81 By a metal-detectorist. Information from Sally Worrell, who sent a photograph. It is not yet available on the PAS database, but its unique ID is NMS-CF7FEE; its Treasure Case tracking number, 2021T330.

82 For other silver rings dedicated to Mercury see RIB II.3, 2422.20 (Corbridge), DEO MER; 29 (Vindolanda), MER; 30 (Billingford), MER; Britannia 25 (1994), 306, No. 39 (Great Walsingham / Wighton), MER; 27 (1996), 451–3, No. 29 (Stowmarket), DEO MER.

83 With the next item in systematic metal-detecting before the temple was excavated in 2014. Richard Henry made them available (SF 41240 and SF 90366 respectively), and they are now in Salisbury Museum. See R. Henry, D. Roberts and S. Roskams, ‘A Roman temple from southern Britain: religious practice in landscape contexts’, Antiquaries Journal 101 (2021), 79–105, in which both tablets are briefly described at 90–92 with line-drawings and translation. A third inscribed tablet (SF 41431) was also found, but it remains descriptum. It is an irregular fragment, 55 by 33 mm, of a lead strip which was folded twice. Its inner face retains traces of six lines of Old Roman Cursive, now shallow and much damaged, in which a few letters such as s and t can be recognised, but no words.

84 Line-by-line commentary

Face (a)

1, Bregneo. The preceding deo (‘god’), and the word's position in the first line, marks it as the name of a god in the dative case; the reference to ‘your’ temple (9) confirms that a god is being addressed. But the name Bregneus (nominative) is otherwise unknown, and does not relate easily to any Celtic name or title. However, compare the masculine form of ‘Brigantia’ (the eponymous goddess of the northern tribe of the Brigantes), deo Breganti on an altar from Yorkshire (RIB 623). This raises the possibility of confusion between /e/ and /i/, suggesting that Bregneus incorporates the element brigo- (‘high’) found in Brigantes and other place-names, or the element brigo- (‘valiant’) in personal names such as Brigomaglos and Briginus. But this does not warrant identifying Bregneus with Bregans, a specifically north-British god.

2, securim. Three other British curse tablets seem to have been prompted by a stolen axe: Britannia 22 (1991), 293, No. 1 (no provenance), securam(!); 30 (1999), 378, No. 3 (‘Marlborough Downs’), secur[im]; 35 (2004), 336, No. 3 (Ratcliffe-on-Soar), duas ocrias ascia(m) scalpru(m) ma(n)ica(m) (‘two gaiters, an axe, a knife, a pair of gloves’). The last is of particular interest, since it itemises protective clothing associated with an axe and knife, which would have been appropriate to woodland management or land clearance. Five miniature iron axes were found at the ‘South Wiltshire’ temple (Antiquaries Journal 101 (2021), 94).

3, de hospitio meo. This phrase (‘from my house’) occurs in five other British curse tablets: Tab. Sulis 99, de hos<i>pitio suo; Britannia 15 (1984), 336, No. 7 (corrected in Britannia 22 (1991), 309 corr. (d)) (Pagans Hill), de hospitiolo m[eo]; Britannia 24 (1993), 310, No. 2 (Ratcliffe-on-Soar), de (h)ospitio; Britannia 10 (1979), 344, No. 4 with Britannia 22 (1991), 307, corr. (a) (Uley), de hos[pitio or -pitiolo]; Britannia 23 (1992), 310, No. 5 (Uley), de hospitiolo meo. This sixth instance, from yet another rural location, strengthens the conclusion that hospitium, although it means ‘lodging’ in Classical Latin, in the ‘Vulgar’, spoken Latin of Roman Britain meant ‘house’ or ‘home’.

4, Hegemonis. The reading looks good except for the first letter, but here the slight traces are still compatible with H. This is a Greek personal name (meaning ‘leader’) which is sometimes found in the West, but is previously unattested in Britain; it is surprising to find it in a rural location, where ‘Celtic’ or ‘Roman’ names would be usual.

This possessive genitive sits awkwardly with meo, but the sense is ‘from my house, (the house) of Hegemon’, Hegemon being the author's name. It would more easily have followed deo Bregneo in the nominative, but there is another instance of this awkward syntax in Britannia 51 (2020), 487, No. 13 (Uley), in which the unnamed writer curses whoever has stolen a sheep ‘from the property of Virilis’, [de pro]prio Virilis.

5, ..NAEVM inuolauit. The accusative ending –um before the verb inuolauit (‘has stolen’) would suggest the object of theft, but this has already been specified as an ‘axe’ (securim). But if the word is eum (‘him’, ‘it’), it can hardly refer to this axe, since securim is feminine (and thus followed by quam in 2), so that eam would be appropriate. But a similar confusion of genders may occur in 11–12. The context of inuolauit requires a formulaic clause introduced by ut qui or si quis (‘whoever has stolen the axe …’), but this cannot be read in the traces to the left of eum.

6–7, non [i]lli somnus nec | sa[n]itas permittatu[r]. The interdiction of health until the thief returns the stolen property is formulaic in British curse tablets (for other instances see Tab. Sulis, pp. 65–6, s.v. non permittas), but the passive permittatur is unusual; it is also found in a tablet from Uley (Britannia 48 (2017), 462, No. 10).

The conjunction donec (‘until’) or nisi (‘unless’) has been omitted before pertulerit: for this formulation, see Tab. Sulis, pp. 63 and 65. donec would be more logical, and perhaps the scribe's eye was caught by NEC just above, but nisi would be much more usual. There is no sign that he wrote it below sa[n]itas, where the rounded edge is original, so he must have omitted it by oversight as he turned the tablet over from face (a) to face (b).

Face (b)

8–9, pertulerit usq[ue] | ad tem(p)lum tuu[m]. There is no sign of nisi to the left of line 8 (see previous note). The formula of returning stolen goods ‘to the temple’ is frequent at Bath and Uley (see Tab. Sulis, p. 68, s.v. templum). usque ad often reinforces the preposition ad in Latin, but this is the first instance in a British curse tablet; it also occurs in the other ‘South Wiltshire’ tablet (next item). The Lydney tablet (RIB 306) uses the phrase usque templum [No]dentis.

ad tem(p)lum tuu[m]. The scribe seems to have ligatured E to T, by adding a medial horizontal stroke to T, but he omitted P altogether. There is an isolated P at the end of the next line, after the verb-ending –ponimus, as if it were added as an afterthought.

10, ut componimus. Reading and meaning are difficult. M is half lost, PO is ‘underlined’ with an exaggerated bottom serif, and there is almost no trace of the first stroke of N (which is lightly made elsewhere). For no apparent reason the writer is shifting from first-person singular perdidi (4) to first-person plural componimus, before returning to singular perdidi in 12. The verb is indicative, meaning that ut is being used parenthetically in the sense of ‘as’. It would seem that this ‘arranging’ (componimus) refers to the condition that the axe is to be returned to the temple, but imponimus (‘imposing’ a condition) might have been better.

11, martulum. martulus (in the nominative) is a variant spelling, as dictionaries note, of the word marculus meaning a ‘hammer’ or ‘mallet’. As a tool it would be close to an axe; miniature hammers were also found at the temple (Antiq. J. 101 (2021), 92).

11–12, quam | prius. The apparent inversion of priusquam (‘before’) would be most unusual, and it seems more likely that quam is a relative pronoun (feminine) dependent on martulum (‘the hammer which I have lost’), despite the confusion of genders. It should have been quem (masculine), but perhaps this was a mistake like eum in 5. prius might then be taken without quam as a temporal adverb (‘previously’).

12, eum. tum (‘then’) might almost be read, but the first letter has a detached medial stroke for E with an exaggerated top-serif, like that in pertulerit (8). The masculine eum (‘him’, ‘it’) surely refers to martulum despite the confusion of genders introduced by the feminine quam just noted.

13, MV[.]NIT. This can hardly be munit or mu[n]ivit, since this verb is used of ‘fortifying’ or ‘road-making’, but perhaps the scribe wrote MVENIT, intending inuenit (‘has found’) or even inueniat (‘let him find’). This verb is often used of the god's ‘discovery’ of a thief, for example in the other ‘South Wiltshire’ tablet (next item), and it might have been used here to refer to the god's ‘finding’ the lost hammer. But the syntax is difficult to reconstruct.

14–15. Illegible traces, followed by what looks like do (‘I give’), which would be repeated from line 1. The ‘previously lost hammer’ (martulum quam prius perdidi) would then be its object.

85 With three different forms of e: conventionally a downstroke leading into an upstroke (as in usque), a downstroke with short medial stroke (as in perferat), and even a double ‘hook’ (as in the second eum of 3, but not unlike that in inueniat). The only p (in perferat) is indistinguishable from t.

86 Line-by-line commentary

1, cana.larem. The accusative ending in –arem marks this as the object of inuolo|uit (‘has stolen’), and thus the object of theft. But although it clearly ends in –arem, the preceding letters have been obscured by a build-up of corrosion products: they are most likely cana, then faint trace of a letter linked to the downstroke of l, its diagonal almost lost in corrosion. There is no obvious candidate, but an attractive one is capitularem (‘cap’), the object stolen in Tab. Sulis 55 and the London Guildhall Yard tablet (Britannia 34 (2003), 362, No. 2), with variant spellings in the Caistor St Edmund tablet (13 (1982), 362, No. 9) (cap(t)olare) and an unpublished Uley tablet (No. 62, capitlarem). But the third letter (most likely n, but possible e or s) cannot be read as p.

1–2, inuolo|uit. The last letter of line 1 is undoubtedly o, not a, and this deviant spelling of inuolauit is apparently repeated later in 2. With the tonic vowel assimilated to the pre-tonic vowel, it may reflect local pronunciation; but in 4 the verb, although damaged, is clearly written with an a. The other ‘South Wiltshire’ tablet (previous item) writes inuolauit correctly. inuolouit may be only a writer's slip, therefore, but another deviant spelling, inualauit with the reverse assimilation, is often found: at Uley (Britannia 27 (1998), 439, No. 1; 48 (2017), 461, No. 10; and two unpublished fragments), Pagans Hill (Britannia 15 (1984), 339, No. 7), Silchester (Britannia 40 (2009), 323, No. 16).

2, si dexter. The conditional si would suggest that dexter (‘on the right hand’) is the first half of a pair of mutually exclusive alternatives ‘defining’ the thief. These are frequent, notably si seruus si liber (‘whether slave or free’), but the pairing ‘whether right or left’ is not otherwise known. Dexter is quite a common cognomen, but the thief would hardly have been named, especially since the god is to ‘find’ him. That it was the writer's name is not supported by the syntax.

inueniat (‘let him find’) is formulaic in the sense of the god (deus) ‘finding’ the thief: compare Tab. Sulis 99, 4–5, deus illum inueniat; and 44, 12–14, qui rem ipsam inuolaui[t] deus [i]nuenia[t], where further examples are noted. But although inueniat is followed by the object illum (‘him’), the next word, deum, is not nominative and explicitly the subject; but the context requires this, and the scribe must have carelessly repeated the accusative case-ending of illum … eum … illum.

3, qui eum qui illum. Relative pronoun and demonstrative are repeated, by oversight presumably, like the error just noted of deum.

4, inuo[l]a[ui]t. The verb is much damaged, and l has been lost entirely, but five letters (inu, a and t) are well preserved, and the other traces allow the restoration of inuolauit. This is the correct spelling, unlike inuolouit in 1 and 2 (see above).

perfera(t). As already noted, the first letter resembles the preceding t, but is acceptable as p, since both letters were made in much the same way, with a hooked stroke crossed by a second stroke which was horizontal or a downward diagonal. The resulting sequence per- supports this reading. In this context, perfera[t] is an easy restoration, since like inuolare and inuenire, this verb is formulaic, in the sense of ‘bringing’ the stolen goods to the god's temple: compare pertulerit in the other ‘South Wiltshire’ tablet (previous item); and Tab. Sulis 10, 17–19, ad templum sui numinis per(t)ulerit, where further examples are noted.

4–5, ad usque | t[emplum tuum] is an easy restoration, despite templum being reduced to its initial letter and trace of two more, since this phrase occurs in the other tablet. Corrosion makes it impossible to be sure that the possessive pronoun tuum was added, or replaced by eius (‘his’).

87 With the next item during a watching-brief by Simon Reames Archaeology. Details from Peter Warry.

88 RIB II.4, 2459.36.

89 The first instance of this stamp, with the mark left by a nail or peg mid-way like RIB II.4, 2459, 43–45. Peter Warry notes that the impression is c. 4 mm deeper here than at either end, indicating that the die had flexed. This weakness, suggesting that the die did not long survive, may explain why it has not been found before.

90 With the next item during excavation by Cotswold Archaeology. Details from Peter Warry, who notes that the bottom left corner of this stamp should be drawn as if square, not indented as in RIB.

91 RIB II.4, 2459.19.

92 RIB II.4, 2459.41. Peter Warry notes that the die was not impressed vertically, but was rolled across the rounded surface. It is thus rather faint, and appears to be shorter than it was. The only other instance is from Seaton, Devonshire.

93 In ploughsoil above Barrack 2 during excavation for the Scottish Development Department directed by W.S. Hanson (Britannia 18 (1987), 313 and 19 (1988), 429). It is fully published by Lindsay Allason-Jones in W.S. Hanson, Elginhaugh: A Flavian Fort and its Annexe (2007), Vol. II, 411, No. 59 with fig. 10.31.

94 By the same maker as RIB II.2, 2412.1 (Wereham), where this second instance is noted but not published as being ‘after the closure-date for RIB ii’. However, as Scott Vanderbilt has noticed, it did not then achieve the annual report of ‘Inscriptions’ in Britannia.

95 Now in the British Museum, where Ralph Jackson made them available. They were drawn by Richard Smirke (1778–1815) for S. Lysons, Reliquiae Britannico-Romanae (1801–17), II.ii, pl. xxxix 7 (not ‘10’, as in RIB), 10 and 9 respectively. His engraving is reproduced as fig. 123 in R. Jackson and G. Burleigh, Dea Senuna: Treasure, Cult and Ritual at Ashwell, Hertfordshire (2018), 80, which publishes the three plaques with photographs and new drawings by Craig Williams: RIB 215 as SS6a at 83–4 with 118 (inscription); RIB 216 as SS51 at 95 with 119 (inscription); RIB 217 as SS75 at 97 with 120 (inscription). The Stony Stratford Hoard includes two other inscribed fragments, not in RIB, which are now Nos. 6 and 7 above.

96 RIB reads lines 9–10 as PRO VO|TO SOLVTO P D, pro uo|to soluto p(ecuniam) d(edi), but SOLVTO cannot be read from Smirke's drawing or the traces which remain. The first letter is more like L than S, and the second letter is certainly A (which was read by Huebner in CIL vii 80). The rest of the line is badly worn, but there is a diagonal stroke in the right place for the fourth stroke of M, prompting the restoration of lam[ell]a, now that two plaques in the Ashwell Hoard (Nos. 24 and 25 above) confirm that this word was used in the sense of ‘(votive) plaque’. There is trace of two letters at the end of the line, the first a diagonal stroke appropriate to the A of lamella, the second a vertical stroke followed by a curving stroke, more like P than D or R.

97 Now in the British Museum, where Ralph Jackson made them available. They have been drawn by Craig Williams for R. Jackson and G. Burleigh, Dea Senuna: Treasure, Cult and Ritual at Ashwell, Hertfordshire (2018), 116–17, where they are B4, B3 and B8 respectively.

98 Dea Senuna, 116. DVM is not separated from the previous word ALATORI by a medial point, suggesting they should be taken together, like the words of the dedicator's name, CENSORINVS and GEMELLI.

99 Dea Senuna, 117. The new drawing shows the lettering in better detail, but represents C as G; but the apparent ‘tail’ (which RIB ignores) is only casual damage. RIB reads nu(mini) V(o)lcano, since this is the usual spelling of the god's name, but numini is hardly ever abbreviated to NV, whereas N is frequent. n(umini) Vulc(an)o is thus more likely, for which spelling compare RIB 899 with VLK for V(u)lk(ano) .

100 As shown by Berni Millet in publishing another instance of this potter's ‘signature’ from the Brijuni villa: see his ‘Calendar graffiti on Dressel 20 amphorae’, chapter 10 in T. Bezeczky (ed.), Amphora Research in Castrum Villa on Brijuni Island (2019), especially 134–38. As well as correcting RIB II.6, 2493.6 and 46 and Britannia 46 (2015), 410, No. 50 (Add. (g) below), Millet adds further instances from Altenstadt, Saint-Thibéry, Reims and Béziers.

101 Compare the second instance of this ‘signature’ now found at Vindolanda (No. 44 above).

102 As Scott Vanderbilt has noted.

103 Steven Willis, The Roman Roadside Settlement and Multi-Period Ritual Complex at Nettleton and Rothwell, Lincolnshire (2013), 284–8, with figs. 6.58 (two line-drawings), 6.59 (two photographs), 6.60 (detail of handwriting). It is expected that it will be displayed at the Arts and Heritage Centre, Caistor (Lincs).

104 The characteristic s of Asiaticus’ ‘signature’, a simple downstroke trending left (see the drawing and photograph of RIB II.6, 2493.6), was mis-read as the first stroke of II for e.

105 Like the next item, in store at Corbridge Roman Site, from where Frances McIntosh made them available.

106 This personal name, apparently Tungrian, was suggested after reading the left-hand sherd from a photograph as ɅGɅD.[… ] (Britannia 52 (2021), 479, n. 44). To the left of the first Ʌ, two faint lines intersect at right angles and, if they are not casual, may indicate where T should have been added. The new sherd supports this reading, with a gap for a missing letter followed by the incomplete strokes of two letters appropriate to I and V.

107 The new sherd confirms the initial Ʌ, and shows that the cognomen Atticus was not preceded by a nomen, which means that the name which follows in the genitive case must be a (peregrine) patronymic. (That the writer wrote OPTI to identify himself as an opti(o) seems unlikely.) His father's name was Optus, or at least ended in –optus, in the genitive case. The name Optus is difficult to parallel, but OPTI, presumably genitive, occurs as the name of a glass-maker in CIL iii 6014, 6 (Bregenz). Otherwise it might be an error for Op(ta)ti, ‘(son) of Optatus’.

108 Information from Lindsay Allason-Jones and the owner. The altar was already badly worn when drawn by R.P. Wright in 1945, but fig. 38 confirms the accuracy of his drawing. There is good trace of L (or E) in the middle of the top line, which may mean that it began with COH (with O ligatured to H, as in RIB 1859, etc.) followed by a widely spaced II (‘2’) and then LIN, for coh(ortis) II Lin(gonum), referring to the commanding officer and his family. This cohort is attested at Moresby (RIB 798 and 800), the next fort along the coast, six miles to the north. Moresby at 3.5 acres is ‘rather tight for a mixed infantry and cavalry cohort’ (D.J. Breeze, Handbook to the Roman Wall (2006), 412), and Burrow Walls is even smaller (3 acres); so perhaps the cohort was divided between the two forts. In combined area they would have been equivalent to Lanchester (6.17 acres), the fort garrisoned by its sister-unit, cohors I Lingonum.

109 Where it was seen (object G–1878-1029-1) by Scott Vanderbilt.

110 It is described with the text correctly transcribed by F.E. Cottrell-Dormer in his Account of Rousham, Oxfordshire (1865), 31–2, who says it was ‘brought from Rome in the last century’.

111 This tombstone is still in the Palazzo Rinuccini, and there is a photograph of it in Wikimedia Commons. The stonecutter correctly heightened the second I of DIIS and the I of CLAVDI, to mark them as ‘long’, but some of his letters have since been restored incorrectly with black paint. The text became ILS 1643.

112 In his apparatus he cites authority for the two (incorrect) readings he accepted, as well as authority for the two variants he rejected, which in fact were correct. The correct reading of the right-hand panel is Serviliae | Aproni | pientissime, which may be translated: ‘(and) to Servilia Ap(h)ro, most devotedly’. Obviously it was left blank when she devoted the left-hand panel to her late husband, Claudius Daus, and was only inscribed after her own death.

113 AE 1977, 509 = J.J. Wilkes, ‘Roman Inscriptions in the City of Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery’, PBSR 44 (1976), 28–43, at 32 (No. 6) with Pl. Va. It was the only one of these inscriptions not to be recorded in CIL vi and elsewhere, but the limestone is of Mediterranean, perhaps (north?) Italian, origin, so Wilkes concludes that it was brought to Britain by a collector in the eighteenth or nineteenth century.

114 Information from the stonecutter, Nicholas Tower, now a retired doctor, who left the project unfinished when he went to medical school. He cut IMPNI | COLA on the slab, intending it to be part of an altar dedicated by IMP NI|COLA[S].