Abstract

Background

The quality-of-care assessment is an important indicator of the efficiency of a healthcare system. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), despite the implementation of the holistic care model for the treatment of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) victims, little is known about the client’s perception of this model and its outcome. This study aimed to examine the expected and perceived satisfaction of service recipients through the One-Stop-Center model of health care in eastern DRC.

Methodology

This descriptive and analytical cross-sectional study was conducted at Panzi Hospital (PH), in eastern DRC. Data were collected by a mixed-methods approach, 64 Victims of Sexual Violence participated in individual (in-depth) interviews and 150 completed the Survey. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare the mean item scores of sexual violence victims’ satisfaction.

Results

The findings from our qualitative analysis demonstrated that the victims admitted at PH had various expectations and needs on arrival depending on their social identity and residence locations. For instance, the VSVs coming from remote areas with ongoing armed conflicts mentioned concerns related to their security in the post-treatment period and the risks of re-victimization that this could incur. Conversely, those who came from the urban neighborhood, with relative security raised various concerns related to their legal reparation and ongoing access to other support services. With scores above 4, victims of sexual violence were extremely satisfied with the overall care provided and wished that PH could continue to support them mentally and financially for an effective reintegration into their communities. The Kruskal–Wallis analysis confirmed statistically significant differences (p < 0.1) in satisfaction with legal support based on the victims' residential locations, social support based on their age groups, occupational therapy based on their religious denominations, and accommodation based on their professional activity.

Conclusions

Results of this study suggest that victims’ satisfaction with support services is based on either the organizational frameworks of clinical or support services within the hospital and the victims’ social environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Backgrounds

Quality-of-care assessment is a core element of health system performance and a growing area of interest in contemporary human services and clinical settings [1, 2]. In High-Income Countries like Australia, Canada, the United States, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, quality of care is systematically reported as part of overall health system performance reports [3]. The reported health outcomes often stem from different indicators, one of them is the patient-reported indicators [4]. Patient-reported experience measure (PREM) and patient-reported outcomes measure (PROM) are quantitative instruments for measuring, respectively, the patient's perception of the care and the patients' self-reported overview of their health status [5, 6]. Several measures and tools (composite health care satisfaction index, discharge questionnaire, integrated customer observatory, indicator of the overall quality of patient care, service quality scale, dashboard, and audit) have been used to measure patient satisfaction. These multiple measures allow each problem to be addressed in its context and serve as effective tools for managing decision-making throughout the health system governance chain [7,8,9]. Typically, these indicators address different dimensions of service recipients’ experience, including communication with practitioners, physical and emotional support, and access to information, care received, and others. In addition, satisfaction is measured using self-assessment questionnaires that analyse elements and factors of good care, including contextual, relational, and medical skills factors [10, 11].

In Low-Income Countries (LIC) like the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), quality-of-care assessment and patient-reported indicators in particular are subject to multiple complexities related to the lack of standardized tools of measurement, limited involvement of service recipients in health care decisions and limited health infrastructures. As an example, to date, the DRC has no permanent information system on the quality and safety of care. Recent studies assessing the quality of care through satisfaction analysis were accessed in three mid-level hospitals of Kinshasa (the capital of DRC) and used the modified Service Quality Scale [12, 13]. Wolomby‐Molondo et al. [14] studied the relationship between insecurity and the quality of care provided for abortion complications in 24 DRC facilities. This study examined 12 infrastructure and capability readiness criteria using the WHO Multi-country Survey on Abortion Complications. The authors discovered disparities in the quality of care related to infrastructure, supply, and human resources in secure and insecure areas. Clarke-Deelder et al. [15] discovered that, despite the fact that the Integrated Management of Childhood Illnesses (IMCI) strategy was implemented for about two decades, adherence to IMCI protocols for the severe disease remains remarkably low in the country. The assessment of hospital performance on quality of care in South Kivu province, eastern DRC, is based on the DRC Ministry of Health's standards for the management of the general referral hospital [16]. Different measures used in these studies only allowed evaluating the quality of care of all patients encountered in health care structures. Indeed, quality-of-care assessment enables healthcare institutions to improve the quality of services and managing healthcare professionals’ behaviors. It promotes cost-effectiveness, limited iatrogenic risks, and patients’ satisfaction in terms of procedures, outcomes, and human contact within the health care system [17].

Sexual and Gender-Based Violence (SGBV) is one of the most critical areas of healthcare services delivery where quality-of-care assessment is of high relevance. While different interventions are in place to respond to the multidimensional needs of SGBV victims [18], there are limited studies focused on the quality-of-care assessment and victims’ experiences with health services providers [19]. Essentially, SGBV is a particularly sensitive health problem and victims may have subjective feelings about the quality of care and high expectations towards access to care and safety guarantees [9]. Other parameters, such as the physical characteristics and resources of the health service, are related to care satisfaction. Because responses to technical standards alone are no longer sufficient, satisfactory responses to perceived quality of care are also needed from service recipients [8, 9, 20].

Humanitarian and health professionals are refining methodologies to expand and improve services to victims and increase the capacity of local organisations to address the impact of sexual violence on individuals' and communities' personal, physical, social, and mental health [18, 21]. The WHO international guidelines [22, 23] have been developed to provide comprehensive guidance to victims in order for them to receive forensic, medical, and psychological care during the emergency phase, as well as adequate medical, psychological, and social follow-up care for a period of time following the violence [24]. Significant efforts are being made to provide an effective and ethical response while respecting and empathising with the victims [21]. OSC models of care have been developed globally, and in low-income countries in particular, as a means of extending quality services during post-conflict reconstruction and recovery [25].

In the three past decades, a holistic model based on innovative and patient-centred model of care has been developed at PH for victims of sexual violence [25]. Putting victims at the centre of care involves respecting their preferences and values, promoting provider-patient interaction, and managing the quality-of-care system effectively (i.e., accessible, equitable, effective, safe, and efficient). This model aims to place the victim at the centre of their care by prioritizing their rights, needs, and wishes [9, 26,27,28]. This study's focus was guided by the following questions: (1) What are the expectations of victims of sexual violence in the PH OSC model?; (2) What is the satisfaction level of the victims on the quality of care offered by the PH?, and (3) In the OSC model, what are the victims' unmet needs? This study, conducted at the PH, aimed at assessing the gap between the expected and perceived satisfactions of victims of sexual violence. Thus, a better understanding of the reasons for victims’ satisfaction should help managers and policymakers to develop programs that meet the needs of beneficiaries. The research approach adopted in this study includes all information related to victims' judgments about aspects of care, particularly the interpersonal dimension, as victims are now the primary care partners in the holistic model at PH. In this approach, care recipients were not asked to rate their health or discharge status after treatment [8, 29, 30] but were rather asked for their level of satisfaction post-care. Finally, involving victims in quality assessment is a means of empowering them and developing support services that are tailored to their specific contexts.

2 Brief overview of PH and Holistic model of Care

PH is known as the centre of excellence in the holistic management of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) in eastern DRC [31]. One-Stop Centre (OSC) was developed after years of treating girls and women who had been raped and suffered severe bodily harm. Victims of sexual violence received only medical care from 1999 to 2003. Psychological care was added to medical care in 2004. Legal and socioeconomic assistance were added to the OSC model in 2008. Patients come from all over the city of Bukavu in the South Kivu province, and elsewhere in DRC. During their stay, they receive holistic care in the OSC [25, 32] by benefiting from a complete package through four pillars: medical, psychological, legal, and socio-economic reintegration. The Panzi OSC model provides more than just holistic individual care; it also serves as a platform for achieving healthy living at the micro, meso, and macro levels, thereby facilitating the realisation of the right to health for all [25]. On arrival, they are eager to recover from their physical, psychological, and from economic conditions, and regain their human dignity. From their admission, they are treated and accompanied by a multidisciplinary team of medical, psychosocial, legal, and socio-economic specialists. Figure 1 briefly illustrates the OSC model of caring for victims.

The care begins in the patients' homes thanks to referral partners. These partners are local and international humanitarian non-governmental organizations, associations, health facilities, churches, but also the judicial police and/or judicial authorities for medical expertise. The mission of the community partner organizations is to identify sexual and gender-based violence cases in their communities and screen them according to the criteria of the Panzi OSC model of care. They elaborate the transfer forms and ensure the continuity of the referrals until the VSVs are admitted to PH.

Upon admission to Panzi, the patient is welcomed to the reception desk for preliminary listening, registration, and orientation to the care process. Clients are invited to sign the consent form as soon as they are admitted. They are then allocated a psychosocial assistant (PSA or "Maman Cherie") who provides regular and permanent support and follow-up for their clients during the entire care period. Patients are first screened, and those with tuberculosis, malnutrition, or psychosis, HIV, syphilis or vaginal infections are identified. Those who require surgical treatment as a result of rape or childbirth trauma are treated [31]. On arrival at the hospital, the victims were first subjected to medical (within 24 h of admission) and psychological (within 72 h of admission) care. Medical care includes the full healthcare package of each patient in order to address the patient's individual needs. Medical care is offered by doctors and nurses according to specific protocols that are in accordance with national and international norms. Doctors explain the medical procedure and a consent form is signed before any medical treatment is carried out. Victims identified within 72 h of the incident receive specific and emergency medical care for preventing pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections thanks to the post-exposure prophylaxis kit (PEP Kit). Patients from outside the city of Bukavu are hosted in adapted accommodation houses where they received food. PSAs conduct counselling and psycho-education on hygiene and on care procedures. The intervention of the PSA is reinforced by clinical psychologists who, furthermore, provide psychological consultations and apply the appropriate therapies for psychological pathology diagnosed. Several psycho-social activities are conducted for the victims, including ergotherapy, musical therapy, recreational excursions, family mediation, and aftercare services at home, home-based escorting of victims who have been rejected by their families or abandoned by their spouses due to sexual violence, and community reintegration. During their stay at PH, patients received on-going training in literacy and vocational trainings (making flowers, gloves, baskets, embroidery, and sewing). This psychosocial assistance (ergotherapy), which aims to heal through learning, allows them not to be bored, and to interact with other victims during training sessions. This activity also aims to equip these women with certain business skills that could be useful in their socio-economic reintegration process. Legal assistance is firstly provided through awareness sessions on Human Rights and activities organized by the legal pillar. Victims who consent to legal assistance are guided by the legal department, which is made up of lawyers who ensure the progress of the complaint until the perpetrator is detained and sentenced. Doctors deliver a medico-legal certificate and a medical report to clarify the incident's severity to the courts. When a patient is declared safe by a multidisciplinary committee meeting which involves both pillars, the Panzi OSC model transmits a counter-referral report to the partner organization that referred the patient in order to maintain post-care follow-up. To improve the quality of this specific care [12, 33, 34], PH through the victms of sexual violence holistic care service organizes a weekly assessment of the quality of care through a survey to measure satisfaction with care among patients before their discharge.

3 Methodology

3.1 Design

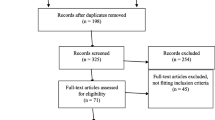

This is a descriptive and analytical cross-sectional study conducted for a year (from April 2020 to March 2021) at PH. Data were collected through a mixed-methods approach combining quantitative (self-administered satisfaction survey) and qualitative (in-depth interviews of patients' expectations).

3.2 Sampling procedures and data collection

The study method was divided into two parts and was used depending on the time between admission and participation [24]. In-depth interviews were conducted from the 5th day after admission, and the survey took place before victims were released [35]. Victims over the age of 15 were eligible to participate because this is the legal age of consent in the DRC [36]. During the research period, 1143 victims were admitted to PH, with 4% being men and 39% being children. Random sampling was used to collect quantitative data. Panzi Hospital organises a weekly clearance programme for victims who have been discharged. Each week, 3 to 5 victims were chosen from a list of discharged victims to participate in the survey. The in-depth interviews were organised by convenience sampling. A total of 150 victims have been surveyed at the time of their respective discharge from the hospital and 64 were interviewed. Refusal rates were 40 victims (21% of potential respondents) due to time constraints or some, who were most likely deeply traumatised by the rape, were unwilling to respond to questions. If the eligible respondent was not available, two attempts were made to contact and reschedule an interview.

Interview guides were used to collect data on victims' expectations during their brief stay at Panzi. Respondents were generally asked to describe their feelings when they were informed that they would be treated at PH, as well as aspects of their lives that they would like to see changed. The data collection instruments included Likert scale questions (1 = very dissatisfied to 5 = very satisfied) allowing an evaluation of the quality of healthcare. The questionnaire used was sourced from the international standard model for the care of SGBV inspired by the European Union's Humanitarian Commission [37,38,39]. Although Congolese legislators have already elaborated the texts, no official documentation is available for the quality assessment of care provided by the various stakeholders to victims of sexual violence in the country. The survey questions helped us to identify the socio-demographic profiles and assess the level of satisfaction of the respondents from the time of admission to the day of the data collection. Thus, variables relating to reception, orientation (accommodation, catering, and hygiene), treatment in the different pillars (medical, psychosocial, legal and social support), and the preparation for leaving were collected (Table 1). The survey questionnaire included open-ended questions in which respondents provided clarification on aspects not covered by the PH OSC model.

Clear explanations were provided to the respondents about the study objectives before the discussions. The respondent as well as the investigator had to sign the informed consent before starting the survey and the discussion (interview). Two informed consents were signed by the minor, and their parent or his/her legal representative [40]. In strict compliance with the ethical values of confidentiality and anonymity of the respondent, the form was set up in Kobo Collect and, therefore, the data collection was done with tablets. All questions were administered by the first and third authors of this paper in Swahili or in a local language of the respondents. The interviews and survey were conducted in an office of a care organisation at PH. The victim's age and a pseudonym were assigned in accordance with the interviews' participants. This nickname was proposed individually by each victim and referred to the name that the victim likes apart from his/her own name.

3.3 Data analysis

We used Thematic Framework Analysis to connect the structure of the research questions to the data collected, allowing us to interpret the field data in greater detail and nuance [24]. Examples of quotes from participants were used to argue and illustrate the themes extracted from the data in detail. The calculation of frequencies of the mean scores per item and its relative percentage was performed by the ratio between the number of respondents for each score and the total number of respondents for that item.

The percentage score for each item was obtained by dividing the average score by 5 and multiplying the ratio by 100 [8]. Descriptive statistics were used to generate a demographic profile of respondents as well as to examine the frequency (%) of respondents receiving care in various services in the OSC model. Mean, median, standard deviation, and interval were used to describe items [35]. Because the data collected through our Likert scale questionnaire was ordinal, parametric ANOVA was not appropriate in this case. In contrast, the Kruskal–Wallis test proved to be an appropriate methodological solution for comparing more than two independent groups [41, 42]. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to assess the relationship between patient experiences and overall satisfaction with the OSC model of care [43]. The Kruskal–Wallis test is a non-parametric test that is equivalent to a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test [41]. The P < 0.1 was considered statistically significant. Microsoft Excel and Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) were used to encode, arrange, and analyse the data.

Although the data collected and analysed in this study assessed the quality of care provided by the OSC model, the data presented was not free of self-reporting bias. Firstly, while during the first referral interview, PSAs provide victims with preliminary explanations about the care package offered by PH. Some participants' responses were based more on their desire to be quickly healed and recovered from the consequences of the rape without being aware of the ideal plan. To minimise bias, we re-explained the PH care package, allowing victims to define their expectations. Second, the OSC model's assessment of care quality was influenced by the services in which the victims were treated. Some victims had a pessimistic or optimistic assessment depending on whether the care package was used to treat other complaints unrelated to the rape incident. Other victims' satisfaction was defined by their fear of the future, particularly those from high-risk areas. An ongoing feedback meeting with OSC model practitioners aided in focusing on effective improvements in care and support strategies.

4 Results

4.1 Sociodemographic characteristics of victims

The average age of respondents was 30.26. Table 2 shows that the victims coming from Bukavu city are mostly minors (67% of them are below 15–17); those coming from rural South-Kivu are young to middle age adult women (74% of them were 18–44). 78% of victims from outside South Kivu province are over the age of 25. Regarding religion, about 48% of victims were Catholics; 42% were Protestants; 2% were Muslims, and 8% were others religions. In terms of education, 32% had officially started school but had not completed elementary (primary) school, 21% had not completed high school, only 8% had a high school certificate and 6% had started university. They were mostly farmers for adults (74%), students (22%) for minors and the others were engaged in other activities (trade, handicraft). There were statistically significant differences in the age distribution, education and activity of victims, comparing those from Bukavu City, to those from outside the city, and to those from outside the province. This was explained by the fact that in Bukavu City, the rape of minors is increasingly recurrent and is perpetrated by civilian men (in most cases, a relative to the victim). In rural South-Kivu areas (Kabare, Walungu, Kalehe, Fizi, Uvira, and Mwenga territories), sexual violence is mainly by armed forces and is more likely to be perpetrated against young adult women. Illiteracy was higher (above 32%) in rural South Kivu and outside the province than in urban areas (11%). Agricultural activity employs more than 80% of the victims from rural areas, compared to 22% in Bukavu city. Some of these women had already given birth (> 20%) after sexual violence and others (~ 16%) had pregnancies from Rape. These victims are constantly troubled by the uncertainty of the life of their children born from rape. It is a great obstacle to their moral, social, religious and even decision-making development.

4.2 Expectations of victims of sexual violence on arrival at PH

The findings from our qualitative inquiry demonstrated that the victims admitted at PH had various expectations and needs on arrival depending on their social identity and residence locations. For instance, the victims coming from remote areas with on-going armed conflicts mentioned concerns related to their security in the post-treatment period and the risks of re-victimization that this could incur. Conversely, those who came from urban neighbourhood, with relative security raised various concerns related to their legal reparation and on-going access to other support services. Victims admitted at PH expected for physical and psychological restoration, and they needed socio-economic reintegration and legal support. Some victims indicated that they hoped to regain their dignity, and that their psychological and physical pain will be healed. Therefore, they were expecting to leave PH stronger than they were at on the day of their arrival. Before reaching PH, new patients typically received testimonies and sensitization from previous patients as well as local stakeholders. They hoped that the time at PH would enable them to live again with people who take care of them, encourage them, motivate them, and help them to resume their lives on the right basis.

Box 1

“I came to Panzi because I could not stand it any longer. I had been totally destroyed by the perpetrators. I was no longer a person. I did not need anything anymore (...), my whole body was destroyed; I couldn't sleep anymore because the psychological pain was enormous. These people ruined my whole life, (...). I knew that father Mukwege (Medical Director of PH) and his team would first treat me and then take care of the rest of my life [Kabwe (pseudonym), 38-year-old]’’.

These victims declared that they were also looted as perpetrators have taken away everything that they possessed (money, clothes, destroyed houses, killed husbands and other family members, etc.). Faced with this context, they also hoped for a socio-economic reintegration in which they would be accompanied in their communities and would receive subsidies to allow them start afresh with their economic activities. Apart from those coming from Bukavu or those who have already complained to the courts, women from rural areas thought less about legal procedures. They were able to reposition this in their expectations after the sensitization and support sessions with Panzi staff. Ultimately, victims admitted to Panzi hoped that the holistic care they received from Panzi should be accessible, safe, and participative. They testified that they knew better their problems, had a greater understanding of the environments from which they came, and needed to recover their dignity quickly.

4.3 Victims of Sexual Violence’s satisfactions with the holistic car model

The result from the quantitative analysis (Table 3) demonstrated the overall satisfaction of the client from the support services. We found more than 80% (average score greater than 4) of victims treated at PH are satisfied with the variety of care provided in each pillar. The level of victim satisfaction was determined by both the individual respondent and the services provided by the OSC model. Catering, social support, and Ergotherapy had slightly lower scores (a score of 1 indicates complete dissatisfaction), and were more evenly distributed (with an SD > 0.6).

Table 4 compared the ranking mean of the Kruskal–Wallis test on the satisfaction items of the victims' origin, age, religion, and activity.

The results presented in Table 4 showed that the average satisfaction scores of the various items under study varied depending on the victim's origin, age, religion, and activity. For certain items, there were statistically significant differences (at the 10% level). There was a statistically significant difference in legal support based on the victims' ranked means of origin. Victims from Bukavu reported an average level of satisfaction of 51%, followed by those from outside South Kivu at 50.68% and those from rural South Kivu at 39.5%. The legal follow-up is conducted by the legal clinic team, which is in charge of raising awareness of human rights, particularly women's rights, and following up on the patients' legal cases. Victims of various ages perceived social support differently. Victims aged 45 and over were 93% satisfied, while victims aged 25–34 were 64% satisfied. Victims aged 25–44 reported that the rape had severely harmed their social lives, to the point where they had lost trust and confidence in their surroundings. They desired for total rehabilitation through the treatment they received at Panzi and hoped that PH could continue to support them mentally and financially for an effective reintegration into their communities. The socio-economic reintegration of patients begins at the PH by raising awareness and evaluating the needs for the reintegration of each woman. The role of the PSA is to involve the patient in the entire process of her care.

Box 2

‘’ (...) everywhere I have been, it is only at PH where I have found that every patient has a Maman Cherie (PSA). They look after us and support us during this difficult time. It is true that the doctors treated me, but it is through the guidance of my maman cherie, I am who I am today [Yvette (pseudonym), a 25-year-old]’’.

80% of Protestant women were satisfied with the occupational therapy activities, while less than 40% of Muslim women were. PH is a Protestant facility that bases certain activities on Christian values without discriminating against other religions' values and activities. As a result, women of other religions would be expected to adhere to the values upheld by the care provider to some extent. Women engaged in activities other than farming and studying rated their satisfaction with the quality of accommodation during their hospital stay at 41%. Victims are housed in communal rooms at PH. These women stated that, independent of the room conditions, sleeping in a common room did not allow them to enjoy their privacy and was the source of some misunderstandings.

We found no statistically significant differences in medical and psychological care because the victims were unable to objectively assess the quality of their medical and psychological care. Their physical and psychological state at the time of the survey was used to determine their level of satisfaction. They reported that they had psychological and physical pain before and, following treatment, which had disappeared. Furthermore, dissatisfaction with medical care was common in failed fistula repairs (2%). Counseling was organised for these critical patients to assist them in their ongoing recovery process, which may take longer than expected.

4.4 Unmet needs within the holistic care model

The accessibility of care depends on the distance between PH and certain parts of the province of South-Kivu, and even the country. Patients from neighbouring provinces have reported that it is difficult for them to get to Panzi in order to receive quality holistic care.

Box 4

‘’ (...) from our place in Kalemie, we know that Father Dr. Mukwege is the defender and repairer of abused women. I did not hesitate to think about coming to Panzi to receive treatment. At home, there is no road to reach here and it takes a long time to be here even by boat. Only on arrival, I knew that I could be protected from sexually transmitted diseases if I were on time [Sephora (pseudonym), 28-year-old].’’

Victims of sexual violence had reported that the care received at PH did not guarantee their complete security. Victims living outside Bukavu city acknowledged that Panzi is far unable to reassure them of the security in their communities. The perpetrators live in the community and still exert a certain threat to the victims.

Box 3

‘’ (...) I am proud of my current status. PH has just given a new sense to my life. The whole time I was here I could not really complain. However, I am grateful to the Panzi officials and the nursing staff. One thing I fear is that I will be going home soon. I am still in danger of ending up with that ferocious man who abused me with all his gang of criminals. I know that Panzi has done everything for me but I realize that it is unable to continue providing my security when I will be back home. This is what still bothers me (...); [Antoinnette (pseudonym, 30-year-old woman]’’.

Despite all the efforts made by PH, the care of victims of sexual violence is faced with several challenges. There are still challenges to the effective implementation of a standard protocol for the care of victims that promises dignity and respect for the woman; non-discrimination in care and information, and respect for confidentiality. In order to get out of the chaotic situation in which they find themselves, victims say that the care at the PH must also include rehabilitation and support for family members and/or the community.

5 Discussion

The findings from our qualitative analysis demonstrated that the victims admitted at PH had various expectations and needs on arrival depending on their social identity and residence locations. Although victims admitted to PH had varying expectations and needs, they all expected physical and psychological restoration as well as socioeconomic reintegration and legal assistance. The Chi-square test for demographic variables revealed a statistically significant (p < 0.01) relationship between the victims' origin and their age, education, and occupation. The Kruskal–Wallis analysis confirmed statistically significant differences (p < 0.1) in satisfaction with legal support based on the victims' different areas of origin, social support based on their age groups, occupational therapy based on their religious denominations, and accommodation based on their professional activity categories. The Victims of Sexual Violence care at PH is a response to a humanitarian concern. Understanding the beneficiaries' perception of the quality of care allows the providers to refocus their actions [27, 44, 45]. From this study, ~ 80% (~ score 4) of the victims’ expectations were met at PH. They acknowledge that the quality of care met their expectations because the humiliations endured as a result of the rapes were resolved at PH. Previous studies have shown that patients have a high satisfaction rate after they are discharged [10, 12, 13, 17, 46, 47].

Several factors promote patients’ satisfaction, including sociodemographic and expectation factors [13]. Results showed that victims from settings highly affected by war and sexual violence reported satisfaction with the free, quality care of which they were the beneficiaries. Most rural women are vulnerable and depend solely on agriculture for their livelihood. After the incident of rape, they were unable to take the initiative to go to the hospital because they were abandoned by their family members and would not be able to cover the costs of care by themselves. In DRC, access to quality health care is a challenge for public health because the use of primary care is about 0.3 visits per person per year; an average below the World Health Organization (WHO) standard [48]. Some people die at home or engage in uncontrolled traditional treatment due to a lack of means to seek treatment at health centres.

The victims indicated that the very fact that they were able to unburden themselves and denounce all the crimes of which they were victims and file a complaint against alleged perpetrators completely relieved them because, in rural areas, it is almost difficult to speak out after the abuse for fear of being prosecuted by their torturers. The persistence of impunity in the DRC, which allows perpetrators to go free regardless of their actions, makes them even more aggressive towards women who dare to denounce them [49, 50]. We found that reporting rape in urban settings is more likely by minors than in rural settings [51]. This non-reporting of sexual violations is in line with the population's norms and beliefs that it is difficult for an adult woman to report sexual abuse because ipso facto she will be subject to ridicule and social discrimination [50, 52]. Also, according to Perrin et al. [53], the authoritarian position of the African man makes any married woman who is sexually abused, unable to report it for fear of being repudiated by her husband. Adolescent girls and young adults have demonstrated enormous social support needs. According to Wemmers et al. [54], victims of sexual violence blame themselves for their victimisation and the reactions of their surroundings. Sexual victimisation has had a wide range of personal and interpersonal consequences, including a loss of self-esteem and trust in men and others in general. These and other victims are suffering from post-traumatic symptoms (nightmares, intrusive thoughts of trauma or flashbacks, hypervigilant behaviour, anxiety or depression, certain sexual disturbances, and eating disorders) [55, 56].

Being at the centre of their care and fully involved in the process of their recovery, victims reported that this contributed to their restoration within a reasonable time frame [57]. The integrated model of care of victim of sexual violence aims to restore their dignity and well-being. Each team is facilitated by trained providers who follow care standard established by the World Health Organization [25, 58]. In its implementation, the OSC model has a management circuit that must be respected by the different teams. In the meetings that bring together the multidisciplinary teams (doctors, psychologists, PSA, and lawyers), an integrated support plan for the patient is established and the victim’s follow-up is facilitated by ''PSA or Maman Cherie'' and psychologists. At this point, it is a question of tracing the entire course of the victims to be prepared for the return to the community as well.

Although the OSC model is currently showing significant progress among providers at PH, it still has limitations because it does not integrate the actions of other primary and secondary health care providers. This is because the other actors have never fully adopted the achievements of this model. An effort still needs to be made between the pioneer of the OSC model on the one hand and the stakeholders (the health division, health facilities, non-governmental organizations and local associations) in the management of victims in the province of South-Kivu in particular and those of DRC in general. In addition to this, the international and national system for combating gender-based violence has only put in place a few guidelines for better medical management of victims but has never established a standard management protocol involving the four pillars [38, 59]. In their intervention, each stakeholder then sets the prerogatives to accompany the victims [39, 60]. PH should therefore propose the advances of the OSC model to other authorities, taking into account its experience and expertise in the holistic management of victims.

6 Limitations of the study

This study did not address all aspects of this broad analysis. Although we collected perception data from victims during their stay at PH. It was difficult to track them all back to their communities because some had decided to change their physical environment after receiving care at PH. The continuous improvement of the OSC model was also the basis for various modifications of the quality-of-care assessment tools. In addition, our analysis focused on medical and psychosocial care, as these are the two pillars that are fully provided at PH. For the other two pillars (legal and socioeconomic reintegration), although the support process begins in the hospital, it often ends when patients are no longer in the hospital. We did not collect responses from victims under the age of 15 or their parents because the data collection protocol was limited to victims who were of legal age to provide informed consent and could participate in the self-interview or survey without the assistance of an intermediary.

Our findings should be taken with caution, because patients could have limited knowledge on the medical support patterns/techniques and advanced psychiatric/psychosocial aspects of trauma healing. This might justify why they were more satisfied by the home visiting and social support and rarely mentioned the medical pillar, yet one of the most important aspect of treatment. We recommend that future studies evaluate the different tools and protocols used by all stakeholders in the management of victims as well as evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each protocol in order to develop an integrated protocol capable of giving victims a better and more successful future.

7 Conclusion

The results of this study showed that the services provided by PH met the expectations of the victims. Although victims admitted to PH had varying expectations and needs based on their social identity and residence locations, they all expected physical and psychological restoration as well as socioeconomic reintegration and legal assistance. We found with scores above 4 that the victims of sexual violence were extremely satisfied with the overall care provided by the One Stop Centre model. The non-parametric analysis of the rank means comparison revealed that the level of satisfaction varied according to sociodemographic factors. Victims from South Kivu's rural areas reported 39% satisfaction with legal assistance. Teenagers and young adults were less satisfied than older women. Christian women (Protestants and Catholics) are more satisfied with ergotherapy than women of other religious communities. Students and farmers were delighted with the accommodation’s possibilities offered by PH. They wished to continue being supported to escape their misery after discharge. Therefore, additional efforts should be made to improve the quality of care according to this holistic model. It is essential to assess the level of beneficiary satisfaction using psychological satisfaction scales (e.g., the Life Satisfaction Scale developed by American psychologist Ed Diener) and participatory methods and techniques to ensure that Panzi's actions achieve the desired results.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon email request from the corresponding author.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- DRC:

-

Democratic Republic of Congo

- HIC:

-

High-Income Countries

- LIC:

-

Low-Income Countries

- OSC:

-

One Stop Center

- PH:

-

Panzi Hospital

- PREM:

-

Patient-Reported Experience Measure

- PROM:

-

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measure

- SGBV:

-

Sexual and gender-based violence

References

Bogren M, Erlandsson K, Akter HA, Khatoon Z, Chakma S, Chakma K, et al. What prevents midwifery quality care in Bangladesh? A focus group enquiry with midwifery students. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):639.

Parameswaran SG, Spaeth-Rublee B, Pincus HA. Measuring the quality of mental health care: consensus perspectives from selected industrialized countries. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2015;42(3):288–95.

OECD, World Health Organization. Improving Healthcare Quality in Europe: Characteristics, Effectiveness and Implementation of Different Strategies [Internet]. OECD; 2019 https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/improving-healthcare-quality-in-europe_b11a6e8f-en. Accessed 3 Jul 2022.

de Bienassis K, Kristensen S, Hewlett E, Roe D, Mainz J, Klazinga N. Measuring patient voice matters: setting the scene for patient-reported indicators. Int J Qual Health Care. 2022;34(Supplement_1):ii3-6.

Caswell RJ, Ross JD, Lorimer K. Measuring experience and outcomes in patients reporting sexual violence who attend a healthcare setting: a systematic review. Sex Transm Infect. 2019;95(6):419–27.

Wolff AC, Dresselhuis A, Hejazi S, Dixon D, Gibson D, Howard AF, et al. Healthcare provider characteristics that influence the implementation of individual-level patient-centered outcome measure (PROM) and patient-reported experience measure (PREM) data across practice settings: a protocol for a mixed methods systematic review with a narrative synthesis. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):169.

Kerak E, Barrijal S. Modèle de mesure et d’évaluation de la qualité des services offerts par les organismes gestionnaires d’assurance maladie au Maroc. AORT: Prat Organ Soins. 2010;41(3):215–24.

Bougmiza I, Ghardallou MEL, Zedini C, Lahouimel H, Nabli-Ajmi T, Gataa R, et al. Evaluation de la satisfaction des patientes hospitalisées au service de gynécologie obstétrique de Sousse Tunisie. Pan Afr Med J. 2011. https://doi.org/10.4314/pamj.v8i1.71161.

Cabrera-Barona P, Blaschke T, Kienberger S. Explaining accessibility and satisfaction related to healthcare: a mixed-methods approach. Soc Indic Res. 2017;133(2):719–39.

Barbosa CD, Balp MM, Kulich K, Germain N, Rofail D. A literature review to explore the link between treatment satisfaction and adherence, compliance, and persistence. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:39–48.

Blödt S, Müller-Nordhorn J, Seifert G, Holmberg C. Trust, medical expertise and humaneness: a qualitative study on people with cancer’ satisfaction with medical care. Health Expect. 2021;24(2):317–26.

Nyandwe J, Mapatano M, Lussamba P, Kandala NB, Kayembe P. Measuring patients’ perception on the quality of care in the democratic republic of congo using a modified, service quality scale (SERVQUAL). Arch Sci. 2017;1(2):1000108.

Yamba KMY, Désiré K, Mashinda JMN. Evaluation de la qualité des soins aux Cliniques Universitaires de Kinshasa: étude de satisfaction des patients hospitalisés. Ann Afr Med. 2018;11(3):2931–2.

Wolomby-Molondo J, Calvert C, Seguin R, Qureshi Z, Tunçalp Ö, Filippi V. The relationship between insecurity and the quality of hospital care provided to women with abortion-related complications in the Democratic Republic of Congo: a cross-sectional analysis. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2022;156(S1):20–6.

Clarke-Deelder E, Shapira G, Samaha H, Fritsche GB, Fink G. Quality of care for children with severe disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1608.

Karemere H, Mukwege J, Molima C, Makali S. Analysis of hospital performance from the point of view of sanitary standards: study of Bagira General Referral Hospital in DR Congo. J Hosp Manag Health Policy. 2020;4(9):1–44.

Yameogo AR, Millogo GRC, Palm AF, Bamouni J, Mandi GD, Kologo JK, et al. Évaluation de la satisfaction des patients dans le service de cardiologie du CHU Yalgado Ouedraogo. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;28:267.

Vandenberghe A, Hendriks B, Peeters L, Roelens K, Keygnaert I. Establishing Sexual Assault Care Centres in Belgium: health professionals’ role in the patient-centred care for victims of sexual violence. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):807.

Norbu N, Zam K. Assessment of health-sector response to gender-based violence at different levels of health facilities in Bhutan (2015–2016). World Med Health Policy. 2021;13(4):653–74.

Bovier P, Künzi B, Stalder H. Qualitédes soins en médecine de premier recours:«à l’écoute de nos patients». Rev Med Suisse. 2006;2:2176–81.

Bouvier P. Sexual violence, health and humanitarian ethics: Towards a holistic, person-centred approach. Int Rev Red Cross. 2014;96(894):565–84.

WHO. Responding to Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Violence Against Women: WHO Clinical and Policy Guidelines. World Health Organization; 2013. 66 p.

WHO, UNODC. Strengthening the medico-legal response to sexual violence [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2015. Report No.: WHO/RHR/15.24. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/197498. Accessed 20 Oct 2022.

Peeters L, Vandenberghe A, Hendriks B, Gilles C, Roelens K, Keygnaert I. Current care for victims of sexual violence and future sexual assault care centres in Belgium: the perspective of victims. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2019;19(1):21.

Mukwege D, Berg M. A Holistic, Person-Centred Care Model for victims of sexual violence in Democratic Republic of Congo: The Panzi Hospital one-stop centre model of care. PLOS Med. 2016;13(10): e1002156.

Pajnkihar M, Štiglic G, Vrbnjak D. The concept of Watson’s carative factors in nursing and their (dis)harmony with patient satisfaction. PeerJ. 2017;7(5): e2940.

WHO. Clinical management of rape and intimate partner violence survivors: developing protocols for use in humanitarian settings. 2020;

Beard AS, Candy AE, Anderson TJ, Derrico NP, Ishani KA, Gravely AA, et al. Patient satisfaction with medical student participation in a longitudinal integrated clerkship: a controlled trial. Acad Med. 2020;95(3):417–24.

Lairy G. La satisfaction des patients lors de leur prise en charge dans les établissements de santé. Rev Litterature Medicale ANAES. 1996;

Mendoza Aldana J, Piechulek H, Al-Sabir A. Satisfaction des patients et qualité des soins dans les zones rurales du Bangladesh. Bull Organ Mond Santé Recl Artic. 2001;2001(5):65–70.

Mukwege DM, Nangini C. Rape with extreme violence: the new pathology in South Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo. PLoS Med. 2009;6(12): e1000204.

Olson RM, García-Moreno C, Colombini M. The implementation and effectiveness of the one stop centre model for intimate partner and sexual violence in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review of barriers and enablers. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(3): e001883.

Bovier P, Haller D, Lefebvre D. Mesurer la qualité des soins en médecine de premier recours: difficultés et solutions. Médecine Hygiène. 2004;62:1833–5.

Davis SL, Schopper D, Epps J. Monitoring interventions to respond to sexual violence in humanitarian contexts. Glob Health Gov. 2018;12(1):34.

Chimatiro GL. Stroke patients’ outcomes and satisfaction with care at discharge from four referral hospitals in Malawi: a cross-sectional descriptive study in limited resource. Malawi Med J. 2018;30(3):152–8.

Leganet. LOI N° 16/008 DU 15 juillet 2016 modifiant ET COMPLETANT LA LOI N°87–010 du 1er AOUT 1987 PORTANT [Internet]. 2016. https://www.leganet.cd/Legislation/Code%20de%20la%20famille/Loi.15.07.2016.html.Accessed 20 Oct 2022.

Kelly L. Combating violence against women: minimum standards for support services. 2008;

Mkhize N. Sexual violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo armed conflict: testing the AU and EU protocols. J Public Adm Dev Altern JPADA. 2020;5(3):62–75.

Komar D, El Jundi S, Parra RC, Perich P. A comparison of the international protocols for the forensic assessment of conflict-related sexual violence victims. J Forensic Sci. 2021;66(4):1520–3.

Poulet N. Information du patient et consentement éclairé en matière médicale. Trayectorias Humanas Trascontinentales. 2018. https://doi.org/10.25965/trahs.1174.

Senić V, Marinković V. Patient care, satisfaction and service quality in health care: patient care, satisfaction and service quality in health care. Int J Consum Stud. 2013;37(3):312–9.

Thimmapur RM, Raj P, Raju B, Kanmani TR, Reddy NK. Caregivers satisfaction with intensive care unit services in tertiary care hospital. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2018;8(4):184–7.

Ofei-Dodoo S. Patients satisfaction and treatment outcomes of primary care practice in Ghana. Ghana Med J. 2019;53(1):63.

Shanks L, Schull MJ. Rape in war: the humanitarian response. CMAJ. 2000;163(9):1152–6.

Marsh M, Purdin S, Navani S. Addressing sexual violence in humanitarian emergencies. Glob Public Health. 2006;1(2):133–46.

Batbaatar E, Dorjdagva J, Luvsannyam A, Savino MM, Amenta P. Determinants of patient satisfaction: a systematic review. Perspect Public Health. 2017;137(2):89–101.

Ajavon DRD, Kakpovi K, Daketse YMS, Ketevi AA, Douaguibe, Logbo-Akey KE, et al. Evaluation De La Satisfaction Des Patientes Hospitalisées En Suites De Couches À La Maternité De L’hôpital De Bè (Togo). Eur Sci J ESJ. 2021. https://doi.org/10.19044/esj.2021.v17n29p210.

Mutabunga FL, Chenge FM, Criel B, MukalaY A, Luboya O, Tshamba HM. Micro assurance santé comme levier financier à l’accès aux services de santé de qualité en RD Congo: Défis, Pistes des Solutions et Perspectives. Int J Multidiscip Curr Res. 2017;5:618–33.

Aroussi S. Perceptions of justice and hierarchies of rape: rethinking approaches to sexual violence in Eastern Congo from the Ground up. Int J Transitional Justice. 2018;12(2):277–95.

Finnbakk I, Nordas R. Community perspectives and pathways to reintegration of survivors of sexual violence in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Hum Rts Q. 2019;41:263.

Stark L, Seff I, Reis C. Gender-based violence against adolescent girls in humanitarian settings: a review of the evidence. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5(3):210–22.

Anderson GD, Overby R. Barriers in seeking support: perspectives of service providers who are survivors of sexual violence. J Community Psychol. 2020;48(5):1564–82.

Perrin N, Marsh M, Clough A, Desgroppes A, Yope Phanuel C, Abdi A, et al. Social norms and beliefs about gender based violence scale: a measure for use with gender based violence prevention programs in low-resource and humanitarian settings. Confl Health. 2019;13(1):6.

Wemmers JA, Parent I, Casoni D, Lachance Quirion M. Les expériences des victimes de violence sexuelle dans les programmes de justice réparatrice. Montr QC Cent Int Criminol Comparée. 2020;

Denis I, Brennstuhl MJ, Tarquinio C. Les conséquences des traumatismes sexuels sur la sexualité des victimes : une revue systématique de la littérature. Sexologies. 2020;29(4):198–217.

LeBlanc S. Intervenir auprès de jeunes victimes de violence sexuelle au Sud-Est du Nouveau-Brunswick, Boreal : Centre d’expertise pour enfants et adolescents. Reflets Rev D’intervention Soc Communaut. 2020;26(1):121.

Smith JR, Ho LS, Langston A, Mankani N, Shivshanker A, Perera D. Clinical care for sexual assault survivors multimedia training: a mixed-methods study of effect on healthcare providers’ attitudes, knowledge, confidence, and practice in humanitarian settings. Confl Health. 2013;7(1):14.

Amisi C, Apassa RB, Cikara A, Østby G, Nordås R, Rustad SA, et al. The impact of support programmes for survivors of sexual violence: micro-level evidence from eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Med Confl Surviv. 2018;34(3):201–23.

Veit A, Tschörner L. Creative appropriation: academic knowledge and interventions against sexual violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo. J Interv Statebuilding. 2019;13(4):459–79.

Bitenga A. Hidden survivors of sexual violence: challenges and barriers in responding to rape against men in Eastern DRC. 2021.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to Panzi Hospital team caring for the victims of sexual violence and to all the abused women who agreed to participate in this study.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: GMM, RM, SN; Methodology: GMM, RM, ACK, AB; Formal analysis and investigation: GMM, RM, SN, ACK, AB; Writing—original draft preparation: GMM, RM; Writing—review and editing: GMM, RM, ACK, AB; Supervision: DM. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol of this study was approved by the National Ethics Committee for Health Studies (CNES 001/DPSK/182PM/2021). Respondents had to sign the informed consent before starting the survey and the interview.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mugisho, G.M., Maroyi, R., Nabami, S. et al. Sexual and gender-based violence victims’ satisfaction of the support services through the holistic model of care in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Discov Soc Sci Health 2, 22 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44155-022-00025-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44155-022-00025-x