Abstract

A patients’ increasing interest in dietary modifications as a possible complementary or alternative treatment of endometriosis is observed. Unfortunately, the therapeutic potential of dietary interventions is unclear and to date no guidelines to assist physicians on this topic exist. The aim of this study, therefore, was to systematically review the existing studies on the effect of dietary interventions on endometriosis. An electronic-based search was performed in MEDLINE and COCHRANE. We included human and animal studies that evaluated a dietary intervention on endometriosis-associated symptoms or other health outcomes. Studies were identified and coded using standard criteria, and the risk of bias was assessed with established tools relevant to the study design. We identified nine human and 12 animal studies. Out of the nine human studies, two were randomized controlled trials, two controlled studies, four uncontrolled before-after studies, and one qualitative study. All of them assessed a different dietary intervention, which could be classified in one of the following principle models: supplementation with selected dietary components, exclusion of selected dietary components, and complete diet modification. Most of the studies reported a positive effect on endometriosis; they were however characterized by moderate or high-risk bias possibly due to the challenges of conducting dietary intervention trials. According to the available level of evidence, we suggest an evidence-based clinical approach for physicians to use during consultations with their patients. Further well-designed randomized controlled trials are needed to accurately determine the short-term and long-term effectiveness and safety of different dietary interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Endometriosis and Current Therapeutic Limitations

Endometriosis, characterized by the growth of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterine cavity, is an estrogen-dependent chronic inflammatory highly prevalent gynecological disorder of reproductive-aged women worldwide [1,2,3]. It is a significantly heterogeneous disease, both in phenotype and clinical outcomes that vary from no symptoms to severe pain and/or subfertility leading to a significant reduction in quality of life [4, 5]. Moreover, the economic impact is substantial, as chronic and debilitating pain from endometriosis may hinder work productivity, while infertility can cause major psychosocial and financial strain to affected women and their partners [6].

Treatment options are either hormonal-based therapies or laparoscopic surgical excision of the endometriotic lesions. According to current guidelines, endometriosis-related pain should be empirically treated with adequate analgesia and combined oral contraceptives or progestins prior to a definitive diagnosis [7]. Unfortunately, adjuvant hormonal therapy is often accompanied by significant, unwanted side effects and in about 30% of the patients a non-adequate reduction in endometriosis-associated pain [8]. In another recent study, 45.4% of the patients have been reported to be unsatisfied with their medical treatment [9] while high treatment discontinuation rates have been observed [10]. As a result, many patients will undergo laparoscopic excision of endometriosis, which is associated with decreased overall pain, both at 6 and 12 months after surgery as well as fertility improvement in some cases [11, 12]. However, even after a complete removal of endometriotic lesions a high proportion of patients will require additional surgery due to endometriosis recurrence with total recurrence rates of 21.5% and 40–50% at 2 and 5 years, respectively [13,14,15,16,17]. To avoid disease, recurrence postoperative adjuvant hormonal therapy is advised until planning a pregnancy [18, 19].

Given the above and considering that these therapeutic options are non-curative and may not align with women’s reproductive goals, it becomes apparent that there is an unmet need for improved treatment of endometriosis and associated symptoms.

Nutrition and Risk of Endometriosis: Dietary Intervention Possible?

Nutrition is widely recognized as a prognostic and modifiable factor related to morbidity and life expectancy [20,21,22,23]. Several observational studies have investigated certain nutrition habits as risk factors for endometriosis [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. Women with endometriosis seem to consume fewer vegetables, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, and dairy products and more red meat, coffee, and trans fats; but these findings could not be consistently replicated [39]. A recent review summarizing the linkage between diet end endometriosis underlined the potential of anti-inflammatory components present in foods to mitigate endometriosis [40]. However, to date, no study has reviewed the therapeutic potential of dietary interventions in patients with already diagnosed endometriosis. As complementary therapies and self-management for women with endometriosis including dietary modifications become more widely popular, it is important to ensure their safety and effectiveness.

Our study, therefore, aimed to conduct a systematic review of the literature investigating the effect of dietary interventions on endometriosis. We intended to cover the literature on a number of sub-questions, including (a) if a certain subcategory of patients are more likely to benefit from a dietary intervention or (b) if specific dietary interventions ameliorate certain symptoms while others remain unchanged.

Materials and Methods

This systematic review was prepared according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA-P Statement). The study protocol was registered in the Bern Open Repository and Information System (BORIS) of the University of Bern under the number 143339.

Search Strategy

The electronic medical information database Medline was searched up to 30. April 2020 with the following search algorithm: (endometriosis) AND ((diet*) OR (nutrition) OR (fasting)). The same keywords were used to search the Cochrane library. No filter or limitation was applied. Reference lists from selected studies were manually scanned to identify any other relevant studies.

Eligibility Criteria

Original studies (cohort, case-control, and randomized controlled studies) including women diagnosed with endometriosis or animals with induced endometriosis assessing a dietary intervention on endometriosis-associated symptoms or other health outcomes were included. Possible dietary interventions were either adherence to a specific diet or intake of dietary supplements. Studies that did not present the dietary patterns, case reports, and conference abstracts as well as studies including patients with dysmenorrhea without the diagnosis of endometriosis and in vitro studies were excluded.

Outcomes

Changes in endometriosis-associated symptoms measured with pain scales or patient reported quality of life outcomes. Regression of endometriosis is either reported by imaging examinations or a decrease of endometriosis-associated biomarkers. Change of other relevant health outcomes.

Data Extraction

Titles and abstracts were evaluated independently by two reviewers. Any discrepancy was resolved by consensus. Data extraction was performed by the same two reviewers. For each study, information on publication data, study design, population characteristics, type of dietary intervention, results, and limitations were extracted.

A narrative synthesis of the data was applied to compare the effects of different dietary interventions on the outcomes and a meta-analysis was initially planned.

Risk of Bias Assessment

The different types of bias assessment were performed independently by more than one investigator (KN, KE, and DRK for the human studies and KE and DRK for the animal studies). Quality assessment for observational human studies was performed by the Quality in Prognostic Studies (QUIPS) tool and for animal studies with the SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool (doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-43). Risk judgment was assessed using pre-specified study criteria. For randomized controlled trials, five criteria of the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool were used ((selection bias (random sequence generation and allocation concealment); performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel); detection bias (blinding of outcome assessors); attrition bias (incomplete outcome data); reporting bias (selective reporting)) [41, 42].

Results

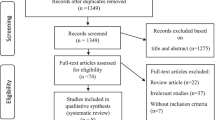

A total of 318 studies were identified and screened for inclusion. After excluding 287 studies by reading the titles and abstracts, 31 studies were further assessed for eligibility of which 10 further articles were excluded due to study design and outcome measurements. At the end, nine human and 12 animal studies were included (Fig. 1).

Human Studies

Out of the nine human studies, two were randomized controlled trials [43, 44], two prospective controlled studies [45, 46], two prospective [47, 48], and two retrospective [49, 50] uncontrolled before-after studies and one qualitative study [51]. The follow-up period of studies ranged from 4 weeks to 12 months. Studies were from Italy (n = 3), Austria (n = 1), Sweden (n = 1), Australia (n = 1) Mexico (n = 1), and Iran (n = 1).

Interventions comprised of supplementation of vitamin D [43]; supplementation of vitamins A, C, and E [46]; supplementation of omega-3/6; quercetin; vit B3; 5-methyltetrahydrofolate calcium salt, turmeric, and parthenium [45]; Mediterranean diet [48]; low-FODMAP diet [49]; low nickel diet [47]; gluten-free diet [50]; and individual diet changes [51]. The detailed characteristics of the human studies and the risk of bias assessment are presented in Tables 1, 2, and 3.

Uncontrolled Before-After Studies

One retrospective before-after study conducted in Italy and published in 2012 [50] investigated the effect of the gluten-free diet in 295 patients with moderate or severe endometriosis-associated symptoms. Two weeks after starting the diet, 88 (30%) patients withdrew due to side effects as abdominal symptoms. At 12 months of follow-up, 156 patients reported a statistically significant change from baseline in painful symptoms while 51 patients reported no improvement. Moreover, the scores in measurements of quality of life were significantly increased. The same group from Italy presented an oral communication in a congress in 2015 investigating retrospectively the gluten-free diet in a case-control study including 300 patients with endometriosis. Both groups were subjected to dienogest therapy (2 mg/day) while the case group received a gluten-free diet. The data showed a statistically significant improvement of pelvic pain in the group of patients with gluten-free diet. Since this study was never published in a peer-review journal, it was excluded from our further analysis [52].

In a retrospective analysis of a cohort study assessing the efficacy of a diet low in fermentable oligo-, di-, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAP) in 160 patients with irritable bowel syndrome, responses in patients with (N = 59) and without (n = 101) endometriosis were contrasted. FODMAPs are poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates that are readily fermentable by bacteria. Their osmotic actions and gas production may cause intestinal luminal distension inducing pain and bloating in patients with visceral hypersensitivity with secondary effects on gut motility. Adherence to the diet was high in both groups with only four (7%) in the endometriosis group and ten (9%) in those without endometriosis showing insufficient compliance to assess efficacy. Forty-three (72%) of the patients with endometriosis experienced an improvement of symptoms over 50% after following this diet for 4 weeks. This was significantly higher than in the group of patients without endometriosis and represented a threefold increase in the likelihood of responding to the low-FODMAP diet compared to those without known endometriosis (OR 3.11, 95% CI 1.5–6.2) [49].

The prevalence of nickel allergic contact mucositis (Ni ACM) in patients with endometriosis and gastrointestinal disorders was evaluated in a recent Italian study. Forty-seven patients were included out of which 31 (70%) adhere to the suggested balanced low-Ni diet for 3 months. Twenty-eight out of the 31 patients studied (90.3%) showed oral mucosal patch test positive results. All gastrointestinal symptoms measured by the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) questionnaire (p < 0.05) as well as dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and pelvic pain measured by a numeric scale (0–10) (p < 0.005) showed a statistically significant decrease in intensity [47].

The influence of the Mediterranean diet on endometriosis-associated pain was examined in a single-arm study in Austria. Sixty-eight women with a previous laparoscopic diagnosis of endometriosis and postoperative endometriosis–associated pain were included. Patients had to adhere to a specific nutrition plan regimen including fresh vegetables, fruit, white meat, fish rich in fat, soy products, whole meal products, foods rich in magnesium, and cold-pressed oils. During the intervention, participants were asked to avoid sugary drinks, red meat, sweets, and animal fats. Pain degrees were specified on a Numeric Rating Scale (NRS). Twenty-five study participants (36.8%) did not adhere to the recommended dietary regimen due to pregnancy or change to classical treatment options. However, in an intention-to-treat analysis, all 68 patients were included. A significant relief of general pain, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and dyschezia as well as an improvement in the general condition was found [48].

Controlled Studies

In a Mexican case-control study, 82 infertile patients with rASRM stages I–II endometriosis were randomly assigned either to a control group with normal diet (n = 37) or to a high antioxidant diet (HAD) group (n = 35) for 4 months according to each patient’s energy requirements. Adherence to the diet was high in both groups with 32 (91.4%) in the HAD and 34 (91.9%) in the normal diet group completing the study. An increase in the vitamin concentrations (serum retinol, alpha-tocopherol, leukocyte, and plasma ascorbate) and antioxidant enzyme activity (superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase) as well as a decrease in oxidative stress markers (malondialdehyde and lipid hydroperoxides) were observed in the HAD group after 2 months of intervention. These phenomena were not observed in the control group. No clinical outcomes were examined in this study [46].

In an Italian placebo-controlled study, 90 laparoscopically diagnosed rASRM stage IV endometriosis patients were split into three groups. All of the patients had to increase the daily fiber intake by 20–30% and food containing omega 3. Moreover, the patients were asked to reduce the consumption of dairy products (by at least 30%), meat (by at least 50%), gluten-rich food, caffeine, alcohol, chocolate, saturated fat, butter, and margarine. Finally, the consumption of soy, aloe, and oats for all the observation was forbidden. Additionally to that, the first group was treated with a composition of dietary supplements (alpha linolenic acid (omega 3), linoleic acid (omega 6), quercetin, nicotinamide, 5-methyltetrahydrofolate calcium salt, titrated turmeric, and titrated parthenium)). The second group was treated with linseed oil and 5-methyltetrahydrofolate calcium salt and the third group with placebo. The study demonstrated a significant reduction of pain symptoms and serum levels of PGE2, 17b-estradiol, and CA-125 in the first group after 3 months. The authors concluded that the data indicated an anti-inflammatory action of the compounds that mimic the pharmacological action of the most common used drugs for the therapy of endometriosis [45].

In a randomized controlled trial conducted in Iran 40 patients with persistent pain at second menses after operative laparoscopy were double-blind randomized to receive either vitamin D (50,000 iu/weekly) or placebo for 12 weeks. The majority of the patients had rASRM stage III or IV endometriosis (87.5%). The severity of dysmenorrhea and pelvic pain was measured by the VAS test. No significant effect of vitamin D on the pain outcomes 24 weeks after laparoscopy was shown [43].

Another randomized controlled trial conducted in Italy [44] randomized patients with rASRM stages III–IV endometriosis at the time of postoperative control to placebo (n = 115), GnRHa (n = 40), continuous COC (n = 40), and nutritional supplements (vitamins (B6, A, C, E), mineral salts (Ca, Mg, Se, Zn, Fe), lactic ferments, fish oil (omega-3/6)) for 6 months. Dysmenorrhoea, non-menstrual pain, deep dyspareunia, and quality of life was measured preoperatively and at 12 months’ follow-up. Patients treated with hormonal suppression showed less visual analogue scale scores for dysmenorrhoea than patients of the other groups. Hormonal suppression therapy and dietary supplementation were equally effective in reducing non-menstrual pelvic pain. A significative decrease in dyspareunia scores was observed in the controls than in patients randomly allocated to other postoperative adjunctive therapies. Finally, a considerable increase of scores for all domains of SF-36 was observed in all women at 12 months’ follow-up, independently by the treatment randomly assigned.

Qualitative Studies

The most recent study on dietary changes in endometriosis is a qualitative interview study in which semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted with 12 patients with endometriosis who had made individual dietary changes aimed at decreasing their endometriosis symptoms. The patients were asked about the dietary changes they made and changes in symptom severity after being recruited from two Swedish endometriosis support forums on the internet. The participants experienced an increase in well-being and a decrease in symptoms following their dietary and lifestyle changes. They also felt that the dietary changes led to increased energy levels and a deeper understanding of how they could affect their health by listening to their body’s reactions. No objective pain measurements were performed [51].

Quality and Publication Bias Assessment in Human Studies

One RCT in this systematic review was assessed as a low risk bias study. It is, however, worth mentioning that with the inclusion of only 20 patients per group this trial was substantially underpowered to detect a significant difference. The second RCT included in the analysis was also assessed as a low-risk bias study. However, a high risk in attrition bias was given due to exclusion of lost to follow-up patients from the statistical analysis although this was the case for only 5.1% of the patients.

None of the observational studies were assessed as “low risk” of bias studies since they all received at least one high or moderate risk of bias in the pre-specified criteria according to the QUIPS tool. The only study receiving no high-risk bias assessment in any of the QUIPS categories was the study by Ott et al. [48]. The study of Vennberg et al. [51] was assessed as a high-risk bias study due to many methodological shortcomings. Participants were asked to talk freely about their changed nutritional habits; however, these were not systematically described. Moreover, the outcome of the study was not provided and endometriosis-associated symptoms were not quantified. The statistical analysis and reporting in the study by Moore et al. [49] received a high-risk bias rating because only the proportion of patients with “response” to the diet but not their VAS scores was presented. Signorile et al. did not report the number of participants lost to follow-up and the data were presented as percentage of patients with VAS score > 5. The study by Mier-Cabrera J. et al. [46] received a high-risk bias rating in study confounding since patients were assigned to the dietary intervention or normal diet according to the previous vitamin intake measurements so that the case groups was substantially different and not comparable to the control group. Moreover, only laboratory markers and no direct endometriosis-associated outcomes were measured which lowers the interpretability of the results. Finally, the study by Borghini et al. [47] and Marziali et al. [50] experienced a dropout rate of approximately 30%. The statistical analysis and reporting risk were deemed high since no intention to treat analysis was performed.

Animal Studies

The 12 included animal studies were published between 2007 and 2018. All of them used a mouse model for endometriosis. Six studies performed the method of autotransplantation of uterine tissue to peritoneum [53,54,55,56,57,58], three studies used endometrial tissue from endometriosis-free women and implanted it to the abdominal cavity [59,60,61], one study used eutopic endometrial tissue from women with endometriosis [62] and two other studies transplanted the uterus from a donor mice [63, 64]. In two studies, the mice underwent overectomy [56, 60]. The study interventions were either dietary supplementations or caloric intake modifications. The detailed study characteristics are presented in Table 4 and the risk of bias assessment in Table 5.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review of the effect of dietary interventions in patients with endometriosis. Given the high possibility of these patients to seek complementary therapies including dietary modulations [65,66,67] as well as the recently established multidisciplinary programs involving dieticians in most endometriosis centers [68], it becomes urgent that the up-to-date evidence to guide clinical practice is presented. Although a meta-analysis was impossible due to the high heterogeneity of the interventions and measured outcomes, the study provides a thorough overview of the published studies on this topic. The review identified nine human studies all of which assessed a different dietary intervention with most of them finding a positive effect on endometriosis. However, all studies are characterized by moderate and/or high-risk bias limiting the validity of the results.

Results in the Context of What is Known

The association between vitamin D levels and endometriosis remains unclear to date [69]. In the current review, the only study showing no positive effect of the dietary intervention on endometriosis was an RCT exploring vitamin D supplementation in patients with unknown serum vitamin D levels. Another RCT with the same sample size including patients with primary dysmenorrhea and vitamin D insufficiency but no endometriosis has previously shown a positive effect of vitamin D on pain (standardized mean difference − 1.02; 95% CI − 1.9 to 0.14; P = 0.024) [70]. A significantly greater mean decrease in pain has been also observed in a systematic meta-analysis evaluating vitamin D supplementation in patients with several pain disorders (mean difference − 0.57; 95% CI − 1.00 to − 0.15; P = 0.007) [71]. It is however obvious that the results of these studies cannot be extrapolated to the general endometriosis population so that vitamin D supplementation cannot be currently recommended in patients with endometriosis unless there is a documented vitamin D deficiency. We identified one trial protocol aiming to investigate the supplementation of vitamin D3 in adolescent girls with endometriosis, which was completed in 2016 but since then no data were published [72].

Three studies included in the current review investigated the role of an antioxidant supplementation. This included specific vitamins, fish oils, and mineral salts with different protocols in each study. A significant reduction of symptoms was observed in two of the studies one of which was a randomized controlled trial [44, 45]. The third study only measured blood oxidative stress markers, which were found to be decreased after dietary intervention [46]. Finally, one study conducted in the USA was published only as an abstract in 2003 and thus excluded from the qualitative synthesis [73]. Nevertheless, the study investigated the effect of vitamin E and vitamin C supplementation for 2 months on inflammatory markers in women with endometriosis. A decrease in all the inflammatory markers (MCP-1, RANTES, IL-6) in the peritoneal fluid was seen according to the results in the abstract. Overall, based predominantly on the available RCT, it seems that this type of dietary interventions may have the potential to ameliorate endometriosis-associated pain. Currently, there are four registered protocols for clinical trials on this type of dietary supplementations [74,75,76,77].

The study by Ott et al. [48] could also be included in the above category since the suggested Mediterranean diet has well-known antioxidant effects. However, the Mediterranean diet does not involve just the supplementation of certain antioxidants, but rather a collection of eating habits and may thus improve endometriosis-associated pain via additional mechanisms. Fish as well as extra virgin olive oils have been shown to exert anti-inflammatory effects. Specifically, extra virgin olive oil, which contains the substance oleocanthal, displays a similar structure to the molecule ibuprofen, and both take effect via the same mechanism, i.e., cyclooxygenase inhibition. Moreover, the increased amount of fibers provides a eupeptic effect while foods high in magnesium could prevent an increase in the intracellurar calcium level and advance the relaxation of the uterus [78]. Taking into account the lack of risks or side effects even after long-term lifetime adherence to this diet and the possible other general health benefits [20, 22, 23] clinicians may suggest this type of dietary intervention to patients with endometriosis who wish to change their nutritional habits. Two protocols for clinical trials are currently registered with the one investigating the effect of Mediterranean diet and physical activity [79] and the other the Alternative Healthy Eating Index diet [80] in patients with endometriosis.

The other category of dietary interventions in this review consists of diets excluding or reducing specific substances such as gluten-free, low-Ni, and low-FODMAP diet. Two studies included only patients with endometriosis and gastrointestinal symptoms [47, 49] while the third one patients with endometriosis in general [50]. All studies showed an improvement of symptoms in at least 70% of the patients adhering to the diet. However, interestingly, in the gluten-free and low-Ni diet, approximately 30% of the patients did not adhere to the diet while no intention-to-treat analysis was performed. In the low-FODMAP diet, a higher adherence was observed maybe due to the shorter time of the intervention (4 weeks) or the exclusive inclusion of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Because of FODMAPs’ characteristic of insufficient absorption and their consecutive fermentation by bacteria, their gas production tends to cause abdominal intestinal extension that may lead to pain and modification of gut motility. Diseases like irritable bowel syndrome and endometriosis come along with visceral hypersensitivity, implementing the hypothesis of symptom-reduction after sticking to a low-FODMAP diet [81, 82]. This is very important given the high prevalence of gastrointestinal-related symptoms and co-morbidities in patients with endometriosis [83, 84]. Interestingly, the low-FODMAP diet includes not only a low-Ni diet, but also a low-lactose and a low-gluten diet, thus covering the abovementioned diets and a large spectrum of high-prevalence pathologies, such as lactose intolerance and non-celiac gluten sensitivity. It is therefore possible to obtain clinical benefits from a low-FODMAP diet, even if at the cost of probably not necessary dietary exclusions. Prospective studies with low-FODMAP diets in patients with endometriosis with clear description of their symptoms and co-morbidities are needed to elucidate this issue. We identified one registered protocol for a pilot clinical trial on the effects of low-FODMAP diet on endometriosis-related gastrointestinal symptoms, which should be completed by February 2018 but not yet published [85].

The aim of this review was to evaluate the role of dietary interventions in patients with previously diagnosed endometriosis. Many studies on the effects of dietary supplements on dysmenorrhea exist though. Dysmenorrhea is the most common symptom in endometriosis but it is also highly non-specific so that dysmenorrhea does not necessitate the existence of endometriosis. Nevertheless, the existing evidence is worth mentioning. The most recent Cochrane systematic review concluded that there is very limited evidence of effectiveness for fenugreek (MD − 1.71 points; 95% CI − 2.35 to − 1.07; one RCT, 101 women), fish oil (MD 1.11 points; 95% CI 0.45 to 1.77; one RCT, 120 women), fish oil plus vitamin B1 (MD − 1.21 points; 95% CI − 1.79 to − 0.63; one RCT, 120 women), ginger (MD − 1.55 points; 95% CI − 2.43 to − 0.68; three RCTs, 266 women; OR 5.44; 95% CI 1.80 to 16.46; one RCT, 69 women), valerian (MD − 0.76 points; 95% CI − 1.44 to − 0.08; one RCT, 100 women), vitamin B1 (MD − 2.70 points; 95% CI − 3.32 to − 2.08; one RCT, 120 women), zataria (OR 6.66, 95% CI 2.66 to 16.72; one RCT, 99 women), and zinc sulphate (MD − 0.95 points; 95% CI − 1.54 to − 0.36; one RCT, 99 women) [86]. In the same Cochrane review, one RCT was included evaluating melatonin in patients with endometriosis [87]. The study authors reported that melatonin reduced dysmenorrhea and daily pain scores. However, this study was excluded from our review since the administration of melatonin cannot be considered as a dietary intervention but more as a hormonal treatment.

The animal studies included in this review present promising results that need confirmation in human studies. Interestingly, a high-fat diet intake increased the number of the endometriosis lesions [64] while caloric restriction leaded to a reduced endometriosis lesion weight [63]. Moreover, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) were shown to induce the regression of endometriosis [54, 56, 58], which is partially in line with the human studies. Finally, several natural components found in plants such as resveratrol (natural phenol found in grapes and red wine) [60], quercetin (a plant flavonol) [55], xanthohumol (found in beer) [53], and epigallocatechingallate (found in green tea) [62] seem to inhibit endometriosis. However, due to the way of inducing endometriosis in animals, the route of nutrition administration in some studies and the lack of symptom measurement, all of which do not reflect the reality in humans, the results of the animal studies cannot be extrapolated to changes in the patients’ diet.

Implications for Practice

As presented above, only a small number of studies to date have examined dietary modifications to treat endometriosis and endometriosis-associated symptoms. A high study heterogeneity was identified and all studies are characterized by moderate or high-risk bias. Although most studies reported a positive effect of the intervention on endometriosis, we could not clearly identify certain subcategories of patients, which are more likely to benefit from a dietary intervention nor did we identify specific dietary interventions, which ameliorate certain endometriosis-associated symptoms. More and higher quality original studies are urgently needed to enable safe conclusions on this topic. Until then, we suggest a possible clinical approach to the patient with endometriosis seeking a dietary change to treat her symptoms (Fig. 2). Based on the promising results of the prospective before-after study by Ott et al. [48] as well as considering the well-known health benefits and no risks of Mediterranean diet, physicians may suggest this diet as a long-term dietary change. However, due to the difficulty in adhering to Mediterranean diet related to the costs, cooking habits, and personal daily life, a supplementary antioxidant diet may be considered for up to 6 months based on the RCT by Sesti et al. [44]. A longer than 6 months intake of dietary supplements cannot be suggested due to the unclear long-term safety of such interventions [88,89,90]. On the other hand, patients with gastrointestinal-related abdominal pain, bloating, and constipation as well as suspicion of visceral hypersensibility may benefit from a gluten-free, low-Ni, or low-FODMAP diet. However, these diets may also be related to lower adherence due to the associated financial burden and inherent difficulties. Moreover, the safety of a long-term use of low-Ni has not been established while a long-term low-FODMAP diet can have negative effects on gut microbiota [91, 92]. The start of these diets should be decided in a multidisciplinary approach after gastrointestinal evaluation in order to exclude other pathological diagnoses.

Strengths and Limitations

A limitation of the review is that only studies reported in English were included, and there may be relevant studies in other languages, which were missed. The included studies varied significantly in the type of dietary intervention, the follow-up and the outcome measurements while they also suffered from a non-negligible risk of bias so that it was impossible to perform a meta-analysis and difficult to draw a clear picture. These limitations are partially due to the inherent weaknesses of dietary intervention studies in general. However, by presenting and discussing the results of the studies thoroughly, a clinical approach, according to the available level of evidence, can be now suggested which might consist a roadmap for clinicians and patients. Finally, the originality of the study should be mentioned since it represents the first systematic presentation of the up-to-date evidence on the therapeutic role of dietary interventions in endometriosis. The study is expected to enhance the clinical decision-making in the rapidly evolving field of patient’s active participation in the treatment against their disease.

Conclusions

Given that almost all studies in this review found a significant reduction of pain, dietary interventions appear promising to treat endometriosis-related symptoms. These results should however be treated with caution due to the limited number of available studies, the high heterogeneity and the high risk of bias. Proper counseling prior to the start of such treatments and where appropriate in a multidisciplinary setting including gastroenterologists and/or dieticians is warranted. Furthermore, well-designed randomized controlled trials are needed to accurately determine the short-term and long-term effectiveness and safety of dietary interventions.

References

Janssen EB, Rijkers AC, Hoppenbrouwers K, Meuleman C, D'Hooghe TM. Prevalence of endometriosis diagnosed by laparoscopy in adolescents with dysmenorrhea or chronic pelvic pain: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19(5):570–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmt016.

Gylfason JT, Kristjansson KA, Sverrisdottir G, Jonsdottir K, Rafnsson V, Geirsson RT. Pelvic endometriosis diagnosed in an entire nation over 20 years. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(3):237–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwq143.

Bougie O, Yap MI, Sikora L, Flaxman T, Singh S. Influence of race/ethnicity on prevalence and presentation of endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.15692.

Vercellini P, Fedele L, Aimi G, Pietropaolo G, Consonni D, Crosignani PG. Association between endometriosis stage, lesion type, patient characteristics and severity of pelvic pain symptoms: a multivariate analysis of over 1000 patients. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(1):266–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/del339.

Nirgianakis K, Gasparri ML, Radan AP, Villiger A, McKinnon B, Mosimann B, et al. Obstetric complications after laparoscopic excision of posterior deep infiltrating endometriosis: a case-control study. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(3):459–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.04.036.

Simoens S, Dunselman G, Dirksen C, Hummelshoj L, Bokor A, Brandes I, et al. The burden of endometriosis: costs and quality of life of women with endometriosis and treated in referral centres. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(5):1292–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/des073.

Practice bulletin no. 114: management of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(1):223–36. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e8b073.

Becker CM, Gattrell WT, Gude K, Singh SS. Reevaluating response and failure of medical treatment of endometriosis: a systematic review. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(1):125–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.05.004.

Lukas I, Kohl-Schwartz A, Geraedts K, Rauchfuss M, Wölfler MM, Häberlin F, et al. Satisfaction with medical support in women with endometriosis. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0208023. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208023.

Nirgianakis K, Vaineau C, Agliati L, McKinnon B, Gasparri ML, Mueller MD. Risk factors for non-response and discontinuation of Dienogest in endometriosis patients: a cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13969.

Marcoux S, Maheux R, Bérubé S. Laparoscopic surgery in infertile women with minimal or mild endometriosis. Canadian Collaborative Group on Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(4):217–22. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199707243370401.

Duffy JM, Arambage K, Correa FJ, Olive D, Farquhar C, Garry R, et al. Laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2014;(4):Cd011031. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011031.pub2.

Cea Soriano L, Lopez-Garcia E, Schulze-Rath R, Garcia Rodriguez LA. Incidence, treatment and recurrence of endometriosis in a UK-based population analysis using data from The Health Improvement Network and the Hospital Episode Statistics database. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2017;22(5):334–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/13625187.2017.1374362.

Guo SW. Recurrence of endometriosis and its control. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15(4):441–61. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmp007.

Vercellini P, Crosignani PG, Abbiati A, Somigliana E, Vigano P, Fedele L. The effect of surgery for symptomatic endometriosis: the other side of the story. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15(2):177–88. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmn062.

Nirgianakis K, Ma L, McKinnon B, Mueller MD. Recurrence patterns after surgery in patients with different endometriosis subtypes: a long-term hospital-based cohort study. J Clin Med. 2020;9(2):496.

Nirgianakis K, McKinnon B, Imboden S, Knabben L, Gloor B, Mueller MD. Laparoscopic management of bowel endometriosis: resection margins as a predictor of recurrence. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014;93(12):1262–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.12490.

Lee SR, Yi KW, Song JY, Seo SK, Lee DY, Cho S, et al. Efficacy and safety of long-term use of dienogest in women with ovarian endometrioma. Reprod Sci. 2018;25(3):341–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/1933719117725820.

Somigliana E, Vercellini P, Vigano P, Benaglia L, Busnelli A, Fedele L. Postoperative medical therapy after surgical treatment of endometriosis: from adjuvant therapy to tertiary prevention. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(3):328–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2013.10.007.

Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Martin-Calvo N. Mediterranean diet and life expectancy; beyond olive oil, fruits, and vegetables. Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care. 2016;19(6):401–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/mco.0000000000000316.

Panagiotakos DB, Georgousopoulou EN, Pitsavos C, Chrysohoou C, Metaxa V, Georgiopoulos GA, et al. Ten-year (2002-2012) cardiovascular disease incidence and all-cause mortality, in urban Greek population: the ATTICA study. Int J Cardiol. 2015;180:178–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.11.206.

Toledo E, Salas-Salvado J, Donat-Vargas C, Buil-Cosiales P, Estruch R, Ros E, et al. Mediterranean diet and invasive breast cancer risk among women at high cardiovascular risk in the PREDIMED trial: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(11):1752–60. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4838.

Valls-Pedret C, Sala-Vila A, Serra-Mir M, Corella D, de la Torre R, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, et al. Mediterranean diet and age-related cognitive decline: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1094–103. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1668.

Grodstein F, Goldman MB, Ryan L, Cramer DW. Relation of female infertility to consumption of caffeinated beverages. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137(12):1353–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116644.

Bérubé S, Marcoux S, Maheux R. Characteristics related to the prevalence of minimal or mild endometriosis in infertile women. Epidemiology. 1998;9(5):504–10. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001648-199809000-00006.

Matalliotakis IM, Cakmak H, Fragouli YG, Goumenou AG, Mahutte NG, Arici A. Epidemiological characteristics in women with and without endometriosis in the Yale series. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;277(5):389–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-007-0479-1.

Missmer SA, Chavarro JE, Malspeis S, Bertone-Johnson ER, Hornstein MD, Spiegelman D, et al. A prospective study of dietary fat consumption and endometriosis risk. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(6):1528–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deq044.

Trabert B, Peters U, De Roos AJ, Scholes D, Holt VL. Diet and risk of endometriosis in a population-based case-control study. Br J Nutr. 2011;105(3):459–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114510003661.

Heilier JF, Donnez J, Nackers F, Rousseau R, Verougstraete V, Rosenkranz K, et al. Environmental and host-associated risk factors in endometriosis and deep endometriotic nodules: a matched case-control study. Environ Res. 2007;103(1):121–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2006.04.004.

Tsuchiya M, Miura T, Hanaoka T, Iwasaki M, Sasaki H, Tanaka T, et al. Effect of soy isoflavones on endometriosis: interaction with estrogen receptor 2 gene polymorphism. Epidemiology. 2007;18(3):402–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ede.0000257571.01358.f9.

Savaris AL, Do Amaral VF. Nutrient intake, anthropometric data and correlations with the systemic antioxidant capacity of women with pelvic endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;158(2):314–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.05.014.

Harris HR, Eke AC, Chavarro JE, Missmer SA. Fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2018;33(4):715–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dey014.

Yamamoto A, Harris HR, Vitonis AF, Chavarro JE, Missmer SA. A prospective cohort study of meat and fish consumption and endometriosis risk. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(2):178.e1–e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2018.05.034.

Nodler JL, Harris HR, Chavarro JE, Frazier AL, Missmer SA. Dairy consumption during adolescence and endometriosis risk. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222(3):257.e1–e16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.09.010.

Youseflu S, Sadatmahalleh SJ, Mottaghi A, Kazemnejad A. Dietary phytoestrogen intake and the risk of endometriosis in iranian women: a case-control study. International Journal of Fertility and Sterility. 2020;13(4):296–300. https://doi.org/10.22074/ijfs.2020.5806.

Youseflu S, Jahanian Sadatmahalleh S, Mottaghi A, Kazemnejad A. The association of food consumption and nutrient intake with endometriosis risk in iranian women: a case-control study. International Journal of Reproductive BioMedicine. 2019;17(9):661–70. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijrm.v17i9.5102.

Schink M, Konturek PC, Herbert SL, Renner SP, Burghaus S, Blum S, et al. Different nutrient intake and prevalence of gastrointestinal comorbidities in women with endometriosis. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2019;70(2). https://doi.org/10.26402/jpp.2019.2.09.

Parazzini F, Chiaffarino F, Surace M, Chatenoud L, Cipriani S, Chiantera V, et al. Selected food intake and risk of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2004;19(8):1755–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deh395.

Parazzini F, Viganò P, Candiani M, Fedele L. Diet and endometriosis risk: a literature review. Reprod BioMed Online. 2013;26(4):323–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.12.011.

Saguyod SJU, Kelley AS, Velarde MC, Simmen RC. Diet and endometriosis-revisiting the linkages to inflammation. Journal of Endometriosis and Pelvic Pain Disorders. 2018;10(2):51–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/2284026518769022.

Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928.

Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: John Wiley & Sons; 2019.

Almassinokiani F, Khodaverdi S, Solaymani-Dodaran M, Akbari P, Pazouki A. Effects of vitamin D on endometriosis-related pain: a double-blind clinical trial. Med Sci Monit. 2016;22:4960–6. https://doi.org/10.12659/msm.901838.

Sesti F, Pietropolli A, Capozzolo T, Broccoli P, Pierangeli S, Bollea MR, et al. Hormonal suppression treatment or dietary therapy versus placebo in the control of painful symptoms after conservative surgery for endometriosis stage III-IV. A randomized comparative trial. Fertil Steril. 2007;88(6):1541–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.01.053.

Signorile PG, Viceconte R, Baldi A. Novel dietary supplement association reduces symptoms in endometriosis patients. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(8):5920–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.26401.

Mier-Cabrera J, Aburto-Soto T, Burrola-Mendez S, Jimenez-Zamudio L, Tolentino MC, Casanueva E, et al. Women with endometriosis improved their peripheral antioxidant markers after the application of a high antioxidant diet. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2009;7:54. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7827-7-54.

Borghini R, Porpora MG, Casale R, Marino M, Palmieri E, Greco N, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome-like disorders in endometriosis: prevalence of nickel sensitivity and effects of a low-nickel diet. An open-label pilot study. Nutrients. 2020;12(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12020341.

Ott J, Nouri K, Hrebacka D, Gutschelhofer S, Huber J, Wenzl R. Endometriosis and nutrition-recommending a Mediterranean diet decreases endometriosis-associated pain: an experimental observational study. J Aging Res Clin Practice. 2012;1:162–6.

Moore JS, Gibson PR, Perry RE, Burgell RE. Endometriosis in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: specific symptomatic and demographic profile, and response to the low FODMAP diet. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;57(2):201–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.12594.

Marziali M, Venza M, Lazzaro S, Lazzaro A, Micossi C, Stolfi VM. Gluten-free diet: a new strategy for management of painful endometriosis related symptoms? Minerva Chir. 2012;67(6):499–504.

Vennberg Karlsson J, Patel H, Premberg A. Experiences of health after dietary changes in endometriosis: a qualitative interview study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(2):e032321. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032321.

Marziali M, Capozzolo T. Role of gluten-free diet in the management of chronic pelvic pain of deep infiltranting endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22(6s):S51–s2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2015.08.142.

Rudzitis-Auth J, Körbel C, Scheuer C, Menger MD, Laschke MW. Xanthohumol inhibits growth and vascularization of developing endometriotic lesions. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(6):1735–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/des095.

Netsu S, Konno R, Odagiri K, Soma M, Fujiwara H, Suzuki M. Oral eicosapentaenoic acid supplementation as possible therapy for endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(4 Suppl):1496–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.08.014.

Park S, Lim W, Bazer FW, Whang KY, Song G. Quercetin inhibits proliferation of endometriosis regulating cyclin D1 and its target microRNAs in vitro and in vivo. J Nutr Biochem. 2019;63:87–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnutbio.2018.09.024.

Attaman JA, Stanic AK, Kim M, Lynch MP, Rueda BR, Styer AK. The anti-inflammatory impact of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids during the establishment of endometriosis-like lesions. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014;72(4):392–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/aji.12276.

Mariani M, Viganò P, Gentilini D, Camisa B, Caporizzo E, Di Lucia P, et al. The selective vitamin D receptor agonist, elocalcitol, reduces endometriosis development in a mouse model by inhibiting peritoneal inflammation. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(7):2010–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/des150.

Akyol A, Şimşek M, İlhan R, Can B, Baspinar M, Akyol H, et al. Efficacies of vitamin D and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on experimental endometriosis. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;55(6):835–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjog.2015.06.018.

Herington JL, Glore DR, Lucas JA, Osteen KG, Bruner-Tran KL. Dietary fish oil supplementation inhibits formation of endometriosis-associated adhesions in a chimeric mouse model. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(2):543–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.10.007.

Bruner-Tran KL, Osteen KG, Taylor HS, Sokalska A, Haines K, Duleba AJ. Resveratrol inhibits development of experimental endometriosis in vivo and reduces endometrial stromal cell invasiveness in vitro. Biol Reprod. 2011;84(1):106–12. https://doi.org/10.1095/biolreprod.110.086744.

Agostinis C, Zorzet S, De Leo R, Zauli G, De Seta F, Bulla R. The combination of N-acetyl cysteine, alpha-lipoic acid, and bromelain shows high anti-inflammatory properties in novel in vivo and in vitro models of endometriosis. Mediat Inflamm. 2015;2015:918089. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/918089.

Xu H, Lui WT, Chu CY, Ng PS, Wang CC, Rogers MS. Anti-angiogenic effects of green tea catechin on an experimental endometriosis mouse model. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(3):608–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/den417.

Yin B, Liu X, Guo SW. Caloric restriction dramatically stalls lesion growth in mice with induced endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2018;25(7):1024–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1933719118756755.

Heard ME, Melnyk SB, Simmen FA, Yang Y, Pabona JM, Simmen RC. High-fat diet promotion of endometriosis in an Immunocompetent mouse model is associated with altered peripheral and ectopic lesion redox and inflammatory status. Endocrinology. 2016;157(7):2870–82. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2016-1092.

Armour M, Sinclair J, Chalmers KJ, Smith CA. Self-management strategies amongst Australian women with endometriosis: a national online survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2019;19(1):17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-019-2431-x.

Fisher C, Adams J, Hickman L, Sibbritt D. The use of complementary and alternative medicine by 7427 Australian women with cyclic perimenstrual pain and discomfort: a cross-sectional study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16:129. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-016-1119-8.

Schwartz ASK, Gross E, Geraedts K, Rauchfuss M, Wolfler MM, Haberlin F, et al. The use of home remedies and complementary health approaches in endometriosis. Reprod BioMed Online. 2019;38(2):260–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2018.10.009.

Agarwal SK, Foster WG, Groessl EJ. Rethinking endometriosis care: applying the chronic care model via a multidisciplinary program for the care of women with endometriosis. Int J Women's Health. 2019;11:405–10. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S207373.

Kalaitzopoulos DR, Lempesis IG, Athanasaki F, Schizas D, Samartzis EP, Kolibianakis EM, et al. Association between vitamin D and endometriosis: a systematic review. Hormones (Athens). 2019;19:109–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42000-019-00166-w.

Lasco A, Catalano A, Benvenga S. Improvement of primary dysmenorrhea caused by a single oral dose of vitamin D: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(4):366–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2011.715.

Wu Z, Malihi Z, Stewart AW, Lawes CM, Scragg R. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain physician. 2016;19(7):415–27.

Supplementation in adolescent girls with endometriosis. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT02387931. Accessed 14 June 2020.

Santanam N, Kavtaradze N, Dominguez C, Rock JA, Parthasarathy S, Murphy AA. Antioxidant supplementation reduces total chemokines and inflammatory cytokines in women with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:32–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0015-0282(03)01887-9.

Flexofytol® for the treatment of endometriosis- associated pain. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04150406. Accessed 14 June 2020.

Evaluation of a nutraceutical for endometriosis pain relief. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04091191. Accessed 14 June 2020.

Curcumin supplementation for gynecological diseases. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03016039. Accessed 14 June 2020.

Efficacy of Trace Elements in the Treatment of Endometriosis: a pilot study. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT02437175. Accessed 14 June 2020.

Fomin VP, Gibbs SG, Vanam R, Morimiya A, Hurd WW. Effect of magnesium sulfate on contractile force and intracellular calcium concentration in pregnant human myometrium. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(5):1384–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2005.11.045.

Effect of Mediterranean diet and physical activity in patients with endometriosis. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03994432. Accessed 14 June 2020.

An AHEI Dietary intervention to reduce pain in women with endometriosis. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04259788. Accessed 14 June 2020.

Barrett JS. Extending our knowledge of fermentable, short-chain carbohydrates for managing gastrointestinal symptoms. Nutr Clin Pract. 2013;28(3):300–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/0884533613485790.

Issa B, Onon TS, Agrawal A, Shekhar C, Morris J, Hamdy S, et al. Visceral hypersensitivity in endometriosis: a new target for treatment? Gut. 2012;61(3):367–72. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300306.

Ek M, Roth B, Ekström P, Valentin L, Bengtsson M, Ohlsson B. Gastrointestinal symptoms among endometriosis patients—a case-cohort study. BMC Womens Health. 2015;15(1):59. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-015-0213-2.

Jess T, Frisch M, Jørgensen KT, Pedersen BV, Nielsen NM. Increased risk of inflammatory bowel disease in women with endometriosis: a nationwide Danish cohort study. Gut. 2012;61(9):1279–83. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301095.

Dietary treatment of endometriosis-related irritable bowel syndrome. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT02924493. Accessed 14 June 2020.

Pattanittum P, Kunyanone N, Brown J, Sangkomkamhang US, Barnes J, Seyfoddin V, et al. Dietary supplements for dysmenorrhoea. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2016;3:Cd002124. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002124.pub2.

Schwertner A, Conceicao Dos Santos CC, Costa GD, Deitos A, de Souza A, de Souza IC, et al. Efficacy of melatonin in the treatment of endometriosis: a phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pain. 2013;154(6):874–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2013.02.025.

Navarro VJ, Barnhart H, Bonkovsky HL, Davern T, Fontana RJ, Grant L, et al. Liver injury from herbals and dietary supplements in the U.S. Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md). 2014;60(4):1399–408. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.27317.

de Boer YS, Sherker AH. Herbal and dietary supplement-induced liver injury. Clinics in liver disease. 2017;21(1):135–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cld.2016.08.010.

Gardiner P, Phillips R, Shaughnessy AF. Herbal and dietary supplement--drug interactions in patients with chronic illnesses. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(1):73–8.

Heiman ML, Greenway FL. A healthy gastrointestinal microbiome is dependent on dietary diversity. Molecular metabolism. 2016;5(5):317–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2016.02.005.

Tuck CJ, Muir JG, Barrett JS, Gibson PR. Fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols: role in irritable bowel syndrome. Expert review of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2014;8(7):819–34. https://doi.org/10.1586/17474124.2014.917956.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Bern.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KN: concept and design, data analysis, interpretation, manuscript draft, manuscript revise, final approval. KE: literature search, data analysis, interpretation, manuscript draft, final approval. DRK: literature search, data analysis, interpretation, manuscript revise, final approval. SL: data interpretation, manuscript revise, final approval. LB: data interpretation, manuscript revise, final approval. MDM: data interpretation, manuscript revise, final approval.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

In adherence to the Conflict of Interest policy recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) all authors state explicitly that potential conflicts of interest do not exist for this research work.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Konstantinos Nirgianakis, MD and Katharina Egger are joint First Authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nirgianakis, K., Egger, K., Kalaitzopoulos, D.R. et al. Effectiveness of Dietary Interventions in the Treatment of Endometriosis: a Systematic Review. Reprod. Sci. 29, 26–42 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43032-020-00418-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43032-020-00418-w