Abstract

The Himalayan Mountains and valley glaciers within it are coupled in such a way that they maintain the ecosystem along the draining stream from the young to old stage. They produce meltwater and nutrient-rich sediments, which serve as precious resources for low-lying areas. Meltwater is assumed to be an important agent of transportation and deposition of sediments in warm-based valley glaciers. Overall, the glacial environment acts as a good erosional system, and the sediments produced form a good-quality aquifer above the hard bedrock in the outwash plain. The glaciofluvial and glaciolacustrine sediments were collected from the Chandra Basin and analysed for the permeability, porosity, density and statistical parameters. Correlation among the different parameters was explained through the regression analysis. The correlation between permeability and mean grain size showed a good regression coefficient, R2 = 0.86 and R2 = 0.97, for glaciofluvial and glaciolacustrine sediments respectively. Correlation between density and porosity was also established against the mean grain size with a good regression coefficient. The physioempirical parameters, effective diameter (D10) and coefficient of uniformity (Cu) were also examined for their dependability on permeability. Hence, this preliminary study attempts to use sediment grain size and texture as a tool to understand the permeability, porosity, density and movement and mobility of water through the glaciofluvial and glaciolacustrine sediments. Also, the correlation study showed that the mean grain size could be used as a factor for predicting the physioempirical model in that region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The supraglacial, englacial and subglacial hydraulic systems together produce assorted sediments that are drained by glacial meltwater; these characteristic sediments are called glaciofluvial sediments [1]. Sometimes meltwater dammed by moraines or ice turns into a lake; the characteristic sediments in and around these lakes are called glaciolacustrine sediments [3]. These sediments represent the characteristics of the erosional environment and act as a reservoir for natural water storage.

Permeability, porosity and density are the three factors that greatly influence many geological processes [7]. Permeability, one of the important parameters, is measured to understand the storability, passage of water from different sources (rain, snow, ice and groundwater) and channel loss through the sediments in the flow direction [38]. Since permeability is the measure of the ease with which water moves through aquifer material, certain relationships must exist between permeability and the statistical parameters that describe the grain size distribution of the porous medium [22].

Although many methods have been developed by geologists, soil scientists and engineers to estimate the permeability of sediment and rock, there is still lack of adequate understanding [31]. Summers and Weber [37] mentioned that insufficient data exist for measuring the permeability especially in the glacial environment where poorly sorted sediments are common. There are several other methods for estimating the permeability of sediments. One of the better but expensive and time-consuming methods is the field pumping or injection test. Another method is the permeameter method, in which fluid is allowed to flow through the sample in the laboratory. The third method includes analysis of grain size data from mechanical sieving and then predicting the permeability using the empirical formulas [31].

Permeability is a function of porosity, grain size and sorting. When combined, the pores of the sediments act as a water conduit to transmit water through them and hence serve as an important parameter in groundwater characterization. In general, the total porosity of the unconsolidated material varies from 0.25 to 0.7 (25–70%) [24]. The bulk density depends upon the water content of the sediment and is highly variable as the water content in sediment changes because of compaction [18]. Permeability generally increases with an increase in the void ratio and decreases with an increase in density.

So far, many works have been carried out to relate the permeability with the grain statistics by using empirical formulas. Hazen [17] and Slichter [34] explained the dependability of permeability on grain size. They deduced the formula that relates the permeability proportional to the square of the grain diameter (k = cd2). This basic formula has been experimentally verified and modified by many others [5, 19, 30]. Masch and Denny [22] explained the dependability of permeability of the unconsolidated sands on various statistical parameters such as the median, standard deviation, skewness and kurtosis. For unconsolidated sediments, the dependability of permeability on various grain size data was also explained by the many investigators [16, 25, 28].

Advancements in science have led to the characterization of sediments through enhanced geophysical methods [4, 10,11,12, 14, 23, 32, 33], but still the predictability of hydrogeological parameters follows the same trend [21, 36, 39]. Many studies have been carried out in the Himalayan catchment, emphasizing the suspended sediment load [26, 27], but there is a missing link between sediment properties and their characteristics in the glaciofluvial and glaciolacustrine environment. Direct methods of permeability estimation are difficult to conduct on the undulating surfaces of the Himalayas; hence, an indirect method may be more feasible and workable. The hydrological properties of sediment estimation will serve as a key factor in calculating the channel loss to aquifer and groundwater recharge. Here, an attempt has been made to prepare the baseline for future research work, which could be vital to understand the movement, mobility and channel loss of water in a glaciated valley. The study includes laboratory analysis of samples taken from the glaciated region and their physical property determination using grain size analysis. We also attempt to determine the interrelationship among the different physical and empirical quantities.

2 Study area

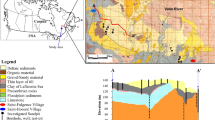

Surficial grab sediments were collected from near the base camp and snout of the Chhota Shigri glacier and around the periphery of Chandratal Lake (Fig. 1). Among the samples that signify glaciofluvial characteristics, collected from the Chhota Shigri glacier stream, three represent discharge sites (~ 2.0 km) down the snout and another was collected near the snout of the glacier (Fig. 2a). To demonstrate glaciolacustrine features, four samples were collected around the periphery of Chandratal Lake, which lies ~ 30 km away from Chhota Shigri glacier in Chandra Basin, Himachal Pradesh (Fig. 2b).

Being in the Central Crystalline Belt of the Pir Panjal range in the Indian Himalaya, the Chandra Basin mainly shows metamorphosed features. The dominant composition of this central crystalline axis shows a range from meso- to ketazonal metamorphites, migmatites and gneisses [20]. Additionally, we could see granitic rocks of varying compositions in a few places. These rock intrusions are younger and show rejuvenation. Around 3 km upstream of Chhota Dara (Chandra Basin), in the upper Chandra Valley, older granitic rocks from the Paleozoic Age were seen. The fauna-rich sediment formation (Haimanta system) of the Spiti region was seen as an overlying formation demarcated with a tectonic break; the dominant rocks of the Haimanta system include black slates, phyllites and fine-grained biotite-schists [8, 20]. The slates and phyllites are well exposed in the form of thrust tectonic contact and lie at the crest of the northern ridge. Box-type folds with decollement are quite prominent along the Haimanta Formation in Chandra Basin.

3 Methodology

The glaciofluvial and glaciolacustrine sediments were analysed for statistical and physical parameters, i.e., the mean, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis, porosity, permeability and bulk density. All samples were air dried for 3–4 days in the laboratory. The samples were passed through a 2-mm sieve to remove sediments > 2 mm and kept in airtight polybags. Particles > 2 mm were sieved out because particles of this size do not influence the hydrogeological processes, especially the groundwater storage, mobility and movement [6, 9]. All samples were processed in the laboratory mainly for three parameters: grain size analysis, porosity and bulk density. Grain size distribution was analysed using mechanical sieving. In the grain size analysis, sieves of 1 mm, 0.5 mm, 0.25 mm, 0.125 mm, 0.063 mm, 0.037 mm and 0.030 mm were used. The graphical statistics method was used to calculate the statistical parameters [15]. The sediments were sieved up to the 95% passing diameter. The weight of the sample on the individual sieve was measured electronically. The cumulative curves were plotted for the sieved data (Fig. 3). Phi values of 5%, 16%, 25%, 50%, 75%, 84% and 95% passing diameter were calculated from the cumulative curves (Table 1) and applied to the statistical formulas given by Folk and Ward [15]. Hence, the mean diameter, standard deviation, skewness and kurtosis of each sample were calculated. Statistical calculations were performed using the graphic method and the following empirical equations were considered.

-

(1)

Mean (Mz): the average grain size in the sample is defined as the mean value of the sample. It is an arithmetic mean of all the distributed grain sizes in the sample,

$$M_{z} = \frac{{\phi_{16} + \phi_{50} + \phi_{84} }}{3}$$ -

(2)

Inclusive graphic (σi) standard deviation: this is a statistical explanation for sorting the grains. It is a measurement of the range of the grain size distribution in the sample,

$$\sigma_{i} = \frac{{\phi_{84} - \phi_{16} }}{4} + \frac{{\phi_{95} - \phi_{5} }}{6.6}$$ -

(3)

Inclusive graphic skewness (SKt): skewness is defined as the degree of asymmetry from the normal or log-normal grain size distribution. Skewness can be positive or negative depending upon the excess tail of fine or coarse particles, respectively,

$$SK_{t} = \frac{{\phi_{16} + \phi_{84} - 2\phi_{50} }}{{2\left( {\phi_{16} - \phi_{84} } \right)}} + \frac{{\phi_{95} + \phi_{5} - 2\phi_{50} }}{{2\left( {\phi_{95} - \phi_{5} } \right)}}$$ -

(4)

Graphic kurtosis (KG): the degree of sharpness or peakedness of the grain size distribution curve is known as the kurtosis,

$$K_{G} = \frac{{\left( {\phi_{95} - \phi_{5} } \right)}}{{2.44\left( {\phi_{75} - \phi_{25} } \right)}}$$

Permeability was empirically calculated by applying the sieved data to the [19] equation. The equation uses the grain size data to predict the permeability of sediments,

where \(k\) is the permeability of the sediment, \(d\) is the mean grain size in mm, and \(\sigma_{i}\) is the standard deviation in phi (ϕ). Phi (ϕ) and mm are related by the formula,

The porosity was calculated through the column saturation method. In the saturation method, water was allowed to flow against gravity in a column filled with the sample. The volume of water required to saturate the sample was measured and divided by the total volume to obtain the porosity of each sample. The density was calculated by the volumetric method. The sample was poured into the known volume of a vial and pressed to duplicate the natural compaction of material. The volume and weight of each sample were determined to obtain the density of the individual sample.

4 Results

4.1 Statistical analysis

4.1.1 Glaciofluvial sediments

Among four samples, the first two were fine sands and the other two very fine sands. The reason for the presence of very fine sand could be the location of the sample site close to the snout as rock flour is produced by the glacier in the snout region because of abrasion between the glacier ice and bedrock. As expected in the glacial environment, the sediments were poorly sorted except for the first sample, which was moderately sorted. The first sample was collected from the left bank of the glacial stream, looking toward the glacier. The rapid flow did not affect the samples on the left bank; hence, they were exposed to the weathering phenomenon for a long time and moved from poorly to moderately sorted. The first two samples were symmetrically skewed but the other two were negatively skewed because of the presence of a higher percentage of coarse particles. The kurtosis varied from mesokurtic to leptokurtic. The porosity of the samples was found to vary from 23.556 to 32.88% (Table 2). The two samples showed greater porosity. This can be explained by two reasons: they were more sorted than the other samples and had the a higher percentage of finer particles. Permeability is highly correlated with the sorting of the samples. As the sorting decreased, the permeability also decreased. However, the permeability showed a negative correlation with the porosity and density, i.e. permeability decreased with an increase in porosity and increased with an increase in density. The negative correlation of the permeability could be because of the grain texture, i.e. grain shape (angularity, roundness, sphericity) and sorting.

4.1.2 Glaciolacustrine sediments

Among four samples, two were coarse sand and two medium sand. This variation must be because of the change in drainage morphology around the lake. In general, around the periphery of the lake, we get more assorted and coarse sediments, and as we move towards the base of the lake the assorting and grain sizes both decrease. So, as expected, poorly sorted sediments were found in glaciolacustrine environments. Samples varied from the near symmetrical to negatively skewed, i.e. the percentage of finer sediments was more than that of the coarse sediments. The kurtosis was found to vary from platykurtic to leptokurtic, which means medium size to fine size sediments were more sorted in this environment. In the lake samples, the porosity was lower than in the glaciofluvial environment; hence, the samples showed greater permeability. Their porosity varied from 22.74 to 24.812%, while permeability varied from 1.042 to 9.389 Darcy (Table 3). The density of the sediments was comparable in both environments. The size range of all statistical parameters is shown (Fig. 4).

4.2 Dependability of porosity, permeability and density on grain texture

Permeability is highly correlated with the mean/median grain size [31]. The glaciofluvial sediments showed a good correlation of permeability against mean grain size with a regression coefficient of 0.8586. The glaciolacustrine sediments showed even higher correlation than the glaciofluvial sediments with a regression coefficient of 0.9752 (Table 4). The good correlation between the permeability and mean grain size in both the environments of Chandra Basin proved the strong dependability of the permeability on mean grain size. Other parameters such as standard deviation, skewness and kurtosis did not show any significant correlation between the two environments. Standard deviation and skewness were individually correlated with the glaciofluvial sediments, and kurtosis was individually correlated among the glaciolacustrine sediments. Hence, the mean grain size can be a preferred parameter over the other textures for the study of permeability in this particular environment (Fig. 5).

For the unsorted sediments, the mean grain size was correlated with the fractional porosity of the sediments [29]. Generally, porosity increases with decreasing mean grain size. The glaciofluvial sediments showed a good correlation (R2 = 0.8289) between porosity and mean grain size (Table 4). Similarly, the glaciolacustrine sediments also showed a positive correlation (R2 = 0.581). The opposite correlation of porosity with mean grain size in the glaciolacustrine environment indicates some disturbance in the environment; the grain shape factor (angularity, roundness, sphericity) could be the reason for this. Mean grain size could also be a modelling factor for determining the porosity in the glaciofluvial environment. However, porosity did not show a good relation with the sorting (standard deviation) in these samples.

Density is a function of particle size distribution [35]. The result analysed for the different glaciofluvial sediments showed that bulk density of the sediment increased with an increase in mean grain size. The mean grain size of glaciofluvial sediments showed a good correlation with density with a regression coefficient of 0.8692 but the glaciolacustrine sediments did not show any correlation (Table 4). The standard deviation (sorting) against porosity was only correlated in the glaciolacustrine sediments (R2 = 0.6110) but not in the glaciofluvial sediments.

4.3 Dependability of permeability on physioempirical parameters

The effective diameter (D10) and coefficient of uniformity (Cu) of soil are generally used for the prediction of the physioempirical model [2]. The D10and Cu are highly correlated with the permeability [13]. The D10 is generally used to speculate various properties of the whole mass. D10 is generally related to most of the soil properties; hence, this was used to empirically calculate most of the physical parameters of soil. The glaciofluvial sediments did not show good correlation of permeability with D10 viz. the regression coefficient was found to be 0.0631 whereas glaciolacustrine sediments showed a good relationship with the regression coefficient of 0.6723 (Fig. 6). The Cu showed a quite good relationship with the permeability of the sediments, but for the glaciolacustrine sediments, it was negatively correlated compared with the glaciofluvial sediments. This too represents some instability in the glaciolacustrine environment. Therefore, D10 and Cu cannot be used to empirically determine different physical aspects of the sediments in these regions.

5 Conclusion

In the glacial environment, it is difficult to model the sediment characteristics because of their highly assorted nature. As glaciers are very vulnerable to climate change, depending upon the place, the nature of erosion and sediment production varies. Therefore, it is difficult to predict a spatial model for the glacial environment. The study in the Chandra Basin was a preliminary approach to determine the parameters best correlated with permeability, porosity and density in two selected regions. The article explained the importance of sediment characteristics in a glacier terrain. The rigorous explanation of recharge and discharge in a proglacial environment can only be concluded by measuring parameters such as permeability, porosity, density and so on. The study included two important proglacial environments, i.e. glaciofluvial and glaciolacustrine. The main characteristic of the glacial environment is an extremely heterogeneous assortment of particles ranging from clay-size grains to meter-size boulders. Due to the extremely heterogeneous nature of sediment in the glacial environment, the grain texture plays an important role in controlling the permeability of sediments. The study showed the role of sediment size in controlling the permeability, porosity and density. The study also attempted to determine the relationship of permeability, porosity and density with grain texture. These parameters greatly affect the baseflow of the glacial stream, which acts as a fundamental factor in the glacio-hydrological system. The permeability of the glaciofluvial and glaciolacustrine sediments showed a good correlation with the mean grain size. Porosity and density of the glaciofluvial sediments also showed a good correlation with the mean grain size. Hence, mean grain size could be a determining factor for the physioempirical model in these two selected regions especially for the glaciofluvial environment around the Chhota Shigri glacier. The data on glaciolacustrine sediments indicated some instability in the environment around Chandratal Lake. As the study included a limited area and limited samples, more detailed study should be undertaken to determine the hydrology of proglacial and subsurface movements.

References

Anderson MP (1989) Hydrogeologic facies models to delineate large-scale spatial trends in glacial and glaciofluvial sediments. Geol Soc Am Bull 101:501–511

Arya LM, Paris JF (1981) A physicoempirical model to predict the soil moisture characteristic from particle-size distribution and bulk density data 1. Soil Sci Soc Am J 45:1023–1030

Ashley GM (1988) Classification of glaciolacustrine sediments. Genetic classification of glacigenic deposits. A.A. Balkema, Rotterdam, pp 243–260

Auken E, Pellerin L, Christensen NB, Sørensen K (2006) A survey of current trends in near-surface electrical and electromagnetic methods. Geophysics 71:G249–G260

Bear J (1972) Dynamics of fluids in porous media. Elsevier, New York

Bittelli M, Campbell GS, Flury M (1999) Characterization of particle-size distribution in soils with a fragmentation model. Soil Sci Soc Am J 63:782–788

Boggs S Jr (2006) Sedimentology and stratigraphy. Pearson Education, London

Rawat BS, Purohit KK (1988) Geology of the area around Chhota Shigri Glacier, Lahaul Spiti District, Himachal Pradesh. Technical report. Department of Science and Technology, Government of India, New Delhi

Burt R (2014) Kellogg soil survey laboratory methods manual. United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, National Soil Survey Center, Kellogg Soil Survey Laboratory

Chatterjee R, Gupta SD, Farooqui MY (2012) Application of nuclear magnetic resonance logs for evaluating low-resistivity reservoirs: a case study from the Cambay basin, India. J Geophys Eng 9:595

Chatterjee R, Singha DK, Ojha M et al (2016) Porosity estimation from pre-stack seismic data in gas-hydrate bearing sediments, Krishna-Godavari basin, India. J Nat Gas Sci Eng 33:562–572

Das B, Chatterjee R (2018) Well log data analysis for lithology and fluid identification in Krishna-Godavari Basin, India. Arab J Geosci 11:231

Detmer DM (1995) Permeability, porosity, and grain-size distribution of selected Pliocene and Quaternary sediments in the Albuquerque Basin. N M Geol 17:79–87

Everett ME (2012) Theoretical developments in electromagnetic induction geophysics with selected applications in the near surface. Surv Geophys 33:29–63

Folk RL, Ward WC (1957) Brazos River bar: a study in the significance of grain size parameters. J Sediment Res 27:3–26

Graton LC, Fraser HJ (1935) Systematic packing of spheres: with particular relation to porosity and permeability. J Geol 43:785–909

Hazen A (1983) Some physical properties of sand and gravel with special reference to their use in filtration. In: 24th annual report on Massachusetts State Board of Health, Boston

Jepsen R, Roberts J, Lick W (1997) Effects of bulk density on sediment erosion rates. Water Air Soil Pollut 99:21–31

Krumbein WC, Monk GD (1943) Permeability as a function of the size parameters of unconsolidated sand. Trans AIME 151:153–163

Kumar S, Rai H, Purohit KK et al (1987) Multi disciplinary glacier expedition to Chhota Shigri glacier. Technical report. Department of Science and Technology, Government of India, New Delhi

Lu C, Chen X, Cheng C et al (2012) Horizontal hydraulic conductivity of shallow streambed sediments and comparison with the grain-size analysis results. Hydrol Process 26:454–466

Masch FD, Denny KJ (1966) Grain size distribution and its effect on the permeability of unconsolidated sands. Water Resour Res 2:665–677

Mondal S, Yadav A, Chatterjee R (2018) Integration of rock physical signatures with depositional environments: a case study from East Coast of India. J Appl Geophys 148:256–264

Morris DA, Johnson AI (1967) Summary of hydrologic and physical properties of rock and soil materials, as analyzed by the hydrologic laboratory of the US Geological Survey, 1948-60. U.S. Government Publishing Office, Washington

Morrow NR, Huppler JD, Simmons AB (1969) Porosity and permeability of unconsolidated, upper Miocene sands from grain-size analysis. J Sediment Res 39:312–321

Pandey SK, Singh AK, Hasnain SI (2002) Grain-size distribution, morphoscopy and elemental chemistry of suspended sediments of Pindari Glacier, Kumaon Himalaya, India. Hydrol Sci J 47:213–226

Panwar S, Khan MYA, Chakrapani GJ (2016) Grain size characteristics and provenance determination of sediment and dissolved load of Alaknanda River, Garhwal Himalaya, India. Environ Earth Sci 75:91

Pryor WA (1972) Reservoir inhomogeneities of some recent sand bodies. Soc Pet Eng J 12:229–245

Rogers JJ, Head WB (1961) Relationships between porosity, median size, and sorting coefficients of synthetic sands. J Sediment Res 31:467–470

Schriever W (1930) Law of flow for the passage of a gas-free liquid through a spherical-grain sand. Trans AIME 86:329–336

Shepherd RG (1989) Correlations of permeability and grain size. Groundwater 27:633–638

Singha D, Chatterjee R (2017) Rock physics modeling in sand reservoir through well log analysis, Krishna-Godavari basin, India. Geomech Eng 13:99–117

Slater L (2007) Near surface electrical characterization of hydraulic conductivity: from petrophysical properties to aquifer geometries—a review. Surv Geophys 28:169–197

Slichter CS (1899) Theoretical investigation of the motion of ground waters. In: 19th annual report on US Geophysical Survey, pp 304–319

Sohn HY, Moreland C (1968) The effect of particle size distribution on packing density. Can J Chem Eng 46:162–167

Song J, Chen X, Cheng C et al (2009) Feasibility of grain-size analysis methods for determination of vertical hydraulic conductivity of streambeds. J Hydrol 375:428–437

Summers WK, Weber PA (1984) The relationship of grain-size distribution and hydraulic conductivity—an alternate approach. Groundwater 22:474–475

Todd DK (1959) Ground water hydrology. Wiley, New York

Wang J-P, François B, Lambert P (2017) Equations for hydraulic conductivity estimation from particle size distribution: a dimensional analysis. Water Resour Res 53:8127–8134

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jawaharlal Nehru University for providing the necessary arrangements for the experiment under the institutional umbrella. Additionally, the authors also thank the School of Environmental Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, for support with funds for the field visit, sample collection and laboratory equipment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Mr. Aniket Gupta and Dr. A.L. Ramanathan declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gupta, A., Ramanathan, A.L. Grain texture as a proxy to understand porosity, permeability and density in Chandra Basin, India. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 1 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-018-0001-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-018-0001-3