Abstract

Recent years have witnessed an increasing scholarly interest in the study of education, training, and skill formation from a comparative political economy perspective. The purpose of this article is to contribute to the emerging field of the political economy of adult learning systems, which seeks to understand the causes and consequences of cross-national diversity in adult learning systems. The article introduces this interdisciplinary research strand by reviewing recent work and different typologies that have emerged out of the field of comparative economics and comparative politics, which are relevant to the study of adult learning systems. The empirical evidence on cross-national patterns of organized adult learning drawn on PIAAC data suggests that existing typologies are insufficient to explain the cross-national patterns. The article discusses some specific institutional features that promote adult learning participation and points out conditions and policies that support effective adult learning systems.

Zusammenfassung

In den vergangenen Jahren ist ein zunehmendes wissenschaftliches Interesse an der Untersuchung von Bildung, Ausbildung und Weiterbildung aus einer vergleichenden politisch-ökonomischen Perspektive zu verzeichnen. Der Artikel untersucht Ursachen und Folgen der länderspezifischen Vielfalt in Weiterbildungssystemen und leistet damit einen Beitrag zu dem neu entstehenden Forschungsbereich der politischen Ökonomie von Weiterbildungssystemen. Der Beitrag führt in diesen interdisziplinären Forschungsstrang ein, indem er einen Überblick über die jüngsten Arbeiten und verschiedene Typologien gibt, die aus dem Bereich der vergleichenden Ökonomie und der vergleichenden Politikwissenschaft hervorgegangen und die für die Untersuchung von Weiterbildungssystemen relevant sind. Die empirische Evidenz zu länderspezifischen Mustern des organisierten Erwachsenenlernens, die sich auf PIAAC-Daten stützt, legt nahe, dass die bestehenden Typologien nicht ausreichen, um die länderspezifischen Muster zu erklären. Der Artikel erörtert einige spezifische institutionelle Merkmale, die Weiterbildungsbeteiligung fördern, und zeigt Bedingungen und Politiken auf, die effektive Weiterbildungssysteme unterstützen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The term “political economy” is often associated with economic processes and socio-political conditions under which production is organized within nation states. The origins of the term can be traced back to the works of Adam Smith, David Ricardo and Karl Marx who are regarded as some of the most important forbearers of political economy. Today, it has been adopted in a variety of disciplines and fields when studying the linkages and interactions between politics and the formation, organisation, and functioning of economic and social institutions. Recent years have witnessed an increasing scholarly interest from political scientists, economists and sociologists to study education, training, lifelong learning and skills, leading to a proliferation of concepts such as the political economy of skills (Brown et al. 2001; Thelen 2004; Busemeyer and Trampusch 2012), the political economy of education reform (Busemeyer 2015), and the political economy of adult learning (Rees 2013; Desjardins 2017, 2018) among others. Education, training, adult learning and skills are central topics of the educational sciences including comparative education, but they have now become increasingly a focal point of interest for scholars of comparative politics and comparative economics. Typically, a common feature among these concepts is that they primarily deal with the political, economic and social institutions that affect the evolution of education and skill formation systems, policies and reforms as well as related distributional aspects and conflicts.

The purpose of this article is to introduce the emerging interdisciplinary field of the political economy of adult learning and highlight some institutional features that promote adult learning including insights and nuances relevant to furthering this field of research. First, we review some of the literature related to the political economy of Adult Learning Systems (ALS) and associated variants such as the political economy of skill formation and the political economy of education more generally. A full review of the relevant literature goes beyond the scope of this article, which is why we focus on typologies that have emerged out of the field of comparative politics and comparative economics that are applied more directly to the educational sciences, including comparative education, whereby education, training, adult learning and skills have been the focal points. Second, drawing on PIAAC and IALS data we provide empirical evidence on cross-national participation patterns in organized adult learning, which suggests that existing typologies of “institutional packages” are insufficient to explain the cross-national patterns. Finally, we discuss a range of more specific institutional features that are more proximally related to ALS and point out conditions that shape effective and inclusive ALS.

2 Multi-disciplinary scholarship contributing to the political economy of adult learning systems

2.1 Defining adult learning systems

In discussing the emerging field of the political economy of adult learning systems (ALS), we first define what we mean by the term “adult learning systems”. Our perspective is that ALS refer to the mass of organized learning opportunities (both formal and non-formal) available to adults along with their underlying structures and stakeholders that shape their organization and governance (Desjardins 2017). Organized adult learning is defined as any learning opportunities, formal and non-formal, undertaken by adults (both younger and older) who are not in their regular cycle of education and includes non-traditional students in formal education. Non-traditional students are defined as adults (both younger and older) who are not in their regular cycle of education but undertake organized learning opportunities including the completion (or pursuit) of a formal qualification in a manner, that does not follow a “traditional” or exclusively “front-loaded” path. The latter typically involves second chance adaptations to formal education that enable and support (older) adults, but in some cases, it might simply involve flexibility and the opening up of formal education structures to non-traditional students.

As defined, ALS interact with formal education structures in many countries and they are often regarded as part of the education system but extend well beyond involving a variety of institutions from labour market to civil society. Moreover, in terms of input, outcomes and returns, ALS are clearly interrelated with the economic and production system. For example, the skill orientation of an economy can influence the conditions for the acquisition, use and maintenance of skills; specific educational and labour market institutions (e.g. dual training) can facilitate or hamper the transition from school to working life.

From this perspective, ALS are embedded in characteristic regimes of economic and social institutions, which can be understood in terms of a systematic and emerging political economy of ALS (Rees 2013; Desjardins 2017, 2018). ALS contain provisions that are less regulated and less standardised than K‑12, higher education, or vocational education and training (VET), and are not mainly financed by the state (Ioannidou and Jenner 2020). ALS differ considerably across countries, more than the regular cycle of formal education does, where the latter tends to reflect “institutional isomorphism” (DiMaggio and Powell 1983, pp. 148–53; Meyer and Ramirez 2003)—a process of increasing homogeneity amongst different organisations according to sociological neo-institutionalism—around the world. In many countries, ALS have manifested themselves through various bottom-up processes, for example, on the initiative of labour and civil society movements. In others, public policy frameworks led by the state have played a substantial role in fostering the development of ALS by emphasizing the extension of basic education and second chances to adults, as well as opening up vocational and higher education to young and older adults who may not have followed an exclusively “front-loaded” path (i.e. non-traditional students). Yet in many other countries, ALS are lacking some of the institutional features necessary to even be considered a system per se.

ALS are in general not only less regulated but also less homogeneous than the regular cycle of formal education regarding their institutional structure, function and target groups. They include—according to the classification provided by Desjardins (2017, pp. 19–20)—Adult Basic (and General) Education (ABE/AGE), Adult Higher Education (AHE), Adult Vocational Education (AVE), and Adult Liberal Education (ALE). ABE/AGE typically involve formal education, which corresponds to the UNESCO International Standardized Education Classification (ISCED) 1, 2 or 3, but are undertaken by non-traditional students as defined above. AHE typically involve formal education undertaken by non-traditional students, which corresponds to ISCED 5 or 6. AVE can involve formal education undertaken by non-traditional students—corresponding to ISCED 3b, 3c, 4, or 5b—but also non-formal education that has no links to the formal qualification system (e.g. on-the-job training or workshops and seminars that are job-related). Adult Liberal Education (ALE) is mostly non-formal and associated with the civil society sector. Yet, in highly flexible systems such as in Denmark, even some ALE courses may be linked to formal recognized qualifications via a modular and flexible approach.

2.2 Multi-disciplinary scholarship stimulating adult education research from a political economy perspective

This section reviews multi-disciplinary scholarship that has stimulated adult education research and provides a brief overview of different typologies that have emerged out of the field of comparative economics and comparative politics, which are relevant to, and have directly contributed to, the study of the political economy of adult learning systems.

The seminal work of Hall and Soskice (2001) in comparative economics on the Varieties of Capitalism (VoC) brought education and training to the forefront for many social scientists including economists, sociologists and political scientists. This work was preceded by the influential work of Esping-Andersen in comparative politics about the Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism (1990) and their implications for social policy including education.

Esping-Andersen provided a broad way of classifying welfare conditions by examining the relationship between market and state, in particular the extent of social benefits along the two dimensions of de-commodification and stratification. De-commodification described the relative independence of the individual from the labour market (Esping-Andersen 1998, pp. 21–22). A high degree of de-commodification indicates a welfare state with extensive access to social services and benefits. The other dimension, stratification, shows the extent to which a welfare state does not only degrade inequalities, but also creates them by preserving social differences or privileges for certain groups. It is claimed that the welfare state—apart from its purely income-distributive role—shapes class and status in a variety of ways: “The education system is an obvious and much-studied instance, in which individuals’ mobility chances not only are affected, but from which entire class structures evolve” (Ibid., pp. 57–58).

Esping-Andersen differentiates between three “ideal” types of welfare state regimes: the liberal, the conservative and the social democratic welfare state. The liberal welfare state emphasizes the free market and shows a low degree of de-commodification (the dependency of the individuals is hardly restricted by de-commodified services) and a low institutional stratification (e.g. United States, Canada, and Australia). In contrast to this, the conservative welfare state (e.g. Austria, France, and Germany) demonstrates corporatist structures, maintaining of status differences accompanied by a high degree of stratification, moderate degree of de-commodification and a clear dependency of access to government benefits from the position on the labour market. The social-democratic welfare state (Scandinavian countries) is characterized by guaranteeing universal services based on citizenship and therefore a high degree of de-commodification and a low degree of stratification, which both lead to a reduced social inequality (see Esping-Andersen 1998, pp. 27–28).

Esping-Andersen’s typology has been by far the most influential classification in comparative welfare state research and has successfully oriented scholarship in various research fields, also with regard to education (Allmendinger and Leibfried 2003; Willemse and de Beer 2012). Although the typology and its various extensions to other regime types (e.g. Southern European, see Ferrara 1996) is still widely used in comparative political research, it has been extensively challenged both on empirical and analytical grounds (Powell 2015; Rice 2013; Arts and Gelissen 2002; Ferragina and Seeleib-Kaiser 2011). Besides the fact that many empirical welfare states seem to be hybrid cases of the established welfare regime categories, the typology dates back to the 1990s with data designed around the 1980s. A re-assessment of its robustness as well as the inclusion of new dimensions seem necessary (Danforth 2014), taking also into account that in the meantime many countries have undergone major transformations. More important, a meta-review that claims that 23 studies confirm Esping-Andersen’s typology exclude all studies that consider health care and education as part of the welfare state because these two social policy areas follow ‘a distinct, different logic from de-commodification [and] social stratification’ (Ferragina and Seeleib-Kaiser 2011, p. 587).

A major alternative to Esping-Andersen’s welfare state classification is the Varieties of Capitalism approach by Hall and Soskice (2001). Hall and Soskice identified education and training as one of the five institutional spheres of political economies (2001, pp. 25–26) and they explicitly connect skill formation systems with types of market economies by linking distinct systems of skill formation to varieties of capitalism. They point to nation-specific institutions such as labour market institutions, production regimes and welfare state that play a crucial role and shape “institutional complementarities” in the sense that ‘the presence (or efficiency) of one institution increases the returns from the other’ (Ibid, p. 17). At the highest level of their typology, they distinguish between liberal market economies (LME) and coordinated market economies (CME) (Ibid.). A crucial element in their typology is that the specificity of skills among the population differ by regimes. Whereas LME such as the case of the USA generate primarily generic skills through general and higher education, which can be complemented by on the job training over the lifespan, CME such as in the case of Germany emphasize specific skills through a well-developed VET system including apprenticeship schemes. Whether LME or rather CME are more conducive to adult education and training is subjected to empirical examination. There is contradictory evidence and also theoretical models with regard to that (Brunello 2004; Wolbers 2005; Culpepper and Thelen 2008).

The work of Esping-Andersen and Hall & Soskice has been followed by a vibrant strand of comparative research emphasizing the linkages between different types of welfare regimes, or alternatively production regimes, and education (and skills). For example, the influential concept of skill formation regimes—defined as a self-reinforcing configuration of institutions, or alternatively institutional packages, at the intersection among welfare state, labor market, and education and training systems—has been put forth in the VoC literature when examining development paths of different worlds of human capital formation and their sustainability over time and across countries. In this strand of research, scholars highlight the institutional complementarities between industrial relations, labour market institutions, production regime as well as welfare state and study their linkages and interconnections to explain variety in the emergence of different skill formation systems (Estevez-Abe et al. 2001; Iversen and Soskice 2001; Iversen and Stephens 2008; Mayer and Solga 2008; Busemeyer and Trampusch 2012; Busemeyer 2015).

From a comparative politics lens, Iversen and Stephens (2008) emphasise the mutually reinforcing relationships between skill formation, social protection systems and the role of the state. They distinguish three distinct types of human capital formation: liberal market regimes and coordinated market regimes, in which the latter are further subdivided into the social democratic regime and the Christian democratic regime. The liberal market regime is characterised by high private investments in general skills, a low level of public spending on active labour market policies (ALMP) and VET, as well as a low level of employment protection. This pattern results in skills polarisation, i.e. low levels of specific skills and of general skills at the bottom, but a high level of general skills at the top. The social democratic regime features heavy spending on public education, a well-developed VET system, advanced ALMP, and moderate levels of employment protection. Outcomes in terms of skills result in high levels of industry-specific and occupational-specific skills as well as general skills. The Christian Democratic regime is characterised by a well-developed VET system and high levels of employment protection, though, low levels of public spending on ALMP. High levels of employment protection have facilitated investment in firm- and industry-specific skills with skilled workers being favoured, whereas the interest of low-skilled workers being largely ignored and vulnerable to social exclusion. Iversen and Soskice (2001) emphasise the distinct character of political coalition formation underpinning each of the three regimes.

From the perspective of historical institutionalism, Busemeyer and Trampusch (2012) highlight the role of the state vs. private actors (households, market) in the provision and financing of VET as a crucial factor explaining the divergent development paths of skill formation regimes. Extending the two categories found in the VoC literature (liberal market regime and coordinated market regime) they propose a new category, namely collective skill formation systems, to which Austria, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland belong.

Referring to the characteristics of different skill formation regimes, they identify the following types:

-

the liberal skill regime demonstrating little public commitment or employer involvement, dominance of on-the-job training with no specific (or weakly developed) vocational tracks in general schools;

-

the statist skill regime featuring medium to strong public commitment to VET, but little employer involvement (due to crowding out effects), integration of VET into general school systems and academic drift;

-

the segmentalist skill regime providing often quite broad training, but in a firm-specific setting, with labour market mobility limited to internal labour markets and little public commitment, resulting in the delegation of VET to firms;

-

the collective skill regime featuring high involvement of employers and unions in governance and—partly—financing of skill formation and a strong role for intermediary associations.

This typology allows for explaining the evolvement of divergent development paths and cross-national variation as a product of historical path dependencies and critical junctures.

Other important areas of research have long suggested with evidence the importance of education, training, and skills from a system level perspective. Not least among these, is the economics of education, particularly the theory of human capital, which has and continues to play a powerful role in conveying the economic value of education, training and skills, namely by revealing their monetary returns in terms of earnings and employability effects as well as labour market mobility (Becker 1993; Hanushek et al. 2015, 2017). Research in the sociology of education has consistently revealed the consequences of inequality of access to quality education and learning in terms of equity, inclusion, well-being and a well-functioning society (Torres and Morrow 1995; Allmendinger and Leibfried 2003; UNESCO 2013, 2018). These multi-disciplinary research strands have stimulated empirical work that focuses more directly on effects of adult education and training. Research on the wider benefits of learning over the lifespan (Bynner et al. 2003; Feinstein und Hammond 2004; Field 2009) added considerably to these perspectives with evidence. Recent work highlights specific outcomes of participation in adult learning, both monetary and non-monetary, in terms of well-being, political participation and civic engagement (Ruhose et al. 2020; Gauly et al. 2020; for an overview: Schrader et al. 2020). Other intensively studied topics in the field concern inequalities of educational opportunities and the influence of social background on participation in (adult) education and training (Hadjar and Gross 2016; Blossfeld et al. 2020; Allmendinger et al. 2011; Cincinnato et al. 2016). Together, these strands of research have revealed the importance of widely extending diverse learning opportunities over the lifespan. In light of salient empirical evidence underlining the key role of education in the distribution of opportunities for participation in society and labour market, recent scholarship from the social investment perspective repositions education to the centre of social policy reforms (Kazepov et al. 2020) and addresses educational policies as part of an overall welfare state policy (Allmendinger and Nikolai 2010; Willemse and de Beer 2012).

2.3 New insights in the study of adult learning systems

The contribution of comparative political economy and welfare state research, in particular the typologies developed by Esping-Andersen (1990) as well as Hall and Soskice (2001) and their extensions and variants provided new insights in the way ALS can be perceived and inspired adult education research.

For example, Rubenson and Desjardins (2009) adopted the welfare state regimes framework to analyse the state’s role in shaping the broader structural conditions that are relevant for participation in adult education. They argue that participation in adult education is the result of the interplay between individual agency and structural conditions and that individual educational choices are constrained by institutions, leading to the concept of “bounded agency”. The type of welfare state regime influences both structural conditions and individual agency. Based on analysis of quantitative indicators (the amount of public and private education expenditure in connection to the distribution of competences), Allmendinger and Leibfried (2003) as well as Busemeyer (2015) provide further evidence for the degree of stratification in education systems in relation to partisan politics. Adapting Esping-Andersen’s theoretical approach Knauber and Ioannidou (2016) examine how different types of welfare state regimes develop and implement basic education policies for adults with low literacy skills focusing on the dimension of de-commodification.

The theoretical and methodological insights gained in particular from the VoC literature have stimulated the study of adult education and training from a political economy perspective. Specifically, the political economy of ALS has been developed as an offshoot of the debates on comparative welfare state research and considers contributions from different disciplinary perspectives (political science, the sociology of education, and economics of education) to understanding the causes and consequences of cross-national diversity in ALS across advanced industrialised nations and developed liberal democracies. A core argument in this research strand is that ALS are embedded in specific economic and social arrangements, ‘they lie at the intersection of a variety of other systems including a nation’s education and training system, labour market and employment system and other welfare state and social policy measures’ (Desjardins 2017, p. 232). As such, they are linked to a range of stakeholders (associations, chambers, communities of interest, industry) according to the historical origins of adult education and training in each country, the type of educational governance, and the type of skill formation regime.

The influence of culture, history, economic conditions and geopolitical developments on the formation of adult education and training systems as well as their embeddedness in a nation’s education system are well known issues in the field of adult education, particularly highlighted in comparative adult education research. However, analyses of the impact of institutional settings (or packages) in shaping ALS still represents a relatively small research strand, which mainly focuses on explaining differences in participation in adult learning (Roosmaa and Saar 2010; Saar et al. 2014; Blossfeld et al. 2014; Dämmrich et al. 2014; Kaufmann et al. 2014).

Looking at the political and institutional linkages between adult education and training and other institutions (labour market, welfare state, economy etc.), Desjardins (2017) reviews the extent and nature of adult learning structures that exist in different nation-states, considers the factors that explain the emergence of different adult learning system regimes and examines how these structures impact a range of economic and social outcomes. Building on the VoC literature, which suggests that a key feature of the comparative advantage of nation-states is the nature in which different institutional configurations enable the coordination of social problems, Desjardins suggests a typology on the variety of ALS in some of the most advanced industrialized economies. Looking from a governance perspective at patterns and mechanisms of coordination that underlie ALS, he distinguishes between market-led adult learning regimes, state-led regimes, stakeholder-led regimes and state-led regimes with a high degree of stakeholder involvement (Ibid., pp. 25–31). This typology is mainly based on the distinction between state vs market involvement on the existence (supply) and take-up (demand) of adult learning opportunities. To develop his typology Desjardins uses in depth analysis of country studies and combines them with quantitative macro data from large-scale assessments.

An important common feature in the political economy of skill formation regimes and ALS regimes is the emphasis put on “institutional packages” or “institutional complementarities”. Naturally, the variety of national institutional configurations of ALS is closely connected to that of skill formation systems, as ALS lie at the intersection of education and training systems, labour market institutions, and welfare systems. These nation-specific institutional packages affect patterns of coordination and can yield strikingly different outcomes both in terms of participation in adult education and in terms of political reforms (Saar et al. 2013).

Another common feature in typologies on skill formation and adult learning system regimes is that actors and actors’ constellations are to a certain degree similar, at least in the biggest segment of adult learning (Adult Vocational Education, AVE), which is job-related and employer-sponsored. Yet, there is a greater variety of stakeholders involved in the governance of ALS, especially in countries with well-developed Adult Liberal Education (ALE). The relative weight of AVE is also influenced by regime characteristics. In particular, intermediary associations involving non-market based stakeholder coordination are crucial in collective skill regimes (stakeholder-led or state-led with high degree of stakeholder involvement). Also, parties and partisan politics may have an impact on the evolution of distinctive ALS as well as on patterns of coordination and governance. However, and in contrast with extended literature from comparative public policy and welfare state research, their influence, have not been studied yet. Literature reveals that partisan politics have an impact on the evolution of specific skill formation regimes, hence, the strength of partisanship varies across time: it seems to be more important in earlier periods of historical development and critical junctures (Busemeyer 2015, pp. 123–174). It is further argued that institutions with their path dependencies and veto players matter (with regard to VET systems see Thelen 2004; with regard to lifelong learning see Ioannidou 2010).

The typologies that emerged out of comparative welfare state and political economy research have widely contributed to new theoretical and methodological insights to the study of adult education and training systems. Obviously, a key shortcoming of these typologies developed in other disciplinary contexts is a systematic integration of more specific institutional features that are more proximal to the take up, and provision of, organized adult learning. For example, the empirical cross-national patterns on the level of participation in organized adult learning, as presented in the following sections, do not neatly line up with the typologies mentioned in 2.2. This suggests a need to take account of specific institutional features that are more proximally related to organized adult learning, some of which are introduced and elaborated below as suggestions to develop these typologies for comparing ALS and to further this field of research.

3 Data and method of analysis

The analysis focuses on cross-national patterns revealed by available secondary sources of data and utilizes logical and structural forms of comparison of the patterns to draw out interpretations of the observed patterns (Ragin 1981). The purpose is not to identify causation, universal ‘truths’ or to generalize but to reveal differences and similarities in the patterns so as to elicit insights and nuances regarding structural and institutional features which are relevant to the comparative study of policy relevant factors related to the level and distribution of organized adult learning in selected advanced industrialized nations.

Data made available by the 2012 Survey of Adult Skills, a product of the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) as well as the 1994–1998 International Adult Literacy Survey (IALS) are used as sources to estimate cross-national patterns of organized adult learning. These are large scale comparative studies which were administered to nationally representative samples of adults aged 16 to 65 (large sample sizes ranging between 2000 to 5000 cases per country) (for details on study design see OECD 2013a; OECD and Statistics Canada 2000; for details on study quality see OECD 2013b; Murray et al. 1997). While these studies were primarily designed as international comparative assessments of literacy proficiency, IALS was effectively the first large scale international comparative study of adult learning ever undertaken which offers an important baseline measurement of the extent and distribution of adult learning in the 1990s for a wide range of OECD countries. As a follow up study, PIAAC collected in a comparable manner detailed information on a range of education and training activities undertaken by adults in the 12 months preceding the interview including formal education programmes and other non-formal learning activities such as workshops, seminars, on-the-job training as well as leisure and civic related courses. Therefore, with both datasets it is possible to empirically estimate the extent of growth in adult education since the 1990s. We follow the definition of organized adult learning as outlined above in detail in Sect. 2.1 in terms of non-traditional (adult) students and different types of organized adults learning. Furthermore, PIAAC collected the age at which adults completed their highest qualification which is used to estimate the proportion of adults who attained their highest qualification as non-traditional students as defined above in Sect. 2.1 (also see note for Fig. 4 for specific ages used to define non-traditional students).

The countries included in the analysis are those that participated in the 2012 OECD PIAAC and for which the data was made available, as well as for those that participated in both IALS and PIAAC. For the purposes of this analysis, countries that participated in later cycles of PIAAC were not included since the 2012 sample provides ample variation in terms of regions and in terms of the key variables considered.

Additionally, data made available by the 2011 OECD Aggregated Social Expenditure database, which roughly corresponds to the 12-month period in which the PIAAC data was collected, is used as the source of comparable data for social expenditures including total welfare spending, public spending on education, public spending on active labour market programmes and public assistance and housing.

4 The empirical evidence on cross-national patterns of organized adult learning

This section presents some of the empirical evidence on cross-national patterns of organized adult learning.

Participation rates in different types of organized adult learning based on PIAAC data are reported in Fig. 1, whereas Fig. 2 provides estimates of the growth of participation in organized adult learning since the 1990s using comparable data from IALS. Both surveys allow for a distinction between job- and non-job-related organized adult learning as well as whether the participation was employer-supported. The pattern as can be seen in Fig. 1 overwhelmingly suggests that the majority of organized adult learning is in some way employer-supported, is job-related, and is non-formal. Another key point is that the extent to which employers are supporting formal adult education (that leads to qualifications) has become rather substantial (i.e. 5–9% of the adult population) in nine out of 21 countries.

Annualized growth rate of organized adult learning between PIAAC (2012) and IALS (1990s). (Source: Own calculations based on the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC), 2012; and, International Adult Literacy Survey, 1994–1998. Annualized growth rate for each country that participated in both IALS and PIAAC was calculated by the percentage change in participation rates from IALS to PIAAC and divided by the number of years between the surveys)

In terms of trends over the approximate 20-year interim period (depending on country) shown in Fig. 2, several findings stand out.

First, the growth of participation rates in organized adult learning has been remarkable. All countries demonstrate a substantial increase in the proportion of adult populations who participate in organized adult learning on an annual basis, which implies major growth in the provision of organized learning opportunities. Even if calculations based on data from two different times are not enough to establish a trend, estimates of the annualized growth rate of participation based on the annual EU Labour Force Survey (LFS) data confirm the sharp growth (see Desjardins 2017, Table 12.1, pp. 185).

Second, many countries are catching up with the Nordic countries in terms of participation in organized adult learning. Countries that featured already comparatively high rates in the 1990s like Sweden, Finland, and Denmark, have been growing at a slower pace. Notably, the Netherlands, US, UK, and Canada have all grown at a faster pace, and nearly catching up to the Nordic countries. Other countries that had low rates of participation in the 1990s have experienced very high rates of growth estimated to be around 5% per annum. The only country that had a very low rate in the 1990s and did not experience growth is Italy.

Third, employer-supported organized adult learning is growing at a significantly higher pace in all countries.

Separate analyses have revealed that the overall growth of organized adult learning has significantly narrowed inequality in overall participation between various socially disadvantaged vs advantaged groups (i.e. young-old, low SES-high SES, low educated-high educated) in most countries including the market-led regimes such as US and the UK (Desjardins and Kim 2019). Some specific institutional features as well as government policies and programmes may have incentivized employers’ investment in disadvantaged workers; though, this cannot readily be ascertained from the PIAAC data.

Taken together, the cross-national patterns that emerge from Figs. 1 and 2 as well as other analyses reveal that the above-mentioned typologies in the preceding section do not sufficiently explain the observed variation in the extent and distribution of participation in organized adult learning. A number of countries (about 10) now appear to display similar patterns in terms of the extent and distribution of overall participation. Yet, many of these countries continue to vary substantially in terms of their institutional variation related to the welfare state, including the level of social expenditures that make up the welfare state. In particular, countries like the US and the UK which are often conceived as being more closely aligned with the market-led (or neoliberal) regime have rapidly caught up with the Nordic countries which are often conceived as being more closely aligned with the state-led model with a higher degree of stakeholder involvement (or social democratic) regime.

As put forth by Esping-Andersen (1998), it is not just the size of the welfare state, as measured by level of welfare spending, that can matter for distributional outcomes such as access to organized learning opportunities but also the composition of spending—what is emphasized and who gets the benefits. Indeed, the data highlight a weak overall relationship between the level of welfare spending and the probability of participation for the most disadvantaged groups. As can be seen in Fig. 3, the relationship between the overall level of welfare state expenditures and the proportions of adults who attained their highest qualifications as older adult learners (i.e. non-traditional students) is not uniform. The pattern reveals a weak overall relationship between the level of welfare spending and the proportions of adults who attained their highest qualifications as adult learners.

Total welfare spending and proportion of adults with lowest educated parents who attained highest qualifications as an adult learner. (Source: Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC), 2012; OECD Aggregated Social Expenditure Database (2011). Adults with lowest educated parents are defined as those with both parents having attained less than upper secondary education. Total welfare spending as per OECD Aggregated Social Expenditure Database includes: old age survivor, disability; health; family and housing; unemployment; active labour market programmes; and, other (fractional proportion). It does not include public spending on education)

The countries that are most successful in extending organized adult learning opportunities to the most disadvantaged feature the highest levels of welfare state expenditures (upper right quadrant). These are also the countries that demonstrate the highest levels of overall participation (as shown in Fig. 1)—Denmark, Finland and Sweden. Norway is similar to the other Nordic countries especially when taking into account the non-standard level of its GDP as consequence of its oil industry. There is also a range of countries in the lower left quadrant of Fig. 3 that spend less on average on welfare programmes and feature low levels of participation in organized adult learning in general, and among the most disadvantaged adults (defined as adults with both parents having attained less than upper secondary education) in particular. However, there are a number of countries in between. The Netherlands is a country that features relatively high and widely distributed levels of organized adult learning but its overall welfare spending is less than Italy’s by about 4%. In contrast, Italy features among one of the lowest levels of participation in organized adult learning. Similarly, Austria, Belgium, France and Germany feature high overall levels of welfare state expenditures but lag Canada, Ireland, the UK and US in terms of extending organized adult learning opportunities to the most disadvantaged, even though the latter are below average spenders on all types of welfare programmes.

In summary, the data focusing on the take up and distribution of organized adult learning reveal shortcomings in the explanatory framework of the typologies discussed above in terms of explaining variation in the cross-national patterns. The next section considers some institutional features that are more proximal to the take up, provision and distribution of organized adult learning.

5 Some institutional features that are more proximal to ALS

In the explanatory framework of the political economy of ALS, institutional features such as those relating to education, labour market or welfare state and associated public policy frameworks, including their absence, play an important role in mitigating or exacerbating inequalities in adult learning. This can be a direct consequence, whereby policies are devised to intentionally address such problems with ad-hoc measures like one-off subsidies or specific programmes, but it can also be an indirect consequence since specific institutional features can affect the existence (supply) and take-up (demand) of organized adult learning opportunities in unintended ways (Desjardins 2017, p. 32).

Several specific institutional features can play a role in fostering high and widely distributed levels of participation in organized adult learning. A challenge for comparative research is to integrate these into the typologies already discussed in a more systematic manner by linking the different perspectives from various disciplines. The focus here is to outline some key institutional features that might considered in order to further this field of research.

A closer look at the composition of welfare spending in a way that distinguishes between categories that are deemed to be more proximal or distal to organized adult learning is revealing. As an example, Austria, Belgium, France, Germany and Italy’s welfare expenditures (as per the OECD Aggregated Social Expenditure Database for year 2011) tends to be concentrated on old age and health benefits, especially when compared to Canada, Ireland, the UK and the US. These are categories that can be considered as more distal to adult learning.

The following focuses on a number of institutional features that are more proximal to ALS and enable the provision, take up and distribution of organized adult learning: open and flexible formal education structures, public support for education, active labour market policies and programmes that target socially disadvantaged adults.

5.1 Open and flexible education structures

The extent to which adults can attain qualifications at older ages reflects the “openness” and “permeability” of the formal education structures as well as their “flexibility” in catering to the needs of non-traditional students. Fig. 4 highlights that open and flexible education structures that cater to needs of adult learners, specifically non-traditional students as defined above, is a key feature explaining overall participation rates. In several countries (Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Canada and the United States), more than a quarter of the population attained their highest qualification as a non-traditional student, which also tend to be the countries with the highest overall rates of participation in organized adult learning.

Percent of adults who attained their highest qualification as non-traditional students. (Source: Own calculations based on the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC), 2012. Non-traditional students are defined as adults who completed: ISCED 2 or lower at age 19 or older; ISCED 3 or 4 at age 21 or older; ISCED 5b or 5A (BA) at 26 or older; and, ISCED 5a (MA or PhD) at age 30 or older)

The integration of adults into the formal education system where possible or access to equivalent qualifications affects their motivation and shows high returns in terms of both employment probabilities and income growth (Kilpi-Jakonen and Sirniö 2020). Adult learning activities that can be linked to qualifications motivate, whether the undertaking is formal or non-formal, because they communicate value among stakeholders, and thus enhance the labour market value of investing in adult learning (Singh 2015; Singh and Duvekot 2013). This has knock-on effects promoting continued adult learning because there is a direct relation between higher levels of qualifications and continued learning throughout the lifespan (Desjardins et al. 2006; Rubenson 2018). However, creating parallel non-formal systems or lower tier tracks can have adverse effects on individual benefits and in turn, on individual motivation if they are associated with lower status and stigma.

The extent to which non-formal adult learning activities can be linked to qualification systems, for example via the Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) mechanisms, is crucial as it allows for much greater flexibility and permeability to cater to the needs of diverse groups by enabling customization, targeting and outreach. Countries that continually develop their adult learning provision structures in terms of “integrating opportunities” to seamlessly connect them to all kinds of formal qualifications are more successful in boosting participation, skills, assuring quality of the programmes and enhancing the value of adult learning.

5.2 Public support for education combined with open and flexible education structures

In contrast to total welfare spending, public spending on education has a stronger relationship with organized adult learning related outcomes but this is not straightforward. Specifically, the level of public spending on education tends to be related to higher and more widely distributed levels of organized adult learning on the condition that formal systems are more open and flexible to adults. Simply put, in many countries, public support for education does not benefit access to organized adult learning because the formal educational structures are closed off to adults and tend to be reserved for younger adults who follow the traditional front loaded and most direct path to their highest qualification. However, in countries where these structures are more flexible and accommodate adults, then public support for education including those for regular formal educational structures may be more successful in reaching adults, particularly those who are disadvantaged and could not follow the more traditional front-loaded path.

Fig. 5 shows the relationship between public spending on education and the probability of participation in organized adult learning for adults with both parents having attained less than upper secondary education. The patterns suggest that countries with higher public expenditures on education are successful in boosting qualifications for the disadvantaged but this seems at least partly contingent on having flexible educational structures that accommodate adults that did not follow the traditional front-loaded path. Canada, the UK and the US, along with Ireland spend more or similar on public education compared to Germany and Spain and a range of other countries who are less successful in extending opportunities to the most disadvantaged. Austria, Belgium and France are above average spenders on public education but this does not translate into higher rates of participation. This might be related to the fact that the formal education systems in those countries are less open to older adults as was shown in Fig. 4. In contrast, the Nordic countries along with the Netherlands, Canada, US and UK, closely followed by Germany and Spain, feature formal education systems that are more open to adult learners, which is consistent with their above average success in boosting participation and extending opportunities to a wider range of adult learners as shown in Fig. 1.

5.3 Active labour market policies

Active Labour Market Policies (ALMPs) can interact with organized adult learning and are specifically designed to boost employment. In their most basic form, ALMPs typically comprise of public employment services including job centres and labour exchanges, which improve job-searching efforts. Such employment services may simply help with developing skills to obtain a job such as interview skills or writing curriculum vitae. Nevertheless, they may also be more directly connected to organized adult learning by offering training schemes, such as courses or apprenticeships, or other formal programmes, to boost employability. As such, depending on how they are operationalized, ALMPs may form an important part of ALS. In contrast, ALMPs can simply involve employment subsidies and thus be limited in their relationship to organized adult learning, especially if there are limited provision structures related to organized adult learning (including “closed” formal education structures). Some countries like Denmark, Finland, Sweden and the Netherlands provide public support for the unemployed to participate in organized adult learning provisions that already exist and as such, ALMPs of this kind form an important part of ALS in those countries.

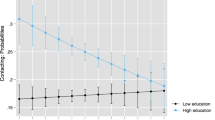

As can be seen in Fig. 6, not all spending on ALMPs seems to be equally effective in boosting participation, particularly among adults with the lowest levels of education. Results show that whereas France, Ireland and Spain are above average spenders on ALMPs, this does not necessarily lead to success in boosting participation among those with lower levels of education (ISCED 3 or below). In contrast, Australia, Canada, the Czech Republic, the United States and New Zealand spend relatively little on these programmes, but feature above average levels of participation among those with lower levels of education. A key point is that ALMPs do not necessarily relate to participation in organized adult learning because it depends on the prevalence of related provision structures, including how open and flexible the ALS is and how well it is catering to the needs of disadvantaged adults. Therefore, the extent to which welfare-spending categories like ALMPs actually aim to foster participation of a particular kind matters. For example, the ALMP programmes in the Nordic countries are designed to provide working age adults access to organized adult learning and often lead to formal qualifications.

5.4 Targeting

Policies related to customization, targeting and outreach are an indication of active policy making that seeks to boost the level and equitable distribution of organized adult learning. Targeting and outreach, especially for adults with little or no qualifications, are crucial tools for tackling inequality and disadvantage. They imply non-market-based solutions, based on state aims related to equity and social justice, not necessarily market or narrow stakeholder interests.

Public spending on family assistance can be seen as a proximal factor to organized adult learning to the extent that it may help disadvantaged adults to overcome barriers to participation. This type of spending can be helpful for addressing structural constraints to participation relating to family and other situational-based constraints (as discussed in Rubenson and Desjardins 2009).

As shown in Fig. 7, public spending on family assistance shows a stronger relationship to cross-national participation patterns compared, for example, to overall welfare spending as shown in Fig. 3. It can be seen that Ireland and the UK register relatively high spending in this category, which is consistent with the relatively higher participation rates of the most disadvantaged in those two countries.

6 Conclusions

This article provides an overview of the state of art in the study of adult learning systems from a political economy perspective. Our review of typologies that have emerged out of the field of comparative economics and comparative politics in Sect. 2 has shown that these fields have contributed powerful theoretical concepts and triggered interdisciplinary empirical research on the impact of institutional settings and institutional packages on Adult Learning Systems (ALS). Typologies allow not only the clustering of countries along specific institutional features but also the empirical validation of hypotheses derived by the theory. Research so far has mainly focused on explaining differences in participation in adult education, whereas very little scholarship has dealt with exploring variation on the grounds of existing institutional complementarities and how the latter affect patterns of coordination and outcomes of ALS.

Our brief overview of some of the most salient patterns of participation in organized adult learning across countries in Sect. 4 based on analysis of PIAAC data suggests that existing typologies of welfare state regimes or skills formation systems are insufficient to explain variation in the cross-national patterns. A range of countries appear to display similar patterns in terms of the extent and distribution of overall participation, particularly as ALS have grown rapidly in the last 20 years. Yet, many of these countries continue to vary substantially with regard to their overall institutional variation related to the type of welfare state. We argue that there are some institutional features that are more directly related to the provision, take up and distribution of organized adult learning. Our analysis in Sect. 5 reveals that it is not just public spending on education or total welfare spending that matter, but rather structural factors relevant to social policy, institutional and public policy frameworks seem to play a prominent role in explaining the patterns of participation in organized adult learning. We focus our discussion on a number of institutional features that are more proximal to organized adult learning and argue that these features can play a role in fostering high and widely distributed levels of participation in adult learning: open and flexible formal education structures, public support for education, active labour market policies and programmes that target socially disadvantaged adults. Countries that feature high and widely distributed levels of participation in organized adult learning can be seen as those with the most effective ALS.

The role of the state is particularly important for balancing the interests of diverse social groups and to mitigate inequalities. There is plenty of evidence to suggest that participation in organized adult learning varies considerably according to individual-level characteristics such as age, education, gender, occupation (Blossfeld et al. 2014; Boeren and Holford 2016; Lee and Desjardins 2019). Those who are already better educated and those with relatively secure professional positions are cumulatively expanding their lead even further through additional investment in adult learning, the so-called Matthew principle (Boeren 2009; Blossfeld et al. 2020; Ioannidou et al. 2020). Research findings to date also confirm that, for a number of reasons, companies support those employees in their competence development who already possess higher skills. Therefore, if employers and workers are left to their own, they will almost automatically commit themselves to behavioural patterns that exacerbate inequalities. A key contextual condition underlying effective ALS is the degree of state involvement via public and social policies as well as stakeholder involvement via an inclusion of social partners; in other words, the type of governance of ALS matters.

The use and extent of social policy instruments (a form of non-market coordination) can be crucial to foster the development of adult learning opportunities (e.g. public spending in open and flexible education systems, ALMPs, targeting) as well as to enable adults to overcome the various structural constraints associated with those opportunities (e.g. family assistance, childcare). No less important is the use of public policies and stakeholder arrangements (forms of non-market coordination) to influence the skill orientation of the economy by emphasising both an increase in the supply of skills as well as incentives to use skills in production in ways that boost innovation and productivity. Several studies demonstrate a strong link between the skill orientation of the economy and the extent and distribution of adult learning opportunities (OECD 2012; Desjardins 2017).

From a comparative political-economy perspective a common and pressing challenge for all ALS is how to cope with major upheavals in the future of work by automation and digitization and the socio-ecological transformation towards more sustainability (e.g. farewell to the lignite industry). Even if we do not yet know whether the jobs created will eventually balance out those destroyed, as was the case with previous technological revolutions, there can be little doubt that dislocations are likely to be substantial and mass unemployment will probably loom in certain countries, regions and industries. The provision of adult learning opportunities to ensure ‘reskilling’ will be a major challenge for ALS and will necessitate coordinated public policy responses, a high level of investment in skills and political commitment from all stakeholders.

Given the positive monetary and non-monetary outcomes of participation in adult learning, however, this is a worthy undertaking. Indeed, many countries who feature high and widely distributed levels of organized adult learning have well-developed governance structures that foster coordination among stakeholders; financing structures that align incentives and foster co-investment; and provision structures that enable open, flexible and targeted opportunities that are designed to mitigate barriers to participation. Policy makers thus have at their disposal several tools to help citizens overcome barriers to participation, ranging from broad social policies to economic and labour market policies.

Change history

31 August 2020

In the Editorial of this issue, Miroslav Stefanik was accidentally stated as the single author of the article “Multi-layered Perspective on the Barriers to Learning Participation of Disadvantaged Adults”. The article is a joint authorship by <Emphasis Type="Italic">Sofie Cabus, Petya Ilieva-Trichkova and Miroslav Stefanik</Emphasis>

References

Allmendinger, J., & Leibfried, S. (2003). Education and the welfare state: the four worlds of competence production. Journal of European Social Policy, 13(1), 63–81.

Allmendinger, J., & Nikolai, R. (2010). Bildungs- und Sozialpolitik: Die zwei Seiten des Sozialstaats im internationalen Vergleich. Soziale Welt, 61(2), 105–119.

Allmendinger, J., Kleinert, C., Antoni, M., Christoph, B., Drasch, K., Janik, F., Leuze, K., Matthes, B., Pollak, R., & Ruland, M. (2011). Adult education and lifelong learning. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 14(2), 283–299.

Arts, W., & Gelissen, J. (2002). Three worlds of welfare capitalism or more? A state-of-the-art report. Journal of European Social Policy, 12(2), 138–158.

Becker, G. S. (1993). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education (3rd edn.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Blossfeld, H.-P., Kilpi-Jakonen, E., Vono de Vilhena, D., & Buchholz, S. (2014). Adult learning in modern societies: an international comparison from a life-course perspective. (EduLIFE lifelong learning). Cheltenham, Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Blossfeld, H.-P., Kilpi-Jakonen, E., Vono de Vilhena, D., & Buchholz, S. (2020). Is there a Matthew effect in adult learning? Results from a cross-national comparison. In J. Schrader, A. Ioannidou & H.-P. Blossfeld (Eds.), Monetäre und nicht monetäre Erträge von Weiterbildung – Monetary and non-monetary effects of adult education and training. Edition ZfE, Vol. 7. Wiesbaden: VS.

Boeren, E. (2009). Adult education participation: the Matthew principle. Filosofija Sociologija, 20(2), 154–161.

Boeren, E., & Holford, J. (2016). Vocationalism varies (a lot). A 12-country multivariate analysis of participation in formal adult learning. Adult Education Quarterly,, 66(2), 120–142.

Brown, P., Green, A., & Lauder, H. (2001). High skills. Globalization, competitiveness, and skill formation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brunello, G. (2004). Labour market institutions and the complementarity between education and training in europe. In D. Checchi & C. Lucifora (Eds.), Education, training and labour market outcomes in Europe (pp. 188–210). London: Palgrave Macmillian.

Busemeyer, M. R. (2015). Skills and Inequality. Partisan politics and the political economy of education reforms in western welfare states. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Busemeyer, M. R., & Trampusch, C. (2012). The political economy of collective skill formation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bynner, J., Schuller, T., & Feinstein, L. (2003). Wider Benefits of education: skills, higher education and civic engagement. Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, 49(3), 341–361.

Cincinnato, S., de Wever, B., van Keer, H., & Valcke, M. (2016). The influence of social background on participation in adult education: applying the cultural capital framework. Adult Education Quarterly, 66(2), 143–168.

Culpepper, P. D., & Thelen, K. (2008). Institutions and collective actors in the provision of training. Historical and cross-national comparisons. In I. K. U. Mayer & H. Solga (Eds.), Skill Formation. Interdisciplinary and cross-national perspectives (pp. 21–49). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Dämmrich, J., Vono, D., & Reichart, E. (2014). Participation in adult learning in Europe: the impact of country-level and individual characteristics. In H.-P. Blossfeld, E. Kilpi-Jakonen, D. Vono de Vilhena & S. Buchholz (Eds.), Adult learning in modern societies: patterns and consequences of participation from a life-course perspective (pp. 25–51). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Danforth, B. (2014). Worlds of welfare in time: a historical reassessment of the three-world typology. Journal of European Social Policy, 24(2), 164–182.

Desjardins, R. (2017). Political economy of adult learning systems. Comparative study of strategies, policies and constraints. London: Bloomsbury.

Desjardins, R. (2018). Economics and the political economy of adult education. In M. Milana, S. Webb, J. Holford, R. Waller & P. Jarvis (Eds.), The Palgrave international handbook on adult and lifelong education and learning (pp. 211–226). Houndsmill: Palgrave Macmillan.

Desjardins, R., Rubenson, K., & Milana, M. (2006). Unequal chances to participate in adult learning: International perspectives. Fundamentals of Educational Planning Series. Paris: UNESCO International Institute of Educational Planning.

Desjardins, R., & Kim, J. (2019). The growth of employer-supported adult education and its role in mitigating unequal chances to participate. Unpublished manuscript.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). Three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1998). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Estevez-Abe, M., Iversen, T., & Soskice, D. (2001). Social protection and the formation of skills: a reinterpretation of the welfare state. In P. Hall & D. Soskice (Eds.), Varieties of capitalism. The institutional foundations of comparative advantage (pp. 1–47). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Feinstein, L., & Hammond, C. (2004). The contribution of adult learning to health and social capital. Oxford Review of Education, 30(2), 199–221.

Ferragina, E., & Seeleib-Kaiser, M. (2011). Welfare regime debates: past, present, futures? Policy and Politics, 39(4), 583–611.

Ferrara, M. (1996). The southern model of welfare in social Europe. Journal of European Social Policy, 6, 179–189.

Field, J. (2009). Good for your soul? Adult learning and mental well-being. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 28(2), 175–191.

Gauly, B., Lechner, C., & Reder, S. (2020). Does job-related training benefit adult numeracy skills? Evidence from a German panel study. In J. Schrader, A. Ioannidou & H.-P. Blossfeld (Eds.), Monetäre und nicht monetäre Erträge von Weiterbildung – Monetary and non-monetary effects of adult education and training. Edition ZfE, Vol. 7. Wiesbaden: VS.

Hadjar, A., & Gross, C. (2016). Education systems and inequalities. International comparisons. Bristol: Policy Press.

Hall, P., & Soskice, D. (2001). Varieties of capitalism. The institutional foundations of comparative advantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hanushek, E. A., Schwerdt, G., Wiederhold, S., & Woessmann, L. (2015). Returns to skills around the world: evidence from PIAAC. European Economic Review, 73, 103–130.

Hanushek, E. A., Schwerdt, G., Woessmann, L., & Zhang, L. (2017). General education, vocational education, and labor-market outcomes over the life-cycle. Journal of Human Resources, 52(1), 48–87. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.52.1.0415-7074R.

Ioannidou, A. (2010). Steuerung im transnationalen Bildungsraum. Internationales Bildungsmonitoring zum Lebenslangen Lernen. Bielefeld: wbv.

Ioannidou, A., & Jenner, A. (2020). Regulation in a contested space: Economization and standardization in adult and continuing education. In I. S. Jornitz & A. Wilmers (Eds.), International perspectives on school settings, education policy and digital strategies: a transatlantic discourse in education research. Opladen: Budrich.

Ioannidou, A., Parma, A., & Matsaganis, M. (2020). Risk of job automation and participation in adult education and training: Exploring Matthew effects. Unpublished manuscript.

Iversen, T., & Soskice, D. (2001). An asset theory of social policy preferences. American Political Science Review, 95(4), 875–893.

Iversen, T., & Stephens, J. (2008). Partisan politics, the welfare state, and the three worlds of human capital formation. Comparative Political Studies, 41, 600–637.

Kaufmann, K., Reichart, E., & Schömann, K. (2014). Der Beitrag von Wohlfahrtsstaatsregimen und Varianten kapitalistischer Wirtschaftssysteme zur Erklärung von Weiterbildungsteilnahmestrukturen bei Ländervergleichen. Report – Zeitschrift für Weiterbildungsforschung, 37(2), 39–54.

Kazepov, Y., Cefalo, R., & Pot, M. (2020). A social investment perspective on lifelong learning: the role of institutional complementarities in the development of human capital and social participation. In I. M. P. d. Amaral, S. Kovacheva & X. Rambla (Eds.), Lifelong learning policies for young adults in Europe. Navigating between knowledge and economy (pp. 43–62). Bristol: Policy Press.

Kilpi-Jakonen, E., & Sirniö, O. (2020). Formal adult education and labour market inequalities in Finland. In J. Schrader, A. Ioannidou & H. P. Blossfeld (Eds.), Erträge von Weiterbildung. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft – Sonderheft. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer.

Knauber, C., & Ioannidou, A. (2016). Politiken der Grundbildung im internationalen Vergleich: von der Politikformulierung zur Implementierung. Report – Zeitschrift für Weiterbildungsforschung, 39, 131–148.

Lee, J., & Desjardins, R. (2019). Inequality in adult learning and education participation: the effects of social origins and social inequality. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 38(3), 339–359.

Mayer, K. U., & Solga, H. (2008). Skill formation. Interdisciplinary and cross-national perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Meyer, J., & Ramirez, F. (2003). The World Institutionalization of Education. In J. Schriewer (Ed.), Discourse formation in comparative education (pp. 111–132). Bern: Peter Lang.

Murray, T. S., Kirsch, I. S., & Jenkins, L. B. (1997). Adult literacy in OECD countries: technical report on the first international adult literacy survey (NCES 98-053). U.S. Department of education, national center for education statistics. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs98/98053.pdf.

OECD (2012). Better skills, better jobs, better lives. A strategic approach to skills policies. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD (2013a). OECD skills outlook 2013: first results from the survey of adult skills. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD (2013b). The survey of adult skills: reader’s companion. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD, & Statistics Canada (2000). Literacy in the information age: final report on the international adult literacy survey. Paris, Ottawa: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and Statistics Canada.

Powell, M. (2015). A re-specification of the welfare state: conceptual issues in the three worlds of welfare capitalism. Social Policy & Society, 14(2), 247–258.

Ragin, C. (1981). Comparative sociology and the comparative method. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 22(1–2), 102–117.

Rees, G. (2013). Comparing adult learning systems. An emerging political economy. European Journal of Education, 48(2), 200–212.

Rice, D. (2013). Beyond welfare regimes: from empirical typology to conceptual ideal types. Social Policy and Administration, 47(1), 93–110.

Roosmaa, E.-L., & Saar, E. (2010). Participating in non-formal learning. Patterns of inequality in EU-15 and the new EU‑8 member countries. Journal of Education and Work, 23(3), 179–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2010.486396.

Rubenson, K. (2018). Conceptualizing participation in adult learning and education: equity issues. In M. Milana, S. Webb, J. Holford, R. Waller & P. Jarvis (Eds.), The Palgrave international handbook on adult and lifelong education and learning (pp. 337–357). Houndsmill: Palgrave Macmillan.

Rubenson, K., & Desjardins, R. (2009). The impact of welfare state regimes on barriers to participation in adult education: a bounded agency model. Adult Education Quarterly, 59(3), 187–207.

Ruhose, J., Thomsen, S., & Weilage, I. (2020). Work-related Training and Subjective Well-being. Estimating the Effect of Training Participation on Satisfaction, Worries and Health in Germany. In J. Schrader, A. Ioannidou & H.-P. Blossfeld (Eds.), Monetäre und nicht monetäre Erträge von Weiterbildung – Monetary and non-monetary effects of adult education and training. Edition ZfE, Vol. 7. Wiesbaden: VS.

Saar, E., Ure, O. B., & Desjardins, R. (2013). The role of diverse institutions in framing adult learning systems. European Journal of Education, 48(2), 213–232.

Saar, E., Ure, O. B., & Holford, J. (2014). Lifelong learning in Europe. National patterns and challenges. Cheltenham: and Northhampton, MA, US. Edward Elgar Pub.

Schrader, J., Ioannidou, A., & Blossfeld, H.-P. (2020). Wirkungen der Erwachsenen- und Weiterbildung: Zugänge und Befunde der empirischen Bildungsforschung. In J. Schrader, A. Ioannidou & H.-P. Blossfeld (Eds.), Monetäre und nicht monetäre Erträge von Weiterbildung – Monetary and non-monetary effects of adult education and training. Edition ZfE, Vol. 7. Wiesbaden: VS.

Singh, M. (2015). Global perspectives on recognising non-formal and informal learning. Why recognition matters. Hamburg, Cham: UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning, Springer.

Singh, M., & Duvekot, R. (2013). Linking Recognition Practices and National Qualifications Frameworks. International benchmarking of experiences and strategies on the recognition, validation and accreditation (RVA) of non-formal and informal learning. Hamburg: UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning.

Thelen, K. (2004). How institutions evolve. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Torres, C. A., & Morrow, R. A. (1995). Social theory and education. A critique of theories of social and cultural reproduction. New York: State University of New York Press.

UNESCO (2013). Inequalities in Education. In UNESCO (Eds.), Education For All Global Monitoring Report, 1–18. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000220440. Accessed March 15, 2020.

UNESCO (2018). Ensuring the right to equitable and inclusive quality education: results of the ninth consultation of Member States on the implementation of the UNESCO Convention and Recommendation against Discrimination in Education. Paris: UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000251463

Willemse, N., & De Beer, P. (2012). Three worlds of educational welfare states? A comparative study of higher education systems across welfare states. Journal of European Social Policy, 22(2), 105–117.

Wolbers, M. H. J. (2005). Initial and further education: substitutes or complements? International Review of Education, 51(5–6), 459–478.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Desjardins, R., Ioannidou, A. The political economy of adult learning systems—some institutional features that promote adult learning participation. ZfW 43, 143–168 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40955-020-00159-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40955-020-00159-y

Keywords

- Political economy of adult learning systems

- Welfare state research

- Adult learning participation

- Comparative research