Abstract

COURSE50 (CO2 Ultimate Reduction in Steelmaking process by innovative technology for cool Earth 50) aims to increase the proportion of hydrogen reduction in the blast furnace. This objective raises the key issue of heat balance changes in individual regions as well as in the overall blast furnace. In order to compensate for the endothermic reactions of hydrogen, a decrease in direct reduction by carbon, a huge endothermic reaction, is being executed. Among the various hydrogen sources available in the industry, coke oven gas (COG) was chosen because of its availability and stability. However, COG requires reforming for it to be injected into the shaft of the blast furnace because this zone cannot combust the hydrocarbon components of COG. COURSE50 has carried out successful COG and reformed COG injection trials at LKAB’s experimental blast furnace in Luleå, Sweden, in cooperation with LKAB and Swerea MEFOS. Carbon consumption in both the COG and reformed COG injection periods decreased compared with the base period because of the planned increase in hydrogen reduction instead of direct reduction by carbon. These results indicate the possibility of increasing the amount of hydrogen reduction in the blast furnace.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Preface

Since FY2008, we have promoted technology development through the innovative COURSE50 (CO2 Ultimate Reduction in Steelmaking process by innovative technology for cool Earth 50) R&D program [1–6], which aims at mitigating CO2 emissions in the ironmaking process. Figure 1 shows an outline of the COURSE50 project and its two major research activities.

Outline of COURSE50 [11]

COURSE50 is a Japanese national project aimed at the development of technologies for environmentally harmonized steelmaking processes to achieve a drastic reduction in CO2 emissions in the steel industry. The consortium consists of five partners: Kobe Steel Ltd., JFE Steel Corporation, Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal Corporation, Nippon Steel & Sumikin Engineering Co. Ltd., and Nisshin Steel Co. Ltd., and the project was initiated within The Japan Iron and Steel Federation and financed by New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization. The project started in FY2008, and Step 1 of Phase 1 was completed in FY2012. Step 2 of Phase 1 will be completed in FY2017.

The main targets of the COURSE50 project are the development of technologies to reduce CO2 emissions from the blast furnace and the development of technologies to capture, separate, and recover CO2 from blast furnace gas (BFG). CO2 reduction technology for the blast furnace consists of research into the control of reactions for reducing iron ore using hydrogen-rich reducing agents such as coke oven gas (COG) or reformed COG (RCOG). The hydrogen content of COG is amplified in RCOG by utilizing a newly developed catalyst and unused waste heat. Moreover, a technology to produce high-strength and high-reactivity coke for blast furnaces with increased hydrogen reduction is under development. RCOG will be injected into the blast furnace through the tuyeres located above the belly in the lower part of the shaft of the blast furnace, or COG will be injected through the normal blast tuyeres to utilize CH4 combustion. COG cannot be usefully injected into the shaft as its hydrocarbon content (mainly CH4) cannot be combusted there and may therefore be wasted. Because the hydrocarbon content in COG will inevitably be reformed to CO and H2 in the raceway, injection of RCOG into the blast tuyeres is not necessary.

General Overview of CO2 Mitigation Technologies for the Blast Furnace

The initial objective is the development of technologies to reduce CO2 emissions from blast furnaces by (1) the development of reaction control technologies to reduce iron ore using hydrogen (producing H2O rather than CO2 in the blast furnace off-gas stream), (2) reforming technology for the application to COG, which increases the hydrogen content of the gas, and (3) technology to manufacture high-strength and high-reactivity coke suitable for hydrogen reduction blast furnaces.

Another objective is the development of technologies to capture CO2 from BFG through chemical and physical adsorption methods using waste heat available within the steelworks. The overall target for CO2 emission mitigation is approximately 30 % in the steelworks. The Step 1 project (2008–2012) for the development of basic technologies has been completed according to schedule, and now the development of comprehensive technologies is being undertaken in Step 2 (2013–2017).

An operating experimental blast furnace (EBF) located in Luleå, Sweden was used. It is owned by LKAB [7, 8], a Swedish mining company, and was constructed in 1997. LKAB’s EBF has successfully completed 25 campaigns including some trials to demonstrate the “ULCOS Top Gas Recycling Blast Furnace Process” [9], supported by Swerea MEFOS up until the winter of 2010. As the EBF has a relatively large diameter, consideration of the penetration behavior of gas injected into the shaft is possible, and COURSE50 decided to carry out a test campaign.

The main objectives of the EBF trial were to investigate and evaluate the potential of replacing coke and coal as reducing agents in the blast furnace with high H2-containing gas such as COG or RCOG.

Basic Concept of Hydrogen Reduction

Figure 2 shows the concept of iron ore reduction by hydrogen. The project is developing a technology to reduce CO2 emissions from the blast furnace through the reduction of iron ore using hydrogen-rich reducing agents such as COG or RCOG, which as an amplified hydrogen content is achieved through the use of a newly developed catalyst and unused 800 °C waste heat available from the coke ovens. In the case of increased reduction by H2 in the upper blast furnace, a decrease in carbon direct reduction is expected in the lower furnace. This is the main concept of the iron ore hydrogen reduction in COURSE50. Quantitatively, the increase in hydrogen reduction and decrease in carbon direct reduction are not proportional, and the blasting and raw material conditions must be considered carefully.

Concept of increased iron ore reduction by hydrogen in the blast furnace [11]

Experimental Conditions

Blast Furnace Facilities

Figure 3 shows a profile of LKAB’s EBF and some of its features. It has a working volume of 9.0 m3. The throat diameter (stock level) and hearth diameter are 1.0 m and 1.4 m, respectively. The EBF has three blast tuyeres, a unique bell-less charging system, ore and coke bins, and an injection system. Hot blast air can be heated by pebble heaters up to 1200 °C. Pulverized coal (PC), oil, or various gases can be injected from the blast tuyeres. Two horizontal shaft probes, upper and lower, measure the radial temperature distribution and can sample the material in the furnace. An inclined probe samples the material partly from the lower shaft and partly from the cohesive zone, and vertical descending probes measure the inner vertical temperature and pressure distribution from the top. The EBF is also specially equipped with upper and lower shaft tuyeres for the injection of hot gases.

As can be seen in Fig. 3, the levels of the burden, upper shaft tuyeres, lower shaft tuyeres, and blast tuyeres are 7.65, 6.20, 4.19, and 1.95 m from the hearth bottom level, respectively. The levels of the upper and lower shaft probes are 6.75 and 5.35 m from the hearth level, respectively. Thus, the upper shaft probe is located 0.90 m below the burden level and 4.80 m above the blast tuyeres, and the lower shaft probe is located 2.30 m below the burden level and 3.40 m above the blast tuyeres. The temperatures of the refractory lining and skinflow gases are measured by thermocouples.

Operational Conditions of the Blast and Gas Injection

Synthetic COG and RCOG were mixed from pure gases to maintain a constant and accurate gas composition throughout the trial operation for the main purpose of evaluating the effects of the H2 reaction. COG was injected from the blast tuyeres, and RCOG was injected from the three lower shaft tuyeres located 2.24 m above the blast tuyeres. The COG composition was 57 %H2–31.3 %CH4–11.7 %N2, and it was injected at a rate of 100 Nm3/t-hm (150 Nm3/h). The RCOG composition was 77.9 %H2–22.1 %N2, and it was injected at a rate of 150 Nm3/t-hm (225 Nm3/h). The volumes of input H2 in 100 Nm3 of COG and 150 Nm3 of RCOG are approximately the same. The details are given in Table 1.

RCOG was heated using a counter-current heat exchanger and then injected into the EBF through the lower shaft tuyeres. The heat exchanger consisted of two parts. In the upper counter-current heat exchanger, the flue gas from the combustion chamber flowed into the pipes while the surrounding RCOG was heated. RCOG then flowed into the pipes of the tube basket, which is the second co-current heat exchanger at a temperature of 650–760 °C, before reaching a maximum temperature of 925 °C. When RCOG was injected into the blast furnace, its temperature was around 800 °C because of heat loss. The diameter of the shaft tuyere was 32 mm, and the gas velocity was approximately 45 m/s at an injection rate of 225 Nm3/h. The penetration depth of RCOG into the furnace was detected using the lower shaft probe located 1.16 m above the shaft tuyere level [5].

The coaxial-type swirl tip lances installed in the blast tuyeres were used for the COG and PC injection. PC was injected from the central part of the lance with N2 as a carrier gas, and COG was injected from the outer part (annulus).

The top BFG was collected and cleaned with a cyclone and filter, and then a compressor was used to increase the pressure above the internal shaft pressure. Three ceramic burners were installed at the three upper shaft tuyeres, which were located 1.45 m below the burden level and 0.55 m below the upper probe level, to raise the temperature. The resultant combusted hot top gas (HTG) was injected into these tuyeres (Table 1) in order to avoid the degradation of sinter by shortening the residence time for sinter in the low-temperature range. The pressurized and cleaned top gas was mixed with synthetic air (20 % oxygen) before combustion. The combusted top gas temperature was controlled at 800 °C by the addition of cold top gas before injection.

The upper shaft tuyeres, lower shaft tuyeres, and blast tuyeres were all vertically aligned.

Operational Conditions of the Raw Materials

A mixed burden of 70 % sinter and 30 % acid pellets was used during the campaign. In order to adjust the final slag basicity, a small amount of lump quartzite was added to the burden. The sinter was transported and screened into sizes larger than 4 mm but less than 40 mm before charging into the storage bins. Sinter quality was generally stable.

Examples of the chemical compositions of sinter, pellets, and injection coal are shown in Table 2. The olivine pellets were used during the start-up week, and the acid pellets were used as part of the mixed sinter and pellet burden. The pellets were standard LKAB products produced in the pellet plant in Kiruna, Sweden.

Both the sinter and pellets were transported in bags or in covered trucks and were held inside a storage facility to avoid an increase in their moisture content due to rain or snowfall. During the whole test operation, the sinter and pellets were sampled every day and analyzed for moisture content and particle size distribution.

Coke and pulverized injection coal used were produced at the SSAB plant in Luleå. The chemical composition of PC is shown in Table 2. The size of the coke was 15–30 mm.

Results and Discussions

General Results

As already explained, the hydrogen reduction trial was executed using LKAB’s EBF [2] to investigate and evaluate the potential for replacing coke and coal as reducing agents in the blast furnace with a H2-rich gas such as COG or RCOG. The test operation started on 16 April 2012 and finished on 11 May 2012. Hot metal production was almost constant throughout the trial. PC consumption was 128 kg/t-hm. The first 7 days of the trial was the start-up period and pellets were used because LKAB uses pellets as the standard ferrous material. Then, the operation was switched to a five-day reference period using 70 % sinter (Japanese standards) and 30 % pellets. The burden distribution was controlled to maintain the hot metal temperature of the reference period. After conditions were stabilized, COG injection from the blast tuyeres started on 28 April. The injection rate was 100 Nm3/t-hm (150 Nm3/h). Oxygen enrichment was adjusted to maintain a constant flame temperature. The PC rate decreased as COG injection increased during the first stage, and then the coke rate decreased. Soot was observed in the dust collected from the furnace top just after COG injection commenced. Pre-heated RCOG injection commenced on 6 May. The injection rate was 150 Nm3/t-hm (225 Nm3/h). HTG was injected from the upper shaft tuyeres during both the COG and RCOG injection period in order to avoid sinter degradation. The injection rate was 100 Nm3/t-hm (150 Nm3/h) in each case (Fig. 4).

Mass Balance of EBF Operations

Table 3 shows the operational data for the reference period, COG injection period, and RCOG injection (150 Nm3/t-hm) period. Although EBF operations showed some fluctuation because of the relatively short time schedule, 1-min data points representing stable operations were selected and averaged over 24 h for each period. Tapping or burden data were adjusted with time shifting. The sum of the coke and PC rates decreased in both the COG and RCOG injection periods. CO gas utilization efficiency (η CO) decreased in both the COG and RCOG injection periods. H2 gas utilization efficiency \( (\eta_{\text{H}_{2}})\) increased in the COG injection period, while it decreased in the RCOG injection period.

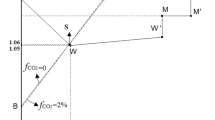

The mass balance between the input and output terms was calculated. Shaft efficiency and heat losses were adjusted to match the operational results using the RIST model [10], and the carbon direct reduction and CO indirect reduction balance were calculated. The authors used a modified RIST model for the purpose of mass and heat balance calculations for the EBF operations with shaft gas injection. The process zone was divided into two regions: an RCOG flow region and a no RCOG region. A mass and heat balance calculation was done for each region, and the results were integrated. The applicable ratio of the two regions was calculated from the RCOG penetration depth data [5]. As described later, the injected RCOG did not penetrate into the center region of the EBF and only flowed near the wall above the shaft tuyere (Fig. 9). The measured penetration depth almost coincided with the calculated value. The calculated penetration depth was derived from the assumption that the ratio of the penetration region to the non-penetration region was proportional to the ratio of the RCOG injection rate to the bosh gas rate.

Figure 5 shows some examples of heat balance for the EBF operation. Each case shows no additional heat loss, and there are no clear differences between the heat balances of the two cases.

Figure 6 shows hydrogen balance during the EBF operation. The residual hydrogen ratio averages about 60–65 %. However, tuyere COG injection shows a better (lower) residual ratio at the furnace top than the RCOG injection into the lower shaft.

Figure 7 shows the change in the degree of reduction of iron in each of the cases. Compared with the reference period, H2 reduction increased, while C direct reduction and CO reduction decreased in both the injection periods. The increase in H2 reduction is considered to be due to the fast reaction rate of the H2 reduction as well as its higher concentration in the gas stream. H2 reduction thus partially replaces C direct reduction and CO reduction. As C direct reduction is a highly endothermic reaction, the decrease in this reaction is the main reason why hydrogen can reduce the input of C and output of CO2, i.e., the decreased coke and PC rates (see Table 3).

Comparison of the degree of reduction achieved in the hydrogen reduction trial [5]

Using both the trial results (experimental) and mathematical calculations [11], it was confirmed that the carbon consumption rates were decreased by about 3 % in comparison with the reference case through either COG blast tuyere injection or RCOG shaft injection, as shown in Fig. 8. In other words, for the reduction of CO2 emissions from the EBF, simultaneous injection of COG and RCOG might not result in further CO2 reduction because the effect of COG and RCOG were almost the same in this trial. Further increasing the injection rates may decrease CO2 emissions from the blast furnaces more. However, it will likely be very difficult to further increase the injection rates because the injection rates used in the trial were almost at maximum considering the COG generation rate in a steelworks plant. Therefore, it will be necessary to develop additional technologies that will increase the reaction efficiency of CO and H2 reduction and reduce CO2 emissions from blast furnaces as part of the future work. The effect of COG and RCOG injections in large blast furnaces will also be investigated by numerical simulations based on the results obtained in this trial.

Comparison of the carbon consumption rates during the EBF trial [11]

Distribution of the Injected Gas

The radial distributions of H2 concentrations measured by the upper shaft probes are shown in Fig. 9. In this figure, COG or RCOG was injected from the left side. During the reference and COG injection periods, the H2 concentrations at the center were the highest, while they were lowest near the furnace wall. The H2 concentration distribution in the COG injection period was uniformly higher than that in the reference period. On the other hand, the H2 concentration was high only near the shaft tuyere during the RCOG injection period.

The vertical distribution of the degree of reduction of the sinter collected from the shaft after completion of operations is shown in Fig. 10. The degree of reduction of the pellets in the reference operation, i.e., no COG or RCOG injection, is also plotted. The degree of reduction for RCOG injection into the lower shaft is clearly higher than in the reference case, especially around the RCOG injection level. The ferrous burden already reduced in the shaft continues to show the advantage of the early reduction as it descends toward the tuyere. Unfortunately, similar data for the COG injection case are not available as the furnace was not dissected after the COG injection period.

Vertical distribution of the degree of sinter reduction [5]

Figure 11 shows a comparison of the oxygen potential (partial pressure) estimated from gas sampling data at each of the gas sampling positions. The H2O concentration was calculated by mass balance because of the difficulty of direct measurement. The oxygen potential was estimated using the CO and CO2 and H2 and H2O partial pressures and thermochemical data, assuming equilibrium. The reference case (conventional blast furnace operation) and the COG tuyere injection case show good correlation between the H2/H2O and CO/CO2 reactions, implying that both are close to equilibrium. On the contrary, in the RCOG shaft injection case, the estimated oxygen potential from the H2/H2O ratio is higher than the estimated oxygen potential from the CO/CO2 reaction. This finding has almost certainly been influenced by the high reduction rate of the hydrogen reaction, which causes a relatively higher oxygen potential than that calculated from the carbon reaction.

Conclusions

Operating trials were conducted in an EBF with the injection of a gas containing a high concentration of H2, such as COG and RCOG. The input of C and output of CO2 decreased by about 3 % in both the COG and RCOG injection periods compared with the reference period for normal operations.

Further increasing the injection rates may decrease CO2 emissions from blast furnaces more. However, it will be likely very difficult to further increase the injection rates because the injection rates used in this trial were almost at maximum considering the COG generation rate in a steelworks. We will develop additional technologies that will increase the reaction efficiency of CO and H2 reductions to reduce CO2 emissions from blast furnaces as part of the future work.

The COURSE50 project aims at developing new drastic CO2 reduction technologies. The target for CO2 emission reduction is approximately 30 % in the steelworks. The project seeks to achieve this reduction through iron ore reduction using hydrogen-amplified COG to suppress CO2 emissions from blast furnaces as well as the separation and recovery of CO2 from BFG using unused exhaust heat from the steelworks. The project has completed the fundamental R&D project in Step 1 (2008–2012) according to schedule, and it is now promoting the integrated R&D project in Step 2 (2013–2017).

The goal of the project is to commercialize the first unit by around 2030 and generalize the technologies by 2050 considering the timing for the replacement of blast furnace equipment.

References

Miwa T, Okuda H (2010) CO2 ultimate reduction in steelmaking process by innovative technology for cool earth 50(COURSE50). J. Jpn. Inst Energ. 89:28–35

Miwa T, Kurihara K (2011) Recent developments in iron-making technologies in Japan. Steel Res Int 82:466–472

Higuchi K, Matsuzaki S, Shinotake A, Saito K (2011) On the reduction of sinter with injecting reformed COG into blast furnace shaft. CAMP-ISIJ 24:186

Higuchi K, Matsuzaki S, Shinotake A, Saito K (2012) Reduction of sinter with injecting reformed or raw COG from tuyere. CAMP-ISIJ 25:886

Watakabe S, Miyagawa K, Matsuzaki S, Inada T, Tomita Y, Saito K, Osame M, Sikström P, Ökvist LS, Wikstrom J (2013) Operation trial of hydrogenous gas injection of COURSE50 project at an experimental blast furnace. ISIJ Int 53:2065–2071

Watakabe S (2013) Current progress on COURSE50 project—recent results on H2 reduction including LKAB EBF’s experiments and CO2 capture. IEAGHG/IETS Iron and Steel Industry CCUS and Process Integration workshop, Tokyo

Dahlstedt A, Hallin M, Tottie M (1999) Lkab’s experimental blast furnace for evaluation of iron ore products. In Proceedings of Scanmet1, vol 1, MEFOS, Sweden, pp 235–245

Zuo G, Hirsch A (2009) The trial of the top gas recycling blast furnace at LKAB’s EBF and scale-up. Rev Metall 106(09):387–392

Van Der Stel J, Sert D, Hirsch A, Eklund N, Sundqvist L (2012) Top gas recycle blast furnace developments for low CO2 ironmaking. In: Proceedings of the 4th international conference on process development in iron and steelmaking (Scanmet IV), vol 1, MEFOS, Lulea, pp 51–60

Rist A, Bonnivard B (1963) Reducing a bed of iron oxide by a gas. Rev Metall 60:23

Ueno H, Endo S, Tomomura S, Ishiwata N (2015) Outline of CO2 ultimate reduction in steelmaking process by innovative technology for cool earth 50 (COURSE50 project). J Jpn Inst Energy 94:1277–1283

Acknowledgments

This study has been carried out as a national contract research project “Development of technologies for environmentally harmonized steelmaking process, ‘COURSE50’” by the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO). The authors are grateful to NEDO for their assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The contributing editor for this article was Sharif Jahanshahi.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nishioka, K., Ujisawa, Y., Tonomura, S. et al. Sustainable Aspects of CO2 Ultimate Reduction in the Steelmaking Process (COURSE50 Project), Part 1: Hydrogen Reduction in the Blast Furnace. J. Sustain. Metall. 2, 200–208 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40831-016-0061-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40831-016-0061-9