Abstract

Introduction

Data assessing longer-term real-world effectiveness and treatment patterns with upadacitinib (UPA), a Janus kinase inhibitor, in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are lacking. We assessed improvement in clinical and patient-reported outcomes and treatment patterns for up to 12 months among adult patients with RA initiating UPA.

Methods

Data were collected from the CorEvitas® RA Registry (08/2019–04/2022). Eligible patients had moderate to severe RA (Clinical Disease Activity Index [CDAI] > 10) and follow-up visits at 6 or 12 months after UPA initiation. Outcomes were mean change from baseline, percentage achieving minimal clinically important differences (MCID) in clinical and patient-reported outcomes, and disease activity at follow-up. We evaluated clinical outcomes and therapy changes among patients with tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) experience and among those receiving UPA as first-line therapy, as well as those receiving UPA as monotherapy versus as part of combination therapy. We further evaluated whether outcomes were similar among those that remained on therapy.

Results

Patients treated with UPA (6-month cohort, N = 469; 12-month cohort, N = 263) had statistically significant improvements (p < 0.001) in mean CDAI, tender/swollen joint counts, pain, and fatigue at follow-up. At 12 months, 46.0% achieved MCID in CDAI and 40.0% achieved low disease activity/remission. Overall, 43.0% discontinued UPA at 12 months; of those receiving combination treatment (N = 90) with conventional therapies and UPA, 42.2% (N = 38) discontinued conventional therapy. Findings were similar in the 6-month cohort and among subgroups. Changes from baseline and proportions of patients achieving MCID or clinical outcomes tended to be numerically lower among patients with TNFi experience and numerically higher among those receiving UPA as first-line therapy.

Conclusions

UPA initiation was associated with improvements in clinical and patient-reported outcomes, with meaningful clinical improvements regardless of prior TNFi experience, line of therapy, or concomitant use of conventional therapies. Further research is needed to better understand sustained response of UPA over longer treatment periods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? | |

Upadacitinib is a recently approved treatment for patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis. Data regarding real-world effectiveness of and treatment patterns with upadacitinib are lacking. | |

This study sought to determine clinical and patient-reported outcomes among patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving upadacitinib treatment. We also studied the subgroups of prior tumor necrosis factor inhibitor users, and upadacitinib initiators that remained on therapy, stratified by upadacitinib line of therapy, to assess upadacitinib-related outcomes in a diverse population. | |

What was learned from this study? | |

This study showed that patients receiving upadacitinib treatment had clinically meaningful improvements in disease activity and patient-reported outcomes over 12 months, with many being able to discontinue concurrent therapies. | |

This study demonstrated the benefits of upadacitinib for the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, regardless of prior treatment history. Overall, patients who received earlier-line upadacitinib therapy had greater clinical improvements. |

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by joint pain, swelling, and stiffness that may result in structural damage and severe disability if left untreated [1, 2]. Several treatment options are now available for patients with RA who have an inadequate response to conventional therapies (conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs [cDMARDs], such as methotrexate), including tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin (IL), and, most recently, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors [1, 3,4,5]. Treatment guidelines for RA recommend addition of a biologic DMARD (bDMARD) in patients who do not achieve treatment targets with the first csDMARD strategy [3, 4].

Approximately 60–90% of patients receive a TNF inhibitor (TNFi) as a first-line biologic bDMARD [6,7,8]. However, up to 70% of patients do not have an adequate clinical response to their first-line therapy and more than half fail to reach treatment targets at 6 months [6, 9]. Moreover, one study showed many patients with RA continued to have symptoms and to be dissatisfied with their treatment, despite having received their current DMARD treatment for at least 1 year [10].

Upadacitinib (UPA), an oral JAK inhibitor (JAKi), is the most recently approved advanced therapy for RA and is indicated for the treatment of patients with moderate to severe RA who had an inadequate response or intolerance to one or more TNFi (USA) or one or more DMARDs (European Union) [11,12,13]. Studies in patients with moderate to severe RA who had inadequate responses or intolerance to either cDMARDs or bDMARDs demonstrated that use of UPA, alone or in combination with methotrexate, resulted in greater improvements in disease activity measures (e.g., American College of Rheumatology [ACR] 20/50/70 and Disease Activity Score 28 with C-reactive protein [DAS28-CRP]) and patient-reported outcomes as compared to patients treated with placebo [14,15,16]. In head-to-head trials, UPA demonstrated greater improvements in DAS28-CRP and higher rates of remission at 12 weeks compared to both adalimumab and abatacept, a T cell co-stimulation modulator [16, 17].

Given the recent approval, it remains unknown whether benefits of UPA are observed and persist over a longer-term follow-up in real-world settings. Moreover, subsequent treatment patterns after initiating UPA have not been systematically examined. Thus, this study aimed to describe the patient characteristics, treatment patterns, and clinical and patient-reported outcomes at 6 and 12 months among patients with moderate to severe RA initiating UPA in real-world clinical practice.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This prospective, observational study examined data on patients with RA from the CorEvitas® RA Registry (Waltham, MA) that has collected patient data from more than 900 rheumatologists across the USA since registry inception in 2001. Data from patients and their providers are collected via questionnaire during routine clinical visits that occur roughly every 6 months. Information on sociodemographics, lifestyle factors, clinical characteristics, disease activity measures, patient-reported outcomes, and RA treatment details (including prior and current therapy, drug start and stop dates, and associated reasons) is gathered during all CorEvitas visits. This study analyzed data collected from August 2019 (US Food and Drug Administration [FDA] approval of UPA for patients with RA [11]) through April 30, 2022. To be eligible for the CorEvitas registry, patients were aged ≥ 18 years and were diagnosed with RA by a participating rheumatologist. Patients unable or unwilling to provide informed consent and those currently participating or planning to participate in a double-blind, randomized clinical trial of an RA drug were excluded. Inclusion of patients with concurrent participation in another observational registry or an open-label phase 3b/4 trial was permitted.

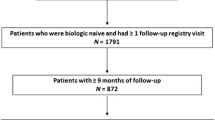

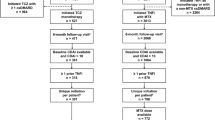

The current analysis included of patients enrolled in the CorEvitas registry who had moderate to severe RA (defined as Clinical Disease Activity Index [CDAI] > 10), were initiating UPA treatment at or after registry enrollment (between August 2019–April 2022), and who had recorded a follow-up registry visit at 6 and/or 12 months after UPA initiation with nonmissing CDAI. To accommodate the variation in clinical practice patterns, patients with recorded follow-up visits occurring within 3 months of the 6- or 12-month timepoints were included; in the event that a patient had multiple follow-up visits, the visit closest to the 6- or 12-month timepoint was used for the analysis. Availability of a 6-month visit with valid outcomes was not required for patient inclusion in the 12-month cohort; likewise, patients in the 6-month cohort were not required to have a 12-month visit with valid outcomes. Patients were further evaluated in two subgroups—those with ≥ 3 months prior TNFi experience and those that used UPA as the first-line therapy. We also explored whether results were similar for patients that continued UPA for the entire follow-up period and explored whether results were similar for those in whom UPA was used as monotherapy or as part of combination therapy (Supplementary Tables 1–3).

Ethical Statement

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practice (GPP). All participating investigators were required to obtain full board approval for conducting noninterventional research involving human subjects with a limited dataset. Sponsor approval and continuing review was obtained through a central institutional review board (IRB), the New England Independent Review Board (NEIRB; no. 120160610). For academic investigative sites that did not receive authorization to use the central IRB, full board approval was obtained from their respective governing IRBs, and documentation of approval was submitted to CorEvitas, LLC before the site’s participation and initiation of any study procedures. All patients in the registry were required to provide written informed consent and authorization before participating. Note: Each registry has its own number. For example, the PsO registry uses (IntegReview, Protocol number is Corrona-PSO-500).

Outcomes

Patients were included in two separate, non-mutually exclusive groups for analysis based on the availability of a follow-up registry visit with valid outcomes at 6 and 12 months (i.e., 6- and 12-month cohorts). Outcomes assessed among all eligible UPA initiators at 6 and 12 months included mean change from baseline, as well as the rates of achieving minimal clinically important differences (MCID) from baseline to 6 or 12 months, in clinical and patient-reported outcomes.

Clinical measures included CDAI, tender and swollen joint counts (28 joint count), and Physician’s Global Assessment of Disease Activity (PGA, by 0–100 visual analog scale [VAS]). The proportion of patients achieving MCID in CDAI was determined on the basis of baseline CDAI score and change from baseline; a reduction in CDAI score indicates improvement. Thus, a patient was considered to have achieved the MCID if there was an improvement > 1 point for those with a baseline CDAI ≤ 10; > 6 points for those with a baseline CDAI > 10 and ≤ 22; or > 12 points for those with a baseline CDAI > 22 [18, 19].

Patient-reported outcomes included Patient’s Global Assessment of Disease Activity (PtGA; 0–100 VAS), Health Assessment Questionnaire–Disability Index (HAQ-DI; range: 0–3), pain (0–100 VAS), and fatigue (0–100 VAS). The MCID for HAQ-DI was defined as a ≥ 0.22-point decrease from baseline [20]. Much better improvement in pain, defined as a reduction of ≥ 20 points on the VAS scale and a ≥ 33% reduction in scores from baseline, was also assessed [21]. In this analysis, MCID thresholds for pain and fatigue were set as a ≥ 10-point improvement from baseline [22, 23].

The proportion of patients in each CDAI disease activity category at the 6- and 12-month follow-up was also reported; high disease activity (HDA; CDAI > 22), moderate disease activity (MDA; 10 < CDAI ≤ 22), low disease activity (LDA; 2.8 < CDAI ≤ 10), or remission (0 < CDAI ≤ 2.8) [18]. This analysis categorized patients by CDAI scores; thus, we present results for remission and LDA individually. The proportion of patients discontinuing UPA therapy up to 6 and 12 months was also evaluated, including reasons for discontinuation.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for each cohort are reported descriptively, with continuous variables reported as means and standard deviations (SD), and categorical variables reported as counts and percentages. The summaries are reported for all UPA initiators, those with ≥ 3 months prior use of TNFi therapy (i.e., TNF-experienced group) and among those initiating UPA as a first-line therapy (i.e., first-line therapy group). For each of these three groups, results are further reported for those patients remaining on UPA at the time of follow-up. Nonresponder imputation was used to account for patients who discontinued UPA prior to the follow-up visit for dichotomous outcomes, and values at or immediately prior to the time of discontinuation were used for continuous variables. One-sample one-sided t tests were used to compare mean changes from baseline to follow-up. The Clopper-Pearson method was used to evaluate response rates at follow-up (with 95% confidence intervals [CI]) [24]. The p values and the 95% CI are only used to evaluate the change either overall or within each level of line of therapy, and monotherapy/combination therapy. Tests were not performed across levels of line of therapy or concomitant therapies. In this study, a p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 469 patients were included in the 6-month cohort, of which 18.6% (N = 87) were initiating first-line UPA and 43.7% (N = 205) had ≥ 3 months prior TNFi experience (Supplementary Table 1); 41 patients in this cohort were initiating UPA as a second or higher line of therapy and were TNFi naïve (data not shown). The 12-month cohort included 263 patients of which 51 initiated UPA as first-line therapy (19.4%) and 187 (71.1%; 1 prior TNFi: N = 65; ≥ 2 prior TNFi: N = 122) had any prior TNFi experience (Table 1); 115 patients (43.7%) had ≥ 3 months experience with a TNFi and 25 patients were both TNFi naïve and initiating UPA as a second or higher line of therapy. The majority of patients (76%) included in the 12-month cohort were also included in the 6-month cohort. Characteristics were generally similar among the 6- and 12-month cohorts; for brevity, we have described the characteristics of the 12-month cohort. The mean age was approximately 60 years and mean disease duration was 11.6 ± 10.5 years overall. Overall, 43.7% (N = 115) were initiating UPA as a fourth or higher line of therapy. Patients with ≥ 3 months prior TNFi experience (N = 115) tended to have longer disease duration than those initiating UPA as a first-line therapy (N = 51; 13.7 ± 9.9 vs 5.3 ± 8.4 years). Among all UPA initiators, 96.2% had received ≥ 1 prior cDMARD, 42.6% had previously received a non-TNFi therapy, and 41.5% had previously received a JAKi. Overall, 55.1% and 44.9% of patients were initiating UPA with moderate and severe disease activity, respectively; the mean baseline CDAI score was approximately 24.1 ± 11.6. Demographic and clinical characteristics among subgroups (i.e., patients with ≥ 3 months TNFi experience and those initiating first-line UPA therapy) were similar to the overall cohort. However, a higher proportion of patients initiating UPA as a first-line therapy had severe disease activity at initiation compared with the overall and TNFi-experienced groups (51.0% vs 44.9% and 43.5%, respectively).

Change from Baseline in Clinical and Patient-Reported Outcomes

Among all UPA initiators, statistically significant improvements in both clinical and patient-reported outcomes were observed at 6 months after UPA initiation (Table 2). The mean improvement in CDAI (range 0–76), tender and swollen joint counts (range 0–28), and patient reported pain (range 0–100) was 8.3 ± 12.9, 3.6 ± 6.8, 2.4 ± 4.8, and 11.9 ± 25.3 points, respectively. Outcomes among the 12-month cohort showed similar patterns and tended to be numerically greater (Table 3).

Similar changes from baseline in clinical and patient-reported outcomes were observed among all subgroups for both the 6- and 12-month cohorts; however, patients receiving first-line UPA therapy had numerically greater changes from baseline in all outcomes compared to other subgroups (Tables 2 and 3). In contrast, while all improvements from baseline were statistically significant, patients with TNFi experience who initiated UPA had numerically smaller changes from baseline compared to other subgroups. Among both TNFi-experienced and first-line UPA initiators, those remaining on UPA therapy at the time of follow-up had numerically greater improvements from baseline compared to the all UPA initiators cohort. Improvements at 6 and 12 months were similar among those receiving UPA monotherapy compared to those receiving combination therapy, as well as those receiving steroid treatment versus not at the time of follow-up (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

Response Rates in Clinical and Patient-Reported Outcomes

Among all UPA initiators, 42.0% achieved MCID in CDAI at 6 months post-UPA initiation (Fig. 1a). Similarly, 45.0% achieved MCID in patient-reported pain, 42.0% achieved MCID in patient-reported fatigue, and approximately one-third achieved MCID in HAQ-DI (34.0%) or “much better improvement” in pain (29.0%). Numerically greater results were observed among patients in the 12-month cohort (Fig. 1b). Patients with TNFi experience also demonstrated significant improvements in all outcomes, though at somewhat lower rates than observed for first-line UPA initiators. Among both the 6- and 12-month cohorts, patients who remained on UPA at follow-up had higher rates of clinical improvement across all measures than the all UPA initiators cohort. Rates of clinical improvement were similar among patients receiving UPA monotherapy versus combination therapy at both 6 and 12 months (Supplementary Table 4).

Rates of achieving minimum clinically important differencesa in clinical and patient-reported outcomes at a 6-month and b 12-month follow-up. aMCID for CDAI was based on baseline CDAI score. For baseline CDAI > 10 and ≤ 22, MCID = > 6-point decrease; and baseline CDAI > 22, MCID = > 12-point decrease. MCID for HAQ-DI was ≥ 0.22-point decrease. For assessments measured on a 100-point VAS scale, MCID was set at ≥ 10-point decrease. “Much Better Improvement” in patient-reported pain was defined as a 20-point decrease and a ≥ 33% decrease in scores from initiation (Salaffi F, et al. Eur J Pain. 2004;8(4):283–91). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals of the mean response rate. CDAI Clinical Disease Activity Index, HAQ-DI Health Assessment Questionnaire – Disability Index, MCID minimal clinically important difference, TNFi tumor necrosis factor inhibitor, VAS visual analog scale, UPA upadacitinib

At the 6-month follow-up, 8.1% and 29.0% of all UPA initiators achieved remission (CDAI ≤ 2.8) or LDA (2.8 < CDAI ≤ 10), respectively (Fig. 2a). Patients with TNFi experience had numerically lower rates of remission or LDA (3.4% and 28.3%, respectively) while rates of remission or LDA were higher among first-line initiators (18.4% and 25.3%, respectively). Compared to the 6-month cohort, rates of remission and LDA in the 12-month cohort were numerically greater among all UPA initiators and subgroups (all UPA initiators, 11.1% and 29.1%, respectively; TNFi-experienced initiators, 5.2% and 29.6%, respectively; first-line initiators, 16.0% and 28.0%, respectively; Fig. 2b).

Treatment Patterns Among All UPA Initiators

Among the 6-month cohort, 31.8%, 35.6%, and 23.0% had discontinued therapy at follow-up for all UPA initiators, TNFi-experienced UPA initiators, and first-line UPA initiators, respectively (Table 4). Rates of discontinuation at 12 months were similar among the overall, TNFi-experienced, and first-line UPA initiators groups (43.0% vs 45.2% vs 41.2%, respectively; Table 4). Among all groups in the 6- and 12-month cohorts, the most commonly reported reasons for discontinuation were related to safety and efficacy.

By the 12-month follow-up, among those patients who remained on therapy (N = 150), 11.7% of those initiating UPA as monotherapy (N = 60) had added a cDMARD. Among those who initiated UPA as combination therapy and remained on therapy by 12 months (N = 90), 42.2% discontinued at least one cDMARD. Among patients with TNFi experience who initiated and remained on UPA, lower proportions of patients had changes to their treatment regimen (i.e., adding or removing cDMARDs). However, at 12 months, a markedly higher proportion of patients who received first-line UPA, and remained on therapy, were able to discontinue a cDMARD from UPA combination therapy than patients in the all UPA initiators and TNFi-experienced groups (66.7% vs 42.2% and 34.4%, respectively).

Discussion

This study is among the first to assess outcomes and treatment patterns among a broad range of patients with moderate to severe RA initiating UPA therapy in real-world practice. Overall, patients initiating UPA showed meaningful improvements in clinical and patient-reported outcomes at 6 and 12 months post-UPA initiation. Indeed, in all subgroups studied at 6 and 12 months, achievement of LDA or remission ranged between 31.7% and 44.0%; up to 48.0% of all UPA initiators achieved clinically meaningful improvements in clinical and patient-reported outcomes. A substantial proportion of patients who initiated UPA as combination therapy with cDMARDs were able to discontinue at least one cDMARD by 12 months (i.e., 24.2% of all combination therapy initiators and 42.2% of combination therapy initiators who remained on UPA at 12 months). Overall, findings were generally similar among patients with prior TNFi experience and patients initiating UPA as monotherapy or combination therapy; patients initiating UPA as a first-line therapy generally demonstrated better outcomes. The benefit observed in the TNFi-experienced cohort and among those with the use of many prior therapies is important because it highlights the value of UPA in patients with difficult-to-treat and/or recalcitrant disease.

In August 2019, UPA was approved by the FDA for use in patients with moderate to severe RA with inadequate response or intolerance to methotrexate, and this was later amended to patients with inadequate response or intolerance to ≥ 1 TNFi [11, 12]. Prior phase 3 studies of UPA showed that patients receiving UPA, with or without background cDMARD therapy, had significantly greater improvements in disease severity, symptoms, and physical functioning compared to patients treated with placebo, regardless of prior bDMARD use [14,15,16, 25]. Likewise, UPA also demonstrated greater improvements in clinical and patient-reported outcomes in head-to-head trials with adalimumab [16] in patients with an inadequate response or intolerance to cDMARDs, and with abatacept [17] in patients with an inadequate response or intolerance to bDMARDs. In the SELECT-BEYOND trial, 47% of patients with an inadequate response or intolerance to bDMARDs receiving UPA 15 mg achieved LDA or remission (CDAI ≤ 10) at 24 weeks [14]. Given the high proportion of patients receiving UPA as a later line therapy, overall rates of LDA and remission from this real-world study were expectedly lower (31.7% and 34.8% and 6 and 12 months, respectively) among UPA initiators with TNFi experience. The general changes in tender/swollen joint counts, patient-reported pain, and PtGA and PGA scores observed in the SELECT-BEYOND trial are consistent with those seen in this report, for all UPA initiators and those with prior TNFi experience [14].

Other real-world analyses evaluating the effectiveness of RA therapies are useful to help contextualize the results observed in the present study. A Canadian study assessing real-world effectiveness of TNFi and tofacitinib (TOF), another JAKi, showed that rates of remission/LDA at 6 months were 36.7% and 33.2%, respectively; 67.9% of patients treated with TOF had prior bDMARD experience [26]. In a separate analysis in a Swiss rheumatology registry, 40% of TNFi users, 40% of TOF users, and 46% of those receiving a therapy with a different mechanism of action (i.e., abatacept, tocilizumab, or sarilumab) achieved LDA at 12 months [27]. In the latter study, approximately three-quarters of TOF users had received ≥ 1 bDMARD, which is consistent with UPA users in this study [27]. In our analysis, 40.2% of patients initiating UPA achieved remission/LDA at the 12-month follow-up. Taken together, this demonstrates that rates of remission/LDA with UPA treatment are comparable to those seen in patients receiving TNFi or other JAKi.

This study incorporated data from a broad sample of patients treated with UPA in a real-world setting, including those with a range of prior treatment experience (i.e., UPA use in first line through fourth line and later) and those initiating UPA as monotherapy or combination therapy. While improvements in clinical and patient-reported outcomes were reported across all groups, greater improvements were observed among those receiving UPA as first-line therapy. The findings demonstrating real-world effectiveness of UPA in a TNFi-experienced population may be of greatest relevance to current clinical practice given recent guidelines for use of a bDMARD (e.g., IL-6 inhibitor) or tsDMARD (e.g., JAKi) with another mechanism of action after TNF failure [3, 4]. This remains an important group because up to 70% of patients do not have an adequate clinical response to their first-line therapy and more than half fail to reach treatment targets at 6 months [6, 9]. Among those patients that do not achieve treatment targets and present with poor prognostic factors, the addition of JAKi can be considered so long as providers account for relevant patient characteristics (e.g., cardiovascular event or malignancy risk factors) [3, 4]. Nonetheless, the real-world data from this study suggest that treatment with UPA provides meaningful improvements in clinically relevant outcomes for patients who experienced an inadequate response to a TNFi, supporting data from clinical trials.

Thus, a primary strength of this study is that, in addition to being the first 12-month real-world effectiveness data reported, it includes and evaluates UPA initiators across a number of important subgroups. This may help to provide confidence in real-world UPA prescribing. This study was conducted using a real-world, prospective, observational registry with systematic collection of detailed information on demographics, clinical and patient-reported outcomes, treatment history, and history of comorbidities. As such, there are low rates of missing data within the registry. CorEvitas patients are recruited from rheumatology practices and are thus more representative of the general population of patients with RA, compared to those participating in clinical trials. This study described several disease activity measures and patient-reported outcomes, including many measures not consistently available in other real-world data sources, such as electronic medical records and administrative claims databases.

This study is subject to several limitations. While this population may more accurately reflect the real world than those included in clinical trials, there are some caveats. Providers volunteer to participate in the CorEvitas RA Registry, and selected patients must also agree to participate. This may limit the generalizability of the findings to the patient with RA population at large. Likewise, this analysis used data on a US population of patients with RA and thus may not be generalizable to other countries which may have different disease management practices. Sample size was limited in some subgroup analyses, resulting in less precise estimates. To maintain larger sample sizes, two separate, non-continuous cohorts (i.e., 6- or 12-month) were analyzed. As such, it is difficult to compare changes observed at 6 months with those observed at 12 months since the patient populations are distinct. However, that there was significant patient overlap in the two cohorts, wherein 76% (201/263) of patients in the 12-month cohort analysis were also included in the 6-month cohort analysis and there were no notable differences in the two cohorts at baseline. Likewise, follow-up rheumatologist visits were considered valid for analysis purposes even if not occurring precisely at the 6-month and 12-month follow-up timepoints (i.e., ± 3 months) to allow for the significant variation that may occur in real-world clinical practice patterns. In addition, a high proportion of patients did not report reasons for discontinuing UPA; thus, the data reported here may not fully reflect why patients and/or physicians chose to discontinue UPA treatment. In addition, descriptive data for those who continued UPA therapy at 6 and 12 months should be interpreted with caution because this group does not include those who discontinued the therapy as a result of poor health or lack of disease improvement. By study design, this analysis assessed real-world effectiveness and treatment patterns among patients initiating UPA and was not adequately designed to assess safety; however, a long-term safety assessment is currently ongoing within the CorEvitas registry, and such data is forthcoming. Finally, multiple tests were conducted for the outcomes evaluated in this analysis and some of the outcomes are likely correlated. The p values reported should be considered exploratory and should be interpreted in the context of multiple comparisons.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated significant and clinically meaningful improvement in disease activity and patient-reported outcomes in patients with RA initiating UPA therapy, regardless of line of therapy, or use of UPA as monotherapy or combination therapy. Moreover, a substantial number of patients who were able to remain on therapy throughout the 12-month follow-up were able to reduce their medication burden by reducing concurrent cDMARD treatment. Further research is needed to better understand clinical outcomes and treatment patterns among patients treated with UPA for greater than 12 months.

Data Availability

Data are available from CorEvitas, LLC through a commercial subscription agreement and are not publicly available. No additional data are available from the authors.

References

Coates LC, FitzGerald O, Helliwell PS, Paul C. Psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis: is all inflammation the same? Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46(3):291–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.05.012.

Geijer M, Alenius GM, Andre L, et al. Health-related quality of life in early psoriatic arthritis compared with early rheumatoid arthritis and a general population. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2021;51(1):246–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.10.010.

Fraenkel L, Bathon JM, England BR, et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73(7):1108–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.41752.

Smolen JS, Landewe RBM, Bergstra SA, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2022 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82(1):3–18. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard-2022-223356.

Lin YJ, Anzaghe M, Schulke S. Update on the pathomechanism, diagnosis, and treatment options for rheumatoid arthritis. Cells. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9040880.

Bergman MJ, Kivitz AJ, Pappas DA, et al. Clinical utility and cost savings in predicting inadequate response to Anti-TNF therapies in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Ther. 2020;7(4):775–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-020-00226-3.

Ertenli AI, Kalyoncu U, Karadag O, et al. Trends in the choice of first biologic and targeted synthetic DMARD in rheumatoid arthritis patients: 20-years journey of HURBIO real-life registry [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:1124.

Aaltonen KJ, Ylikyla S, TuulikkiJoensuu J, et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of tumour necrosis factor inhibitors in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in randomized controlled trials and routine clinical practice. Rheumatol (Oxf). 2017;56(5):725–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kew467.

Arnell C, Bergman M, Basu D, et al. Guided therapy selection in rheumatoid arthritis using a molecular signature response classifier: an assessment of budget impact and clinical utility. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2021;27(12):1734–42. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2021.21120.

Radawski C, Genovese MC, Hauber B, et al. Patient perceptions of unmet medical need in rheumatoid arthritis: a cross-sectional survey in the USA. Rheumatol Ther. 2019;6(3):461–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-019-00168-5.

AbbVie Receives FDA Approval of RINVOQ™ (upadacitinib), an oral JAK inhibitor for the treatment of moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis [press release]. AbbVie, Inc., 16 August 2019. 2019.

AbbVie Inc. Rinvoq® Prescribing Information. Updated May 2023.

AbbVie receives European Commission approval of RINVOQ™ (upadacitinib) for the treatment of adults with moderate to severe active rheumatoid arthritis [press release]. December 18, 2019. 2019.

Genovese MC, Fleischmann R, Combe B, et al. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis refractory to biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (SELECT-BEYOND): a double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10139):2513–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31116-4.

Burmester GR, Kremer JM, Van den Bosch F, et al. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response to conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (SELECT-NEXT): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10139):2503–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31115-2.

Fleischmann R, Pangan AL, Song IH, et al. Upadacitinib versus placebo or adalimumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate: results of a phase III, double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(11):1788–800. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.41032.

Rubbert-Roth A, Enejosa J, Pangan AL, et al. Trial of upadacitinib or abatacept in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(16):1511–21. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2008250.

Curtis JR, Chen L, Danila MI, et al. Routine use of quantitative disease activity measurements among US rheumatologists: implications for treat-to-target management strategies in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2018;45(1):40–4. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.170548.

Pappas DA, Tundia N, Shan Y, Litman HJ, Kremer J. Unmet treat-to-target goals with available targeted immunomodulators in the management of rheumatoid arthritis: real world evidence from the Corrona registry [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 9).

Mease P, Strand V, Gladman D. Functional impairment measurement in psoriatic arthritis: importance and challenges. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018;48(3):436–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.05.010.

Salaffi F, Stancati A, Silvestri CA, Ciapetti A, Grassi W. Minimal clinically important changes in chronic musculoskeletal pain intensity measured on a numerical rating scale. Eur J Pain. 2004;8(4):283–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2003.09.004.

Strand V, Boers M, Idzerda L, et al. It's good to feel better but it's better to feel good and even better to feel good as soon as possible for as long as possible. Response criteria and the importance of change at OMERACT 10. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(8):1720–7. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.110392.

Kitchen H, Hansen BB, Abetz L, Hojbjerre L, Strandberg-Larsen M. Patient-reported outcome measures for rheumatoid arthritis: minimal important differences review. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(Suppl 10):Abstract 2268.

Clopper CJ, Pearson ES. The use of confidence or fiducial limits illustrated in the case of the binomial. Biometrika. 1986;26(5):404–13.

Smolen JS, Pangan AL, Emery P, et al. Upadacitinib as monotherapy in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response to methotrexate (SELECT-MONOTHERAPY): a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019;393(10188):2303–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30419-2.

Movahedi M, Cesta A, Li X, et al. Physician- and patient-reported effectiveness are similar for tofacitinib and TNFi in rheumatoid arthritis: data from a rheumatoid arthritis registry. J Rheumatol. 2022;49(5):447–53. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.211066.

Finckh A, Tellenbach C, Herzog L, et al. Comparative effectiveness of antitumour necrosis factor agents, biologics with an alternative mode of action and tofacitinib in an observational cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Switzerland. RMD Open. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001174.

Acknowledgements

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance.

Medical writing services provided by Samantha D. Francis Stuart, PhD, of Fishawack Facilitate Ltd, part of Avalere Health, and funded by AbbVie. Editorial support was provided by Jillian Conte, BS, of CorEvitas, LLC.

Funding

This study was sponsored by CorEvitas, LLC and the analysis, as well as the Rheumatology and Therapy Rapid Service Fee, was funded by AbbVie. Access to study data was limited to CorEvitas and CorEvitas statisticians completed all the analysis; all authors contributed to the interpretation of the results. CorEvitas has been supported through contracted subscriptions in the last 2 years by AbbVie, Amgen, Inc., Arena, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Chugai, Eli Lilly and Company, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., LEO Pharma, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfizer, Inc., Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Sanofi, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., and UCB S.A. No honoraria or payments were made for authorship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Joshua F. Baker, Patrick Zueger, Mira Ali, Denise Bennett, Miao Yu, Yolanda Munoz Maldonado, and Robert R. McLean made substantial contributions to study conception and design, interpretation of data, and were involved in drafting and critically revising the manuscript for intellectual content. Yolanda Munoz Maldonado and Miao Yu contributed to data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Joshua F. Baker has received consulting fees from CorEvitas and Cumberland Pharma and has received funding from Horizon Pharma. Denise Bennett, Miao Yu, Yolanda Munoz Maldonado, and Robert R. McLean are employees of CorEvitas (previously Corrona, LLC). Mira Ali and Patrick Zueger are employees of AbbVie Inc. and may own stock.

Ethical Approval

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practice (GPP). All participating investigators were required to obtain full board approval for conducting noninterventional research involving human subjects with a limited dataset. Sponsor approval and continuing review was obtained through a central institutional review board (IRB), the New England Independent Review Board (NEIRB; no. 120160610). For academic investigative sites that did not receive authorization to use the central IRB, full board approval was obtained from their respective governing IRBs, and documentation of approval was submitted to CorEvitas, LLC before the site’s participation and initiation of any study procedures. All patients in the registry were required to provide written informed consent and authorization before participating. Note: Each registry has its own number. For example, the PsO registry uses (IntegReview, Protocol number is Corrona-PSO-500).

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baker, J.F., Zueger, P., Ali, M. et al. Real-World Use and Effectiveness Outcomes in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis Treated with Upadacitinib: An Analysis from the CorEvitas Registry. Rheumatol Ther 11, 363–380 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-024-00639-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-024-00639-4