Abstract

Objective

To explore fourth-year medical students’ experience with a virtual, near-peer facilitated pediatric boot camp through the lens of self-determination theory (SDT).

Methods

We developed a virtual pediatric boot camp elective for fourth-year medical students pursuing pediatric residency using Kern’s six steps of curriculum development. The two-week virtual elective consisted of facilitated video conferences and small group discussions led by two senior pediatric residents. Semi-structured focus groups were conducted after elective completion. Using SDT as our conceptual framework, we explored participants’ experience with the near-peer facilitation of the boot camp. Focus group recordings were transcribed and thematically analyzed using deductive coding for SDT, with inductive coding for themes outside the theory’s scope. Saturation was reached after three focus groups. The codebook was iteratively revised through peer debriefing between coders and reviewed by other authors. Credibility was established through member checking.

Results

Ninety-two percent of eligible medical students (n = 23/25) participated in the boot camp with attendance ranging from 18–21 students per session. Twelve students (52%) participated in three focus groups. Qualitative analysis identified five major themes. Four themes consistent with SDT emerged: competence, autonomy, relatedness to near-peers, and relatedness to specialty/institution. The learning environment, including the virtual setting, emerged as an additional, non-SDT-related theme.

Conclusions

Medical students’ experience with our virtual boot camp closely aligned with SDT. Near-peer relatedness emerged as a unique theme which could be further investigated in other aspects of medical student education. Future research could evaluate higher-level learning outcomes from near-peer educational opportunities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, fourth-year medical students missed vital in-person educational opportunities. Educators filled this need with virtual education, including virtual boot camps [1,2,3]. Residency preparatory boot camps supplement undergraduate medical learning, demonstrating improvements in skills, knowledge, and confidence [4]. Pediatric boot camp electives have reported outcomes of increased self-assessed confidence in residency-specific tasks and communication skills [3, 5, 6].

Near-peer facilitation has been implemented in medical student pre-clinical and clinical education. Both learners and teachers have documented benefits including increased test scores [7], increased self-efficacy [8, 9], and improved understanding of material with long-term retention [10]. While pediatric boot camps are not novel, there is little evidence on the impact of near-peer facilitation on these courses. The suspension of in-person residency elective rotations during COVID-19 provided the opportunity for residents to serve as near-peer facilitators and afforded medical students a unique educational opportunity to prepare for residency.

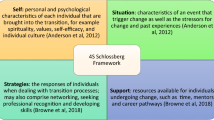

Self-determination theory (SDT) purports that intrinsic motivation is mediated through competence, autonomy, and relatedness, which we anticipated would align with student motivation to participate [11]. Within the theory of SDT, external factors, such as learning environment and teaching style, can catalyze or undermine intrinsic motivation [12]. In this study, we explored students’ experience with near-peer facilitation of a virtual pediatric boot camp through the lens of SDT.

Materials and Methods

Participant Selection

Fourth-year medical students at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine (UCCOM) who already matched into a pediatric or combined-pediatric residency program in the 2020 Residency Match were eligible for study participation. Two students who delayed Match to 2021 were also included. We contacted eligible students via email once to assess interest in participation.

Curriculum Development

We applied Kern’s six-step approach to curriculum development to design and implement the boot camp [13]. Interested students and program directors of UCCOM’s affiliated pediatric residency completed a targeted needs assessment via electronic survey. The 18-question, Likert-scale student survey asked about confidence in diagnosis and management of common pediatric diseases and residency tasks. The 20-question, Likert-scale program director survey focused on clinical knowledge and skills of a typical incoming intern. Content for the survey was guided by the Council on Medical Student Education in Pediatrics (COMSEP) acting internship (AI) objectives, which were felt to represent competencies that graduating medical students should have in pediatrics. Survey items were primarily derived from the sections on “Patient Care,” “Medical Knowledge,” and “Interpersonal and Communication Skills” [14]. In addition, the AI elective director served as a local expert on expected competencies of graduating students.

The goal of the curriculum was to improve the confidence of fourth-year medical students’ medical management of common pediatric problems and ability to complete frequently encountered residency tasks. Course content, based on the results of the surveys, was created and facilitated by two second-year pediatric residents and reviewed by the AI elective director. The course was conducted via ZoomTM and consisted of video conferences, small group discussions in break-out rooms, and role modeling by near-peer facilitators. While the AI elective director reviewed content for accuracy prior to sessions, all sessions were facilitated by the two second-year residents, providing exclusively near-peer facilitation. Most sessions were interactive, with participating students addressing knowledge-check questions and/or completing activities in small groups. The course occurred over 2 weeks in May 2020, with two- to three-hour sessions 5 days per week. The course schedule, including topics, is depicted in Table 1. Broadly, the sessions primarily addressed inpatient and outpatient management of common pediatric pathologies (e.g., bronchiolitis, asthma, hyperbilirubinemia), commonly used therapies (e.g., oxygen, antibiotics, intravenous fluids), documentation, and communication with co-residents, patient families, and other providers.

Study Design and Data Collection

After course completion, students were invited to participate in semi-structured focus groups to explore their experience. We developed a question guide focusing on exploring the impact of near-peer facilitation through the lens of SDT (Supplement). The question guide was reviewed by three physicians with expertise in medical student education and medical education research. Questions were piloted by a resident from an outside residency program for clarity. Focus groups were facilitated by two authors via ZoomTM [15]. The Institutional Review Board approved this study as exempt.

Data Analysis

Focus groups were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed by two authors using deductive coding for SDT, with inductive coding for themes outside the theory’s scope. The authors discussed codes and resolved discrepancies before further transcript review to create a codebook. The codebook was iteratively revised through peer debriefing between coders and reviewed by the other authors. Focus groups were continued until no new codes emerged, reaching saturation. Initial transcripts were re-reviewed once the codebook was finalized. Main themes were identified and discussed with all authors until consensus was reached. Credibility was established through member checking [15].

Results

Ninety-two percent of eligible medical students (n = 23/25) participated in the boot camp, with attendance at each session ranging from 18 to 21 students per session. Twelve boot camp participants (52%) volunteered to participate in one of three focus groups.

Thematic analysis of the focus group transcripts identified five major themes, four of which aligned with SDT, with nineteen associated subthemes. Table 2 depicts themes, subthemes, and representative quotes.

Theme 1: Competence: Desire for Competence in Clinical Decision-Making, Communication, and Resident Tasks

Focus group participants identified competence as a factor in boot camp participation. Subthemes included decompensation and situational awareness, communication, and resident tasks. Participants appreciated “walking through how to go to a room where someone is decompensating or responding to a code.” Participants also valued learning about interdisciplinary and patient/family-physician communication. They desired competence in completing residency skills and tasks such as the technical skills of selecting admission orders and ordering weight-based medications.

Theme 2: Autonomy: Participation Driven by Anxiety Regarding Transition to Residency and Flexibility in Attendance Policy

The theme of autonomy explored why students opted into the course and continued to attend. Subthemes included flexibility with attendance, fear/anxiety as a motivator, and returning to a medical mindset. Participants appreciated that the course, which did not have attendance requirements, allowed students to attend based on their own schedule. A common reason for participating in the boot camp was “fear” or “anxiety,” specifically related to feeling unprepared for residency.

The subtheme “returning to a medical mindset” was specific to the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants identified lack of structure to their days and missed clinical opportunities as motivators to participate in the course. One student reported that, “getting back into the habit of thinking everyday…was definitely a motivating factor.”

Theme 3: Relatedness to Near-Peers: Near-Peer Facilitation and Its Associated Benefits and Challenges on Students’ Learning Experience

We noted two distinct themes pertaining to relatedness: relatedness to near-peers (R-NP) and relatedness to institution/specialty (R-IS). R-NP addressed how near-peer instruction impacted participants’ learning experience. Six subthemes within the R-NP theme included resident-specific knowledge, knowledge perceived as relevant, residents as role models, residents perceived as more honest, residents perceived as less judgmental, and limitations to near-peer instruction.

Participants emphasized many positive aspects of near-peer instruction, suggesting that residents shared knowledge directly relevant to daily resident duties because they are currently engaging in these activities, whereas attendings may not have completed typical resident tasks in years. One student expressed that information felt more relevant because they “could see myself [as a resident] one day,” and near-peers served as role models. Participants felt near-peer facilitators provided realistic advice based on personal experiences, which contributed to participants perceiving near-peer instructors as honest. Near-peer instructors were viewed as less judgmental than attendings, resulting in participants endorsing greater willingness to respond to facilitators’ questions and to ask their own.

Participants acknowledged limitations of near-peer instruction, primarily related to the degree of knowledge and experience of near-peers compared to attendings. Participants reported attendings know “what makes a strong and weak resident” because they have more experience teaching residents. Some noted that they would feel the need to “focus more” had attendings taught the course.

Theme 4: Relatedness to Institution/Specialty: Near-Peer Facilitation Impacted Students' Connection to the Field of Pediatrics and the Institution

The R-IS theme explores how near-peer instruction impacted participants’ relationships to their future residency program, and to pediatrics as a specialty. Participants who matched at their home institution reported having residents as teachers made them feel more connected to the program. Regarding pediatrics as a specialty, one participant reported that the instructors’ personalities “reaffirmed” that pediatrics was right for them.

Theme 5: Learning Environment and Course Structure: Importance of an Interactive, Consistent Learning Environment that Encompassed Non-physician Voices

The final theme, which was not aligned within the SDT framework, encompassed participant perceptions of the learning environment and course structure. Participants described how the course structure impacted their learning experience. Subthemes included efficient, interactive, instructor consistency, non-physician participants, and virtual environment. Participants reported efficiency in the sessions, which addressed each topic in approximately 30 minutes. They appreciated that instructors asked participants questions “and would wait for someone to respond,” which was “key for an interactive learning experience.” Participants expressed that two instructors provided the appropriate balance of speaker variety and consistent teaching style. Participants reported that including non-physician speakers for relevant topics made “it more real than if we had to simulate those conversations.” The virtual course format necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic was not felt to hinder learning, with some preferring virtual to in-person instruction.

Discussion

Our resident-facilitated virtual pediatric boot camp was successfully conducted with consistently high attendance. Focus groups exploring students’ experience with the near-peer facilitation and its impact on intrinsic motivation yielded themes that aligned with the main components of SDT, competence, autonomy, and relatedness [16, 17]. A theme addressing the learning environment was also identified.

Participants sought competence in technical residency skills, and clinical and communication skills, such as identifying and responding to decompensation and interdisciplinary communication. This is consistent with a study of new interns in the United Kingdom who identified decision-making and responding to emergencies as areas of low confidence [18]. While boot camps have previously addressed communication topics with trained facilitators, standardized patients, or student role play [5], our boot camp incorporated non-physicians for specific communication topics, which was favored by participants, who described these encounters as more realistic.

In terms of autonomy, anxiety and fear were the most common motivators for initial and continued participation in the course. While such anxiety is expected during the transition to residency, we suspect this was amplified by the temporary cessation of clinical rotations during the COVID-19 pandemic [19, 20]. The resulting lack of daily structure and clinical learning opportunities also served as motivation for participation.

Two distinct categories of relatedness, R-NP and R-IS, emerged. The former is a novel aspect of relatedness in SDT. Participants compared near-peer teaching with faculty-led instruction, expressing that near-peers were more relatable and shared more relevant knowledge. This observation is consistent with studies in which students reported benefiting from the recent experience of near-peers, while faculty teaching may seem too advanced or not applicable [7, 8, 21]. Our participants also perceived near-peers as less judgmental than faculty, which has been reported in other near-peer teaching experiences [8].

Furthermore, participants voiced that near-peer facilitators enhanced their connection to the pediatric specialty, highlighting relatedness traditionally associated with SDT. For participants who matched at their home institution, learning from future colleagues promoted a connection to the institution prior to beginning residency. Near-peer education during medical students’ transition from pre-clinical years to clinical rotations has previously demonstrated positive learner feedback [9]. The transition from medical school to residency is similarly a unique opportunity for near-peer instruction because of its potential impact on relatedness to institution and specialty.

While residency preparatory boot camps are not novel, we believe our boot camp is the first in pediatrics to utilize a near-peer teaching model. Other published pediatric boot camps have been developed and facilitated only by attending faculty [3, 22, 23], and a recently published toolkit for developing pediatric boot camps does not mention utilizing near-peers as facilitators [24]. Given the reported increased level of engagement that resulted from relatedness to near-peers, we believe that near-peer education may be underutilized in pediatric residency preparatory courses.

Though participants generally supported the use of near-peer facilitators, they noted some limitations, such as the perception that near-peers possess less clinical knowledge than attending physicians. It is unclear if this perception correlates with educational outcomes, as limited studies have looked at higher-level outcomes of near-peer learning. However, one study showed students in a near-peer musculoskeletal curriculum had improved test scores compared to previously published passing rates [21], indicating that near-peer facilitation may be as effective as more traditional, attending-led teaching instruction.

Our study has limitations. We studied a single-specialty preparatory boot camp at one institution, which may limit transferability to other specialties or settings. Selection bias may have impacted our focus group participation, as not all boot camp students participated in focus groups. While the focus group participants appeared engaged in the discussion, the small size of the groups may have caused participants to feel pressure to speak in response to silence. However, larger focus groups were not feasible due to scheduling conflicts. Social acceptability bias may have existed in focus groups because of the relationship between moderators and participants. There is also the potential for recall bias, although focus groups were held 3 days after course completion to minimize this.

Conclusions

The themes identified in our qualitative study align with the key components of SDT: competence, autonomy, and relatedness. Participants desired competence in clinical decision-making, communication, and resident tasks. They described autonomy as a key motivator for participation in the course. Relatedness emerged in two different domains: to near-peer facilitators and to the institution and specialty. While this course was created to fill an educational gap created by COVID-19, the near-peer relational learning could be translated to other formal medical student education. Future research could explore higher-level learning outcomes from near-peer-facilitation and its application in other educational settings.

Availability of Data and Material

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Dr. Elliott, upon reasonable request.

References

Chick RC, et al. Using technology to maintain the education of residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(4):729–32.

Bhashyam AR, Dyer GSM. “Virtual” boot camp: orthopaedic intern education in the time of COVID-19 and beyond. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28(17):e735–43.

Monday LM, et al. Outcomes of an online virtual boot camp to prepare fourth-year medical students for a successful transition to internship. Cureus. 2020;12(6):p.e8558.

Blackmore C, et al. Effects of postgraduate medical education “boot camps” on clinical skills, knowledge, and confidence: a meta-analysis. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(4):643–52.

Burns R, et al. Pediatric boot camp series: obtaining a consult, discussing difficult news. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10437.

Metz J, et al. Pediatric boot camp series: infant with altered mental status and seizure-a case of child abuse. MedEdPORTAL. 2017;13:10552.

Khaw C, Raw L. The outcomes and acceptability of near-peer teaching among medical students in clinical skills. Int J Med Educ. 2016;7:188–94.

de Menezes S, Premnath D. Near-peer education: a novel teaching program. Int J Med Educ. 2016;7:160–7.

Knobloch AC, et al. The impact of near-peer teaching on medical students’ transition to clerkships. Fam Med. 2018;50(1):58–62.

Hall S, et al. The benefits of being a near-peer teacher. Clin Teach. 2018;15(5):403–7.

Deci EL, Ryan RM. Self determination theory. In: Van Lange PAM, Kruglanski AW, Higgins ET, editors. Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd; 2012. p. 416–36.

Ryan RM, Deci EL. intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2000;25(1):54–67.

Thomas PA, et al. Curriculum development for medical education : a six-step approach. Third edition. ed. 2016. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xii, 300 pages.

Konopasek L, Sanguino S, Bostwick S, Hillenbrand K. COMSEP and APPD Pediatric Subinternship Curriculum. 2010. Cited 2020 Available from: https://media.comsep.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/30172802/COMSEP-APPDF.pdf.

Hanson JL, Balmer DF, Giardino AP. Qualitative research methods for medical educators. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11(5):375–86.

Deci EL, Ryan RM. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psych Inquiry. 2000;11(4):227–68.

Ten Cate TJ, Kusurkar RA, Williams GC. How self-determination theory can assist our understanding of the teaching and learning processes in medical education. AMEE guide No. 59. Med Teach. 2011;33(12):961–73.

Wall D, Bolshaw A, Carolan J. From undergraduate medical education to pre-registration house officer year: how prepared are students? Med Teach. 2006;28(5):435–9.

Prescott JE. Important guidance for medical students on clinical rotations during the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. 2020. Cited 2020 Available from: https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/press-releases/important-guidance-medical-students-clinical-rotations-during-coronavirus-covid-19-outbreak.

Theoret C, Ming X. Our education, our concerns: the impact on medical student education of COVID-19. Med Educ. 2020;54(7):591–2.

Schiff A, et al. Results of a near-peer musculoskeletal medicine curriculum for senior medical students interested in orthopedic surgery. J Surg Educ. 2014;71(5):734–7.

Burns R, et al. A brief boot camp for 4th-year medical students entering into pediatric and family medicine residencies. Cureus. 2016;8(2):e488.

Devon EP, et al. A pediatric preintern boot camp: program development and evaluation informed by a conceptual framework. Acad Pediatr. 2019;19(2):165–9.

Hartke A, et al. Building a Boot camp: pediatric residency preparatory course design workshop and tool kit. MedEdPORTAL. 2019;15:10860.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. Elliott contributed to study conception and design, curriculum development and implementation, data collection and analysis, preparation of the initial manuscript draft, and manuscript review.

Dr. Petosa contributed to study conception and design, curriculum development and implementation, data collection and analysis, preparation of the initial manuscript draft, and manuscript review.

Dr. Guiot contributed to study conception and design, curriculum development and implementation, data analysis, and manuscript review.

Dr. Klein contributed to study conception and design, data analysis, and manuscript review.

Dr. Herrmann contributed to study conception and design, data analysis, manuscript review, and project supervision.

All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Elliott, L.E., Petosa, J.J., Guiot, A.B. et al. Qualitative Analysis of a Virtual Near-Peer Pediatric Boot Camp Elective. Med.Sci.Educ. 32, 473–480 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-021-01466-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-021-01466-w