Abstract

Objective

The psychiatric mental status examination is a fundamental aspect of the psychiatric clinical interview. However, despite its importance, little emphasis has been given to evidence-based instructional design. Therefore, this review summarizes the literature from an instructional design perspective with the aim of uncovering design strategies that have been used for teaching the psychiatric interview and mental status examination to health professionals.

Methods

The authors conducted a scoping review. Multiple databases, reference lists, and the gray literature were searched for relevant publications across educational levels and professions. A cognitive task analysis and an instructional design framework was used to summarize and chart the findings.

Results

A total of 61 articles from 17 countries in six disciplines and three educational levels were identified for data extraction and analysis. Most studies were from the USA, presented as educational case reports, and carried out in undergraduate education in the field of psychiatry. Few articles described the instructional rationale for their curriculum. None of the studies compared the effectiveness of different instructional design components. Reported learning activities for each task domain (knowledge, skills, and attitudes) and for each step of an instructional design process were charted. Most articles reported the use of introductory seminars or lectures in combination with digital learning material (videos and virtual patients in more recent publications) and role-play exercises.

Conclusions

Educators in psychiatry should consider all task domains of the psychiatric interview and mental status examination. Currently, there is a lack of empirical research on expertise acquisition and use of instructional design frameworks in this context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Since the first systematic work on psychopathology was done by German psychiatrist and philosopher Karl Jaspers in 1913 [1], administering the mental status examination (MSE) has become a core clinical skill. The first use of the term ‘mental status examination’ has been attributed to the Swiss-American psychiatrist Adolf Meyer [2]. Medical students have to master it based on competency-based undergraduate curricula [3]. The psychiatric interview, including the MSE, is a clinical assessment of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral functioning [4,5,6,7,8]. While memorizing the definitions of psychopathological symptoms and a corresponding sequence of questions may appear to be a straightforward exercise, conducting the MSE in a clinical interview can become an overwhelmingly complex clinical task—especially for novice trainees. This complexity arises from having to conduct the MSE while concurrently easing a patient’s suffering, building a therapeutic alliance, obtaining a psychiatric database, interviewing for a diagnosis, and negotiating a treatment plan under sometimes challenging and diverse conditions [4, 5]. Despite an abundance of literature on each of these elements [4,5,6,7,8,9], and on more general communication skills, evidence and best practice recommendations on instructional design for teaching the MSE as part of the psychiatric interview remain scarce. The authors found only one review that explored quantitative evidence for effectively teaching the MSE, and it highlighted the need for a broader review of instructional methods [10].

Instructional design development typically starts with an analysis of the desired learning outcomes, which, in competency-based medical education, are also termed “whole-tasks,” “complex tasks,” or “entrustable professional activities” (EPAs) [3, 11]. To describe such a task from an expert’s perspective, educators have used cognitive task analysis (CTA) to analyze and structure the relevant knowledge, skills, and attitudes of complex tasks in a range of disciplines—including medicine [12]. Research in other educational fields has shown that instructional designs based on CTA have resulted in a 31–46% post-training performance gain [12]. The next step in instructional design development is to select and orchestrate specific instructional strategies and sequences. This can be done using the four-component instructional design (4C/ID) model [11], which is based on learning tasks (component 1), supportive information (component 2), procedural information (component 3), and part-task practice (component 4) [11]. To our knowledge, CTA and the 4C/ID have not been used for reviewing the educational literature on teaching the MSE as part of a psychiatric interview.

Effective use of the MSE in a psychiatric interview is important not only for psychiatrists. Mental disorders are highly prevalent across health service sectors [13]. An estimated 25% of family practice consultations are for psychiatric reasons, and 26–33% of the population suffers from a common psychiatric disorder at some point in their lives [13, 14]. The chronology of psychiatric disorders has been shown to be longer than that of somatic disorders, and is associated with significant societal costs. Consequently, effective instructional designs for teaching how to assess psychiatric disorders are relevant for a wide range of medical educators and clinical professions.

The aim of this study was to review the literature and synthesize current expert knowledge on the task domains of the MSE as part of the psychiatric interview and to extract information on instructional components. These findings could serve both educators involved in designing longitudinal curricula for clinical interviewing skills of health professionals as well as clinical educators involved in workplace-based curriculum design. A comprehensive understanding of the task domains of the MSE will allow for targeted and situated educational interventions and inform future research in this area.

Methods

The authors conducted a scoping review of the medical education literature and followed the scoping review guidelines of Arksey and O’Malley to identify relevant articles [15]. The research question was: “What instructional design strategies for teaching the psychiatric interview and MSE have been used or studied in the education of health professionals?” For charting the data and collating and summarizing the results, both a cognitive task analysis (CTA) [12] and the four-component instructional design (4C/ID) [11, 16] approach were used to derive instructional design implications and identify research gaps.

Data sources and Search Strategy

The following search terms and Boolean operators were used: “Mental Status Exam,” OR “Mental Status Examination” AND (scholarship OR education OR teaching OR learning OR pedagogy). The search queries were selected based on the MSE commonly being called an exam or examination and paired with synonyms of pedagogic terms. The following databases were searched: Ovid, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Embase, ERIC, MedEdPortal, the archives of Academic Psychiatry, Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations, standard textbooks, the gray literature (e.g., materials and documents that are typically not published in academic journals such as educational material or technical reports), Google scholar (first ten pages), Association of Directors of Medical Student Education in Psychiatry (ADMSEP) resources, and personal files. Only peer reviewed, published journal articles in the English, French, or German languages were considered. The last date search was performed on the PubMed and Academic Psychiatry archives on August 23, 2021.

Screening and Selection of Articles

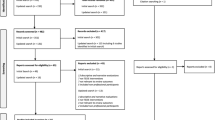

Article titles and abstracts were screened by two authors independently. Articles published since 1970 with direct relevance to teaching content and/or the process of the MSE as part of the psychiatric interview in any clinical health profession were included. Exclusion criteria were as follows: articles that omitted mention of the psychiatric interview (including the MSE) in either the title, abstract, or content, and articles that omitted discussions on teaching methodology. Of special note, the Folstein Mini Mental State Examination was not specifically explored as the authors considered it to be out of scope of this review. Following the recommendations for scoping reviews, article reference lists were searched in duplicate by two of the authors for relevant articles [15]. Their conclusions were then compared for variations and discussed with a third author. Sources of evaluative bias were identified through duplicate analysis. Any discrepancies were discussed between authors until a consensus was established.

Data Extraction, Analysis, and Synthesis of Results

Included articles were initially charted in an Excel table and information regarding educational intervention (medical specialty, educational level, reported educational outcomes, task domains, learning tasks and, if available, instructional design) were extracted. Each article’s extractions were discussed and are synthesized in Table 1 (task domains and corresponding instructional strategies) and Table 2 (instructional design components). We focused on the first of five stages of evidence-based CTA approaches. This involved the identification of target performance goals and a review of general knowledge about task domains to chart relevant terms and processes [12]. In a second step, we used the 4C/ID model by Van Merriënboer [11] to organize, interpret, and synthesize the extracted data according to learning tasks (component 1: authentic professional tasks), supportive information (component 2: how to approach the tasks and how the domain is organized), procedural information (component 3: describing step-by-step procedures to perform routine aspects of the tasks), and part-task practice (component 4: repetition of aspects that need to be automated). An instructional design model for the MSE is depicted in Table 2.

Results

Included Articles

The initial search yielded 4,152 articles. After the removal of duplicates and an independent screening of titles and abstracts by two researchers, the full texts of 101 articles were assessed. In total, 61 articles [2, 10, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76] were used for the data extraction. In addition, six standard psychiatry and psychiatric interviewing textbooks or chapters focusing on the MSE, psychiatric interviewing, and instructional design were identified and screened [4,5,6,7,8,9].

The characteristics and main aspects of the included articles from 17 different countries were summarized descriptively. Most studies were from the USA (n=23.4%), the UK (n=5.8%), and Australia (n=3.5%) but also from South American and Asian countries. Prevalent study types were educational case reports (n=17.3%), cohort studies (n=9.2%), and expert consensus reports (n=6.1%) and less often randomized-controlled trials (n=4.7%) and only one ethnographic study. The studies were typically carried out in psychiatry (n=52.9%), primary care (n=6.1%), and nursing (n=5.8%); however, we also found studies in the context of emergency medicine and psychosomatic medicine. In terms of educational level, n=39.6% of the included studies were carried out at the undergraduate level, n=24.4% on the graduate level, and n=3.5% on the continuing education level. While most studies reported educational outcomes in terms of student satisfaction ratings (n=22.4%), observer-based performance ratings (n=14.2%), and self-assessment of competence (n=7.1%), a large proportion did not report any educational outcome measures (n=17.3%).

The identified main structures for written MSE reporting were juxtaposed with the currently taught MSE reporting structure at our institution and differed only in terms of sequence and level of detail but contained the same elements of psychopathology.

Cognitive Task Analysis

Table 1 depicts the extracted and synthesized relevant knowledge, skills, and attitudes for conducting the MSE during a psychiatric clinical interview. For each domain (knowledge, skills, and attitudes), the reported learning tasks used in the studies were also extracted. Typically, these learning tasks were described as part of an educational intervention and in the context of a set of tasks without explicit reference to learning goals or task domains. However, we were able to identify several discrete learning tasks that could be rearranged and sequenced if needed.

Most articles reported the use of introductory seminars or lectures for teaching the knowledge domain of psychiatric interviews and the MSE in combination with knowledge tests and digital learning material. The latter included expert role modeling in video-recorded interviews and, in more recent publications, different types of virtual patient scenarios (Table 1). To teach clinical interviewing, educators used Virtual Human Agent technology [38], virtual reality scenarios [39], virtual patient programs [40, 41], illness-specific virtual patient systems [42], teaching suicide risk assessment with a virtual patient [43], and a virtual clinic simulator [44]. Moreover, the search yielded role-play exercises as the most frequently reported learning task for different aspects of the skills domain (see Table 1 for specific references). To practice the psychiatric interview and the MSE, educators used actors, clinical experts, more advanced trainees, peer students, or avatars as standardized, simulated, or virtual patients for students.

Another frequently used method was need-based or longitudinally direct or indirect supervision with expert clinicians who provided formative feedback for developing interviewing and examination skills while learners saw real patients. The attitude domain was the least often reported domain in educational interventions and effectiveness evaluations. Depending on the programs’ educational goals, clinical supervisors were the main source of feedback for various domains, which targeted developing an empathic attitude, acquiring self-knowledge, reflecting transference and countertransference, and critical awareness of stigma or prejudices in the context of different world views and personal value systems (see Table 1 for specific references).

Only one systematic review explored the comparative effectiveness of teaching methods for the MSE [10]. The authors reported that non-traditional teaching methods (video-taped interviews, virtual simulations, and standardized patients) tended to achieve higher student satisfaction ratings and better learning outcomes (knowledge and skills) compared to lectures and reading material alone. Due to the heterogeneity of the interventions and outcome parameters, no meta-analysis was performed. Furthermore, no studies were found that compared educational interventions such as lectures or seminars to role play, interview guides, or clinical rotations alone or in different combinations or sequences.

Instructional Strategies

Instructional strategies relevant for developing a complex task course based on the four-component instructional design (4C/ID) model [16] were charted according to the ten steps of the instructional model (Table 2). Only a few articles described the instructional rationale for their curriculum in detail [21, 26, 29, 36, 51, 69]. The most elaborated curriculum was a 2-month, workplace-based psychiatric interview program based on previously published literature and expert opinion by Shea and Mezzich [2]. This article outlined concrete learning goals and a sequence and combination of theoretical training, experiential and self-regulated learning, and direct and indirect supervision. While the educational outcomes were measured only at the learners’ satisfaction level (with overall high satisfaction levels), no comparison with other instructional strategies or sequences was made. The feasibility of implementing such a program in multiple sites was not investigated.

Discussion

In this scoping review, the authors searched the literature for articles on instructional designs for teaching the MSE as part of the psychiatric interview using both a cognitive task analysis (CTA) and a four-component instructional design (4C/ID) model framework. The key result of this review is the synthesis of specific knowledge, skills, and attitudes regarding the MSE within the psychiatric interview and the corresponding instructional design strategies that have been implemented or studied. Educators and researchers could use this as a framework for local curriculum development or educational design studies.

The large body of literature found for this review illustrates that teaching and learning the MSE under workplace-based curricula cannot be separated from conducting a clinical (psychiatric) interview. Therefore, the MSE should not be considered exclusively as a “technical” skill comparable to a physical examination, as suggested by some authors [8]. Instead, it is one element of a specific form of the clinical interview that relies on general interviewing and communication competencies that all physicians need when interacting with patients [4]. For example, end-of-undergraduate-training EPAs in the USA do not have a separate EPA for the MSE. Instead, it is nested within larger activities such as a diagnostic interview, follow-up visit, or emergency management [3]. Only a few articles attempted to address the complex nature of teaching this competence comprehensively, typically at the cost of empirical research designs [21, 57, 61, 66]. The number and breadth of studies (both qualitative and quantitative papers on relevant instructional designs for all task domains of the MSE) included in this review exceeds those that were included in a previous systematic review by Xie and colleagues [10], which was limited to quantitative studies. Specifically, over 15 relevant papers have been published since the Xie et al. review, many of which have used innovative digital instructional designs.

Earlier studies [10, 17, 46] have provided evidence that experiential forms of learning the psychiatric interview and MSE (i.e., through role play and practice with standardized patients) in comparison to didactic teaching methods alone (i.e., lectures and readings) tend to lead to better educational outcomes. This is not surprising in the era of competency-based education. However, even well-designed and more recent studies only marginally describe the rationale for their instructional design (i.e., choice and sequencing of instructional methods) or not at all [25, 36]. There is also a lack of studies investigating what combination of instructional design elements is the most effective for each educational stage on the novice-expert-continuum (pre-clinical student versus clerkship student versus first-year resident versus specialist). Therefore, the findings of this review can provide educators with instructional strategies that take into account each task domain of the MSE and, hence, future research can address questions of sequencing and adjustment for the expertise level of trainees.

Technology-enhanced learning such as annotated or interactive clinical video databases or virtual patient scenarios appear to be cost-effective options (especially for novice learners) and can help to ensure that all learners are exposed to the same range of clinical presentations independent of the clinical context of a clerkship rotation [2, 17, 19, 23, 30,31,32, 36, 38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. This is also relevant from a patient safety perspective as it ensures that every student develops basic competencies before seeing real patients. In one randomized-controlled trial, there was no significant learning performance differences when comparing video-based and virtual patient scenarios, but students preferred video-based instruction [43]. Similar study designs that compare variations of the same instructional method (e.g., role-play with versus without specific introductions to this learning method [61]) would be helpful for evidence-based instructional design recommendations. The details of an instructional design might have an impact on the acceptance of the learning method and transfer of acquired knowledge into clinical practice. Given the challenges with the authenticity of simulated clinical interviews, learner anxiety over performing a clinical interview in front of an audience, and the potential lack of confidence in these instructional methods [43, 61], it may be worthwhile to explore the added value of investing time and resources in evidence-based instructional design. An emerging area of educational research is the use of digital learning environments for teaching the MSE and psychiatric interview (e.g., virtual patient scenarios). The instructional design formats identified in this scoping review might inform future research questions and study designs.

This scoping review has several limitations. First, while studies from 17 different countries were included, this was a non-representative sample. Psychiatry as discipline is deeply embedded in the linguistic and cultural context where it is practiced. Therefore, important perspectives on teaching and learning the clinical psychiatric interview and MSE in other countries and regions may have been missed. In addition, successfully implemented educational material and concepts might not always be translated and published in scholarly journals. Moreover, academic institutions might not systematically support the scholarship of teaching and learning the MSE and the clinical psychiatric interview even though this would be necessary for sharing knowledge and advancing the field. Second, the authors’ own biases may have affected how these records were perceived as all of the authors work in the field of health care. Non-medical professionals or patients might have made different determinations. Third, under-researched teaching and learning situations in the context of the psychiatric interview and MSE such as accounting for cultural diversity, using digital interviewing formats, interviewing geriatric patients, or forensic psychiatric interviewing were not represented in this review and warrant further attention.

In conclusion, educators involved in the design of MSE curricula and the psychiatric interview—or in longitudinal communication curricula—should consider all the task domains of the psychiatric interview early in undergraduate training and deliberate on instructional design and the potential synergies between disciplines. While not all identified task domains can be covered in short clerkship rotations, it seems worthwhile to invest time in understanding which task domains of the psychiatric interview might already be covered in other communication skills trainings (e.g., in pre-clinical sessions or breaking-bad news training in other medical disciplines), and which not. Ideally, a psychiatry clerkship curriculum would build on and inform longitudinal communication curricula involving other disciplines or residency programs. The four-component instructional design model can be used to identify potential gaps in a given curriculum and lead to adding or adjusting instructional methods.

While a broad range of instructional methods has been used in various educational contexts for teaching the psychiatric interview and MSE, no clear standard for an instructional design has emerged. We suggest using the available evidence for developing instructional design blueprints for teaching the psychiatric interview. Future research should explore facets of expertise acquisition in conducting the psychiatric interview and the educational benefit of novel digital learning environments in this context.

References

Jaspers K. Allgemeine Psychopathologie. Ein Leitfaden für Studierende, Ärzte und Psychologen. [German for: General psychopathology. A guide for students, physicians and psychologists]. Berlin: Julius Springer; 1913.

Shea SC, Mezzich JE. Contemporary psychiatric interviewing: new directions for training. Psychiatry. 1988;51(4):385–97.

Pinilla S, Lenouvel E, Cantisani A, Klöppel S, Strik W, Huwendiek S, Nissen C. Working with entrustable professional activities in clinical education in undergraduate medical education: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):1–10.

Shea SC. Psychiatric interviewing: the art of understanding. 3rd ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2017.

Carlat DJ. The psychiatric interview. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2017.

Haug A. Psychiatrische Untersuchung: Ein Leitfaden für Studierende, Ärzte und Psychologen in Praxis und Klinik [German for: Psychiatric examination: a practical guide for students, physicians and psychologists in private practices and hospitals]. 2017.

AMDP. Das AMDP-System: Manual zur Dokumentation psychiatrischer Befunde [German for: The comprehensive psychopathological assessment based on the Association for Methodology and Documentation in Psychiatry (AMDP)-System: manual for documention of psychiatric symptoms]. 10., korrigierte Auflage ed. Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe; 2018.

Boland R, Verduin M, Ruiz P, editors. Kaplan & Sadock's synopsis of psychiatry. 12th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2021.

Berger M, editor. Psychische Erkrankungen: Klinik und Therapie [German for: Mental diseases: clinical presentations and therapy]. 6th ed. Munich: Elsevier; 2018.

Xie H, Liu L, Wang J, Joon KE, Parasuram R, Gunasekaran J, Poh CL. The effectiveness of using non-traditional teaching methods to prepare student health care professionals for the delivery of mental state examination: a systematic review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports. 2015;13(7):177–212.

van Merrienboer JJ, Dolmans DH. Research on instructional design in the health sciences: from taxonomies of learning to whole-task models. In: Cleland J, Durning SJ, editors. Researching medical education. 1st ed. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: The Association for the Study of Medical Education, John Wiley & Sons; 2015. p. 193–206.

Clark R. Cognitive task analysis for expert-based instruction in healthcare. In: Spector JM et al (eds.) Handbook of research on educational communications and technology. Springer; 2014. pp 541–51.

Steel Z, Marnane C, Iranpour C, Chey T, Jackson JW, Patel V, Silove D. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):476–93.

Smith RC, Laird-Fick H, D’Mello D, Dwamena FC, Romain A, Olson J, Kent K, Blackman K, Solomon D, Spoolstra M, Fortin AH VI, Frey J, Ferenchick G, Freilich L, Meerschaert C, Frankel R. Addressing mental health issues in primary care: an initial curriculum for medical residents. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94(1):33–42.

Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International journal of social research methodology. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Vandewaetere M, Manhaeve D, Aertgeerts B, Clarebout G, Van Merriënboer JJ, Roex A. 4C/ID in medical education: how to design an educational program based on whole-task learning: AMEE Guide No. 93. Med Teach. 2015;37(1):4–20.

Pohl R, Lewis R, Niccolini R, Rubenstein R. Teaching the mental status examination: comparison of three methods. J Med Educ. 1982;57(8):626–9.

Lovett L, Cox A, Abou-Saleh M. Teaching psychiatric interview skills to medical students. Med Educ. 1990;24(3):243–50.

Kendrick T, Burns T, Freeling P. Randomised controlled trial of teaching general practitioners to carry out structured assessments of their long term mentally ill patients. BMJ. 1995;311(6997):93–7.

Birndorf CA, Kaye ME. Teaching the mental status examination to medical students by using a standardized patient in a large group setting. Acad Psychiatry. 2002;26(3):180–3.

Shea SC, Green R, Barney C, Cole S, Lapetina G, Baker B. Designing clinical interviewing training courses for psychiatric residents: a practical primer for interviewing mentors. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30(2):283–314.

de Azevedo Marques JM, Zuardi AW. Validity and applicability of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview administered by family medicine residents in primary health care in Brazil. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(4):303–10.

Talley BJ, Littlefield J. Efficiently teaching mental status examination to medical students. Med Educ. 2009;43(11):1100–1.

Benthem GHH, Heg RR, van Leeuwen YD, Metsemakers JFM. Teaching psychiatric diagnostics to general practitioners: educational methods and their perceived efficacy. Med Teach. 2009;31(7):e279–86.

Fernandez-Liria A, Rodriguez-Vega B, Ortiz-Sanchez D, Baldor Tubet I, Gonzalez-Juarez C. Effectiveness of a structured training program in psychotherapeutic skills used in clinical interviews for psychiatry and clinical psychology residents. Psychother Res. 2010;20(1):113–21.

Lehmann SW. A longitudinal “teaching-to-teach” curriculum for psychiatric residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2010;34(4):282–6.

Goh Y-S, Selvarajan S, Chng M-L, Tan C-S, Piyanee Y. Using standardized patients in enhancing undergraduate students' learning experience in mental health nursing. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;45:167–72.

Beach SR, Taylor JB, Kontos N. Teaching psychiatric trainees to “think dirty”: uncovering hidden motivations and deception. Psychosomatics. 2017;58(5):474–82.

Wichser L, Homans J, Leppink EW, Savage W, Nelson KJ. The Minnesota Arc: a new model for teaching the psychiatric interview to medical students serving on their psychiatry clerkship. Acad Psychiatry. 2021;45:1–4.

Mankey VL. Using multimodal and multimedia tools in the psychiatric education of diverse learners: examples from the mental status exam. Acad Psychiatry. 2011;35(5):335–9.

Ton H, Xiong G, Méndez L, Hilty D, Price L, Brescia R, Patron D. The psychiatric interview: a self-directed learning module. MedEdPORTAL. 2013;9

Griffeth BT, Brooks WB, Foster A. A psychiatric-specific entrustable professional activity for the evaluation of prospective psychiatric residents: towards a national standard. MedEdPORTAL: the journal of teaching and learning resources. 2017;13:10584.

Fog-Petersen C, Borgnakke K, Hemmingsen R, Gefke M, Arnfred S. Clerkship students’ use of a video library for training the mental status examination. Nordic journal of psychiatry. 2020;74(5):332–9.

Hansen JR, Gefke M, Hemmingsen R, Fog-Petersen C, Høegh EB, Wang A, Arnfred SM. E-library of authentic patient videos improves medical students’ mental status examination. Acad Psychiatry. 2020;44(2):192–5.

Martin A, Jacobs A, Krause R, Amsalem D. The mental status exam: an online teaching exercise using video-Based depictions by simulated patients. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:10947.

Martin A, Krause R, Jacobs A, Chilton J, Amsalem D. The mental status exam through video clips of simulated psychiatric patients: an online educational resource. Academic psychiatry : the journal of the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training and the Association for Academic Psychiatry. 2020;44(2):179–83.

Simpson SA, Sakai J, Rylander M. A free online video series teaching verbal de-escalation for agitated patients. Acad Psychiatry. 2020;44(2):208–11.

Parsons TD, Kenny P, Ntuen CA, Pataki CS, Pato MT, Rizzo AA, St-George C, Sugar J. Objective structured clinical interview training using a virtual human patient. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2008;132:357–62.

Kidd LI, Knisley SJ, Morgan KI. Effectiveness of a Second Life® simulation as a teaching strategy for undergraduate mental health nursing students. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2012;50(7):28–37.

Lin C-C, Wu W-C, Liaw H-T, Liu C-C. Effectiveness of a virtual patient program in a psychiatry clerkship. Med Educ. 2012;46(11):1111–2.

Shah H, Rossen B, Lok B, Londino D, Lind SD, Foster A. Interactive virtual-patient scenarios: an evolving tool in psychiatric education. Acad Psychiatry. 2012;36(2):146–50.

Ekblad S, Mollica RF, Fors U, Pantziaras I, Lavelle J. Educational potential of a virtual patient system for caring for traumatized patients in primary care. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13(1):1–12.

Foster A, Chaudhary N, Murphy J, Lok B, Waller J, Buckley PF. The use of simulation to teach suicide risk assessment to health profession trainees—rationale, methodology, and a proof of concept demonstration with a virtual patient. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(6):620–9.

Matsumura Y, Shinno H, Mori T, Nakamura Y. Simulating clinical psychiatry for medical students: a comprehensive clinic simulator with virtual patients and an electronic medical record system. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42(5):613–21.

Singer PR, Muslin HL. Evaluation and teaching of psychiatric interviewing. Compr Psychiatry. 1970;11(4):371–6.

Rimondini M, Del Piccolo L, Goss C, Mazzi M, Paccaloni M, Zimmermann C. The evaluation of training in patient-centred interviewing skills for psychiatric residents. Psychol Med. 2010;40(3):467–76.

Bajgier J, Bender J, Ries R. Use of templates for clinical documentation in psychiatric evaluations-beneficial or counterproductive for residents in training? Int J Psychiatry Med. 2012;43(1):99–103.

Bass D, Brandenburg D, Danner C. The pocket psychiatrist: tools to enhance psychiatry education in family medicine. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2015;50(1):6–16.

Amad A, Geoffroy PA, Micoulaud-Franchi J-A, Bensamoun D, Benzerouk F, Peyre H, et al. A standardized psychiatric clinical examination for students is possible! Ann Med Psychol (Paris). 2018;176:936–40.

Daniels-Brady C, Rieder R. An assigned teaching resident rotation. Acad Psychiatry. 2010;34(4):263–8.

Huline-Dickens S, Heffernan E, Bradley P, Coombes L. Teaching and learning the mental state exam in an integrated medical school. Part I: Student perceptions. The Psychiatric Bulletin. 2014;38(5):236–42.

Huline-Dickens S, Heffernan E, Bradley P, Coombes L. Teaching and learning the mental state exam in an integrated medical school. Part II: Student performance. The Psychiatric Bulletin. 2014;38(5):243–8.

Hickie C, Nash L, Kelly B. The role of trainees as clinical teachers of medical students in psychiatry. Australasian Psychiatry. 2013;21(6):583–6.

Recupero PR, Rumschlag JS, Rainey SE. The mental status exam at the movies: the use of film in a behavioral medicine course for physician assistants. Acad Psychiatry. 2021:1-6; https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-021-01463-6.

Bowman F, Goldberg D, Millar T, Gask L, McGrath G. Improving the skills of established general practitioners: the long-term benefits of group teaching. Med Educ. 1992;26(1):63–8.

Bennett AJ, Arnold LM, Welge JA. Use of standardized patients during a psychiatry clerkship. Acad Psychiatry. 2006;30(3):185–90.

Shea SC, Barney C. Macrotraining: a “how-to” primer for using serial role-playing to train complex clinical interviewing tasks such as suicide assessment. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30(2):e1–e29.

Brenner AM. Uses and limitations of simulated patients in psychiatric education. Acad Psychiatry. 2009;33(2):112–9.

Chaturvedi SK, Chandra PS. Postgraduate trainees as simulated patients in psychiatric training: role players and interviewers perceptions. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52(4):350–4.

King J, Hill K, Gleason A. All the world’sa stage: evaluating psychiatry role-play based learning for medical students. Australasian Psychiatry. 2015;23(1):76–9.

Shea SC, Barney C. Teaching clinical interviewing skills using role-playing: conveying empathy to performing a suicide assessment: a primer for individual role-playing and scripted group role-playing. Psychiatric Clinics. 2015;38(1):147–83.

Himmelbauer M, Seitz T, Seidman C, Löffler-Stastka H. Standardized patients in psychiatry–the best way to learn clinical skills? BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):1–6.

Mahendran R, Lim HMA, Kua EH. Medical students' experiences in learning the Mental State Examination with standardized patients. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry. 2019;11(4):e12360.

Junek W, Burra P, Leichner P. Teaching interviewing skills by encountering patients. J Med Educ. 1979;54(5):402–7.

Ness DE, Kiesling SF. Language and connectedness in the medical and psychiatric interview. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;68(2):139–44.

Shea SC, Barney C. Facilic supervision and schematics: the art of training psychiatric residents and other mental health professionals how to structure clinical interviews sensitively. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30(2):e51–96.

Dalack GW, Jibson MD. Clinical skills verification, formative feedback, and psychiatry residency trainees. Acad Psychiatry. 2012;36(2):122–5.

Jibson MD, Broquet KE, Anzia JM, Beresin EV, Hunt JI, Kaye D, Rao NR, Rostain AL, Sexson SB, Summers RF, ABPN Task Force on Clinical Skills Verification Rater Training. Clinical skills verification in general psychiatry: recommendations of the ABPN Task Force on Rater Training. Acad Psychiatry. 2012;36(5):363–8.

Meyer EG, Battista A, Sommerfeldt JM, West JC, Hamaoka D, Cozza KL. Experiential learning cycles as an effective means for teaching psychiatric clinical skills via repeated simulation in the psychiatry clerkship. Acad Psychiatry. 2021;45(2):150–8.

Fuehrlein B, Bhalla I, Goldenberg M, Trevisan L, Wilkins K. Simulate to stimulate: manikin-based simulation in the psychiatry clerkship. Acad Psychiatry. 2020;44(1):82–5.

Ruegg RG, Ekstrom D, Evans DL, Golden RN. Introduction of a standardized report form improves the quality of mental status examination reports by psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 1990;14(3):157–63.

Patel M, Hui J, Ho C, Mak CK, Simpson A, Sockalingam S. Tutors’ perceptions of the transition to video and simulated patients in pre-clinical psychiatry training. Acad Psychiatry. 2021;45:1–5.

Parker S, Leggett A. Teaching the clinical encounter in psychiatry: a trial of Balint groups for medical students. Australasian Psychiatry. 2012;20(4):343–7.

Horton-Deutsch S, McNelis AM, Day POH. Developing a reflection-centered curriculum for graduate psychiatric nursing education. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2012;26(5):341–9.

Scardovi A, Rucci P, Gask L, Berardi D, Leggieri G, Ceroni GB, Ferrari G. Improving psychiatric interview skills of established GPs: evaluation of a group training course in Italy. Fam Pract. 2003;20(4):363–9.

Huline-Dickens S. The mental state examination. Advances in psychiatric treatment. 2013;19(2):97–8.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Bern.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lenouvel, E., Chivu, C., Mattson, J. et al. Instructional Design Strategies for Teaching the Mental Status Examination and Psychiatric Interview: a Scoping Review. Acad Psychiatry 46, 750–758 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-022-01617-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-022-01617-0