Abstract

Background and Objective

Suicidal ideation or behavior are core symptoms of major depressive disorder (MDD). This study aimed to understand heterogeneity among patients with MDD and acute suicidal ideation or behavior.

Methods

Adults with a diagnosis of MDD on the same day or 6 months before a claim for suicidal ideation or behavior (index date) were identified in the MarketScan® Databases (10/01/2014–04/30/2019). A mathematical algorithm was used to cluster patients on characteristics of care measured pre-index. Patient care pathways were described by cluster during the 12-month pre-index period and up to 12 months post-index.

Results

Among 38,876 patients with MDD and acute suicidal ideation or behavior, three clusters were identified. Across clusters, pre-index exposure to mental healthcare was revealed as a key differentiator: Cluster 1 (N = 16,025) was least exposed, Cluster 2 (N = 5640) moderately exposed, and Cluster 3 (N = 17,211) most exposed. Patients whose MDD diagnosis was first observed during their index event comprised 86.0% and 72.8% of Clusters 1 and 2, respectively; in Cluster 3, all patients had an MDD diagnosis pre-index. Within 30 days post-index, in Clusters 1, 2, and 3, respectively, 79.3%, 85.2%, and 88.2% used mental health services, including outpatient visits for MDD. Within 12 months post-index, 61.5%, 91.5%, and 84.6% had one or more antidepressant claim, respectively. Per-patient index event costs averaged $5614, $6645, and $5853, respectively.

Conclusions

Patients with MDD and acute suicidal ideation or behavior least exposed to the healthcare system pre-index similarly received the least care post-index. An opportunity exists to optimize treatment and follow-up with mental health services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A data-driven process identified distinct clusters of patients with major depressive disorder and acute suicidal ideation or behavior. |

Degree of exposure to the mental healthcare system before the suicide-related event was the key differentiator across clusters. |

Clusters least exposed to the healthcare system before the suicide-related event received the least care after it. |

1 Background

Major depressive disorder (MDD) affects 7.8% of adults in the USA annually [1] and is a leading cause of disability worldwide [2, 3]. Major depressive disorder is a heterogeneous disorder with symptoms varying in number, frequency, intensity, and impact on function over the course of illness. Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide attempts are among the core symptoms of MDD [4]. In 2017, the estimated prevalence of past-year suicidal ideation among US adults with MDD was 31%, a proportion that increased from 26% in 2009 [5]. Major depressive disorder is among the most prevalent conditions associated with suicide [6].

Despite mental health parity laws, many patients with mental health conditions face barriers in access to optimal mental healthcare [7, 8]. Despite an extensive body of literature on MDD, little is known about the subset of patients with MDD and acute suicidal ideation or behavior (MDSI) and the way these patients interact with the healthcare system before and after the suicide-related event. To improve the care for patients with MDSI, it is important to understanding whether different patient sub-types exist within this population. Knowledge of the real-world care pathways by patient sub-types may aid clinicians and health systems in designing targeted treatment strategies. Thus, this study aimed to identify distinct clusters of patients with MDSI and describe care pathways (i.e., specialized mental health service use, pharmacotherapy use, healthcare resource utilization, and costs) by cluster.

2 Methods

2.1 Data Source

The IBM® MarketScan® Commercial and Medicare Supplemental Databases (10/01/2014–04/30/2019) were used. The data contain patient demographics (race unavailable) and insurance eligibility information, medical and prescription drug claims including paid amounts, and represent all US census regions with concentration in the South and North Central (Midwest). Data are de-identified and comply with patient requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

2.2 Study Design

This study had a retrospective longitudinal design. The study period spanned from 10/01/2014 to 04/30/2019; the index window began on 10/01/2015. Suicide-related events were defined using recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [9]. The index date was the first claim with either a suicidal ideation diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM]: R45.851), or a suicide attempt code (ICD-10-CM: T14.91x), or an intentional self-harm code likely due to a suicide attempt (see Table S1 of the Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM]); any of the three had to be accompanied on the same day or in the 6 months prior by a claim with an MDD diagnosis (ICD-9-CM: 292.2x, 296.3x; ICD-10-CM: F32.xx [excluding F32.8x], F33.xx [excluding F33.8x]), to select patients with a suicide-related event likely associated with a recent major depressive episode. If the index date was based on an intentional self-harm code, a suicidal ideation diagnosis was required on the same day or within the next 30 days to increase the likelihood of the intentional self-harm being related to a suicide attempt. The index suicidal ideation or behavior claim defined the index event, which was categorized by care setting (i.e., inpatient, emergency room [ER], or outpatient). Index events were considered inpatient if they occurred in an inpatient care setting or in an outpatient setting but were preceded (e.g., possibility unrecorded diagnosis codes) or followed (e.g., possibility of an increase in symptom severity) by an inpatient admission within 2 days. Additionally, index events in an ER setting that were followed by an inpatient admission within 3 days were considered as inpatient (e.g., possibility of an increase in symptom severity or an imperfect capture of timing of transfers between ER and inpatient settings in claims data). The duration of outpatient or ER index events was taken as 1 day, while the duration of inpatient index events spanned admission (or index date if it occurred before admission) to discharge. The pre-index period spanned the 12 months before the index event, and the post-index period spanned the index date until the end of continuous insurance eligibility or data for a maximum of 12 months.

2.3 Patient Population

Patients were required to have a claim for suicidal ideation or behavior accompanied by a recent MDD diagnosis (see Sect. 2.2). In addition, patients were ≥ 18 years old as of the index date and had ≥ 12 months of continuous insurance eligibility before the index date. Patients with a diagnosis for bipolar disorder, Cluster B personality disorders, dementia, intellectual disability, schizophrenia and other non-mood psychotic disorders, or substance-induced mood disorders during the baseline or follow-up periods were excluded.

2.4 Patient Characteristics and Care Pathways

Patient characteristics described per-index event included, among others, the timing of the first observed MDD diagnosis (any time before the index event vs during the index event), diagnoses for selected co-occurring conditions (see Tables S2 and S3 of the ESM), proportion of days covered by antidepressants pre-index, and antidepressant use at the time of the index date. Antidepressant use at the time of the index date was defined as ≥ 1 day of supply of monotherapy or argumentation therapy (see definition below) within 14 days before the index date.

Care pathways described both pre-index and post-index included specialized mental health service use, involvement in outpatient care for MDD, antidepressant use, recurrence (post-index only), and healthcare costs. Specialized mental health service use included specialist visits (see Table S4 of the ESM), as well as psychotherapy visits and mental health evaluations (i.e., psychiatric diagnostic evaluations and psychological and neuropsychological assessment and testing) identified with procedure codes.

Involvement in outpatient mental health care for MDD was categorized as predominantly specialized or primary. Patients were classified as predominantly involved in specialized mental healthcare if ≥ 50% of outpatient MDD claims were from specialists (see Table S4 of the ESM); otherwise, patients were classified as predominantly involved in primary mental healthcare.

Antidepressant use (monotherapy and augmentation therapy) was based on days of medication supply in pharmacy claims. Antidepressant augmentation therapy was defined as an overlap of ≥ 60 consecutive days of medication supply without gaps > 7 days between either two or more antidepressants or one or more augmentation agent (i.e., selected anticonvulsants, mood stabilizers, non-benzodiazepine gamma aminobutyric acid receptor modulators, psychostimulants, second-generation antipsychotics, and thyroid hormones) and one or more antidepressant. Patients with antidepressant use and no evidence of augmentation therapy were considered to be receiving monotherapy.

Recurrence was defined as a suicidal ideation or behavior event occurring post-index in either an inpatient or ER setting and without inpatient admissions within 2 days prior. Healthcare costs during the pre-index and post-index periods, and during the index event, were adjusted for inflation using the medical care component of the US Consumer Price Index and reported from the private payer’s perspective (i.e., commercial insurance paid amounts) in 2019 USD.

2.5 Statistical Analysis

2.5.1 Clustering Approach

Hierarchical clustering is a data-driven algorithm that identifies unique clusters with the objective of combining observations with similar characteristics while creating distinct clusters that are different from each other [10, 11]. Fifteen patient characteristics measured during the pre-index period or during the index event were chosen to cluster patients based on a clinical consensus and understanding of potential sources of heterogeneity among patients; selected characteristics were grouped into overlapping sets. Overall, 11 different sets of characteristics were considered in the clustering algorithm (see Table 1). For example, set 2 included the type of care setting at the index event and the timing of the first observed MDD diagnosis.

For each set of selected characteristics, hierarchical clustering was performed iteratively using different linkage methods to divide patients into every possible combination of clusters, from 1 to the number of observations, based on the distance between observations (see Sect. 5 of the ESM). The distance metric used was Manhattan (or Taxicab) [12] for categorical data (binary indicators were created for each category) and Euclidean for continuous data [13]. After hierarchical clustering was completed, silhouette width [14], a measure of distance between observations within a cluster relative to the distance to the next nearest cluster, was calculated for 2–20 clusters, inclusively. The upper bound of 20 clusters was selected because a meaningful interpretation of differences across clusters was deemed difficult beyond that number. Monte Carlo simulations, in which reshuffling created a new dataset with the same univariate distribution of each characteristic but by construction only one cluster, showed that the silhouette width displayed a bias towards a larger number of clusters. Consequently, a novel approach calculating a corrected measure of silhouette width as the raw silhouette width minus the measure of bias obtained from the simulations was implemented. For each set of characteristics, the number of clusters maximizing corrected silhouette width was chosen.

The final set of characteristics to cluster patients on was selected to achieve two objectives: to maximize (1) the number of characteristics included and (2) the fraction of the variation in all included characteristics, combined and individually, explained by clusters. Table 1 illustrates that these are competing objectives: while the number of characteristics used in clustering, generally, increases from left to right, the fraction of variation in included characteristics explained by clusters, generally, declines. The final set (set 5 in Table 1) was selected to find a balance between competing objectives of clustering. It included five characteristics and yielded three clusters, which explained 53.6% of the variation in included characteristics combined; individually, the fraction of explained variation in each characteristic ranged from 18.6% (psychotherapy use) to 84.7% (involvement in outpatient care for MDD). The only other set of characteristics, which resulted in clusters that explained a higher fraction of variation in included characteristics, was set 1. As this set included two characteristics and yielded four clusters out of a possible six, the clustering was considered close to simple cross-tabulation and was not further explored. The final set included the following characteristics: timing of the first MDD diagnosis, proportion of days covered by antidepressants pre-index, antidepressant use at index, psychotherapy use, and involvement in outpatient care for MDD.

2.5.2 Statistical Comparisons

Post-index, Cluster 1 was separately compared to Clusters 2 and 3, and Cluster 2 was compared to Cluster 3. Chi-square tests were used to compare proportions. Univariate linear models were used to estimate cost differences while 95% confidence intervals and p values were estimated using non-parametric bootstrap procedures (N = 499).

3 Results

3.1 Study Population and Clusters

Among 38,876 patients (see Fig. S6 of the ESM for the sample selection process) with MDSI (mean age 34.7 years, 57.4% female; Table 2), 18.8% were identified with suicidal behavior and 81.2% with suicidal ideation at the index event. The algorithm separated patients into three clusters: Cluster 1 (N = 16,025), Cluster 2 (N = 5640), and Cluster 3 (N = 17,211). Patients in Cluster 1 were younger (mean age 31.5 years vs 38.7 and 36.3 years in Clusters 2 and 3; Table 2), with equal sex distribution (patients in Clusters 2 and 3 predominantly women), and a lower prevalence of other mental health (36.5% vs 71.7% and 79.3% in Clusters 2 and 3) and physical health (27.7% vs 47.3% and 45.8% in Clusters 2 and 3) diagnoses pre-index.

In Cluster 1, few patients had an observed MDD diagnosis any time before the index date (14.0%; Fig. 1); in Cluster 2, approximately a quarter had an observed MDD diagnosis, and in Cluster 3, all patients had it. Interestingly, the majority of patients in Clusters 1 and 2 had no observed MDD diagnoses before the index date despite the fact that nearly all (82.1% and 97.5%, respectively, Table 2) had an all-cause outpatient visit (i.e., a potential annual check-up) pre-index. Furthermore, 71.7% of Cluster 2 received a diagnosis for another mental health condition pre-index, with the most common being an anxiety disorder (56.3%).

Timing of major depressive disorder (MDD) diagnosis (before or during suicide-related event) among patients with major depressive disorder with acute suicidal ideation or behavior (MDSI). SIB suicidal ideation or behavior. aBased on claims over the entire study period prior to the SIB (index) event and not restricted to claims in the 12-month pre-index period

In Cluster 1, none of the patients were receiving antidepressant therapy at the time of the index event, while in Clusters 2 and 3, all and two-thirds were on antidepressant therapy, respectively. The mean duration of the post-index period was similar across clusters: 8.4 months in Cluster 1, 8.5 months in Cluster 2, and 8.2 months in Cluster 3 (Table 2).

3.2 Specialized Mental Health Service Use and Outpatient Care for MDD

In the 30 days pre-index, the proportion of patients with any specialized mental health service use or an outpatient visit for MDD varied across clusters, being the lowest in Cluster 1 (12.5%), followed by Cluster 2 (27.9%), and then Cluster 3 (73.0%; Fig. 2a). In the 30 days post-index, these proportions increased, but were still lower in Cluster 1 (79.3%) relative to Clusters 2 and 3 (85.2% and 88.2%, respectively; all p < 0.01) and in Cluster 2 relative to Cluster 3 (p < 0.01).

Proportion of patients with major depressive disorder with acute suicidal ideation or behavior (MDSI) and a visit 30 days before and after suicide-related event for a any specialized mental health visit, b outpatient visit for major depressive disorder (MDD), c specialist, d psychotherapy, and e mental health evaluation. aAny specialized mental health visit includes outpatient care for MDD, specialist visits, psychotherapy visits, and mental health evaluations. bOutpatient visit for MDD was identified based on outpatient claims with an MDD diagnosis. cSpecialist visits were identified based on claims with a provider type, place of service, or revenue code for the following: inpatient psychiatric care/facility, intensive outpatient psychiatric program, intensive psychiatric care, mental health facility, psychiatric clinic, psychiatric facility partial hospitalization, psychiatric nurse, psychiatric residential treatment center, psychiatrist, or psychologist. dPsychotherapy visits were identified among all patients based on claims with the corresponding procedure codes. eMental health evaluations (i.e., psychiatric diagnostic evaluations and psychological and neuropsychological assessment and testing) were identified among all patients (not only patients with a specialist visit) based on claims with the corresponding procedure codes

The use of services during the entire pre-index and post-index periods appeared driven by care within 30 days pre-index and post-index, especially for Cluster 1 (Fig. 3). Specifically, 60.2% in Cluster 1 had a specialist visit in the 30 days post-index and 64.4% over the entire post-index period. Post-index, proportions of patients with outpatient visits for MDD and specialized mental health service use were lower in Cluster 1 vs Clusters 2 and 3 (Fig. 3; all p < 0.01), and in Cluster 2 vs Cluster 3 (all p < 0.01 with the exception of specialist visits, p = 0.12).

Proportion of patients with major depressive disorder with acute suicidal ideation or behavior (MDSI) and a visit during pre-index and post-index periods for a any specialized mental health visit, b outpatient visit for major depressive disorder (MDD), c specialist, d psychotherapy, and e mental health evaluation. PC predominantly involved in primary mental healthcare. aPre-index period is the 12-month period pre-index event. The mean duration of post-index period is 8.3 months for the overall population, 8.4 months for cluster 1, 8.5 months for clusters 2, and 8.2 months for cluster 3. bAny specialized mental health visit includes outpatient care for MDD, specialist visits, psychotherapy visits, and mental health evaluations. cOutpatient visit for MDD was characterized as follows: PC if ≥ 50% of outpatient claims with an MDD diagnosis were with specialists, or PC if <50% of outpatient claims with an MDD diagnosis were with specialists. dSpecialist visits were identified based on claims with a provider type, place of service, or revenue code for the following: inpatient psychiatric care/facility, intensive outpatient psychiatric program, intensive psychiatric care, mental health facility, psychiatric clinic, psychiatric facility partial hospitalization, psychiatric nurse, psychiatric residential treatment center, psychiatrist, or psychologist. ePsychotherapy visits were identified among all patients based on claims with the corresponding procedure codes. fMental health evaluations (i.e., psychiatric diagnostic evaluations and psychological and neuropsychological assessment and testing) were identified among all patients (not only patients with a specialist visit) based on claims with the corresponding procedure codes

Across clusters, outpatient care for MDD during both the pre-index and post-index periods was predominantly primary care. Among patients with an outpatient visit for MDD pre-index (Cluster 3 only), the proportion of patients involved in specialized outpatient mental healthcare increased from 26.1% pre-index to 35.5% post-index (Fig. 3b).

3.3 Antidepressant Use

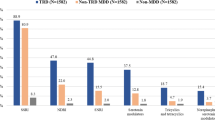

The proportion of patients using antidepressants varied considerably across clusters (Fig. 4). Pre-index, in Cluster 1, 15.2% used antidepressants, while in Clusters 2 and 3 these proportions were 100.0% and 85.2%, respectively. Post-index, the proportion of patients using antidepressants increased in Cluster 1 (61.5%), but still was significantly lower vs Clusters 2 and 3 (91.5% and 84.6%, respectively; all p < 0.01); in Cluster 2, this proportion was significantly higher than in Cluster 3 (p < 0.01). The proportion of patients using antidepressant augmentation therapy increased from pre-index to post-index in Cluster 1 (1.6–11.5%), Cluster 2 (25.4–38.3%), and Cluster 3 (27.9–35.6%). Post-index, it was significantly lower in Cluster 1 vs other clusters (all p < 0.01), and higher in Cluster 2 vs 3 (p < 0.01).

Proportion of patients with major depressive disorder with acute suicidal ideation or behavior (MDSI) using antidepressant therapy during pre- and post-index periods. AD aug antidepressant augmentation therapy, AD mono antidepressant monotherapy. aAntidepressant augmentation therapy was defined as an overlapping coverage for ≥ 60 consecutive days with no gaps > 7 days of either ≥2 antidepressant agents, or ≥ 1 augmentation agent and ≥1 antidepressant agent. Antidepressant monotherapy was defined as patients with ≥ 1 claim for an antidepressant agent who did not meet the criteria for antidepressant augmentation therapy. bPre-index period is the 12-month period pre-index event. The mean duration of post-index period is 8.3 months for the overall population, 8.4 months for cluster 1, 8.5 months for cluster 2, and 8.2 months for cluster 3

The 38.5% of patients in Cluster 1 without antidepressant use post-index appeared only slightly younger than Cluster 1 overall (mean age 30.7 vs 31.5 years), with a slightly higher proportion of men (52.9% vs 49.8%). In this subset, 30.6% neither had outpatient visits for MDD nor used specialized mental health services compared with 16.2% in Cluster 1 overall.

3.4 Recurrence

The proportion of patients with a coded subsequent suicidal ideation or behavior event post-index was lower in Cluster 1 (5.4%) vs Clusters 2 and 3 (7.8% and 8.4%, respectively; all p < 0.01), and lower in Cluster 2 vs Cluster 3 (p = 0.02).

3.5 Care Setting for Index Event and Related Costs

Across clusters, 56.9% (Cluster 3) to 63.7% (Cluster 2) received care during the index event in an inpatient setting, 28.4% (Cluster 2) to 32.7% (Cluster 1) presented at an ER and did not receive inpatient services, and 8.0% (Cluster 1) to 13.1% (Cluster 3) were cared for at an outpatient setting (Table 2). Mean costs of care for index events in inpatient and ER settings exceeded mean monthly costs of care for pre-index and post-index periods (Fig. 5). Mean index event costs, driven by the proportion of patients cared for in an inpatient setting, were significantly lower in Cluster 1 ($5614) relative to Clusters 2 and 3, and in Cluster 3 ($5853) relative to Cluster 2 ($6645; all p < 0.01; Fig. 6). In the post-index relative to the pre-index period, mean monthly costs remained on a higher trend in all clusters and were lower in Cluster 1 ($966) relative to Clusters 2 and 3 ($1627 and $1706; all p < 0.01), but similar in Clusters 2 and 3 (p = 0.30).

Distribution of care setting at index event and mean total healthcare costs, by care setting among patients with major depressive disorder with acute suicidal ideation or behavior (MDSI) [N = 38,876]. aTotal healthcare costs were reported in 2019 USD from the private payer’s perspective and included medical and pharmacy costs. bAmong patients with an inpatient place of service, the index event was defined as the duration of the inpatient stay. Among patients with an emergency room or outpatient visit, the index event was defined as the date of the visit. cCosts during the 12-month pre-index period were reported per-patient-per-month, and excluded costs associated with the index event. dAmong patients with an emergency room or outpatient place of service for the index event, costs represent total healthcare costs on the day of the visit. Among patients with an inpatient place of service for the index event, costs represent total healthcare costs associated with the admission. eCosts during the post-index period were reported per-patient per-month and excluded costs associated with the index event

Mean total healthcare costs, by cluster among patients with major depressive disorder with acute suicidal ideation or behavior (MDSI). aTotal healthcare costs were reported in 2019 USD from the private payer’s perspective and included medical and pharmacy costs. bCosts during the 12-month pre-index period were reported per-patient per-month, and excluded costs associated with the index event. cAmong patients with an emergency room or outpatient place of service for the index event, costs represent total healthcare costs on the day of the visit. Among patients with an inpatient place of service for the index event, costs represent total healthcare costs associated with the admission. dCosts during the post-index period were reported per-patient per-month and excluded costs associated with the index event. The mean duration of pre-index period is 8.3 months for the overall population, 8.4 months for cluster 1, 8.5 months for cluster 2, and 8.2 months for cluster 3

4 Discussion

A data-driven approach clustered patients with MDSI to identify different patient sub-types and understand their care pathways before and after the suicide-related event. The degree of pre-index exposure to the healthcare system was a key differentiator across clusters: patients in Cluster 1 were least exposed, patients in Cluster 2 were moderately exposed, and patients in Cluster 3 were most exposed. Involvement in care after the suicide-related event increased in all clusters, yet patients least exposed to the healthcare system before the event continued to receive the least amount of care after it.

Whether patients in Cluster 1 received less care pre-index, and especially post-index owing to being generally healthier or because of barriers in access to care is challenging to identify with claims data. Prior studies named certain clinical or sociodemographic characteristics, stigma, or availability of resources as barriers hindering access to adequate mental healthcare [7, 8, 15,16,17,18,19,20]. Being younger, with a lower prevalence of other mental and physical health conditions, patients in Cluster 1 might appear healthier and thus might receive less attention during all-cause outpatient visits pre-index, which the vast majority in this cluster had. Young men in particular are less likely to receive emotional health screening compared with young women [21], and the proportion of men was higher in Cluster 1 relative to other clusters. This may explain why Cluster 1 remained largely undiagnosed with MDD pre-index. Post-index, Cluster 1 had the lowest rate of suicidal ideation or behavior recurrence, suggesting this cluster might be less severe than others; this may reflect factors evident during evaluation and treatment but unobserved in claims. However, the relationship between the amount of care and the prevalence of coded recurrence post-index must be interpreted with caution, as few contacts with the healthcare system may reduce the likelihood of having a diagnosis for a recurrent event.

In the current study, pre-index, Cluster 2 was more exposed to mental healthcare than Cluster 1 and more exposed to antidepressant therapy then Clusters 1 and 3 but for the most part not diagnosed with MDD before the suicide-related event. For at least some of these patients, MDD might have been present but not diagnosed. As the majority in Cluster 2 pre-index had other mental health diagnoses and all patients used antidepressants, this cluster may also represent patients whose main diagnosis is not MDD, but who experience some symptoms consistent with MDD or have a primary diagnosis, for which antidepressants are still a mainstay of care (e.g., anxiety disorders). A decrease in the proportion of patients receiving antidepressants in this cluster after the suicide-related event may support this hypothesis, as the increased involvement with care may have led to a reconsideration of treatment plans for the underlying illness. However, other explanations may include a lack of antidepressant efficacy, issues related to tolerability, or problems with access to care providers. Patterns observed in Cluster 2 may highlight the need for careful patient evaluation and periodic revaluation to ensure critical symptoms are identified and treated in a timely manner, regardless of overarching diagnoses.

In all clusters, outpatient care for MDD was predominantly provided in a primary, rather than specialized care setting. Populations that have demonstrated acute, life-threatening mental health symptoms might receive greatest benefit from specialized care; however, this care is clearly not always offered or available.

After a suicide-related event, care continuity is critical. Suicide death rates following an initial psychiatric hospitalization were reported to be 300 times higher in the first week and 200 times higher in the first month compared with the global suicide rate [22]. Among those with a suicide-related event treated in an inpatient setting (56.9–63.7% across clusters in the current study), the suicide risk remains high up to 3 months following the discharge [23]. The current study revealed that although more patients in all clusters received mental health services after the suicide-related event, some did not. Across clusters, 11.8% (Cluster 3) to 20.7% (Cluster 1) had neither an MDD-related outpatient visits nor a visit for any specialized mental healthcare during the 30 days after the suicide-related event. Between 30.5% (Cluster 3) and 54.2% (Cluster 1) had no MDD-related outpatient visits during the same time. Notably, outpatient follow-up within 30 days of discharge after inpatient treatment for mental illnesses or intentional self-harm is a quality-of-care measure in the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set, a widely used performance improvement tool in the US healthcare system [24].

One of the contributions of this study is the quantification of costs among patients with MDD and a suicide-related event at various time periods, care settings for the suicide-related event, and in distinct clusters of patients. This information is limited in the literature and will be of value for payers and policy makers. Costs incurred after the suicide event remained on a higher trend compared with costs before the event, potentially indicating a persisting clinical worsening of symptoms following the suicide event or reflecting increased exposure to mental health services. Substantial costs of suicide-related events in inpatient or emergency room settings relative to costs of, predominantly, outpatient care before and after the event support the idea of early interventions with therapy to address the underlying psychiatric condition associated with suicidal behavior in at-risk individuals in an outpatient setting. This may result in improved clinical outcomes and economic gains if clinical worsening of MDD symptoms is avoided or mitigated.

Clusters in this study were obtained via hierarchical clustering. The utility of this approach for understanding heterogeneity in depressive disorders has been previously demonstrated [25, 26]. Prior studies similarly relied on pre-specified criteria to identify distinct clusters without making assumptions about the number of clusters present in the data. This study further contributes to the literature revealing the potential in data-driven mental health research.

In this study, before using the data-driven approach, authors attempted to cluster patients based on a clinical consensus only. Three characteristics were chosen to define subgroups: care setting at the index event (inpatient/ER/outpatient), timing of the first observed MDD diagnosis (at index/within 30 days pre-index/more than 30 days pre-index), and antidepressant use at index (none/monotherapy/augmentation therapy). Identifying similarities and differences across the resultant 27 unique combinations (clusters) was challenging, and distinct patterns were not apparent. Nonetheless, one interesting finding emerged from this exercise: patients who received care for the suicide-related event in different care settings (i.e., inpatient, ER, outpatient) generally appeared similar. This finding was confirmed by the data-driven approach. The data-driven approach to clustering revealed other distinct patterns of care pathways and thus provides an example of how the use of such methods may aid in exploring heterogeneity in patient populations.

4.1 Limitations

This study clustered patients based on administrative claims data; information on patient-reported or clinician-reported measures of severity or social determinants of health was unavailable. Suicide attempts and intentional self-harm in claims data may be underreported because of physician or patient concerns over stigma or liability or misclassification. As codes related to intentional self-harm do not distinguish between events intended to be fatal and events in which self-harm was intentional without the intent to die, patients identified using these codes required a confirmatory suicidal ideation diagnosis within 30 days. As such, results in this patient subset may not be generalizable to patients lost to follow-up early on.

Suicidal behavior may result in mortality. If patients lost to follow-up after the index event were more severe than those who continued to be observed, trends in resource use and costs post-index may be biased, and the direction of this bias may not be possible to predict. Nonetheless, the duration of follow-up was similar across clusters, which suggests that all clusters were similarly affected by this.

Antidepressant use may be misestimated as prescription fills do not account for medication dispensed being taken as prescribed, and out-of-pocket payment for some antidepressants is possible. Moreover, out-of-pocket payment is also a common practice for psychiatrist and psychotherapist visits in the USA [27], and these might be underreported. Finally, results might not be generalizable to the uninsured or those covered by plans other than commercial.

5 Conclusions

A data-driven approach revealed the heterogeneity in the level of involvement of patients with MDSI in mental healthcare before and after the suicide-related event. Patients least exposed to the healthcare system before the suicide event continued to receive less mental healthcare following the event. Continuity and quality of care among patients with MDSI must be ensured to mitigate the risk of poor outcomes. Future research should evaluate why some populations may be less engaged with mental healthcare and should examine the efficacy of interventions aimed to increase patients’ access and ability to receive mental health treatment.

References

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). National survey on drug use and health: key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States. 2019. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt29393/2019NSDUHFFRPDFWHTML/2019NSDUHFFR090120.htm#mde. Accessed 3 Mar 2021.

GBD 2017 Disease Injury Incidence Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–858. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7.

World Health Organization. Depression: key facts. 2020. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/. Accessed 7 Oct 2020.

American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. Third Edition. 2010. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf. Accessed 27 Jun 2018.

Kuvadia H, Wang K, Daly E, Voelker J, Pesa J, Connolly N, et al. National trends in the prevalence of major depressive disorder with suicidal ideation among adults using the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Annual Psych Congress; 30-6 Oct 2019; San Diego (CA).

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Borges G, Nock M, Wang PS. Trends in suicide ideation, plans, gestures, and attempts in the United States, 1990–1992 to 2001–2003. JAMA. 2005;293(20):2487–95.

Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Sampson NA, Jin R, Druss B, Wang PS, et al. Barriers to mental health treatment: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol Med. 2011;41(8):1751–61. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291710002291.

Chekroud AM, Foster D, Zheutlin AB, Gerhard DM, Roy B, Koutsouleris N, et al. Predicting barriers to treatment for depression in a U.S. national sample: a cross-sectional, proof-of-concept study. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(8):927–34. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800094.

Hedegaard H, Schoenbaum M, Claassen C, Crosby A, Holland K, Proescholdbell S. Issues in developing a surveillance case definition for nonfatal suicide attempt and intentional self-harm using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) coded data. Natl Health Stat Report. 2018;108:1–19.

Liao M, Li Y, Kianifard F, Obi E, Arcona S. Cluster analysis and its application to healthcare claims data: a study of end-stage renal disease patients who initiated hemodialysis. BMC Nephrol. 2016;17(1):25.

Ogbuabor G, Ugwoke F. Clustering algorithm for a healthcare dataset using silhouette score value. Int J Comput Sci Inform Technol. 2018;10(2):27–37.

Singh A, Yadav A, Rana A. K-means with three different distance metrics. Int J Comput Appl. 2013;67(10):13–7. https://doi.org/10.5120/11430-6785.

Huang Z. Extensions to the k-means algorithm for clustering large data sets with categorical values. Data Min Knowl Discov. 1998;2(3):283–304.

Rousseeuw PJ. Silhouettes: a graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. J Comput Appl Math. 1987;20:53–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-0427(87)90125-7.

Dew MA, Dunn LO, Bromet EJ, Schulberg HC. Factors affecting help-seeking during depression in a community sample. J Affect Disord. 1988;14(3):223–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-0327(88)90038-9.

Kessler RC, Zhao S, Katz SJ, Kouzis AC, Frank RG, Edlund M, et al. Past-year use of outpatient services for psychiatric problems in the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(1):115–23. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.156.1.115.

Walby FA, Myhre M, Kildahl AT. Contact with mental health services prior to suicide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatric Serv. 2018;69(7):751–9. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201700475.

Olfson M, Klerman GL. Depressive symptoms and mental health service utilization in a community sample. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1992;27(4):161–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00789000.

Blumenthal R, Endicott J. Barriers to seeking treatment for major depression. Depress Anxiety. 1996;4(6):273–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6394(1996)4:6%3c273::AID-DA3%3e3.0.CO;2-D.

Mojtabai R. Unmet need for treatment of major depression in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(3):297–305. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2009.60.3.297.

Committee on Improving the Health, Safety and Well-Being of Young Adults, Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Institute of Medicine; National Research Council. In: Bonnie RJ, Stroud C, Breiner H, editors. Investing in the health and well-being of young adults. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2015.

Chung D, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Wang M, Swaraj S, Olfson M, Large M. Meta-analysis of suicide rates in the first week and the first month after psychiatric hospitalisation. BMJ Open. 2019;9(3):e023883. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023883.

Walter F, Carr MJ, Mok PLH, Antonsen S, Pedersen CB, Appleby L, et al. Multiple adverse outcomes following first discharge from inpatient psychiatric care: a national cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(7):582–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30180-4.

National Committee for Quality Assurance. Follow-up after hospitalization for mental illness (FUH). New Delhi: National Committee for Quality Assurance; 2018.

Mitchell PB, Frankland A, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Roberts G, Corry J, Wright A, et al. Comparison of depressive episodes in bipolar disorder and in major depressive disorder within bipolar disorder pedigrees. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(4):303–9. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.088823.

Chekroud AM, Gueorguieva R, Krumholz HM, Trivedi MH, Krystal JH, McCarthy G. Reevaluating the efficacy and predictability of antidepressant treatments: a symptom clustering approach. JAMA Psychiat. 2017;74(4):370–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0025.

Pelech D, Hayford T. Medicare advantage and commercial prices for mental health services. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(2):262–7. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05226.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing assistance was provided by Loraine Georgy, PhD, an employee of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, which funded the development and conduct of this study and article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was supported by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. The sponsor was involved in the study design, interpretation of results, manuscript preparation, and publication decisions.

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

Jennifer Voelker, Abigail I. Nash, Kruti Joshi, and Cheryl Neslusan are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, and are stockholders of Johnson & Johnson. Maryia Zhdanava, Dominic Pilon, Tom Cornwall, Laura Morrison, Maude Vermette-Laforme, and Patrick Lefebvre are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, which funded the development and conduct of this study and article.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

The data that support the findings of this study are available from International Business Machines Corporation (IBM). Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Therefore, the data used in the study cannot be shared.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the following aspects of the research: the conception and design of the study, or analysis and interpretation of the data; drafting of the paper and revising it critically for intellectual content; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhdanava, M., Voelker, J., Pilon, D. et al. Cluster Analysis of Care Pathways in Adults with Major Depressive Disorder with Acute Suicidal Ideation or Behavior in the USA. PharmacoEconomics 39, 707–720 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-021-01042-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-021-01042-5