Abstract

Background and objectives

The dosing of cycloserine and terizidone is the same, as both drugs are considered equivalent or used interchangeably. Nevertheless, it is not certain from the literature that these drugs are interchangeable. Therefore, the amount of cycloserine resulting from the metabolism of terizidone and the relationship with hepatic function were determined.

Methods

This prospective clinical study involved 39 patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis admitted for an intensive phase of treatment. Cycloserine pharmacokinetic parameters for individual patients, like area under the curve (AUC), clearance (CLm/F), peak concentration (Cmax) and trough concentration (Cmin), were calculated from a previously validated joint population pharmacokinetic model of terizidone and cycloserine. Correlation and regression analyses were performed for pharmacokinetic parameters and unconjugated bilirubin (UB), conjugated bilirubin (CB), albumin, the ratio of aspartate transaminase to alanine aminotransferase (AST/ALT), or binding affinity of UB to albumin (Kaf), using R statistical software version 3.5.3.

Results

Thirty-eight patients took a daily dose of 750 mg terizidone, while one took 500 mg. The amount of cycloserine [median (range)] that emanated from terizidone metabolism was 51.6 (0.64–374) mg. Cmax (R2 = 22%, p = 0.003) and Cmin (R2 = 10.6%, p = 0.044) were significantly associated with increased CB concentration. Cmax was significantly associated with increased Kaf (R2 = 10.1%, p = 0.048), while high CLm/F was significantly associated with decreased AST/ALT (R2 = 21%, p = 0.003).

Conclusions

Cycloserine is not interchangeable with terizidone, as amounts are lower than expected. Cycloserine may be a predisposing factor to the development of hyperbilirubinaemia, as CLm/F is affected by hepatic function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Terizidone is not completely metabolised into cycloserine in patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis. |

Cycloserine and terizidone cannot be used interchangeably. |

Cycloserine and terizidone exposure may be a predisposing factor to the development of jaundice in patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis. |

1 Introduction

Drug-resistant tuberculosis remains a public health crisis, and treatment success continues to be low, at 55% worldwide [1]. Cycloserine is among the recommended group C second-line drugs for treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis [2]. One of its advantages is that it does not share cross-resistance with other anti-tuberculosis drugs in the regimen, although it is associated with neurological side effects [3]. Its antimycobacterial bacteriostatic effect is achieved through inhibition of the enzymes d-alanine ligase and alanine racemase, which are both essential for the biosynthesis of peptidoglycan, a bacterial cell wall component [4]. The susceptibility breakpoint is 64 µg/mL, and efficacy is driven by the percentage of time the plasma concentration is above the minimum inhibitory concentration. Nevertheless, the doses likely to achieve bactericidal effect in patients could be neurotoxic, as they are high [5].

Terizidone, which is a condensation product of two molecules of cycloserine joined by a terephthalaldehyde moiety, is also part of the recommended group C second-line drugs for treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis [2, 6]. The metabolism of terizidone has not been characterised. However, it is thought to convert into cycloserine and para-phthalate, likely by hydrolysis of imine groups pre-systemically [7, 8]. Terephthalaldehyde in humans has been shown to undergo quick metabolism into terephalic acid, which is a more stable metabolite and readily excreted in urine [9]. However, the enzymes involved in these metabolic processes are not known. The in vivo metabolism of cycloserine, a structural analogue of amino acid d-alanine [6], has not been characterised in humans. Meanwhile, in vitro studies show that d- or l-cycloserine in the presence of alanine racemase undergo racemisation followed by transamination to form a stable isoxazole by irreversible tautomerisation of the intermediate substrate, ketimine [10].

In patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis, a dose of 250–500 mg of cycloserine administered orally twice daily is slowly absorbed, with an absorption rate constant of 0.135 h−1, and reaches the average maximum plasma concentration of 22 µg/mL within 4 h [11]. It is widely distributed to most body fluids (bile, synovial fluid, breast milk, sputum) and tissues (lymphatic tissues and lungs) and crosses the placenta, with the apparent distribution of 10.5 L. Cycloserine apparent clearance is 1.38 L/h. It is primarily excreted in urine, with 50 and 70% excreted unchanged in 12 and 24 h, respectively. The elimination half-life is 5.27 h. The between-subject variation in apparent clearance and distribution volume is 22.3 and 35.1%, respectively [11, 12].

Treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis with a multidrug regimen consisting of cycloserine/terizidone and other second-line drugs is associated with adverse reactions [13]. Hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity and hypokalaemia are the most possible life-threatening adverse reactions that require alteration of the drug regimen or temporal withdraw [14]. Furthermore, mortality is high when hepatotoxicity is accompanied by jaundice, encephalopathy and ascites [15].

Cycloserine and terizidone are considered equivalent, and doses are currently used interchangeably [7, 8]. Owing to the unavailability of bioequivalence or mass balance studies of terizidone, the equivalence of dosing has not yet been established [8]. The objective of this study was to determine the average amount of cycloserine that results from the metabolism of terizidone in patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis. We also assessed the potential effect of cycloserine and terizidone exposure on the incidence of hepatotoxicity or nephrotoxicity in these patients.

2 Methods

The details of the study design, including the study population, drug administration, ethics, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and population pharmacokinetic modelling, have been described elsewhere [16]. Briefly, this was a prospective clinical study of patients admitted for intensive phase treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis. They were taking 500–750 mg of terizidone once daily, and other second-line anti-tuberculosis drugs (ethionamide, pyrazinamide, moxifloxacin, ethambutol, isoniazid and kanamycin) were administered according to the local treatment guideline [17]. Blood for pharmacokinetics study was sampled at baseline and 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 3.5, 4, 8, 16 and 24 h after drug administration. Separate blood samples were also drawn for liver [total bilirubin, conjugated bilirubin, unconjugated bilirubin, albumin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST)] and renal function markers (serum creatinine). Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) [18] and creatinine clearance (CrCL) [19] were calculated, and demographic information including HIV status was obtained from each patient.

2.1 Determination of Cycloserine and Terizidone in Plasma

Cycloserine concentration in plasma was determined using an ultra-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry method. Methanol was used to extract cycloserine and propranolol (internal standard) from plasma by a protein precipitation method. Acidified acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid was used as the mobile phase, and chromatographic separation was achieved on a Phenomenex PFP reversed phase column. The lower limit of quantification and limit of detection were 0.01 μg/mL and 0.004 μg/mL, respectively. The average intra-day precision was 10.2%, while inter-day was 7.3%. Accuracy ranged between 98.7 and 117.3%, and the coefficient of determination was 0.9994. Cycloserine was stable after three freeze–thaw cycles, and extraction efficiency was in the range 88.7–91.2% [20]. Terizidone was analysed using a high-performance liquid chromatography with UV detector (HPLC-UV) method. The within- and between-run accuracy was in the range 99.7–112.7% and 100.5–107.4%, respectively. The intra- and inter-day precision, measured as percentage relative standard deviation, ranged between 0.35 and 9.4% and 1.48 and 6.79%, respectively. The lower limit of quantification was 3.125 µg/mL, while the limit of detection was 0.78 µg/mL. The coefficient of determination value ranged between 0.9988 and 0.9999, and calibration curves were linear [21].

2.2 Pharmacokinetic Modelling

The concentration–time profiles of terizidone and its metabolite cycloserine were jointly modelled using non-linear mixed effects implemented in Monolix 2018R1 software [22]. The final joint model without covariates was used to estimate the biotransformation rate constant (ktr) describing the metabolism of terizidone into cycloserine and cycloserine clearance (CLm/F). The model and the validation details have been described elsewhere [16].

2.3 Calculation of the Amount of Cycloserine and Other Pharmacokinetic Parameters

The following formulae were coded and added to the Monolix MLXTRAN model script of the final joint model for the computation of parameters. The amount of cycloserine was calculated as shown in Eq. (1):

where dose is the amount of cycloserine, AUC is the area under the concentration–time profile of cycloserine from 0 to 24 h, and CLm/F is the apparent clearance of cycloserine.

The AUC was calculated by integrating the concentration from 0 to 24 h according to Eq. (2):

where C is cycloserine concentration.

Cycloserine half-life was calculated according to Eq. (3):

where \({\text{ke}} = ({\text{Clm/F}})/10.5.\)

The distribution volume of cycloserine was fixed to a literature value of 10.5 L [11] when estimating CLm/F. This was done in order to overcome the non-identifiability parameter problem encountered in parent–metabolite pharmacokinetic models of orally administered drugs [23].

The biotransformation half-life was calculated as shown in Eq. (4):

The peak (Cmax) and trough (Cmin) concentrations were obtained from the observed data for both cycloserine and terizidone concentration–time profiles. The individual predicted values for terizidone clearance due to biotransformation (CLtm/F) and other routes (CLto/F) were computed in Monolix and extracted from the output file.

2.4 Calculation of Binding Affinity of Unconjugated Bilirubin to Albumin and AST/ALT Ratio

The strength of unconjugated bilirubin binding to albumin was calculated according to Eq. (5) [24]:

where Kaf is the binding affinity, with the units L/µmol, and TB and UB are total bilirubin and unconjugated bilirubin, respectively. The AST/ALT ratio [25], a marker reflecting alterations in hepatic function, was calculated by dividing the AST value by the ALT value for each patient.

2.5 Statistical Analysis

Mann–Whitney U test was performed to determine differences in the demographic information stratified by HIV status. We performed Spearman’s correlations between hepatic or renal function (eGFR/CrCL) markers and pharmacokinetic parameters (Cmin, Cmax, CLm/F, CLtm/F and CLto/F). This was done in order to determine whether a statistically significant linear relationship existed, as cycloserine or terizidone could bind to albumin or affect the binding affinity of unconjugated bilirubin to albumin. Furthermore, cycloserine concentration may be affected by alterations in hepatic or renal function. If the correlations were significant, linear stepwise regression analysis was performed in order to determine if pharmacokinetic parameters were significantly predicting hepatic or renal function markers. A two-tailed p value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The analysis was performed in the R version 3.5.3 statistical environment [26].

3 Results

Thirty-nine drug-resistant tuberculosis patients (20 females and 19 males) participated in this study. Out of the seven patients with comorbidities, three had cryptococcal meningitis, while each of the remaining four had deep venous thrombosis, hyperlipidaemia, gastric acid or epilepsy. Thirty-eight out of 39 patients took a daily dose of 750 mg terizidone, while one patient took 500 mg. Table 1 shows the summary of demographic information. The HIV-infected patients had significantly lower albumin than their HIV-uninfected counterparts (30 vs. 35.5 g/L; p = 0.041). However, the rest of the demographic variables were similar in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected groups.

3.1 Amount of Cycloserine and Pharmacokinetic Parameters

The summary of the calculated amount of cycloserine or dose resulting from terizidone metabolism and the values for pharmacokinetic parameters is shown in Table 2. There was wide variation in cycloserine dose and also in the pharmacokinetic parameters, except for cycloserine half-life, for which the variation was relatively narrow. Table 3 shows the summary of terizidone pharmacokinetic parameters.

3.2 Correlations Between Hepatic Function Markers and Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Cycloserine and Terizidone

Significant positive correlations existed between AST, ALT, conjugated bilirubin, Kaf and cycloserine pharmacokinetic parameters (Cmin, Cmax or CLm/F), as shown in Table 4. There was significant negative correlation between AST/ALT ratio and CLm/F (p = 0.016). Meanwhile, there was no significant correlation between albumin or unconjugated bilirubin and the pharmacokinetic parameters (p > 0.05). Similarly, no significant correlations existed between renal function markers (CrCL and eGFR) and CLm/F (p > 0.05). Significant positive correlations existed between terizidone Cmax and conjugated or unconjugated bilirubin (p = 0.038 and 0.02, respectively), as shown in Table 5.

3.3 Pharmacokinetic Parameters Predictive of Hepatic Function Markers

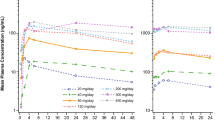

The cycloserine Cmax was found to be a significant predictor of both conjugated bilirubin and Kaf, as shown by regression plots b and c of Fig. 1. The associations were in such a way that an increase in Cmax resulted in a significant increase in conjugated bilirubin and Kaf (plot b, β = 0.06, R2 = 22% and p = 0.003; plot c, β = 2.3, R2 = 10.1% and p = 0.048). Cmin could not significantly predict Kaf in the regression analysis, although a significant correlation existed between Cmin and Kaf in correlation analysis. Meanwhile, increase in Cmin was significantly associated with an increase in conjugated bilirubin (plot a, β = 0.1, R2 = 10.6% and p = 0.044). The CLm/F significantly predicted AST/ALT ratio, as shown in plot d of Fig. 1. Increase in CLm/F was significantly associated with a decrease in AST/ALT ratio (β = − 0.2, R2 = 21% and p = 0.003). Terizidone Cmax significantly predicted concentration of conjugated bilirubin (β = 0.008, R2 = 14.2% and p = 0.018) as well as unconjugated bilirubin (β = 0.012, R2 = 11.4% and p = 0.035). The regression plot is shown in Fig. 2.

4 Discussion

This study aimed to determine the amount of cycloserine that results from the metabolism of terizidone and the relationship between cycloserine exposure parameters and hepatic or renal function markers in patients receiving treatment for drug-resistant tuberculosis. There appears to be no studies in the literature that have quantified the amount of cycloserine as a terizidone metabolite in drug-resistant tuberculosis patients. Terizidone is thought to undergo complete hydrolysis into cycloserine pre-systemically [7]. Since one mole of terizidone has two moles of cycloserine and a mole of terephthalaldehyde moiety, it is expected for a 750-mg daily dose of terizidone to produce 507 mg of cycloserine, with an assumption that bioavailability is near 100%. In the current study, the median dose of cycloserine produced from a 750-mg dose of terizidone was 51.6 mg, which was lower than expected. This observation clearly suggests that terizidone is not completely hydrolysed to cycloserine pre-systemically. Furthermore, terizidone was detected systemically over a period of 24 h after its administration, and on average, only 29% of the total dose was metabolised to cycloserine [16]. The clinical implication of this finding in the current study is that cycloserine and terizidone should not be used interchangeably, as exposure parameters (Cmax, Cmin and AUC) may be significantly lower in patients taking terizidone than those taking cycloserine. Owing to the low amount of cycloserine produced from terizidone, dose optimisation or therapeutic drug monitoring, contrary to what some authors imply [27], should be based on terizidone and not cycloserine concentration. Additionally, in patients treated with terizidone, Court et al. [28] reported higher cycloserine Cmax than in the current study. The difference could have been that in the Court et al. study [28], there were patients who had renal insufficiency, which could have led to accumulation of cycloserine, as it primarily undergoes renal elimination [6]. Furthermore, the bioavailability and biotransformation rate of terizidone into cycloserine in the current study could have been lower than in the Court et al. [28] study. We cannot overlook the possibility of pharmacokinetic interactions with co-administered drugs in the current study.

Bilirubin, a pigment derived from the breakdown of haemoglobin, increases in blood because of an imbalance between its production and excretion. Since unconjugated bilirubin is not water soluble, it is bound to albumin and transported to the liver, where it is made soluble or conjugated with glucuronic acid and subsequently undergoes biliary excretion into the gastrointestinal tract [29]. Increased serum levels of conjugated bilirubin are an indication of hepatic dysfunction or liver disease, clinically manifested as jaundice [25]. In the current study, cycloserine Cmin and Cmax as well as terizidone Cmax were significantly associated with increased concentration of conjugated bilirubin.

Although the concentration of conjugated bilirubin in most of the patients was within the normal range, this observation implies that high plasma cycloserine or terizidone concentrations may be associated with hyperbilirubinaemia in some patients.

Unconjugated bilirubin is insoluble in water and hence cannot be excreted via the kidney. It is instead bound to albumin and transported to the liver for conjugation. Increased serum levels of unconjugated bilirubin indicate that there is an accumulation in the bloodstream due to haemolysis, which may be caused by haemolytic anaemia, hepatocellular dysfunction (e.g. hepatitis) and cirrhosis in which the excretory function of the hepatocytes is impaired [25]. Some drugs have been shown to compete with unconjugated bilirubin for binding to albumin, which leads to increased concentration of unconjugated bilirubin and causes encephalopathy in neonates [30,31,32,33]. Therefore, the binding affinity of unconjugated bilirubin to albumin is of clinical importance. Cycloserine Cmax in the current study was associated with increased Kaf, while Cmin results were insignificant. This means that high cycloserine concentrations improve the binding affinity of unconjugated bilirubin to albumin, which is potentially a desired characteristic in bilirubin metabolism. The observed relationship between Kaf and Cmax may also imply that cycloserine is less bound to albumin.

The AST/ALT ratio is a non-invasive diagnostic index used to predict liver cirrhosis or fibrosis, and a value higher than 1 is indicative of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [34, 35]. Cycloserine is primarily renally cleared, with 70% excreted unchanged [12], while the other portion is metabolised in the liver. However, the enzymes specifically involved in the catabolism of cycloserine in vivo are not known. In the current study, higher CLm/F was significantly associated with low AST/ALT ratio. Additionally, the median value of the AST/ALT ratio was more than 2. This was an obvious indication that liver disease affects hepatic function, which leads to low activity or production of cycloserine-metabolising enzymes and eventually results in low CLm/F. Meanwhile, the non-correlation between CLm/F and CrCL or eGFR in the current study was unexpected, as cycloserine is also cleared via the renal route. This observation could suggest a possibility of more cycloserine undergoing active tubular secretion than glomerular filtration, as seen in other drugs [36].

This study has some limitations to consider. In vitro drug plasma binding studies were not performed due to ethical issues as we were supposed to use drug-free human plasma. Cycloserine metabolites were not measured in plasma; this could have helped to determine the rate of cycloserine metabolism in vivo. Furthermore, cycloserine was not measured in patients’ urine for determination of the fraction of the dose that is excreted unchanged. We only measured cycloserine and terizidone in plasma. Since patients were on a multidrug treatment regimen, other anti-tuberculosis drugs could have shown similar results as cycloserine and terizidone. The study, however, is important as it gives an insight into how cycloserine and terizidone exposure might affect hepatic function. This can guide the clinical decision regarding whether or not to withdraw terizidone in the case of hepatotoxicity.

5 Conclusions

In conclusion, the amount of cycloserine resulting from the metabolism of terizidone in drug-resistant tuberculosis patients was lower than expected. High concentrations of cycloserine could potentially favour bilirubin disposition, albeit be a predisposing factor to the development of jaundice in drug-resistant tuberculosis patients taking terizidone. Cycloserine clearance is reduced in hepatic dysfunction.

References

World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization Press; 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/274453/9789241565646-eng.pdf. Accessed 11 Jan 2019.

World Health Organization. WHO treatment guidelines for drug-resistant tuberculosis 2016 update. Geneva: World Health Organization Press; 2016. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/250125/1/9789241549639-eng.pdf. Accessed 12 Dec 2018.

World Health Organization. Companion handbook to the WHO guidelines for the programmatic management of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Geneva: World Health Organization Press; 2014. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/130918/9789241548809_eng.pdf. Accessed 14 Nov 2018.

Di Perri G, Bonora S. Which agents should we use for the treatment of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54:593–602.

Deshpande D, Alffenaar JWC, Köser CU, Dheda K, Chapagain ML, Simbar N, et al. d-Cycloserine pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics, susceptibility, and dosing implications in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: a Faustian deal. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67:S308–16.

Trnka L, Mison P, Bartmann K, Otten H. Experimental evaluation of efficacy. In: Bartmann K, editor. Antituberculosis drugs. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media; 2013. p. 31–164.

World Health Organization. Notes on the design of bioequivalence study: terizidone. Geneva: World Health Organization Press; 2015. https://extranet.who.int/prequal/sites/default/files/documents/29%20BE%20terizidone_Oct2015_0.pdf. Accessed 10 June 2018.

World Health Organization. Technical report on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics (PK/PD) of medicines used in the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Geneva: World Health Organization Press; 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/260440/WHO-CDS-TB-2018.6-eng.pdf. Accessed 10 Jan 2018.

Yuan G, Xu J, Qu T, Wang B, Zhang R, Wei C, et al. Metabolism and disposition of tribendimidine and its metabolites in healthy Chinese volunteers. Drugs R D. 2010;10:83–90.

Fenn TD, Stamper GF, Morollo AA, Ringe D. A side reaction of alanine racemase: transamination of cycloserine. Biochemistry. 2003;42:5775–83.

Chang MJ, Jin B, Chae JW, Yun HY, Kim ES, Lee YJ, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of moxifloxacin, cycloserine, p-aminosalicylic acid and kanamycin for the treatment of multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017;49:677–87.

Brennan PJ, Young DB, Robertson BD. Handbook of anti-tuberculosis agents. Tuberculosis. 2008;88:85–170.

Shin SS, Pasechnikov AD, Gelmanova IY, Peremitin GG, Strelis AK, Mishustin S, et al. Treatment outcomes in an integrated civilian and prison MDR-TB treatment program in Russia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10:402–8.

Keshavjee S, Gelmanova IY, Shin SS, Mishustin SP, Andreev YG, Atwood S, et al. Hepatotoxicity during treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: occurrence, management and outcome. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:596–603.

Devarbhavi H, Singh R, Patil M, Sheth K, Adarsh CK, Balaraju G. Outcome and determinants of mortality in 269 patients with combination anti-tuberculosis drug-induced liver injury. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:161–7.

Mulubwa M, Mugabo P. Steady state population pharmacokinetics of terizidone and its metabolite cycloserine in patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.13975.

Department of Health. Management of drug-resistant tuberculosis: policy guidelines. Pretoria, South Africa: Department of Health, Republic of South Africa; 2013. https://www.health-e.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/MDR-TB-Clinical-Guidelines-Updated-Jan-2013.pdf. Accessed 23 Mar 2018.

Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, Marsh J, Stevens LA, Kusek JW, et al. Expressing the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate with standardized serum creatinine values. Clin Chem. 2007;53:766–72.

Cockcroft DW, Gault H. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16:31–41.

Mulubwa M, Mugabo P. Sensitive ultra-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry method for determination of cycloserine in plasma for a pharmacokinetics study. J Chromatogr Sci. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/chromsci/bmz028.

Mulubwa M, Mugabo P. Analysis of terizidone in plasma using HPLC-UV method and its application in pharmacokinetic study of patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis. Biomed Chromatogr. 2018;32:e4325.

Monolix Version 2018R1. Antony, France: Lixoft SAS; 2018. http://lixoft.com/products/monolix/. Accessed 4 Feb 2019.

Duffull SB, Chabaud S, Nony P, Laveille C, Girard P, Aarons L. A pharmacokinetic simulation model for ivabradine in healthy volunteers. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2000;10:285–94.

Amin SB. Bilirubin binding capacity in the preterm neonate. Clin Perinatol. 2016;43:241–57.

Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Jameson LJ, Hauser SL, Loscalzo J. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. 20th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc; 2018.

R Core Team. The R project for statistical computing; 2019. https://www.r-project.org/. Accessed 26 Apr 2019.

Alffenaar JWC, Peloquin CA, Migliori GB. Making optimal use of available anti-tuberculosis drugs: first steps to investigate terizidone. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2018;22:2.

Court R, Wiesner L, Stewart A, de Vries N, Harding J, Maartens G, et al. Steady state pharmacokinetics of cycloserine in patients on terizidone for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2018;22:30–3.

Kamisako T, Kobayashi Y, Takeuchi K, Ishihara T, Higuchi K, Tanaka Y, et al. Recent advances in bilirubin metabolism research: the molecular mechanism of hepatocyte bilirubin transport and its clinical relevance. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:659–64.

Cooper-Peel C, Brodersen R, Robertson A. Does ibuprofen affect bilirubin–albumin binding in newborn infant serum? Pharmacol Toxicol. 1996;79:297–9.

Brodersen R. Competitive binding of bilirubin and drugs to human serum albumin studied by enzymatic oxidation. J Clin Investig. 1974;54:1353–64.

Martin E, Fanconi A, Kälin P, Zwingelstein C, Crevoisier C, Ruch W, et al. Ceftriaxone-bilirubin-albumin interactions in the neonate: an in vivo study. Eur J Pediatr. 1993;152:530–4.

Wennberg RP, Rasmussen LF, Ahlfors CE. Displacement of bilirubin from human albumin by three diuretics. J Pediatr. 1977;90:647–50.

Alexopoulou A, Pouriki S, Vasilieva L, Alexopoulos T, Filaditaki V, Gioka M, et al. Evaluation of noninvasive markers for the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis liver disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:1547–52.

Angulo P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1221–31.

Odlind B, Beermann B. Renal tubular secretion and effects of furosemide. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1980;27:784–90.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Brewelskloof Hospital authorities and the Department of Health, Province of the Western Cape for granting permission to conduct the study. We wish to thank the patients for their willingness to participate in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The South African Medical Research Council, National Research Foundation (Grant no. SFH150628121613) and the University of the Western Cape supported this research project financially.

Conflict of interest

The authors, Mwila Mulubwa and Pierre Mugabo, declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of the Western Cape (Ref: 07/6/12) and the University of Cape Town (Ref: 777/2014). The study was conducted according to the principles outlined in the declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Mulubwa, M., Mugabo, P. Amount of Cycloserine Emanating from Terizidone Metabolism and Relationship with Hepatic Function in Patients with Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis. Drugs R D 19, 289–296 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40268-019-00281-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40268-019-00281-4