Abstract

Background and Objective

Real-world evidence studies of brivaracetam (BRV) have been restricted in scope, location, and patient numbers. The objective of this pooled analysis was to assess effectiveness and tolerability of brivaracetam (BRV) in routine practice in a large international population.

Methods

EXPERIENCE/EPD332 was a pooled analysis of individual patient records from multiple independent non-interventional studies of patients with epilepsy initiating BRV in Australia, Europe, and the United States. Eligible study cohorts were identified via a literature review and engagement with country lead investigators, clinical experts, and local UCB Pharma scientific/medical teams. Included patients initiated BRV no earlier than January 2016 and no later than December 2019, and had ≥ 6 months of follow-up data. The databases for each cohort were reformatted and standardised to ensure information collected was consistent. Outcomes included ≥ 50% reduction from baseline in seizure frequency, seizure freedom (no seizures within 3 months before timepoint), continuous seizure freedom (no seizures from baseline), BRV discontinuation, and treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) at 3, 6, and 12 months. Patients with missing data after BRV discontinuation were considered non-responders/not seizure free. Analyses were performed for all adult patients (≥ 16 years), and for subgroups by seizure type recorded at baseline; by number of prior antiseizure medications (ASMs) at index; by use of BRV as monotherapy versus polytherapy at index; for patients who switched from levetiracetam to BRV versus patients who switched from other ASMs to BRV; and for patients with focal-onset seizures and a BRV dose of ≤ 200 mg/day used as add-on at index. Analysis populations included the full analysis set (FAS; all patients who received at least one BRV dose and had seizure type and age documented at baseline) and the modified FAS (all FAS patients who had at least one seizure recorded during baseline). The FAS was used for all outcomes other than ≥ 50% seizure reduction. All outcomes were summarised using descriptive statistics.

Results

Analyses included 1644 adults. At baseline, 72.0% were 16–49 years of age and 92.2% had focal-onset seizures. Patients had a median (Q1, Q3) of 5.0 (2.0, 8.0) prior antiseizure medications at index. At 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively, ≥ 50% seizure reduction was achieved by 32.1% (n = 619), 36.7% (n = 867), and 36.9% (n = 822) of patients; seizure freedom rates were 22.4% (n = 923), 17.9% (n = 1165), and 14.9% (n = 1111); and continuous seizure freedom rates were 22.4% (n = 923), 15.7% (n = 1165), and 11.7% (n = 1111). During the whole study follow-up, 551/1639 (33.6%) patients discontinued BRV. TEAEs since prior visit were reported in 25.6% (n = 1542), 14.2% (n = 1376), and 9.3% (n = 1232) of patients at 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively.

Conclusions

This pooled analysis using data from a variety of real-world settings suggests BRV is effective and well tolerated in routine clinical practice in a highly drug-resistant patient population.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This large, international pooled analysis shows that brivaracetam (BRV) is effective and well tolerated in patients with epilepsy in the real world. |

The patient population was highly drug-resistant, evidenced by the median number of prior and concomitant antiseizure medications (ASMs) at index (5.0 and 2.0, respectively). |

The pooled analysis summarised existing real-world data from different countries across specific patient groups (including patients with different seizure types, on monotherapy, and switching to BRV from other ASMs, including levetiracetam) to provide additional evidence that BRV is effective and well tolerated among these subgroups of patients. |

1 Introduction

Brivaracetam (BRV) is a third‐generation antiseizure medication (ASM) that acts as a selective ligand for synaptic vesicle protein 2A, a presynaptic membrane glycoprotein implicated in modulation of synaptic vesicle exocytosis and neurotransmitter release [1]. BRV is approved in over 50 countries as a treatment for focal-onset (partial-onset) seizures with or without secondary generalisation. Adjunctive or monotherapy indication, approved age range, and formulations vary depending on country.

The efficacy and tolerability of BRV for adjunctive treatment of focal-onset seizures in patients ≥ 16 years of age were established in three phase III, randomised, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose trials [2,3,4]. Clinically relevant seizure freedom and reductions in seizure frequency, with a low incidence of adverse events (AEs) and low discontinuation rates due to AEs, were observed with BRV doses of 50–200 mg/day. To date, real-world evidence studies of BRV have been restricted in scope, location, and patient numbers. Therefore, the objective of this pooled analysis was to summarise existing real-world data on BRV response and tolerability across specific patient groups, using individual patient records from non-interventional studies in different countries. This analysis pooled data from several retrospective studies (some unpublished) that adhered to individual study protocols.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design and Patient Population

EXPERIENCE/EPD332 was a pooled analysis of individual patient records from multiple independent non-interventional, retrospective studies that used clinical chart review cohorts of patients who initiated BRV in clinical practice. Data were collected from studies conducted in epilepsy centres or hospitals in Australia, Europe, and the United States, which had previously defined cohorts of patients with extracted follow-up data. A critical review of the literature and engagement with country lead investigators, clinical experts, and local UCB Pharma scientific and medical teams identified BRV cohorts that met the inclusion criteria (Table S1, see electronic supplementary material [ESM]).

Patients received BRV as prescribed by their treating physician, and according to standard clinical practice in their region. The date of BRV availability in each country marked the beginning of patient enrolment; patients must have initiated BRV no earlier than January 2016 and no later than December 2019. Patients had ≥ 6 months of follow-up data from the index date (date of BRV initiation; Fig. S1, see ESM). The follow-up period for each patient was 12 months after the index date or until one of the following events occurred: BRV discontinuation, death, disenrolment due to any reason, 365 days of follow-up, or end of the study period. Per the individual retrospective study protocols, some data may not adhere exactly to the criteria described above (i.e., few patients had a follow-up > 12 months and the follow-up period for several cohorts was < 12 months). To ensure that the information recorded was consistent for all cohorts, the databases from each of the non-interventional studies were reformatted and standardised.

Baseline characteristics were assessed at the index date for each patient. Historical variables may have been collected at any point before or at index date. As this analysis included pooled medical chart review data, items from common epilepsy patient intake questions were selected, whether or not the physician had access to a complete patient medical record before initiating care. The terminology used for seizure types is consistent with the terminology used in the original studies, many of which predated the publication of the 2017 operational classification of seizure types by the International League Against Epilepsy [5].

This pooled analysis followed the 2005 Food and Drug Administration’s Guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices (GPP) and the 2008 International Society of Pharmacoepidemiology Guidelines for GPP. Patient data were de-identified before being processed. No ethics committee approval was required for the EXPERIENCE database given that it consisted of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) compliant anonymised data. However, the Australian (AUS) and United States of America (USA) cohorts received ethics approval to release their data for inclusion in the EXPERIENCE database. Each non-interventional study that was included in EXPERIENCE received appropriate ethics and/or scientific review board approval as part of the initial study proposal at each institution.

2.2 Outcomes

Effectiveness was evaluated at 3, 6, and 12 months after index date by assessing the following outcomes: seizure reduction, defined as ≥ 50% reduction from baseline in seizure frequency; seizure freedom, defined as no seizures within 3 months prior to the timepoint (note: some cohorts defined seizure freedom as no seizure since the prior visit); continuous seizure freedom, defined as no seizures reported for any timepoint after baseline; and BRV retention, defined as the number of patients who remained on BRV at each timepoint. Patients who discontinued BRV were considered to have 'no seizure reduction' (for ≥ 50% seizure reduction), and 'no seizure freedom' (for seizure freedom and continuous seizure freedom) at the time of discontinuation and onwards (Fig. S2, see ESM). Safety and tolerability outcomes were as follows: BRV discontinuation due to tolerability reasons (defined as the number of patients who discontinued BRV due to tolerability since prior visit); incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) since prior visit; severity of TEAEs; and incidence of psychiatric, cognitive, and behavioural TEAEs.

2.3 Patient Subgroups

Outcomes were assessed for all adult patients (≥ 16 years) and for patient subgroups. Subgroup analyses included assessments by seizure type recorded at baseline: focal-onset seizures without secondary generalisation; focal-onset seizures with secondary generalisation; and generalised-onset seizures (more than one seizure type could have been recorded). Patients with focal-onset seizures with undocumented subtype (i.e., with or without secondary generalisation) were deemed to have secondarily generalised seizures. Subgroup analyses were also performed by number of prior ASMs at index (ASMs used and stopped before BRV initiation); by use of BRV as monotherapy (no concomitant ASMs at index) versus polytherapy (concomitant ASMs at index); for patients who switched from levetiracetam (LEV) to BRV at index versus patients who switched from other ASMs (not including LEV) to BRV (patients may have taken LEV historically but stopped LEV treatment long before BRV initiation); and for patients with focal-onset seizures and a BRV dose of ≤ 200 mg/day used as add-on at index.

2.4 Statistical Analyses

Analysis populations included the full analysis set (FAS; all patients who received at least one dose of BRV and had seizure type and age documented at baseline) and the modified FAS (mFAS; all patients in the FAS who had at least one seizure recorded during baseline). With the exception of seizure reduction, all follow-up outcomes were analysed using data from the FAS based on the estimand at each timepoint. It was necessary to use the mFAS for ≥ 50% seizure reduction, as a baseline seizure assessment is required to calculate reduction in seizures. Assessments of seizure reduction, seizure freedom, and continuous seizure freedom in the overall population and in all patient subgroups (including subgroups by seizure type at baseline) included all seizures recorded during follow-up. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to analyse the time to BRV discontinuation. Patients were censored at death, disenrolment, or end of the study period, whichever occurred first. All outcomes were summarised using descriptive statistics, and no measures were taken to impute or replace missing data. Percentages were based on the number of patients analysed. Analyses were performed using SAS® (Statistical Analysis System) version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

3 Results

3.1 Patient Cohorts

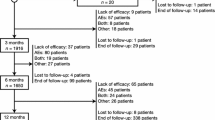

Data from 1976 patients from five countries (Spain, Germany, Australia, USA, and UK) were identified and made available to the EXPERIENCE pooled analysis (Fig. S3, see ESM). This included eight adult cohorts (Spain [SP] 1 [6], SP2 [7], SP3 [8], Germany [GER] [9, 10], GER1 [11, 12], AUS [13], USA [data from the University of Alabama at Birmingham Epilepsy Center only; unpublished data], and United Kingdom [UK] [14]), and one paediatric cohort (SP4 [15]). A total of 1716 adult patients (≥ 16 years of age) from cohorts SP1 (N = 544), SP2 (N = 72), SP3 (N = 196), GER (N = 275), GER1 (N = 213), AUS (N = 291), and USA (N = 125) remained after excluding the paediatric cohort (SP4, N = 66; analysed separately, with data reported elsewhere [16]), 64 patients for whom either age or seizure type was not documented, nine paediatric patients within the adult cohorts, and the UK cohort (N = 121), which did not meet eligibility criteria (patients with < 6 months of BRV exposure were excluded). The SP2 cohort was excluded from most analyses, as no data were collected for seizure assessments (≥ 50% seizure reduction, seizure freedom, and continuous seizure freedom) and TEAEs at 3, 6, and 12 months, and patients with focal-onset seizures were underrepresented (33.3% of cohort). Therefore, the analysable adult data set included 1644 patients (FAS). The SP3 cohort was excluded from the mFAS (analyses of ≥ 50% seizure reduction) because seizure frequency at baseline was not collected for these patients.

3.2 Overall Population

A total of 1644 patients ≥ 16 years of age from Spain (n = 740), Germany (n = 488), Australia (n = 291), and the USA (n = 125) received at least one dose of BRV, had seizure type and age documented at baseline, and were included in the FAS (Table 1). Of these, 1293 patients had at least one seizure recorded during baseline and were included in the mFAS.

At baseline, 51.9% of patients in the FAS (n = 1644) were female, and most (72.0%) were between 16 and 49 years of age (Table 1). Patients had a median (Q1, Q3) time since first diagnosis of 18.0 (8.0, 30.0) years; 92.2% had focal-onset seizures and 7.7% had generalised-onset seizures. Patients had a median (Q1, Q3) of 5.0 (2.0, 8.0) prior ASMs at index and 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) concomitant maintenance ASMs at index.

The median (Q1, Q3) duration of exposure to BRV was 345.5 (131.5, 410.9) days, with 630 (38.7%) patients exposed for > 365 days (n = 1629; FAS). The median BRV dose was 100.0 mg/day at index and 200.0 mg/day at 12 months (Table S2, see ESM). Overall, 551/1639 (33.6%) patients discontinued BRV during the whole study follow-up (Table S3, see ESM); 173/1629 (10.6%) discontinued in the first 3 months, 156/1629 (9.6%) between 3 and 6 months, and 141/1629 (8.7%) between 6 and 12 months. Of patients with a documented reason for BRV discontinuation (n = 545), 44.6%, 35.0%, and 13.4% discontinued due to lack of effectiveness, tolerability, and lack of effectiveness and tolerability, respectively (reasons were not mutually exclusive).

A ≥ 50% seizure reduction was achieved by 32.1%, 36.7%, and 36.9% of patients at 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively (mFAS; Fig. 1a); seizure freedom was 22.4%, 17.9%, and 14.9% (FAS: Fig. 1b); and continuous seizure freedom was 22.4%, 15.7%, and 11.7% (FAS; Fig. 1c). BRV retention was 89.4%, 79.8%, and 71.1% at 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively (FAS; Fig. 1d). The Kaplan–Meier curve for treatment retention showed that 50% of patients remained on BRV at 1464 days since BRV initiation (FAS; Fig. 2).

Analyses of effectiveness for the overall population. n represents the number of patients with data for the reported variable at each visit. Patients with missing data were excluded from all seizure analyses. Patients with missing data after BRV discontinuation were considered non-responders and not seizure free. BRV brivaracetam, FAS full analysis set, mFAS modified full analysis set

Kaplan–Meier estimated time to discontinuation of BRV (FAS). The median survival days (product-limit median) represent the number of days after which < 50% of the population will remain on BRV. Patients who did not discontinue BRV were censored at the end of follow-up. The SP2 cohort was excluded from the BRV retention analysis, as the analysis was not stratified by seizure type at baseline. BRV brivaracetam, FAS full analysis set

Overall, TEAEs since prior visit were reported in 25.6%, 14.2%, and 9.3% of patients at 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively (FAS; Table 2). In patients with reported TEAE severity, 12.9%, 7.0%, and 6.4% of TEAEs were severe at 3, 6, and 12 months. During the whole study, four patients died (one due to suicide at 3 months, one due to sudden unexpected death in epilepsy, and for two there was no further information). Of these, three deaths had no date recorded and were disregarded from the analyses, as death may have occurred after the 12 months’ follow-up. Incidences of psychiatric, cognitive, and behavioural TEAEs were low at 3, 6, and 12 months.

3.3 Subgroup Analyses by Seizure Type at Baseline

Subgroup analyses by seizure type at baseline included 861 patients with focal-onset seizures without secondary generalisation, 678 patients with focal-onset seizures with secondary generalisation (seizure subtype was documented for 424 patients, and inferred for the remaining 254 patients), and 162 patients with generalised-onset seizures (more than one seizure type could have been recorded) (FAS; Table S4, see ESM).

At index, the median (Q1, Q3) BRV dose was lower in patients with focal-onset seizures without secondary generalisation (50.0 [50.0, 100.0] mg/day) than in the other seizure subgroups (focal-onset seizures with secondary generalisation: 100.0 [50.0, 100.0] mg/day; generalised-onset seizures: 100.0 [100.0, 150.0] mg/day). At 12 months, the median (Q1, Q3) BRV dose was 200.0 (100.0, 200.0) mg/day in patients with focal-onset seizures without or with secondary generalisation, and 175.0 (100.0, 200.0) mg/day in patients with generalised-onset seizures (Table S2, see ESM). The median (Q1, Q3) duration of exposure to BRV was 349.4 (146.0, 400.0) days in patients with focal-onset seizures without secondary generalisation (n = 857), 337.1 (115.4, 415.5) days in patients with focal-onset seizures with secondary generalisation (n = 670), and 277.0 (123.0, 505.0) days in patients with generalised-onset seizures (n = 160). BRV discontinuations during the whole study follow-up were similar in each subgroup (focal-onset seizures without secondary generalisation: 32.2%; focal-onset seizures with secondary generalisation: 33.7%; generalised-onset seizures: 31.1% [Table S3, see ESM]).

Seizure assessments included all seizures recorded during follow-up. At 12 months, the proportions of patients with ≥ 50% seizure reduction (mFAS), seizure freedom (FAS), and continuous seizure freedom (FAS), were 40.4%, 12.1%, and 7.5%, respectively, in patients with focal-onset seizures without secondary generalisation at baseline; 34.0%, 18.1%, and 16.7% in patients with focal-onset seizures with secondary generalisation at baseline; and 24.0%, 18.8%, and 15.6% in patients with generalised-onset seizures at baseline (Fig. 3a–c). BRV retention at 3, 6, and 12 months was similar in all three subgroups (FAS; Fig. 3d).

Analyses of effectiveness by seizure type at baseline. n represents the number of patients with data for the reported variable at each visit. Patients with missing data were excluded from all seizure analyses. Patients with missing data after BRV discontinuation were considered non-responders and not seizure free. BRV brivaracetam, FAS full analysis set, mFAS modified full analysis set

At 12 months, TEAEs were reported by 10.0%, 9.7%, and 4.0% of patients with focal-onset seizures without secondary generalisation, patients with focal-onset seizures with secondary generalisation, and patients with generalised-onset seizures, respectively (FAS; Table S5, see ESM).

3.4 Subgroup Analyses by Number of Prior ASMs

Subgroup analyses by number of prior ASMs included 1620 patients; 15.4%, 21.9%, 28.8%, and 34.0% had 0–1, 2–3, 4–6, and ≥ 7 prior ASMs, respectively (FAS; Table 1). Patients with ≥ 7 prior ASMs had a longer epilepsy duration (median 22.0 vs 14.0–16.0 years) and a higher seizure frequency at index (median 8.0 vs 2.0–4.0 seizures/28 days) compared with those with fewer prior ASMs (Table S4, see ESM).

At index, median (Q1, Q3) BRV dose was 100.0 (50.0, 150.0) mg/day in patients with 0–1 prior ASMs (n = 246), and 100.0 (50.0, 100.0) mg/day in all other prior ASM subgroups (2–3/4–6/≥ 7 prior ASMs: n = 349/454/542). At 12 months, median (Q1, Q3) BRV dose was 175.0 (100.0, 200.0) mg/day in patients with 0–1 prior ASMs (n = 89), 200.0 (100.0, 200.0) mg/day in patients with 2–3 (n = 150) and 4–6 (n = 220) prior ASMs, and 200.0 (150.0, 200.0) mg/day in patients with ≥ 7 prior ASMs (n = 233). The median (Q1, Q3) duration of exposure to BRV was 350.0 days (126.0, 488.0), 343.9 days (130.0, 403.0), 357.0 days (161.0, 417.6), and 322.0 days (120.0, 401.2), in the 0–1 (n = 246), 2–3 (n = 353), 4–6 (n = 461), and ≥7 (n = 545) prior ASMs subgroups, respectively.

During the whole study follow-up, 27.4%, 31.1%, 30.3%, and 41.4% of patients in the 0–1, 2–3, 4–6, and ≥ 7 prior ASMs subgroups, respectively, discontinued BRV (Table S3, see ESM). Among patients who discontinued BRV, discontinuation due to lack of effectiveness increased as the number of prior ASMs increased, from 27.3% in the 0–1 prior ASM subgroup to 54.0% in the ≥ 7 prior ASMs subgroup. BRV discontinuation due to a tolerability reason decreased as the number of prior ASMs increased, from 43.9% in the 0–1 prior ASM subgroup to 28.1% in the ≥ 7 prior ASMs subgroup.

In general, ≥ 50% seizure reduction (mFAS), seizure freedom (FAS), and continuous seizure freedom (FAS) at 3, 6, and 12 months declined as the number of prior ASMs increased (Fig. 4a–c). BRV retention at 3 months was similar across prior ASM subgroups, whereas retention at 6 and 12 months generally declined as the number of prior ASMs increased (FAS; Fig. 4d). TEAE incidence at 12 months since the prior visit (FAS) was numerically higher in patients with 4–6 and ≥ 7 prior ASMs (11.5% and 10.0%, respectively) versus patients with 0–1 and 2–3 prior ASMs (7.0% and 7.4%, respectively; Table S5, see ESM).

Analyses of effectiveness by number of prior ASMs at index. n represents the number of patients with data for the reported variable at each visit. Patients with missing data were excluded from all seizure analyses. Patients with missing data after BRV discontinuation were considered non-responders and not seizure free. ASM antiseizure medication, BRV brivaracetam, FAS full analysis set, mFAS modified full analysis set

3.5 Monotherapy Versus Polytherapy at Index

Subgroup analyses by BRV treatment type included 1644 patients; 45 (2.7%) were on monotherapy and 1599 (97.3%) were on polytherapy (FAS; Table S4, see ESM). Compared with patients on polytherapy, patients on BRV monotherapy had a shorter epilepsy duration (median 9.0 vs 18.0 years) and a lower number of prior ASMs (median [Q1, Q3] 3.0 [1.0, 4.0] vs 5.0 [2.0, 8.0]). Median (Q1, Q3) BRV dose at index was 100.0 (50.0, 100.0) mg/day in both subgroups (monotherapy/polytherapy: n = 45/1570). Median (Q1, Q3) BRV dose at 12 months was 100.0 (100.0, 200.0) mg/day and 200.0 (100.0, 200.0) mg/day in patients on monotherapy (n = 17) and polytherapy (n = 693), respectively, and median (Q1, Q3) duration of exposure to BRV was 253.0 (91.5, 371.0) days (n = 44) and 347.0 (133.0, 412.1) days (n = 1585). During the whole study follow-up, 24.4% of patients on BRV monotherapy and 33.9% of patients on polytherapy discontinued BRV (Table S3, see ESM). In both subgroups, the most common reason for BRV discontinuation (among patients with a documented reason) was tolerability.

A similar percentage of patients on BRV monotherapy and polytherapy achieved ≥ 50% seizure reduction at 3 months, but a numerically lower percentage of patients on monotherapy achieved ≥ 50% seizure reduction at 6 months and 12 months (mFAS; Fig. 5a). Patients on BRV monotherapy had numerically higher seizure freedom and continuous seizure freedom rates at 3, 6, and 12 months than patients on polytherapy (FAS; Fig. 5b, c). BRV retention at 3, 6, and 12 months was similar in patients on BRV monotherapy and polytherapy (FAS; Fig. 5d).

Analyses of effectiveness by use of BRV as monotherapy or polytherapy at index date. n represents the number of patients with data for the reported variable at each visit. Patients with missing data were excluded from all seizure analyses. Patients with missing data after BRV discontinuation were considered non-responders and not seizure free. BRV brivaracetam, FAS full analysis set, mFAS modified full analysis set

Of the 1174 patients on polytherapy at index who were still on BRV 12 months after initiation and had documented concomitant ASMs, 119 (10.1%) had converted to BRV monotherapy. TEAE incidence at 12 months was numerically lower in patients on BRV monotherapy versus polytherapy (3.8% vs 9.5%) (FAS; Table S5, see ESM).

3.6 Patients Who Switched From LEV to BRV Versus Patients Who Switched From Other ASMs to BRV

Of 1619 patients with data on switching (at index), 709 (43.8%) switched from LEV and 887 (54.8%) switched from other ASMs (not including LEV; FAS). Among patients with data on the reasons for switching from LEV to BRV (n = 583), the most common reasons were lack of effectiveness (232 [39.8%]), tolerability unrelated to behavioural AEs (BAEs) (223 [38.3%]), and BAEs (103 [17.7%]) (reasons were not mutually exclusive).

Median (Q1, Q3) BRV dose at index and at 12 months was higher in patients who switched from LEV (100.0 [50.0, 200.0] mg/day, n = 699; 200.0 [150.0, 200.0] mg/day, n = 321) compared with those who switched from other ASMs (50.0 [50.0, 100.0] mg/day, n = 869; 150.0 [100.0, 200.0] mg/day, n = 368). The median (Q1, Q3) duration of exposure to BRV was 353.1 (167.4, 420.0) days in patients who switched from LEV to BRV (n = 703) and 337.4 (119.0, 401.2) days in patients who switched from other ASMs to BRV (n = 878). During the whole study follow-up, 32.0% of patients who switched from LEV and 35.8% of patients who switched from other ASMs discontinued BRV (Table S3, see ESM).

In both subgroups, ≥ 50% seizure reduction (mFAS), seizure freedom (FAS), continuous seizure freedom (FAS), and BRV retention (FAS) at 3, 6, and 12 months were similar (Fig. 6a–d). The incidence of TEAEs at 12 months was similar in patients who switched from LEV and those who switched from other ASMs to BRV (9.5% vs 9.1%) (FAS; Table S5, see ESM). At 12 months, the incidences of irritability and aggression were 1.3% and 0.8%, respectively, in patients who switched from LEV (n = 525), and 0.5% and 0.3% in patients who switched from other ASMs (n = 662).

Analyses of effectiveness in patients who switched from LEV to BRV and in patients who switched from other ASMs at index. n represents the number of patients with data for the reported variable at each visit. Patients with missing data were excluded from all seizure analyses. Patients with missing data after BRV discontinuation were considered non-responders and not seizure free. ASM antiseizure medication, BRV brivaracetam, FAS full analysis set, LEV levetiracetam, mFAS modified full analysis set

3.7 Patients With Focal-Onset Seizures Who Were on a BRV Dose of ≤ 200 mg/day Used as Add-On at Index

The FAS included 1430 patients of ≥ 16 years of age with focal-onset seizures at baseline and a BRV dose of ≤ 200 mg/day used as add-on at index (Table S6, see ESM). Patient disposition, baseline demographics, and BRV dosing during follow-up were similar to those observed in the overall population (Table 1 and Table S2, see ESM). During the whole study follow-up, 33.6% of patients discontinued BRV (Table S3, see ESM). The most common reasons for BRV discontinuation were lack of effectiveness and/or tolerability. Among patients with a documented reason for BRV discontinuation, 44.8% discontinued due to lack of effectiveness, 33.3% due to tolerability, and 14.7% due to lack of effectiveness and tolerability (reasons were not mutually exclusive). At 3, 6, and 12 months, ≥ 50% seizure reduction was achieved by 31.4%, 36.8%, and 38.1% of patients, respectively (mFAS; Fig. S4a, see ESM), seizure freedom was achieved by 20.8%, 17.1%, and 14.4%, and continuous seizure freedom by 20.8%, 15.2%, and 11.2% (FAS; Fig. S4b–c, see ESM). BRV retention was 89.6%, 79.6%, and 71.2% at 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively (FAS; Fig. S4d, see ESM). TEAEs since prior visit were reported in 26.4%, 15.3%, and 9.9% of patients at 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively (FAS; Table S7, see ESM).

4 Discussion

This international pooled analysis used individual patient records from patients initiating BRV in the real world across a range of geographic locations, clinics, and patient subgroups. Effectiveness of BRV was demonstrated by ≥ 50% seizure reduction, seizure freedom, continuous seizure freedom, and retention at 3, 6, and 12 months. BRV was generally well tolerated, and no new safety concerns were identified. During the whole study follow-up, approximately one third of patients discontinued BRV, mostly due to lack of effectiveness and/or tolerability reasons. Similar effectiveness and tolerability of BRV was observed in comparison with the overall population when the analyses were restricted to patients with focal-onset seizures who had a BRV dose of ≤ 200 mg/day used as add-on at index. This subgroup represented patients who initiated BRV per either the European Summary of Product Characteristics [17], the Australian Product Information [18], or the US Prescribing Information [19].

Key strengths of EXPERIENCE include the large volume of pooled real-world evidence from individual patient records, which permitted subgroup analyses. The EXPERIENCE results are consistent with published data from three phase III, randomised, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose trials that assessed the efficacy and tolerability of BRV for adjunctive treatment of focal-onset seizures in patients ≥ 16 years of age [2,3,4]. The eligibility criteria for the retrospective real-world evidence studies were broader than those of the randomised controlled trials, leading to inclusion of a more diverse patient population. Despite this, the study population was composed of highly drug-resistant patients as evidenced by their baseline characteristics (median of 5.0 prior ASMs and 2.0 concomitant ASMs at index, median seizure frequency of 4.0/28 days at index). Patient enrolment began as soon as BRV became available in each country, which likely contributed to the drug-resistant population. Patients who have experienced a suboptimal response to existing therapies may expect improved effectiveness and tolerability with new medications [20]. Therefore, some patients switching to BRV in the immediate post-launch phase likely did so due to failure of established ASMs. Effectiveness of BRV was demonstrated in patients with highly drug-resistant epilepsy despite the stringent approach used for seizure analyses: patients with missing data due to BRV discontinuation were considered to be non-responders for ≥ 50% seizure reduction and not seizure free.

Subgroup analyses by seizure type were based on seizure type recorded at baseline (focal-onset seizures with secondary generalisation, focal-onset seizures without secondary generalisation, or generalised-onset seizures). More than one seizure type could be recorded. Unfortunately, it was not possible to extract data on specific seizure types during follow-up. As such, the effectiveness outcomes of seizure reduction, seizure freedom, and continuous seizure freedom were based on assessment of all recorded seizure types. This differs from the approach used in published post-hoc analyses by Moseley et al. [21, 22], which sought to assess effectiveness outcomes for a specific seizure subtype. The analyses performed by Moseley et al. included patients with focal-onset seizures with secondary generalisation at baseline, and extracted seizure assessment data specifically for this seizure type during follow-up. Despite being unable to report data for specific seizure types, EXPERIENCE suggests that BRV may be an effective treatment for patients with generalised-onset seizures as well as for patients with focal-onset seizures. These results are supported by data from a multicentre retrospective study that showed off-label BRV was effective in 69 patients with genetic generalised epilepsies, with 50% responder rates similar to those observed in phase III trials of BRV in patients with focal seizures [23].

An increasing number of previous ASMs is associated with a poorer treatment response to a newly administered ASM [24]. In EXPERIENCE, subgroup analyses by number of prior ASMs showed that patients with fewer prior ASMs generally achieved numerically higher ≥ 50% seizure reduction, seizure freedom, continuous seizure freedom, and BRV retention at 12 months. This is consistent with data from the observational, retrospective BRIVAracetam add‑on First Italian netwoRk STudy (BRIVAFIRST) showing that a lower number of prior ASMs was a predictor of higher rates of seizure freedom, sustained seizure reduction, and sustained seizure freedom with adjunctive BRV in patients with focal seizures [25, 26], and with data from a phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study showing that response to adjunctive BRV treatment was higher in patients with fewer prior ASMs [4]. The EXPERIENCE analysis differed from these studies in that patients could have either focal or generalised-onset seizures and were receiving BRV as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy.

Post-hoc analyses [27] of long-term data from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial and corresponding open-label extension of adjunctive BRV in adults with focal-onset seizures only showed that although BRV retention and efficacy were higher in patients exposed to fewer lifetime (prior and concomitant) ASMs, patients with ≥ 7 lifetime ASMs could still benefit from BRV treatment. Similar results were observed in EXPERIENCE. Clinically meaningful seizure reductions were seen in all prior ASM subgroups, including those with ≥ 7 ASMs, and high retention suggested that patients were generally satisfied with their treatment. BRV discontinuation due to tolerability reasons alone (i.e., not in combination with lack of effectiveness) decreased as the number of prior ASMs increased, and BRV discontinuation due to lack of effectiveness alone (i.e., not in combination with a tolerability reason) increased as the number of prior ASMs increased. These data suggest that patients exposed to a higher number of prior ASMs may be more willing to accept tolerability issues in return for effectiveness gains. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the effect of the number of prior ASMs on BRV discontinuation.

Given the small number of patients on monotherapy in EXPERIENCE (n = 45), data for subgroup analyses by BRV treatment type should be interpreted with caution. However, these analyses add to the limited published real-world evidence data on patients on BRV monotherapy. Subgroup analyses by BRV treatment type showed that patients on polytherapy versus monotherapy had a numerically higher ≥ 50% seizure reduction at 12 months. Although patients on monotherapy achieved higher rates of seizure freedom and continuous seizure freedom at 12 months, clinically meaningful continuous seizure freedom was still seen with polytherapy.

A post-hoc analysis of data from a pivotal phase III randomised, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose trial [4] showed adjunctive BRV was effective in patients with previous LEV exposure and in LEV-naïve patients. The efficacy of BRV appeared to be lower in patients who had previously received LEV, which was expected as both ASMs exert their antiseizure activity through binding to the synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A receptor site. In a subsequent post-hoc analysis of pooled data from three phase III studies, adjunctive BRV, compared with placebo, was shown to be more efficacious in ASM-naïve patients than in patients with previous exposure to LEV, carbamazepine (CBZ), topiramate (TPM), or lamotrigine (LTG), irrespective of the mechanism of action of the previous ASM. The authors concluded that previous treatment failure with LEV does not preclude the use of BRV [28]. Furthermore, a post-hoc analysis of data from a phase III trial and corresponding open-label extension study showed long-term BRV retention and reasons for BRV discontinuation were similar amongst subgroups of patients previously treated with LEV, CBZ, LTG, or TPM [29]. In line with these results, the EXPERIENCE study showed similar effectiveness (≥ 50% seizure reduction, seizure freedom, continuous seizure freedom, and BRV retention) and tolerability of BRV in patients who switched from LEV and patients who switched from other ASMs. As such, BRV can be considered as a treatment option for patients with epilepsy who have failed other ASMs, including LEV.

LEV treatment has been associated with non-psychotic BAEs [30], and switching from LEV to BRV may improve BAEs [31]. In EXPERIENCE, among the patients who switched from LEV to BRV, 17.7% reported tolerability (BAE) as a reason for switching. Analyses of TEAEs showed low incidences of irritability and aggression in patients switching from LEV to BRV, as well as in patients switching from other ASMs.

A limitation of EXPERIENCE was that, due to the inclusion of pooled data from existing retrospective studies, any shortcomings from the original studies could not be mitigated. The original studies were heterogeneous in study populations, objectives, and information reported. There may have been misclassification bias due to coding errors that could not be eliminated by data logic checks (due to patient anonymisation as per GDPR), and there was a high level of missing data. Data were not available for all patients at all timepoints, across all endpoints and assessments. The restriction to patients with ≥ 6 months of follow-up may have introduced a selection bias, as patients with short follow-up are often of worse prognosis. This requirement may have enriched the EXPERIENCE population with treatment responders; therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution. The requirement for ≥ 6 months of follow-up may also have impacted incidence of TEAEs, as drug-related TEAEs and discontinuations due to TEAEs are most common during the first few weeks of treatment [32]. In EXPERIENCE, 20% of patients discontinued BRV during the first 6 months of treatment. It is possible that a similar percentage of patients were excluded from the analyses for each cohort due to lack of follow-up data. Analyses of BRV discontinuation due to tolerability included patients on polytherapy, some of whom may have discontinued due to intolerability for a concomitant ASM. As data for specific seizure types were not recorded for all patients, the analyses by seizure type at baseline included some patients for whom the subtype of focal-onset seizures with secondary generalisation was inferred rather than documented. It is possible that some seizures that were recorded as being primary generalised seizures may, in some cases, be secondarily generalised seizures. Finally, as there was no control group, comparison of BRV with another ASM was not possible. Despite these limitations, EXPERIENCE provides 12-month clinical data for BRV with a sufficient sample size to assess effectiveness and tolerability among key subpopulations of interest. As such, EXPERIENCE provides real-world data on the effectiveness and tolerability of BRV in patients with different seizure types, by number of prior ASMs, in patients on monotherapy versus polytherapy, and in patients switching to BRV from LEV versus those switching from ASMs with different mechanisms of action.

Since the identification of studies for inclusion in the EXPERIENCE analysis, 12-month outcomes from two other real-world studies of adjunctive BRV in patients ≥ 16 years of age with focal-onset seizures have been published: BRIVAFIRST, a retrospective, multicentre study in Italy [26]; and EP0077 (or Brivaracetam And Seizure reduction in Epilepsy [BASE]), a prospective, observational study in Europe [33]. In EXPERIENCE, the percentage of patients that achieved ≥ 50% seizure reduction at 12 months (36.9%) was similar to that in BRIVAFIRST (37.2%) [26], but lower than that in EP0077 (60.4%) (unpublished data). Additionally, seizure freedom at 12 months (continuous seizure freedom: 11.7%) was similar to that reported in BRIVAFIRST (16.4%) [26] and EP0077 (13.8%) (unpublished data), although BRIVAFIRST used a different definition for this outcome (no seizures within the previous 6 months). The 12-month retention on BRV in EXPERIENCE (71.1%) was similar to that in BRIVAFIRST (74.2%), but higher than that in EP0077 (57.7%) [26, 33]. The TEAE profile in EXPERIENCE was consistent with that in BRIVAFIRST and EP0077 [26, 33]. Any differences reported between EXPERIENCE, BRIVAFIRST, and EPP0077 may reflect differences in study design and baseline patient demographics. EXPERIENCE included patients with generalised-onset seizures in addition to focal-onset seizures; data from international retrospective studies from outside of Europe; and patients on BRV as monotherapy, as well as patients on BRV as adjunctive therapy.

5 Conclusions

This pooled analysis of a large international population using data from a variety of real-world settings suggests that BRV is effective and well tolerated in highly drug-resistant patients with epilepsy. Analyses by prior ASMs suggest greater effectiveness and tolerability of BRV in patients who have been exposed to fewer prior ASMs. The results provide additional evidence that BRV as prescribed in the real world is effective and well tolerated among patients on monotherapy, for different types of seizures, and for patients who have switched to BRV from other ASMs, including LEV.

References

Wood MD, Gillard M. Evidence for a differential interaction of brivaracetam and levetiracetam with the synaptic vesicle 2A protein. Epilepsia. 2017;58(2):255–62.

Biton V, Berkovic SF, Abou-Khalil B, Sperling MR, Johnson ME, Lu S. Brivaracetam as adjunctive treatment for uncontrolled partial epilepsy in adults: a phase III randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Epilepsia. 2014;55(1):57–66.

Ryvlin P, Werhahn KJ, Blaszczyk B, Johnson ME, Lu S. Adjunctive brivaracetam in adults with uncontrolled focal epilepsy: results from a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Epilepsia. 2014;55(1):47–56.

Klein P, Schiemann J, Sperling MR, Whitesides J, Liang W, Stalvey T, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, parallel-group study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of adjunctive brivaracetam in adult patients with uncontrolled partial-onset seizures. Epilepsia. 2015;56(12):1890–8.

Fisher RS, Cross JH, French JA, Higurashi N, Hirsch E, Jansen FE, et al. Operational classification of seizure types by the International League Against Epilepsy: position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia. 2017;58(4):522–30.

Villanueva V, López-González FJ, Mauri JA, Rodriguez-Uranga J, Olivé-Gadea M, Montoya J, et al. BRIVA-LIFE—a multicenter retrospective study of the long-term use of brivaracetam in clinical practice. Acta Neurol Scand. 2019;139(4):360–8.

Fonseca E, Guzmán L, Quintana M, Abraira L, Santamarina E, Salas-Puig X, et al. Efficacy, retention, and safety of brivaracetam in adult patients with genetic generalized epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;102:106657.

Bhathal Guede H, Salas-Puig X. BRIVARCAT: Estudio observacional de BRIVaracetam en ARagón y CATaluña, como terapia añadida en epilepsia farmacorresistente. Presented at XXII Reunió Anual de la Societat Catalana de Neurologia, 22–23 May 2018, Barcelona, Spain.

Steinig I, von Podewils F, Möddel G, Bauer S, Klein KM, Paule E, et al. Postmarketing experience with brivaracetam in the treatment of epilepsies: a multicenter cohort study from Germany. Epilepsia. 2017;58(7):1208–16.

Strzelczyk A, Zaveta C, von Podewils F, Möddel G, Langenbruch L, Kovac S, et al. Long-term efficacy, tolerability, and retention of brivaracetam in epilepsy treatment: a longitudinal multicenter study with up to 5 years of follow-up. Epilepsia. 2021;62(12):2994–3004.

Steinhoff BJ, Bacher M, Bucurenciu I, Hillenbrand B, Intravooth T, Kornmeier R, et al. Real-life experience with brivaracetam in 101 patients with difficult-to-treat epilepsy—a monocenter survey. Seizure. 2017;48:11–4.

Zahnert F, Krause K, Immisch I, Habermehl L, Gorny I, Chmielewska I, et al. Brivaracetam in the treatment of patients with epilepsy—first clinical experiences. Front Neurol. 2018;9:38.

Halliday AJ, Vogrin S, Whitham E, Seneviratne U, Gillinder S, Jones D, et al. Real-world brivaracetam efficacy in adult epilepsy: an Australian multi-centre retrospective observational cohort study. Presented at ANZAN 2022, 10–13 May 2022, Melbourne, Australia.

Adewusi J, Burness C, Ellawela S, Emsley H, Hughes R, Lawthom C, et al. Brivaracetam efficacy and tolerability in clinical practice: a UK-based retrospective multicenter service evaluation. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;106:106967.

Ferragut Ferretjans F, Soto Insuga V, Bernardino Cuesta B, Cantarín Extremera V, Duat Rodriguez A, Legido MJ, et al. Efficacy of brivaracetam in children with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2021;177:106757.

Daniels T, Soto Insuga V, D'Souza W, Faught E, Klein P, Reuber M, et al. 12-month effectiveness and tolerability of brivaracetam in pediatric patients in the real-world: subgroup data from the EXPERIENCE analysis. Presented at American Epilepsy Society—76th, 2–6 December 2022, Nashville, TN. Abstract 1.301.

UCB Pharma S.A. Briviact® (brivaracetam) EU Summary of Product Characteristics. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/briviact-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 20 Jan 2023.

UCB Pharma. Product Information Briviact. 2017. https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/auspar-brivaracetam-170307-pi-01.pdf. Accessed 20 Jan 2023.

UCB Inc. Briviact® (brivaracetam) prescribing information. 2023. https://www.briviact.com/briviact-PI.pdf. Accessed 31 Aug 2023.

Schneeweiss S, Gagne JJ, Glynn RJ, Ruhl M, Rassen JA. Assessing the comparative effectiveness of newly marketed medications: methodological challenges and implications for drug development. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;90(6):777–90.

Moseley BD, Sperling MR, Asadi-Pooya AA, Diaz A, Elmoufti S, Schiemann J, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of adjunctive brivaracetam for secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures: pooled results from three phase III studies. Epilepsy Res. 2016;127:179–85.

Moseley BD, Dimova S, Elmoufti S, Laloyaux C, Asadi-Pooya AA. Long-term efficacy and tolerability of adjunctive brivaracetam in adults with focal to bilateral tonic-clonic (secondary generalized) seizures: post hoc pooled analysis. Epilepsy Res. 2021;176:106694.

Strzelczyk A, Kay L, Bauer S, Immisch I, Klein KM, Knake S, et al. Use of brivaracetam in genetic generalized epilepsies and for acute, intravenous treatment of absence status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2018;59(8):1549–56.

Schiller Y, Najjar Y. Quantifying the response to antiepileptic drugs: effect of past treatment history. Neurology. 2008;70(1):54–65.

Lattanzi S, Ascoli M, Canafoglia L, Paola Canevini M, Casciato S, Cerulli Irelli E, et al. Sustained seizure freedom with adjunctive brivaracetam in patients with focal onset seizures. Epilepsia. 2022;63(5):e42–50.

Lattanzi S, Canafoglia L, Canevini MP, Casciato S, Chiesa V, Dainese F, et al. Adjunctive brivaracetam in focal epilepsy: real-world evidence from the BRIVAracetam add-on First Italian netwoRk STudy (BRIVAFIRST). CNS Drugs. 2021;35(12):1289–301.

Brandt C, Dimova S, Elmoufti S, Laloyaux C, Nondonfaz X, Klein P. Retention, efficacy, tolerability, and quality of life during long-term adjunctive brivaracetam treatment by number of lifetime antiseizure medications: a post hoc analysis of phase 3 trials in adults with focal seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2023;138:108967.

Asadi-Pooya AA, Sperling MR, Chung S, Klein P, Diaz A, Elmoufti S, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of adjunctive brivaracetam in patients with prior antiepileptic drug exposure: a post-hoc study. Epilepsy Res. 2017;131:70–5.

Chung S, Martin M, Dimova S, Elmoufti S, Laloyaux C. Long-term retention on adjunctive brivaracetam in adults with focal seizures previously exposed to carbamazepine, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, or topiramate: a post hoc analysis. Neurology. 2019;92:P5.5-012.

Yates SL, Fakhoury T, Liang W, Eckhardt K, Borghs S, D’Souza J. An open-label, prospective, exploratory study of patients with epilepsy switching from levetiracetam to brivaracetam. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;52(Pt A):165–8.

Steinhoff BJ, Klein P, Klitgaard H, Laloyaux C, Moseley BD, Ricchetti-Masterson K, et al. Behavioral adverse events with brivaracetam, levetiracetam, perampanel, and topiramate: a systematic review. Epilepsy Behav. 2021;118:107939.

Meador KJ, Laloyaux C, Elmoufti S, Gasalla T, Fishman J, Martin MS, et al. Time course of drug-related treatment-emergent adverse side effects of brivaracetam. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;111:107212.

Steinhoff BJ, Christensen J, Doherty CP, Majoie M, Schulz A-L, Brock F, et al. Cognitive performance and retention after 12-month adjunctive brivaracetam in difficult-to-treat patients with epilepsy in a real-life setting. In: 34th International Epilepsy Congress Virtual 28 August–1 September 2021; abstract/poster 96. Epilepsia. 2021;62(S3):3–364.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients and their caregivers in addition to the investigators and their teams who contributed to the retrospective studies included in this pooled analysis. The authors would like to acknowledge Kristen Ricchetti-Masterson, MSPH, PhD (Sarepta Therapeutics, Cambridge, MA, USA) and Sophia Zhou, MS (formerly UCB Pharma, Morrisville, NC, USA) for their contributions to the study. Publication management was provided by Tom Grant, PhD (UCB Pharma, Slough, UK). Writing assistance was provided by Emma Budd, PhD (Evidence Scientific Solutions, Horsham, UK) and was funded by UCB Pharma.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by UCB Pharma. The sponsor was involved in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, and in the decision to publish the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

VV has served as a consultant or on an advisory board, for Arvelle Therapeutics, Bial, Eisai, Esteve, GW Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, and UCB Pharma; has received research grants from Bial, Eisai, and UCB Pharma; and has received speaker’s honoraria from Bial, Eisai, Esteve, GW Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, and UCB Pharma. WDS has a salary that is part-funded by The University of Melbourne; he has received travel, investigator-initiated, scientific advisory board, and speaker honoraria from UCB Pharma Australia & Global; investigator-initiated, scientific advisory board, travel, and speaker honoraria from Eisai Australia & Global; advisory board honoraria from LivaNova and Tilray; educational grants from Novartis, Pfizer, and Sanofi-Synthélabo; educational, travel, and fellowship grants from GSK Neurology Australia; and honoraria from ScieGen Pharmaceuticals; he has an equity interest in the device company Epiminder. EF has received research grants from Janssen and UCB Pharma, and has served as a consultant for Aucta, Biogen, Eisai, LivaNova, Neurelis, SK Life Science, and Trevena. PK has served as a consultant for Abbott, Arvelle Therapeutics, Neurelis, and SK Life Science; as a consultant, advisory board member, and speaker for Aquestive, Eisai, Sunovion, and UCB Pharma; is a member of the medical advisory board of Stratus and the scientific advisory board of OB Pharma; is the CEO of PrevEp; and has received research support from CURE and Department of Defense/Lundbeck. MR receives payment from Elsevier as editor-in-chief of Seizure; and has received research grants and speaker’s fees from Eisai, LivaNova, and UCB Pharma. FR reports personal fees from Angelini Pharma, Arvelle Therapeutics, Eisai GmbH, GW Pharmaceuticals; personal fees and other from Novartis; personal fees and grants from UCB Pharma; and grants from the Detlev-Wrobel-Fonds for Epilepsy Research Frankfurt, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the European Union, and the State of Hessen outside of the submitted work. JSP has received grants from Bial and UCB Pharma; and reports personal fees from Bial, Eisai, Esteve, Sanofi, and UCB Pharma outside of the submitted work. VSI has received speaker honoraria from Bial, Eisai, and UCB Pharma. AS reports personal fees and grants from Angelini Pharma, Desitin Arzneimittel, Eisai, GW/Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Marinus Pharma, Precisis, Takeda, UCB Pharma/Zogenix, and UNEEG Medical, outside of the submitted work. JPS has received research funding from Biogen, Department of Defense, Eisai, GW Pharmaceuticals companies, National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation, NeuroPace, Serina Therapeutics, Shor Foundation for Epilepsy Research, State of Alabama General Funds, and UCB Pharma; has served as a consultant or advisory board member for Elite Medical Experts, GW Pharmaceuticals companies, LivaNova, Lundbeck, Medical Association of the State of Alabama, NeuroPace, Serina Therapeutics, SK Life Science, and UCB Pharma; has served as an investigator on GW Research Ltd trials; and is an editorial board member for Epilepsy & Behavior, Epilepsy & Behavior Reports (editor-in-chief), Folia Medica Copernicana, Journal of Epileptology (associate editor), and Journal of Medical Science. HB, CC, TD, FF, CL, and VS are employees of UCB Pharma. DF is an independent contractor working for UCB Pharma. BJS has received speaker honoraria from Al-Jazeera, Desitin, Eisai, GW Pharmaceuticals, Hikma, Novartis, Sandoz, and UCB Pharma; and has served as a consultant for Arvelle Therapeutics, B. Braun, Bial, Desitin, Eisai, GW Pharmaceuticals, and UCB Pharma. We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Availability of data and material

Data from non-interventional studies are outside of UCB Pharma’s data sharing policy and are unavailable for sharing.

Ethics approval

No ethics committee approval was required for the EXPERIENCE database given that the database consisted of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) compliant anonymised data. The Australian (AUS) and United States of America (USA) cohorts required ethics approval to release their data for inclusion in the EXPERIENCE database. Each non-interventional study that was included in EXPERIENCE received appropriate ethics and/or scientific review board approval as part of the initial study proposal at each institution.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to study conception/design, or acquisition/analysis/interpretation of data; and drafting of the manuscript, or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and provided final approval of the manuscript.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Villanueva, V., Laloyaux, C., D’Souza, W. et al. Effectiveness and Tolerability of 12-Month Brivaracetam in the Real World: EXPERIENCE, an International Pooled Analysis of Individual Patient Records. CNS Drugs 37, 819–835 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-023-01033-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-023-01033-4