Abstract

Background

Since the approval and availability of the first biosimilar in 2015 in the United States (US), evidence regarding the post-marketing safety of cancer supportive care biosimilars remains limited.

Objective

The aim was to explore the adverse event (AE) reporting patterns and detect disproportionate reporting signals for cancer supportive care biosimilars in the US compared to their originator biologics.

Methods

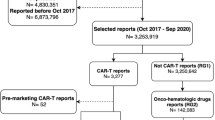

The US Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System database (January 1, 2004–March 31, 2020) was used to identify AE reports for filgrastim, pegfilgrastim, and epoetin alpha by type of product (originator biologics vs. biosimilars) and report characteristics. Plots of AE reports against years were used to reveal the reporting patterns. Disproportionality analyses using reporting odds ratios (RORs) were conducted to detect differences in serious and specific AEs between studied drugs and all other drugs. Breslow–Day tests were used to determine homogeneity between the originator biologic–biosimilar pair RORs for the same AE.

Results

Total numbers of AEs for all studied biosimilars increased after marketing. More AE reports were from female patients for all of the studied drugs. More AEs for originator biologics and filgrastim biosimilar were reported by health professionals, while the highest proportion of reports came from consumers for pegfilgrastim and epoetin alpha biosimilars (29% and 44.1%, respectively). Signals of disproportionate reporting in serious AEs were detected for a pegfilgrastim biosimilar (Fulphila®) compared to its originator biologic.

Conclusion

Our findings support the similarity in the signals of disproportionate reporting between cancer supportive care originator biologics and biosimilars, except for Fulphila®.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Klastersky J, de Naurois J, Rolston K, Rapoport B, Maschmeyer G, Aapro M, et al. Management of febrile neutropaenia: ESMO clinical practice guidelines & #x2020. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:v111–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdw325.

Tai E Jr., Guy GP, Dunbar A, Richardson LC. Cost of cancer-related neutropenia or fever hospitalizations, United States, 2012. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(6):e552–61. https://doi.org/10.1200/jop.2016.019588.

Ludwig H, Van Belle S, Barrett-Lee P, Birgegård G, Bokemeyer C, Gascón P, et al. The European Cancer Anaemia Survey (ECAS): a large, multinational, prospective survey defining the prevalence, incidence, and treatment of anaemia in cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40(15):2293–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2004.06.019.

Xu H, Xu L, Page JH, Cannavale K, Sattayapiwat O, Rodriguez R, et al. Incidence of anemia in patients diagnosed with solid tumors receiving chemotherapy, 2010–2013. Clin Epidemiol. 2016;8:61–71. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S89480.

Family L. Symptom burdens related to chemotherapy-induced anemia in stage IV cancer. J Community Support Oncol. 2018;16(6):e260–71. https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0432.

Österborg A, Brandberg Y. Relationship between changes in hemoglobin level and quality of life during chemotherapy in anemic cancer patients receiving epoetin alfa therapy. Cancer. 2003;97(12):3125–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.11430.

Patel KB, Arantes LH Jr, Tang WY, Fung S. The role of biosimilars in value-based oncology care. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:4591–602. https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S164201.

McBride A, Campbell K, Bikkina M, MacDonald K, Abraham I, Balu S. Cost-efficiency analyses for the US of biosimilar filgrastim-sndz, reference filgrastim, pegfilgrastim, and pegfilgrastim with on-body injector in the prophylaxis of chemotherapy-induced (febrile) neutropenia. J Med Econ. 2017;20(10):1083–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2017.1358173.

Biosimilars. US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/therapeutic-biologics-applications-bla/biosimilars. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

Biosimilar and Interchangeable Products. US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/biosimilars/biosimilar-and-interchangeable-products. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

Prescribing Biosimilar and Interchangeable Products. US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/biosimilars/prescribing-biosimilar-and-interchangeable-products. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

Biosimilar and Interchangeable Biologics: More Treatment Choices. US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/biosimilar-and-interchangeable-biologics-more-treatment-choices. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

IMS Biosimilar report—The Impact of Biosimilar Competition in Europe. European Commission. 2017. https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/23102. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

Abraham I, Han L, Sun D, MacDonald K, Aapro M. Cost savings from anemia management with biosimilar epoetin alfa and increased access to targeted antineoplastic treatment: a simulation for the EU G5 countries. Future Oncol. 2014;10(9):1599–609. https://doi.org/10.2217/fon.14.43.

Raedler LA. Zarxio (filgrastim-sndz): first biosimilar approved in the United States. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2016;9(Spec Feature):150–4.

Yang J, Yu S, Yang Z, Yan Y, Chen Y, Zeng H, et al. Efficacy and safety of supportive care biosimilars among cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biodrugs. 2019;33(4):373–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-019-00356-3.

Questions and Answers on FDA's Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). US Food and Drug Administration. 2018. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/surveillance/questions-and-answers-fdas-adverse-event-reporting-system-faers. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

Sakaeda T, Tamon A, Kadoyama K, Okuno Y. Data mining of the public version of the FDA adverse event reporting system. Int J Med Sci. 2013;10(7):796–803. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijms.6048.

Purple Book: Database of Licensed Biological Products. US Food and Drug Administration. https://purplebooksearch.fda.gov/. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

National Drug Code Directory. US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/national-drug-code-directory. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

Nonproprietary Naming of Biological Products: Guidance for Industry. US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/nonproprietary-naming-biological-products-guidance-industry. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

Rahman MM, Alatawi Y, Cheng N, Qian J, Peissig PL, Berg RL, et al. Methodological considerations for comparison of brand versus generic versus authorized generic adverse event reports in the US Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). Clin Drug Investig. 2017;37(12):1143–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40261-017-0574-4.

FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. openFDA. 2020. https://open.fda.gov/data/faers/. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

CFR—code of federal regulations title 21 Sec 314.80. Postmarketing Reporting of Adverse Drug Experiences. US Food and Drug Administration. 2015. www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/cfrsearch.cfm. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

ZARXIO™ (filgrastim-sndz). US Food and Drug Administration. 2015. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/125553lbl.pdf. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

NEUPOGEN® (filgrastim) US Food and Drug Administration. 2015. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/103353s5183lbl.pdf. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

NEULASTA® (pegfilgrastim). US Food and Drug Administration. 2015. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/125031s180lbl.pdf. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

Epogen® (epoetin alfa). US Food and Drug Administration. 2017. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/103234s5363s5366lbl.pdf. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

NIVESTYM™ (filgrastim-aafi) US Food and Drug Administration. 2018. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/761080s000lbl.pdf. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

FULPHILA (pegfilgrastim-jmdb). US Food and Drug Administration. 2018. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/761075s000lbl.pdf. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

UDENYCATM (pegfilgrastim-cbqv). US Food and Drug Administration. 2018. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/761039s000lbl.pdf. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

RETACRIT™(epoetin alfa-epbx). US Food and Drug Administration. 2018. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/125545s000lbl.pdf. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

Dale DC, Crawford J, Klippel Z, Reiner M, Osslund T, Fan E, et al. A systematic literature review of the efficacy, effectiveness, and safety of filgrastim. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(1):7–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3854-x.

Standardised MedDRA Queries. MedDRA-Medical dictionary for regulatory activities. https://www.meddra.org/standardised-meddra-queries. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

Szarfman A, Machado SG, O’Neill RTJDS. Use of screening algorithms and computer systems to efficiently signal higher-than-expected combinations of drugs and events in the US FDA’s spontaneous reports database. Drug Saf. 2002;25(6):381–92. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200225060-00001.

Rothman KJ, Lanes S, Sacks ST. The reporting odds ratio and its advantages over the proportional reporting ratio. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2004;13(8):519–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.1001.

Egberts AC, Meyboom RH, van Puijenbroek EP. Use of measures of disproportionality in pharmacovigilance: three Dutch examples. Drug Saf. 2002;25(6):453–8. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200225060-00010.

Shalviri G, Mohammad K, Majdzadeh R, Gholami K. Applying quantitative methods for detecting new drug safety signals in pharmacovigilance national database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(10):1136–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.1459.

Kozlowski S, Birger N, Brereton S, McKean SJ, Wernecke M, Christl L, et al. Uptake of the biologic filgrastim and its biosimilar product among the medicare population. JAMA. 2018;320(9):929–31. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.9014.

Mehr S. An interesting comparison: the latest data on US and EU biosimilar uptake. Biosimilars review and report. 2020. https://biosimilarsrr.com/2020/04/23/an-interesting-comparison-the-latest-data-on-us-and-eu-biosimilar-uptake/. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

Bangia I. Biosimilar uptake varies by class of agent. AJMC—The Center for Biosimilars. 2020. https://www.centerforbiosimilars.com/news/biosimilar-uptake-varies-by-class-of-agent. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

Cohen J. In U.S. Biosimilars run into more roadblocks. Forbes. 2019. https://www.forbes.com/sites/joshuacohen/2019/09/12/in-u-s-biosimilars-run-into-more-roadblocks/#de360f319e9a. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

Barnes G, Pathak A, Schwartzberg L. G-CSF utilization rate and prescribing patterns in United States: associations between physician and patient factors and GCSF use. Cancer Med. 2014;3(6):1477–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.344.

Douglas AG, Schwab P, Lane D, Kennedy K, Slabaugh SL, Bowe A. A comparison of brand and biosimilar granulocyte-colony stimulating factors for prophylaxis of chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(12):1221–6. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.12.1221.

Seetasith A, Holdford D, Shah A, Patterson J. On-label and off-label prescribing patterns of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents in inpatient hospital settings in the US during the period of major regulatory changes. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2017;13(4):778–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.07.005.

Weycker D, Doroff R, Hanau A, Bowers C, Belani R, Chandler D, et al. Use and effectiveness of pegfilgrastim prophylaxis in US clinical practice:a retrospective observational study. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):792. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-6010-9.

Culakova E, Thota R, Poniewierski MS, Kuderer NM, Wogu AF, Dale DC, et al. Patterns of chemotherapy-associated toxicity and supportive care in US oncology practice: a nationwide prospective cohort study. Cancer Med. 2014;3(2):434–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.200.

Chang J. Chemotherapy dose reduction and delay in clinical practice evaluating the risk to patient outcome in adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36(Suppl 1):S11–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00259-2.

Toki T, Ono S. Assessment of factors associated with completeness of spontaneous adverse event reporting in the United States: a comparison between consumer reports and healthcare professional reports. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2020;45(3):462–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.13086.

Chen X, Agiro A, Barron J, Debono D, Fisch M. Early adoption of biosimilar growth factors in supportive cancer care. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(12):1779–81. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.5090.

Hoffman KB, Dimbil M, Erdman CB, Tatonetti NP, Overstreet BM. The Weber Effect and the United States Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS): analysis of sixty-two drugs approved from 2006 to 2010. Drug Saf. 2014;37(4):283–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-014-0150-2.

Kobayashi T, Kamada I, Komura J, Toyoshima S, Ishii-Watabe A. Comparative study of the number of report and time-to-onset of the reported adverse event between the biosimilars and the originator of filgrastim. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26(8):917–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.4218.

Rastogi S, Shukla S, Sharma AK, Sarwat M, Srivastava P, Katiyar T, et al. Towards a comprehensive safety understanding of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor biosimilars in treating chemotherapy associated febrile neutropenia: trends from decades of data. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2020;395:114976. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2020.114976.

Chew C, Ng HY. Efficacy and safety of nivestim versus neupogen for mobilization of peripheral blood stem cells for autologous stem cell transplantation. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):19938. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-56477-w.

Desai K, Misra P, Kher S, Shah N. Clinical confirmation to demonstrate similarity for a biosimilar pegfilgrastim: a 3-way randomized equivalence study for a proposed biosimilar pegfilgrastim versus US-licensed and EU-approved reference products in breast cancer patients receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2018;7(1):22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40164-018-0114-9.

Trotta F, Belleudi V, Fusco D, Amato L, Mecozzi A, Mayer F, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (biosimilars vs originators) in clinical practice: a population-based cohort study in Italy. BMJ Open. 2017;7(3):e011637. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011637.

Stoppa G, D’Amore C, Conforti A, Traversa G, Venegoni M, Taglialatela M, et al. Comparative safety of originator and biosimilar epoetin alfa drugs: an observational prospective multicenter study. Biodrugs. 2018;32(4):367–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-018-0293-2.

Ghosh P, Dewanji A. Effect of reporting bias in the analysis of spontaneous reporting data. Pharm Stat. 2015;14(1):20–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/pst.1657.

Bate A, Lindquist M, Orre R, Edwards I, Meyboom R. Data-mining analyses of pharmacovigilance signals in relation to relevant comparison drugs. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;58(7):483–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-002-0484-z.

Colbert RA, Cronstein BN. Biosimilars: the debate continues. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(10):2848–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.30505.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank and acknowledge Drs. Surachat Ngorsuraches and Kimberly Garza, associate professors at Auburn University Harrison School of Pharmacy, for their feedback on research proposal development. We also thank Mr. Whitt Krehling, Auburn University, for his assistance in editing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No financial assistance was used to conduct the study described in the article and/or used to assist with the preparation of the article.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to report for all authors.

Data Availability

The US FDA FAERS data supporting the results reported in the article can be accessed and downloaded from https://fis.fda.gov/extensions/FPD-QDE-FAERS/FPD-QDE-FAERS.html.

Ethics Approval

The study was granted exemption by the Auburn University Institutional Review Board, and the study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

KAT, CBT, and JQ had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: All authors. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: KAT, CBT, and JQ. Drafting of the paper: All authors. Critical revision of the paper for important intellectual content: All authors. Statistical analysis: KAT and CBT. Study supervision: JQ.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tanni, K.A., Truong, C.B., Almahasis, S. et al. Safety of Marketed Cancer Supportive Care Biosimilars in the US: A Disproportionality Analysis Using the Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) Database. BioDrugs 35, 239–254 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-020-00466-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-020-00466-3