Abstract

Monkeypox (MPVX) infection has been associated with multiorgan presentations. Thus, monkeypox infection’s early and late complications are of particular concern, prompting health systems to decipher threatening sequels and their possible countermeasures. The current article will review the clinical signs and symptoms of the present and former outbreaks, differential diagnoses, workup and treatment of the ocular manifestations of MPXV infection in detail. One of the uncommon yet considerable MPXV complications is ocular involvement. These injuries are classified as (1) more frequent and benign lesions and (2) less common and vision-threatening sequels. Conjunctivitis, blepharitis and photophobia are the most uncomplicated reported presentations. Moreover, MPXV can manifest as eye redness, frontal headache, orbital and peri-ocular rashes, lacrimation and ocular discharge, subconjunctival nodules and, less frequently, as keratitis, corneal ulceration, opacification, perforation and blindness. The ocular manifestations have been less frequent and arguably less severe within the current outbreak. Despite the possibility of underestimation, the emerging evidence from observational investigations documented rates of around 1% for ocular involvement in the current outbreak compared to a 9–23% incidence in previous outbreaks in the endemic countries. The history of smallpox immunization is a protective factor against these complications. Despite a lack of definite and established treatment, simple therapies like regular lubrication and prophylactic use of topical antibiotics may be considered for MPXV ocular complications. Timely administration of specific antivirals may also be effective in severe cases. Monkeypox usually has mild to moderate severity and a self-limited course. However, timely recognition and proper management of the disease could reduce the risk of permanent ocular sequelae and disease morbidity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The ocular manifestations of monkeypox are uncommon and encompass a spectrum of symptoms from eyelid/periorbital lesions, blepharoconjunctivitis and keratitis to corneal scarring and blindness. |

The ocular involvement in the ongoing outbreak seems to be rarer and to cause fewer permanent sequels compared to historical outbreaks. |

While there is no definite treatment for ocular manifestations, oral tecovirimat is the mainstay of options, and trifluridine eye drops, antibiotics, steroids, vitamins and other antivirals may be effective. |

Due to a higher risk for more severe complications in unvaccinated individuals, encouraging high-risk populations to take vaccines through promoting public awareness is of great importance. |

Introduction

Monkeypox virus (MPXV) is an etiological agent of zoonotic disease endemic to central and West Africa [1]. Considered a high-consequence infectious disease (HCID) [2], it presents as a smallpox-like disease with cutaneous rashes and fever but with substantially lower mortality [3]. Since the termination of the worldwide smallpox vaccination program in the 1970s, several outbreaks of increasing scale have occurred in endemic areas [4, 5]. The first evidence of MPXV presence in non-African countries dates back to the US cases in 2003, where the virus spillover occurred from infected mammals [6, 7]. Since then, multiple countries outside Africa have reported cases linked with endemic areas. Even though the virus dissemination predominantly occurs via human-to-animal exposure, it could also spread between humans [8]. It is known that the virus is transmitted mainly through contact with body fluids, skin lesions, respiratory droplets and contaminated clothing of infected individuals [9].

The 2022 MPXV outbreak in non-endemic countries has puzzled scientists around the world regarding the possibility of containing the outbreak and unusual transmission in the population of men who have sex with men (MSM). This multi-country outbreak initiated in the UK has spread to more than 50 countries predominantly in Europe [10]. Current disease manifestations are rather atypical compared to previous outbreaks, including anogenital rashes and milder prodrome. Therefore, it has been proposed that the case definition should be revised as we are becoming more vigilant about virus behavior [11, 12].

It is imperative for ophthalmologists to be familiar with the ocular manifestations of MPXV disease. Therefore, the present review discusses all reported ocular manifestations to date.

Ocular Symptoms of Monkeypox

Methods and Literature Search

We conducted a comprehensive search in online databases of PubMed and Scopus using the key terms related to: [monkeypox, monkeypox virus, ‘monkey pox’, MPXV] AND [eyelid, blepharitis, palpebral, lacrimal, corneal, keratitis, keratopathy, conjunctivitis, uveal, uveitis, scleritis, episcleritis, iritis, iridocyclitis, ‘pars planitis’, choroiditis, chorioretinitis, retinitis, papillitis, retinal, dacryoadenitis, cataract, glaucoma, endophthalmitis, orbital, optic, ocular, eye, peri-ocular, intraocular, photophobia, ophthalmic, visual, blindness]. No restrictions of language or record types were applied. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

General Manifestations

As the illness progresses toward different stages, the infection affects multiple organs and anatomical sites. The typical disease manifestation begins with viral prodrome that lasts 2–3 days and predominantly with fever and, to a lesser extent, other constitutional symptoms, including asthenia, headache, myalgia, lymphadenopathy, chills and sweats [3, 13]. The presence of lymphadenopathy discriminates against other differential diagnoses, including smallpox [14, 15]. After prodromal resolution, these symptoms are replaced by maculopapular rashes in centrifugal patterns with different stages of evolution and could affect mucosal membranes and ocular surfaces. However, in the 2022 clusters of infections, the rashes are appearing on sites (anogenital regions) linked to sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and possibly raise this concern for MPXV [11, 16]. Moreover, the atypical signs of rash initiation before fever and short-lived or absent prodrome phase in some cases could imply that the current outbreak requires more advanced surveillance for case definition and categorizing patients with different clinical suspicions [11].

Besides the acute phase of the disease that typically lasts 2–4 weeks, the viral infection could contribute to prolonged disease or long-term complications, particularly in vulnerable groups with compromised immune systems. These sequels consist of bronchopneumonia, encephalitis, ocular surface involvements and secondary bacterial infections imposed on primary lesions [17, 18].

Ocular Complications

The 2022 Monkeypox Outbreak

As the current outbreak continues, less common ocular manifestations are being reported worldwide; still, the scale of the outbreak has not reached a sufficient point to conduct robust investigations on the evolution of rare symptoms. Regarding the present outbreak, these ophthalmic complications have been rarely (< 1%) [19] reported in the cases from 27 EU/EEA countries (> 20,000 cases as of 27 September 2022), while this profile has been higher in the endemic countries varying from 9 to 23% [20]. Other studies in the current outbreak reported a quite similar incidence of MPXV ocular complications, 2 out of 197 cases in London (1%) [21], 2 out of 185 cases in Spain (1.1%) [22] and 2 out of 264 cases in France (0.8%) [23].

One of the first documentations of ocular involvement in the recent outbreak dates to a case series performed in international cases from April to June 2022 across 16 countries. Among 528 subjects, three patients had conjunctival lesions, which led to hospitalization in two of them [24]. In line with this study, a case series on 264 subjects from France reported ocular involvement in two patients who were hospitalized afterward, considering ocular involvement a severe form of the disease [25]. The ocular manifestations, treatments received and ultimate picture of the MPXV-infected cases during the 2022 outbreak are summarized in Table 1.

Previous Outbreaks

Human Studies

The MPXV ophthalmic involvement may vary from subtle to sight-threatening symptoms. The most frequent and uncomplicated ocular manifestations are blepharitis and conjunctivitis [18, 26]. Patients with conjunctivitis encountered a higher frequency of constitutional symptoms and light sensitivity and had a higher tendency to become bedridden (47%) compared to those without (17%) [27]. It could imply that conjunctivitis might be associated with more severe forms of the disease and a predictor of the disease course. Moreover, the investigation of the 2003 US outbreak as the first document of MPXV in the western hemisphere reported blepharitis in 9% of patients who had direct exposure to infected pets [7]. Preauricular lymphadenopathy and frontal headache affecting orbits have also been reported [20].

The protective effect of smallpox vaccination for MPXV corneal lesions is reflected in World Health Organization (WHO) enhanced surveillance in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) from 1981 to 1986. The risks of these serious sequels were higher in younger children and in individuals who contracted the virus from animal exposure [28].

The above findings highlight the prominence of risk stratification in susceptible individuals, particularly unvaccinated children, and the necessity of identifying possible MPXV ocular symptoms to prevent them from further progression to permanent sequelae. Due to scarce evidence on ocular disease progression and pattern of symptoms in MPXV infection, it is crucial for further research to shed light on more detailed symptomatology. The ocular manifestations, management and outcomes of MPXV cases within the previous outbreaks are summarized in Table 2.

Animal Studies

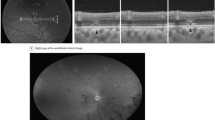

The study of MPXV ocular symptoms and viral presence in ocular tissues initially came from infected prairie dogs (Cynomys ludovicianus) in close contact with African rodents in the 2003 Wisconsin outbreak [7]. Some of these animals were reported to have ocular discharge and necrotizing blepharoconjunctivitis, which was the first symptom of the illness; it made the eyeballs swollen and damaged the cornea and conjunctiva in a multifocal pattern [29, 30].

Furthermore, an animal model for MPXV infection with Gambian Pouched Rats (Cricetomys gambianus) illustrated that after 14 days of virus inoculation through the dermal or nasal route, corneal injuries emerged with unilateral white-yellow opacity and ocular discharge. Additionally, viral shedding from ocular mucosa started 7 days after inoculation and was positive until day 21 post-inoculation [31]. In parallel, the viral DNA detection in ocular swabs was confirmed as early as 9 days post-exposure in a study on a prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus) model that inoculated animals with two viral clades of West Africa and Congo Basin via similar routes to the former study [32].

Differential Diagnosis of Monkeypox

Despite MPXV ocular damage, other orthopoxviruses and their vaccination contribute to similar corneal infections and complications. One of the most rigorously investigated poxviruses is smallpox. Lymphadenopathy, present primarily in the early stages of the MPXV infection, is the core factor differentiating MPXV, smallpox and chickenpox infection [14]. Ocular manifestations have been reported in 5–9% of smallpox cases, and from its shared features with MPXV, corneal ulceration is the most frequent sequel that further threatens the vision by several routes such as perforation and endophthalmitis [33].

Ocular vaccinia should be suspected in a patient with pustular lesions on the eyelid or conjunctiva with a recent immunization history or recent contact with a smallpox vaccine recipient [34, 35]. Blepharoconjunctivitis is caused by accidental eye rubbing after touching the active smallpox immunization site by the vaccinee (autoinoculation) or close contact [34, 36]. The incidence of ocular vaccinia following smallpox vaccination is about 10 to 20 cases per 1 million primary immunizations, and it is associated with more complications compared with revaccinated cases [33]. While the risk of this event was estimated to be the same between the two traditional smallpox vaccines, Dryvax, also known as ACAM2000 [37], the newly approved non-replicating vaccine for smallpox, and MPXV, MVA-BN (Modified Vaccinia Ankara-Bavarian Nordic) vaccine, do not lead to the development of ocular vaccinia.

Herpes simplex virus (HSV), varicella zoster virus (VZV), and Molluscum contagiosum (MC) infections can also mimic the ocular presentations of orthopoxviruses. The primary ocular HSV-1 infection is mainly asymptomatic, while it can still resemble MPXV ocular manifestations by presenting with blepharoconjunctivitis and superficial punctate keratitis (SPKs) [38]. Moreover, the recurrent HSV ocular characteristics fall into three major categories; keratitis, uveitis and retinitis. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus is caused by the reactivation of latent VZV, and diagnosis should be focused on a history of previous rash or skin findings [39]. It can mimic ocular forms of poxviruses by causing conjunctivitis, epithelial keratitis and anterior corneal infiltrates [40, 41]. MC, caused by a virus from the poxvirus family, is characterized by skin or mucosal papular eruptions (usually 2–6 mm) with a white pearly caseous substance in the center [42] that can occasionally afflict the eyes. They most commonly appear on eyelids and can progress further to cause follicular conjunctivitis, keratitis and rarely pannus [43, 44].

Management of Ocular Complications

Decades before smallpox eradication, eye-protective measures were limited to the application of ophthalmic lubricants and intake of systemic vitamin supplementation to prevent secondary bacterial infections with potential catastrophic complications, including corneal ulceration, perforation, anterior staphyloma and phthisis bulbi [45]. Later on and amid the smallpox mass vaccination, topical antivirals, including idoxuridine, trifluridine and vidarabine, were used to treat or prevent cornea or conjunctiva involvement as in ocular vaccinia or ocular smallpox [33].

On the other hand, trifluorothymidine (trifluridine), an anti-herpesvirus fluorinated pyrimidine nucleoside that inhibits viral DNA synthesis, has been used more frequently. Although its efficacy has not been supported by any clinical trial yet, some evidence from case reports and animal studies supports its use in ocular vaccinia keratitis and conjunctivitis [46]. Among several cases with inadvertent ocular inoculation of orthopoxviruses [34, 47], trifluridine has shown a favorable effect in alleviating the symptoms and preventing permanent scarring. However, some case reports found it ineffective for treating acute ocular complications of cowpox and another orthopox virus [48, 49]. WHO recommends it for the management of monkeypox ocular complications [50]. Prophylactic use may hinder the deterioration of palpebral and peri-ocular to conjunctival and/or corneal lesions [51].

Oral or systemic antibiotics may be considered for treatment or prophylaxis in ocular MPXV as was indicated for prophylaxis against ocular vaccinia bacterial superinfection in the presence of keratitis [34].

Topical steroids may prevent monkeypox keratitis or iritis [50]. However, concurrent use of steroids with topical antivirals should be considered. Otherwise, the viral clearance from the eye may take longer [52]. Topical steroids may be considered for reducing inflammation in severe keratitis only when the corneal epithelium is intact and the active infection is resolved, in conjunction with antiviral therapies. Besides, vaccinia immune globulin (VIG) may be considered for administration in severe ocular complications. Still, its use should be limited or weighed carefully in the presence of keratitis to avoid potential corneal scarring, probably through the aggregation of antigen-antibody complexes [33, 34].

Clinicians should abstain from administering aciclovir and ganciclovir for monkeypox treatment as they are effective herpesviruses and not orthopoxviruses [53]. Despite a lack of clinical trials on the safety and efficacy of Monkeypox antivirals, they shall be used under expanded access protocols, including Monitored Emergency Use of Unregistered and Investigational Interventions [50].

Oral tecovirimat (600 mg two times per day for 2 weeks), an inhibitor of the viral envelope protein VP37, is the most prominent of these antivirals. It is recommended for severe forms of the disease, such as patients with ocular or periorbital manifestations [54]. Tecovirimat is approved by the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of monkeypox and in the USA, Canada and Europe for human smallpox disease. Nonetheless, it is still not FDA-approved for monkeypox treatment [54]. Administration of tecovirimat for 5–7 days in monkeypox animal models has shown promising clinical and virological outcomes, yet the duration of treatment is still higher in humans due to suspicion of an early rebound following a premature cessation of the treatment [53].

In vitro and animal investigations have shown cidofovir and its prodrug to be also effective against orthopoxviruses [50]. Prolonged use of cidofovir in HIV-related cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis can help the development of anterior uveitis with hypotony. It does not necessarily indicate the termination of treatment [55].

Apart from antivirals and antibiotics, steroids and vitamins may also be effective. Vitamin A supplement could be considered for the malnourished as it helps the wound-healing process [50].

Discussion

Monkeypox has been a widely neglected virus for a very long time. The very recent outbreak of the virus in non-endemic areas has raised considerable concern regarding the disease's short- and long-term complications. There is a vast knowledge gap regarding monkeypox ocular symptoms, long-term complications and therapeutics. Much of the data on the MPXV ocular signs and symptoms come from sporadic case reports, and further studies should be directed at outstanding clinical trials and original investigations. The ocular complications of the MPXV cases during the 2022 outbreak are representative of a potential shift in frequency and pattern. Although it is yet too premature to confirm this statement, the recent cases were indicative of less frequent [56] and more subtle and self-limited symptoms [56,57,58,59,60] than in previous outbreaks in endemic countries [14, 15, 18, 28, 61] and rarely resulted in permanent sequelae.

Based on the present data, MPXV can manifest as eye redness, photophobia, frontal headache, orbital and peri-ocular vesicular and pustular rashes, blepharitis, lacrimation, ocular discharge, conjunctivitis, subconjunctival nodules, keratitis and subsequent corneal ulceration, opacification, perforation and blindness. These complications may occur more frequently and devastatingly in those without prior immunization against smallpox.

Occasionally, the corneal, conjunctival and eyelid involvement in monkeypox infection is a bacterial rather than a directly toxic viral phenomenon and thus may respond quickly to antibiotics [11]. A negative monkeypox DNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from the ocular samples may raise suspicion of a bacterial infection [11].

It is still unclear whether the ocular involvement is a result of the systemic spread of the virus in the early viremic phase of infection or is secondary to self-inoculation. Interestingly, it has been demonstrated that smallpox, a similar virus from the pox family, can be actively secreted into tears and thus play a role in the spread of the disease [62]. Hence, it is crucial to note that conjunctivitis could serve as a path of disease propagation, particularly when preceding cutaneous lesions [63]. Comparing the positive results of monkeypox DNA PCR from ocular and cutaneous swabs, the more prolonged clearance of the virus from the ocular than cutaneous lesions may contribute to longer disease transmissibility [56]. Despite some hypotheses regarding the passage of MPXV into the conjunctival secretions via the plasma compartment, the emergence of cutaneous lesions before ocular involvement may suggest self-inoculation as the culprit [56]. A case described by Meduri et al. also raised this hypothesis as two separate PCR tests from ocular and cutaneous samples had close cycle threshold values, suggesting a transmission via eye contact [64]. Accordingly, healthcare professionals should be extra vigilant and recruit appropriate preventive measures.

Regarding treatment, monkeypox is mostly a mild to moderate self-limited entity. Hence, there is no need for the proactive use of antivirals for disease containment [24]. Nonetheless, in severe cases or when the lesions are located at sensitive sites like ocular involvement, administration of specific antivirals may be indicated [65]. For MPXV ocular complications, simple therapies like regular lubrication and prophylactic use of topical antibiotics should be considered [45].

Severe sequelae and sight-threatening complications tend to occur more in unvaccinated individuals (74%) than in vaccinated populations (39.5%) [20]. Thus, encouraging people to take vaccines by promoting public awareness is of paramount importance.

References

di Giulio DB, Eckburg PB. Human monkeypox: an emerging zoonosis. Lancet Infect Dis [Internet]. 2004 ;4(1):15–25. Available from: http://www.thelancet.com/article/S1473309903008569/fulltext. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

High consequence infectious diseases (HCID)—GOV.UK [Internet]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/high-consequence-infectious-diseases-hcid. cited 18 Jul 2022.

Wilson ME, Hughes JM, McCollum AM, Damon IK. Human monkeypox. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2014 ;58(2):260–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24158414/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Bunge EM, Hoet B, Chen L, Lienert F, Weidenthaler H, Baer LR, et al. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox-A potential threat? A systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2022;16(2). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35148313/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Beer EM, Bhargavi Rao V. A systematic review of the epidemiology of human monkeypox outbreaks and implications for outbreak strategy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2019;13(10). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31618206/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Multistate Outbreak of Monkeypox—Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin, 2003. JAMA. 2003;290(1):30.

Reed KD, Melski JW, Graham MB, Regnery RL, Sotir MJ, Wegner M v., et al. The detection of monkeypox in humans in the Western Hemisphere. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2004;350(4):342–50. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14736926/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Nolen LD, Osadebe L, Katomba J, Likofata J, Mukadi D, Monroe B, et al. Extended human-to-human transmission during a Monkeypox outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2016;22(6):1014–21. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27191380/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

How it Spreads | Monkeypox | Poxvirus | CDC [Internet]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/transmission.html. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Global.health|Map [Internet]. Available from: https://map.monkeypox.global.health/country. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Adler H, Gould S, Hine P, Snell LB, Wong W, Houlihan CF, et al. Clinical features and management of human monkeypox: a retrospective observational study in the UK. Lancet Infect Dis [Internet]. 2022; Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35623380/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Pan D, Sze S, Nazareth J, Martin CA, Al-Oraibi A, Baggaley RF, et al. Monkeypox in the UK: arguments for a broader case definition. Lancet [Internet]. 2022;399(10344):2345–6. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35716671/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Ogoina D, Izibewule JH, Ogunleye A, Ederiane E, Anebonam U, Neni A, et al. The 2017 human monkeypox outbreak in Nigeria-Report of outbreak experience and response in the Niger Delta University Teaching Hospital, Bayelsa State, Nigeria. PLoS One [Internet]. 2019;14(4). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30995249/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Ježek Z, Szczeniowski M, Paluku KM, Mutombo M. Human monkeypox: clinical features of 282 patients. J Infect Dis [Internet]. 1987;156(2):293–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3036967/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Damon IK. Status of human monkeypox: clinical disease, epidemiology and research. Vaccine [Internet]. 2011;29 Suppl 4(Suppl. 4). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22185831/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Heskin J, Belfield A, Milne C, Brown N, Walters Y, Scott C, et al. Transmission of monkeypox virus through sexual contact - A novel route of infection. J Infect [Internet]. 2022; Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35659548/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Huhn GD, Bauer AM, Yorita K, Graham MB, Sejvar J, Likos A, et al. Clinical characteristics of human monkeypox, and risk factors for severe disease. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2005;41(12):1742–51. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16288398/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Learned LA, Reynolds MG, Wassa Wassa D, Li Y, Olson VA, Karem K, et al. Extended interhuman transmission of Monkeypox in a hospital community in the Republic of the Congo, 2003. Am J Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 2005;73(2):428–34. Available from: https://www.ajtmh.org/view/journals/tpmd/73/2/article-p428.xml. Cited 3 Aug 2022.

Monkeypox situation update, as of 4 October 2022 [Internet]. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/monkeypox-situation-update. Cited 9 Oct 2022.

Abdelaal A, Serhan HA, Mahmoud MA, Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Sah R. Ophthalmic manifestations of monkeypox virus. Eye (Lond) [Internet]. 2022; Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35896700/. Cited 9 Oct 2022.

Patel A, Bilinska J, Tam JCH, da Silva FD, Mason CY, Daunt A, et al. Clinical features and novel presentations of human monkeypox in a central London centre during the 2022 outbreak: descriptive case series. The BMJ. 2022;378:e072410.

Català A, Clavo‐Escribano P, Riera‐Monroig J, Martín‐Ezquerra G, Fernandez‐Gonzalez P, Revelles‐Peñas L et al. Monkeypox outbreak in Spain: clinical and epidemiological findings in a prospective cross‐sectional study of 185 cases. Brit J Dermatol [Internet]. 2022;187(5):765–72. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.21790. Cited 7 Nov 2022.

Mailhe M, Beaumont AL, Thy M, le Pluart D, Perrineau S, Houhou-Fidouh N, et al. Clinical characteristics of ambulatory and hospitalized patients with monkeypox virus infection: an observational cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2022.08.012.

Thornhill JP, Barkati S, Walmsley S, Rockstroh J, Antinori A, Harrison LB, et al. Monkeypox virus infection in humans across 16 countries—April–June 2022. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2022;387(8):679–91. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35866746/. Cited 9 Oct 2022.

Mailhe M, Beaumont AL, Thy M, le Pluart D, Perrineau S, Houhou-Fidouh N, et al. Clinical characteristics of ambulatory and hospitalized patients with monkeypox virus infection: an observational cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect [Internet]. 2022; Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36028090/. Cited 9 Oct 2022.

Jezek Z, Grab B, Szczeniowski M V., Paluku KM, Mutombo M. Human monkeypox: secondary attack rates. Bull World Health Organ [Internet]. 1988;66(4):465. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC2491159/?report=abstract. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Hughes C, McCollum A, Pukuta E, Karhemere S, Nguete B, Lushima RS, et al. Ocular complications associated with acute monkeypox virus infection, DRC. Int J Infect Dis [Internet]. 2014;21:276–7. Available from: http://www.ijidonline.com/article/S1201971214010534/fulltext. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Jezek Z, Grab B, Szczeniowski M, Paluku KM, Mutombo M. Clinico-epidemiological features of monkeypox patients with an animal or human source of infection. Bull World Health Organ [Internet]. 1988 ;66(4):459. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC2491168/?report=abstract. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Tack DM, Reynolds MG. Zoonotic poxviruses associated with companion animals. Animals (Basel) [Internet]. 2011;1(4):377–95. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26486622/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Langohr IM, Stevenson GW, Thacker HL, Regnery RL. Extensive lesions of monkeypox in a prairie dog (Cynomys sp). Vet Pathol [Internet]. 2004;41(6):702–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15557083/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Falendysz EA, Lopera JG, Lorenzsonn F, Salzer JS, Hutson CL, Doty J, et al. Further assessment of monkeypox virus infection in Gambian pouched rats (Cricetomys gambianus) using in vivo bioluminescent imaging. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2015;9(10):1–19. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26517839/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Hutson CL, Olson VA, Carroll DD, Abel JA, Hughes CM, Braden ZH, et al. A prairie dog animal model of systemic orthopoxvirus disease using West African and Congo Basin strains of monkeypox virus. J Gen Virol [Internet]. 2009;90(Pt 2):323–33. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19141441/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Semba RD. The ocular complications of smallpox and smallpox immunization. Arch Ophthalmol [Internet]. 2003;121(5):715–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12742852/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Montgomery JR, Carroll RB, McCollum AM. Ocular vaccinia: a consequence of unrecognized contact transmission. Mil Med [Internet]. 2011;176(6):699–701. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21702392/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Hu G, Wang MJ, Miller MJ, Holland GN, Bruckner DA, Civen R, et al. Ocular vaccinia following exposure to a smallpox vaccinee. Am J Ophthalmol [Internet]. 2004;137(3):554–6. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15013881/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Baynham JTL, Newman SA. Ocular vaccinia with severe restriction of extraocular motility. Arch Ophthalmol [Internet]. 2009;127(12):1688–90. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20008731/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Tack DM, Karem KL, Montgomery JR, Collins L, Bryant-Genevier MG, Tiernan R, et al. Unintentional transfer of vaccinia virus associated with smallpox vaccines: ACAM2000(®) compared with Dryvax(®). Hum Vaccin Immunother [Internet]. 2013;9(7):1489–96. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23571177/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Barker NH. Ocular herpes simplex. BMJ Clin Evid [Internet]. 2008;2008. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC2907955/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Catron T, Hern HG. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Western J Emerg Med [Internet]. 2008;9(3):174. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC2672268/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Liesegang TJ. Corneal complications from herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Ophthalmology [Internet]. 1985;92(3):316–24. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3873048/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Liesegang TJ. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus natural history, risk factors, clinical presentation, and morbidity. Ophthalmology [Internet]. 2008;115(2 Suppl). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18243930/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Charteris DG, Bonshek RE, Tullo AB. Ophthalmic molluscum contagiosum: clinical and immunopathological features. Br J Ophthalmol [Internet]. 1995;79(5):476–81. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7612562/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Serin Ş, Oflaz AB, Karabağlı P, Gedik Ş, Bozkurt B. Eyelid molluscum contagiosum lesions in two patients with unilateral chronic conjunctivitis. Turk J Ophthalmol [Internet]. 2017;47(4):226–30. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28845328/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Mathur SP. Ocular complications in molluscum contagiosum. Br J Ophthalmol [Internet]. 1960;44(9):572–3. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/13768154/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Reynolds MG, McCollum AM, Nguete B, Lushima RS, Petersen BW. Improving the care and treatment of monkeypox patients in low-resource settings: applying evidence from contemporary biomedical and smallpox biodefense research. Viruses [Internet]. 2017;9(12). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29231870/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Altmann S, Brandt CR, Murphy CJ, Patnaikuni R, Takla T, Toomey M, et al. Evaluation of therapeutic interventions for vaccinia virus keratitis. J Infect Dis [Internet]. 2011;203(5):683–90. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21278209/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Lewis FS, Norton SA, Bradshaw RD, Lapa J, Grabenstein JD. Analysis of cases reported as generalized vaccinia during the US military smallpox vaccination program, December 2002 to December 2004. J Am Acad Dermatol [Internet]. 2006;55(1):23–31. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16781288/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Kinnunen PM, Holopainen JM, Hemmilä H, Piiparinen H, Sironen T, Kivelä T, et al. Severe Ocular Cowpox in a Human, Finland. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2015;21(12):12–21. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26583527/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Graef S, Kurth A, Auw-Haedrich C, Plange N, Kern W v., Nitsche A, et al. Clinicopathological findings in persistent corneal cowpox infection. JAMA Ophthalmol [Internet]. 2013;131(8):1089–91. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23765283/. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Clinical management and infection prevention and control for monkeypox: Interim rapid response guidance, 10 June 2022 [Internet]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MPX-Clinical-and-IPC-2022.1. Cited 13 Oct 2022.

Reynolds MG, McCollum AM, Nguete B, Lushima RS, Petersen BW. Improving the care and treatment of monkeypox patients in low-resource settings: applying evidence from contemporary biomedical and smallpox biodefense research. Viruses. 2017;9:380.

Graef S, Kurth A, Auw-Haedrich C, Plange N, Kern WV, Nitsche A, et al. Clinicopathological findings in persistent corneal cowpox infection. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131:1089–91.

Milligan AL, Koay SY, Dunning J. Monkeypox as an emerging infectious disease: the ophthalmic implications. Brit J Ophthalmol [Internet]. 2022;bjo-2022–322268. Available from: https://bjo.bmj.com/lookup/doi/https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo-2022-322268. Cited 13 Oct 2022.

Guidance for Tecovirimat Use | Monkeypox | Poxvirus | CDC [Internet]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/Tecovirimat.html. Cited 13 Oct 2022.

Akler ME, Johnson DW, Burman WJ, Johnson SC. Anterior uveitis lovirus retinitis. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(4):651–7.

V M, A M, F C, F B, R S, S M, et al. Ocular involvement in monkeypox: description of an unusual presentation during the current outbreak. J Infect [Internet]. 2022; Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35987391/. Cited 9 Oct 2022.

Jarman EL, Alain M, Conroy N, Omam LA. A case report of monkeypox as a result of conflict in the context of a measles campaign. Public Health Pract (Oxf) [Internet]. 2022;4. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36133748/. Cited 9 Oct 2022.

Foos W, Wroblewski K, Ittoop S. Subconjunctival nodule in a patient with acute monkeypox. JAMA Ophthalmol [Internet]. 2022; Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36069930/. Cited 9 Oct 2022.

Scandale P, Raccagni AR, Nozza S. Unilateral Blepharoconjunctivitis due to monkeypox virus infection. Ophthalmology [Internet]. 2022; Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36041955/. Cited 9 Oct 2022.

Benatti SV, Venturelli S, Comi N, Borghi F, Paolucci S, Baldanti F. Ophthalmic manifestation of monkeypox infection. Lancet Infect Dis [Internet]. 2022;22(9):1397. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35914539/. Cited 9 Oct 2022.

Hutson CL, Lee KN, Abel J, Carroll DS, Montgomery JM, Olson VA, et al. Monkeypox zoonotic associations: insights from laboratory evaluation of animals associated with the multi-state us outbreak. Am J Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 2007;76(4):757–68. Available from: https://www.ajtmh.org/view/journals/tpmd/76/4/article-p757.xml. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Sarkar JK, Mitra AC, Mukherjee MK, De SK, Mazumdar DG. Virus excretion in smallpox: 1. Excretion in the throat, urine, and conjunctiva of patients. Bull World Health Organ [Internet]. 1973;48(5):517. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC2482928/?report=abstract. Cited 18 Jul 2022.

Ly-Yang F, Miranda-Sánchez A, Burgos-Blasco B, Fernández-Vigo JI, Gegúndez-Fernández JA, Díaz-Valle D. Conjunctivitis in an individual with monkeypox. JAMA Ophthalmol [Internet]. 2022; Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36069834/. Cited 9 Oct 2022.

Meduri E, Malclès A, Kecik M. Conjunctivitis with monkeypox virus positive conjunctival swabs. Ophthalmology [Internet]. 2022;129(10). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35973854/. Cited 9 Oct 2022.

Rizk JG, Lippi G, Henry BM, Forthal DN, Rizk Y. Prevention and treatment of monkeypox. Drugs [Internet]. 2022 ;82(9):957–63. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35763248/. Cited 9 Oct 2022.

Cash-Goldwasser S, Labuda SM, McCormick DW, Rao AK, McCollum AM, Petersen BW, et al. Ocular monkeypox—United States, July–September 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2022;71(42):1343–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36264836/. Cited 7 Nov 2022.

Rai RS, Kahan E, Hirsch B, Udell I, Hymowitz M. Ocular pox lesions in a male patient with monkeypox treated with tecovirimat. JAMA Ophthalmol [Internet]. 2022; Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36326736/. Cited 7 Nov 2022.

Alexis J, Hohnen H, Kenworthy M, Host BKJ. Ocular manifestation of monkeypox virus in a 38-year old Australian male. IDCases [Internet]. 2022;30:e01625. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2214250922002530. Cited 9 Nov 2022.

Ogoina D, Iroezindu M, James HI, Oladokun R, Yinka-Ogunleye A, Wakama P, et al. Clinical course and outcome of human monkeypox in Nigeria. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2020;71(8):E210–4. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32052029/. Cited 9 Oct 2022.

Whitehouse ER, Bonwitt J, Hughes CM, Lushima RS, Likafi T, Nguete B, et al. Clinical and epidemiological findings from enhanced monkeypox surveillance in Tshuapa Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo during 2011–2015. J Infect Dis [Internet]. 2021;223(11):1870–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33728469/. Cited 9 Oct 2022.

Formenty P, Muntasir MO, Damon I, Chowdhary V, Opoka ML, Monimart C, et al. Human monkeypox outbreak caused by novel virus belonging to Congo Basin Clade, Sudan, 2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16(10):1539.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Author Contributions

Kiana Hassanpour framed the idea of the study, and Amirmasoud Rayati Damavandi and Farbod Semnani contributed equally to searching databases and drafting the manuscript. Kiana Hassanpour critically revised the manuscript. All authors have read and confirmed the content of the manuscript for publication.

Disclosures

Amirmasoud Rayati Damavandi, Farbod Semnani and Kiana Hassanpour have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rayati Damavandi, A., Semnani, F. & Hassanpour, K. A Review of Monkeypox Ocular Manifestations and Complications: Insights for the 2022 Outbreak. Ophthalmol Ther 12, 55–69 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40123-022-00626-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40123-022-00626-4