Abstract

Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (AHSCT) has been used in the treatment of highly active multiple sclerosis (MS) for over two decades. It has been demonstrated to be highly efficacious in relapsing–remitting (RR) MS patients failing to respond to disease-modifying drugs (DMDs). AHSCT guarantees higher rates of no evidence of disease activity (NEDA) than those achieved with any other DMDs, but it is also associated with greater short-term risks which have limited its use. In the 2019 updated EBMT and ASBMT guidelines, which review the clinical evidence of AHSCT in MS, AHSCT indication for highly active RRMS has changed from “clinical option” to “standard of care”. On this basis, AHSCT must be proposed on equal footing with second-line DMDs to patients with highly active RRMS, instead of being considered as a last resort after failure of all available treatments. The decision-making process requires a close collaboration between transplant hematologists and neurologists and a full discussion of risk–benefit of AHSCT and alternative treatments. In this context, we propose a standardized protocol for decision-making and informed consent process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Some patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) still experience disease activity despite treatment with highly efficacious disease-modifying drugs (DMDs). |

Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (AHSCT) guarantees higher rates of no evidence of disease activity (NEDA) than those achieved with any other DMDs, but it is also associated to greater short-term risks which have limited its use. |

The 2019 updated EBMT and ASBMT guidelines change the AHSCT indication for highly active RRMS from “clinical option” to “standard of care”; thus AHSCT should be proposed to these patients on equal footing with second-line DMDs. |

Here we propose a standardized protocol for a decision-making and informed consent process implemented at our center. |

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a heterogeneous inflammatory disease affecting the central nervous system (CNS), in which a deep immunological alteration gives rise to pathologic phenomena leading to the progressive and irreversible degeneration of the CNS [1].

Significant therapeutic advances have been made in recent decades, and more than a dozen disease-modifying drugs (DMDs) have been approved for treatment of relapsing–remitting (RR) MS. Based on the approval of authorities such as the European Medicines Agency (EMA), DMDs are usually differentiated into first-line drugs (interferon beta-1b, interferon beta-1a -sc, im-, peginterferon beta-1a, glatiramer acetate, teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate) and second-line drugs (cladribine, fingolimod, natalizumab, ocrelizumab and alemtuzumab), which differ in their effectiveness, safety profile and route of administration [2]. The second-line treatments are recommended for patients with an active course of MS who failed to respond to the first line. The European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS), the European Academy of Neurology (EAN) and the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) have developed guidelines to support neurologists in the pharmacological treatment of patients affected by MS and to enable homogeneity of treatment decisions across countries [3, 4].

The majority of DMDs are administered repeatedly with a long-term maintenance approach, which has implications in terms of patient compliance, risk of complications and health cost [5]. DMD costs account for most of the direct healthcare costs in MS. They have rapidly risen in the past few years and are expected to further increase among overall expenses, to the point where some studies estimate them to be beyond the health care system tolerance or the generally accepted cost-effectiveness thresholds [6, 7]. Some DMDs have been proven highly efficacious, at the expense of potential life-threatening side effects, e.g. progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) for natalizumab, the important lymphopenia for cladribine, ocular disorders for fingolimod, and the increased risk of pulmonary hemorrhages, heart attacks, strokes and cervical-cephalic arterial dissection for alemtuzumab [2, 7]. DMD treatment reduces the number of relapses and progression of disability in the short term, and an emerging corpus of data suggests that the onset of a secondary progressive phase can also be delayed [8, 9]. However, some patients still have ongoing disease activity despite treatment with newer, highly efficacious DMDs, with no evidence of disease activity (NEDA) rates lower than 50% at 2 years [10, 11].

Ablation of the immune system followed by autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (AHSCT) for the treatment of MS has been explored for approximately two decades since the original pivotal report of its feasibility [12]. AHSCT is a once-only treatment whose therapeutic effect could last for many years; thus it might represent a cost-saving opportunity compared with continuous treatment with DMDs [7, 13].

The European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Autoimmune Disease Working Party (ADWP) and the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (ASBMT) gather scientists, neurologists and hematologists, with the goal of registering HSCT activity and promoting multicenter retrospective studies and randomized controlled trials. To date, several registry studies and two prospective comparative trials have provided evidence that AHSCT is highly effective in suppressing inflammatory MS activity [14,15,16,17]. Two meta-analyses of studies on patients undergoing transplants since 1995 have agreed that AHSCT can induce long-term remission for RRMS patients [17, 18]. The main concern limiting the use of AHSCT is the mortality risk. However, treatment-related mortality (TRM), which was initially high (3.6%), has decreased to 0.3% in studies post-2005, thanks to the greater experience and the accreditation of centers, improvements in transplant techniques and optimization of patient selection [18]. Major complications of AHSCT are secondary to the immunosuppression, and include febrile neutropenia, sepsis, urinary infections and viral reactivations. Late adverse events have also been described, including infertility, malignancies and secondary autoimmune conditions. However, menstruation recovery and good pregnancy outcome have been described in women after AHSCT for autoimmune diseases [19, 20]. Also, long-term follow-up studies report an incidence of secondary malignancies comparable to other DMDs, and a rate of secondary autoimmune conditions significantly lower than some DMDs, such as alemtuzumab [16]. No cases of PML have been reported so far in the literature, including patients with high titers of John Cunningham virus (JCV) antibodies previously treated with natalizumab. On the other hand, NEDA rates 2 years after AHSCT exceed 70%, which is considerably higher than DMDs. This suggests that AHSCT has a more extensive effect on disease activity, especially considering that participants in AHSCT trials usually experience more aggressive disease than the participants in all the other clinical trials [10, 11]. Patients with the RR form, a low level of disability, and clinical and MRI signs of disease activity show the best benefit/risk ratio from AHSCT [11, 18].

Multidisciplinary guidelines have been published over the years to advise on the selection and management of patients based on clinical evidence and registry activity [21,22,23,24,25]. Since 2012, with the publication of the EBMT-ADWP guidelines defining AHSCT as a clinical option in RRMS [22], MS has appeared as the fastest-growing indication for AHSCT among autoimmune diseases. Given the rapidly accumulating evidence on the health benefits and risks balanced against the non-AHSCT options, in the most recent updated EBMT-ADWP and ASBMT guidelines, the indication for AHSCT has been revised [24, 25]. AHSCT is now recommended as a standard of care for highly active RRMS failing at least one line of DMD, as defined by the occurrence of two clinical relapses or a clinical relapse and MRI activity at different time points within the prior 12 months. For patients with aggressive RRMS who developed severe disability in the previous 12 months, AHSCT is considered a clinical option before failing a full course of DMD.

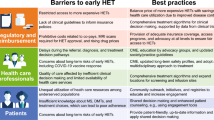

For years, AHSCT has been considered as a last resort after failure of all available treatments. Based on new EBMT and ASBMT guidelines, AHSCT should be proposed on equal footing with second-line DMDs to patients with highly active RRMS, particularly young patients with short disease duration and low Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score. However, several aspects deserve particular attention [24]. The setting of the AHSCT delivery should be transplant units accredited by JACIE [Joint Accreditation Committee ISCT-Europe] or equivalent and with close collaboration between neurologists and hematologists. Intermediate-intensity conditioning regimens are recommended. The informed consent process should include a full discussion of risk–benefit of AHSCT and alternative treatments with both neurologists and hematologists.

In this context, we have implemented a standardized protocol for the multidisciplinary decision-making and informed consent process for treatment of RRMS patients failing a second-line DMD. Step by step procedure is summarized in Fig. 1. This protocol gives patients the chance to choose a one-shot alternative treatment showing high rates of efficacy as against severe but rare short-term risks, which is in line with ECTRIMS/EAN guidelines recommending clinicians to engage patients in an ongoing dialogue regarding treatment decisions countries [3, 4].

To date, economic evaluations and cost-effectiveness analyses comparing AHSCT and different DMDs are lacking. However, based on our experience, we made an attempt to estimate the impact of AHSCT on the pharmaceutical cost burden to the Italian health care system. Since 2001, 11 RRMS patients have undergone AHSCT with intermediate-intensity conditioning regimens at our center, with a NEDA rate of 91% (median (range) follow-up: 58 months (6–224)). Considering a mean cost of €18,000 per year for therapy with DMDs, and a one-off cost of €38,000 for the AHSCT, the estimated savings amount to €611,000. This corresponds to 57% of the pharmaceutical spending expected for continuous treatment with DMDs for all patients throughout the same follow-up period. The cost savings would be much higher when considering that management costs for transplanted patients are low, and patients are likely to experience good quality of life in the long term. Although comparative clinical studies and health economic evaluations are necessary to lead decision-making, the evidence of a favorable cost-effectiveness ratio supports an increase in AHSCT delivery in the future.

References

Kutzelnigg A, Lassmann H. Pathology of multiple sclerosis and related inflammatory demyelinating diseases. 2014. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780444520012000029. Accessed 26 Nov 2019.

Dörr J, Paul F. The transition from first-line to second-line therapy in multiple sclerosis. Curr Treat Opt Neurol. 2015;17:354.

Montalban X, Gold R, Thompson AJ, Otero-Romero S, Amato MP, Chandraratna D, et al. ECTRIMS/EAN Guideline on the pharmacological treatment of people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2018;24:96–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458517751049.

Rae-Grant A, Day GS, Marrie RA, Rabinstein A, Cree BAC, Gronseth GS, et al. Practice guideline recommendations summary: disease-modifying therapies for adults with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2018;90:777–88. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000005347.

Hartung DM. The cost of multiple sclerosis drugs in the US and the pharmaceutical industry: too big to fail? Neurology. 2015;85:1728.

Hartung DM. Economics and cost-effectiveness of multiple sclerosis therapies in the USA. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14:1018–26.

Batcheller L, Baker D. Cost of disease modifying therapies for multiple sclerosis: is front-loading the answer? J Neurol. 2019;404:19–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2019.07.009.

Tramacere I, Del Giovane C, Salanti G, D’Amico R, Filippini G. Immunomodulators and immunosuppressants for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011381.pub2.

Brown JWL, Coles A, Horakova D, Havrdova E, Izquierdo G, Prat A, et al. Association of initial disease-modifying therapy with later conversion to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. JAMA. 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30644981. Accessed 26 Nov 2019.

Sormani MP, Muraro PA, Saccardi R, Mancardi G. NEDA status in highly active MS can be more easily obtained with autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation than other drugs. Mult Scler. 2017;23:201–4.

Muraro PA, Martin R, Mancardi GL, Nicholas R, Sormani MP, Saccardi R. Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for treatment of multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:391–405.

Fassas A, Anagnostopoulos A, Kazis A, Kapinas K, Sakellari I, Kimiskidis V, et al. Peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in the treatment of progressive multiple sclerosis: first results of a pilot study. Bone Marrow Transpl. 1997. https://www-nature-com.proxy.unimib.it/articles/1700944.pdf

Wang PTY, Burman BSJ, Farge MBD, Snowden JA. Evaluating the clinical effectiveness of autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation versus disease-modifying therapy in multiple sclerosis using a matching-adjusted indirect comparison: an exploratory study from the Autoimmune Diseases Working Party. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-019-0747-2.

Mancardi GL, Sormani MP, Gualandi F, Saiz A, Carreras E, Merelli E, et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in multiple sclerosis A phase II trial. 2015. https://n-neurology-org.proxy.unimib.it/content/neurology/84/10/981.full.pdf

Burt RK, Balabanov R, Burman J, Sharrack B, Snowden JA, Oliveira MC, et al. Effect of nonmyeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation vs continued disease-modifying therapy on disease progression in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321:165–74.

Muraro PA, Pasquini M, Atkins HL, Bowen JD, Farge D, Fassas A, et al. Long-term outcomes after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:459.

Ge F, Lin H, Li Z, Chang T. Efficacy and safety of autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in multiple sclerosis : a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol Sci. 2018;40:479–87.

Sormani MP, Muraro PA, Schiavetti I, Signori A, Laroni A, Saccardi R, et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Neurology. 2017;88:2115–22. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28455383

Maciejewska M, Snarski E, Wiktor-Jędrzejczak W. A preliminary online study on menstruation recovery in women after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant for autoimmune diseases. Exp Clin Transplant. 2016;14:665–9.

Snarski E, Snowden JA, Oliveira MC, Simoes B, Badoglio M, Carlson K, et al. Onset and outcome of pregnancy after autologous haematopoietic SCT (AHSCT) for autoimmune diseases: a retrospective study of the EBMT Autoimmune Diseases Working Party (ADWP). Bone Marrow Transpl. 2015;50:216–20. https://www.nature.com/articles/bmt2014248

Tyndall A, Gratwohl A. Blood and marrow stem cell transplants in auto-immune disease: a consensus report written on behalf of the European League against Rheumatism (EULAR) and the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). Bone Marrow Transpl. 1997;19:643–5.

Snowden JA, Saccardi R, Allez M, Ardizzone S, Arnold R, Cervera R, et al. Haematopoietic SCT in severe autoimmune diseases: updated guidelines of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2012;47:770–90.

Alexander T, Bondanza A, Muraro PA, Greco R, Saccardi R, Daikeler T, et al. SCT for severe autoimmune diseases: consensus guidelines of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation for immune monitoring and biobanking. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2015;50:173–80. https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2014.251.

Sharrack B, Saccardi R, Alexander T, Badoglio M, Burman J, Farge D, et al. Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation and other cellular therapy in multiple sclerosis and immune-mediated neurological diseases: updated guidelines and recommendations from the EBMT Autoimmune Diseases Working Party (ADWP) and the Joint Accreditation Committee of EBMT and ISCT (JACIE). Bone Marrow Transpl. 2019;55:283–306.

Cohen JA, Baldassari LE, Atkins HL, Bowen JD, Bredeson C, Carpenter PA, et al. Autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for treatment-refractory relapsing multiple sclerosis: position statement from the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30794930. Accessed 17 Apr 2019.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This work was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health (Bando ricerca finalizzata, grant number RF-2013-02357497). No funding or sponsorship was received for the publication of this study.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Antonio Bertolotto has received advisory board and/or speaker honoraria from Biogen, Novartis, Sanofi; grant support from Almirall, Biogen, Associazione San Luigi Gonzaga ONLUS, Fondazione per la Ricerca Biomedica ONLUS, Mylan, Novartis and the Italian Multiple Sclerosis Society; and is the Editor in Chief of this journal. Marco Capobianco has received advisory board and/or speaker honoraria from Merck Serono, Biogen, Sanofi Genzyme, Roche, Novartis, TEVA, Almirall. Serena Martire, Luca Mirabile, Marco De Gobbi and Daniela Cilloni have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Digital features

To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12416372.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

About this article

Cite this article

Bertolotto, A., Martire, S., Mirabile, L. et al. Autologous Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (AHSCT): Standard of Care for Relapsing–Remitting Multiple Sclerosis Patients. Neurol Ther 9, 197–203 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-020-00200-9

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-020-00200-9