Abstract

This study was conducted to determine the influence of salinity on the growth of abalone Haliotis diversicolor Reeve, including the density and size of mucous cells. Abalone individuals were reared in the laboratory at salinities of 20, 25, 31, 35 and 40 ppt. The mucous cells of the lips, gills and digestive gut of H. diversicolor, which react to some forms of stress such as suboptimal salinity, were characterized following staining with Alcian Blue–Periodic Acid–Schiff`s Reagent (AB–PAS). The specific growth rate in wet weight and shell length of H. diversicolor were highest at 31 ppt and lowest at 20 ppt (0.52 vs 0.15% d−1, and 0.058 vs 0.021 mm d−1, respectively). The abalone H. diversicolor tolerated salinity fluctuations within the range of 20–40 ppt, but growth was optimum at 25–35 ppt. Mucous cells of the lips and gills showed significant differences (ANOVA, df = 4, P = <0.001) in cell density and cell size, being less dense and larger at 31 ppt than at 40 ppt, which could be an effect of osmotic and ionic regulation. Consistent with reports in literature, salinity ranges of 25–35 ppt are suitable for growth of H. diversicolor. Results of this study indicated that areas with such salinity are favorable for stock enhancement and mariculture of the abalone H. diversicolor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The abalone Haliotis diversicolor Reeve, 1846, commonly called ‘tokobushi’ in Japan, inhabit the rocky littoral to sublittoral zone (Geiger and Poppe 2000). In Tanegashima, Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan, H. diversicolor is an important fishery commodity with declining yield. Hence, the local government and fisheries cooperative associations are managing this fishery resource. Interventions include regulating the minimum size of harvest and releasing cultured juveniles in designated fishing grounds for stock enhancement (Alcantara and Noro 2005, 2006). In the Philippines, stock enhancement of abalone H. asinina resulted in spill-overs of abalone outside the release site (Salayo et al. 2016). On the other hand, the mariculture of abalone H. diversicolor involves hatchery, nursery and on-growing in inland facilities and grow-out in nearshore ponds and cages (Chen and Lee 1999; Creencia et al. 2016).

Fishers tend to gather larger individuals of H. diversicolor near estuaries (pers. obs.) which may be related to salinity. Salinity has some adverse effect on various aspects of the physiology of abalone. H. diversicolor at salinities lower or higher than optimum have reduced immunity and resistance to infection (Cheng et al. 2004), survival (Chen and Chen 2000) and growth (Chen et al. 2000). According to Chen et al. (2000), growth rate of H. diversicolor is optimum at 30–35 ppt with variable rates for different sizes of juveniles. We hypothesized that the seasonal inflow of freshwater in estuaries and the resulting decrease in marine salinity from 34–38 ppt to 31–33 ppt might have promoted faster growth of H. diversicolor (Chen et al. 2000). In general, faster growth of marine animals in intermediate salinities has been correlated with reduced metabolic rate and elevated assimilation efficiency (Boeuf and Payan 2001).

The lips, gills and digestive gut may react to changes in salinity level by adjusting the density and size of mucous cells and other epithelial cells. In varying salinities, epithelial mucous cells may adjust to local osmotic demands (Allen 1961; Gilles 1972; Yiyan et al. 2004; Di et al. 2012). Since mucous cells mainly contain water (Davies and Hawkins 1998), we hypothesized that the size and density of mucous cells in the lips, gills and digestive gut might reflect acclimation and adaptation to the prevalent water salinity. Acclimation to salinity in marine mollusks occurs via cellular mechanisms such as reversible changes of protein and RNA synthesis, alteration of molecular forms of enzymes, and regulation of ionic content and cell volume (Berger and Kharazova 1997). Various mucous cells are partly responsible for ionic regulation as well as lubrication of different organs (Crofts 1929; Davies and Hawkins 1998; Luchtel et al. 1997). However, there is limited information on the effect of acclimation to changes in salinity on mucous cell number and size.

Because of the regulatory activity of mucous cells, alteration of salinity may have effects on the overall physiology of abalone, as reflected in growth rate. Therefore, in this study we investigated the growth (wet weight and shell length) of abalone and their mucous cells (characterized by density and size) when reared at different salinities. The results will be useful for selecting sites for stock enhancement or mariculture and in designing inland culture systems for H. diversicolor. Abalone raised from the hatchery are released to fishing grounds to replenish the overfished wild population (Body 1987; Braje et al. 2007) and cultured to increase abalone products in the market (Troell et al. 2006, Wu and Zhang 2012).

Methods

One-year-old individuals of the abalone H. diversicolor produced from the hatchery facilities of Kagoshima Mariculture Society in Tarumizu City, Kagoshima, Japan, with total wet weight of 1.67 ± 0.49 g (mean ± SD) and shell length of 23.26 ± 1.90 mm, were used in this study. In the laboratory, the animals were maintained in 10-L plastic tanks with static seawater. Each tank was provided with a 7 × 7 × 6 cm3 portable filter-aerator and a shelter made from an inverted length of plastic guttering 15 × 5 cm2, with a central hole 6 cm in diameter. A shelter was necessary to provide a substrate for attachment and to cover the nocturnal abalone during daytime. Except for the control, salinity in each tank was gradually adjusted to the desired level within 1 week to acclimatize the test individuals. Dechlorinated tap water was added to decrease seawater salinity. Dissolved sea salt (Hagata, Japan sea salt) was added to increase salinity. The experiment began after an acclimation period of 2 weeks. Two replicate tanks for each of five treatments [salinity levels of 20, 25, 31(control), 35 and 40 ppt] were arranged in a completely randomized design. These salinities were chosen because they span the possible salinity ranges in coastal areas where H. diversicolor lives. The control was the salinity of the nearby sea where the seawater in the laboratory was pumped.

Ten individuals of H. diversicolor (2 tanks × 5 salinities) were maintained in each tank for 2 months. Rehydrated blades of kelp (Laminaria sp., from Kagoshima City local supermarket) were provided ad libitum and replaced every 3 or 4 days, simultaneous with change of the tank water. Water temperature, dissolved oxygen (DO) (YSI 85, YSI, USA) and pH (Yokogawa pH82, Japan) of the tank water in each tank were measured weekly. Values of percent DO saturation were computed using the DOTABLES on-line program (available at: water.usgs.gov). There was no management of bicarbonate levels during the experiment.

Growth was measured weekly by recording wet weight (WW) (electronic balance, Shimadzu EL-120 W/AC, Japan) and shell length (SL) (Vernier caliper, Mitotuyo Corp., Japan). The shells were blotted with paper towels before measuring the wet weight. Repeat weighing after re-immersion and blotting indicated an accuracy of ± 0.02 g. Specific growth rate was calculated as percentage increase in wet weight per day relative to original weight. This measure was used rather than absolute growth rate to reduce variability with size and age. On the other hand, to measure growth rate in shell length we used the absolute increase per day, because shell length is not affected as much by size or age.

The formulae used were:

Specific growth rate (% d−1) = (ln wetW2 − ln wetW1)/(d2 − d1) × 100

Growth rate in shell length (mm d−1) = (SL2 − SL1)/(d2 − d1)

where ln is the natural logarithm, wetW1 (g) is the wet weight of H. diversicolor at the start of the experiment, wetW2 (g) is the wet weight of H. diversicolor at the end of the experiment, SL1 (mm) is the initial shell length of H. diversicolor, SL2 (mm) is the final shell length of H. diversicolor, d1 is the initial day of the experimental culture period, and d2 is the final day of the experimental culture period.

At the end of the tank period, two individuals were randomly chosen from each tank for histological analyses. These individuals were relaxed in 5% ethanol then fixed in 10% seawater–formalin solution for 48–72 h and stored in 70% ethanol. About 1–2 cm of the lips, gills (lamellae) and digestive gut (stomach and intestine) from each individual were taken and dehydrated in a graded ethanol series (70, 80, 85, 90, 95, and 100%) with two changes at 10–12 h each. This was followed by gradual infiltration and embedding with the cold resin Glycol Methacrylate (GMA) (Technovit 7100®, HeraeusKulzer, Germany) at ethanol:GMA ratios of 4:1, 2:1, 1:1, 1:3, 0:1,0:1 for 10–12 h each. Sections of tissues that were 2 µm thin were stained with Alcian Blue–Periodic Acid–Schiff`s Reagent (AB–PAS) to test for the presence of mucopolysaccharides and glycoconjugates. The density (number per 0.01 mm2) and length (in µm) of mucous cells positive to AB–PAS (blue or purple to pink or magenta) in each organ were compared among the treatments. Using photomicrographs of ten different areas per individual sample, the number of teardrop-shaped mucous cells was counted and their corresponding maximum dimension of length was measured. The density and size (average of 20 cells) of mucous cells were measured using ImageJ (Image Processing and Analysis in Java). The ten areas per individual were blocked in the statistical analysis. An average density was calculated from 10 observations × 2 individuals × 5 salinities = 200 observations (40 per salinity treatment). For size, an average was calculated from 20 cells × 2 individuals × 2 tanks × 5 salinities = 400 observations (80 per salinity treatment).

To determine if the differences in the growth rates of H. diversicolor, and the density and size of mucous cells positive to AB–PAS among the salinity treatments were significant, single-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by pairwise multiple comparisons (Tukey Test) was performed using SIGMASTAT (Systat Software Inc., California, USA).

Results

Environmental conditions

The average measured salinity was usually a little higher than the nominal salinity (Table 1). Average DO in tanks ranged from 6.13 to 6.76 mg L−1, the average DO saturation ranged from 84.96 to 86.48%, and the average pH values ranged from 7.65 to 7.79. There were no significant differences (ANOVA, P > 0.05) between the two tanks in each treatment for salinity, DO or pH. Indoor water temperature during the experimental period decreased from 24.2 °C (October) to 12.4 °C (December) as the ambient temperature decreased with the progress of winter, which was similar to what would be experienced by abalone in their natural marine habitat. The temperature was the same in all treatments and did not affect the readings of salinity, DO or pH for the duration of the experiment. Survival rate of abalone was 100% in all treatments for the duration of the experiment.

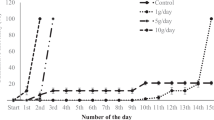

Growth rate

There were significant differences in specific growth rate of abalone H. diversicolor among the salinity treatments (ANOVA, df = 4, P = <0.001). The specific growth rate was highest at 31 and lowest at 4 and 20 ppt (Table 2). Moreover, there were significant differences in SL growth rate of abalone among the salinity treatments (ANOVA, df = 4, P = <0.001). The highest SL growth rate was obtained at 31 ppt and lowest at 40 and 20 ppt (Table 2).

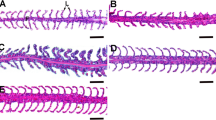

Density of mucous cells

There were significant differences in the density of AB–PAS-positive mucous cells (Fig. 1) of the lips of abalone among treatments (ANOVA, df = 4, P = <0.001). The density of mucous cells from the lips of abalone reared at 40 ppt was significantly higher (P = 0.03) than in those raised at 31 ppt (Table 3). In the gills, there were significant differences in the density of AB–PAS-positive mucous cells (Fig. 2) of abalone among treatments (ANOVA, df = 4, P = <0.001). The density of mucous cells from gills of abalone reared at 40 and 35 ppt was significantly higher (P = <0.001) than cell densities of abalone raised at 20, 25 and 31 ppt (Table 3). In the digestive gut, there were significant differences in density of AB–PAS-positive mucous cells (Fig. 3) of abalone among treatments (ANOVA, df = 4, P = <0.001). Density of mucous cells from digestive gut of abalone reared at 25 ppt (19.0 ± 1.9 cells per 0.1 mm2) were significantly higher (P = 0.04) than those reared at 20 ppt (Table 3).

Photomicrograph of the gill of H. diversicolor stained with H–E: a longitudinal section of gill filaments showing the afferent end (A) and efferent end (E), scale bar = 100 µm; b enlarged efferent end showing mucous-1 (M1), mucous-2 (M2) and cilia (Ci), hemocoelic space (HS) and nerve (N), bar = 10 µm

Sizes of mucous cells

There were significant differences in sizes of AB–PAS-positive mucous cells from the lips of abalone among treatments (ANOVA, df = 4, P = 0.021). The lengths of the mucous cells of lips of abalone raised at 31 ppt were significantly greater than those from abalone reared at 40 ppt (Table 4). In the gills, there were significant differences in sizes of AB–PAS-positive mucous cells among treatments (ANOVA, df = 4, P = <0.001). The mucous cells of gills of individuals reared at 31 ppt were significantly longer than those reared at 40 ppt (Table 4). In the digestive gut, there were significant differences in sizes of AB–PAS-positive mucous cells among treatments (ANOVA, df = 4, P = <0.001). The AB–PAS-positive mucous cells from abalone raised at 20 ppt were significantly longer than those from abalone raised at 35, 31 and 25 ppt (Table 4).

Discussion

Growth

Salinity in coastal areas where the abalone H. diversicolor lives may drop sharply during heavy rains and large discharge events from rivers and streams. Alternatively, salinity may rise in tide pools during low tides with high rates of evaporation. The normal range of salinity in H. diversicolor habitat is 32 ± 3 ppt. The 100% survival in five different salinity levels tested indicates that the range of 20–40 ppt is tolerated by H. diversicolor in culture. This is an important finding and supports the occurrence of H. diversicolor in some estuarine areas where our results show a wider range than the 25–35 ppt marine water range suitable for the growth of H. diversicolor reported by Chen and Chen (2000). In the earlier farming studies of H. diversicolor in Taiwan, the reported salinity range is 30–35 ppt (Chen 1984). There is a wide range of salinity tolerance across the genus Haliotis in general. The salinity tolerance of Haliotis laevigata Leach and Haliotis rubra Leach is from 25 to 40 ppt and mortality occurs at 2 ppt outside this range (Edwards 2003). Individuals of Haliotis asinina Linnaeus survive at lower salinity levels, 20.5 ppt without acclimation and down to 12.5 ppt with gradual acclimation, but die at 10 ppt (Singhagraiwan et al. 1992).

During the conduct of this experiment, water temperature was decreasing due to the onset of winter (October–December) in the study site. Temperature was not considered to affect the growth of the abalone H. diversicolor reared at five different salinities because they would experience such water temperatures in their natural habitat. Generally, the effect of temperature on growth of various abalone species would depend on what temperature range they are exposed to in their natural environment. For instance, in California the abalone Haliotis rufescens Swainson that inhabits deep cool water has been reported to decrease growth at increasing temperature, whereas the abalone Haliotis fulgens Philippi that inhabits warm water has increased growth at higher temperature (Vilchis et al. 2005). On the other hand, in Chile the abalones Haliotis discus hannai Ino and H. rufescens cultured in tank systems have low growth during austral winter and high growth during the austral summer Mardones et al. (2013).

As indicated by both the growth rates in wet weight and shell length, 31 ppt is the most favorable salinity for H. diversicolor reared in culture, closely followed by 35 and 25 ppt. This implies that a salinity fluctuation of ± 4–6 ppt from 31 ppt is still favorable for growth of H. diversicolor in the wild or in a culture facility. Our results indicate a wider optimum salinity range than that of Chen (1984) and Chen et al. (2000) who reported that the optimum salinity for the growth of H. diversicolor is from 30 to 35 ppt. In our study, we used Laminaria as food, whereas Chen et al. (2000) gave formulated diet. Moreover, we have related the effect of salinity to mucous cells which might have influenced the growth performance of abalone. Since mucous cells principally contain water (Davies and Hawkins 1998), these cells are responsible for volume regulation of mucous in the body to better adapt to salinity stress (Drew et al. 2001); hence, the changes in density and size of mucous cells directly affect the growth of abalone. In another study, individuals of H. diversicolor of a similar age raised in similar tanks, densities, and temperatures but at slightly higher salinity (32–34 ppt) have a specific growth rate of 0.44% d−1, (Alcantara and Noro 2006), similar to that of abalone in this study raised at 35 ppt but lower than those raised at 31 ppt. The optimal range of salinity across marine mollusks having similar natural habitats generally appears to be similar. For example, the scallop Argopecten purpuratus Lamarck, the pearl-oyster Pinctada maxima Jameson and the clam Laternula marilina Reeve show the highest growth between 27 and 30 ppt (Navarro and Gonzalez 1998; Taylor et al. 2004; Zhuang 2005). However, there are often differences among local habitats of other mollusks in general and among abalone in particular. The higher growth rate exhibited at 40 ppt compared to 20 ppt (for weight) and at 35 ppt over 25 ppt (for shell length) may suggest that individuals of H. diversicolor can better adapt to higher salinity. On the contrary, individuals of H. laevigata and H. rubra can adapt better at lower rather than higher salinity within the range of 25–40 ppt (Edwards 2003).

Although abalone are exclusively marine species, results of previous studies (i.e. Singhagraiwan et al. 1992; Edwards 2003) and this study reveal that their growth performance is enhanced at intermediate salinity. The control treatment seawater (31 ppt) was sampled near (~ 800 m) a river mouth and thus was slightly diluted by river influx. Several studies have speculated on the physiological advantages of lower salinity on growth. Greater growth of some mollusks at lower salinities is due to the lower energetic cost of ionic and osmotic regulation, high food intake, efficient food conversion ratio, high retention of nutrients, low excretion of metabolites and low oxygen consumption (Ghiretti 1966). On the other hand, at higher salinities abalone spends more energy in counteracting stress rather than investing in growth, thus resulting in reduced growth rate (Morash and Alter 2016). It has been implicated that during seasonal salinity fluctuations the chemical balance between the environment and the body fluids is disrupted and efforts to regain homeostatic balance is an energetically costly process for abalone (Martello et al. 1998; Morash and Alter 2016). Further, suboptimal low salinity causes added stress to the abalone Haliotis varia Linnaeus when exposed to toxic substances (Lasut 1999). As in other marine mollusks, cell volume is regulated during variation in external salinity using intracellular free amino acids as osmotic solutes (Baginski and Pierce 1975; Amende and Pierce 1980) causing changes in water content and weight of abalone (Morash and Alter 2016). In our study, the lowest salinity (20 ppt) is the least favorable to the growth of H. diversicolor. This can be explained by their adaptive capacity at this particular salinity (Javanshir 2013) which affects their feeding behavior, metabolism and growth (Riisgard et al. 2012). Favorable feeding behavior, metabolism and growth of H. diversicolor aqualitis, a subspecies of H. diversicolor, all benefit at 25–37 ppt (Yan et al. 2009).

Mucous cells

The lips, gills and digestive gut of abalone are some of the organs that may show pronounced reactions to different salinity levels. The lip is directly exposed to the environment and contains many mucous and sensory cells. Changes in the cells of the lip may affect the abalone’s ability to graze and ingest. Salinity directly influences feeding of mollusks (Broom 1985; Riisgard et al. 2012). According to Chen et al. (2000), H. diversicolor feeds on artificial diets at salinity range of 20–38 ppt which means that they feed on a wide salinity range. In another study, the gastropod Lithopoma tectum has increased ingestion of algae after exposure to reduced-salinity water (Irlandi et al. 1997). In the case of abalone, highest growth of those reared at 31 ppt could be due to high intake of algal food compared to those at 40 and 20 ppt.

The bipectinate gills are positioned under the shell openings and are thus directly exposed to the salinity of the environment because the water passes through them. This organ is very sensitive because each filament is innervated and contains several mucous and ciliated epithelial cells (Wanichanon et al. 2004). In the gills, mucous cells are important in detecting salinity stress. According to Drew et al. (2001), the abalone Haliotis rubra Leach are able to regulate the swelling of tissues due to exposure to hyposaline stress. Thus, salinity stress are able to affect the growth of abalone by diverting energy usage to addressing the stressful condition. In this study, salinity stress caused by prolonged exposure to hypersaline (40 ppt) culture environment results in higher density and smaller sizes of mucous cells in externally located lips and gills but not in internally located digestive gut. The digestive gut is located internally, hence its function is not influenced by salinity. However, mucous cells in the digestive system may produce hormones such as hydrolases that are active in osmoregulation, control of food intake and growth regulation (Gilles 1972; Harris et al. 1998; Di et al. 2012).

Implications on stock enhancement and mariculture

Results of this study has application in choosing areas with average salinity of 31 ± 4 ppt for stock enhancement and open sea culture system of abalone H. diversicolor. To ensure favorable survival and growth of abalone released or reared in the site, one of the important considerations is the potential seasonal fluctuation of salinity due to rainy or dry season and other factors that may cause drastic change in water salinity. For land-based mariculture system of abalone, the findings will be helpful in designing and developing mariculture facilities and protocols that will minimize salinity stress and other forms of stress to optimize production and produce high-quality abalone product.

Conclusions

Generally, the growth (wet weight and shell length) of H. diversicolor was greatest at 31 ppt and lowest at 40 and 20 ppt with those at 35 and 25 ppt having average growth performance. Mucous cells positive to AB–PAS of lips and gills had their highest density and smallest cell size at 40 ppt and lowest density and largest cell size at 31 ppt. These findings suggest that differences in density and size of mucous cells could be an effect of osmotic and ionic regulation of H. diversicolor. It appears that mucous cells proliferate at the least favorable salinity level (40 ppt) compared with the salinity level suitable for growth (31 ppt). In non-optimal salinities, a high level of mucous cell production may be needed to maintain the ionic concentration of the blood in the anisosmotic extracellular regulation of some mollusks (Florkin 1966), which may also happen in H. diversicolor.

Change history

29 June 2018

The original version of this article unfortunately contained a mistake.

References

Alcantara L, Noro T (2005) Effects of macroalgal type and water temperature on macroalgal consumption rates of the abalone Haliotis diversicolor Reeve. J Shellfish Res 24:1169–1177

Alcantara L, Noro T (2006) Growth of the abalone Haliotis diversicolor (Reeve) fed with macroalgae in floating net cage and plastic tank. Aquac Res 37:708–717

Allen K (1961) The effect of salinity on the amino acid concentration in Pangia cuneata (Pelecypoda). Biol Bull 121(3):419–424

Amende LM, Pierce SK (1980) Cellular volume regulation in salinity stressed mollusks: the response of Noetia ponderosa (Arcidae) red blood cells to osmotic variation. J Comp Physiol 138:283–289

Baginski RM, Pierce SK (1975) Anaerobiosis: a possible source of osmotic solute for high-salinity acclimation in marine mollusks. J Exp Biol 62:589–598

Berger VJ, Kharazova AD (1997) Mechanisms of salinity adaptations in marine mollusks. In: Naumov AD, Hummel H, Sukhotin AA, Ryland JS (eds) Interactions and adaptation strategies of marine organisms. Hydrobiologia, vol 355. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Belgium, pp 115–126

Body AGC (1987) Abalone culture in Japan. Mar Fish Rev 49(4):75–76

Boeuf G, Payan P (2001) How should salinity influence fish growth? Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol 130(4):411–423

Braje TJ, Erlandson JM, Rick TC (2007) An historic Chinese abalone fishery in California’s Northern Channel Islands. Hist Archaeol 41(4):117–128

Broom MJ (1985) ICLARM studies and reviews. The biology and culture of marine bivalve mollusks of the Genus Anadara. International Center for Living Aquatic Resources Management, Manila

Chen HC (1984) Recent innovations in cultivation of edible mollusks in Taiwan with special reference to the small abalone Haliotis diversicolor and the hard clam Meretrix lusoria. Aquaculture 39:11–27

Chen JC, Chen WC (2000) Salinity tolerance of Haliotis diversicolor supertexta at different salinity and temperature levels. Aquaculture 181:191–203

Chen JC, Lee WC (1999) Growth of Taiwan abalone Haliotis diversicolor supertexta fed on Gracilaria tenuistipitata and artificial diet in a multiple-tier basket system. J Shellfish Res 18:627–635

Chen C, Zhong Y, Wu Y, Cai H, Guo C, Zheng L (2000) The effect of salinity on food intake, growth and survival of Haliotis diversicolor supertexta. J Fish China 24:41–45 (in Chinese with English abstract)

Cheng W, Juang F-M, Chen J-C (2004) The immune response of Taiwan abalone Haliotis diversicolor supertexta and its susceptibility to Vibrio parahaemolyticus at different salinity levels. Fish Shellfish Immunol 16:295–306

Creencia LA, Noro T, Fukumoto M (2016) Composition, size and relative density of diatoms in the stomach of 4–75 day-old juvenile abalone Haliotis diversicolor (Reeve). Palawan Sci 8:1–12

Crofts DR (1929) Liverpool marine biology committee. Haliotis. The University Press of Liverpool, UK

Davies MS, Hawkins J (1998) Mucus from marine molluscs. Adv Mar Biol 34:1–71

Di G, Ni J, Zhang Z, Yon W, Wang B, Ke C (2012) Types and distribution of mucous cells of the abalone Haliotis diversicolor. Afr J Biotechnol 11(37):9127–9140

Drew B, Miller D, Toop T, Hanna P (2001) Identification of expressed HSP’s in blacklip abalone (Haliotis rubra Leach) during heat and salinity stress. J Shellfish Res 20(2):695–703

Edwards S (2003) Assessment of the physiological effect of altered salinity on greenlip (Haliotis laevigata) and blacklip (Haliotis rubra) abalone using respirometry. Aquac Res 34:1361–1365

Florkin M (1966) Nitrogen metabolism. In: Wilbur KU, Yonge CM (eds) Physiology of mollusca, vol II. Academic Press, New York, pp 309–351

Geiger D, Poppe G (2000) The family haliotidae, A conchological iconography. Conch Books, Hackenheim, p 135

Ghiretti F (1966) Respiration. In: Wilbur KU, Yonge CM (eds) Physiology of mollusca, vol II. Academic Press, New York, pp 175–208

Gilles R (1972) Osmoregulation in three molluscs: acanthochitona discrepans (Brown), Glycymeris glycymeris (L.). and Mytilus edulis (L.). Biol Bull 142:25–35

Harris JO, Burke CM, Maguire GB (1998) Characterization of the digestive tract of greenlip abalone, Haliotis laevigata Donovan. I. Morphology and histology. J Shellfish Res 17(4):979–988

Irlandi E, Macia S, Seraf J (1997) Salinity reduction from freshwater canal discharge: effects on mortality and feeding of an urchin (Lytechinus variegatus) and a gastropod (Lithopoma tectum). Bull Mar Sci 61(3):869–879

Javanshir A (2013) Low salinity changes in an intertidal zone may affect population dynamics of Littorina scabra (Linaeus 1758) in northern coasts of Persian gulf. Turkish J Fish Aquat Sci 13(1):133–138

Lasut MT (1999) Effects of salinity-cyanide interaction on the mortality of abalone Haliotis varia (Haliotidae: Gastropoda). In: Proceedings of the 9th workshop of the tropical marine molluscprogramme (TMMP), Phuket Marine Biological Center, Indonesia, 19–29 August 1998. Part 1. Special publication, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 165–168

Luchtel DL, Martin AW, Deyrup-Olsen I, Boer HH (1997) Gastropoda: pulmonata. In: Harrison FW, Kohn AJ (eds) Microscopic anatomy of invertebrates mollusca. Wiley-Liss, New York

Mardones A, Augsburger A, Vega R, de Los Rios-Escalante P (2013) Growth rates of Haliotis rufescens and Haliotis discus hannai in tank culture systems in southern Chile (41.5 °C). Lat Am J Aquat Res 41(5):959–967

Martello LB, Tjeerdemab RS, Smithc WS, Kautenc RJ, Crosbyd DG (1998) Influence of salinity on the actions of pentachlorophenol in Haliotis as measured by in vivo 31P NMR spectroscopy. Aquat Toxicol 41(3):229–250

Morash AJ, Alter K (2016) Effects of environmental and farm stress on abalone physiology: perspectives for abalone aquaculture in the face of global climate change. Rev Aquac 8:342–368

Navarro JM, Gonzalez CM (1998) Physiological responses of the Chilean scallop Argopecten purpuratus to decreasing salinities. Aquaculture 167:315–327

Riisgard HM, Battiger L, Pleissoner D (2012) Effect of salinity on growth of mussels, Mytilus edulis, with special reference to Great Belt (Denmark). Open J Mar Sci 2:167–176

Salayo ND, Castel RJG, Barrido RT, Tormon DHM, Azuma T (2016) Community-based stock enhancement of abalone, Haliotis asinina in Sagay marine reserve: achievements, limitations and directions. In: Hajime K, Iwata T, Theparoonrat Y, Manajit N, Sulit VT. Consolidating the strategies for fishery resources enhancement in southeast Asia. Proceedings of the symposium on strategy for fisheries resources enhancement in the southeast Asian Region, Pattaya, Thailand, 27–30 July 2015. pp 131–135

Singhagraiwan T, Doi M, Sasaki M (1992) Salinity tolerance of juvenile Donkey`s ear abalone, Haliotis asinina Linne. Thailand Mar Fish Res Bull 3:71–77

Taylor JJ, Southgate PC, Rose RA (2004) Effects of salinity on growth and survival of silver-lip pearl oyster, Pinctada maxima, spat. J Shellfish Res 23:375–377

Troell M, Robertson-Anderson D, Anderson R, Bolton JJ, Maneveldt G, Halling C, Probyn T (2006) Abalone farming in South Africa: an overview in perspectives in kelp resources, abalone feed, potential for on-farm seaweed production and socio-economic importance. Aquaculture 257:266–281

Vilchis LI, Tegner MJ, Moore JD, Friedman CS, Riser KL, Robbins TT, Dayton PK (2005) Ocean warming effects on growth, reproduction and survivorship of southern California abalone. Ecol Appl 15(2):469–480

Wanichanon C, Laimek P, Linthong V, Sretarugsa P, Kruatrachue M, Upatham ES, Poomtong T, Sobhon P (2004) Histology of hypobranchial gland and gill of Haliotis asinina Linnaeus. J Shellfish Res 23:1107–1112

Wu F, Zhang G (2012) Suitability of cage culture for Pacific abalone Haliotis discus hannai Ino production in China. Aquac Res 44:485–494

Yan XZ, Wang GZ, Li SJ (2009) Effects of water salinity on energy budget of Haliotis diversicolor aquatilis. Chin J Ecol 28(8):1520–1524

Yiyan W, Hushan S, Meiyu Z (2004) Types and distribution of mucous cells in the digestive tract in abalone Haliotis discus hannai Ino. Fish Sci 23(5):1–4

Zhuang S (2005) Influence of salinity, diurnal rhythm and daylength on feeding in Laternula marilina Reeve. Aquac Res 36:130–136

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Kyushu Electric Company for research funds and Kagoshima Mariculture Society in Tarumizu City, Kagoshima, Japan, for individuals of Haliotis diversicolor. We are also grateful for the inputs of peers that improved the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Creencia, L.A., Noro, T. Effects of salinity on the growth and mucous cells of the abalone Haliotis diversicolor Reeve, 1846. Int Aquat Res 10, 179–189 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40071-018-0199-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40071-018-0199-0